Abstract

Background

Depression, a major outcome in cancer patients, is often evaluated by physicians relying on their clinical impressions rather than patient self-report. Our aim was to assess agreement between patient self-reported depression, oncologist assessment (OA), and psychiatric clinical interview (PCI) in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer (AOC).

Methods

This analysis was a secondary endpoint of the Elderly Women AOC Trial 3 (EWOT3), designed to assess the impact of geriatric covariates, notably depression, on survival in patients older than 70 years of age. Depression was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale-30 (GDS), the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, the distress thermometer, the mood thermometer, and OA. The interview guide for PCI was constructed from three validated scales: the GDS, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, revised (DSM) criteria for depression were used as a gold standard.

Results

Out of 109 patients enrolled at 21 centers, 99 (91%) completed all the assessments. Patient characteristics were: mean age 78, performance status ≥2: 47 (47%). Thirty six patients (36%) were identified as depressed by the PCI versus 15 (15%) identified by DSM. We found moderate agreement for depression identification between DSM and GDS (κ=0.508) and PCI (κ=0.431) and high agreement with MADRS (κ=0.663). We found low or no agreement between DSM with the other assessment strategies, including OA (κ=−0.043). Identification according to OA (yes/no) resulted in a false-negative rate of 87%. As a screening tool, GDS had the best sensitivity and specificity (94% and 80%, respectively).

Conclusion

The use of validated tools, such as GDS, and collaboration between psychologists and oncologists are warranted to better identify emotional disorders in elderly women with AOC.

Introduction

Depression is a major outcome in cancer patients, with an estimated frequency of 16%,Citation1 and this frequency is reported to be higher for elderly patients (45%).Citation2 Depression is the most common psychiatric illness in patients with cancer and it is known to reduce patients’ quality of life and to decrease their adherence to medical treatments.Citation3–Citation5 Depressive symptoms (asthenia, sleep disturbances, anorexia, etc) have been reported to significantly affect patients and their families.Citation3,Citation6 Moreover, recent studies have shown that depression is an independent predictive factor for cancer-related mortality,Citation7–Citation9 even though depression usually responds well to treatment (nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic).Citation10–Citation12

The evaluation of depression has been a challenge because symptoms cover a broad spectrum, from sadness to major depressive disorder, and because mood change is often difficult to assess when patients are confronted by repeated threats to life or are experiencing pain.Citation6

For a depression diagnosis, clinicians typically rely on their clinical impression rather than on patient self-report or structured assessment.Citation13,Citation14 A systematic routine screening for depression has been implemented in some cancer care settings. Nevertheless, a substantial amount of data shows that depression remains underdiagnosed and undertreated in older patients, especially in the context of cancer,Citation15–Citation19 with low agreement between physicians and patients about the prevalence of mild and moderate/severe depression (33% and 13%, respectively).Citation20–Citation22 Similar results have been reported for nurses.Citation14,Citation23 Several reasons have been highlighted to explain those barriers to diagnosis and thus to adequate treatment.

First, many cancer patients are not treated for depression due to assessment difficulties, especially with older patients.Citation6,Citation19 This population often develops symptoms that differ from those experienced by younger patients, with more somatic complaints and fewer emotional symptoms (sadness, guilt, anhedonia).Citation18,Citation19 Patients in later adulthood are more reluctant to report depressive symptoms such as sadness or suicidal ideations.Citation12 Furthermore, they might consider these symptoms as belonging to aging processes.Citation12

Those difficulties may be due to nondisclosure by the patients themselves, who may feel they are wasting the doctor’s time or that they are in some way to blame for their distress and therefore choose to hide their feelings.Citation24 There is also the wrong belief among some professionals that terminal illness invariably causes depression,Citation25 and there are disagreements about the meaning of the term “depression” within psychiatric classification.Citation26 We also know that some symptoms of depression (eg, fatigue, loss of appetite) might be expected consequences of physical illness.Citation27,Citation28 It is possible that some of the difficulties faced when attempting to identify depression might be decreased by the use of appropriate screening scales (adapted to the population and to the clinical setting).Citation12

This study aimed to assess agreement between patient self-reported depression using different scales,Citation18 oncologist assessment (OA) based on the oncologist’s clinical impressions, and a psychiatric clinical interview (PCI) conducted by a psychologist using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, revised (DSM)Citation29 among elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer (AOC).

Methods

This analysis was a secondary endpoint of the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO) Elderly Women AOC Trial 3 (EWOT3) Phase II multicenter trial, designed to assess the impact of geriatric covariates, notably depression, on survival in patients older than 70 years of age receiving six courses of carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for stage 3–4 ovarian cancer. The local ethics committee and the Institutional Review Board at the Hospices Civils de Lyon approved this study, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Participants

To be included, patients had to have advanced (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage 3 or 4) ovarian cancer and be older than 70 years of age. They could not have received chemotherapy previously and should have had a life expectancy of at least 3 months. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and patient characteristics have been previously reported.Citation30

Assessments

Emotional disorders – and particularly depression – were assessed using patient self-report, OA, and PCI. Chronologically, oncologists were asked to provide their clinical impression before the self-reports. The PCI was performed within 10 days of enrollment according to the trial design, and the interviewer was blinded to the OA and to the self-report results.

Self-reports

All self-reports used were validated in their French form and included the Geriatric Depression Scale-30 (GDS),Citation31 the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS),Citation32,Citation33 the distress thermometer (DT), and the mood thermometer (MT).Citation34 The GDS is a 30-item scale. This scale has been developed and validated especially for depression screening among elderly patientsCitation35,Citation36 and has also been used in cancer patients.Citation37 Scores of 0–9 are considered normal, 10–19 indicate mild depression, and 20–30 indicate severe depression.Citation35 The HADS is a 14-item scale with separate subscales for anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). It has been validated in cancer patients for depression and anxiety diagnosisCitation38 and can be administered or used as a self-assessment tool. The DT is a one-item self-report screening tool for assessing psychological distress in cancer patients.Citation39 The DT asks patients to rate the intensity of their psychological distress using an eleven-point visual analog scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress),Citation40 with a score of 4 used to indicate a significant level of distress.Citation41 The MT is a one-item self-report screening tool for measuring mood in cancer patients.Citation34 Patients are asked to answer the question “How depressed have you been today and over the last week?” by rating their answer on a 0–10 scale (0 = normal mood; 10 = extreme depression). A score of 4 is used to indicate a significant level of depression.Citation34 All of these self-report assessment tools were transformed into binary variables with the following cutoff scores : ≥10/30 for GDS-30, >14/42 for HADS, >4/10 for MT, and >4/10 for DT.

Oncologist assessment

Oncologists were invited to give their clinical impression regarding depression (yes/no). This item was previously shown to be correlated to survival in two previous GINECO studies of elderly patients with AOC.Citation42

Psychiatric clinical interview

A PCI was conducted by psychologists within 10 days of enrollment. The interview guide for the PCI was constructed and adapted from the DSM criteria and three validated scales: GDS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), according to a structured interview guide for evaluating depression in elderly patients developed by Tison.Citation43 Psychologists were to assess depression using DSM criteria (DSM major depressive disorder, yes/no) and to give their clinical impression (PCI, yes/no). The DSM was considered to be the gold standard.Citation18

Procedure and outcomes

Demographic information (ie, age) and clinical data (ie, performance status, albumin level, weight, cancer diagnosis, and metastatic status) were collected.

Patient functioning was assessed using two validated tools: basal Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL).Citation44–Citation47

On the day of enrollment, patient assessments included a clinical evaluation, laboratory results, and psychological self-reports (HADS, DT, MT, and GDS-30). In the 10 days after enrollment, a PCI based on MADRS and HDRS questionnaires was conducted.

Survival data were collected from the medical chart, starting from the time of enrollment to the patient’s death. Patients alive at the time of data collection were included in the analysis as censored cases using the date of last follow-up.

Statistical considerations

The number of patients to include was defined in the first aim of the GINECO EWOT3 study, a secondary endpoint of which is examined in the current study, using previous findings from our group.Citation42 A single analysis requires a sample of 105 patients, assuming that depression triples the risk of death (two-tailed test), with a significance level of α=5% and a power of 90% (β=10%).Citation30 This calculation was based on the assumption, on the basis of results from the EWOT1 and EWOT2 studies, that a death rate of 85% is expected at 2 years (86.4%, according to EWOT1 and EWOT2).

Categorical variables were presented by their frequencies and percentages and continuous variables by their means and standard deviations if they were normally distributed. When not normally distributed, data were reported by their median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3) and analyzed using nonparametric methods. Mann–Whitney U-tests and chi-square tests were performed to determine factors associated with depression according to the DSM. Agreements between depression diagnosis and DSM, PCI, and self-reported assessments were evaluated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ).

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

One hundred and nine patients had a psychological assessment; of these, 99 had a complete set of psychological data and were included in the analysis. Patients’ characteristics are presented in .

Table 1 Patient characteristics, N=99

Depression assessments

Out of the 99 patients included, 15 (15%) were depressed according to DSM and 39 (39%) were depressed according to PCI. We found different levels of agreement between DSM – considered as the gold standard – and other assessments ():

no agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.0 and 0.2): with the DT (κ=−0.060), MT (κ=0.058), HADS (κ=0.127), HDRS (κ=0.151), and OA (κ=−0.043)

moderate agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.4 and 0.6): with GDS (κ=0.508) and with PCI (κ=0.431)

high agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.6 and 0.8): with MADRS (κ=0.663).

Table 2 Comparison of depression diagnosis using different strategies between depressed and nondepressed patients according to DSM diagnosis, N=99

Considering the agreement between CPI and other assessments, results are the following:

no agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.0 and 0.2): with the DT (κ=−0.060), MT (κ=0.193), HADS (κ=−0.051), and OA (κ=−0.061),

low agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.2 and 0.4): with HDRS (κ=0.389),

moderate agreement (kappa coefficient between 0.4 and 0.6): with DSM (κ=0.431), with GDS (κ=0.517), and with MADRS (κ=0.494).

The tool giving the best combination of sensitivity/specificity for depression screening among elderly patients was the GDS (cutoff score ≥10), with a sensitivity of 0.94 and a specificity of 0.80 as compared to DSM (). The DT, MT, and HADS had very poor sensitivity/specificity for depression identification (0.50/0.40, 0.50/0.57, and 0.50/0.67, respectively). Among clinical assessments, a good sensitivity/specificity (1.00/0.71) was obtained with the PCI, whereas OA resulted in a very low sensitivity (0.13).

Table 3 Sensitivity and specificity of the different assessments to DSM

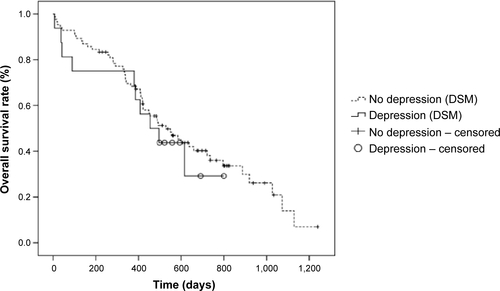

Depression and overall survival

Mean survival was 15.7 months (standard deviation = 9.2 months). We did not find any significant difference regarding patients’ characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients according to DSM (). Patients with major depressive disorder according to the DSM tended to have a shorter overall survival than did nondepressed patients, at 14.9 months (3.0–18.3 months) versus 15.2 months (9.4–22.8 months); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.281).

Table 4 Associations between depression diagnosis according to DSM and patient characteristics, N=99

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to assess the level of agreement between patient self-reported depression rated on different scales, oncologist clinical impression, and a PCI conducted by a psychologist using the DSM criteria among elderly patients with AOC. We found moderate agreement for depression identification between DSM and GDS (κ=0.508) and PCI (κ=0.431) and high agreement with MADRS (κ=0.663). We found low or no agreement between DSM and the other assessments strategies, including OA (κ=−0.043). One explanation may be the difficulty, according to the DSM classification, to connect somatic symptoms with depression, considering that ovarian cancer may lead to appetite change, fatigue, and libido or sleep disruption.

This result confirms the importance of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and the work of Jacobsen regarding the implementation of systematic strategies for distress screening among cancer patients.Citation48–Citation50 Indeed, OA results in a false-negative rate of more than 80%, leading to the recommendation that health care professionals without specific training for depression diagnosis should be encouraged to use validated tools in their daily clinical practice.

The screening tool with the best combination of sensitivity/specificity for depression among elderly patients with AOC was the GDS, with a sensitivity of 0.94 and a specificity of 0.80. These results suggest that the GDS is a good tool, as part of a screening “routine” among elderly patients with AOC, and should be preferred to more classic and unspecific tools such as the DT or the HADS. Our results might be partially explained by the fact that most of the scales for depression screening/diagnosis were validated among middle-aged patients.Citation51

The systematic use of this type of tool (eg, GDS) has been widely advocated to improve the identification of depression in this frail population.Citation2,Citation20,Citation52 However, the vast majority of cancer centers do not have a strategy for the identification of depression in patients with late-stage cancer. Our results suggest that some existing tools are consistent with the DSM diagnosis of depression that is still considered as the gold standard. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that we should distinguish first-line tools (screening) from second-line tools (diagnostic).Citation11,Citation26,Citation50,Citation53 Indeed, even if these tools allow easy identification of depression, in case of treatment failure and/or severe risk factors, these patients should be referred to a mental health specialist to confirm the diagnosis.Citation54

Our group has recently published a report proposing a geriatric vulnerability score in elderly patients with AOC.Citation30 In this previous work, we used the HADS for the development of the vulnerability score. Our findings suggest that this score is less accurate than the GDS for the identification of depression. More research is necessary on the best way to screen for depression among this specific population, so as to allow simple screening in daily practice. It is important to recognize that in this population of patients with severe physical and/or psychosocial distress, only very brief assessments are likely to be adopted in clinical practice.

We did not find significant difference in overall survival between depressed patients and nondepressed patients (, ). These results are in contradiction with our previous results, which reported a significant impact of OA and HADS on survival.Citation42,Citation55 These results were recently confirmed in a pooled analysis of EWOT1, EWOT2, and EWOT3 (submitted) data, leading to the idea that emotional disorders in general, including cancer distress, might have a more significant impact on survival than authentic depression as defined by DSM. Such results are in line with the current debate on HADS performance, considered as poor in depression identificationCitation56,Citation57 but powerful in predicting various medical outcomes.Citation58 More research is necessary to better characterize the association between both depression and survival among elderly cancer patients.

The main limitation of this study was that this analysis was a secondary endpoint of the GINECO EWOT3 Phase II multicenter trial, designed to assess the impact of geriatric covariates, notably depression, on survival in elderly patients with AOC. As a result, the sample size was not calculated regarding sensitivity and specificity of the different tools as compared to DSM, limiting generalization of our results.

Another limitation is that all the threshold scores used for this study come from existing literature and it is known that sensitivity and specificity of the instrument depends on cutoff points, which might need to be changed in different patient populations (eg, inpatients, outpatients, and elderly patients, or by stage and type of disease).Citation59 This is probably true for all these tools, and future research should try to explore this issues using the same tool among different populations. Finally, our results suggest that depression systematic screening using specific tool (eg, GDS) is feasible and efficient, and that these tools should be selected according to the population and the clinical setting. More research is also necessary to better understand what should be done in case of positive screening for depression. Research that includes prospective longitudinal studies will help to characterize depression and develop optimal treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Douglas Micheau-Bonnier, Nicolas Gane, and Bénédicte Votan from the GINECO study office, the Délégation à la Recherche Clinique et à l’Innovation of the Hospices Civils de Lyon and Raymonde Maraval-Gaget. We also thank the following investigators and psychologists who participated in the trial: Drs B Weber, MC Kaminsky, and E Luporsi (Centre Alexis Vautrin-Brabois, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy), Prof H Curé, Drs AM Savoye and G Yazbek (Institut Jean Godinot, Reims), Drs I Ray-Coquard, JP Guastalla, and O Tredan (Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon), Dr E Sevin (Centre François Baclesse, Caen), Drs L Stefani and J Provençal (Centre Hospitalier de la région d’Annecy, Pringy), Drs S Kalla, F Savinelli, and G Deplanque (Groupe Hospitalier Saint-Joseph, Paris), Drs M Combe and M Atlassi (Centre Hospitalier du Mans, Le Mans), Dr J Salvat (Hôpitaux du Léman, Thonon-les-Bains), Profs E Pujade-Lauraine and J Alexandre, and Drs L Chauvenet and JM Tigaud (Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu, Paris), Dr J Meunier and D Bosquet (Centre Hospitalier Régional d’Orléans, Orléans), Dr J Cretin and E Roux (Clinique Bonnefon, Alès), Dr M Fabbro and P Champoiral (Institut du Cancer de Montpellier, Montpellier), Dr MN Certain and M Gillon (Centre Hospitalier d’Auxerre, Auxerre), Drs E Legouffe and M Armand (Clinique de Valdegour, Nîmes), Mrs I Gourmoud (Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées Sainte-Anne, Toulon), Drs C Ligeza-Poisson and P Deguiral, A Harel (Clinique Mutualiste de l’Estuaire, Saint-Nazaire), Dr C Tep and K Pietrain (Centre Hospitalier Départemental Les Oudairies, La Roche-sur-Yon), Dr F Rousseau and P Bensoussan (Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille), N Darchy (Hôpital Perpétuel Secours, Levallois-Perret), and G Marini (Centre Azuréen de Cancérologie, Mougins).

This work was supported by research grants from the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique 2006, 27–39) and La Fondation de France (grant #2006010589).

This work was presented as a poster at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 1–5, 2012.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MitchellAJChanMBhattiHPrevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studiesLancet Oncol201112216017421251875

- BelleraCARainfrayMMathoulin-PélissierSScreening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening toolAnn Oncol20122382166217222250183

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTWDepression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArch Intern Med2000160142101210710904452

- BlockSAssessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians – American Society of Internal MedicineAnn Intern Med2000132320921810651602

- GoodwinJSZhangDDOstirGVEffect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancerJ Am Geriatr Soc200452110611114687323

- WeinbergerMIBruceMLRothAJBreitbartWNelsonCJDepression and barriers to mental health care in older cancer patientsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2011261212621157847

- Lloyd-WilliamsMShielsCTaylorFDennisMDepression – an independent predictor of early death in patients with advanced cancerJ Affect Disord20091131–212713218558439

- SatinJRLindenWPhillipsMJDepression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysisCancer2009115225349536119753617

- PirlWFTraegerLGreerJADepression, survival, and epidermal growth factor receptor genotypes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancerPalliat Support Care201311322322923399428

- RaynerLPriceAEvansAValsrajKHotopfMHigginsonIJAntidepressants for the treatment of depression in palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysisPalliat Med2011251365120935027

- RaynerLPriceAHotopfMHigginsonIJThe development of evidence-based European guidelines on the management of depression in palliative cancer careEur J Cancer201147570271221211961

- EvansMMottramPDiagnosis of depression in elderly patientsAdv Psychiatr Treat200064956

- SöllnerWDeVriesASteixnerEHow successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling?Br J Cancer200184217918511161373

- LittleLDionneBEatonJNursing assessment of depression among palliative care cancer patientsJ Hosp Palliat Nurs20057298106

- KlapRUnroeKTUnützerJCaring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adultsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200311551752414506085

- MorleyJEThe top 10 hot topics in agingJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2004591243314718483

- FlahertyJHMcBrideMMarzoukSDecreasing hospitalization rates for older home care patients with symptoms of depressionJ Am Geriatr Soc199846131389434663

- NelsonCJChoCBerkARHollandJRothAJAre gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self-report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samplesJ Clin Oncol201028234835619996030

- WeinbergerMIRothAJNelsonCJUntangling the complexities of depression diagnosis in older cancer patientsOncologist2009141606619144682

- PassikSDDuganWMcDonaldMVRosenfeldBTheobaldDEEdgertonSOncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol1998164159416009552071

- MitchellAJVazeARaoSClinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysisLancet2009374969060961919640579

- MitchellAJRaoSVazeAInternational comparison of clinicians’ ability to identify depression in primary care: meta-analysis and meta-regression of predictorsBr J Gen Pract61583e72e8021276327

- RhondaliWHuiDKimSHAssociation between patient-reported symptoms and nurses’ clinical impressions in cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unitJ Palliat Med201215330130722339287

- MaguirePImproving the detection of psychiatric problems in cancer patientsSoc Sci Med19852088198234001990

- Lloyd-WilliamsMFriedmanTRuddNA survey of antidepressant prescribing in the terminally illPalliat Med199913324324810474711

- HotopfMChidgeyJAddington-HallJLyKLDepression in advanced disease: a systematic review Part 1. Prevalence and case findingPalliat Med2002162819711969152

- YennurajalingamSKwonJHUrbauerDLHuiDReyes-GibbyCCBrueraEConsistency of symptom clusters among advanced cancer patients seen at an outpatient supportive care clinic in a tertiary cancer centerPalliat Support Care201311647348023388652

- YennurajalingamSUrbauerDLCasperKLImpact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinicJ Pain Symptom Manage2011411495620739141

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- FalandryCWeberBSavoyeAMDevelopment of a geriatric vulnerability score in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with first-line carboplatin: a GINECO prospective trialAnn Oncol201324112808281324061628

- ClémentJPNassifRFLégerJMMarchanFDevelopment and contribution to the validation of a brief French version of the Yesavage Geriatric Depression ScaleEncephale19972329199 French9264935

- LépineJPGodchauMBrunPLempérièreTEvaluation of anxiety and depression among patients hospitalized on an internal medicine serviceAnn Med Psychol (Paris)19851432175189 French4037594

- LepineJPGodchauMBrunPAnxiety and depression in inpatientsLancet198528469–8470142514262867417

- GilFGrassiLTravadoLTomamichelMGonzalezJRSouthern European Psycho-Oncology Study GroupUse of distress and depression thermometers to measure psychosocial morbidity among southern European cancer patientsSupport Care Cancer200513860060615761700

- YesavageJABrinkTLRoseTLDevelopment and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary reportJ Psychiatr Res198219831713749

- BurkeWJNitcherRLRoccaforteWHWengelSPA prospective evaluation of the Geriatric Depression Scale in an outpatient geriatric assessment centerJ Am Geriatr Soc19924012122712301447439

- CrawfordGBRobinsonJAThe geriatric depression scale in palliative carePalliat Support Care20086321322318662414

- Lloyd-WilliamsMSpillerJWardJWhich depression screening tools should be used in palliative care?Palliat Med2003171404312597464

- HegelMTCollinsEDKearingSGillockKLMooreCPAhlesTASensitivity and specificity of the Distress Thermometer for depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer patientsPsychooncology200817655656017957755

- KeirSTCalhoun-EaganRDSwartzJJSalehOAFriedmanHSScreening for distress in patients with brain cancer using the NCCN’s rapid screening measurePsychooncology200817662162517973236

- JacobsenPBDonovanKATraskPCScreening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patientsCancer200510371494150215726544

- TrédanOGeayJFTouzetSGroupe d’Investigateurs Nation-aux pour l’Etude des Cancers OvariensCarboplatin/cyclophosph-amide or carboplatin/paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer? Analysis of two consecutive trials from the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers OvariensAnn Oncol200718225626217082510

- TisonPStructured interview guide for evaluating depression in elderly patients, adapted from DSM IV and the GDS, HDRS and MADRS scalesEncephale20002633343 French10951904

- KatzSAkpomCAA measure of primary sociobiological functionsInt J Health Serv197663493508133997

- LawtonMPBrodyEMAssessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily livingGerontologist1969931791865349366

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWJacksonBAJaffeMWStudies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial functionJAMA196318591491914044222

- CohenMEMarinoRJThe tools of disability outcomes research functional status measuresArch Phys Med Rehabil20008112 Suppl 2S21S2911128901

- DonovanKAJacobsenPBProgress in the implementation of NCCN guidelines for distress management by member institutionsJ Natl Compr Canc Netw201311222322623411388

- HollandJCBultzBDNational Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)The NCCN guideline for distress management: a case for making distress the sixth vital signJ Natl Compr Canc Netw2007513717323529

- JacobsenPBRansomSImplementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutionsJ Natl Compr Canc Netw2007519910317239329

- StukenbergKWDuraJRKiecolt-GlaserJKDepression screening scale validation in an elderly, community-dwelling populationPsychol Assess199022134138

- JadoonNAMunirWShahzadMAChoudhryZSAssessment of depression and anxiety in adult cancer outpatients: a cross-sectional studyBMC Cancer20101059421034465

- MackenzieLJCareyMLSanson-FisherRWD’EsteCAPaulCLYoongSLAgreement between HADS classifications and single-item screening questions for anxiety and depression: a cross-sectional survey of cancer patientsAnn Oncol201425488989524667721

- ColasantiVMarianettiMMicacchiFAmabileGAMinaCTests for the evaluation of depression in the elderly: a systematic reviewArch Gerontol Geriatr201050222723019414202

- FreyerGGeayJFTouzetSComprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a GINECO studyAnn Oncol200516111795180016093275

- CoscoTDDoyleFWardMMcGeeHLatent structure of the Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale: a 10-year systematic reviewJ Psychosom Res201272318018422325696

- CoyneJCvan SonderenENo further research needed: abandoning the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS)J Psychosom Res201272317317422325694

- DoyleFCoscoTConroyRWhy the HADS is still important: reply to Coyne and van SonderenJ Psychosom Res20127317778

- IbbotsonTMaguirePSelbyPPriestmanTWallaceLScreening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatmentEur J Cancer199430A137408142161