Abstract

Background

Understanding differences in HIV incidence among people living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) can help inform strategies to prevent HIV infection. We estimated the time to HIV diagnosis among HCV-positive individuals and evaluated factors that could affect HIV-infection risk in this population.

Patients and methods

The British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort includes all BC residents (~1.5 million: about a third of all residents) tested for HCV and HIV from 1990 to 2013 and is linked to administrative health care and mortality data. All HCV-positive and HIV-negative individuals were followed to measure time to HIV acquisition (positive test) and identify factors associated with HIV acquisition. Adjusted HRs (aHRs) were estimated using Cox proportional-hazard regression.

Results

Of 36,077 HCV-positive individuals, 2,169 (6%) acquired HIV over 266,883 years of follow-up (overall incidence of 8.1 per 1,000 person years). Overall median (IQR) time to HIV infection was 3.87 (6.06) years. In Cox regression, injection-drug use (aHR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33–1.63), HBV infection (aHR 1.34, 95% CI 1.16–1.55), and being a man who has sex with men (aHR 2.78, 95% CI 2.14–3.61) were associated with higher risk of HIV infection. Opioid-substitution therapy (OST) (aHR 0.59, 95% CI 0.52–0.67) and mental health counseling (aHR 0.48, 95% CI 0.43–0.53) were associated with lower risk of HIV infection.

Conclusion

Injection-drug use, HBV coinfection, and being a man who has sex with men were associated with increased HIV risk and engagement in OST and mental health counseling were associated with reduced HIV risk among HCV-positive individuals. Improving access to OST and mental health services could prevent transmission of HIV and other blood-borne infections, especially in settings where access is limited.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HIV infection commonly co-occur because of shared transmission routes and risk behaviors. Globally, 2.7 million people have HIV–HCV coinfection, and of these 90% are among people who inject drugs (PWID).Citation1 HIV infection among HCV+ individuals is a major predictor of morbidityCitation2,Citation3 and mortality.Citation4,Citation5 Highly effective, well-tolerated, short-course, direct-acting antiviral agents with cure rates approaching 95% have revolutionized the treatment of HCV. These agents could prevent progressive liver disease and hence reduce morbidity and mortality. Prevention of HIV infection by addressing risk factors among people living with HCV or treated for HCV but potentially at risk of HIV could further reduce morbidity and mortality.

Risk factors for HCV coinfection among people living with HIV include injection-drug use (IDU),Citation6 alcohol use,Citation6,Citation7 unsafe sex among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM),Citation8,Citation9 and social disparities.Citation10 Potential preventive factors for HIV transmission, particularly among PWID, include opioid-substitution therapy (OST),Citation11,Citation12 mental health counseling, and other harm-reduction strategies.Citation12,Citation13 OST and mental health counseling have also been observed to reduce HCV reinfection among PWID.Citation14 However, data on risk factors for HIV among people living with HCV are limited, and the role of preventive factors has not been investigated. Coinfected individuals have multiple co-occurring infections and comorbidities; therefore, data on preventive factors for HIV infection from a real-world setting will inform programs that could reduce the burden of HIV among HCV-infected individuals. In this paper, we present an analysis of a large population-based cohort to estimate the risk of HIV and factors preventing and promoting this risk among people living with HCV in British Columbia.

Patients and methods

Study cohort

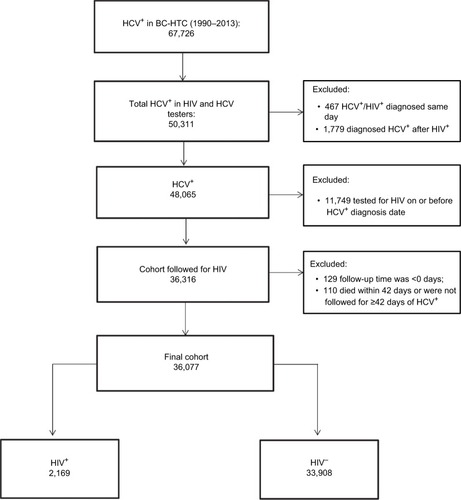

The British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC) includes all individuals (~1.5 million; approximately a third of all BC residents) tested for HCV or HIV at the BC Centre for Disease Control Public Health Laboratory (BCCDC-PHL) or diagnosed with HCV, HBV, HIV/AIDS, or active tuberculosis (TB). This cohort is linked with data on medical visits, hospitalizations, prescription drugs, cancers, and deaths ( and ). Almost all HIV and HCV testing in BC is performed at the BCCDC-PHL. All prescriptions dispensed in BC are recorded in a centralized system called PharmaNet, irrespective of the payer. Detailed characteristics of the cohort, including linkage and related data, are presented elsewhere.Citation15,Citation16 Data linkages were approved by the data stewards of the BCCDC, BCCDC-PHL, BC Ministry of Health, BC Vital Statistics Agency, and BC Cancer Registry. Approval for data linkage with the Ministry of Health data sets was granted under the BCCDC public health mandate to conduct surveillance and program evaluation. Data were deidentified before analyses.Citation15 This study was approved by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board (H15-01776) at the University of British Columbia.

Study population

Individuals diagnosed with HCV during 1990–2013 but negative for HIV were eligible for inclusion in this analysis. Individuals who tested positive for HCV and negative for HIV were followed for new diagnoses of HIV. A person’s time at risk started at HCV diagnosis and ended at HIV diagnosis, December 31, 2013 (end of follow-up), or death, whichever occurred earlier.

Outcome assessment

The outcome variable of interest was a time to HIV infection at least 6 weeks after HCV diagnosis. The date of HIV infection was estimated as the midpoint between the last HIV-negative test and the first HIV+ test.Citation11 All HCV+ individuals who tested positive for HIV on the same day or within 6 weeks of HCV diagnosis were excluded from the analysis.

Definitions

An individual testing positive for HCV antibodies, HCV RNA or genotype, or who had been reported as a case of HCV to public health was considered an “HCV case”.Citation15 Participants who were HCV-antibody+ at their first test on record were considered to have prevalent infection (HCV+-prevalent), while individuals with a negative test followed by a positive test were considered seroconverters (HCV+ seroconverters).Citation16 An individual included in provincial HIV/AIDS-surveillance data or who had a positive HIV laboratory test result was considered a case based on provincial HIV laboratory-test-interpretation guidelines. Additional HIV cases were ascertained through a validated algorithm requiring two medical visits or a hospitalization.Citation17 HBV and active TB diagnoses were based on provincial and national guidelines. Socioeconomic status was assessed using the Québec Index of Material and Social Deprivation, which is based on Canadian census data on small-area units.Citation18 The material component of the index includes indicators for education, employment, and income, whereas the social component comprises indicators related to marital status and family structure. Assessment of IDU, major mental illness, and problematic alcohol use was based on diagnostic codes for medical visits and hospitalizations in respective databases (). OST was based on prescriptions recorded in PharmaNet. IDU, problematic alcohol use, OST, and mental illnesses were evaluated across all data within the interval between HCV and HIV diagnosis and within 3 years of the first positive or last negative HIV or HCV test. Additionally, OST was evaluated as a time-varying covariate for this analysis. An individual was considered off OST if the interval between two successive prescriptions for OST was >28 days.Citation19 Mental health counseling was defined as any mental health-counseling visit during the follow-up period and was based on fee-item codes from a Medical Services Plan (medical visits; ). Mental health counseling includes services provided by a psychiatrist and comprises individual, family, and group therapy and telehealth services.

Data on sexual orientation were not available for all HCV+ individuals. We developed and validated an algorithm for identification of MSM status in a subset of data (n=5,382) on which sexual orientation variable was available. A model was developed to predict MSM status using penalized generalized linear model with testing patterns for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), previous STI diagnoses, substance use, visit to a clinic providing services to gay and other bisexual men, and residence in an area with higher percentage of MSM as predictor variables. The selected model had an area under the receiver-operating curve of 0.78%, 91.8% specificity, and 42.0% sensitivity.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of HCV+-prevalent and HCV+ seroconverters who were followed until HIV seroconversion were described separately. This stratification was done because our previous research showed differences in characteristics between these two populations.Citation16 HCV+-prevalent and HCV+ seroconverters are different in terms of demographic and risk factors. HCV+ seroconverters reflect ongoing risk activities, including IDU, while people with prevalent infection may not be engaged in high-risk activities, as shown in our previous work. HIV–HBV coinfection, major mental illness, illicit-drug use, problematic alcohol use, and socioeconomic deprivation are higher among HCV+ seroconverters than HCV+-prevalent individuals.Citation16 Therefore, transmission risk of HIV may be different in each of these groups, which were selected a priori for stratified analysis to account for differing baseline risk profiles of people. Incidence rates of HIV among HCV+ individuals (all, HCV+-prevalent, and HCV+ seroconverters) were calculated by dividing the number with HIV by person-years at risk. Cumulative-incidence curves were constructed comparing HIV incidence among various groups. Cox proportional-hazard regression analysis was conducted to assess the association of factors with HIV risk, and results summarized using HRs with corresponding 95% CIs. Analyses were performed in SAS/STAT software version 9.4 and R version 3.3.2.

Results

A total of 36,077 HCV+ individuals were eligible for inclusion in our study (). Of these, 33,908 (93.9%) had not acquired HIV infection and 2,169 (6.0%) had developed HIV infection during 266,883 person years of follow-up. Among HCV-infected individuals, 30,614 (84.8%) were HCV+-prevalent whereas 5,463 (15.1%) were HCV+ seroconverters (). A similar proportion of HIV cases were detected among HCV+ seroconverters (6.1%, 334 of 5,463) and HCV+-prevalent individuals (5.9%, 1,835 of 30,614).

Figure 1 Selection of participants for HIV infection analysis in British Columbia, Canada.

Table 1 Characteristics of HCV-diagnosed persons followed until time to HIV infection in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort

Distribution of characteristics across HIV and HCV groups

The majority of HCV-infected individuals were male: 66.6% of HCV+-prevalent individuals and 53.5% of HCV+ serocon-verters. Most of the HCV+-prevalent individuals were born during 1945–1964 (66.9%) and diagnosed between 35 and 54 years of age, whereas the majority of HCV+ seroconverters were born after 1964 (73.9%) and diagnosed between the ages of 25 and 44 years (). The majority of HCV+-prevalent individuals (86.8%) and HCV+ seroconverters (89.1%) lived in urban areas. The majority of HCV+ individuals were materially and socially deprived; however, HCV+ seroconverters were more socially (45.5% vs 38.7%: fifth quintile) and materially (32.5% vs 30.4%: fifth quintile) deprived than HCV+-prevalent individuals. A higher proportion of HCV+ seroconverters had a history of illicit drug use (57.9% vs 23.7%), IDU (40.5% vs 15.1%), and problematic alcoholic use (17.6% vs 10.4%) compared to HCV+-prevalent individuals. Similarly, compared to HCV+-prevalent individuals, HCV+ seroconverters had a higher proportion of major mental illnesses (22.9% vs 9.9%), depression (40.7% vs 23.5%), and psychosis (6.8% vs 2.7%). HBV was more commonly diagnosed in HCV+-prevalent individuals (5.6%) than HCV+ seroconverters (3.7%; ). A similar trend was observed for these factors within 3 years of the first positive or last negative HIV or HCV test ().

Incidence of HIV infection by HCV group

The overall HIV-incidence rate among HCV+ individuals was 8.1/1,000 person-years for a total of 266,883 person-years of follow-up. The HIV-incidence rate among HCV+ seroconverters was higher (10.2/1,000 person-years) compared to those with prevalent HCV infection (7.8/1,000 person-years) at diagnosis. Overall median (interquartile range [IQR]) time to HIV infection was 3.87 (6.06) years, shorter for seroconverters (3.63) years than prevalent HCV infections (3.95 years; ). Being male, having a history of IDU, mental illness, HBV, MSM status, younger age, and urban residence were associated with a higher incidence rate of HIV; however, the magnitude was lower among HCV+-prevalent individuals than HCV+ seroconverters. People on OST and receiving mental health counseling had lower HIV incidence for both HCV+ seroconverters and HCV+-prevalent individuals ().

Table 2 HIV incidence per 1,000 person-years by HCV group, BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort, 1990–2013

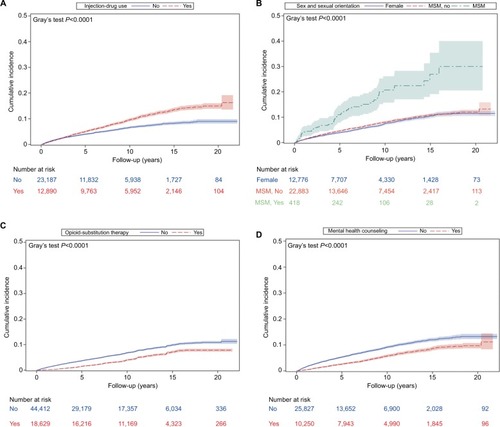

The cumulative incidence of HIV increased with time for both IDU and non-IDU, but the increase was steeper for IDU (P<0.0001; ). Cumulative incidence of HIV increased with time in MSM, but was similar between females and males who did not have sex with men (). For individuals who were on OST, the cumulative incidence of HIV was much lower than those who were not on OST and decreased with time (). The cumulative incidence of HIV increased with time among those who received mental health counseling, as well as among those who did not receive mental health counseling, but the increase was more pronounced in those who did not receive mental health counseling ().

Factors associated with risk of HIV infection among HCV-infected individuals

In the multivariable Cox proportional-hazard model for all HCV diagnoses, MSM status (adjusted HR 2.78, 95% CI 2.14–3.61), urban residence (adjusted HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.22–1.72), IDU (adjusted HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33–1.63), HBV (adjusted HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.16–1.55), and lower age at HCV diagnosis were significantly associated with increased risk of HIV infection. Conversely, being on OST (adjusted HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.52–0.67) and having received mental health counseling (adjusted HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.43–0.53) were associated with reduced risk of HIV (). In a sensitivity analysis conducted using the number of mental health-counseling visits per year, an increase in the number of visits was associated with a linear increase in the reduction of HIV risk for overall HCV+ and HCV+-prevalent individuals, but not for HCV+ seroconverters ().

Table 3 Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with time to HIV infection in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort

In the model restricted to HCV+ seroconverters, a similar pattern emerged as for all HCV diagnoses; however, the magnitude of the HRs was larger than in the model restricted to HCV+-prevalent individuals for MSM status and HBV infection (). No association was found between urban residence and HIV infection among HCV+ seroconverters. In analysis on HCV+-prevalent individuals, age at HCV diagnosis, urban residence, MSM, and IDU were significantly associated with risk of HIV infection. However, the strength of association for IDU and material deprivation was higher among HCV+-prevalent individuals than that for HCV+ seroconverters. In addition, the effect of OST and mental health counseling on risk of HIV infection was more pronounced among HCV+-prevalent individuals compared to HCV+ seroconverters (). The interaction of OST and mental health counseling was not significant (P=0.075). In addition, we evaluated the effectiveness of mental health counseling among HCV+ people with mental illness and without mental illness separately. Among people who had major mental illness, there was a 61% reduction in the risk of HIV compared to a 44% reduction in HIV risk among those who did not have history of major mental illness ().

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study in a setting of widespread OST availability, the incidence of HIV infection was higher among HCV+ seroconverters than HCV+-prevalent individuals. The risk of HIV infection was higher among MSM, PWID, urban residents, and those with HBV coinfection. OST and engagement in mental health counseling significantly reduced the risk of acquiring HIV infection. These interventions have important implications in prevention of HIV transmission in various settings globally.

Although earlier studies have identified a lower risk of HIV among PWID on OST,Citation11,Citation12 to our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association of OST and mental health counseling on the risk of HIV among HCV+ individuals in a large population-based cohort. We showed that OST was associated with a 41% reduction and mental health counseling with a 52% reduction in HIV risk among HCV+ individuals. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of OST and HIV transmission reported a 54% reduction in HIV risk among PWID,Citation12 whereas another study from BC on methadone maintenance therapy and HIV-infection risk reported a reduction of 36% among PWID.Citation11 However, both of these studies included PWID who did not have HCV infection or had not been tested for HCV. These interventions, coupled with other harm-reduction activities like syringe distribution and the expansion of safe injection sites, could have a major impact on HIV-infection risk among HCV+ populations, particularly PWID.

Currently, OST is available as a low-threshold treatment across most regions of BC for the management of opioid addiction. However, the availability of OST is limited in many settings, including developed and developing countries across the world. Globally, an estimated 6%–12% of PWID receive OST,Citation20 though coverage is even lower among countries with emerging epidemics of HIV among PWID. A survey of 21 of these countries from different regions of the world on HIV-prevention and treatment-service availability reported OST coverage of <3% among PWID.Citation21 In addition, mental health-services provision for the general population, especially in low- and middle-income countries is limited,Citation22 and is even lower for people with substance-use disorders,Citation23 particularly PWID. Data from the World Mental Health Survey estimate that only 1% of people with substance-use disorders in low-and middle-income countries have treatment coverage for these disorders.Citation23 Treatment of mental illnesses among PWID has been identified as an important part of HIV prevention.Citation24 In this context, mental health counseling plays an important role in HIV prevention. Psychotherapy, particularly behavioral interventions, similar to the effect of OST, has been shown to reduce HIV-acquisition risk in a number of studies on MSMCitation25 and PWID.Citation26,Citation27 However, varying evidence exists on the efficacy of single vs multiple psychosocial interventions and educational interventions. Some meta-analyses support single-session behavioral interventionsCitation28 for preventing STIs, including HIV, whereas another meta-analysis reported reduction in HIV-risk behavior in PWID with multiple sessions and educational interventions.Citation26 Our study provides evidence with respect to continued psychosocial support for reduction in HIV risk in a high-risk population of HCV-infected individuals. However, the linear relationship between reduction in HIV risk and the number of mental health-counseling visits was not apparent for HCV+ seroconverters (). As HCV+ seroconverters exhibit higher-risk behavior like active IDU, the effect of repeated mental health-counseling visits on reducing HIV risk may have been diluted. Additionally, individuals with more severe mental disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are less likely to attend followup visits for mental health care, due to mental illness-related stigma.Citation29,Citation30 HCV+ seroconverters in our study had a higher proportion of major mental illness, which includes disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and may have been less likely to continue with mental health counseling. However, all studies recommend a combination of HIV-prevention strategies to maximize the effect of psychosocial interventions on HIV-risk reduction.Citation25–Citation28 The availability and use of OST, along with mental health counseling and coupled with other harm-reduction interventions, could reduce the risk of such blood-borne infections as HIV, as shown in this study. Similar interventions have shown the potential to reduce the risk of HCV in previous research.Citation14,Citation31,Citation32

In our cohort, 6% of HCV-infected individuals developed HIV infection, with an incidence rate of 8.1/1,000 person years. However, there are no data on HIV incidence among HCV-infected populations. Studies reporting HIV incidence present estimates of 1.66–6.23/100 person-years among PWIDCitation33 and as high as 35.2/100 person-years among MSM.Citation34 This wider range of estimates could be due to differences in study populations, follow-up time, testing patterns, risk activities, and availability and impact of harm-reduction programs and interventions.

HCV+ seroconverters had a higher incidence of HIV infection compared to HCV+-prevalent individuals. This relates to differences in the magnitude of risk factors and population composition, which varied across these two groups. HCV+ seroconverters were younger, more socially and materially deprived, and had higher illicit-drug use, IDU, and major mental illnesses than HCV+-prevalent individuals. Seroconverters have higher-risk behavior, which is why they are followed for testing and detected as seroconverters, while prevalent infections represent a mix of high- and low-risk individuals. This may explain the difference between seroconverters and prevalent individuals in terms of magnitude of their risk activities.

In our study, being MSM was associated with a higher risk of HIV infection.Citation35 IDU and high-risk sexual behavior among MSM have been documented as major predictors for acquisition of HIV.Citation36 “Chemsex” or sexualized drug use among MSM has been associated with higher risk-taking behaviors and STIs, including HIV and HCV infection.Citation37 However, MSM among HCV+ seroconverters were at higher risk of HIV than MSM among HCV+-prevalent individuals. As stated, in our cohort, HCV+ seroconverters were younger and had a higher proportion of IDU, problematic alcohol use, and mental illness. Previous studies have reported a high incidence of HIV among young MSM,Citation38 especially related to drug useCitation39 and unprotected sex.Citation40 Services addressing substance use and mental illness in a stigma-free environment may reduce the risk of subsequent HIV infection among MSM.Citation41,Citation42

In our cohort, HIV indicator conditions, namely TB and HBV, were significantly associated with a higher risk of HIV.Citation43 Among these diseases, HBV has historically been a marker for behavior associated with potentially increased risk of HIV transmission. This represents an opportunity for early detection and treatment of HIV to reduce HIV-related morbidity and transmission.Citation44

Our outcome variable, time to HIV infection, also included individuals who did not have a last negative HIV test prior to a first HIV-positive test; however, a sensitivity analysis conducted after removal of these individuals yielded similar results as our main model (). Mental health counseling in BC is covered through a Medical Services Plan which includes all services that are billed by health care providers. However, if a service was provided without a fee from a service provider, then this information would not be captured and may lead to an underestimation of receipt of counseling services. Additionally, mental health counseling does not differentiate between the severity and type of mental illnesses/conditions and may not have the same effect in all high-risk populations. The major mental illness variable is based on a psychiatric visit, may include more severe mental illness diagnosis, and may underestimate mental illness and lead to misclassification of mental illness. Also, as these indicators are based on administrative databases, there is a possibility of misclassification. However, as expected, results showed stronger impact among those with mental illness compared to those without documented major mental illness (). The assessment of such risk factors as IDU and problematic alcohol use was based on diagnostic codes in administrative health-services databases. Our definitions were based on validations done previously;Citation45 however, there could be some misclassification and underestimation of effect. Furthermore, some of the interactions could not be evaluated, because of smaller samples, eg, MSM and IDU. All prescriptions that are dispensed in BC are recorded in a centralized system including OST, thereby capturing all dispensed OST. As causal inferences based on intervention effects in observational studies are prone to biases, future research using experimental designs is needed to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In this large population-based cohort of HCV-infected individuals, HCV+ seroconverters, PWID, MSM, and those coinfected with HBV had a higher risk of HIV infection, while OST and mental health counseling were associated with reduced risk of HIV. These data provide further support for the role of OST and mental health services in reducing transmission of blood-borne infections. Improving access to OST and mental health services could prevent transmission of HIV and other blood-borne infections, especially in settings where access is limited.

Author contributions

ZAB, NZJ, JAB, GO, RFB, MWT, MK, DG, MG, JW, and MM conceived the study. ZAB and NZJ designed the study. AY, NS, and SW assisted in data management. ZAB, NS, SW, and NZJ formulated the statistical analysis of the study. ZAB prepared the original draft of the paper. ZAB, NS, SW, MK, DG, MG, JW, AY, MA, HS, JAB, DR, TC, MM, MWH, GO, RFB, MWT, MK, and NZJ revised the paper critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of BCCDC, PHSA Performance Measurement and Reporting, Information Analysts, Ministry of Health Data Access, Research, and Stewardship, Medical Services Plan (MSP), Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) and Medical Beneficiary and Pharmaceutical Services program areas, BC Ministry of Health, and BC Cancer Agency and their staff involved in data access, procurement, and management. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this publication are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the BC Ministry of Health. This work was supported by the BC Center for Disease Control, agencies contributing data to the study, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grants PHE-141773 and NHC-142832). The funder had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary materials

Table S1 Criteria and data sources for the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC)

Table S2 Definitions for comorbid conditions in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC)

Table S3 Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with time to HIV infection in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort

Table S4 Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with time to HIV infection in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort stratified by major mental illness

Table S5 Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with time to HIV infection in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort

References

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]2014Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations)British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]Data Extract. MOH (2013) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]2014Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information FileBritish Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]Data Extract. MOH. (2013) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]2014PharmaCareBritish Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]Data Extract. MOH. (2013) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]2014PharmaNetBritish Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]Data Extract. MOH. (2013) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

- BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator]2014Vital Statistics DeathsBC Vital Statistics Agency [publisher]Data Extract. BC Vital Statistics Agency (2014) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]2014Client Roster (Client Registry System/Enterprise Master Patient Index)British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]Data Extract. MOH (2013) Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/conducting-health-research-evaluation/data-access-health-data-central

Disclosure

MK has received grant funding via his institution from Roche Molecular Systems, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, and Hologic. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationHIV and hepatitis coinfections2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/hepatitis/hepatitisinfo/enAccessed January 27, 2017

- Fernández-MonteroJVBarreiroPde MendozaCLabargaPSorianoVHepatitis C virus coinfection independently increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-positive patientsJ Viral Hepat2016231475226390144

- MocroftANeuhausJPetersLHepatitis B and C co-infection are independent predictors of progressive kidney disease in HIV-positive, antiretroviral-treated adultsPLoS One201277e4024522911697

- ButtZAWilkinsMJHamiltonETodemDGardinerJCSaeedMSurvival of HIV-positive individuals with hepatitis B and C infection in MichiganEpidemiol Infect2014142102131213924286128

- KleinMBRollet-KurhajecKCMoodieEEMortality in HIV-hepatitis C co-infected patients in Canada compared to the general Canadian population (2003-2013)AIDS201428131957196525259703

- SimonDMichitaRTBériaJUTietzmannDCSteinATLungeVRAlcohol misuse and illicit drug use are associated with HCV/HIV co-infectionEpidemiol Infect2014142122616262324512701

- BonaciniMAlcohol use among patients with HIV infectionAnn Hepatol201110450250721911892

- RauchARickenbachMWeberRUnsafe sex and increased incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: the Swiss HIV Cohort StudyClin Infect Dis200541339540216007539

- van de LaarTJvan der BijAKPrinsMIncrease in HCV incidence among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam most likely caused by sexual transmissionJ Infect Dis2007196223023817570110

- RourkeSBSobotaMTuckerRSocial determinants of health associated with hepatitis C co-infection among people living with HIV: results from the Positive Spaces, Healthy Places studyOpen Med201153e120e13122046224

- AhamadKHayashiKNguyenPEffect of low-threshold methadone maintenance therapy for people who inject drugs on HIV incidence in Vancouver, BC, Canada: an observational cohort studyLancet HIV2015210e445e45026423652

- MacarthurGJMinozziSMartinNOpiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysisBMJ2012345e594523038795

- KerrTSmallWBuchnerCSyringe sharing and HIV incidence among injection drug users and increased access to sterile syringesAm J Public Health201010081449145320558797

- IslamNKrajdenMShovellerJIncidence, risk factors, and prevention of hepatitis C reinfection: a population-based cohort studyLancet Gastroenterol Hepatol20172320021028404135

- JanjuaNZKuoMChongMAssessing hepatitis C burden and treatment effectiveness through the British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC): design and characteristics of linked and unlinked participantsPLoS One2016113e015017626954020

- JanjuaNZYuAKuoMTwin epidemics of new and prevalent hepatitis C infections in Canada: BC Hepatitis Testers CohortBMC Infect Dis20161633427436414

- NosykBColleyGYipBApplication and validation of case-finding algorithms for identifying individuals with human immunodeficiency virus from administrative data in British Columbia, CanadaPLoS One201381e5441623382898

- PampalonRHamelDGamachePPhilibertMDRaymondGSimpsonAAn area-based material and social deprivation index for public health in Québec and CanadaCan J Public Health20121038 Suppl 2S17S2223618066

- NosykBMacnabYCSunHProportional hazards frailty models for recurrent methadone maintenance treatmentAm J Epidemiol2009170678379219671835

- MathersBMDegenhardtLAliHHIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverageLancet20103759719 1014102820189638

- PetersenZMyersBvan HoutMCPlüddemannAParryCAvailability of HIV prevention and treatment services for people who inject drugs: findings from 21 countriesHarm Reduct J2013101323957896

- RathodSPinnintiNIrfanMMental health service provision in low- and middle-income countriesHealth Serv Insights201710117863291769435

- DegenhardtLGlantzMEvans-LackoSEstimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: an analysis of data from the World Mental Health SurveysWorld Psychiatry201716329930728941090

- BuckinghamESchrageECournosFWhy the treatment of mental disorders is an important component of HIV prevention among people who inject drugsAdv Prev Med2013201369038623401785

- KoblinBChesneyMCoatesTEffects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled studyLancet20043649428415015234855

- MeaderNSemaanSHaltonMAn international systematic review and meta-analysis of multisession psychosocial interventions compared with educational or minimal interventions on the HIV sex risk behaviors of people who use drugsAIDS Behav20131761963197823386132

- GilchristGSwanDWidyaratnaKA systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce drug and sexual blood borne virus risk behaviours among people who inject drugsAIDS Behav20172171791181128365913

- EatonLAHuedo-MedinaTBKalichmanSCMeta-analysis of single-session behavioral interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: implications for bundling prevention packagesAm J Public Health201210211e34e4422994247

- LawrenceDKiselySInequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illnessJ Psychopharmacol2010244 Suppl616820923921

- KnaakSSzetoAFitchKModgillGPattenSStigma towards borderline personality disorder: effectiveness and generalizability of an anti-stigma program for healthcare providers using a pre-post randomized designBorderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul20152926401311

- HaganHPougetERdes JarlaisDCA systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugsJ Infect Dis20112041748321628661

- TurnerKMHutchinsonSVickermanPThe impact of needle and syringe provision and opiate substitution therapy on the incidence of hepatitis C virus in injecting drug users: pooling of UK evidenceAddiction2011106111978198821615585

- AspinallEJNambiarDGoldbergDJAre needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Epidemiol201443123524824374889

- SandersEJOkukuHSSmithADHigh HIV-1 incidence, correlates of HIV-1 acquisition, and high viral loads following seroconversion among MSMAIDS201327343744623079811

- BiniEJCurrieSLShenHNational multicenter study of HIV testing and HIV seropositivity in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infectionJ Clin Gastroenterol200640873273916940888

- BeyrerCBaralSDvan GriensvenFGlobal epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with menLancet2012380983936737722819660

- HegaziALeeMJWhittakerWChemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinicsInt J STD AIDS201728436236627178067

- BalajiABBowlesKELeBCPaz-BaileyGOsterAMHigh HIV incidence and prevalence and associated factors among young MSM, 2008AIDS201327226927823079807

- FreemanPWalkerBCHarrisDRMethamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US citiesArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2011165873674021810635

- MustanskiBSNewcombMEdu BoisSNGarciaSCGrovCHIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventionsJ Sex Res2011482–321825321409715

- JohnsonWDDiazRMFlandersWDBehavioral interventions to reduce risk for sexual transmission of HIV among men who have sex with menCochrane Database Syst Rev20083CD001230

- HerbstJHBeekerCMathewAThe effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic reviewAm J Prev Med2007324 Suppl386717218189

- SøgaardOSLohseNØstergaardLMorbidity and risk of subsequent diagnosis of HIV: a population based case control study identifying indicator diseases for HIV infectionPLoS One201273e3253822403672

- JooreIKArtsDLKruijerMJHIV indicator condition-guided testing to reduce the number of undiagnosed patients and prevent late presentation in a high-prevalence area: a case-control study in primary careSex Transm Infect201591746747226126531

- JanjuaNZIslamNKuoMIdentifying injection drug use and estimating population size of people who inject drugs using healthcare administrative datasetsInt J Drug Policy201855313929482150