Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with progress-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS).

Patients and methods

A total of 40 patients were enrolled in this study at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China, from 2006 to 2016. The study retrospectively analyzed clinical and pathological data, and associations of these variables with PFS and OS were evaluated.

Results

The age of the patients at the time of diagnosis ranged from 16 to 73 years. Abnormal vaginal bleeding was the most commonly observed symptom. The tumor size ranged from 2 to 19 cm. The tumor locations were as follows: vulva (1 case), ovary (2 cases), broad ligament (2 cases), cervix (7 cases), and uterus (28 cases). A total of 34 (85%) and 6 (15%) patients underwent complete and ovarian preservation surgery, respectively. Notably, 33 (82.5%), 13 (32.5%), and 5 (12.5%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormone treatment, respectively. Lymph node dissection was performed in 15 (37.5%) patients (positive rate: 7.4%), 16 (40%) patients underwent omentectomy (positive rate: 10%), and 12 (30%) patients underwent peritoneal lavage cytology (positive rate: 0%). Eighteen (45%) patients had lymphovascular space invasion, 13 (32.5%) patients had uterine fibroids, and 11 (27.5%) patients were diagnosed with endometriosis. Moreover, the levels of CA125 in the serum were measured prior to and following treatment. The median PFS and OS were 9 and 24 months, respectively. Eventually, 29 (72.5%) patients experienced relapse and 19 (47.5%) patients expired due to the disease.

Conclusion

Patients with advanced HG-ESS (stage II–IV) were associated with poor prognosis. The minimum value of CA125 and endometriosis were independent risk factors for PFS. The stage of disease, size of the tumor, minimum and average values of CA125, menopause, history of uterine leiomyoma, and endometriosis were independent risk factors for OS. The combination of surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy may improve the PFS of patients in the early stage of the disease.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) is the second most common type of uterine mesenchymal neoplasm following leiomyosarcoma.Citation1–Citation3 It accounts for 7%–25% of all uterine mesenchymal tumors and <1% of all uterine tumors.Citation1,Citation4

In 2013, Lee et al provided the basis for re-introducing the high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) category in the 2014 WHO classification system.Citation1,Citation5 They described seven cases of uterine sarcoma that harbored the t(10;17) (q22;p13) mutation. These tumors were characterized by three aspects, which distinguished them histologically and immunohistochemically from low-grade ESS (LG-ESS). First, they exhibited extensive invasion. Second, they were composed of round cells with brisk mitotic activity that lacked expression of estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR). Lastly, a 14-3-3 oncoprotein was identified through whole transcriptome sequencing, caused by the fusion of YWHAE (14-3-3ε) with NUTM2A/B.Citation6 LG-ESS is an indolent tumor with favorable prognosis, which is often sensitive to hormone therapy. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for stage I patients is >90%, while that of patients in stages III and IV is 50%.Citation4,Citation7–Citation9 However, patients with HG-ESS experience earlier and more frequent recurrences (often <1 year) and are at a higher risk of death due to the disease. The median progress-free survival (PFS) and OS ranges from 7 to 11 months and 11 to 23 months, respectively.Citation10 Due to the rarity and invasiveness of HG-ESS, more than half of the patients are already in the advanced stages of the disease at the time of consultation. Most often, the diagnosis is made postoperatively following histopathological review.Citation11

Complete surgery for ESS is defined as hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) in stage I patients and removal of enlarged nodes and debulking of obvious extra uterine disease in stage II–IV patients.Citation12 The dissection of lymph nodes and the role of adjuvant therapy in the treatment of HG-ESS remain controversial.Citation12–Citation15 At present, the Gynecologic Cancer Inter Group does not recommend lymphadenectomy for patients with HG-ESS.Citation10 Clinical trials have not shown definite survival benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and this research has been hampered by the rarity and heterogeneity of this disease.Citation11

Research studies provided a great understanding of the disease. However, information regarding the selection of treatment and prognostic factors remains scarce due to the limited experience with ESS (ie, availability of few small case series and case reports).Citation16 The number of cases in our study is comparatively large, rendering our results more reliable vs previous reports. In most ESS patients, the levels of CA125 fluctuate within the normal range. Hence, there is currently no study investigating the relationship between the levels of CA125 in the serum and disease progression. However, we found a close correlation between the levels of CA125 in the serum and disease development even if the CA125 level fluctuated within the normal range. The aim of this study was to deepen our understanding of this disease and to identify the factors influencing prognosis.

Patients and methods

This was a single-center study conducted at the Peking Union Hospital Gynecology and Obstetrics, Beijing, China. The Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital has reviewed the study protocol and has determined that 1) the applicant(s) are qualified to conduct the proposed study; 2) the informed consent to participate in this clinical study is waived due to the nature of the study; and 3) personal information was not disclosed. This study strictly abides to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients with a definite pathologic diagnosis of HG-ESS (n=45) treated at the hospital from 2006 to 2016 were enrolled in this study. The histological classification was performed based on the 2014 WHO classification. We excluded patients with other neoplastic diseases (three cases with undifferentiated uterine sarcoma and one case with LG-ESS) and those for whom detailed follow-up data (n=2) were not available.

The clinical data were obtained through clinical record documents and telephone interviews. Data comprise demographic characteristics, history of uterine leiomyoma (ie, previous imaging data suggested uterine leiomyoma), surgical and adjuvant treatment, serum levels of CA125, pathological results, time and site of recurrence, and clinical outcomes. All patients were followed-up for at least 15 months. Outcome indicators included PFS and OS. PFS was defined as the time from disease treatment to relapse or to final follow-up, while OS was defined as the time from the beginning of treatment to death or to the last follow-up. The stage of disease was determined according to the 2009 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging for uterine sarcomas.

Surgical procedures included complete surgery, ovarian-preserving surgery, and resection of local lesions. Adjuvant therapy incorporated radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy. The chemotherapy regimens used were: PEI (cisplatin/epirubicin/ifosfamide), PE (cisplatin/epirubicin), TI (taxol/ifosfamide), and TC (taxol/cisplatin). The radiotherapy treatment comprises external (44–60 Gy/26–30 f) and/or intravaginal radiation (5–30 Gy/1–5 f). The radiation dose and location were determined according to the patient’s condition. Hormone therapy included aromatase inhibitor or GnRH-a.

We classified the patients into four subgroups to analyze the factors affecting survival in early (stage I) and late (stage II–IV) patients, respectively: 1) surgery, 2) surgery + chemotherapy, 3) surgery + chemotherapy + radiation, and 4) surgery + chemotherapy + hormone therapy.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables were represented by the median (minimum–maximum). The categorical data were expressed as percentage (constituent ratio) and the chi-squared test was used for the analysis. If the theoretical frequency was too small, Fisher’s exact test was used. Cox regression analysis was performed using the step-wise method. After adjusting for the influence of other factors, a multivariate Cox regression model was constructed to determine the occurrence of the endpoint event and the time of this occurrence. Statistical significance was assumed at P<0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The baseline information of patients is summarized in . The age of patients at the time of diagnosis ranged from 16 to 73 years (median age: 48.5 years). Abnormal vaginal bleeding was the most commonly observed symptom. Approximately 67% of menopausal women experienced vaginal bleeding and 63% of premenopausal women showed menorrhagia and/or menstrual disorder. Of note, 30% of the patients presented with abdominal discomfort (such as abdominal pain or distension). Moreover, 7% of the patients presented with frequent urination or dysuria.

The sites of the tumors were as follows: vulva (1 case), ovary (2 cases), broad ligament (2 cases), cervix (7 cases), and uterus (28 cases). The tumors in eight patients grew like polyps, and there was a prolapse of the vaginal mass.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of patients

Treatment

A total of 34 (85%) patients underwent initial complete surgery. The other 6 (15%) patients: 1 patient (17 years old, stage IA) underwent cervix conization; 1 patient (16 years old, stage IB) underwent cervix neoplasm resection, 1 patient (17 years old, stage IC) underwent hysterectomy, and 1 patient (35 years old, stage IB) underwent radical vulvectomy. The follow-up time of these patients ranged from 20 to 60 months and without recurrence. Two patients (48 years old, stage IIIB, the disease relapsed 8 months later; 49 years old, stage IVB, expired 12 months after diagnosis) underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy. Five (12.5%) patients underwent reoperation due to recurrence of the disease.

A total of 33 (82.5%) patients received adjuvant treatment: 33 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (14 patients PEI, 11 patients PE, 5 patients TI, and 3 patients TC); 13 (32.5%) patients received radiation therapy; and 5 (12.5%) patients received hormone treatment ().

Table 2 Treatment of patients

Pathological findings

Lymph node dissection was performed in 15 (37.5%) patients, 3 (7.4%) of whom had lymph node metastasis. Sixteen (40%) patients underwent omentectomy, four (10%) of whom had omentum metastases. Tumor cells were not found in 12 (30%) patients who underwent peritoneal lavage cytology. Of the eleven (27.5%) patients with endometriosis, seven (17.5%) postmenopausal patients had adenomyosis. In addition, 18 (45%) patients had lymphovascular space invasion and 13 (32.5%) patients had uterine fibroids.

Outcomes

The median PFS was 9 months (range: 1–92 months) and 29 (72.5%) patients relapsed. Metastasis in the abdominopelvic cavity occurred in 17 (42.5%) patients, while distant metastasis (including lung, liver, vertebra, and brain) occurred in 12 (30%) patients. The median OS was 24 months (range: 1–92 months), and 19 (47.5%) patients expired due to the disease. The 5-year rates for PFS and OS were 17.2% and 5.3%, respectively.

Cox multivariate survival analysis

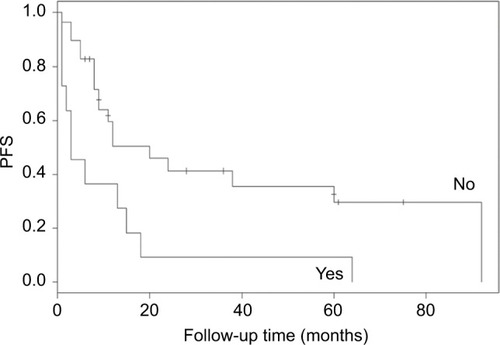

When other factors were corrected, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the minimum value of CA125 (P=0.003) and endometriosis (0.006) were independent risk factors for PFS (P<0.05). The probability of recurrence increased by 1.15-fold (95% CI: 1.042–1.269) for each unit of the minimum value of CA125. Patients with endometriosis were more likely to experience relapse than those without endometriosis (HR: 3.492, 95% CI: 1.536–7.941) ().

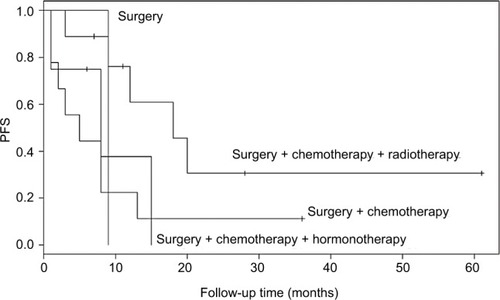

Figure 1 Progress-free survival of patients with or without endometriosis.

Abbreviation: PFS, progress-free survival.

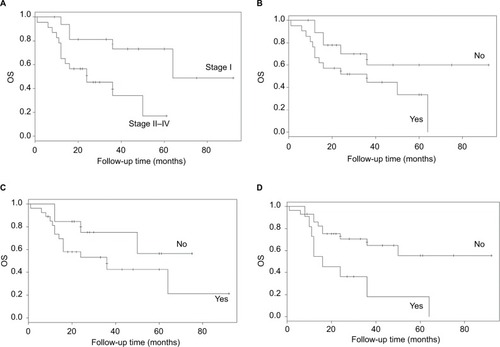

The independent risk factors for OS (P<0.05) were the stage of disease (P=0.001), size of the tumor (P=0.041), minimum and average values of CA125 (P=0.021 and P=0.007, respectively), menopause (P=0.003), history of uterine leiomyoma (P=0.000), and endometriosis (P=0.013) (). The incidence of terminal event was 12.151-fold (95% CI: 2.692–54.852) higher in late-stage vs early-stage patients. The probability of death increased by 2.524-fold (95% CI: 1.037–6.142) for every 1 cm of increase in tumor size. The probability of death increased by 1.234-fold (95% CI: 1.032–1.476) or 1.016-fold (95% CI: 1.004–1.028) for each unit of increase of the minimum or average value of CA125. Patients with history of uterine leiomyoma (HR: 20.782, 95% CI: 3.982–108.473) or with endometriosis (HR: 4.62, 95% CI: 1.385–15.414) and postmenopausal patients (HR: 7.575, 95% CI: 2.001–28.669) were associated with worse outcomes.

Figure 2 OS of patients: (A) stage, (B) menopause, (C) history of uterine leiomyoma, and (D) endometriosis.

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

The prognosis of HG-ESS was not correlated to lymphadenectomy, lymphovascular space invasion, omentectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy.

For patients with early-stage disease, the combination of surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy may improve PFS (). However, the present study did not demonstrate that adjuvant therapy may improve the prognosis of patients with advanced-stage HG-ESS.

Discussion

HG-ESS is a rare pathological type of uterine sarcoma. This disease is often misdiagnosed as uterine leiomyoma or endometrial carcinoma prior to operation owing to a lack of characteristic imaging and clinical manifestations. Information regarding the natural course, prognostic factors, and optimal treatment for HG-ESS is currently limited.Citation10,Citation17 The results of the present study suggested that the minimum value of CA125 and endometriosis were independent risk factors for PFS. The stage of disease, size of the tumor, minimum and average values of CA125, menopause, history of uterine leiomyoma, and endometriosis were independent risk factors for OS. The combination of surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy may improve the PFS of patients with early-stage disease.

HG-ESS typically harbors the YWHAE– FAM22 gene fusionCitation5

However, another group of HG-ESS patients is characterized by the t(X;22) (p11;q13) mutation, resulting in the fusion of the ZC3H7B and BCOR genes.Citation1 BCOR immunohistochemistry is positive in only half of the tumors harboring BCOR rearrangements. However, it is positive in all tumors with the YWHAE rearrangements.Citation18,Citation19 Upregulation of BCOR mRNA expression has been documented in tumors with the YWHAE–NUTM2 fusion.Citation20 Approximately half of the cases with ZC3H7B–BCOR HG-ESS present with FIGO stage III disease.Citation1,Citation21 Recurrences and metastases to the lymph nodes, sacrum/bone, pelvis/peritoneum, lung, bowel, and skin have been reported. Moreover, there is little response to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and aromatase inhibitors.Citation1,Citation22,Citation23

The pathological diagnosis of HG-ESS includes: 1) a tumor with marked mitotic activity (>20–30 mitoses/10 HP fields); 2) loss of hormone receptors; 3) additional sampling to exclude the possibility of HG-ESS with fibrous or myxoid appearance; 4) negative result for smooth muscle markers; 5) diffusely positive for c-kit but negative for DOG1; and 6) diffusely positive for cyclin D1.Citation17 For patients in whom diagnosis and differential diagnosis are difficult, genetic analysis (particularly new-generation sequencing-based RNA-sequencing assay) may assist in identifying the specific genetic type of HG-ESS.Citation1

Patients with HG-ESS often lack expression of ER and PR. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the ovary may be preserved in premenopausal women with HG-ESS. In the present study, six patients underwent ovarian preservation surgery, four of whom were in stage I without recurrence at the end of the follow-up period (60–71 months). Two additional patients with late stage of HG-ESS who were misdiagnosed with uterine leiomyoma underwent hysterectomy and BSO. Both patients expired due to this disease (OS was 10 and 12 months, respectively). Furthermore, the present research found that the prognosis of postmenopausal patients was poor. Therefore, we suggest that surgery with ovarian conservation be considered for young patients with early-stage disease.

The prognostic significance of lymph nodal metastasis and complete lymphadenectomy remains controversial.Citation12,Citation14,Citation24,Citation25 According to the multivariate Cox regression analysis, the present findings demonstrated that lymph node or omentum dissection does not improve prognosis. In a study performed by Seagle et al, it was found that lymph node positivity showed a weak trend toward a strongly negative prognostic association. In addition, women with HG-ESS and no surgical node evaluation had significantly decreased survival.Citation25 The Gynecologic Cancer Inter Group does not recommend lymphadenectomy for HG-ESS.Citation10,Citation26 The risk of lymph node metastases and omental metastases can be negligible.Citation11

In addition to surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy are important adjuvant treatments. Nevertheless, their effectiveness needs to be evaluated. Clinical trials have not shown a definite survival benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy and this research has been hampered by the rarity and heterogeneity of this disease.Citation11 The present results suggested that the combination of surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy may only improve the PFS of patients with early-stage disease. Furthermore, the analysis conducted by Seagle et al provided robust data supporting the modest survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in patients with HG-ESS.Citation26 However, the Gynecological Cancer Group study showed that adjuvant external pelvic radiation did not improve PFS and OS among women with FIGO I–II stage HG-ESS.Citation17,Citation27 We demonstrated that hormone therapy did not improve the prognosis of HG-ESS patients. However, previous studies suggested that after carefully balancing the unproven efficacy vs the possible negative effects, hormonal therapy may be considered for hormone receptor-positive patients with HG-ESS on an individual basis.Citation28

ESS was once referred to as stromal endometriosis and the ectopic endometrium has endometrial interstitial components. Interestingly, we found that the levels of CA125 in the serum and endometriosis were independent risk factors affecting the prognosis of HG-ESS. We also discovered that CA125 may reflect the stage of HG-ESS even if its level fluctuates within the normal range.

A number of studies indicated that the presence of associated endometriosis with ESS suggests the possibility of synchronous ovarian tumors.Citation16,Citation29,Citation30 This is consistent with the present results. Endometriosis is often characterized by increased levels of CA125 and the level of CA125 in the serum is closely related to the severity of the disease. Therefore, we hypothesize that the occurrence and development of ESS is closely related to endometriosis. However, further research is required to confirm this hypothesis.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. This was a single-center, retrospective study involving a limited number of patients. Thus, the conclusions may be affected by the amount of cases. In addition, a proportion of the patients received treatment in other hospitals prior to their admission at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital. This may also limit generalizability and predispose to selection bias. Further multicenter trials involving larger sample sizes are required to confirm the present results.

Conclusion

Treating physicians should be on alert for patients suspected of having uterine myoma or endometrial or cervical polyps. In the absence of a clear diagnosis, curettage or biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis. For patients with advanced HG-ESS, complete resection should be performed as soon as possible after the diagnosis. The combination of surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy may benefit patients with early-stage disease.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HoangLChiangSLeeCHEndometrial stromal sarcomas and related neoplasms: new developments and diagnostic considerationsPathology201850216217729275929

- AbelerVMRøyneOThoresenSDanielsenHENeslandJMKristensenGBUterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patientsHistopathology200954335536419236512

- HarlowBLWeissNSLoftonSThe epidemiology of sarcomas of the uterusJ Natl Cancer Inst19867633994023456457

- PratJMbataniNUterine sarcomasInt J Gynaecol Obstet20151314 SupplS105S11026433666

- LeeCHMariño-EnriquezAOuWThe clinicopathologic features of YWHAE-FAM22 endometrial stromal sarcomas: a histologically high-grade and clinically aggressive tumorAm J Surg Pathol201236564165322456610

- OlivaECarcangiuMLCarineliSGTumours of the uterine corpus-mesenchymal tumoursWorld Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive OrgansLyonIARC Press2014141145

- YenMSChenJRWangPHUterine sarcoma part III-targeted therapy: the Taiwan Association of Gynecology (TAG) systematic reviewTaiwan J Obstet Gynecol201655562563427751406

- ChanJKKawarNMShinJYEndometrial stromal sarcoma: a population-based analysisBr J Cancer20089981210121518813312

- CuppensTTuyaertsSAmantFPotential therapeutic targets in uterine sarcomasSarcoma2015201516114

- PautierPNamEJProvencherDMGynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for high-grade undifferentiated sarcomas of the uterusInt J Gynecol Cancer2014249 Suppl 3S73S7725341584

- BensonCMiahABUterine sarcoma – current perspectivesInt J Womens Health2017959760628919822

- AgarwalRRajanbabuANairIRSatishCJoseGUnikrishnanUGEndometrial stromal sarcoma – a retrospective analysis of factors affecting recurrenceEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2017216929728738297

- GadducciACosioSRomaniniAGenazzaniARThe management of patients with uterine sarcoma: a debated clinical challengeCrit Rev Oncol Hematol200865212914217706430

- LiAJGiuntoliRLDrakeROvarian preservation in stage I low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomasObstet Gynecol200510661304130816319256

- ChuMCMorGLimCZhengWParkashVSchwartzPELow-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: hormonal aspectsGynecol Oncol200390117017612821359

- MasandRPEuscherEDDeaversMTMalpicaAEndometrioid stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 63 casesAm J Surg Pathol201337111635164724121169

- HorngHCWenKCWangPHUterine sarcoma Part II – uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma: the TAG systematic reviewTaiwan J Obstet Gynecol201655447247927590366

- ChiangSLeeCHStewartCJRBCOR is a robust diagnostic immunohistochemical marker of genetically diverse high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, including tumors exhibiting variant morphologyMod Pathol20173091251126128621321

- KaoYCSungYSZhangLBCOR overexpression is a highly sensitive marker in round cell sarcomas with BCOR genetic abnormalitiesAm J Surg Pathol201640121670167827428733

- KaoYCSungYSZhangLRecurrent BCOR internal tandem duplication and YWHAE-NUTM2B fusions in soft tissue undifferentiated round cell sarcoma of infancy: overlapping genetic features with clear cell sarcoma of kidneyAm J Surg Pathol20164081009102026945340

- LewisNSoslowRADelairDFZC3H7B-BCOR high-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas: a report of 17 cases of a newly defined entityMod Pathol201831467468429192652

- PanagopoulosIThorsenJGorunovaLFusion of the ZC3H7B and BCOR genes in endometrial stromal sarcomas carrying an X;22-translocationGenes Chromosomes Cancer201352761061823580382

- HoangLNAnejaAConlonNNovel high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: a morphologic mimicker of myxoid leiomyosarcomaAm J Surg Pathol2017411122427631520

- GadducciACosioSRomaniniAGenazzaniARThe management of patients with uterine sarcoma: a debated clinical challengeCrit Rev Oncol Hematol200865212914217706430

- ChuMCMorGLimCZhengWParkashVSchwartzPELow-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: hormonal aspectsGynecol Oncol200390117017612821359

- SeagleBLShilpiABuchananSGoodmanCShahabiSLow-grade and high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: a National Cancer Database studyGynecol Oncol2017146225426228596015

- ReedNSMangioniCMalmströmHPhase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group Study (protocol 55874)Eur J Cancer200844680881818378136

- DesarIMEOttevangerPBBensonCvan der GraafWTASystemic treatment in adult uterine sarcomasCrit Rev Oncol Hematol2018122102029458779

- YoungRHPratJScullyREEndometrioid stromal sarcomas of the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 23 casesCancer1984535114311556198065

- YoungRHScullyRESarcomas metastatic to the ovary: a report of 21 casesInt J Gynecol Pathol1990932312522373588