Abstract

Biopharmaceuticals (biologics) represent one of the fastest growing sectors of cancer treatment. They are recommended for treating underlying cancer and as supportive care for management of treatment side effects. Given the high costs of cancer care and the need to balance health care provision and associated budgets, patient access and value are the subject of discussion and debate in the USA and globally. As the costs of biologics are high, biosimilars offer the potential of greater choice and value, increased patient access to treatment, and the potential for improved outcomes. Value-based care aims to improve the quality of care, while containing costs. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed value-based care programs as alternatives to fee-for-service reimbursement, including in oncology, that reward health care providers with incentive payments for improving the quality of care they provide. It is anticipated that CMS payments in oncology care will be increasingly tied to measured performance. This review provides an overview of value-based care models in oncology with a focus on CMS programs and discusses the contribution of biosimilars to CMS value-based care objectives. Biosimilars may provide an important tool for providers participating in value-based care initiatives, resulting in cost savings and efficiencies in the delivery of high-value care through expanded use of biologic treatment and supportive care agents during episodes of cancer care.

Introduction

As of the early 1980s, biopharmaceuticals represent one of the fastest growing sectors of the drug industry worldwideCitation1 and are increasingly important in cancer care. Biologics (e.g., monoclonal antibodies [mAbs] and hematopoietic agents)Citation2 are recommended in oncology guidelinesCitation3 for treating underlying disease as well as for managing treatment side effects through supportive care agents such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSFs) and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).Citation4

Biologics are produced from cells of living organisms and purified in complex, multi-step processes, including recombinant DNA technology, controlled gene expression, or antibody technologies.Citation2 Compared with chemically synthesized small molecule drugs, biologics have 100- to 1000-fold larger molecular weight and are relatively heterogeneousCitation5; their physiochemical structure is complex and difficult to characterize. Furthermore, they are highly sensitive to changes in manufacturing conditions, and as a result, no two biological products can be identical,Citation6 resulting in a complex production process. Biologic agents, including those used in cancer treatment and supportive care, have improved outcomes for patients, who often require ongoing treatment. As costs of biologics are high, long-term treatment of patients with biologics can be a chronic burden to health care systems.Citation7

Biosimilars of reference biologic agents offer an alternative choice and value that has potential to open further patient access to treatment and associated outcomes. According to the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) definition, a biosimilar is a biologic product that is highly similar to an already licensed reference biologic that has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency.Citation8,Citation9 Biosimilars remain fairly new to the US market, particularly in the oncology space; however, this is anticipated to change rapidly with multiple biosimilar entrants expected in oncological treatment and supportive care in the upcoming years.Citation10

Given the disproportionate burden of cancer in the elderly, understanding the intersection of the availability of biosimilars and the growing interest in value-based oncology care models, particularly within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), is of increasing importance in health care delivery.

The objective of this review is to provide an overview of value-based care models in oncology with a focus on the CMS programs and to discuss the potential contribution of biosimilars to CMS value-based care objectives. This review first describes the use of biologics in targeted and supportive oncology care, introduces biosimilars, and then examines the historical legacy and objectives of the CMS value programs with a focus on how biosimilars might support broader access to equitable, high-quality oncology care.

The high cost of cancer care

The increased prevalence of cancers, earlier treatment initiation, and improved patient outcomes all contribute to the growing use of oncology and supportive care biologic agents. These factors, coupled with the high costs of manufacturing biologics and macro- and micro-economic factors resulting in higher health care costs, have led to a rise in cancer care spending.Citation7,Citation11 In high-income countries, the costs of delivering cancer care are outstripping national budgets, and sustainability of health care financing remains a key public policy concern.Citation12

Biologics in cancer treatment and supportive care

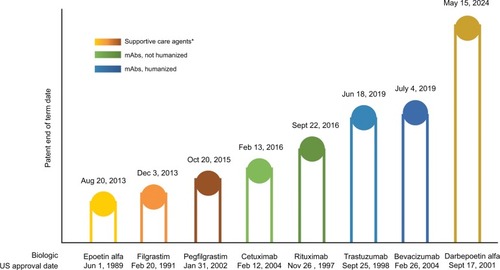

Biologics have been approved for use in primary cancer treatment and supportive care since 1989 (). Primary treatment biologics include, but are not limited to, cetuximab,Citation13 rituximabCitation14 (chimeric mAbs targeting epidermal growth factor receptor and CD20, respectively), trastuzumab,Citation15 and bevacizumabCitation16 (humanized mAbs that inhibit human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor A, respectively). These biologics have been shown to improve clinical, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and hematological outcomes.Citation13,Citation17 Biologics are not exclusive to primary treatment, but they have been developed for supportive oncologic treatment as well. Supportive oncologic treatment addresses the adverse effects that are common with primary chemotherapy. Biologics in supportive oncology care include, but are not limited to, agents that help replenish hematologic components during and following chemotherapy. Epoetin alfa and darbepoetin are recombinant human erythropoietic proteins. Filgrastim and its analog, pegfilgrastim, are recombinant human G-CSF. The use of supportive care biologics with chemotherapy improves hematological responseCitation18–Citation22 and has a positive effect on HRQoL.Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23

Figure 1 US patent end of term dates for oncology mAbs and supportive care drugs.

Notes: *Biologic growth factors for the treatment of anemia or neutropenia due to myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Data from Generics and Biosimilars InitiativeCitation61 and Micklus.Citation103

Abbreviation: mAbs, monoclonal antibodies.

Biologic therapies have improved treatment outcomes over previous standard-of-care chemotherapy, while biologic supportive care agents have been shown to be associated with reduced treatment side effects resulting in improved patient-reported HRQoL.Citation13,Citation17,Citation22 However, patient access to biologics may be limited by availability, insurance coverage, and cost. As many available biologics reach the end of their patent protection periods (US patents for cetuximab expired in 2014, for ritxuimab in 2016, and for both trastuzmumab and bevacizuamb, they will reach the end of term in 2019Citation24), patient access has become an important consideration among the balance of high-quality care and costs. Within the context of this balance, biosimilars are being developed as alternative options with potentially lower costs and greater access. By 2020, a range of biosimilars of biologic agents used in oncology treatment are expected to receive US FDA approval and become available in the US market, providing increased treatment options and thus competition, with the potential for pricing reductions.

Costs of biologics cancer care in the USA

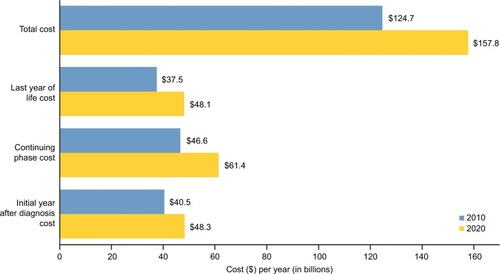

In the USA, total spending on cancer care has increased from $27 billion in 1990 to $124 billion in 2010, with spending projected to reach around $157 billion by 2020.Citation25,Citation26 Total costs of cancer care for the US population are predicted to increase across all phases of care ().Citation27 Cost drivers include technological innovation, rising costs of hospitalizations, and a population-level increasing susceptibility to malignancy due to an aging demographic and increasing life span.Citation28 Global spending on oncology and supportive care drugs reached $100 billion in 2014, with targeted therapy expenditures accounting for almost 50% of this amount.Citation11 In the USA, oncology drug expenditures, excluding supportive care agents, increased by 18.0% from 2014 to 2015.Citation29 The fastest growing drug classes within oncology are mAbs and protein-kinase inhibitors, with mAbs accounting for 35% of US oncology spending.Citation29 US sales figures in 2015 for three of the top 20 global products – bevacizumab, rituximab and trastuzumab – were $6.2 billion, $6.3 billion, and $5.6 billion, respectively.Citation30 US patients are shouldering an increasing share of these rising costs as health plans restructure their benefit designs, including a transition to high-deductible health plans with higher patient out-of-pocket costs from traditional fixed copay plans.Citation28 The financial consequences of cancer treatment on patients and their families can be substantial,Citation31,Citation32 which has been shown to be a substantial burden.Citation33,Citation34 Given the high costs of cancer care and the need to balance health care provision and associated budgets for the full range of conditions affecting population health, issues of patient access, value, and equity are the subject of global discussion and debate.

Figure 2 Current and projected cost of cancer care in the USA by phase of care in 2010 and 2020, respectively, weighted to dollar values in 2010.

Note: Data from National Cancer Institute.Citation27

Oncology biosimilars in Europe

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) first introduced a regulatory framework for biosimilars in 2004, and by 2006, it had established a comprehensive set of guidelines for their approval.Citation35 Since then, European countries have approved the highest number of biosimilars worldwide, having shown high similarity to their reference products via a series of studies (efficacy and safety), and on the basis of nonclinical and pharmaceutical quality data.Citation35,Citation36 For example, in the European Union, clinical guidelines were updated in 2009 to encourage the use of biosimilar filgrastim, which led to significantly increased consumption, enabling greater numbers of patients access to this treatment at earlier stages of the therapy cycle.Citation37

Approvals for supportive oncology care biosimilars in Europe have been ongoing. As of January 2018, nine filgrastim and five epoetin alfa/zeta biosimilar products were approvedCitation38 and have had tremendous impact on improving access to treatment.Citation39,Citation40 As of this publication, license applications for three pegfilgrastim biosimilars were under review by the EMA. For targeted therapies, five rituximab biosimilars, all licensed for the same or similar oncology indications,Citation38 are authorized by the EMA, and five trastuzumab biosimilars are still under review.Citation41

Biosimilars provide an opportunity for cost savings. In Europe, individual member states are allowed to negotiate their own pricing on biosimilars.Citation24,Citation42 According to a 2016 IMS report,Citation37 the observed price reduction for epoetins (in 2015) following the introduction of biosimilar competition varied substantially among countries: 25%–29% in Scandinavia; 39% in France; and 55% in Germany. Meanwhile, the observed price change (in 2015) for biologic and biosimilar filgrastim, following the launch of the first approved filgrastim biosimilar, varied from 14% in France to 27% in Germany, based on gross ex-manufacturer price.Citation37 A significant increase in consumption of therapeutic biologics and biosimilars has been shown in European countries upon entry of a biosimilar into the marketCitation43 and this increase is attributed to reduced costs.Citation44,Citation45 It should be noted, however, that owing to substantial international differences in market forces, drug pricing, and health care policy (as well as in access and utilization), European pricing data are not applicable to the US market.Citation46

Biosimilar use in other regions

Biosimilars are used widely in the Middle EastCitation47 and in Asia.Citation48 Reasons for use include lower price relative to reference biologics and bioequivalence of efficacy and safety.Citation47 Regulatory approvals, where needed, are largely modeled after US FDA and EMA guidelines.Citation48

Biosimilars in cancer treatment and supportive care in the USA

The USA has a regulatory framework for biosimilars, which was enacted as the 2009 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act,Citation49 part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. This created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products demonstrated to be biosimi-lar to, or interchangeable with, a US FDA-licensed biological product (or “reference product”), known as the 351(k) pathway.Citation8 The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the sales-weighted market average discount on biosimilars would be 20%–25% relative to reference agents.Citation50 The regulatory framework and evidence requirements of the US biosimilars program involve a stepwise approach that relies heavily on analytical methods to demonstrate, through the “totality of evidence” (i.e., all available analytical, nonclinical, and clinical data), that a proposed biosimilar functions the same way as its reference product.Citation51,Citation52

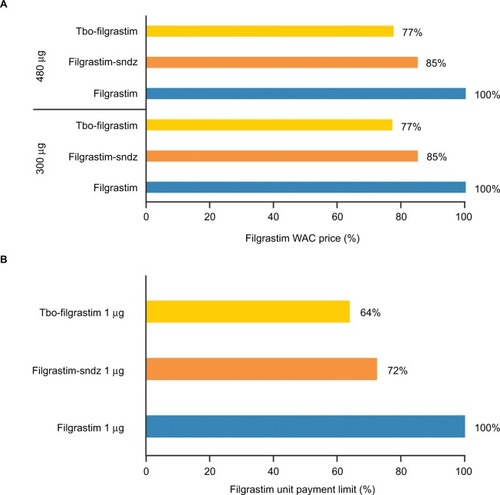

Biosimilars have been available globally since 2008, with the first US biosimilar, the G-CSF filgrastim-sndz, available in the USA since September 2016.Citation53,Citation54 Wholesale acquisition costs (WACs) in the USA for 2017 show a 15% discount for biosimilar filgrastim-sndz over filgrastim; a recent cost-efficiency analysis determined that prophylaxis with filgrastim-sndz was associated with consistently significant cost savings over filgrastim and pegfilgrastim.Citation55,Citation56 The alternate filgrastim agent, tbo-filgrastim (which is not a biosimilar in the USA and is approved for only one filgrastim indication), is available at a 23% discount compared to the WAC for filgrastim ().Citation57 Based on CMS payment limits (i.e., average sales price plus 6%) for fourth quarter of 2017, the payment limit for biosimilar filgrastim-sndz was 28% lower than for filgrastim, while for alternate agent tbo-filgrastim, pricing was 36% lower than for filgrastim ().Citation58 Thus, the filgrastim biosimilar and alternate agent provide cost savings under the pricing available to commercial payers and CMS payment limits.

Figure 3 Commercial price comparison for short-acting G-CSFs (filgrastim-sndz, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim) based on the fourth quarter of 2017 (A) WAC/average wholesale price in the USACitation57 and (B) CMS payment limits (average sales price + 6%).Citation58

Abbreviations: AWP, average wholesale price; µg, microgram; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; G-CSFs, granulocyte-colony stimulating factors; WAC, wholesale acquisition cost.

Multiple biosimilars are expected to obtain US FDA approval and enter the US market in the next 2–3 years as patent protection of reference supportive care drugs have come to the end of term recently or are expiring soon ().Citation59–Citation61 As of this writing, filgrastim-sndz is the only approved biosimilar for supportive oncology care under the US FDA BPCI, but in May 2017, the US FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee recommended approval of an epoetin alfa biosimilar across all licensed indications of the reference product.Citation62,Citation63 Also regarding biosimilar supportive care, Biologics License applications for four proposed bio-similars of G-CSF pegfilgrastim have been under review by the US FDA as of June 2017Citation64–Citation66; however, two of these applications were rejected and two others were still pending as of this writing. Biosimilars of targeted therapies bevacizumab (September 2017) and trastuzumab (December 2017) have recently been approved by the US FDA. Also in 2017, the US FDA has accepted a new Biologics License Application for a filgrastim biosimilar (September)Citation67 as well as biosimilars of rituximabCitation68 and trastuzumab.Citation68–Citation70 As more biosimilars become available after receiving regulatory approval, adoption in clinical practice is expected to increase. Biosimilar therapies are expected to improve access and to reduce overall pharmaceutical expenditures.

Value-based oncology frameworks

With ongoing concerns about the escalating costs of cancer care, a number of US professional and private organizations have developed value assessment frameworks to define and measure the value of oncology drugs and other therapies.Citation28,Citation71–Citation75 The overarching objectives of these frameworks differ, with some tailored to support physicians and patients in making informed, evidence-based treatment decisions, and others designed as tools to assist in coverage or reimbursement decisions. To date, however, these frameworks provide suggested guidance only; none has been implemented in US clinical practice or in a payer environment.

Outside of the USA, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and decision-making bodies in and many other countries use a health technology assessment (HTA) approach, which includes cost-effectiveness models and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, for health care reimbursement decision making. While it could be argued that countries using HTAs include some measure of value-based care, it should be noted that the National Health Service in England has studied incentive programs and value-based payments as a means to address inequalities in health care, but comprehensive programs have not been implemented as of this writing.Citation76

The CMS value-based care programs

The CMS has developed value-based care programs that reward health care providers with incentive payments for improving the quality of care they provide to Medicare beneficiaries. In the future, it is anticipated that CMS payments will be increasingly tied to measured performance in oncology care.Citation77

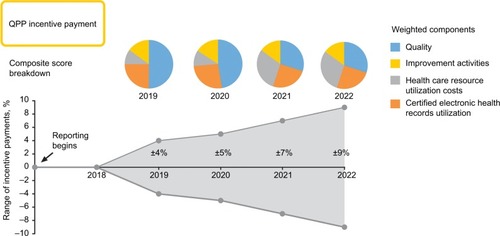

The CMS Quality Payment Program (QPP)

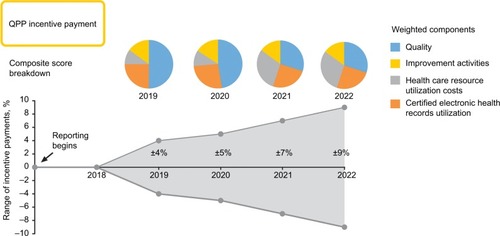

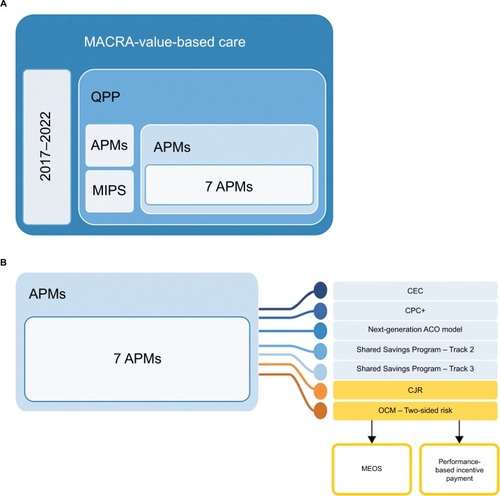

Fee-for-service (FFS) is a common US payment model in which medical services are not bundled, but paid for individually, thus incentivizing provision of high-quantity (but not necessarily high-quality) health care. An underlying tenant of value-based care is to move away from the FFS model and toward performance-based payments. In October 2016, the CMS finalized the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015Citation78 that implemented the QPP (). The QPP began in January 2017, with payment adjustments based on performance to be fully implemented by January 2019.Citation79 The QPP offers payment according to one of two tracks: 1) a Merit-based Incentive Payment System linked to performance including following defined, evidence-based clinical quality measures, and 2) Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs)Citation80 that give financial incentives to clinicians to provide high-quality and cost-efficient care ().Citation78,Citation81,Citation82 One of the Advanced APMs is the Oncology Care Model (OCM).Citation81,Citation83

Figure 4 OCM key drivers of cost reduction.

Figure 5 Range and weighted components of payments in the incentive payment program under the QPP.

Note: 2022 weighted components assumed, based on 2021 requirements.

Abbreviation: QPP, quality payment program.

Notes: Data from Quality Payment Program, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.Citation86 (A) Overview of payment programs under MACRA. (B) Overview of the Advanced Payment Models, including details on the OCM.

Abbreviations: APM, Alternative Payment Model; ACO, Accountable Care Organization; CEC, Comprehensive ESRD Care; CJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement; CPC+, Comprehensive Primary Care Plus; MACRA, Medicare Access and CHiP Reauthorization Act of 2015; MEOS, Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System; OCM, Oncology Care Model; QPP, Quality Payment Program.

The CMS OCM

In response to rising cancer treatment costs, in June 2016, the CMS launched a new, voluntary OCMCitation84,Citation85 as part of its broader initiative to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of specialty care; the program aims to provide higher quality, more coordinated oncology care at the same or lower cost to Medicare than traditional FFS payments ().Citation86 The OCM program ties payments to provider performance based on meeting specified quality metrics and practice reforms, with some practices already entering into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care involving chemotherapy administration to patients with cancer. As of this writing, the program is scheduled for 2017 through 2022. In July 2017, 192 practices and 14 commercial payers were participating in the OCM.Citation84

The OCM incorporates a two-part payment system for physician practices: a per-beneficiary Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services (MEOS) payment and a performance-based incentive payment (). The MEOS payment assists participating practices in effectively managing and coordinating episodes of care for oncology patients. The performance-based incentive payment is calculated retrospectively on a semiannual basis, based on the practice’s achievements in quality measures and reductions in Medicare expenditures.

The role of biosimilars in value-based oncology care programs

The Advanced APM track of the QPP is designed to give Medicare providers greater flexibility in delivering value-based care tailored to the type of care they provide. As specific examples of Advanced APMs, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) two-sided risk models and OCM were developed to deliver more effective and efficient specialty care through the provision of higher-quality, more coordinated care at the same or lower cost to Medicare as the traditional FFS model, utilizing participant-reported quality metric data to measure and reward high-value oncology care. Participants in the OCM and other similar incentives have an opportunity to play a key role in identifying clinical care practices to meet CMS program assessment goals including patient experience, reduced shared cost, and improved patient outcomes.

Biosimilars offer potential benefits under the OCM, including enhanced affordability and increased access to biologic treatments, along with the improved outcomes and HRQoL associated with biologics in both cancer treatment and supportive care. For example, the use of G-CSF as supportive care in 1,655 patients receiving standard-of-care chemotherapy for breast cancer reduced the incidence of neutropenia, which led to increased dose administration of the primary treatment and improved survival outcomes.Citation87 Availability of biosimilars in the oncology setting in the European Union has expanded patient access to treatment that previously may have been unavailable due to cost.Citation39 Economic modeling studies from Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom have shown cost savings along with expanded access to supportive care treatments including biosimilar filgrastimCitation88,Citation89 and biosimilar epoetin alfa,Citation90 compared with their respective reference biologics. This is illustrated by a budget impact analysis of real-world data for biosimilar rituximab (for rheumatology and cancer) in 28 European countriesCitation91 and by a recent Croatian study evaluating the budget impact of biosimilar trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer.Citation92 These European examples provide insight into possible cost-savings scenarios with biosimilars in the USA; however, due to the unique nature of the US health care market, it is unknown whether cost savings from biosimilars observed in Europe and elsewhere will manifest in the USA once a greater range of biosimilars used in cancer care are approved and available for use.

Biosimilars may offer a more affordable alternative to biologics as well as result in overall price decreases from market competition, which could result in substantial costsavings in the USA.Citation37,Citation93–Citation97 These benefits have been demonstrated for biosimilar filgrastim, for which CMS (ASP + 6%) pricing shows a 28% discount over the reference biologic. The Rand Corporation reports that savings to the US health care system incurred from the use of biosimilars over biologics range from an estimated $13 billion to $66 billion over the 10-year period between 2014 and 2024.Citation98 It is anticipated that the expanded treatment choices provided by biosimilars will open up new opportunities to improve value and care delivery. With biosimilar filgrastim available in the USA and biosimilar epoetin alfa expected to be available soon, the potential for clinicians to utilize these two supportive care biosimilars in oncology care, along with biosimilar targeted therapies, could be an important component in meeting MSSP and OCM objectives to improve the quality of care while reducing costs.

Realization of cost savings possible from biosimilars, however, will require that biosimilars are utilized.Citation99 Results of a 2015–2016 survey led by the Biosimilars ForumCitation100 showed that major knowledge gaps about biosimilars and their potential use in clinical practice still exist among US specialty physicians, including oncologists. Key gaps include defining biologics versus biosimilars in the context of biosimilarity, understanding the approval process and the use of the “totality of evidence” approach by the US FDA for biosimilar evaluation, understanding the evidence requirements for demonstration of safety and immunogenicity of a biosimilar versus its reference product, understanding the rationale for indication extrapolation, and defining interchangeability in the context of pharmacy-level substitution.

US physicians are now becoming more receptive to prescribing biosimilars, as a potentially important way to reduce drug costs and open access to effective therapies.Citation101,Citation102 A recent survey showed that efficacy (89%), safety (81%), and patient costs (71%) were the most important factors in determining whether US physicians would prescribe biosimilars overall, with discounts being a key influencer in anticipated prescribing patterns.Citation102 As additional biosimilars are approved in the USA and awareness grows, it is anticipated that biosimilar uptake and utilization will increase. There is a need to educate US physicians about biosimilars and to raise awareness among US payers and patients as well as health care providers in order to increase utilization of these potentially cost-saving therapies.

Conclusion

The goal of value-based care in oncology is to improve the quality of care, while containing costs. Advanced APMs such as the MSSP two-sided risk models and OCM are examples of a shift away from the traditional volume-based FFS model. For the OCM, this objective targets Medicare beneficiaries through an episode-based payment model that financially incentivizes high-quality, coordinated care. In moving toward a value-based specialized care system, payers recognize and reward providers who proactively seek to improve the patient experience and health outcomes. Biosimilars may provide an additional tool for providers participating in value-based care initiatives such as the MSSP and OCM, resulting in cost savings and efficiencies in the delivery of high-value care through expanded use of biologic treatment and supportive care agents during episodes of care. These savings may then be realized through the MSSP, OCM, or other incentive programs, with benefits passed on to health care providers, payers, and patients alike.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Robyn Fowler, PhD, Patricia McChesney, PhD, CMPP, and Karen Smoyer, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and funded by Pfizer Inc. Financial support for this review was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Disclosure

Dr Patel has been a consultant to Pfizer Inc at advisory boards. Dr Arantes Jr, Ms Tang, and Dr Fung are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FrankRGRegulation of follow-on biologicsN Engl J Med2007357984184317761588

- PasinaLCasadeiGNobiliABiological agents and biosimilars: essential information for the internistEur J Intern Med201633283527342030

- ZelenetzADAhmedIBraudELNCCN biosimilars white paper: regulatory, scientific, and patient safety perspectivesJ Natl Compr Canc Netw20119Suppl 4S1S22

- HusIFollow-on biologics in oncology – the need for global and local regulationsContemp Oncol (Pozn)201216646146623788931

- KuhlmannMCovicAThe protein science of biosimilarsNephrol Dial Transplant200621Suppl 5v4v816959791

- MorrowTFelconeLHDefining the difference: what makes biologics uniqueBiotechnol Healthc2004142429

- BuskeCOguraMKwonHCYoonSWAn introduction to biosimilar cancer therapeutics: definitions, rationale for development and regulatory requirementsFuture Oncol20171315s516

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration [webpage on the Internet]Information on Biosimilars2016 https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Devel-opmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/Accessed May 18, 2017

- U.S. Food Drug AdministrationScientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product: guidance for industry2015 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/DrugsGuidanceCompliance-RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291128.pdfAccessed May 18, 2017

- CamachoLHCurrent status of biosimilars in oncologyDrugs201777998599728477160

- HealthIMSDevelopments in cancer treatments, market dynamics, patient access and valueGlobal oncology trend report 20152015 http://keionline.org/sites/default/files/IIHI_Oncology_Trend_Report_2015.pdfAccessed May 17, 2017

- SullivanRPeppercornJSikoraKDelivering affordable cancer care in high-income countriesLancet Oncol2011121093398021958503

- ChanDLHSegelovEWongRSEpidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors for metastatic colorectal cancerCochrane Database Syst Rev20176CD00704728654140

- PorterDLLevineBLKalosMBaggAJuneCHChimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemiaN Engl J Med2011365872573321830940

- BangYJVan CutsemEFeyereislovaAToGA Trial InvestigatorsTrastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trialLancet2010376974268769720728210

- SaltzLBClarkeSDiaz-RubioEBevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III studyJ Clin Oncol200826122013201918421054

- ArgirisAHarringtonKJTaharaMEvidence-based treatment options in recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neckFront Oncol201777228536670

- VansteenkisteJPirkerRMassutiBDouble-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of darbepoetin alfa in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapyJ Natl Cancer Inst200294161211122012189224

- DammaccoFCastoldiGRodjerSEfficacy of epoetin alfa in the treatment of anaemia of multiple myelomaBr J Haematol2001113117217911328297

- IconomouGKoutrasARigopoulosAVagenakisAGKalofonosHPEffect of recombinant human erythropoietin on quality of life in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: results of a randomized, controlled trialJ Pain Symptom Manage200325651251812782431

- OsterborgABoogaertsMACiminoRRecombinant human erythropoietin in transfusion-dependent anemic patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – a randomized multicenter study. The European Study Group of Erythropoietin (Epoetin Beta) Treatment in Multiple Myeloma and Non-Hodgkin’s LymphomaBlood1996877267526828639883

- WilsonJYaoGLRafteryJA systematic review and economic evaluation of epoetin alpha, epoetin beta and darbepoetin alpha in anaemia associated with cancer, especially that attributable to cancer treatmentHealth Technol Assess200711131202iiiiv

- CoiffierBBoogaertsMKaineCImpact of Epoetin Beta Versus Standard Care on Quality of Life in Patients with Malignant Disease6th Congress of the European Haematology AssociationFrankfurt, GermanyJune 2001 Abstract no. 194

- INC ResearchThe State of Biosimilars, A FirstWord Perspectives Report Available from: http://www.firstwordplus.com/images/ads/TheStateofBiosimilars.pdfAccessed May 18, 2017

- ElkinEBBachPBCancer’s next frontier: addressing high and increasing costsJAMA2010303111086108720233828

- MariottoABYabroffKRShaoYFeuerEJBrownMLProjections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020J Natl Cancer Inst2011103211712821228314

- National Cancer Institute [webpage on the Internet]Cancer prevalence and cost of care projections2017 https://costprojections.cancer.gov/Accessed June 26, 2017

- SchnipperLEDavidsonNEWollinsDSAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment optionsJ Clin Oncol201533232563257726101248

- IMS HealthMedicines use and spending in the USA review of 2015 and outlook to 20202016 https://morningconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/IMS-Institute-US-Drug-Spending-2015.pdfAccessed May 17, 2017

- IMS HealthTop 20 global products 20152015 http://www.imshealth.com/files/web/Corporate/News/Top-Line%20Market%20Data/Top_20_Global_Products_2015.pdfAccessed May 17, 2017

- de SouzaJAYapBJWroblewskiKMeasuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST)Cancer2017123347648427716900

- O’ConnorJMKircherSMde SouzaJAFinancial toxicity in cancer careJ Comm Supp Oncol2016143101106

- Casilla-LennonMMChoiSKDealAMFinancial toxicity in bladder cancer patients – reasons for delay in care and effect on quality of lifeJ Urol201819951166117329155338

- HuntingtonSFWeissBMVoglDTFinancial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot studyLancet Haematol2015210e408e41626686042

- European Medicines AgencyBiosimilars in the EU: information guide for healthcare professionals2017 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Leaflet/2017/05/WC500226648.pdfAccessed May 24, 2017

- SimoensSBiosimilar medicines and cost-effectivenessClinicoecon Outcomes Res20113293621935330

- IMS Institute for Healthcare InformaticsDelivering on the potential of biosimilar medicines: the role of functioning competitive markets [updated March 2016]. http://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Healthcare%20Briefs/Documents/IMS_Institute_Biosimilar_Brief_March_2016.pdfAccessed June 14, 2017

- European Medicines Agency [webpage on the Internet]European public assessment reports (EPAR) for human medicines: biosimilars2017 http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d125http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?mid=WC0b01ac058001d125&searchType=name&taxonomyPath=Diseases&searchGenericType=generics&keyword=Enter+keywords&alreadyLoaded=true&curl=pages%2Fmedicines%2Flanding%2Fepar_search.jsp&status=Authorised&status=Withdrawn&status=Suspended&status=Refused¤tCategory=Cancer&treeNumber=&searchTab=&pageNo=2Accessed August 18, 2017

- GasconPTeschHVerpoortKClinical experience with Zarzio® in Europe: what have we learned?Supp Care Cancer2013211029252932

- AraujoFCGoncalvesJFonsecaJEPharmacoeconomics of biosimilars: what is there to gain from them?Curr Rheumatol Rep20161885027402107

- European Medicines AgencyApplications for new human medicines under evaluation by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use: August 2017EMA/506776/2017 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2017/08/WC500233092.pdfAccessed August 18, 2017

- Truven Health AnalyticsBiosimilar Market Access, A FirstWord Perspectives ReportTruven Health Analytics, an IBM Company Ann ArborMI, USA102016

- Mestre-FerrandizJTowseABerdudMBiosimilars: how can payers get long-term savings?Pharmacoeconomics201634660961626792791

- Informatics IIfHThe Impact of Biosimilar Competition in EuropeParsippany, NJ52017

- AbrahamIHanLSunDMacDonaldKAaproMCost savings from anemia management with biosimilar epoetin alfa and increased access to targeted antineoplastic treatment: a simulation for the EU G5 countriesFuture Oncol20141091599160925145430

- ManolisCHRajasenanKHarwinWMcClellandSLopesMFarnumCBiosimilars: opportunities to promote optimization through payer and provider collaborationJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201622Suppl 9S3S9

- FarhatFOthmanAel KarakFKattanJReview and results of a survey about biosimilars prescription and challenges in the Middle East and North Africa regionSpringerplus201651211328090427

- BennettCLChenBHermansonTRegulatory and clinical considerations for biosimilar oncology drugsLancet Oncol20141513E594E60525456378

- GovernmentUSBiologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, sections 7001–7003Public law no. 111-1482009 https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/UCM216146.pdfAccessed May 18, 2017

- USCB OfficeS 1695 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 20072008 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/41712Accessed June 28, 2017

- ChristlLDeisserothA webpage on the InternetDevelopment and approval of biosimilar products2015 http://www.ascopost.com/issues/march-25-2015/development-and-approval-of-biosimilar-products/Accessed May 18, 2017

- ChristlLAWoodcockJKozlowskiSBiosimilars: the US regulatory frameworkAnnu Rev Med20176824325427813877

- NovartisAG [news release] [webpage on the Internet]Sandoz launches Zarxio™ (filgrastim-sndz), the first biosimilar in the United States2015 https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/sandoz-launches-zarxiotm-filgrastim-sndz-first-biosimilar-united-statesAccessed June 14, 2017

- RaedlerLAZarxio (filgrastim-sndz): first biosimilar approved in the United StatesAm Health Drug Benefits20169 Spec Feature15015427668063

- McBrideACampbellKBikkinaMMacDonaldKAbrahamIBaluSCost-efficiency analyses for the US of biosimilar filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim with on-body injector in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropeniaJ Med Econ201720101083109328722494

- McBrideABaluSCampbellKBikkinaMMacDonaldKAbrahamIExpanded access to cancer treatments from conversion to neutro-penia prophylaxis with biosimilar filgrastim-sndzFuture Oncol201713252285229528870106

- RED BOOK Online® pricing: Filgrastim, Filgrastim-sndz, Tbo-filgrastim [webpage on the Internet]2017 Truven Health Analytics, an IBM Company2017 https://truvenhealth.com/products/micromedex/product-suites/clinical-knowledge/red-bookAccessed May 24, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [webpage on the Internet]2017ASP Drug Pricing Files72017 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice/2017ASPFiles.htmlAccessed August 23, 2017

- JacobsIEwesuedoRLulaSZacharchukCBiosimilars for the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of published evidenceBioDrugs201731113628078656

- RugoHSLintonKMCerviPRosenbergJAJacobsI webpage on the InternetA clinician’s guide to biosimilars in oncologyCancer Treat Rev201646737927135548

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI)Biologicals patent expiries2015 http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Biologicals-patent-expiriesAccessed May 19, 2017

- Business Wire [news release] [webpage on the Internet]FDA Advisory Committee recommends approval of Pfizer’s proposed biosimilar to Epogen/Procrit across all indications2017 https://www.biosimilarde-velopment.com/doc/fda-advisory-committee-recommends-approval-of-pfizer-s-proposed-biosimilar-0001Accessed June 26, 2017

- FoodUSAdministrationDrugEpoetin Hospira: FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Document2017 https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/Oncologic-DrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM559968.pdfAccessed August 21, 2017

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) [webpage on the Internet]Apotex petitions FDA over Neulasta biosimilars2017 http://www.gabionline.net/Guidelines/Apotex-petitions-FDA-over-Neulasta-biosimilarsAccessed June 28, 2017

- Mylan [news release] [webpage on the Internet]US FDA Accepts Biologics License Application (BLA) for Mylan and Biocon’s Proposed Biosimilar Pegfilgrastim for Review2017 http://newsroom.mylan.com/2017-02-16-U-S-FDA-Accepts-Biologics-License-Application-BLA-for-Mylan-and-Biocons-Proposed-Biosimilar-Pegfilgrastim-for-ReviewAccessedJune 28, 2017

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI) [webpage on the Internet]FDA accepts application for pegfilgrastim biosimilar2015 http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/FDA-accepts-application-for-pegfilgrastim-biosimilarAccessed June 28, 2017

- Adello Biologics [webpage on the Internet]FDA Accepts Adello’s Biosimilar Biologics License Application (BLA) for a Proposed Filgrastim Biosimilar2017 http://adellobio.com/news/2017/fda-accepts-adellos-biosimilar-biologics-license-application-bla-for-a-proposed-filgrastim-biosimilarAccessed November 20, 2017

- Celltrion and Teva Announce U.S.FDA Acceptance of Biologics License Application for Proposed Biosimilar to Herceptin® (trastuzumab) [press release] http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=251945&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=22901237312017

- U.S. FDA accepts Biologics License Application (BLA) for Mylan and Biocon’s Proposed Biosimilar Trastuzumab [press release] http://investor.mylan.com/news-releases/news-release-details/us-fda-accepts-biologics-license-application-bla-mylan-and1122017

- Amgen and Allergan Submit Biosimilar Biologics License Application for ABP 980 to US Food And Drug Administration [press release] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/amgen-and-allergan-submit-biosimilar-biologics-license-application-for-abp-980-to-us-food-and-drug-administration-300496238.html7312017

- SorensonCLavezzariGDanielGAdvancing value assessment in the United States: a multistakeholder perspectiveValue Health201720229930728237214

- SchnipperLEDavidsonNEWollinsDSUpdating the American Society of Clinical Oncology value framework: revisions and reflections in response to comments receivedJ Clin Oncol201634242925293427247218

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [webpage on the Internet]DrugAbacus methods2017 http://drugpricinglab.org/tools/louisiana-budget-allocator/methods/Accessed May 18, 2017

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network [webpage on the Internet]NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guideliness) with NCCN Evidence Blocks™2017 https://www.nccn.org/evi-denceblocks/Accessed May 18, 2017

- Institute for Clinical and Economic ReviewICER value assessment framework. 2017 https://icer-review.org/methodology/icers-methods/icer-value-assessment-framework/Accessed May 18, 2017

- SMCRe-submission: olaparib, 50mg, hard capsules (Lynparza®) SMC No. (1047/15) AstraZeneca UK.UKScottish Medicies Consortium2016SMC No. 1047/15

- CloughJDKamalAHOncology care model: short- and long-term considerations in the context of broader payment reformJ Oncol Pract201511431932126060221

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [webpage on the Internet]The Quality Payment Program2016 [news release]; https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-10-25.htmlAccessed August 21, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health & Human ServicesThe Quality Payment Program Overview Fact Sheet2016 https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/Quality_Payment_Program_Overview_Fact_Sheet.pdfAccessed August 22, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health & Human Services [webpage on the Internet]Quality Payment Program2016 https://qpp.cms.gov/Accessed August 21, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health & Human ServicesThe Quality Payment Program [slide presentation]2016 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Quality-Payment-Program-Long-Version-Executive-Deck.pdfAccessed August 21, 2017

- DongLFPelizzariPM webpage on the InternetAdvanced APMs and Qualifying APM Participant Status2016 http://www.milliman.com/insight/2016/Advanced-APMs-and-Qualifying-APM-Participant-status/Accessed August 31, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. U.S. Department of JusticeMedicare Shared Savings Program ACO: Preparing to Apply for the 2018 Program Year [slide presentation]2017 https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/2017-04-06-SSP-Presentation.pdfAccessed August 31, 2017

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [webpage on the Internet]Oncology Care Model2017 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/Accessed August 18, 2017

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [webpage on the Internet]Fact Sheets: Oncology Care Model2016 https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-06-29.htmlAccessed May 19, 2017

- (CMS) USCfMMSOncology Care Model: Key Drivers & Change Package https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/ocm-keydrivers-change-pkg.pdf962017Accessed September 28, 2017

- ChanAMcGregorSLiangWBUtilisation of primary and secondary G-CSF prophylaxis enables maintenance of optimal dose delivery of standard adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: an analysis of 1655 patientsBreast201423567668225108452

- AaproMCornesPAbrahamIComparative cost-efficiency across the European G5 countries of various regimens of filgrastim, biosimilar filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropeniaJ Oncol Pharm Pract201218217117921610020

- SunDAndayaniTMAltyarAMacDonaldKAbrahamIPotential cost savings from chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim and expanded access to targeted antineoplastic treatment across the European Union G5 countries: a simulation studyClin Ther201537484285725704107

- AaproMCornesPSunDAbrahamIComparative cost efficiency across the European G5 countries of originators and a biosimilar erythropoiesis-stimulating agent to manage chemotherapy-induced anemia in patients with cancerTher Adv Med Oncol2012439510522590483

- GulacsiLBrodszkyVBajiPRenczFPentekMThe rituximab bio-similar CT-P10 in rheumatology and cancer: a budget impact analysis in 28 European countriesAdv Ther20173451128114428397080

- CesarecALikićRBudget impact analysis of biosimilar trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer in CroatiaAppl Health Econ Health Policy2016152277286

- Farfan-PortetMIGerkensSLepage-NefkensIVinckIHulstaertFAre biosimilars the next tool to guarantee cost-containment for pharmaceutical expenditures?Eur J Health Econ201415322322824271016

- BocciaRJacobsIPopovianRde Lima LopesGJrCan biosimilars help achieve the goals of US health care reform?Cancer Manag Res2017919720528615973

- Kyodo [webpage on the Internet]Generic Drugs to be Priced at 10% Less From AprilThe Japan Times Online2015 https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/12/02/national/science-health/generic-drugs-to-be-priced-at-10-less-from-april/#.Wal0irKGO1tAccessed September 8, 2017

- MominZWijayaCBernardoP webpage on the InternetWill Asia Go Big in Biosimilars Adoption and Manufacturing?Biosimilar Development 20175182017 https://www.biosimilardevelopment.com/doc/will-asia-go-big-in-biosimilars-adoption-and-manufacturing-0001Accessed September 8, 2017

- Japan Announces Proposed Plan to Reduce Biosimilar and Generic Drug Prices [webpage on the Internet]Big Molecule Watch2016 http://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/2016/02/03/japan-announces-proposed-plan-to-reduce-biosimilar-and-generic-drug-prices/Accessed September 8, 2017

- MulcahyAWPredmoreZMattkeSThe cost savings potential of biosimilar drugs in the United States [updated 2014] https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE100/PE127/RAND_PE127.pdfAccessed June 14, 2017

- TaberneroJVyasMGiulianiRBiosimilars: a position paper of the European Society for Medical Oncology, with particular reference to oncology prescribersESMO Open201716e00014228848668

- CohenHBeydounDChienDAwareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physiciansAdv Ther201733122160217227798772

- FelixAEGuptaACohenJPRiggsKBarriers to market uptake of biosimilars in the USGaBI J201433108115

- Market Wired [webpage on the Internet]Nearly half of US physicians say they will prescribe more biosimilars, according to new data from InCrowd [news release]2016 http://www.marketwired.com/press-release/nearly-half-us-physicians-say-they-will-prescribe-more-biosimilars-according-new-data-2102567.htmAccessed June 14, 2017

- MicklusAHot Topic: Biosimilars Market Access in the USDatamonitor Healthcare, Informa UK LimitedLondon, UK2017