Abstract

Pathogens that cause health care-associated infections (HAIs) are known to survive on surfaces and equipment in health care environments despite routine cleaning. As a result, the infection status of prior room occupants and roommates may play a role in HAI transmission. We performed a systematic review of the literature evaluating the association between patients’ exposure to infected/colonized hospital roommates or prior room occupants and their risk of infection/colonization with the same organism. A PubMed search for English articles published in 1990–2014 yielded 330 studies, which were screened by three reviewers. Eighteen articles met our inclusion criteria. Multiple studies reported positive associations between infection and exposure to roommates with influenza and group A streptococcus, but no associations were found for Clostridium difficile, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Cryptosporidium parvum, or Pseudomonas cepacia; findings were mixed for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Positive associations were found between infection/colonization and exposure to rooms previously occupied by patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, but no associations were found for resistant Gram-negative organisms; findings were mixed for C. difficile, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and VRE. Although the majority of studies suggest a link between exposure to infected/colonized roommates and prior room occupants, methodological improvements such as increasing the statistical power and conducting universal screening for colonization would provide more definitive evidence needed to establish causality.

Introduction

Despite decades of infection prevention research and quality improvement initiatives, health care-associated infections (HAIs) remain common adverse events in hospitals and long-term care facilities.Citation1 Over 700,000 HAIs occur annually in the USA alone, leading to death in 6% of cases and costing the health care system 28–45 billion US dollars each year.Citation2–Citation4 Recently, there has been renewed interest in understanding the role of the physical environment in the spread of HAIs.Citation5,Citation6 Countless studies have reported that pathogenic organisms can survive on a variety of fomites in health care settings, including those at the patient bedside (eg, mattresses, linens, pillows, bed-frames, bedrails), inside patient bathrooms (eg, toilets, floors, soap dispensers), and on medical instruments (eg, blood pressure cuffs, suctioning systems).Citation7–Citation14 Moreover, the effectiveness of cleaning regimens has been called into question as a number of studies have reported that pathogens remain on hospital surfaces even after they have been disinfected in accordance with recommended protocols.Citation15–Citation18 Pathogens that survive on fomites can subsequently be transferred from contaminated surfaces to patients through direct contact, indirect contact through the hands and gloves of health care workers, or by aerosolization of surface particles.Citation8,Citation11,Citation19–Citation21

Patients hospitalized with infections frequently contaminate their surrounding environments with pathogenic organisms; therefore, roommates and previous room occupants may serve as potential sources of exposure to other patients.Citation8,Citation22 Yet, our understanding of how such exposures contribute to a patient’s overall risk of infection remains limited, and the effects of these exposures may be dependent on a variety of factors unique to each organism species, such as their robustness to atmospheric conditions, susceptibility to cleaning agents, and virulence. Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the literature describing organism transmission from concurrent roommates or previous room occupants in health care settings.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

This systematic literature review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.Citation23 Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) compared infection and/or colonization rates between patients known to be exposed to infectious roommates and/or prior room occupants and patients not known to be exposed, 2) were conducted in an acute or long-term health care setting, 3) were original research studies, 4) were published in English, and 5) were published from January 1, 1990 through December 31, 2014.

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted in February 2015 to ensure that all manuscripts published within the inclusion period had been indexed. All databases indexed within PubMed were searched using the following combination of keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) search terms linked with Boolean operators: ([MeSH {Patients’ Rooms}] AND [MeSH {Infection Control Practitioners} OR MeSH {Infection Control} OR MeSH {Cross Infection} OR MeSH {Infection} OR MeSH {Wound Infection} OR MeSH {Surgical Wound Infection} OR Keyword {Infection}]) OR (Keyword [Prior Room Occupant*]) OR (Keyword [Roommate] AND Keyword [Transmission] OR Keyword [Infection*] OR Keyword [Outbreak*]).

Article selection, review, and quality scoring

Three reviewers (BC, CCC, and BL) independently assessed each article at all stages of the review and quality scoring processes. Discrepancies among reviewers were discussed as a group until a consensus was reached. First, the reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all articles and eliminated those that were not relevant to the aims of the review. The remaining articles underwent full-text review to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. A hand search of the references of all articles meeting the inclusion criteria was also performed. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria were scored according to a modified 20-item version of the Checklist for Measuring Study Quality developed by Downs and Black ().Citation24 Some measures were not applicable to all articles; these items were removed from the score denominator and not assessed for studies in which they were not relevant. Final scores were converted to percentages.

Table 1 Assessment of study quality

Results

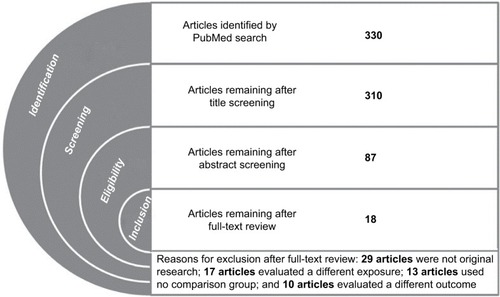

The database search returned 330 articles. No additional articles were identified from the hand search and no duplicates were found. Twenty articles were excluded during the title screening phase, and 223 articles were excluded during the abstract screening phase. The remaining 87 articles underwent full-text review, and 18 of these were determined to meet the inclusion criteria. describes the reasons for exclusion during the full-text review. Ten articles investigated the effects of exposure to infected or colonized roommates,Citation25–Citation34 six investigated the effects of exposure to infected or colonized prior room occupants,Citation35–Citation40 and two investigated both exposures.Citation41,Citation42

Figure 1 Identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of articles according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study designs and definitions of exposures and outcomes

The articles in this review represent a range of observational and interventional designs, including retrospective and prospective cohort studies (n=11),Citation26,Citation28–Citation32,Citation35,Citation38–Citation40,Citation42 case–control studies (n=4),Citation25,Citation27,Citation33,Citation34 and quasi-experimental studies (n=3).Citation36,Citation37,Citation41 The studies varied considerably in their definitions of exposure and outcome measures. Among studies that examined exposure to roommates with nonviral pathogens, four (44%) defined the exposure as having a roommate with a clinical infectionCitation25–Citation27,Citation42 and five (56%) defined the exposure as having a roommate who was either infected or colonized.Citation31–Citation34,Citation41 Among studies that examined exposure to previous room occupants, there was variation both in the determination of whether a previous occupant was infectious and in the timeframe during which they occupied the room. Four studies (50%) defined the exposure as a previous occupant who was infected or colonized,Citation35,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41 two studies (25%) – both of Clostridium difficile – defined the exposure as a previous occupant with a history of infection,Citation40,Citation41 and two studies (25%) did not specify.Citation36,Citation37

With regard to timing of the exposure, most of the studies implied that only the occupant immediately prior to the study subject was included, although only three articles stated this explicitly.Citation35,Citation37,Citation40 One study also analyzed exposure to any infectious patient who had occupied the same room within the previous 2-week period.Citation37 Finally, there was notable variation in the definition of study outcomes. Half of the articles used an outcome measure of infection,Citation25–Citation30,Citation32,Citation40,Citation42 while the other half used an outcome measure of infection or colonization.Citation31,Citation33–Citation39,Citation41 Methods of case detection ranged from universal screening to sampling based on clinical indication.

Findings of studies examining exposure to infected or colonized roommates

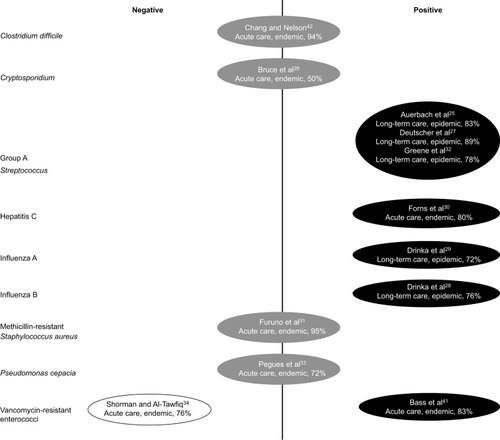

The 12 articles investigating the effects of exposure to infected or colonized roommates are described in and their findings are summarized in . Five studies evaluated bacterial pathogens that are transmitted by contact.Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation41,Citation42 No significant associations between roommate exposure and infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), C. difficile, or Pseudomonas cepacia were identified.Citation31,Citation33,Citation42 Results for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) were inconsistent, with Bass et alCitation41 reporting a statistically significant positive association (hazard ratio [HR]: 18.8, 95% confidence interval: [5.4–66.2]) and Shorman and Al-TawfiqCitation34 reporting a statistically significant negative association (odds ratio [OR]: 0.04 [0.004–0.4]).

Figure 2 Findings of studies investigating the association between health care-associated infection or colonization and exposure to infected or colonized roommates.

Table 2 Summary and quality assessment of studies reporting associations between health care-associated infection and exposure to infected or colonized roommates

Three studies conducted in long-term care settings examined group A streptococcus, which is transmitted by contact and droplet routes.Citation25,Citation27,Citation32 All three found significant positive associations between roommate exposure and infection, with ORs ranging from 2.0 (1.1–5.1) to 15.3 (2.5–110.9; point estimate not reported by Auerbach et alCitation25).

Three studies examined exposure to roommates infected with viral pathogens.Citation28–Citation30 Two studies of influenza conducted within the same long-term care facility found significantly elevated risks of infection among those with infected roommates (relative risk: 3.1 [1.6–5.8] for influenza A and relative risk: 2.6 [1.2–5.6] for influenza B).Citation28,Citation29 One study evaluated transmission of hepatitis C, a viral bloodborne pathogen, in a liver transplant ward of an acute care hospital and found significantly increased odds of infection after sharing a room with an infected patient (OR: 12.0 [1.4–103.0]).Citation30 One parasitic pathogen spread by fecal–oral contact, Cryptosporidium parvum, was evaluated in an acute care human immunodeficiency virus ward and no association was found.Citation26

Findings of studies examining exposure to rooms previously occupied by infected or colonized patients

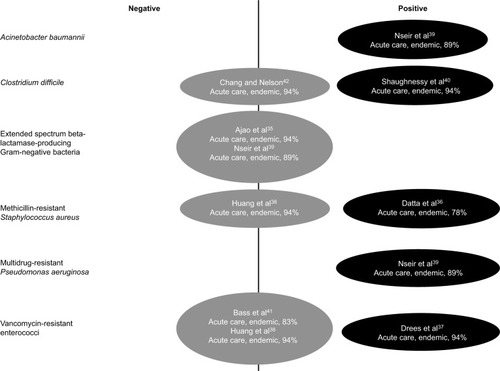

The eight articles investigating the effects of exposure to rooms previously occupied by infected or colonized patients are described in and their findings are summarized in . All of the articles studied bacterial pathogens spread through contact transmission in acute care hospitals, with all but twoCitation41,Citation42 taking place in intensive care units. Nseir et alCitation39 found that exposure to rooms previously occupied by patients with Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa resulted in significantly higher odds of infection or colonization (OR: 4.2 [2.0–8.8] and OR: 2.3 [1.2–4.3], respectively), while the two studies that examined extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing gram-negative organisms found no association.Citation35,Citation39 Effects of exposure to rooms previously occupied by patients with C. difficile, MRSA, and VRE were examined by at least two studies each. For each of these organisms, significant positive associations were reported by one article (C. difficile, HR: 2.4 [1.2–4.5];Citation40 MRSA, OR: 1.4 [p=0.04];Citation36 VRE, HR: 3.8 [2.0–7.4]Citation37), with the remainder of articles finding no significant associations.Citation38,Citation41,Citation42

Figure 3 Findings of studies investigating the association between health care-associated infection or colonization and exposure to infected or colonized prior room occupants.

Table 3 Summary and quality assessment of studies reporting associations between health care-associated infection and exposure to infected or colonized prior room occupants

Quality of included articles

Quality scores ranged from 50% to 95%, with the majority of articles scoring at or above 80% (median=83%, mean=82%). provides a summary of scores for each item. All of the articles had clearly stated aims, adequate descriptions of study populations, appropriate control groups, and acceptable reporting of results. However, many of the studies did not appropriately control for confounding (50%, n=9), address differential follow-up between exposed and unexposed patients (33%, n=6), or use acceptable statistical methods (17%, n=3). In addition, some articles did not include sufficient or precise definitions of the exposures (17%, n=3) or outcomes (6%, n=1) under investigation. Notably, none of the articles reported a sample size calculation indicating adequate power to detect differences between patients exposed versus unexposed to infected/colonized roommates or prior room occupants.

Discussion

More than half of the articles identified in this systematic literature review reported at least one statistically significant positive association between the infection/colonization status of a roommate or previous room occupant and the development of HAIs.25,Citation27–Citation30,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39–Citation41 Only a single article identified a statistically significant negative association.Citation34 The remainder found no associations that reached statistical significance, though this may be due to the fact that they were insufficiently powered; none of the articles reviewed included a statement indicating that statistical power was adequate for the analyses presented. Another factor that may have contributed to findings of no association is that many studies included patients who were either infected or colonized as potential sources of exposure. Patients with symptomatic infections may shed greater amounts of infectious body fluids to surrounding fomites, compared with patients who are asymptomatically colonized.Citation43 Therefore, if a causal association does indeed exist, including both infected and colonized patients as potential sources of exposure may have driven findings toward the null, since exposure to colonized roommates and prior room occupants could present less risk to patients. Heterogeneity of the exposure may have also arisen from variation in the infection or colonization site of a roommate or prior room occupant. In a study of patients with MRSA, environmental contamination was more prevalent on fomites surrounding patients with positive wound or urine cultures, compared with patients who had positive blood or sputum cultures.Citation8

The studies we reviewed revealed consistent findings for some pathogens (influenza, group A streptococcus) and inconsistent findings for others (VRE, MRSA, C. difficile). For endemic health care pathogens such as VRE, MRSA, and C. difficile, it may be difficult to isolate the effects of roommates and previous room occupants, since the exposure and outcome are common and may originate from multiple sources.Citation44 On the contrary, pathogens such as influenza and group A streptococcus are more commonly associated with outbreak scenarios, making it easier to single out the effects of particular exposures.Citation45 Other factors that may have contributed to inconsistent findings across studies are variations in how exposures and outcomes were defined and operationalized (eg, differences in case definitions, case finding methods, and timing of exposure).

While the inconsistency of findings for some of the organisms could be due to artifact, there may nevertheless be real differences in the effects of roommate and prior room occupant exposure based on the biologic characteristics of the infecting species. Microorganisms vary in their abilities to produce spores and survive changes to atmospheric temperature and moisture conditions.Citation46 In addition, some organisms favor specific sites of colonization or infection that may produce greater shedding of infectious material and higher potential for environmental contamination.Citation46 For example, a study of multidrug-resistant pathogens found that environmental contamination was more common surrounding patients with gram-positive versus gram-negative infections.Citation22 Furthermore, organism species differ in their resiliency to withstand cleaning agents and methods.Citation47,Citation48

The preponderance of evidence presented in this review suggests that there is a link between exposure to infected or colonized roommates and previous room occupants and the risk of HAIs. These findings present a number of practice and policy implications. First, the fact that patient rooms may serve as a reservoir for pathogens deposited by roommates and previous occupants highlights the importance of proper hand hygiene, not just for staff but for competent patients and their visitors as well.Citation49 To underscore this point, a molecular typing study demonstrated that 12% of patients who became newly colonized with MRSA while in the intensive care unit acquired a strain that most probably came from contamination in their immediate environment.Citation13 Second, these results emphasize the need for improved cleaning and disinfection of patient rooms, both during patients’ hospital stays and upon their discharge. For patients with known infection or colonization, targeted daily and terminal cleaning procedures that are tailored to specific organisms may reduce environmental contamination and infection rates.Citation50 Enhancement of routine cleaning measures should not be limited to patients with known infection or colonization, however, since patients may contaminate their environments during incubation periods before the infections are detected or when colonization is not detected through active surveillance.

There were some limitations to this systematic review. It is possible that some studies which would have met the inclusion criteria were not identified. Only databases indexed in PubMed were included, so any unpublished reports and other gray literature would not have been detected by our search. Similarly, studies that found significant positive associations may have been more likely to appear in the literature due to publication bias. Our restriction to articles published in English may have also excluded some relevant papers. While a major strength of this study is its coverage of two and a half decades of literature, changes in the epidemiology of HAIs, infection control policies and procedures, and study methodology over time may have introduced some variability to the studies we reviewed. Lastly, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis or provide a funnel plot because the studies assessed a wide variety of outcomes.

Notwithstanding these limitations, it is notable that the studies which reported significant findings were conducted across a range of institutions in several different countries across multiple decades. Presumably, the diverse study facilities employed a variety of cleaning products, methods, and infection control policies. Despite possible variations in practice, exposure to roommates and prior room occupants may have played a role in infection outcomes. Several gaps in the literature remain, however, specifically with regard to organisms that are endemic in health care settings and, therefore, difficult to associate with specific sources of exposure. The use of molecular typing would provide more definitive evidence concerning the role of roommates and prior room occupants in the epidemiology of HAIs.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at IDWeek 2015 as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “IDWeek 2015 Abstracts” in Open Forum Infectious Diseases: http://ofid.oxfordjournals.org/content/2/suppl_1/1706.full. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv133.1256

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HaleyRWShachtmanRHThe emergence of infection surveillance and control programs in US hospitals: an assessment, 1976Am J Epidemiol198011155745916990750

- KlevensRMEdwardsJRRichardsCLJrEstimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002Public Health Rep2007122216016617357358

- ScottRDIICenters for Disease Control and PreventionThe direct medical costs of healthcare-associated infections in U.S. hospitals and the benefits of prevention Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/hai/scott_costpaper.pdfAccessed October 1, 2015

- MagillSSEdwardsJRBambergWMultistate point- prevalence survey of health care-associated infectionsN Engl J Med2014370131198120824670166

- WeberDJRutalaWAMillerMBHuslageKSickbert-BennettERole of hospital surfaces in the transmission of emerging health care- associated pathogens: norovirus, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter speciesAm J Infect Control2010385 Suppl 1S25S3320569853

- WeberDJRutalaWAUnderstanding and preventing transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens due to the contaminated hospital environmentInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334544945223571359

- DuckroANBlomDWLyleEAWeinsteinRAHaydenMKTransfer of vancomycin-resistant enterococci via health care worker handsArch Intern Med2005165330230715710793

- BoyceJMPotter-BynoeGChenevertCKingTEnvironmental contamination due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: possible infection control implicationsInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol19971896226279309433

- SitzlarBDeshpandeAFertelliDKundrapuSSethiAKDonskeyCJAn environmental disinfection odyssey: evaluation of sequential interventions to improve disinfection of Clostridium difficile isolation roomsInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334545946523571361

- WilsonAPSmythDMooreGThe impact of enhanced cleaning within the intensive care unit on contamination of the near-patient environment with hospital pathogens: a randomized crossover study in critical care units in two hospitalsCrit Care Med201139465165821242793

- RayAJHoyenCKTaubTFEcksteinECDonskeyCJNosocomial transmission of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from surfacesJAMA2002287111400140111903026

- CreamerEHumphreysHThe contribution of beds to healthcare-associated infection: the importance of adequate decontaminationJ Hosp Infect200869182318355943

- HardyKJOppenheimBAGossainSGaoFHawkeyPMA study of the relationship between environmental contamination with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and patients’ acquisition of MRSAInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200627212713216465628

- GianniniMANanceDMcCullersJAAre toilet seats a vector for transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus?Am J Infect Control200937650550619243856

- GuerreroDMCarlingPCJuryLAPonnadaSNerandzicMMDons-keyCJBeyond the hawthorne effect: reduction of clostridium difficile environmental contamination through active intervention to improve cleaning practicesInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334552452623571372

- CarlingPCBriggsJHylanderDPerkinsJAn evaluation of patient area cleaning in 3 hospitals using a novel targeting methodologyAm J Infect Control200634851351917015157

- CarlingPCEvaluating the thoroughness of environmental cleaning in hospitalsJ Hosp Infect200868327327418289723

- AttawayHH3rdFaireySSteedLLSalgadoCDMichelsHTSchmidtMGIntrinsic bacterial burden associated with intensive care unit hospital beds: effects of disinfection on population recovery and mitigation of potential infection riskAm J Infect Control2012401090791222361357

- HessASShardellMJohnsonJKA randomized controlled trial of enhanced cleaning to reduce contamination of healthcare worker gowns and gloves with multidrug-resistant bacteriaInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334548749323571365

- BhallaAPultzNJGriesDMAcquisition of nosocomial pathogens on hands after contact with environmental surfaces near hospitalized patientsInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200425216416714994944

- DancerSJHospital cleaning in the 21st centuryEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis201130121473148121499954

- LemmenSWHäfnerHZolldannDStanzelSLüttickenRDistribution of multi-resistant gram-negative versus gram-positive bacteria in the hospital inanimate environmentJ Hosp Infect200456319119715003666

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementJ Clin Epidemiol2009621006101219631508

- DownsSHBlackNThe feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventionsJ Epidemiol Community Health19985263773849764259

- AuerbachSBSchwartzBWilliamsDOutbreak of invasive group A streptococcal infections in a nursing homeArch Intern Med19921525101710221580705

- BruceBBBlassMABlumbergHMLennoxJLdel RioCHorsburghCRJrRisk of Cryptosporidium parvum transmission between hospital roommatesClin Infect Dis200031494795011049775

- DeutscherMSchillieSGouldCInvestigation of a group A streptococcal outbreak among residents of a long-term acute care hospitalClin Infect Dis201152898899421460311

- DrinkaPJKrausePNestLGoodmanBMGravensteinSRisk of acquiring influenza A in a nursing home from a culture-positive roommateInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol2003241187287414649779

- DrinkaPJKrausePFNestLJGoodmanBMGravensteinSRisk of acquiring influenza B in a nursing home from a culture-positive roommateJ Am Geriatr Soc20055381437

- FornsXMartínez-BauerEFeliuANosocomial transmission of HCV in the liver unit of a tertiary care centerHepatology200541111512215619236

- FurunoJPShurlandSMZhanMComparison of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition among rehabilitation and nursing home residentsInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201132324424921460509

- GreeneCMVan BenedenCAJavadiMCluster of deaths from group A streptococcus in a long-term care facility – Georgia, 2001Am J Infect Control200533210811315761411

- PeguesDASchidlowDVTablanOCCarsonLAClarkNCJarvisWRPossible nosocomial transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia in patients with cystic fibrosisArch Pediatr Adolesc Med199414885088128180642

- ShormanMAl-TawfiqJARisk factors associated with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus in intensive care unit settings in Saudi ArabiaInterdiscip Perspect Infect Dis2013201336967424027580

- AjaoAOJohnsonKJHarrisADRisk of acquiring extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella species and Escherichia coli from prior room occupants in the intensive care unitInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334545345823571360

- DattaRPlattRYokoeDSHuangSSEnvironmental cleaning intervention and risk of acquiring multidrug-resistant organisms from prior room occupantsArch Intern Med2011171649149421444840

- DreesMSnydmanDRSchmidCHPrior environmental contamination increases the risk of acquisition of vancomycin-resistant enterococciClin Infect Dis200846567868518230044

- HuangSSDattaRPlattRRisk of acquiring antibiotic-resistant bacteria from prior room occupantsArch Intern Med2006166181945195117030826

- NseirSBlazejewskiCLubretRWalletFCourcolRDurocherARisk of acquiring multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli from prior room occupants in the intensive care unitClin Microbiol Infect20111781201120821054665

- ShaughnessyMKMicielliRLDePestelDDEvaluation of hospital room assignment and acquisition of Clostridium difficile infectionInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201132320120621460503

- BassPKarkiSRhodesDImpact of chlorhexidine-impregnated washcloths on reducing incidence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization in hematology-oncology patientsAm J Infect Control201341434534822980512

- ChangVTNelsonKThe role of physical proximity in nosocomial diarrheaClin Infect Dis200031371772211017821

- SiegelJDRhinehartEJacksonMChiarelloLHealthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Centers for Disease Control and PreventionManagement of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings2006 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/MDRO/MDROGuideline2006.pdfAccessed January 10, 2016

- SiegelJDRhinehartEJacksonMChiarelloLHealthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2007 guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/isolation/Isolation2007.pdfAccessed January 10, 2016

- WongSSYuenKYStreptococcus pyogenes and re-emergence of scarlet fever as a public health problemEmerg Microbes Infect201217e226038416

- DancerSJMopping up hospital infectionJ Hosp Infect19994328510010549308

- OtterJAFrenchGLSurvival of nosocomial bacteria and spores on surfaces and inactivation by hydrogen peroxide vaporJ Clin Microbiol200847120520718971364

- WeinsteinRAHotaBContamination, disinfection, and cross- colonization: are hospital surfaces reservoirs for nosocomial infection?Clin Infect Dis20043981182118915486843

- MorganDJRogawskiEThomKATransfer of multidrug-resistant bacteria to healthcare workers’ gloves and gowns after patient contact increases with environmental contaminationCrit Care Med20124041045105122202707

- ManianFAGriesnauerSBryantAImplementation of hospital-wide enhanced terminal cleaning of targeted patient rooms and its impact on endemic Clostridium difficile infection ratesAm J Infect Control201341653754123219675