Abstract

Gastric cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, the epidemiology of which has changed within last decades. A trend of steady decline in gastric cancer incidence rates is the effect of the increased standards of hygiene, conscious nutrition, and Helicobacter pylori eradication, which together constitute primary prevention. Avoidance of gastric cancer remains a priority. However, patients with higher risk should be screened for early detection and chemoprevention. Surgical resection enhanced by standardized lymphadenectomy remains the gold standard in gastric cancer therapy. This review briefly summarizes the most important aspects of gastric cancers, which include epidemiology, risk factors, classification, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. The paper is mostly addressed to physicians who are interested in updating the state of art concerning gastric carcinoma from easily accessible and credible source.

Epidemiology

Gastric carcinoma (GC) is the fourth most common malignancy worldwide (989,600 new cases per year in 2008) and remains the second cause of death (738,000 deaths annually) of all malignancies worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 The disease becomes symptomatic in an advanced stage. Five-year survival rate is relatively good only in Japan, where it reaches 90%.Citation3 In European countries, survival rates vary from ~10% to 30%.Citation4 High survival rate in Japan is probably achieved by early diagnosis by endoscopic examinations and consecutive early tumor resection.

The incidence shows wide geographical variation. More than 50% of the new cases occur in developing countries. There is a 15–20-fold variation in risk between the highest- and the lowest-risk populations. The high-risk areas are East Asia (China and Japan), Eastern Europe, Central and South America. The low-risk areas are Southern Asia, North and East Africa, North America, Australia, and New Zealand.Citation3

Steady declines in GC incidence rates have been observed worldwide in the last few decades.Citation3 This trend applies particularly to young patients with noncardia, sporadic, intestinal type of GC, as reported in the Japanese analysis.Citation5,Citation6 On the other hand, the American study differentiates race and age subpopulations, as well as the anatomic subtype of corpus gastric cancer, which have an increasing tendency.Citation7 Nevertheless, the general declining incidence of GC may be explained by higher standards of hygiene, improved food conservation, a high intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, and by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication.Citation8

Conclusions relating to the epidemiology

GC detected at the stage >T1N0 has a poor prognosis.

The incidence of GC varies geographically.

Within the last few decades, the incidence of GC has steadily declined.

Risk factors and prevention of gastric cancer

Gastric cancer results from a combination of environmental factors and accumulation of specific genetic alterations. Despite declining trends worldwide, prevention of GC should remain a priority. The primary prevention includes healthy diet, anti-H. pylori therapies, chemoprevention, and screening for early detection. Dietary factors have an important impact on gastric carcinogenesis, especially in case of intestinal adenocarcinoma. Healthy dietary habits, that is, high intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, Mediterranean diet, a low-sodium diet, salt-preserved food, red and high cured meat, sensible alcohol drinking, and maintaining a proper weight might be associated with a decreased risk of GC.Citation9–Citation11

The protective role of fresh fruits and dark green, light green, and yellow vegetables rich in B carotene, vitamin C, E, and foliate is strongly emphasized, probably due to their antioxidant effect. B carotene seems to be the leading risk reducer.Citation12

The beneficial influence of vitamin-rich diet seems to be particularly noticeable in case of earlier foliate and selenium deficiency.Citation13,Citation14

Nevertheless, the outcomes of various studies about anticancer properties of carotenoids, tocopherols, and retinoids are not always coherent. Therefore, the issue requires further investigations.Citation15

Many studies have confirmed that tobacco smoking increases the risk of GC, both cardia and noncardia subtypes.Citation16,Citation17 It has been shown that the risk of GC is increased by 60% in male and 20% in female smokers compared to nonsmokers. The risk of GC is lower in former smokers compared with occasional smokers, and smokers with higher consumption of cigarettes (>20 cigarettes per day) are at higher risk of GC.Citation16

Alcohol consumption also predisposes to GC.Citation18 The association between alcohol abuse and gastric cardia cancer was reported.Citation19

GC has been found to be inversely related to socioeconomic status, so that high socioeconomic position is associated with a reduced risk of GC, particularly cardia and intestinal subtypes.Citation20 Professions that are at higher risk of GC are minors, fishermen, machine operators, nurses, cooks, launderers, and dry cleaners as the main occupational exposures comprise dust, nitrogen oxides, N-nitroso compounds, and radiation.Citation21–Citation23

Marshal and Warren discovered the association between H. pylori and gastritis in 1982.Citation24 In 1994, H. pylori was classified as a class I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.Citation25 Next, it has been accused of being the main environmental factor causing GC.Citation26,Citation27 H. pylori infection is a common cause of gastrointestinal problems, but only a few infected patients develop a severe disease such as peptic ulcer (10%–15%) or GC (1%–3%).Citation28

In the general population, H. pylori infection reaches ~60%, but in patients with GC, it is more common (84%) or even inevitable (noncardia GC).Citation29,Citation30 The correlation between H. pylori infection and GC relates also to younger age (<40 years)Citation31 and is involved in both intestinal and diffuse types of noncardia GC. The latter is more common in early onset gastric cancer (EOGC).Citation32,Citation33

Undoubtedly, the strong correlation between H. pylori infection and GC is a possible target of intervention.Citation25 The Maastricht III Guidelines recommend to treat the infection in peptic ulcer diseases, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, atrophic gastritis, patients after resection of GC, first-degree relatives of GC patients, patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia, patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, patients who require long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and in patients who just wish to be treated.Citation34 The first-line eradication treatment of H. pylori relies on proton pump inhibitors and combination of two antibiotics such as amoxicillin, clarithromycin, or metronidazole. If the first therapy does not succeed, then the proposed second-line treatment is bismuth salts, proton pomp inhibitor, tetracycline, and metronidazole.Citation34

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a human herpes virus for which a causal role in gastric carcinogenesis has been suggested.Citation35 The association between EBV and carcinogenesis varies from 4% in China, 7.7% in France, 8.1% in Russia, 12.5% in Poland, to 17.9% in Germany.Citation36,Citation37 EBV in carcinoma biopsies indicates that the tumor has been formed by the proliferation of a single infected cell.Citation37 In addition, EBV infection might be a late event in gastric carcinogenesis.Citation38 Interestingly, EBV is more common in carcinomas in post-surgical gastric remnant (27%) than in an intact stomach.Citation39

Aspirin and NSAID users are shown to be at a reduced risk of GC.Citation40 On the other hand, the side effects of these are bleeding, perforation, or gastric outlet obstruction,Citation41 and therefore, these drugs are not recommended for patients with a history of digestive complaints.Citation42 In the late 1990s, there was an impermanent enthusiasm for the COX-2-selective NSAIDs, but shortly after, they were accused of increasing risk of myocardial infarction.Citation43

Familial clustering of GC has been reported for centuries and the world-famous example is the family of Napoleon Bonaparte.Citation44–Citation46 In 1998, truncating mutations of CDH1 were described in the germline of three New Zealand Maori families predisposed to diffuse GC.Citation45 In general, the risk of developing GC is calculated to be 1.5–3 fold increased in individuals with a family history of GC.Citation44

Obesity is a risk factor for gastric cardia carcinomas.Citation47 Less common risk factors include pernicious anemia, blood type A.Citation48,Citation49 Gastrectomy is also a risk factor for gastric cancer, a long time after partial gastrectomy.Citation50

Endoscopy is the most sensitive and specific diagnostic screening method.Citation51 However, mass screening for early detection of GC is expensive, and therefore, recommended only in regions with high incidence, such as East Asia, and senseless in low-incidence regions, such as North America.Citation52,Citation53

Additionally, endoscopic surveillance should be performed one to two times per year in patients who are at higher risk of GC (history of GC in family, familial adenomatous polyposis, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, BRCA2 mutations, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, and Ménétrier disease, previous gastric surgery, gastric polyps).Citation52,Citation54

Conclusions relating to risk factors and prevention

Early detection of both changeable and unchangeable GC risk factors is vital in primary prevention.

Changeable risk factors accounting for gastric cancer incidence are as follows:

Patient dependent: maintaining balanced diet, moderate alcohol intake, giving up smoking, and keeping normal weight.

Doctor dependent: H. pylori eradication, considering NSAIDs.

Unchangeable risk factors of GC are occupational exposures, family history of GC, comorbidities, and history of partial gastrectomy.

Classification of gastric cancer

Sporadic gastric cancer

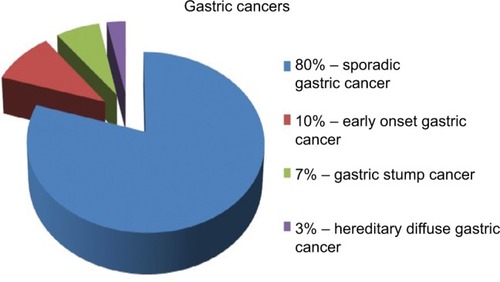

The majority of GC occurs sporadically and mainly affects people over the age of 45 years. These carcinomas are termed as “sporadic gastric cancers” (SGCs) ().Citation55 They are commonly caused by coincidence of many environmental factors.Citation56 They occur at the age of 60–80 years, and males are two times more often affected than females, particularly in high-risk countries.Citation57

Figure 1 Classification of gastric cancers.

Notes: Adapted from Skierucha M, Milne AN, Offerhaus GJ, Polkowski WP, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Molecular alterations in gastric cancer with special reference to the early-onset subtype. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(8):2460–2474. Copyright ©The Author(s) 2016. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.Citation55

Early onset gastric cancer

EOGC is defined as GC before the age of 45 years and encompasses about 10% of GCs ().Citation55,Citation58 In EOGCs, genetic factors seem to play the causal role.Citation56 These cancers are often multifocal, diffuse, and are more frequently observed in females, probably because of hormonal factors.Citation56,Citation59–Citation62 SGC and EOGC vary as well at the molecular level.Citation55,Citation63 Nevertheless, apart from the cases of hereditary GC, the pathogenesis of EOGC still remains unclear.

Gastric stump cancer

Gastric stump cancer (GSC) is a separate subtype of GC, defined as a carcinoma that occurs in the gastric remnant at least 5 years after the surgery for peptic ulcer.Citation64 GSC represents from 1.1% to 7% of all GCs (), and males are more prone to them than woman.Citation55,Citation65,Citation66 Gastrectomy is a well-established risk factor for GSC, even long time after the initial surgery.Citation50,Citation67 After 15 years from the gastrectomy, the risk of GSC is increased four- to sevenfold compared with the healthy population.Citation50,Citation68 EBV infection is more often in gastric remnants than in intact stomachs.Citation39 The virus may interact with the p53 protein.Citation69 In contrast, H. pylori infection in GSCs is less frequent.Citation70 GSCs are commonly preceded by well-defined precursor lesions, mostly by dysplasia, and therefore, endoscopic surveillance with multiple biopsies of the gastroenterostoma is recommended.Citation71

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC)

Most cases of GCs appear sporadically, but in 5%–10% of cases, familial clustering is observed.Citation44 HDGC concerns 1%–3% of all GCs ().Citation55,Citation72 HDGCs result from inherited syndromes, one of which are germline mutations in the CDH1 gene that encodes E-cadherin. These are autosomal dominant conditions that cause diffuse, poorly differentiated GC, which infiltrates into stomach wall and causes thickening of the wall without forming a distinct mass.

Conclusions related to classification

Eighty percent of GCs are SGCs. They occur mostly in elderly males, who come from high-risk area and have been exposed to environmental risk factors.

Ten percent of gastric cancers are EOGCs. They occur at the age <45 years, more frequently in females.

Seven percent of gastric cancers are GSCs. Most of them are preceded by dysplasia. The risk of them rises within time after gastrectomy.

Three percent of gastric cancers are HGDCs. They are inherited by autosomal dominant mutation of CDH1 gene.

Pathological classification

According to the World Health Organization guidelines, GC can be classified as adenocarcinoma, signet ring-cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma. However, it is not as widely used as the Lauren classification, which distinguishes two major subtypes of GC, intestinal and diffuse types.Citation73 The Lauren classification contains microscopic and macroscopic differences.Citation73 It has been postulated that intestinal types of GC are associated with chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, whereas diffuse types originate from normal gastric mucosa. The ratio of intestinal and diffuse types varies between countries and continents. In European countries, intestinal type is currently more common.Citation74–Citation78 It tends to occur more often in the distal stomach, in high-risk areas, and it is often preceded by a long-standing precancerous lesion.Citation75 The diffuse type prevails among young patients. The extent of the surgical resection depends on the Lauren’s histological subtype of GCs.

Conclusions relating to the pathological classification

GC is mostly divided into two subtypes: intestinal and diffuse ones.

Extent of surgical resection depends on histopathological outcome.

Treatment

Multidisciplinary approach for the planning of the GC treatment is mandatory. The multidisciplinary team (MDT) should include at least a surgeon, pathologist, gastroenterologist, medical and radiation oncologists.Citation79 In case of curative intention, the surgery involves complete resection with a standardized D2 lymphadenectomy.Citation80 In 1998, Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) standardized the regional lymphadenectomy based on the location of the tumor and the respective regional node drainage. Sixteen different lymph node stations around the stomach have been recognized. The lymph node stations along the lesser curvature (stations 1, 3, and 5) and the greater curvature (stations 2, 4, and 6) of the stomach have been grouped as N1. The nodes along the left gastric artery (station 7), the common hepatic artery (station 8), the celiac artery (station 9), and the splenic artery (stations 10 and 11) have been grouped as N2. N3 group has encompassed the lymph nodes along the hepatoduodenal ligament (station 12), at the posterior site of the pancreas (station 13), and at the root of the mesentery (station 14). Finally, the lymph nodes around the middle colic artery (station 15) and lower paraesophageal lymph node and diaphragmatic lymph (station 16) have been grouped as N4.Citation81 D1, D2, and D3 are the names given to the procedures that depend on the range of lymphadenectomy.Citation81 However, the seventh edition of TNM classification and a new version of the JGCA classification cancer of the stomach changed the definitions of D1/D2 lymphadenectomy according to the extent of gastric resection ().Citation82 Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) in early GC treatment (T1aN0M0) and in intraepithelial neoplasia can provide the same effect as traditional surgical resection.Citation83,Citation84 For well-differentiated types of mucosal tumors, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is often successful.Citation84,Citation85 Splenectomy is acceptable only in the case of the direct cancer infiltration of the splenic hilum.Citation86 Advanced gastric tumors with distant metastasis are usually incurable; however, it does not concern cases with solitary liver metastasis or peritoneal nodules invasion. For incurable GC patients, palliative resection may improve the quality of life, but it is not recommended in an asymptomatic patients.Citation87 Histological examination after regional lymphadenectomy should include more than 15 lymph nodes. Treatment recommendations of the JGCA (fourth edition from 2014) are presented in .Citation82

Table 1 Extent of lymphadenectomy according to the type of gastric resection

Table 2 The JGCA cancer classification according to the extent of gastric resection and D1/D2 lymphadenectomy.

The high incidence of distant metastases and the local recurrence after have paved the way for systemic therapy, and recently in neo-adjuvant therapy.Citation88 The extensive treatment may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy or immunotherapy, either alone or in combinations. Adjuvant therapy has been shown to be beneficial in GC.Citation89,Citation90 Recent studies have revealed the superiority of the neoadjuvant therapy combined with surgery over the surgery alone, with 5-years progression-free rate at 23%–36%.Citation91 Palliative chemotherapy or surgery is recommended in patients with metastases, but in a good general condition. In case of patients with poor performance status, the supportive treatment is the only recommendation.Citation86 Management algorithm for patients in a good general condition without distant metastases (M0) is shown in .Citation92

Figure 2 Management algorithm for patients in good performance status and without distant metastases (M0).

Notes: Modified with permission from Polkowski W, Łacko A, Guzel Z. Nowotwory żołądka [Gastric cancers]. In: Krzakowski M, Warzecha K, editors. Zalecenia postępowania diagnostyczno-terapeutycznego w nowotworach złośliwych – 2013 rok [Recommendations for Diagnostics and Treatment of Malignant Neoplasms – 2013]. Gdansk: Via Medica; 2013:119. Copyright © 2013 Via Medica.Citation92

Abbreviations: EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

![Figure 2 Management algorithm for patients in good performance status and without distant metastases (M0).Notes: Modified with permission from Polkowski W, Łacko A, Guzel Z. Nowotwory żołądka [Gastric cancers]. In: Krzakowski M, Warzecha K, editors. Zalecenia postępowania diagnostyczno-terapeutycznego w nowotworach złośliwych – 2013 rok [Recommendations for Diagnostics and Treatment of Malignant Neoplasms – 2013]. Gdansk: Via Medica; 2013:119. Copyright © 2013 Via Medica.Citation92Abbreviations: EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; MDT, multidisciplinary team.](/cms/asset/e2062840-297e-4d7e-9914-26b3b637c085/dcmr_a_12185331_f0002_c.jpg)

Chemotherapy

Two randomized trials have shown an improvement in overall survival in patients receiving perioperative chemotherapy.Citation91,Citation93 Such a treatment is, therefore, routinely performed in Europe and includes three cycles of chemotherapy before surgery and three cycles after surgery.Citation94

Neo-adjuvant (chemo-)radiotherapy

The results of the INT 0116 trial have shown the effectiveness of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy compared with surgery alone. Three-year observation has shown an 11% improvement in overall survival after combined treatment, with a median survival of 36 months. It has been compared with only 27 months of survival after surgery alone. The median recurrence-free survival time has been 30 months in the chemo-radiotherapy group and 19 months in the surgery alone group.Citation95

Although adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is recommended in the United States, in the European countries, the treatment has been limited to cases with suboptimal lymphadenectomy (removal of <15 lymph nodes) or irradical microscopic resection (R1) of the stomach.Citation96 Application of adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy after D1 lymphadenectomy reduces the incidence of local recurrence and improves survival of the patients.Citation97,Citation98

The results of perioperative chemotherapy in patients with GC and gastro-esophageal junction are promising.Citation91,Citation93 A statistically significant improvement of overall survival and progression-free survival has been observed in 36% of patients with perioperative chemotherapy compared with 23% after the operation alone.Citation91 Therefore, perioperative chemotherapy plus radical surgery has been recommended as a standard treatment for locally advanced tumors.Citation99,Citation100

Combination of regiments bases traditionally upon a platinum– fluoropyrimidine doublet, but adding an anthracycline has been shown to be beneficial.Citation101 The most commonly used protocols are ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU), ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine), EOF (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, 5-FU), and EOX (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine). Alternatively, chemonaive patients might be treated with taxane-based or irinotecan/5-fluorouracil regiments.Citation94,Citation102

Second-line therapy bases on irinotecan, docetaxel, and paclitaxel.Citation103–Citation106 However, in case of late disease progression after first-line chemotherapy (after >3 months), it might be beneficial to try the same drugs again.Citation94

Despite the improvement in overall survival after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, high occurrence of relapses are still observed. Therefore, addition of radiotherapy in preoperative setting may be beneficial. Radiotherapy is well tolerated, improves the resectability of the tumor, and does not increase the frequency of surgical complications. Currently, adjuvant radio-chemotherapy is recommended in patients with loco-regionally advanced carcinoma of the gastro-esophageal junction (T2N1-3M0 or T3N0-3M0).Citation107

Palliative radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is justified in cases of unresectable GC with anemia, and/or in the cases with pyloric or cardiac obstruction. The dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions can be effective both in diminishing bleeding and in improving the food passage. The effect is usually short (3–6 months), but it is an easy therapeutic option.Citation108,Citation109

Treatment of gastric cancer in the metastatic setting

Compared with symptomatic treatment, palliative chemotherapy for patients with inoperable GC prolongs survival and improves its quality. In 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration approved “trastuzumab”, a monoclonal antibody that interferes with the HER2 receptor, for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic GC. Following the results of the ToGA trial, “trastuzumab” in combination with capecitabine or 5-FU and cisplatin is now the standard of care for HER2-positive GCs.Citation82,Citation110

Second-line chemotherapies base on the regimens with a taxane (docetaxel, paclitaxel), or irinotecan, or ramucirumab as single agent or in combination with paclitaxel. Ramucirumab is the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 monoclonal antibody that has been associated with a survival benefit compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy in the second-line setting. Ramucirumab in addition to paclitaxel has correlated with a survival benefit compared with paclitaxel alone.Citation82,Citation111,Citation112

However, chemotherapy may be used only in patients with good performance status (PS 0–1).Citation82 Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival in a group of highly selected patients with limited peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin (peritoneal cancer index <12).Citation113,Citation114

Conclusions relating to treatment

Operation range depends on the stage of the disease, and it is described in recommendations from 2010 ().

Systematic therapy improves long-term, progression-free survival rate in comparison with surgical treatment alone.

Palliative chemotherapy in patients with inoperable gastric cancer prolongs survival and improves the quality of life.

Conclusion

GC is a malignant disease with a generally poor long-term prognosis. The majority of GCs are sporadic subtypes that are strongly associated with environmental risk factors. In the last decades, some mechanisms of gastric cancerogenesis have been elucidated, which has resulted in the primary and secondary prevention, such as healthy lifestyle and H. pylori eradication. Consequently, the incidence of gastric cancer has started to decline. This tendency does not concern the GC subtypes that result from genetic predisposition or comorbidities. Nevertheless, the endoscopic surveillance program is recommended for screening a group of patients with the highest risk of GC.

Every patient with GC needs to be treated according to the individual plan made by MDT. The planning strategy should consider: stage of the tumor, intention of the therapy, patient’s performance status, and technical possibilities. Generally, the most beneficial approach seems to be surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WrightNAPoulsomRStampGTrefoil peptide gene expression in gastrointestinal epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel diseaseGastroenterology1993104112208419234

- JemalABrayFCenterMMFerlayJWardEFormanDGlobal cancer statisticsCA Cancer J Clin2011612699021296855

- StockMOttoFGene deregulation in gastric cancerGene2005360111916154715

- ParkinDMBrayFFerlayJPisaniPGlobal cancer statistics 2002CA Cancer J Clin20055527410815761078

- KanekoSYoshimuraTTime trend analysis of gastric cancer incidence in Japan by histological types, 1975–1989Br J Cancer200184340040511161407

- BertuccioPChatenoudLLeviFRecent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overviewInt J Cancer2009125366667319382179

- CamargoMCAndersonWFKingJBDivergent trends for gastric cancer incidence by anatomical subsite in US adultsGut201160121644164921613644

- MunozNFranceschiSEpidemiology of gastric cancer and perspectives for preventionSalud Publica Mex19973943183309337564

- BucklandGTravierNHuertaJMHealthy lifestyle index and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in the EPIC cohort studyInt J Cancer2015137359860625557932

- LinSHLiYHLeungKHuangCYWangXRSalt processed food and gastric cancer in a Chinese populationAsian Pac J Cancer Prev201415135293529825040991

- MassarratSStolteMDevelopment of gastric cancer and its preventionArch Iran Med201417751452024979566

- NomuraAMHankinJHKolonelLNWilkensLRGoodmanMTStemmermannGNCase-control study of diet and other risk factors for gastric cancer in Hawaii (United States)Cancer Causes Control200314654755812948286

- TavaniAMalerbaSPelucchiCDietary folates and cancer risk in a network of case-control studiesAnn Oncol201223102737274222898036

- CamargoMCBurkRFBravoLEPlasma selenium measurements in subjects from areas with contrasting gastric cancer risks in ColombiaArch Med Res200839444345118375257

- JenabMRiboliEFerrariPPlasma and dietary carotenoid, retinol and tocopherol levels and the risk of gastric adenocarcinomas in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutritionBr J Cancer200695340641516832408

- Ladeiras-LopesRPereiraAKNogueiraASmoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studiesCancer Causes Control200819768970118293090

- NishinoYInoueMTsujiIResearch Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in JapanTobacco smoking and gastric cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese populationJpn J Clin Oncol2006361280080717210611

- JedrychowskiWWahrendorfJPopielaTRachtanJA case-control study of dietary factors and stomach cancer risk in PolandInt J Cancer19863768378423710615

- LagergrenJBergströmRLindgrenANyrénOThe role of tobacco, snuff and alcohol use in the aetiology of cancer of the oesophagus and gastric cardiaInt J Cancer200085334034610652424

- NagelGLinseisenJBoshuizenHCSocioeconomic position and the risk of gastric and oesophageal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST)Int J Epidemiol2007361667617227779

- CoccoPPalliDBuiattiEOccupational exposures as risk factors for gastric cancer in ItalyCancer Causes Control1994532412488061172

- SimpsonJRomanELawGPannettBWomen’s occupation and cancer: preliminary analysis of cancer registrations in England and Wales, 1971–1990Am J Ind Med199936117218510361604

- AragonesNPollanMGustavssonPStomach cancer and occupation in Sweden: 1971–89Occup Environ Med200259532933711983848

- WarrenJRMarshallBUnidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritisLancet198318336127312756134060

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to HumansLyon, 7–14 June 1994. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pyloriIARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum19946112417715068

- FormanDNewellDGFullertonFAssociation between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigationBMJ19913026788130213052059685

- ParsonnetJSamloffIMNelsonLMOrentreichNVogelmanJHFriedmanGDHelicobacter pylori, pepsinogen, and risk for gastric adenocarcinomaCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev1993254614668220091

- SuerbaumSMichettiPHelicobacter pylori infectionN Engl J Med2002347151175118612374879

- ParsonnetJFriedmanGDVandersteenDPHelicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinomaN Engl J Med199132516112711311891020

- GonzálezCAMegraudFBuissonniereAHelicobacter pylori infection assessed by ELISA and by immunoblot and noncardia gastric cancer risk in a prospective study: the Eurgast-EPIC projectAnn Oncol20122351320132421917738

- MasudaGTokunagaAShirakawaTHelicobacter pylori infection, but not genetic polymorphism of CYP2E1, is highly prevalent in gastric cancer patients younger than 40 yearsGastric Cancer20071029810317577619

- CorreaPHoughtonJCarcinogenesis of Helicobacter pyloriGastroenterology2007133265967217681184

- RuggeMBusattoGCassaroMPatients younger than 40 years with gastric carcinoma: Helicobacter pylori genotype and associated gastritis phenotypeCancer199985122506251110375095

- MalfertheinerPMegraudFO’MorainCCurrent concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus ReportGut200756677278117170018

- ImaiSKoizumiSSugiuraMGastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein-Barr virus latent infection proteinProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19949119913191358090780

- CzopekJPStojakMSińczakAEBV-positive gastric carcinomas in PolandPol J Pathol200354212312814575421

- TakadaKEpstein-Barr virus and gastric carcinomaMol Pathol200053525526111091849

- Zur HausenAvan ReesBPvan BeekJEpstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinomas and gastric stump carcinomas: a late event in gastric carcinogenesisJ Clin Pathol200457548749115113855

- YamamotoNTokunagaMUemuraYEpstein-Barr virus and gastric remnant cancerCancer19947438058098039108

- WangWHHuangJQZhengGFLamSKKarlbergJWongBCNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Natl Cancer Inst200395231784179114652240

- HarbisonSPDempseyDTPeptic ulcer diseaseCurr Probl Surg200542634645415988415

- FarrowDCVaughanTLHanstenPDUse of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancerCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev199872971029488582

- BombardierCLaineLReicinAVIGOR Study GroupComparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study GroupN Engl J Med2000343211520152811087881

- La VecchiaCNegriEFranceschiSGentileAFamily history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancerCancer199270150551606546

- GuilfordPHopkinsJHarrawayJE-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancerNature199839266744024059537325

- SokoloffBPredisposition to cancer in the Bonaparte familyAm J Surg1938403673678

- VaughanTLDavisSKristalAThomasDBObesity, alcohol, and tobacco as risk factors for cancers of the esophagus and gastric cardia: adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinomaCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev19954285927742727

- HsingAWHanssonLEMcLaughlinJKPernicious anemia and subsequent cancer. A population-based cohort studyCancer19937137457508431855

- AirdIBentallHHRobertsJAA relationship between cancer of stomach and the ABO blood groupsBr Med J19531481479980113032504

- OfferhausGJTersmetteACHuibregtseKMortality caused by stomach cancer after remote partial gastrectomy for benign conditions: 40 years of follow up of an Amsterdam cohort of 2633 postgastrectomy patientsGut19882911158815903209117

- TashiroASanoMKinameriKFujitaKTakeuchiYComparing mass screening techniques for gastric cancer in JapanWorld J Gastroenterol200612304873487416937471

- LeungWKWuMSKakugawaYScreening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practiceLancet Oncol20089327928718308253

- DickenBJBigamDLCassCMackeyJRJoyAAHamiltonSMGastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directionsAnn Surg20052411273915621988

- HirotaWKZuckermanMJAdlerDGStandards of Practice Committee, American Society for Gastrointestinal EndoscopyASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of pre-malignant conditions of the upper GI tractGastrointest Endosc200663457058016564854

- SkieruchaMMilneANOfferhausGJPolkowskiWPMaciejewskiRSitarzRMolecular alterations in gastric cancer with special reference to the early-onset subtypeWorld J Gastroenterol20162282460247426937134

- KikuchiSNakajimaTNishiTAssociation between family history and gastric carcinoma among young adultsJpn J Cancer Res19968743323368641962

- FormanDBurleyVJGastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factorsBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200620463364916997150

- KokkolaASipponenPGastric carcinoma in young adultsHepatogastroenterology200148421552155511813570

- HaydenJDCawkwellLSue-LingHAssessment of microsatellite alterations in young patients with gastric adenocarcinomaCancer19977946846879024705

- LimSLeeHSKimHSKimYIKimWHAlteration of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion protein is common, but microsatellite instability is uncommon in young age gastric cancersHistopathology200342212813612558744

- Ramos-De la MedinaASalgado-NesmeNTorres-VillalobosGMedina-FrancoHClinicopathologic characteristics of gastric cancer in a young patient populationJ Gastrointest Surg20048324024415019915

- MaetaMYamashiroHOkaATsujitaniSIkeguchiMKaibaraNGastric cancer in the young, with special reference to 14 pregnancy-associated cases: analysis based on 2,325 consecutive cases of gastric cancerJ Surg Oncol19955831911957898116

- MilneANCarvalhoRMorsinkFMEarly-onset gastric cancers have a different molecular expression profile than conventional gastric cancersMod Pathol200619456457216474375

- ThorbanSBöttcherKEtterMRoderJDBuschRSiewertJRPrognostic factors in gastric stump carcinomaAnn Surg2000231218819410674609

- SonsHUBorchardFGastric carcinoma after surgical treatment for benign ulcer disease: some pathologic-anatomic aspectsInt Surg19877242222263448034

- SinningCSchaeferNStandopJHirnerAWolffMGastric stump carcinoma – epidemiology and current concepts in pathogenesis and treatmentEur J Surg Oncol200733213313917071041

- ToftgaardCGastric cancer after peptic ulcer surgery. A historic prospective cohort investigationAnn Surg198921021591642757419

- TersmetteACGoodmanSNOfferhausGJMultivariate analysis of the risk of stomach cancer after ulcer surgery in an Amsterdam cohort of postgastrectomy patientsAm J Epidemiol1991134114211853856

- van ReesBPCaspersEzur HausenADifferent pattern of allelic loss in Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer with emphasis on the p53 tumor suppressor pathwayAm J Pathol200216141207121312368194

- BaasIOvan ReesBPMuslerAHelicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus infection and the p53 tumour suppressor pathway in gastric stump cancer compared with carcinoma in the non-operated stomachJ Clin Pathol19985196626669930069

- OfferhausGJvan de StadtJHuibregtseKTersmetteACTytgatGNThe mucosa of the gastric remnant harboring malignancy. Histologic findings in the biopsy specimens of 504 asymptomatic patients 15 to 46 years after partial gastrectomy with emphasis on nonmalignant lesionsCancer19896436987032743264

- PalliDGalliMCaporasoNEFamily history and risk of stomach cancer in ItalyCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev19943115188118379

- LaurenPThe two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classificationActa Pathol Microbiol Scand196564314914320675

- QiuMZCaiMYZhangDSClinicopathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of Lauren classification in gastric adenocarcinoma in ChinaJ Transl Med2013115823497313

- AhnHSLeeHJHahnSEvaluation of the seventh American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Classification of gastric adenocarcinoma in comparison with the sixth classificationCancer2010116245592559820737569

- LaurenPANevalainenTJEpidemiology of intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma. A time-trend study in Finland with comparison between studies from high- and low-risk areasCancer19937110292629338490820

- RibeiroMMSarmentoJASobrinho SimõesMABastosJPrognostic significance of Lauren and Ming classifications and other pathologic parameters in gastric carcinomaCancer19814747807847226025

- AmorosiABianchiSBuiattiECiprianiFPalliDZampiGGastric cancer in a high-risk area in Italy. Histopathologic patterns according to Lauren’s classificationCancer19886210219121963179931

- SitarzRKocembaKMaciejewskiRPolkowskiPEffective cancer treatment by multidisciplinary teamsPol Przegl Chir201284737137622935461

- UshijimaTSasakoMFocus on gastric cancerCancer Cell20045212112514998488

- KajitaniTThe general rules for the gastric cancer study in surgery and pathology. Part I. Clinical classificationJpn J Surg19811121271397300058

- Japanese Gastric Cancer AssociationJapanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4)Gastric Cancer2017201119

- OnoHKondoHGotodaTEndoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancerGut200148222522911156645

- GotodaTEndoscopic resection of early gastric cancerGastric Cancer200710111117334711

- GotodaTYanagisawaASasakoMIncidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centersGastric Cancer20003421922511984739

- OkinesAVerheijMAllumWGastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201021Suppl 5S50S54

- ScheidbachHLippertHMeyerFGastric carcinoma: when is palliative gastrectomy justified?Oncol Rev201042127132

- D’AngelicaMGonenMBrennanMFTurnbullADBainsMKarpehMSPatterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinomaAnn Surg2004240580881615492562

- JanungerKGHafströmLNygrenPGlimeliusBSBU-groupSwedish Council of Technology Assessment in Health Care. A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in gastric cancerActa Oncol2001402–330932611441938

- EarleCCMarounJZurawLCancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site GroupNeoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy for resectable gastric cancer? A practice guidelineCan J Surg200245643844612500920

- CunninghamDAllumWHStenningSPMAGIC Trial ParticipantsPerioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancerN Engl J Med20063551112016822992

- PolkowskiWŁackoAGuzelZNowotwory żołądka [Gastric cancers]KrzakowskiMWarzechaKZalecenia postępowania diagnostyczno-terapeutycznego w nowotworach złośliwych – 2013 rok [Recommendations for Diagnostics and Treatment of Malignant Neoplasms – 2013]GdanskVia Medica2013119

- YchouMBoigeVPignonJPPerioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trialJ Clin Oncol201129131715172121444866

- WaddellTVerheijMAllumWGastric cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201324Suppl 6S57S63

- MacdonaldJSSmalleySRBenedettiJChemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junctionN Engl J Med20013451072573011547741

- SmalleySRGundersonLTepperJGastric surgical adjuvant radiotherapy consensus report: rationale and treatment implementationInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200252228329311872272

- DikkenJLJansenEPCatsAImpact of the extent of surgery and postoperative chemoradiotherapy on recurrence patterns in gastric cancerJ Clin Oncol201028142430243620368551

- Van CutsemEVan de VeldeCRothAEuropean Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-gastrointestinal cancer groupExpert opinion on management of gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma on behalf of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-gastrointestinal cancer groupEur J Cancer200844218219418093827

- WilkeHStahlMTherapie beim Magenkarzinom. Aus onkologischer Sicht [Therapy in gastric cancer. From an oncological perspective]Chirurg2009801110231027 German19902288

- OttKLordickFNeoadjuvant therapy in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastric cancer from a surgical viewpointChirurg2009801110281034 German19756431

- WagnerADUnverzagtSGrotheWChemotherapy for advanced gastric cancerCochrane Database Syst Rev20103CD004064

- DankMZaluskiJBaroneCRandomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junctionAnn Oncol20081981450145718558665

- Thuss-PatiencePCKretzschmarABichevDSurvival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemein-schaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO)Eur J Cancer201147152306231421742485

- KangJHLeeSILimDHSalvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care aloneJ Clin Oncol201230131513151822412140

- FordHEMarshallABridgewaterJADocetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trialLancet Oncol2014151788624332238

- RoyACParkSRCunninghamDA randomized phase II study of PEP02 (MM-398), irinotecan or docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinomaAnn Oncol20132461567157323406728

- MatzingerOGerberEBernsteinZEORTC-ROG expert opinion: radiotherapy volume and treatment guidelines for neoadjuvant radiation of adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction and the stomachRadiother Oncol200992216417519375186

- TeyJBackMFShakespeareTPThe role of palliative radiation therapy in symptomatic locally advanced gastric cancerInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200767238538817118569

- AsakuraHHashimotoTHaradaHPalliative radiotherapy for bleeding from advanced gastric cancer: is a schedule of 30 Gy in 10 fractions adequate?J Cancer Res Clin Oncol2011137112513020336314

- BangYJVan CutsemEFeyereislovaAToGA Trial InvestigatorsTrastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trialLancet2010376974268769720728210

- WilkeHMuroKVan CutsemERamucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trialLancet Oncol201415111224123525240821

- FuchsCSTomasekJYongCJREGARD Trial InvestigatorsRamucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trialLancet20143839911313924094768

- YangXJHuangCQSuoTCytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trialAnn Surg Oncol20111861575158121431408

- GlehenOGillyFNArvieuxCPeritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: a multi-institutional study of 159 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapyAnn Surg Oncol20101792370237720336386