Abstract

Objective

To evaluate recent trends in the prevalence and impact of comorbidity on colorectal cancer (CRC) survival in the Central Region of Denmark.

Material and methods

Using the Danish National Registry of Patients, we identified 5,777 and 2,964 patients with a primary colon or rectal cancer, respectively, from 2000 through 2011. We estimated survival according to Charlson Comorbidity Index scores and computed mortality rate ratios (MRRs) using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, adjusting for age and sex.

Results

More than one-third of CRC patients had comorbidity at diagnosis. During the study period, 1-year survival increased substantially in colon cancer patients with Charlson score 0 (72% to 80%) and modestly for Charlson score 3+ patients (43% to 46%). Using colon cancer patients with Charlson score 0 as reference, adjusted 1-year MRRs in patients with Charlson score 3+ were 2.19 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.57–3.05) in 2000–2002 and 2.56 (95% CI: 1.96–3.35) in 2009–2011. One-year survival after rectal cancer improved from 81% to 87% in patients with Charlson score 0 and from 56% to 60% in Charlson score 3+. Corresponding MRRs in patients with Charlson 3+ were 2.21 (95% CI: 1.33–3.68) in 2000–2002 and 3.09 (95% CI: 1.91–5.00) in 2009–2011 using Charlson score 0 as reference. Five-year MRRs did not differ substantially from 1-year MRRs.

Conclusion

Comorbidity was common among CRC patients and was associated with poorer prognosis. We observed improved survival from 2000 to 2011 for all comorbidity levels, with least improvement for colon cancer patients with comorbid conditions.

Background

Worldwide, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death.Citation1 CRC incidence increases sharply with ageCitation2 as do the prevalence of chronic diseases.Citation3 Consequently, a large proportion of CRC patients suffer from one or more comorbid conditions at the time of their cancer diagnosisCitation4–Citation6 which may affect their diagnostic work up, treatment options, and prognosis.Citation7,Citation8 Several studies indicate that CRC patients with coexisting diseases have a poorer survival compared to those without.Citation4,Citation6,Citation8–Citation10

Due to population aging, the proportion of elderly cancer patients is increasing.Citation11 The challenge in cancer treatment that comorbidity, physiologic, and functional frailty in these aging patients may pose will thus increase in the future.Citation12

Monitoring trends in CRC survival is urgent for optimizing clinical cancer care and outcomes. Despite knowledge that coexisting diseases affect CRC prognosis, only a few studies incorporate comorbidity in survival trends.Citation4,Citation5 Previous Danish research reported improved 1- and 5-year survival for colon cancer patients with Charlson score 3+ during 1995–2006, whereas for rectal cancer patients with similar Charlson scores, 1-year survival was stable.Citation4 In the present population-based study we examine the most recent changes in the prevalence and the impact of comorbidity on survival and mortality in a cohort of CRC patients diagnosed during 2000–2011 using Danish medical registry data.

Material and methods

Study population

We conducted this population-based cohort study in the Central Denmark region, which has 1.2 million inhabitants.Citation13 The Danish National Health Service provides universal, tax-supported health care, guaranteeing unfettered access to general practitioners and hospitals and partial reimbursement for prescribed drugs. Accurate and unambiguous linkage of all registries at the individual level is possible in Denmark by means of the unique personal registry number assigned to each Danish citizen at birth or immigration.

Identification of patients with CRC

We identified all patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-8 code 153–154.09 and ICD-10 code C18-19) and rectal cancer (ICD-8 code 154.10-154.29 and ICD-10 code C20) from January 1, 1995 through December 31, 2011, using the Danish National Registry of Patients (NRP). The NRP contains records of all non-psychiatric hospital admissions since 1977 and outpatient hospital visits since 1995. Information includes the patient’s civil registration number, dates of admission and discharge, and up to 20 discharge diagnoses, coded by physicians according to the 8th revision of the International Classification of Diseases until the end of 1993, and the 10th revision thereafter.Citation14 Patients with a previous diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer were excluded from the cohort.

Comorbidity at diagnosis

From the NRP, we obtained information on pre-existing comorbidity 10 years prior to the date of CRC diagnosis using the Charlson Index. This index comprises 19 disease categories each assigned between one and six points according to the adjusted risk of 1-year mortality.Citation15,Citation16 We used the sum of these points (ie, the Charlson score) to categorize patients. CRC diagnoses were excluded when we computed the Charlson score, as were all cancer diagnoses within 60 days before the CRC cancer diagnosis, in order to eliminate possible nonspecific cancer diagnoses related to the CRC cancer diagnosis. We grouped patients according to their level of comorbidity: (1) Charlson score = 0; (2) Charlson score = 1–2; and (3) Charlson score 3+.

Vital status

We linked members of the study cohort via their personal registry number to the Danish Civil Registration System to obtain vital status.Citation17 This registry has recorded all changes in vital status and migration for the entire Danish population since 1968, with daily electronic updates. Follow-up was through patient date of death or emigration or December 31, 2011, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

We computed the prevalence of comorbidity in CRC patients during four 3-year study periods: 2000–2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2008, and 2009–2011. We constructed Kaplan–Meier survival curves for CRC patients according to Charlson score and study periods. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute 1- and 5-year crude and age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios as a measure of relative mortality to assess the association of comorbidity with mortality using the Charlson score of 0 as a reference in each time period. In the latter periods, we estimated 1- and 5-year survival using a hybrid analysis in which survival was estimated using the survival experience of patients in the previous periods.Citation18 CRC stage and treatment was considered as a causal intermediate and therefore not included in the analyses.Citation19 All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number 2006-53-1346).

Results

Colon cancer

Prevalence of comorbidity

A total of 5,777 patients were diagnosed with colon cancer during 2000–2011 of which 48% were men (). For both sexes, colon cancer incidence increased over time. The prevalence of patients with Charlson score 0 decreased from 66% to 62% during the time period, with a corresponding increase in the prevalence of patients with Charlson score 3+ (4%). Overall median age at diagnosis was 72 years and did not change during the study period. Patients with Charlson score 0 had the lowest median age which decreased from 71 to 69 years during the study period. Accordingly, median age increased for patients with a Charlson score 1–2 (from 75 to 76 years) and Charlson score 3+ (from 74 to 78 years).

Table 1 Characteristics of colon and rectal cancer patients in the Central Region of Denmark 2000–2011

Survival

Overall 1-year survival gradually improved from 68% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 65%–70%) in 2000–2002 to 73% (95% CI: 71%–75%) in 2009–2011 corresponding to an adjusted mortality rate ratio (MRR) of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.64–0.85) in 2009–2011 using 2000–2002 as a reference (). Accordingly, the overall 5-year survival improved from 39% (95% CI: 37%–42%) to a predicted survival of 46% (95% CI: 43%–48%) for those diagnosed in 2009–2011, corresponding to a 5-year adjusted MRR of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.69–0.84) compared to 2000–2002.

Table 2 Overall survival and mortality rate ratios after colon and rectal cancer according to diagnostic calendar periods in the Central Region of Denmark 2000–2011

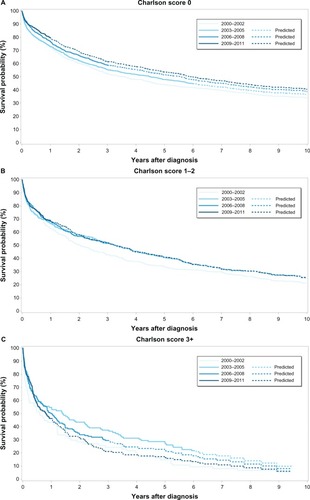

shows survival curves for colon cancer patients within each comorbidity group according to time period. Survival among patients with Charlson score 0 improved during the study period while the survival remained virtually unchanged for patients with Charlson score 1–2 diagnosed from 2003–2005 onwards ( and ). In patients with Charlson score 3+, survival peaked in 2003–2005, but beyond 1-year of follow-up the predicted survival in the 2009–2011 period was even poorer than among patients diagnosed in 2003–2005 and 2006–2008 ().

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier curves for colon cancer patients in the Central Region of Denmark for four diagnostic periods for (A) Charlson score = 0, (B) Charlson score = 1–2, and (C) Charlson score = 3+.

Across all time periods, absolute survival decreased with increasing Charlson score and 5-year absolute survival among patients with Charlson scores 3+ was approximately half of that for patients with Charlson score 0 (). During the study period, survival improved in all comorbidity groups. From 2000–2002 to 2009–2011, 1-year survival improved among patients with Charlson score 0 (72% [95% CI: 69%–75%] to 80% [95% CI: 77%–82%]) as did 5-year survival (44% [95% CI: 41%–47%] to predicted 53% [95% CI: 50%–56%]). Similarly, 1- and 5-year survival improved among patients with Charlson score 1–2 and 3+ from 2000–2002 to 2009–2011, mainly due to substantial improvement from 2000–2002 to 2003–2005. Thus, from the period 2003–2005 on, survival appeared to stabilize in these patients. We observed that patients with comorbidity had poorer survival than those with no comorbidity in each diagnostic period (). Also, we noted a tendency that the relative mortality increased slightly from the first to the last time periods, although differences were not statistically significant. One-year adjusted MRRs for patients with Charlson score 1–2 ranged from 1.19 (95% CI: 0.96–1.47) to 1.43 (95% CI: 1.14–1.80), and 5-year adjusted MRRs ranged from 1.20 (95% CI: 1.02–1.40) to 1.26 (95% CI: 1.08–1.46), using patients with Charlson score 0 as a reference. Corresponding 1- and 5-year adjusted MRRs for patients with Charlson score 3+, ranged from 2.19 (95% CI: 1.57–3.05) to 2.56 (95% CI: 1.96–3.35) and 2.10 (95% CI: 1.61–2.74) to 2.30 (95% CI: 1.89–2.80), respectively.

Table 3 One-year and 5-year survival and relative mortality after colon cancer according to comorbidity level for each diagnostic period in the Central Region of Denmark 2000–2011

Rectal cancer

Prevalence of comorbidity

Of the 2,964 rectal cancer patients diagnosed during the study period, 56% were men (). Incident rectal cancer increased only slightly over time. Patients with Charlson score 0 accounted for 72% in 2000–2002 and 66% in 2009–2011 with corresponding increases in the prevalence of patients with Charlson score 1–2 (3%) and 3+ (2%). Overall median age at diagnosis was 69 years. Patients with Charlson score 0 had the lowest median age and only a minor decrease was observed over time (from 68 to 67 years), whereas the median age increased slightly for patients with Charlson score 3+ (from 76 to 77 years).

Survival

Overall 1-year survival after rectal cancer improved from 77% (95% CI: 74%–80%) in 2000–2002 to 80% (95% CI: 77%–82%) in 2009–2011 with a corresponding adjusted MRR of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.68–1.05) using 2000–2002 as a reference (). Accordingly, the overall 5-year survival improved from 46% (95% CI: 42%–50%) to a predicted 49% (95% CI: 45%–52%) during the study period, corresponding to an adjusted MRR of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.79–1.05) in 2009–2011 as compared to 2000–2002.

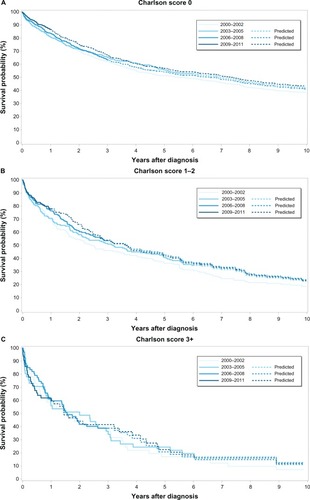

Survival improved slightly within each comorbidity level during the study period, although patients with Charlson score 3+ had a poorer 1-year survival in the 2009–2011 period compared to the previous calendar period (–).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curves for rectal cancer patients in the Central Region of Denmark for four diagnostic periods for (A) Charlson score = 0, (B) Charlson score = 1–2, and (C) Charlson score = 3+.

As for colon cancer, survival after rectal cancer decreased with the burden of comorbidity in all diagnostic periods, in particular the 5-year survival (). For patients with Charlson score 3+, 5-year survival was less than half of that for patients with Charlson score 0. During the 2000–2011 period survival improved in all comorbidity groups, although for patients with Charlson score 3+ the 5-year survival was almost unchanged from 2003 throughout the study period.

Table 4 One-year and 5-year survival and relative mortality after rectal cancer according to comorbidity level for each diagnostic period in the Central Region of Denmark 2000–2011

Compared to patients with Charlson score 0 the MRRs increased with increasing level of comorbidity in each calendar period (). One- and 5-year adjusted MRRs were almost unchanged from the first to the last time periods.

Discussion

In this population-based study, more than one-third of the CRC patients had documented comorbid conditions according to the Charlson Index and the overall prevalence of comorbidity increased slightly over the 12-year study period. Comorbidity was a strong negative prognostic factor even after adjusting for age. From 2000–2002 to 2009–2011, CRC survival improved within each level of comorbidity, mainly due to an apparent large improvement until 2003–2005, after which survival stagnated among colon cancer patients with comorbid conditions, from 2003 through 2011. During this time period, the relative mortality was almost unchanged for rectal cancer patients, whereas for colon cancer patients the relative mortality seemed to increase weakly.

The increasing prevalence of comorbidity among patients with CRC over the study period may be attributable to demographic changes in terms of population aging or to closer medical follow-up of patients with chronic conditions leading to the detection of more CRC cases. Also, the introduction of an accounting method based on Diagnosis Related Groups in 2000 by the Danish health care authorities may have led to more complete recording of concurrent diseases in addition to the main condition. Still, the prevalence of comorbidity in CRC patients was higher in a recent Dutch study by van Leersum et alCitation5 than in our study. In that study, the proportion of CRC patients with comorbid conditions according to the Charlson Index increased from 47% in 1995 to 62% in 2010. However, their comorbidity data had been assessed in part from medical hospital records and also from referral letters from general practitioners. Because we used discharge diagnoses in the NRP, we had no information on chronic diseases treated solely at the general practitioners; eg, hypertension, diabetes and pulmonary diseases, which were the most frequent conditions in the Dutch study.

In agreement with previous research, we found that CRC patients with comorbidity had a poorer survival than those without comorbidity.Citation4,Citation6,Citation8–Citation10 Several mechanisms may explain the disparity in survival. First, severe comorbidity affects risk of mortality independent of the cancer,Citation6 especially when the mortality burden of the cancer is low.Citation20 Second, comorbidity may delay CRC diagnosis by masking symptoms of the cancer, leading to late stage disease and poor prognosis. However, closer medical follow-up of comorbid patients could also lead to cancer detection at earlier stages.Citation21 Third, treatment strategies may be influenced by the burden of comorbidity. Frail patients may undergo less extensive surgery, and it has been reported that CRC patients with concomitant diseases receive less adjuvant therapy compared with those without.Citation7,Citation8,Citation22 Fourth, interaction between comorbidity and the cancer may accelerate the course of the cancer.Citation23

The overall survival from CRC improved in Denmark from 2000 through 2011. The current observations thus agree with previous trends,Citation4,Citation24–Citation26 although most studies did not incorporate comorbidity in their analyses. We noted a stagnating survival among colon cancer patients with coexisting diseases from 2003 onward, which discords with concurrent improvements in rectal cancer as well as previous observations.Citation4 However, this apparent stagnation may in part have been caused by substantial improvements in survival among comorbid patients in the period between 2003–2005. During the study period, the surgical treatment of CRC was gradually centralized,Citation27 facilitating higher hospital procedure volume and probably higher surgeon case volume across all levels of comorbidities. Still, in the Region of Central Denmark, colon cancer is treated at more hospitals than rectal cancer.Citation2 Moreover, only rectal cancer is included in multidisciplinary teams comprised of radiologists, pathologists, surgeons, and oncologists, which has the potential to improve the outcome.Citation28 We can only speculate whether this disparity in the management of colon and rectal cancer diagnostics and treatment may contribute to the discrepancy in survival.

Strengths of our study include a population-based design within the setting of a uniformly organized health care system. Our cohort was well-defined by the use of computerized registries with complete follow-up.Citation14,Citation17,Citation29 Our study also had limitations; for instance, we used the Charlson Index to measure comorbidity, which has been tested reliable and valid.Citation16,Citation30 The positive predictive value of the NRP coding of the Charlson conditions has been demonstrated consistently high.Citation31 However, the Charlson Index does not make allowance for the severity of the diseases. Thus, patients with identical scores may differ substantially in their functional impairment, which could influence mortality.Citation32

We lacked data on cancer stage, which might have been unevenly distributed among the comorbidity groups. Likewise, we lacked data on treatment, which could conceivably vary with the burden of comorbidity.Citation33 Although both stage and treatment are prognostically important factors, they are causal intermediates and should not be adjusted for in the analyses. Moreover, according to the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group database, the stage distribution among CRC patients has not changed substantially between 2001 and 2011.Citation2 Therefore, improvements in survival are less likely to stem from diagnosis at earlier stages over time. Also, we had no data on tumor histopathology. However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence of an association between comorbidity and tumor morphology, such as histologic subtype or grade. Morphology, therefore, should not bias our estimates. From the registries we had no information on structural factors, eg, increased hospital volume and population aging and potential confounders, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity. Finally, we only examined all-cause mortality and not disease-specific mortality. Nonetheless, given the difficulty of disentangling whether CRC itself, cancer complications, or underlying comorbidity contributed to mortality, we conclude that all-cause mortality is a valid measure.

In conclusion, we found that comorbidity was present in more than one-third of CRC patients and had a substantial negative impact on prognosis. Despite improved overall survival during 2000–2002 to 2009–2011 period, survival improvement was least in colon cancer patients with comorbid conditions. Due to an increasing proportion of elderly (comorbid) cancer patients, our findings warrant clinical and public attention.

Acknowledgments

Cancer analyses in the Central Denmark Region were conducted as part of the AUDEO (Aarhus University Disease Epidemiology and Outcomes) Project at the Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FerlayJShinHRBrayFFormanDMathersCParkinDMEstimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008Int J Cancer2010127122893291721351269

- Danish Colorecal Cancer GroupNationwide database of colorectal cancer: annual report 2010CopenhagenDCCG2011 Danish

- PiccirilloJFVlahiotisABarrettLBFloodKLSpitznagelELSteyerbergEWThe changing prevalence of comorbidity across the age spectrumCrit Rev Oncol Hematol200867212413218375141

- IversenLHNørgaardMJacobsenJLaurbergSSørensenHTThe impact of comorbidity on survival of Danish colorectal cancer patients from 1995 to 2006 – a population-based cohort studyDis Colon Rectum2009521717819273959

- van LeersumNJJanssen-HeijnenMLWoutersMWIncreasing prevalence of comorbidity in patients with colorectal cancer in the South of the Netherlands 1995–2010Int J Cancer201313292157216323015513

- GrossCPGuoZMcAvayGJAlloreHGYoungMTinettiMEMultimorbidity and survival in older persons with colorectal cancerJ Am Geriatr Soc200654121898190417198496

- ChenRCRoyceTJExtermannMReeveBBImpact of age and comorbidity on treatment and outcomes in elderly cancer patientsSemin Radiat Oncol201222426527122985808

- LemmensVEJanssen-HeijnenMLVerheijCDHoutermanSRepelaer van DrielOJCoeberghJWCo-morbidity leads to altered treatment and worse survival of elderly patients with colorectal cancerBr J Surg200592561562315779071

- SarfatiDHillSBlakelyTThe effect of comorbidity on the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival from colon cancer: a retrospective cohort studyBMC Cancer2009911619379520

- YancikRWesleyMNRiesLAComorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based studyCancer19988211212321349610691

- YancikRRiesLACancer in older persons: an international issue in an aging worldSemin Oncol200431212813615112144

- BalducciLExtermannMManagement of cancer in the older person: a practical approachOncologist20005322423710884501

- Population at the first day of the quater by municipality, sex, age, marital status, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship – StatBank Denmark –data and statistics Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/stat-bank5a/SelectVarVal/Defne.asp?MainTable=FOLK1&PLanguage=1&PXSId=0&wsid=cftreeAccessed December 12, 2012

- LyngeESandegaardJLReboljMThe Danish National Patient RegisterScand J Public Health201139Suppl 7303321775347

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733833558716

- KieszakSMFlandersWDKosinskiASShippCCKarpHA comparison of the Charlson comorbidity index derived from medical record data and administrative billing dataJ Clin Epidemiol199952213714210201654

- PedersenCBThe Danish Civil Registration SystemScand J Public Health201139Suppl 7222521775345

- BrennerHRachetBHybrid analysis for up-to-date long-term survival rates in cancer registries with delayed recording of incident casesEur J Cancer200440162494250115519525

- AhernTPLashTLThwinSSSillimanRAImpact of acquired comorbidities on all-cause mortality rates among older breast cancer survivorsMed Care2009471737919106734

- ReadWLTierneyRMPageNCDifferential prognostic impact of comorbidityJ Clin Oncol200422153099310315284260

- De MarcoMFJanssen-HeijnenMLvan der HeijdenLHCoeberghJWComorbidity and colorectal cancer according to subsite and stage: a population-based studyEur J Cancer2000361959910741301

- AnandaSFieldKMKosmiderSPatient age and comorbidity are major determinants of adjuvant chemotherapy use for stage III colon cancer in routine clinical practiceJ Clin Oncol2008262745164517 author reply 451718802167

- van de Poll-FranseLVHaakHRCoeberghJWJanssen-HeijnenMLLemmensVEDisease-specific mortality among stage I-III colorectal cancer patients with diabetes: a large population-based analysisDiabetologia20125582163217222526616

- ColemanMPFormanDBryantHICBP Module 1 Working GroupCancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry dataLancet2011377976012713821183212

- KlintAEngholmGStormHHTrends in survival of patients diagnosed with cancer of the digestive organs in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006Acta Oncol201049557860720491524

- OstenfeldEBErichsenRIversenLHGandrupPNørgaardMJacobsenJSurvival of patients with colon and rectal cancer in central and northern Denmark, 1998–2009Clin Epidemiol20113Suppl 1273421814467

- IversenLHAspects of Survival from Colorectal Cancer in Denmark [Doctoral thesis]AarhusFaculty of Health Sciences, Aarhus University2011

- MacDermidEHootonGMacDonaldMImproving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary teamColorectal Dis200911329129518477019

- EhrensteinVAntonsenSPedersenLExisting data sources for clinical epidemiology: Aarhus University Prescription DatabaseClin Epidemiol20102273279

- de GrootVBeckermanHLankhorstGJBouterLMHow to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methodsJ Clin Epidemiol200356322122912725876

- ThygesenSKChristiansenCFChristensenSLashTLSørensenHTThe predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of PatientsBMC Med Res Methodol2011118321619668

- WeddingURöhrigBKlippsteinAPientkaLHöffkenKAge, severe comorbidity and functional impairment independently contribute to poor survival in cancer patientsJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol20071331294595017534661

- van SteenbergenLNElferinkMAKrijnenPWorking Group Output of The Netherlands Cancer RegistryImproved survival of colon cancer due to improved treatment and detection: a nationwide population-based study in The Netherlands 1989–2006Ann Oncol201021112206221220439339