Abstract

Objective

Research efforts have investigated therapies targeting tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. We performed a pooled analysis to determine the frequency of severe adverse effects in patients with soft tissue sarcoma treated with pazopanib, sorafenib and sunitinib.

Materials and methods

We performed a comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, Ovid, the Cochrane Library and Embase databases from the drugs’ inception to May 2017 to identify clinical trials. All-grade and severe adverse events (AEs; grade≥3) were analyzed.

Results

A total of 10 trials published between 2009 and 2016, including 843 patients, were eligible for analysis. We included 424 patients (three studies) who received pazopanib 800 mg daily, 353 patients (five studies) who received sorafenib 400 mg twice daily and 66 patients (two studies) who received sunitinib 37.5 mg daily. The incidence of AEs is different among the three VEGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Pazopanib showed higher incidence of all-grade nausea, diarrhea and hypertension compared with sorafenib and sunitinib. However, patients in the sorafenib group experienced a significantly higher frequency of all-grade rash (26.1%), hand–foot syndrome (33.4%) and mucositis (38.5%). The difference was highly significant for sorafenib vs. pazopanib in the incidence of all-grade rash (odds ratio [OR] 1.649, 95% CI 1.086–2.505, P=0.023), hand–foot syndrome (OR 3.096, 95% CI 1.271–7.544, P=0.009) and mucositis (OR 4.562, 95% CI 2.132–9.609, P<0.001). Moreover, the frequency of grade ≥3 mucositis was significantly higher in the sunitinib group compared with the pazopanib or sorafenib group (7.6% vs. 1.3%, OR 6.448, 95% CI 1.499–27.731, P=0.013).

Conclusion

Statistically significant differences in certain common adverse effects, such as all-grade and severe AEs, were detected among pazopanib, sorafenib and sunitinib in the current study. Early and prompt management is critically needed to avoid unnecessary dose reductions and treatment-related discontinuations.

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) are a group of rare mesenchymal cancers that include approximately 50 histological subtypes and comprise approximately 1% of all adult cancers.Citation1,Citation2 Surgery with or without radiotherapy is the primary treatment for early-stage localized STS.Citation3,Citation4 The conventional treatment for patients with inoperable or metastatic STSs is an anthracycline (usually doxorubicin), either as a monotherapy or in combination with ifofamide.Citation5 However, the prognosis of metastatic or advanced STS is poor.

Given the need for improved therapies, investigations into novel treatments for advanced STS are continuing. Recently, studies have been performed to test anti-angiogenic treatment, and efforts have been focused on therapies targeting tyrosine kinase signaling pathways.Citation6–Citation8 The small molecule vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor, pazopanib, is a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with high affinity against VEGFR-1/2/3 and with a lower affinity against PDGFR-α/β, FGFR-1/2 and stem cell factor receptor (c-KitR).Citation9 Based on the clinical trials, pazopanib was determined to be well tolerated in metastatic or advanced STS and demonstrated antitumor activity in non-liposarcoma.Citation10,Citation11 Therefore, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have approved pazopanib for the treatment of advanced STS in those who have received prior chemotherapy.Citation12

Sorafenib, also a small molecule B-raf and VEGFR inhibitor, is potentially useful in several specific sarcoma subtypes, such as angiosarcomas.Citation13 Moreover, sorafenib in patients with solid tumors indicated a promising 30% PFR12 in patients with metastatic sarcomas.Citation14 Furthermore, in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs) with the loss of NF1 and the activation of the ras–raf signaling pathway,Citation15–Citation17 sorafenib demonstrated activity. Based on preclinical data, the level of tumor growth inhibition for pazopanib was similar to that for sorafenib.Citation18–Citation20

Sunitinib is also a multi-targeted TKI with activity against VEGFRs1/2/3, PDGFR-α/β, KIT, FLT3, RET and CSF-1.Citation21 The role of sunitinib has also been extensively studied in STS. Furthermore, clinical efficacy has been indicated in patients with advanced STS, predominantly in liposarcomas, leimyosarcomas,Citation22 solitary fibrous tumorsCitation23 and alveolar STSs.Citation24

In the past decade, three TKIs have been developed as angiogenesis inhibitors and showed their antitumor response in several solid tumors.Citation10,Citation25–Citation29 However, the use of VEGFR-TKIs is limited by their different side effects, in which the precise underlying mechanism often remains unclear. The difference in the toxicity pattern among pazopanib, sunitinib and sorafenib remains unclear.Citation30 Although pazopanib is the only one which has been approved by the FDA for patients with sarcoma, sunitinib and sorafenib have shown definite efficacy in some specific types of sarcomas. There is a great potential for TKIs in the treatment of patients with sarcoma. Notably, the three TKIs show a promising response rate in STS. Compliance with anticancer therapy is determined by their tolerability. Therefore, it is important to choose optimal TKIs by performing a pooled analysis of the occurrence of adverse events (AEs) based on data extracted from clinical trials of patients with STS.

Materials and methods

Study identification

The following computerized databases were used to search the relevant literature for clinical trials: PubMed, Web of Science, Ovid, the Cochrane Library and Embase, encompassing the period from the drugs’ inception to May 2017. The search keywords were “pazopanib,” “sunitinib,” “sorafenib,” and “sarcoma.” Abstracts from American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meetings were hand searched to scan for updated data and to identify new studies. In addition, duplicate data were removed, and the articles were screened to determine whether the article was relevant. Duplicate research or irrelevant articles were discarded after retrieval and review. Reference lists were also hand searched to identify any additional articles.

The study’s inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients ≥18 years or older with metastatic or locally advanced STS (non-GISTs); 2) intervention: pazopanib, sunitinib or sorafenib, not combined with other therapies; 3) sufficient data presented on treatment-related AEs (TRAEs), including all information about all-grade and grade ≥3 toxicity and 4) written in English. All case reports, letters, commentaries and reviews were excluded.

Data extraction and quality control

The first author’s name, publication year, therapeutic drug (pazopanib, sunitinib or sorafenib), number of patients evaluable for all-grade and grade ≥3 toxicity (nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, vomiting, hypertension, hand–foot syndrome, rash, elevated ALT, neutropenia, leukopenia and anemia, mucositis, number of patients experiencing treatment-related death [TRD] and withdrawal resulting from severe toxicity) were evaluated. Clinical trials were collected for patients receiving pazopanib 800 mg daily, sorafenib 400 mg twice daily and sunitinib 37.5 mg daily according to the FDA-recommended dose. Two studies including patients receiving sunitinib 50 mg daily were excluded.Citation22,Citation31 Studies were independently selected by two authors based on the aforementioned inclusion criteria.

The full texts of nonrandomized clinical trials were assessed using the 9-point Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Two investigators evaluated the studies independently. Studies were categorized into three broad perspectives, including selection, comparability and outcome for cohort studies or exposure for case–control studies. A score of 7 or greater was considered to be high quality. The risk of bias in the included studies was independently assessed by two investigators using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).Citation32 Two authors independently assessed each study under five main headings for the risk of bias.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests were used to compare the frequencies of AEs among three multiple receptor tyrosine kinases. All tests were two tailed, and statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the original selected studies

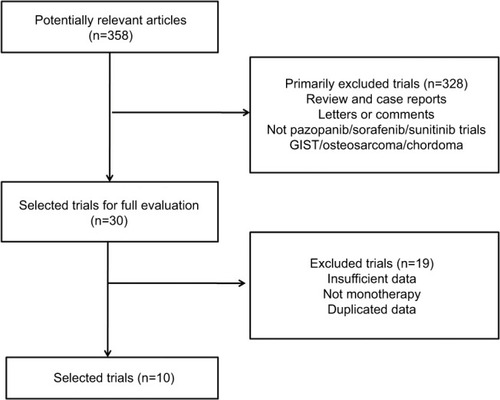

Based on our inclusion criteria, 10 clinical trials were identified to address multiple receptor tyrosine kinase-treated STSs (). Among the 10 trials published between 2009 and 2016, 843 patients with STS were eligible for the current study. The sample size of the eligible trials ranged from 14 to 239. We included 424 patients (three studies)Citation10,Citation11,Citation33 who received pazopanib, 353 patients (five studies)Citation13,Citation34–Citation37 who received sorafenib and 66 patients (two studies)Citation38,Citation39 who received sunitinib. All the patients received the multiple TKI alone. The primary characteristics of the included trials are listed in .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of trials included in the pooled analysis

Study quality assessment and risk of bias

The methodological quality of all non-RCTs (NRCTs; excluding abstracts and conference abstracts) is listed in . No major flaws of the included RCTs were detected in assessing their risk of bias (). However, the expected absence of a blinded intervention was a common caveat.

Frequency of all-grade TRAEs between different VEGFR-TKI types

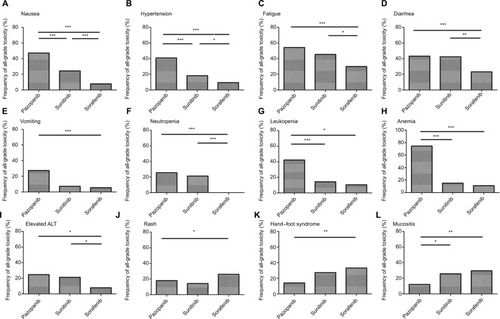

We analyzed the incidence and odds ratio (OR) of TRAEs by VEGFR-TKI in patients with STS. The incidence of all-grade nausea was highest with pazopanib (47.2%) followed by sunitinib (24.2%) and sorafenib (7.6%). The difference between incidence was highly significant for pazopanib vs. sunitinib (OR 2.799, 95% CI 1.539–5.088, P<0.001), sunitinib vs. sorafenib (OR 3.865, 95% CI 1.740–8.584, P=0.001) and pazopanib vs. sorafenib (OR 10.815, 95% CI 5.933–19.713, P<0.001; ).

Figure 2 Frequency of all-grade toxicity, including nausea (A), hypertension (B), fatigue (C), diarrhea (D), vomiting (E), neutropenia (F), leukopenia (G), anemia (H), elevated ALT (I), rash (J), hand–foot syndrome (K) and mucositis (L) among different multiple TKIs.

Note: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 indicate statistically significant differences.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

A similar pattern was observed in the frequency of all-grade hypertension. The incidence of all-grade hypertension was highest with pazopanib (40.9%) followed by sunitinib (18.2%) and sorafenib (9.3%). The difference between the incidences was highly significant for pazopanib vs. sorafenib (OR 6.723, 95% CI 4.451–10.155, P<0.001), sunitinib vs. sorafenib (OR 2.155, 95% CI 1.048–4.431, P=0.049) and pazopanib vs. sunitinib (OR 3.120, 95% CI 1.616–6.024, P<0.001; ).

For all-grade fatigue, the frequency was 54.3% for pazopanib, 45.5% for sunitinib and 30.0% for sorafenib. Significant differences were found between pazopanib vs. sorafenib (OR 2.772, 95% CI 2.045–3.757, P<0.001). Meanwhile, patients in the sunitinib group experienced significantly higher frequency of all-grade fatigue than patients in the sorafenib group (OR 1.942, 95% CI 1.137–3.317, P=0.021), whereas the difference between pazopanib vs. sunitinib was not significant (OR 1.428, 95% CI 0.845–2.413, P=0.185; ).

Similarly, the frequency of all-grade diarrhea was significantly greater in patients treated with pazopanib than in those treated with sorafenib (43.2% vs. 23.5%, OR 2.470, 95% CI 1.808–3.375, P<0.001). Moreover, statistical significance was observed between the sunitinib and sorafenib groups (42.4% vs. 23.5% OR 2.397, 95% CI 1.388–4.141, P=0.002), Nonetheless, there was no significant difference between the pazopanib and sunitinib cohort (43.2% vs. 42.4%, OR 1.031, 95% CI 0.610–1.741, P=1.000; ).

All-grade vomiting was significantly more common for pazopanib compared with sorafenib (27.4% vs. 5.4%, OR 6.183, 95% CI 3.324–11.501, P<0.001). However, statistical significance was not observed between the sorafenib and sunitinib groups (5.4% vs. 7.1%, OR 0.792, 95% CI 0.095–6.570, P=0.580). In addition, there was no significant difference between pazopanib and sunitinib (27.4% vs. 7.1%, OR 4.896, 95% CI 0.633–37.848, P=0.126; ).

The frequency of all-grade neutropenia differed significantly between pazopanib and sorafenib (25.4% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.283, 95% CI 1.186–1.387, P<0.001). Statistical significance was also observed between sunitinib and sorafenib (21.2% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.750, 95% CI 1.465–2.091, P=0.002). However, there was no significant difference between pazopanib and sunitinib (25.4% vs. 21.2%, OR 1.265, 95% CI 0.643–2.489, P=0.616; ). For all-grade leukopenia, patients in the pazopanib group also experienced significantly higher frequency than patients in the sorafenib group (42.3% vs. 10.4%, OR 6.293, 95% CI 3.352–11.814, P<0.001) and sunitinib group (42.3% vs. 14.3%, OR 4.390, 95% CI 0.947–20.347, P=0.048), whereas there was no significant difference between sunitinib and sorafenib (14.3% vs. 10.4%, OR 1.433, 95% CI 0.292–7.026, P=0.649; ). A similar pattern was observed in the frequency of all-grade anemia between pazopanib and sorafenib (74.6% vs. 12.8%, OR 20.022, 95% CI 7.278–55.085, P<0.001) and pazopanib and sunitinib (74.6% vs. 15.2%, OR 16.489, 95% CI 7.621–35.677, P<0.001), Nonetheless, there was no significant difference between the sunitinib and sorafenib groups (15.2% vs. 12.8%, OR 1.214, 95% CI 0.383–3.854, P=1.000; ).

Another common adverse effect, elevated all-grade ALT, was more common for pazopanib compared with sorafenib (24.7% vs. 7.7%, OR 3.907, 95% CI 2.159–7.069, P<0.001) and sunitinib vs. sorafenib (21.2% vs. 7.7%, OR 3.200, 95% CI 1.354–7.566, P=0.010). Statistical significance was not observed between pazopanib and sunitinib (24.7% vs. 21.2%, OR 1.221, 95% CI 0.603–2.471, P=0.730; ).

A further analysis of common skin and mucosa dysfunctions (rash, hand–foot syndrome and mucositis) was conducted among the three VEGFR-TKI types. Patients in the sorafenib group experienced a significantly higher frequency of all-grade rash (26.1%), hand–foot syndrome (33.4%) and mucositis (38.5%). The difference was highly significant for sorafenib vs. pazopanib for the incidence of all-grade rash (OR 1.649, 95% CI 1.086–2.505, P=0.023; ), hand–foot syndrome (OR 3.096, 95% CI 1.271–7.544, P=0.009; ) and mucositis (OR 4.562, 95% CI 2.132–9.609, P<0.001; ).

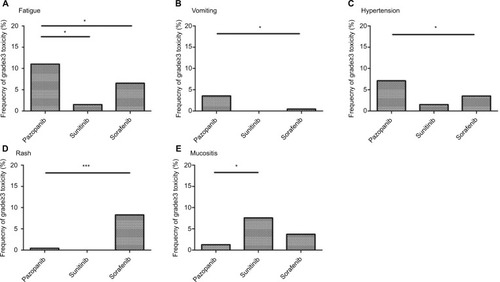

Frequency of severe TRAEs (grade ≥3) between different VEGFR-TKI types

Grade ≥3 fatigue was significantly more common for pazopanib compared with sorafenib (11.0% vs. 6.5%, OR 1.778, 95% CI 1.046–3.022, P=0.037) and sunitinib (11.0% vs. 1.5%, OR 8.053, 95% CI 1.089–59.555, P=0.012). Nonetheless, there was no significant difference between the sorafenib and sunitinib cohorts (6.5% vs. 1.5%, OR 4.530, 95% CI 0.601–34.141, P=0.149; ).

Figure 3 Frequency of AEs, grade≥3, including fatigue (A), vomiting (B), hypertension (C), rash (D) and mucositis (E) among different multiple TKIs.

Note: *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 indicate statistically significant differences.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

A similar pattern was observed in the frequency of grade ≥3 vomiting in the pazopanib vs. sorafenib groups (3.5% vs. 0.5%, OR 7.647, 95% CI 0.971–60.211, P=0.028), whereas there was no significant difference between pazopanib and sunitinib (3.5% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.051, 95% CI 1.024–1.079, P=1.000) or sorafenib and sunitinib (0.5% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.067, 95% CI 1.031–1.104, P=1.000; ).

Patients in the pazopanib group experienced a significantly higher frequency of severe hypertension than patients in the sorafenib group (7.1% vs. 3.4%, OR 2.143, 95% CI 1.069–4.298, P=0.032). However, the frequency of grade ≥3 hypertension did not differ significantly between the pazopanib and sunitinib groups (7.1% vs. 1.5%, OR 4.902, 95% CI 0.655–36.710, P=0.101). Moreover, statistical significance was not observed between the sorafenib and sunitinib groups (3.4% vs. 1.5%, OR 2.287, 95% CI 0.292–17.896, P=0.702; ).

Another common adverse effect, grade ≥3 rash, was less common for pazopanib compared with sorafenib (0.4% vs. 8.3%, OR 0.047, 95% CI 0.006–0.346, P<0.001). Statistical significance was not observed between pazopanib and sunitinib (0.4% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.059, 95% CI 1.028–1.091, P=1.000); likewise, it was not observed between sorafenib and sunitinib (8.3% vs. 0.0%, OR 1.049, 95% CI 1.023–1.075, P=0.613; ).

For grade ≥3 mucositis, the frequency was highest with sunitinib (7.6%), followed by sorafenib (5.1%) and pazopanib (1.3%). Statistical significance was observed in investigating the frequency of mucositis grade ≥3 for sunitinib vs. pazopanib (7.6% vs. 1.3%, OR 6.448, 95% CI 1.499–27.731, P=0.013; ).

As for grade ≥3 nausea, neutropenia, leukopenia, anemia, elevated ALT and hand–foot syndrome, no statistical significance was detected among all three cohorts (data not shown).

By pooled analysis, complete responses and partial responses were observed in 39 patients in the pazopanib group, 27 in the sorafenib group and five in the sunitinib group. Objective response rates were similar among the three groups ().

Identification of withdrawal toxicity and TRD for pazopanib vs. sorafenib

The overall frequency of AEs that resulted in treatment withdrawal for pazopanib and sorafenib was 11.1% (47 of 424 evaluable patients) and 11.0% (39 of 353 evaluable patients), respectively. No significant difference was observed among the two groups. However, a significant difference in AEs that resulted in TRD was observed between pazopanib and sorafenib (3.3% vs. 0.0, OR 1.620, 95% CI 1.480–1.733, P=0.029). The frequency of the overall TRD for pazopanib and sorafenib was 3.3% (eight of 239 evaluable patients) and 0.0% (zero of 139 evaluable patients), respectively.

Discussion

In the past decade, several small molecule TKIs, including pazopanib, sunitinib and sorafenib, have demonstrated clinical efficacy in STS.Citation10,Citation11,Citation13,Citation36,Citation38 However, the use of these inhibitors is limited by the occurrence of severe adverse effects, such as hypertension, rash and fatigue.Citation40,Citation41 Treatments that alleviate and prevent side effects ultimately lead to enhanced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients. The determination of frequency of TRAEs of different TKIs in STS may enable the early management of most susceptible patients. In this regard, there is a critical need to determine the frequency of AEs to reduce the risk of treatment-related withdrawal or death.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first pooled analysis in STS, focusing on the differences in TRAEs among pazopanib, sunitinib and sorafenib. In our analysis, pazopanib had the highest incidence of all-grade nausea, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, hypertension, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), neutropenia, leukopenia and anemia compared with sorafenib and sunitinib; likewise, the frequency of grade ≥3 fatigue, vomiting and hypertension was also the highest in pazopanib-treated patients. We further observed that the frequency of AEs that resulted in TRD was significantly different between the pazopanib and sorafenib groups. Conversely, the frequency of rash, hand–foot syndrome and mucositis was highest in the sorafenib group compared with the pazopanib and sunitinib groups, and sorafenib-treated patients had the highest incidence of grade ≥3 rash among the three groups. Moreover, the frequency of grade ≥3 mucositis was significantly higher in the sunitinib group compared with the pazopanib or sorafenib groups.

A double-blind, randomized crossover study sought to assess the preference between sunitinib and pazopanib for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).Citation42 This study observed that, for most of the AEs, especially fatigue, patients preferred pazopanib over sunitinib. In a meta-analysis, Santoni et alCitation43 demonstrated that sorafenib had a lower incidence of risk ratio (RR) of all-grade gastrointestinal (GI) events compared with pazopanib and sunitinib. However, these results have not focused on the STS subgroup. In addition, the differences in some common adverse effects of anti-angiogenesis, including rash, hand–foot syndrome and hypertension, among pazopanib, sunitinib and sorafenib, have not been determined. The different evaluation time points of adverse effects and different doses of TKIs in the studies may drive the different results. For example, in our article, we included patients who received pazopanib 800 mg daily and sunitinib 37.5 mg daily. However, Escudier et alCitation42 reported that patients with metastatic RCC were randomly assigned to pazopanib 800 mg/day for 10 weeks, a 2-week washout, and then sunitinib 50 mg/day (4 weeks on, 2 weeks off, 4 weeks on).

Imatinib mesylate is also a competitive inhibitor of tyrosine kinases selectively associated with c-Kit and platelet derived growth factor receptors.Citation44 Besides GIST, it has been registered for advanced/metastatic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSPs). Two Phase II trials formally proved the activity of the drug in this disease, with a 50% overall response rate leading to the registration for this disease.Citation45,Citation46 Similar activity has been shown in the rare fibrosarcomatous variant although with a more limited duration.Citation47,Citation48 Imatinib is therefore currently used in classical locally advanced DFSP and in metastatic fibrosarcomatous DFSP. Given that the good clinical response and limited dose-related effect of imatinib in DFSP may to some extent influence the result, we did not include imatinib in the pooled analysis.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study analyzed all published clinical trials and determined the statistical significance of severe AEs among VEGFR-TKIs. However, the small number of patients receiving sunitinib compared with those receiving pazopanib or sorafenib may to some extent be a limitation. Thus, a large sample size of prospective RCTs is required. Second, a portion of AE information was not obtained, even though we contacted the corresponding authors. Third, the association between treatment-related toxicities and clinical outcome in patients with VEGFR-TKI still remains to be elucidated. Further studies are urgently needed to understand the underlying mechanism of this association.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that different VEGFR-TKIs are associated with a significantly increased risk of treatment-related toxicities. The prompt and early management of these events is critically needed to reduce their impact on patient outcome and quality of life (QoL) to optimize medical resource utilization. Therefore, physicians and patients should be aware of these risks when managing the use of these VEGFR-TKIs in STS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Scientific Foundation of China (No. 81372887), the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2013CB910500) and the National Scientific Foundation of China (No. 81572403).

Supplementary materials

Table S1 Nine-point NOS scores for the NRCTs

Table S2 Risk of bias in RCTs

Table S3 The clinical therapeutic effects of the included studies

References

- SleijferSRay-CoquardIPapaiZPazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (EORTC study 62043)J Clin Oncol200927193126313219451427

- YooKHKimHSLeeSJEfficacy of pazopanib monotherapy in patients who had been heavily pretreated for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective case seriesBMC Cancer20151515425885855

- MakiRGD’AdamoDRKeohanMLPhase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomasJ Clin Oncol200927193133314019451436

- von MehrenMRankinCGoldblumJRPhase 2 Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial (S0505) of sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomasCancer2012118377077621751200

- Ray-CoquardIItalianoABompasESorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II Trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO)Oncologist201217226026622285963

- SantoroAComandoneABassoUPhase II prospective study with sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas after anthracycline-based therapyAnn Oncol20132441093109823230134

- BramswigKPlonerFMartelASorafenib in advanced, heavily pretreated patients with soft tissue sarcomasAnticancer Drugs201425784885324667659

- GeorgeSMerriamPMakiRGMulticenter phase II trial of sunitinib in the treatment of nongastrointestinal stromal tumor sarcomasJ Clin Oncol200927193154316019451429

- LiTWangLWangHA retrospective analysis of 14 consecutive Chinese patients with unresectable or metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma treated with sunitinibInvest New Drugs201634670170627604635

- van der GraafWTBlayJYChawlaSPPazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trialLancet201237998291879188622595799

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ClarkMAFisherCJudsonIThomasJMSoft-tissue sarcomas in adultsN Engl J Med2005353770171116107623

- CasaliPGBlayJYExperts ECECPoSoft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201021suppl 5v198v20320555081

- DaigelerAZmarslyIHirschTLong-term outcome after local recurrence of soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of factors predictive of survival in 135 patients with locally recurrent soft tissue sarcomaBr J Cancer201411061456146424481401

- WeitzJAntonescuCRBrennanMFLocalized extremity soft tissue sarcoma: improved knowledge with unchanged survival over timeJ Clin Oncol200321142719272512860950

- SleijferSOualiMvan GlabbekeMPrognostic and predictive factors for outcome to first-line ifosfamide-containing chemotherapy for adult patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: an exploratory, retrospective analysis on large series from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (EORTC-STBSG)Eur J Cancer2010461728319853437

- CudmoreMJHewettPWAhmadSThe role of heterodimerization between VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in the regulation of endothelial cell homeostasisNat Commun2012397222828632

- IvySPWickJYKaufmanBMAn overview of small-molecule inhibitors of VEGFR signalingNat Rev Clin Oncol200961056957919736552

- HDAC Inhibition Overcomes Resistance to VEGFR inhibitors in solid tumorsCancer Discov201774350

- SchutzFAChoueiriTKSternbergCNPazopanib: clinical development of a potent anti-angiogenic drugCrit Rev Oncol Hematol201177316317120456972

- van der GraafWTBlayJYChawlaSPPazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trialLancet201237998291879188622595799

- SleijferSRay-CoquardIPapaiZPazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (EORTC study 62043)J Clin Oncol200927193126313219451427

- Medscape [homepage on the Internet]FDA Approves Votrient for Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcoma2018 Available from: http://www.fda.govAccessed April 24, 2018

- MakiRGD’AdamoDRKeohanMLPhase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomasJ Clin Oncol200927193133314019451436

- StrumbergDRichlyHHilgerRAPhase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumorsJ Clin Oncol200523596597215613696

- JhanwarSCChenQLiFPBrennanMFWoodruffJMCytogenetic analysis of soft tissue sarcomas. Recurrent chromosome abnormalities in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST)Cancer Genet Cytogenet19947821381447828144

- JohnsonMRDeClueJEFelzmannSNeurofibromin can inhibit Ras-dependent growth by a mechanism independent of its GTPase-accelerating functionMol Cell Biol19941416416458264632

- MoriSSatohTKoideHNakafukuMVillafrancaEKaziroYInhibition of Ras/Raf interaction by anti-oncogenic mutants of neurofibromin, the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene product, in cell-free systemsJ Biol Chem19952704828834288387499408

- KeirSTMarisJMLockRInitial testing (stage 1) of the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor sorafenib by the pediatric preclinical testing programPediatr Blood Cancer20105561126113320672370

- MarisJMCourtrightJHoughtonPJInitial testing (stage 1) of sunitinib by the pediatric preclinical testing programPediatr Blood Cancer2008511424818293383

- KeirSTMortonCLWuJKurmashevaRTHoughtonPJSmithMAInitial testing of the multitargeted kinase inhibitor pazopanib by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing ProgramPediatr Blood Cancer201259358658822190407

- ChowLQEckhardtSGSunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacyJ Clin Oncol200725788489617327610

- MahmoodSTAgrestaSVigilCEPhase II study of sunitinib malate, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with relapsed or refractory soft tissue sarcomas. Focus on three prevalent histologies: leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytomaInt J Cancer201112981963196921154746

- StacchiottiSNegriTLibertiniMSunitinib malate in solitary fibrous tumor (SFT)Ann Oncol201223123171317922711763

- StacchiottiSNegriTZaffaroniNSunitinib in advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma: evidence of a direct antitumor effectAnn Oncol20112271682169021242589

- DemetriGDvan OosteromATGarrettCREfficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trialLancet200636895441329133817046465

- EscudierBEisenTStadlerWMSorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinomaN Engl J Med2007356212513417215530

- LlovetJMRicciSMazzaferroVSorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinomaN Engl J Med2008359437839018650514

- SternbergCNDavisIDMardiakJPazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trialJ Clin Oncol20102861061106820100962

- RaymondEDahanLRaoulJLSunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumorsN Engl J Med2011364650151321306237

- RyanJLCarrollJKRyanEPMustianKMFiscellaKMorrowGRMechanisms of cancer-related fatigueOncologist200712suppl 12234

- HensleyMLSillMWScribnerDRJrSunitinib malate in the treatment of recurrent or persistent uterine leiomyosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group phase II studyGynecol Oncol2009115346046519811811

- HigginsJPAltmanDGGotzschePCThe Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trialsBMJ2011343d592822008217

- YooKHKimHSLeeSJEfficacy of pazopanib monotherapy in patients who had been heavily pretreated for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective case seriesBMC Cancer20151515425885855

- von MehrenMRankinCGoldblumJRPhase 2 Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial (S0505) of sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomasCancer2012118377077621751200

- Ray-CoquardIItalianoABompasESorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II Trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO)Oncologist201217226026622285963

- SantoroAComandoneABassoUPhase II prospective study with sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas after anthracycline-based therapyAnn Oncol20132441093109823230134

- BramswigKPlonerFMartelASorafenib in advanced, heavily pretreated patients with soft tissue sarcomasAnticancer Drugs201425784885324667659

- GeorgeSMerriamPMakiRGMulticenter phase II trial of sunitinib in the treatment of nongastrointestinal stromal tumor sarcomasJ Clin Oncol200927193154316019451429

- LiTWangLWangHA retrospective analysis of 14 consecutive Chinese patients with unresectable or metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma treated with sunitinibInvest New Drugs201634670170627604635

- LiuBDingFZhangDWeiGHRisk of venous and arterial thromboembolic events associated with VEGFR-TKIs: a meta-analysisCancer Chemother Pharmacol201780348749528695268

- MasseyPROkmanJSWilkersonJCowenEWTyrosine kinase inhibitors directed against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) have distinct cutaneous toxicity profiles: a meta-analysis and review of the literatureSupport Care Cancer20152361827183525471178

- EscudierBPortaCBonoPRandomized, controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial assessing treatment preference for pazopanib versus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: PISCES StudyJ Clin Oncol201432141412141824687826

- SantoniMContiAMassariFTreatment-related fatigue with sorafenib, sunitinib and pazopanib in patients with advanced solid tumors: an up-to-date review and meta-analysis of clinical trialsInt J Cancer2015136111024415642

- CroomKFPerryCMImatinib mesylate: in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumoursDrugs2003635513522 discussion 523–51412600228

- RutkowskiPWozniakASwitajTAdvances in molecular characterization and targeted therapy in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberansSarcoma2011201195913221559214

- RutkowskiPVan GlabbekeMRankinCJImatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trialsJ Clin Oncol201028101772177920194851

- KerobDPorcherRVerolaOImatinib mesylate as a preoperative therapy in dermatofibrosarcoma: results of a multicenter phase II study on 25 patientsClin Cancer Res201016123288329520439456

- StacchiottiSPedeutourFNegriTDermatofibrosarcoma protuberans-derived fibrosarcoma: clinical history, biological profile and sensitivity to imatinibInt J Cancer201112971761177221128251