Abstract

Background

Occult breast cancer (OBC) is a rare type of breast cancer that has not been well studied. The clinicopathological characteristics and treatment recommendations for OBC are based on a limited number of retrospective studies and thus remain controversial.

Patients and methods

We identified 479 OBC patients and 115,739 non-OBC patients from 2004 to 2014 in and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes were compared between OBC and non-OBC patients. We used the propensity score 1:1 matching analysis to evaluate OBC vs non-OBC comparison using balanced groups with respect to the observed covariates. We further divided the OBC population into four groups based on different treatment strategies. Univariable and multivariable analyses were used to calculate and compare the four treatment outcomes within the OBC population.

Results

OBC patients were older, exhibited a more advanced stage, a higher rate of negative estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status, a higher rate of HER2-positive status, and a higher rate of ≥10 positive lymph nodes, and were less likely to undergo surgical treatment than non-OBC patients. After adjustments for clinicopathological factors, the OBC patients exhibited a significantly better survival than the non-OBC patients (P<0.001). This result was confirmed in a 1:1 matched case–control analysis. Within the four OBC treatment groups, we observed no difference in survival among the mastectomy group, the breast-conserving surgery (BCS) group, and the axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)-only group. The multivariable analysis revealed that the sentinel lymph node dissection-only group had the worst prognosis (P<0.001). Conclusion: OBC has unique clinicopathological characteristics and a favorable prognosis compared with non-OBC. BCS plus ALND and radiotherapy showed a survival benefit that was similar to that of mastectomy for OBC patients.

Introduction

Occult breast cancer (OBC), which manifests as axillary lymph node (LN) metastasis without the evidence of a primary breast tumor on clinical examination or mammography, accounts for 0.3%–1.0% of all breast cancers.Citation1–Citation3 Although OBC has been described as having a natural history and biological behavior similar to that of node-positive non-OBC,Citation4,Citation5 the clinicopathological characteristics of OBC, such as the hormone status, the HER2 status, and the LN involvement, are still unclear due to the rarity of this type of cancer.Citation6–Citation8 Furthermore, the survival outcomes of patients with OBC are still controversial. The 10-year overall survival (OS) rate varies from 47.5% to 67.1%.Citation7 OBC has been reported to show an outcome that was similar to or more favorable than that of stage II–III, T1N1, or small invasive breast cancers (pT1),Citation5,Citation6,Citation9–Citation11 but several studies reported an opposite conclusion.Citation12,Citation13

OBC, which is extremely uncommon, continues to present a therapeutic challenge. Previous studies suggested that breast-conserving surgery (BCS) with axillary LN dissection (ALND) plus radiotherapy (RT) resulted in a survival outcome similar to that of mastectomy plus ALND.Citation6,Citation8 However, the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with negative MRI results should be treated with mastectomy plus ALND or ALND plus whole breast irradiation.Citation14 On the contrary, systemic chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or trastuzumab is given for stage II or III disease according to the recommendations.Citation14 However, the limited number of patients included in previous retrospective studies did not give us sufficient information to determine reliable treatment recommendations.Citation15–Citation17 Furthermore, updated cohort information is needed to further our understanding of OBC and to guide oncologists in treatment selection.

Utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, we sought to obtain the most recent population-based data to 1) study the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes of OBC and 2) evaluate different treatment outcomes in OBC patients.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

Our study was approved by the independent ethical committee/institutional review board at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (Shanghai Cancer Center Ethical Committee). The data released by the SEER database are publicly available and deidentified and thus do not require patient informed consent.

Patient selection and data acquisition

We used SEER data released in November 2016, which include data from 18 population-based cancer registries (1973–2014) and cover approximately 28% of US cancer patients. The inclusion criteria used to identify eligible patients were as follows: females older than 18 years of age, breast-adjusted American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) sixth edition (1988+) stage T0-3N1-3M0, one or more positive LNs, unilateral breast cancer, breast cancer (ICD-O-3 site code C50) as the first and only cancer diagnosis, either no surgical treatment or surgical treatment with BCS or mastectomy, diagnosis not obtained from a death certificate or autopsy, only one primary site, a known number of examined LNs, and a known time of diagnosis between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2014. In all, 116,218 patients were included. Of these patients, 479 (stage T0N1-3M0) were diagnosed with OBC and 115,739 (stage T1-3N1-3M0) were diagnosed with non-OBC.

An analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics of OBC and non-OBC included the year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, race, marital status, laterality, grade, AJCC stage, AJCC N stage, estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, HER2 status, breast cancer subtype, breast surgery type, RT, number of examined LNs, and number of positive LNs. We considered the year of diagnosis as a binary variable classified into the following two groups: 2004–2009 and 2010–2014. The age at diagnosis was also considered a binary variable and was classified into the following two groups: 18–49 years and more than 50 years. For HER2 status, data were available only after 2010 due to limitations in the SEER database. Moreover, the number of examined LNs was classified into the following three groups: 1–3, 4–9, and ≥10, while the number of positive LNs was categorized into the following four groups: 1–3, 4–9, ≥10, and unknown.

Treatment course

Patients who underwent breast surgery (BCS, mastectomy, or no surgery), RT, sentinel LN dissection (SLND) and/or ALND were identified based on the SEER variables. The SEER database did not specify the type of axillary LN surgery performed; therefore, surrogate data were used to categorize patients as having undergone SLND or ALND. Patients in whom one to five LNs were examined were considered to have undergone SLND alone, whereas patients in whom more than five LNs were examined were considered to have undergone ALND. These definitions were based on the AJCC definition of a standard minimum ALND (at least six LNs).Citation18 The treatment groups of OBC population were defined according to breast surgery, LN status, and RT: 1) the mastectomy group (mastectomy plus ALND, with or without RT); 2) the BCS group (BCS plus both ALND and RT); 3) the ALND-only group; and 4) the SLND-only group.

Outcome measurement

In this study, breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS), which we used as the primary study outcome, was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from breast cancer. Patients who died from other causes unrelated to their breast cancer diagnosis and those who remained alive were cen sored on the date of death or the date of last contact. OS, the secondary outcome, was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause, and patients who were alive on the date of final follow-up were censored. The cutoff date for the study was predetermined by the submission databases; the SEER November 2016 submission databases contain complete death data through 2014. Therefore, December 31, 2014, was assigned as the cutoff date for the study.

Statistical analyses

The clinicopathological characteristics were compared across groups using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to calculate the 5-year BCSS and OS rates, and the log-rank test was used to determine differences between curves. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied to identify factors associated with survival; the HR and 95% CI were reported. To account for large sample size, we selected the variables with P<0.001 () or P<0.05 () which were significantly associated with the BCSS or OS in the univariable analysis. To account for differences in the baseline characteristics across the two breast cancer subtype groups, we matched each OBC patient to one non-OBC patient according to the following predetermined factors: age, year of diagnosis, race, grade, AJCC N stage, ER status, PR status, type of breast surgery, and use of RT. Since 1:1 matching is the most common implementation of propensity score matching and the statistical power does not decrease,Citation19 we used psmatch2 to perform a “one-to-one match” with the caliper width set as 0.05 in Stata statistical software for propensity score matching. Furthermore, patients in a matched pair have the same value of the propensity score. The stratified Cox model was conducted within matched pairs. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and a stratified log-rank test was used to compare survival curves after propensity score matching. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1 Multivariable analysis of BCSS and OS in all patients

Table 2 Multivariable analysis of BCSS and OS in OBC patients

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of OBC patients

The clinicopathological characteristics of all 116,218 selected patients are summarized in . Compared with non-OBC patients, OBC patients presented a higher proportion of stage III disease (39.87% vs 33.14%, P=0.002), N3 classification (19.62% vs 9.06%, P<0.001), ER negativity (36.54% vs 19.37%, P<0.001) and PR-negative status (52.19% vs 29.74%, P<0.001), and HER2-positive status (12.11% vs 7.87%, P<0.001). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with ≥10 examined LNs, ≥10 positive LNs, and no surgery was significantly higher in the OBC group than in the non-OBC group (68.06% vs 62.13%, P=0.001; 15.87% vs 8.37%, P<0.001; 48.85% vs 0.87%, P<0.001, respectively). RT, however, was performed with similar frequency in both groups. These data indicated that the baseline characteristics of OBC are distinct from those of non-OBC.

Table 3 Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with OBC and non-OBC

Comparison of survival between OBC and non-OBC patients

After the baseline characteristics were summarized, we further evaluated BCSS and OS in these two groups using the Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Figure S1). The 5-year BCSS rate of the OBC group was 88.02% (95% CI 84.06–91.04%), and the 5-year OS rate of the OBC group was 85.51% (95% CI 81.27–88.85%), which were similar to the rates observed in the non-OBC group. We used the Cox proportional hazards model to investigate the effect of baseline characteristics on survival outcomes. A univariable analysis revealed that the year of diagnosis, age, race, marital status, tumor grade, ER status, PR status, HER2 status, breast surgery type, RT status, and the number of positive LNs were significantly associated with the BCSS and OS (P<0.001). However, the difference between the OBC group and the non-OBC group was not statistically significant (Table S1). Furthermore, we included all variables mentioned earlier in the multivariable analysis (). However, after adjustment for potential confounders, OBC was identified as an independent protective factor for both BCSS (HR =0.37, 95% CI 0.27–0.50, P<0.001) and OS (HR =0.41, 95% CI 0.31–0.52, P<0.001).

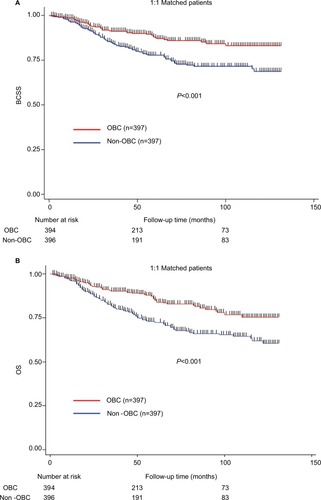

Survival analysis in matched groups

To further evaluate the detected differences between OBC and non-OBC groups, we performed a 1:1 (OBC:non-OBC) matched case–control analysis using the propensity score matching method. We defined a group of 794 patients, where 397 patients were included in each group (Table S2). For the matched groups, we found no statistically significant difference in the baseline characteristics between the OBC patients and the non-OBC patients. As expected, the OBC patients demonstrated a better prognosis in terms of both BCSS and OS (; P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively), which was consistent with the stratified Cox models (Table S3; BCSS HR =0.40, 95% CI 0.27–0.50, P<0.001; OS HR =0.41, 95% CI 0.31–0.52, P<0.001). In conclusion, OBC predicted a better prognosis than non-OBC after adjustment for clinicopathological characteristics.

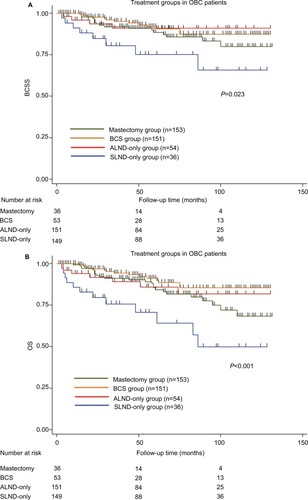

Clinical outcomes of OBC in different treatment groups

Since local treatment options for OBC are a subject of intense interest, we further evaluated the relationship between the type of surgery and survival in OBC. We classified the OBC patients into four groups based on different treatment strategies as follows: 153 (38.8%) patients were treated with mastectomy plus ALND, with or without RT; 151 (38.3%) patients were treated with BCS plus both ALND and RT; 54 (13.7%) patients received ALND only; and 36 patients (9.1%) underwent SLND only. The clinicopathological characteristics of these four treatment groups are summarized in Table S4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to evaluate the clinical outcomes in these four treatment groups (). Significant differences were observed in BCSS (P=0.023) and OS (P<0.001) between the treatment groups. Since survival was also affected by ER status, PR status, and the number of positive LNs (Table S5), we performed a multivariable analysis to adjust for these variables (). After the adjustment, the SLND-only group significantly demonstrated the worst BCSS (P<0.001) and OS (P<0.001). No differences were detected in the survival rates among the mastectomy group, the BCS group and the ALND-only group in either BCSS or OS (Table S6).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to the four groups based on different treatment strategies in OBC patients.

Notes: (A) BCSS. (B) OS. Log-rank tests were compared between groups.

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; OBC, occult breast cancer; OS, overall survival; SLND, sentinel lymph node dissection.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we investigated the clinicopathological characteristics and treatment outcomes of OBC based on a large population from the SEER database. Compared with non-OBC patients, OBC patients presented with distinct baseline characteristics and different BCSS and OS rates. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, OBC patients demonstrated a significant survival advantage over non-OBC patients. Further analyses that evaluated the treatment strategies of the OBC patients revealed that the mastectomy group, the BCS group, and the ALND-only group had comparable outcomes.

Our analysis took advantage of the SEER database to investigate the clinicopathological characteristics of the OBC cohort based on a large population size. Compared with non-OBC, this special type of breast cancer was associated with older age, a more advanced stage, a higher proportion of negative hormone receptor expression, a higher proportion of HER2-positive status, a greater likelihood of having ≥10 positive LNs, and a lower likelihood of surgical treatment; some of these associations were concordant with the findings of previous studies.Citation5,Citation10,Citation11,Citation20 The higher proportion of negative ER and PR status in OBC than in non-OBC might be explained by the discordance in this status between the primary tumor and LN metastases.Citation21,Citation22 Due to the absence of clinically, radiologically, or pathologically identifiable breast tumors, the receptor status in OBC patients was detected from the metastatic LNs. Discordance was reported to result from the following three main factors: false-positive and false-negative results in the assessment of receptor expression, the heterogeneity of receptor expression in the same tumor, and evolutionary modifications in the biology of the cancer.Citation23–Citation25 These baseline characteristics reveal that we cannot regard this rare disease in the same manner as palpable breast cancers.

Our study demonstrated that OBC patients showed higher survival rates than non-OBC patients. Furthermore, the 1:1 matching study confirmed this result. Collectively, these survival advantages suggest that OBC has a relatively benign biological behavior even though it initially presents as axillary LN metastasis, a concept that runs counter to our understanding of locally metastatic breast cancer.Citation26,Citation27 Pentheroudakis et alCitation5 reported that OBC grew more indolent than overt breast cancer, which is an observation that adds evidence to our conclusion.

Treatment strategies for OBC have varied over the years, and to date, no definite consensus has been reached. Mastectomy with ALND, a regimen that was first described by Halsted,Citation28 has traditionally been believed to provide the most effective local treatment for OBC patients. The advantage of mastectomy for OBC treatment is that it can confirm the diagnosis of OBC after a detailed pathological examination,Citation29 despite that no primary tumor was found in 30%–60% of patients.Citation1,Citation30–Citation32 In recent years, published studies have demonstrated that mastectomy did not improve survival outcomes compared with BCS in OBC patients and that BCS plus ALND with RT is an acceptable alternative.Citation8,Citation29,Citation33–Citation37 Consistent with these studies, we observed similar BCSS and OS outcomes in the BCS group and in the mastectomy group. He et alCitation8 also observed similar locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS) and recurrence/metastasis-free survival (RFS) outcomes between these two treatment groups in a retrospective study that assessed patients from 1998 to 2010. Our study provides additional evidence that BCS plus both ALND and RT instead of mastectomy with or without RT might be a favorable management strategy for OBC patients. However, in this study, the ALND-only group exhibited BCSS and OS rates similar to those of the BCS group and the mastectomy group, a result that was different from the majority of the published literature.Citation7,Citation20,Citation34,Citation35,Citation38,Citation39 Only one study, conducted in Korea, supported our finding, with the explanation that the ALND-only group in their study population had a high prevalence of stage N3 disease.Citation6 In our study, potential explanations for this observation are that the ALND-only group included a limited number of patients (n=54) and had a higher proportion of patients with 1–3 positive LNs (57.41%, P=0.003). In addition, defining ALND by different criteria may affect the survival outcomes. Other SEER database analyses categorized more than three examined LNs as having undergone ALND;Citation7,Citation40 this definition was inconsistent with our definition of ALND as the examination of more than five LNs. Therefore, further clinical studies are needed to evaluate this controversial conclusion and to confirm that ALND is an effective standalone treatment strategy for OBC patients. Moreover, our analysis found that the SLND-only group had the worst survival rate, which suggests that the extent of LN examination and the type of locoregional therapy are important for OBC patients.Citation7,Citation20,Citation41

The advantage of this study is that it is based on a database that to the best of our knowledge includes the largest patient population in the world. Inevitably, the current study still has several limitations. First, this study was a retrospective cohort study and might have some potential selection biases and weaknesses. Second, the incidence of locoregional recurrence is not captured in the SEER data; this omission limits our survival analysis of OBC patients. Third, records of adjuvant systemic therapy such as endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, and chemotherapy are not included in the SEER database. It is widely accepted that systemic therapy is commonly used in patients with node-positive breast cancer.Citation5,Citation42 These missing data, therefore, may weaken our conclusion. Large, population-based, multi-institutional analyses should be conducted to further validate these findings.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that OBC has unique clinicopathological characteristics compared with non-OBC. Although OBC patients showed a prognosis similar to that of the overall non-OBC population, their survival was significantly increased after adjustment for confounders. We did not observe a difference in outcomes among the mastectomy group, the BCS group, and the ALND-only group. However, there is insufficient evidence to support ALND alone as an effective treatment strategy. A thorough biological and clinical understanding of OBC might improve the clinical management of and the outcomes of this rare type of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502278, 81572583, 81372848, 81370075), the Training Plan of Excellent Talents in the Shanghai Municipality Health System (2017YQ038), the Training Plan of Excellent Talents of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (YJYQ201602), the Municipal Project for Developing Emerging and Frontier Technology in Shanghai Hospitals (SHDC12010116), the Cooperation Project of Conquering Major Diseases in the Shanghai Municipality Health System (2013ZYJB0302), the Innovation Team of the Ministry of Education (IRT1223), and the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Breast Cancer (12DZ2260100). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Y-ZJ and G-HD designed the experiments. L-PG and X-YL performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Y-ZJ, YX, Z-CG, and SZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PatelJNemotoTRosnerDDaoTLPickrenJWAxillary lymph node metastasis from an occult breast cancerCancer19814712292329277260879

- RosenPPAxillary lymph node metastases in patients with occult noninvasive breast carcinomaCancer1980465129813066260331

- OwenHWDockertyMBGrayHKOccult carcinoma of the breastSurg Gynecol Obstet195498330230813146478

- PavlidisNPentheroudakisGCancer of unknown primary siteLancet201237998241428143522414598

- PentheroudakisGLazaridisGPavlidisNAxillary nodal metastases from carcinoma of unknown primary (CUPAx): a systematic review of published evidenceBreast Cancer Res Treat2010119111119771506

- SohnGSonBHLeeSJTreatment and survival of patients with occult breast cancer with axillary lymph node metastasis: a nationwide retrospective studyJ Surg Oncol2014110327027424863883

- WalkerGVSmithGLPerkinsGHPopulation-based analysis of occult primary breast cancer with axillary lymph node metastasisCancer2010116174000400620564117

- HeMTangLCYuKDKdYTreatment outcomes and unfavorable prognostic factors in patients with occult breast cancerEur J Surg Oncol201238111022102822959166

- RosenPPKimmelMOccult breast carcinoma presenting with axillary lymph node metastases: a follow-up study of 48 patientsHum Pathol19902155185232338331

- MontagnaEBagnardiVRotmenszNImmunohistochemically defined subtypes and outcome in occult breast carcinoma with axillary presentationBreast Cancer Res Treat2011129386787521822638

- PingSMingWHBinSHComparison of clinical characteristics between occult and non-occult breast cancerJ Buon201419366266625261649

- JacksonBScott-ConnerCMoulderJAxillary metastasis from occult breast carcinoma: diagnosis and managementAm Surg19956154314347733550

- SvasticsERónayPBodóMOccult breast cancer presenting with axillary metastasisEur J Surg Oncol19931965755808270047

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Breast Cancer v3.20172017

- BlanchardDKShettyPBHilsenbeckSGElledgeRMAssociation of surgery with improved survival in stage IV breast cancer patientsAnn Surg2008247573273818438108

- OlsonJAMorrisEAvan ZeeKJLinehanDCBorgenPIMagnetic resonance imaging facilitates breast conservation for occult breast cancerAnn Surg Oncol20007641141510894136

- VaradarajanREdgeSBYuJWatrobaNJanarthananBRPrognosis of occult breast carcinoma presenting as isolated axillary nodal metastasisOncology2006715–645645917690561

- StephenBEByrdDRMichaelAM AJCC Cancer Staging Manual7th edNew YorkSpringer2010

- AustinPCStatistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-one matching on the propensity scoreAm J Epidemiol201017291092109720802241

- HesslerLKMolitorisJKRosenblattPYFactors Influencing Management and Outcome in Patients with Occult Breast Cancer with Axillary Lymph Node Involvement: Analysis of the National Cancer DatabaseAnn Surg Oncol201724102907291428766198

- AmirEMillerNGeddieWProspective study evaluating the impact of tissue confirmation of metastatic disease in patients with breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201230658759222124102

- LindströmLSKarlssonEWilkingUMClinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progressionJ Clin Oncol201230212601260822711854

- PusztaiLVialeGKellyCMHudisCAEstrogenHCAEstrogen and HER-2 receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and metastasisOncologist201015111164116821041379

- KhasrawMBrogiESeidmanADThe need to examine metastatic tissue at the time of progression of breast cancer: is re-biopsy a necessity or a luxury?Curr Oncol Rep2011131172521053108

- CurtitENerichVMansiLDiscordances in estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, and HER2 status between primary breast cancer and metastasisOncologist201318666767423723333

- PentheroudakisGBriasoulisEPavlidisNCancer of unknown primary site: missing primary or missing biology?Oncologist200712441842517470684

- PavlidisNBriasoulisEHainsworthJGrecoFADiagnostic and therapeutic management of cancer of an unknown primaryEur J Cancer200339141990200512957453

- HalstedWSIThe Results of Radical Operations for the Cure of Carcinoma of the BreastAnn Surg1907461119

- WangXZhaoYCaoXClinical benefits of mastectomy on treatment of occult breast carcinoma presenting axillary metastasesBreast J2010161323720465598

- MersonMAndreolaSGalimbertiVBufalinoRMarchiniSVeronesiUBreast carcinoma presenting as axillary metastases without evidence of a primary tumorCancer19927025045081617600

- AbbruzzeseJLAbbruzzeseMCLenziRHessKRRaberMNAnalysis of a diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected tumors of unknown originJ Clin Oncol1995138209421037636553

- KemenyMMRiveraDETerzJJBenfieldJROccult primary adenocarcinoma with axillary metastasesAm J Surg1986152143473728816

- BartonSRSmithIEKirbyAMAshleySWalshGPartonMThe role of ipsilateral breast radiotherapy in management of occult primary breast cancer presenting as axillary lymphadenopathyEur J Cancer201147142099210621658935

- ShannonCWalshGSapunarFA’HernRSmithIOccult primary breast carcinoma presenting as axillary lymphadenopathyBreast200211541441814965705

- ForoudiFTiverKWOccult breast carcinoma presenting as axillary metastasesInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200047114314710758316

- BlanchardDKFarleyDRRetrospective study of women presenting with axillary metastases from occult breast carcinomaWorld J Surg200428653553915366740

- RuethNMBlackDMLimmerARBreast conservation in the setting of contemporary multimodality treatment provides excellent outcomes for patients with occult primary breast cancerAnn Surg Oncol2015221909525249256

- CampanaFFourquetAAshbyMAPresentation of axillary lymphadenopathy without detectable breast primary (T0 N1b breast cancer): experience at Institut CurieRadiother Oncol19891543213252552505

- EllerbroekNHolmesFSingletaryEEvansHOswaldMMcneeseMTreatment of patients with isolated axillary nodal metastases from an occult primary carcinoma consistent with breast originCancer1990667146114672207996

- KimBHKwonJKimKEvaluation of the Benefit of Radiotherapy in Patients with Occult Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis of the SEER DatabaseCancer Res Treat201850255156128602055

- MacedoFIEidJJFlynnJJacobsMJMittalVKOptimal Surgical Management for Occult Breast Carcinoma: A Meta-analysisAnn Surg Oncol20162361838184426832884

- CuriglianoGBursteinHJP WinerEPwEDe-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017Ann Oncol20172881700171228838210