Abstract

Background

Primary bone marrow lymphoma (PBML) is a very uncommon neoplasm originally arising in the bone marrow system, and the most common pathological type is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Patients and methods

To describe the clinical characteristics of PBML and evaluate the risk factors related to prognosis, we recruited and studied 66 patients from our center and the current published literature. Various symptoms are present at the onset of PBML, the most important of which is cytopenia, followed by fever. Forty-seven of these patients were included in our analysis.

Results

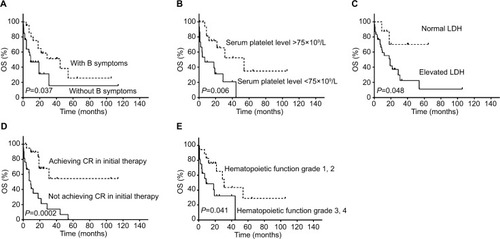

Univariate analysis suggested that B symptoms (P=0.024), a low serum platelet level (<75×109/L; P=0.032), an elevated serum LDH level (P=0.039), and not achieving a complete response (CR) following initial therapy (P=0.007) are associated with worse outcomes. Multivariate analysis showed that only a low serum platelet level (<75×109/L), B symptoms, and not achieving a CR following initial therapy are independent factors for prognosis. In addition, intensive regimens appear to be beneficial for prognosis.

Conclusion

PBML is a lymphoma with special clinical features, and its recognition is important for establishing a definitive prognosis model and searching for appropriate therapy.

Background

Primary bone marrow lymphoma (PBML) is an extremely rare form of lymphoma with rapid disease progression and a poor prognosis.Citation1,Citation2 A previous case series study conducted by Martinez et alCitation1 focused on the pathological features of PBML; however, only a few clinical features were found to be associated with the disease. Five different pathological types of lymphoma can originate in the bone marrow, including Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified lymphoma (PTCL, NOS), ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALK-negative ALCL), and follicular lymphoma (FL).Citation1 Among these types, DLBCL is the most common pathological subtype. However, due to the low incidence of the disease, large-scale and systematic case series studies are lacking; therefore, information regarding the clinical features of PBML is lacking. Additionally, the current treatments for PBML are not uniform and have not been standardized, and most treatments focus on only the pathological type and lack specificity and scientific evidence. Furthermore, no study has reported the risk factors affecting the outcomes of PBML. Thus, we reviewed some cases that had been diagnosed at our single center and analyzed previous studies. The present study aimed to investigate the specific clinical features and risk stratification effects on the outcomes of these patients and to discuss treatment strategies for PBML.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and data collection

The following criteria were used to define PBML: 1) pathologically confirmed bone marrow involvement, regardless of peripheral blood involvement; 2) absence of lymph node, spleen, liver, or other extra marrow involvement upon physical examination or imaging studies (including thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic enhanced computerized tomography [CT], systemic superficial lymph node B-scan ultrasonography, and systemic positron emission tomography/CT [PET/ CT]; among these imaging studies, PET/CT is considered relatively authoritative); 3) no evidence of localized bone tumors; 4) bone marrow biopsy with no signs of bony trabecular destruction or PET/CT revealing diffuse enhanced bone marrow metabolism without a localized bone lesion; and 5) exclusion of leukemia/lymphoma cases, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, prolymphocytic leukemia, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia, Burkitt lymphoma (Burkitt leukemia variant), and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.Citation1

In addition to the above mentioned diagnostic criteria, we added the following exclusion criteria: 1) cases with a second tumor or a disease that could seriously influence survival and 2) B-cell lymphomas that could not be further diagnosed.

All patients’ clinical data, including sex, age, initial symptoms, peripheral blood indicators at first admission, LDH level, β-2 microglobulin level, international prognostic index, treatment modality, treatment response, and radiological findings, were collected. The bone marrow examination included a bone marrow smear cytologic examination, bone marrow biopsy, and bone marrow aspiration.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for the collection of medical information was obtained from all patients. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Statistical analysis

Complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease were used to define the classification of the treatment response according to the criteria for malignant lymphoma. The overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of pathological diagnosis to death or to the last date of follow-up. We divided the degree of cytopenia into the following four levels: Grade 0: leukocytes ≥4.0×109/L, hemoglobin ≥110 g/L, platelets ≥100×109/L; Grade 1: leukocytes (3.0–3.9)×109/L, hemoglobin (95–100) g/L, platelets (75–99)×109/L; Grade 2: leukocytes (2.0–2.9)×109/L, hemoglobin (80–94) g/L, platelets (50–74)×109/L; Grade 3: leukocytes (1.0–1.9)×109/L, hemoglobin (65–79) g/L, platelets (25–49)×109/L; and Grade 4: leukocytes (0–1.0)×109/L, hemoglobin <65 g/L, platelets <25×109/L. OS and survival curves were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method. The survival of patients with different prognostic variables was analyzed by the log-rank test, and multiple independent prognostic factors were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. The correlations between two variables were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-square analysis. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0.

Results

Patient characteristics in our center

Seven patients with PBML who were treated at the Lymphoma Diagnosis and Treatment Center of Henan Province were enrolled between July 2011 and June 2017 into this study; their clinical characteristics are listed in . The median follow-up time was 10.4 months (range: 1.0–25 months) and the median age at diagnosis was 56 years (range: 38–72 years). There were five deaths, accounting for 71.4%. Of these patients, three patients died from treatment failure and other two patients finally succumbed to recurrence of the disease. Notably, PET/CT was used in four cases, and all cases revealed disseminated bone marrow with diffuse hypermetabolism, and the median standard uptake value level was 5.9 (range: 4.8–7.5).

Table 1 Clinical features of seven patients with PBML in our center

Literature review and statistical analysis

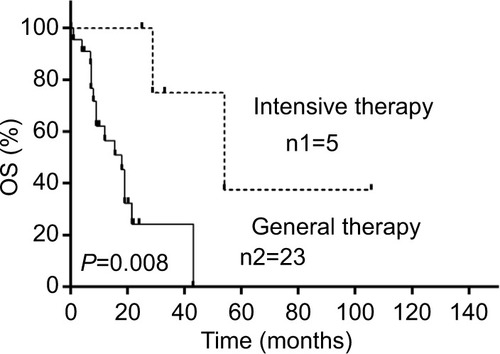

Data of 66 cases of PBML were collected and analyzed as follows: 7 cases were among the cases at our center and 59 cases were identified through searching PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang Data from 1997 to 2018, and the specific information of these patients is presented in . Nineteen of them were excluded due to lack of specific follow-up time; finally, 47 cases were enrolled into this retrospective analysis. As shown in , the female/male ratio of the patients was 4:7 (24:42), and the age ranged between 29 and 81 years (median: 60.0 years; average: 57.6 years). PBML occurred in various pathological types of lymphoma. The most common PBMLs were DLB-CLs with 40 cases (60.6%). The other types included HL (14/66, 21.2%), PTCL, NOS (3/66, 4.5%), ALK-negative ALCL (2/66, 3.0%), and FL (5/66, 7.6%). Six patients with PBML had hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) at the same time, and the mean survival time was only 4 months. No examples of successful treatment were found in our study. Additionally, four patients had complicated cold agglutinin disease, and these patients usually present with cytopenia accompanied by elevated serum cold agglutinin levels. Finally, three patients were still alive and only one patient died from relapse 19 months after the initial chemotherapy. Of all the 40 cases of DLBCL, we obtained the immunohistochemical results of 39 patients, and these results are shown in . Thirty-three patients died during follow-up, including 20 patients who died from disease progression and 10 patients who died from chemotherapy-related complications. Additionally, 29/57 patients achieved CR, 9/57 patients achieved PR after initial therapy, and the overall response rate was 67.7% (50.9% CR +15.8% PR). PBML of different pathological types showed distinct prognoses. Most patients with HL were treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblas-tine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) or ABVD-like regimens. The median survival period was 4 months, and HIV-negative HL had a poorer OS than HIV-positive HL (P=0.097). However, statistically significant indicators related to prognosis could not be obtained due to insufficient data. The treatment strategies and survival time of the T-cell lymphoma patients were diverse. The median survival period was 9.6 months. Among four out of five patients with FL, only one patient died. Most patients with DLBCL were treated with cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) or a CHOP-like regimen. The median survival period was 19 months. The clinical features of 47 patients included in the retrospective analysis are summarized in . The median OS was 19 months. In the univariable analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used to analyze the influence of the following factors on survival: sex, age, degree of cytopenia, serum hemoglobin level, serum leukocyte level, serum platelet level, B symptoms, serum LDH level, serum β2-microglobulin level, and response to initial treatment; the degree of cytopenia, serum platelet level, B symptoms, serum LDH level, and response to initial treatment were found to be significantly correlated with OS (P<0.05; ), and the survival curves are shown in . Additionally, we attempted to identify the difference in prognosis between HL and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and between T-cell and B-cell lymphoma; both results were not statistically significant. Due to the limited number of cases, only those factors with P-values <0.05 were studied, including the serum LDH level, B symptoms, serum platelet level, degree of cytopenia, response to initial therapy, and degree of cytopenia* serum platelet level (which is defined as the interaction of two variables), and the results showed that there was an interaction between the two variables. Considering the P-value of the univariable analysis and clinical convenience, we excluded the variable of degree of cytopenia from the Cox regression model. Finally, the LDH level, B symptoms, serum platelet level, and response to initial therapy were included in the Cox regression analysis, and a low serum platelet level, B symptom, and not achieving CR following the initial therapy showed an independent association with an unfavorable OS (). In addition, because of the uniformity of the treatment options for DLBCL, we divided the patients into two groups: one group included 23 cases with RCHOP, RCHOP-like/CHOP, or CHOP-like regimens and the other group included 5 cases with intensive regimens, including HVPERCAVD, EPOCH, ALL, HD-CHOP, and VACOPB. The patients who had received intensive regimens showed a better OS (P=0.01; ).

Figure 1 Univariable analyses of prognostic factors for OS for our 66 patients with PBML.

Notes: (A) Kaplan meier of OS in two groups with and without B symptoms. (B) Kaplan meier of OS in two groups with serum platelet level >75×109/L and with serum platelet level <75x109/L; (C) Kaplan meier of OS in two groups with normal LDH and with elevated LDH; (D) Kaplan meier of OS in two groups achieving CR and not achieving CR in the initial therapy; (E) Kaplan meier of OS in two groups with hematopoietic function grade 1,2 and hematopoietic function grade 3,4.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; OS, overall survival; PBML, primary bone marrow lymphoma.

Figure 2 Curve of cumulative survival of patients with PBML diagnosed as DLBCL with general therapy or with intensive therapy.

Notes: n1 represents the initial number of recipients of the intensive therapy; n2 represents the initial number of recipients of the general therapy.

Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; OS, overall survival; PBML, primary bone marrow lymphoma.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of 66 patients with PBML from literature (cases 1–66)

Table 3 Pathological, phenotypic, and molecular features of DLBCL cases (n=34)

Table 4 Clinical characteristics of 47 patients with PBML

Table 5 Univariate and multivariate analyses for overall survival

Discussion

The present study is the largest study concerning PBML to date. To the best of our knowledge, regarding the clinical features and prognosis of primary marrow bone lymphoma, we are the first to perform a systematic and comprehensive review and establish a prognostic model of PBML. PBML has been sporadically reported in the literature since the 1970s. Compared with other lymphomas of the same pathological type, PBML is usually difficult to diagnose, progresses rapidly, and is easy to combine with multiple complications, such as severe infection and HLH, only part of people in the conventional treatment respond well, and OS is relatively short.Citation1–Citation3 In some cases, a clear diagnosis lacks complete evidence, and often, primary bone lymphoma (PBL) cases, which occur infrequently, are misdiagnosed as PBMLs. Most clinical manifestations of PBLs include bone pain and fractures; most of the common lesion features are destructive through localized radiological examination; and the disease often presents with a local single lesion.Citation1,Citation4 In contrast to PBL, the important symptoms of PBML include cytopenia and B symptoms, and the occurrence of bone pain is relatively rare based on our data. Additionally, in our study, the lesion was usually confined to the marrow cavity during the early stage, and the PET/CT results of 13 patients, not only from our center but also from the literature review, all presented diffuse abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the bone marrow that appeared to be more intense in the axial bones; therefore, we believe that PET/CT has a certain importance in the diagnosis of PBML, and so, we added this item to the criteria proposed by Martinez et alCitation1 in 2012. In addition, MRI usually reveals a diffusely abnormal marrow signal (low on T1-weighted images, high on T2-weighted images) in the bone marrow cavity.Citation5 Thus, imaging data can provide important information for the identification of PBL and PBML.

In our studies, three clinical variables were proved to be independent prognostic factors, including B symptoms, serum platelet levels, and response to initial treatment. In several studies about lymphoma, B symptoms have been found to be an important prognostic variable for OS.Citation6–Citation8 The degree of cytopenia is clearly closely related to disease severity. Therefore, cytopenia likely affects prognosis. However, our results indicate that platelet count was also an independent factor affecting prognosis. In fact, based on our data, thrombocytopenia does not affect treatment or increase the number of bleeding events. Some early studiesCitation9–Citation11 have revealed that thrombocytopenia affects the survival results in lymphomas with bone marrow involvement, including PBML. In addition, a similar prognostic result was reported in early-stage B-cell gastric lymphomaCitation12 and DLBCL.Citation13,Citation14 We believe that autoimmune thrombocytopenia-associated PBML may be a potential cause because autoimmune-induced thrombocytopenia predicted relapse in one-third of lymphoma patients in a study.Citation15 Age, which is a classic risk factor, was no longer associated with the OS in our study. In some conventional studies, older age-associated poor prognosis may be caused by the following three potential factors: multiple comorbidity, lower tolerance to therapy, and multiple organ dysfunction, including bone marrow function.Citation16,Citation17 However, our study indicated that the incidence of complications was nearly equal between the older age group and the younger age group. Additionally, PBML is a disease that severely influences and impairs various organ functions, especially bone marrow function, thereby reducing chemotherapy tolerance. Thus, age seems to be less important than disease malignancy.

Compared with the data from literature review, the incidence of T-cell lymphoma in our center is relatively higher, and the data showed that OS seems to be shorter, which may be associated with a higher rate of B symptoms and HLH. Lymphoma-associated HLH is a relatively vicious disease associated with the uncontrolled activation of the normal immune system,Citation18,Citation19 and another important reason is that only two people achieved CR after initial treatment.

Patients with leukopenia or thrombocytopenia were all administered granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) or recombinant human thrombopoietin, but without success. Hammerstrøm reported that three patients with neutropenia secondary to lymphoid bone marrow involvement responded well to G-CSF before chemotherapy.Citation20 However, we found no other literature confirming this problem. Based on our single-center experience, G-CSF or recombinant human thrombopoietin treatment for cytopenia involving or originating in the bone marrow is usually ineffective.

Most patients with HL were treated with ABVD or an ABVD-like regimen. Unfortunately, more than half of these patients died in the short term, and disease progression was the dominant cause of death. Morita et alCitation21 reported that HIV-negative cases tended to progress rapidly and resulted in worse outcomes, which is consistent with our analysis. Regarding T-cell lymphoma, we first used the gemcitabine, cisplatin, prednisone, and thalidomide regimen in our patients because this regimen was proven to be more efficient than CHOP for the treatment of PTCL in a prospective, randomized, controlled, and open-label clinical trial;Citation22 however, the results were not satisfactory and the results of the CHOP regimen were also not satisfactory. Some reports had mentioned that lymphomas, especially T-cell lymphomas, were the main cause of secondary HLH and were associated with a poorer prognosis.Citation23,Citation24 This condition also appeared in PBML. Among the patients with primary bone marrow T-cell lymphomas, two out of seven (28.6%) patients had HLH complications and died within a month. The clinical use of decitabine in T-cell PBML is a ground-breaking initiative, and the result that patients had increased long-term survival is also promising. Among all PBML cases, the FL cases seemed to show the mildest symptoms and best prognosis, likely due to the slow development of the disease itself. Martinez et al reported a patient who had leukocytosis as the only abnormal indicator at the time of onset and survived for >5 years until the end of follow-up. In the past two decades, most reported PBMLs have been DLBCLs. Regarding treatment, CHOP or the CHOP-like regimen was usually used as the first-line regimen, and only a small subset of patients (two cases) died from chemotherapy-related side effects during the initial therapy; our results showed that intensive regimens seem to be more effective. We suggest that this effectiveness might be because continuous low concentrations of drugs increased the effectiveness of killing aggressive cancer cells and decreased MDR-1–mediated resistance.Citation25–Citation28 Additionally, in some studies investigating aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with high-risk factors, the patients who received intensive chemotherapies actually showed a better OS than those treated with CHOP.Citation29,Citation30 In addition, some studies have published the following results in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with bone marrow infiltration: the response rate, OS, and progression-free survival of patients treated with intensive regimens were significantly higher than those of patients treated with the standard CHOP regimen.Citation11,Citation31 In conclusion, we believe that intensive therapy may indeed be conducive to survival in PBML. However, another problem that cannot be ignored is that intensive treatment may lead to greater risks in PBML than other high-risk non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Thus, safety and chemotherapy tolerance require extensive data, and the CHOP or CHOP-like regimen remains a relatively safe and moderate regimen. Kazama et alCitation32 reported that a patient who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation (Auto-SCT) after eight cycles of RCHOP survived for >7 years, representing another clinically significant therapeutic initiative illustrating the possibility that Auto-SCT can improve prognosis. Five cases (case 35, case 39, case 55, case 57, and case 59) developed central nervous system involvement during follow-up, and case 59 developed neurological lesions despite intrathecal prophylaxis, indicating not only that intrathecal treatment is necessary, but also that more valuable therapeutic measures need to be investigated to prevent intracranial progression.

This study had some limitations. First, although we expanded the sample size by reviewing the literature, this study was still a relatively small-scale study, which might have influenced the accuracy of our results. Second, some data were missing in this retrospective study. Third, this study involved less discussion and analysis of target molecules, pathology, and biology.

Conclusion

PBML is a type of lymphoma with a relatively poor prognosis compared to other lymphomas. Patients usually have poor general condition at the time of onset and a poor tolerance to initial chemotherapy during the acute phase. The survival period is generally short. B symptoms, a low serum platelet level (<75×109/L), and not achieving CR following initial therapy are unfavorable prognosis factors. Additionally, some intensive regimens that differ from traditional regimens or Auto-SCT are worth considering and further exploring. Furthermore, additional and larger prospective multicenter studies are required in the future.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570203). Gangjian Wang and Yu Chang share first authorship.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MartinezAPonzoniMAgostinelliCPrimary bone marrow lymphoma: an uncommon extranodal presentation of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomasAm J Surg Pathol201236229630422251943

- BhagatPSachdevaMUSharmaPPrimary bone marrow lymphoma is a rare neoplasm with poor outcome: case series from single tertiary care centre and review of literatureHematol Oncol2016341424825407700

- YamashitaTIshidaMMoroHPrimary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma accompanying cold agglutinin disease: a case report with review of the literatureOncol Lett201471798124348825

- LiuYThe role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in staging and restaging primary bone lymphomaNucl Med Commun201738431932428225435

- MatthiesASchusterSJAlaviAStaging and monitoring response to treatment in primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of bone marrow using (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographyClin Lymphoma20011430330611707846

- MuSAiLFanFPrognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients: an updated dose– response meta-analysisCancer Cell Int20181811930166942

- AkhtarSEl WeshiARahalMHigh-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant in adolescent patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaBone Marrow Transplant201045347648219734949

- ParkSLeeJKoYHThe impact of Epstein–Barr virus status on clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphomaBlood2007110397297817400912

- BloomfieldCDMckennaRWBrunningRDSignificance of haematological parameters in the non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomasBr J Haematol197632141461259924

- ConlanMGArmitageJOBastMWeisenburgerDDClinical significance of hematologic parameters in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at diagnosisCancer1991675138913951991302

- YiSHXuYZouDHPrognostic impact of bone marrow involvement (BMI) and therapies in diffuse large B cell lymphomaZhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi2009305307312 Chinese19799125

- FerreriAJFreschiMDell’oroSPrognostic significance of the histopathologic recognition of low- and high-grade components in stage I-II B-cell gastric lymphomasAm J Surg Pathol20012519510211145257

- OchiYKazumaYHiramotoNUtility of a simple prognostic stratification based on platelet counts and serum albumin levels in elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphomaAnn Hematol201796118

- ChenLPLinSJYuMSPrognostic value of platelet count in diffuse large B-cell lymphomaClin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk2012121323722138101

- LiebmanHOther immune thrombocytopeniasSemin Hematol2007444 Suppl 5S24S3418096469

- KolbGFMyelopoiesis and bone marrow function in elderly tumor patientsZ Gerontol Geriatr2012453197200 German22451304

- BertiniMBoccominiCCalviRThe influence of advanced age on the treatment and prognosis of diffuse large-cell lymphoma (DLCL)Clin Lymphoma20011427828411707842

- ChangYCuiMFuXLymphoma associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a single-center retrospective studyOncol Lett20181611275128430061947

- LeeDEMartinez-EscalaMESerranoLMHemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJAMA Dermatol2018154782883129874360

- HammerstrømJGranulocyte colony-stimulating factor in neutropenia secondary to lymphoid bone marrow infiltrationTidsskr Nor Laegeforen19961164484486 Norwegian8644050

- MoritaYEmotoMSerizawaKHIV-negative primary bone marrow Hodgkin lymphoma manifesting with a high fever associated with hemophagocytosis as the initial symptom: a case report and review of the previous literatureIntern Med201554111393139626027994

- LiLDuanWZhangLThe efficacy and safety of gemcitabine, cisplatin, prednisone, thalidomide versus CHOP in patients with newly diagnosed peripheral T-cell lymphoma with analysis of biomarkersBr J Haematol2017178577278028597542

- RosadoFGKimASHemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on diagnosis and pathogenesisAm J Clin Pathol2013139671372723690113

- KimMSChoYUJangSA case of primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting with fibrillar projections and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosisAnn Lab Med201737654454628840996

- WilsonWHTeruya-FeldsteinJFestTRelationship of p53, Bcl-2, and tumor proliferation to clinical drug resistance in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomasBlood19978926016099002964

- MoskowitzCHSchöderHTeruya-FeldsteinJRisk-adapted dose-dense immunochemotherapy determined by interim FDG-PET in advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol201028111896190320212248

- LaiGMChenYNMickleyLAFojoATBatesSEP-glycoprotein expression and schedule dependence of adriamycin cytotoxicity in human colon carcinoma cell linesInt J Cancer19914956967031682280

- JermannMJostLMTavernaCRituximab-EPOCH, an effective salvage therapy for relapsed, refractory or transformed B-cell lymphomas: results of a Phase II studyAnn Oncol200415351151614998858

- IntragumtornchaiTBunworasateUNakornTNRojnuckarinPRituximab-CHOP-ESHAP vs CHOP-ESHAP-high-dose therapy vs conventional CHOP chemotherapy in high-intermediate and high-risk aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaLeuk Lymphoma20064771306131416923561

- TillyHLepageECoiffierBIntensive conventional chemotherapy (ACVBP regimen) compared with standard CHOP for poor-prognosis aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2003102134284428912920037

- LiQCYuanXLWangYFClinical outcomes of different regimens for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with bone marrow involvement: analysis of 148 casesZhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi2008884254257 Chinese18361837

- KazamaHTeramuraMYoshinagaKMasudaAMotojiTLong-term remission of primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with high-dose chemotherapy rescued by in vivo rituximab-purged autologous stem cellsCase Rep Med20122012957063 :1–323118770

- PonzoniMCiceriFCrocchioloRFamosoGDoglioniCIsolated bone marrow occurrence of classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma in an HIV-negative patientHaematologica2006913Ecr0416533731

- CacoubLTouatiSYverMIsolated bone marrow Hodgkin lymphoma in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient: a second caseLeuk Lymphoma20145571675167724070425

- DholariaBAlapatDArnaoutakisKPrimary bone marrow Hodgkin lymphoma in an HIV-negative patientInt J Hematol201499450350724532438

- GérardLOksenhendlerEHodgkin’s lymphoma as a cause of fever of unknown origin in HIV infectionAIDS Patient Care STDS2003171049549914588089

- PonzoniMFumagalliLRossiGIsolated bone marrow manifestation of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphomaMod Pathol200215121273127812481007

- SalamaMEPerkinsSLMariappanMRImages in HIV/AIDS. primary bone marrow presentation of Epstein–Barr virus-driven HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphomaAIDS Read2007171260460518178979

- ShahBKSubramaniamSPeaceDGarciaCHIV-associated primary bone marrow Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a distinct entity?J Clin Oncol20102827e459e46020679601

- SuzukiTKusumotoSMasakiACD30-positive primary bone marrow lymphoma mimicking Hodgkin lymphomaInt J Hematol2015101210911125430086

- GudginERashbassJPulfordKJErberWNPrimary and isolated anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the bone marrowLeuk Lymphoma200546346146315621840

- SzomorAAl SaatiTDelsolGPrimary bone marrow T-cell anaplastic large cell lymphoma with triple M gradientPathol Oncol Res200713326026217922057

- KagoyaYSaharaNMatsunagaTA case of primary bone marrow B-cell non Hodgkin’s lymphoma with severe thrombocytopenia: case report and a review of the literatureIndian J Hematol Blood Transfus201026310610821886395

- KosugiSWatanabeMHoshikawaMPrimary bone marrow lymphoma presenting with cold-type autoimmune hemolytic anemiaIndian J Hematol Blood Transfus201430Suppl 127127425332595

- SumiMIchikawaNShimizuIPrimary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the bone marrow complicated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia and erythroid hypoplasiaRinsho Ketsueki2007487571575 Japanese17695307

- NíáinleFHamnvikOPGulmannCDiffuse large B-cell lymphoma with isolated bone marrow involvement presenting with secondary cold agglutinin diseaseInt J Lab Hematol200830544444518205841

- LiuHYiSLiuEPrimary bone marrow diffuse large B cell lymphoma: three case reports and literature reviewZhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi20143510914917 Chinese25339329

- WangWZhouGYZhangWEarly relapse in a case of primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-CHOPImmunotherapy20179537938528357915

- RenSTaoYJiaLUFever and arthralgia as the initial symptoms of primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a case reportOncol Lett20161153428343227123129

- HuYChenSLHuangZXGaoWAnNCase report diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the primary bone marrowGenet Mol Res20151426247625026125825

- NiscolaPPalombiMFratoniSPerrottiAde FabritiisPPrimary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the bone marrow in a frail and elderly patient successfully treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisoneBlood Res201348429629724466557

- SharmaPAhluwaliaJSachdevaMUPrimary bone marrow T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a diagnostic challengeHematology2013182858823562349

- ChangHHungYSLinTLPrimary bone marrow diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a case series and reviewAnn Hematol201190779179621181164

- AlvaresCLMatutesEScullyMAIsolated bone marrow involvement in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a report of three cases with review of morphological, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic findingsLeuk Lymphoma200445476977515160954

- NagasakiAHirooHTairaNTakasuNMasudaMPrimary malignant lymphoma of bone marrowIntern Med200443652452515283193