Abstract

Purpose

A low body mass index has been associated with high mortalities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and studies reveal that obesity aggravates the clinical effects of COPD. We investigated the impact of obesity on patients newly identified with COPD.

Patients and methods

This population-based, cross-sectional study, used data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) conducted from 2010 to 2012. Through analyses of data from this survey, we compared concurrent comorbid diseases, symptoms, and lung functions between an obese and nonobese group of patients with COPD.

Results

In total, 618 participants were diagnosed with COPD and the average forced expired volume in 1 s (FEV1) was 79.47%±0.69%. Of the total, 30.5% of the subjects were categorized into an obese group. Subjects in the obese group were likely to have metabolic syndrome (P<0.001), hypertension (P=0.02), and a higher number of comorbidities compared to the nonobese group (2.3±0.1 vs 2.0±0.1, P=0.02). In addition, subjects in the obese group showed a lower forced vital capacity (FVC) than subjects in the nonobese group, even after adjusting for covariates (average FVC%, 89.32±1.26 vs 92.52%±0.72%, P=0.037). There were no significant differences in the adjusted FEV1% and adjusted FEV1/FVC between the groups.

Conclusions

Among subjects newly identified with mild COPD, participants in the obese group had more comorbid conditions and showed a lower FVC compared with subjects in the nonobese group, even after adjustment of covariates. These findings show that a combination of obesity and COPD may be a severe phenotype; therefore, early attention should be paid to obesity for the management of COPD patients.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined as a fixed airflow limitation and is associated with a systemic inflammatory response caused by smoking.Citation1 Patients with COPD have numerous comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular disease or lung cancer, which share smoking as a risk factor. Other comorbid conditions, including anxiety, depression, osteoporosis, anemia, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, are commonly concurrent with the presence of COPD.Citation2,Citation3 These comorbid conditions influence the health status and outcome of patients with COPD.Citation4

Obesity, an increasing global health problem,Citation5 is known as an important comorbidity. Numerous pulmonary complications are observed in obese patients.Citation6,Citation7 Although it was performed on different ethnic background, the prevalence of obesity in patients with COPD has been reported to be in a range from 10% to 50%,Citation8,Citation9 and studies have investigated the relationship between obesity and COPD. However, it is somewhat unclear if obesity actually has a detrimental impact on patients with COPD. For example, a low body mass index (BMI) has been regarded as an independent risk factor of mortality in patients with COPD.Citation10 However, several conflicting studies reported more respiratory symptoms, worse restriction of daily activities, worse health-related quality of life, or more health care use in obese patients with COPD.Citation9,Citation11,Citation12 The impact of obesity on COPD is an ongoing controversy to discuss.Citation13 In addition, pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment for COPD may obscure the effect of comorbidities, including obesity. Furthermore, no study has investigated whether obesity affects the health status of patients with mild COPD and no previous history of treatment.

This study analyzed the findings from a general population-based database to identify whether clinical characteristics, including symptoms, quality of life, comorbid diseases, and lung function, were associated with the presence of obesity in patients with COPD and no history of treatment.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) is a population-based health and nutritional survey issued by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention.Citation14 KNHANES V (the 5th version of KNHANES, which was conducted during 2010–2012) was conducted during 2010–2012 and is composed of the following four parts: a health interview survey, a nutrition survey, a health behavior survey, and a health examination survey conducted by trained interviewers. Participants were selected using a stratified, multistage, clustered probability sampling design. Sampling units were based on household registries, including geographic area, age, and sex. The sample represents the total population of Korea.Citation15 This present study applied the KNHANES database, in which all information was anonymized, and was given an exemption from ethical review in Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center because we used public data provided by KNHANES (IRB No 07-2016-26/111).

COPD was defined as a ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <0.7,Citation4 among former or current smokers with at least 10 pack-years. We excluded participants who were already diagnosed with COPD and those who were under treatment for COPD. As spirometry is performed only in subjects aged >40 years, the cohort consisted of patients aged >40 years.

Measurement and classification of variables

Obesity was defined according to the criteria recommended by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, which define a BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2 as obese.Citation16 BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured midway between the costal margin and the iliac crest in a sitting position at the end of a normal expiration. Self-reported questionnaires were used to determine smoking status (former/current) and smoking pack-years.

Blood samples were obtained after overnight fasting, and the levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose were measured. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the criteria established by the International Diabetes Federation,Citation17 and central obesity was defined using a Korean standard.Citation18 Accordingly, subjects with central obesity (waist circumference ≥90 cm for men and ≥85 cm for women) and 2 of 4 factors of metabolic syndrome were included in the study. The factors were serum triglyceride levels ≥150 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women, systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, and fasting plasma glucose ≥100 mg/dL.

Hypertension was defined by a mean systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or current usage of antihypertensive medications.Citation19 Diabetes mellitus was defined by a fasting glucose >126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c >6.5% or current usage of medication for glycemic control.Citation20

Osteoporosis was defined as lumbar spine (L1–4), total femur, or femur neck T-score of <2.5 using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry,Citation21 or current usage of osteoporosis medications. Other comorbidities, including dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, stroke, chronic renal failure, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, lung cancer, pulmonary tuberculosis, and depression, were obtained from self-reported questionnaires. The total number of comorbid conditions was counted and compared between the two groups.

The presence of a wheezing episode was recorded as one of the disease symptoms. The validated Korean version of the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D™) was used for an evaluation of quality of life. The EQ-5D is a generic questionnaire used to assess the health-related quality of life in patients with chronic disease.Citation22 The descriptive system comprises the following five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The average score of the EQ-5D index was calculated by using the South Korean-specific tariff that is based on the time-trade-off method.Citation23

Spirometry was performed for subjects aged >40 years and using standardized equipment by trained technician according to the guidelines from the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society.Citation24 Prebronchodilator spirometry results were measured and analyzed based on a reference value from a predictive equation of the Korean population.Citation25

Statistical analysis

KNHANES data provided population weights. The sample weights of the participants were constructed to represent the Korean population by accounting for the complex survey design, survey nonresponse, and poststratification.Citation14 We applied the complex sample design of the survey using stratification, sampling weight variables, and clustering variables for prevalence production. Categorical variables were reported as weighted percentages, and continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard error (SE). To compare the characteristics of each group, general linear regression (stata command, svyset: regress) was used for continuous variables and a chi-squared test (stata command, svyset: tab) was used for categorical variables.

To compare lung function with the presence of obesity, the adjusted mean values of FEV1%, FVC%, and FEV1/FVC were compared between groups (stata command, svypxcat). Adjustment variables were age, sex, and height, which may independently affect lung function, smoking status, history of tuberculosis, and the presence of metabolic syndrome, and that were significantly different between the two groups. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

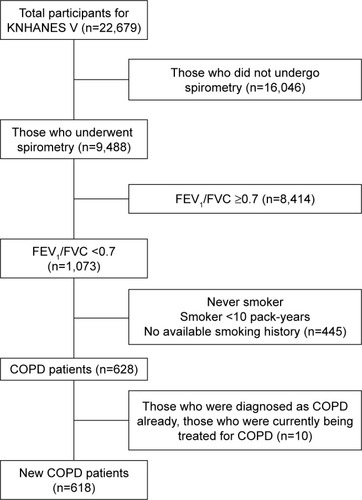

Of the 22,697 participants in the 2010–2012 survey, we included 9,488 participants who had completed a spirometry evaluation. Among the 9,488 subjects who underwent a lung function test, 1,073 had an airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC <0.7). After exclusion of 445 subjects (never a smoker, smoker <10 pack-years, or uncertain smoking history), 628 subjects were defined as having COPD. After exclusion of 10 subjects who were previously diagnosed with or treated for COPD, the data of 618 subjects newly identified with COPD were analyzed for the study (). The included subjects were 63.56±0.54 years old (range 40–91) on average and consisted of 605 (97%) men. The mean BMI value was 23.57±0.14 kg/m2. The average smoking history was 35.10±0.94 pack-years. The mean FEV1 (%, pred) was 79.47%±0.69%, mean FVC (%, pred) was 91.83%±0.64%, and mean FEV1/FVC was 0.63±0.00. The majority of the enrolled subjects with COPD were categorized as “mild” COPD cases in terms of severity assessed by FEV1 (%, pred), which was nearly an average of 80%. Among 618 total subjects, stage 1, 2, and 3 had 308 (51%), 298 (47%), and 13 (2%), respectively. There was no subject belonging to stage 4. In 424 nonobese subjects, 225 (53%), 190 (44%), and 9 (2%) were classified as stage 1, 2, and 3 according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage. In 194 obese subjects, 82 (44%), 108 (54%), and 4 (2%) belonged to stage 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Chi-squared test (stata command, svyset: tab) was used for comparison of categorical variables, but no significant difference was found between nonobese and obese group (P=0.150).

Figure 1 Flowchart for participants through the study.

Obese subjects (BMI >25 kg/m2) comprised 30.5% of the subjects, and multiple variables were compared between the obese and nonobese groups ().

Table 1 Demographic information and comorbidities of obese and nonobese patients with COPD

Subjects in the obese group were younger than the other group (P=0.03), but no difference was observed in sex of the subjects between groups. There were more former smokers in the obese group (P=0.04), but smoking pack-years did not differ between the groups. Subjects in the obese group had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome (41.5% vs 7.1%, P<0.001), including higher triglycerides (P=0.04) and fasting plasma glucose (P=0.02) levels. Hypertension was more common (P=0.02) in the obese group, whereas a history of tuberculosis was less common (P=0.05). The total number of comorbid conditions was higher in the obese group than the nonobese group (2.3±0.1 vs 2.0±0.1; P=0.02).

Wheezing episodes seemed to be more common in the obese group, but there was no statistical significance. The EQ-5D index was comparable between the two groups (). FVC (%, pred, P=0.01) and FEV1/FVC (P=0.04) were significantly lower in the obese group.

Table 2 Symptoms and unadjusted pulmonary function of obese and nonobese patients with COPD

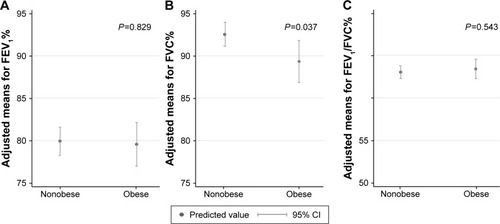

After adjusting for age, sex, height, smoking status, history of tuberculosis, and metabolic syndrome, subjects in the obese group showed a significantly lower FVC compared with subjects of the nonobese group (89.32%±1.26% vs 92.52%±0.72%, P=0.037). There was no significant difference in FEV1 (79.54%±1.32% vs 79.92%±0.85%, P=0.829) and FEV1/FVC (0.63±0.00 vs 0.62±0.00, P=0.543) between the groups ().

Figure 2 Adjusted lung function of obese and nonobese patients with COPD.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI, confidential interval; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

Discussion

This study found that obesity is associated with more comorbid conditions and lower FVC in subjects newly identified with mild COPD.

It is well known that obesity may be accompanied by numerous pathological conditions. Similar to the findings in several previous studies, this study found that obese patients have more comorbid conditions than nonobese patients.Citation26,Citation27 In this study, obese patients with COPD presented with a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome than nonobese patients with COPD. Hypertension and metabolic syndrome are common risk factors of cardiovascular disease.Citation28 Cardiovascular disease is a well-known risk factor of increased hospital admission and mortality rate in patients with COPD,Citation29 which explains 9%–27% of their deaths in large clinical trials.Citation30–Citation32 Therefore, obesity should be considered as a deteriorating prognostic factor when combined to COPD.

Obese patients with COPD presented with lower FVC than non-obese COPD patients during a pulmonary function test. This is similar to the results of numerous studies,Citation33–Citation35 with the exception of a few reports.Citation36 It has been thought that a lower FVC in obese patients is attributed to mechanical restriction of ventilation function.Citation35 Obesity impairs the diaphragm’s ability to descend and decreases the compliance of the thoracic cage, which leads to a decrease in functional residual capacity and total lung capacity, eventually resulting in restrictive extrathoracic ventilation patterns.Citation12 In addition, a lower FVC may indicate hyperinflation of the lung due to airflow obstruction. Increases in hyperinflation by airflow obstruction may result in a reduction in FVC due to an increase in residual volume (total lung capacity = residual volume + vital capacity). An American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society consensus paper stated that a low FVC with or without a low FEV1/FVC may be due to an obstructive ventilatory abnormality.Citation37 In a previous study, vital capacity and inspiratory capacity decreased linearly with the progression of airflow obstruction throughout a continuum of hyperinflation from mild to more severe COPD.Citation38 In this study, patients with COPD seemed to show more wheezing episode (12.6% vs 7.65%), but without statistical significance (P=0.140).

These results suggest that management of obesity may be necessary for patients with even mild COPD. The current guideline, the GOLD, included cessation of smoking as a nonpharmacologic treatment, as well as physical activity, rehabilitation, and vaccination.Citation39 In our study, patients with COPD and without obesity presented with a lower number of comorbidities and better FVC. Therefore, weight reduction may be included as another therapeutic recommendation for patients with mild COPD and with an obese phenotype.Citation39

This study has several strengths. First, it analyzed a treatment-naïve general population. COPD treatments may act as possible confounders. For example, COPD medications improve lung function test results,Citation30,Citation40 and systemic corticosteroid usage for acute exacerbation may increase oral intake or risk of truncal obesity, especially in advanced diseases.Citation41 Second, this was a nationwide, cross-sectional study based on reliable data with an appropriate survey design. Third, we analyzed blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1c levels for evaluation of comorbid conditions, including hypertension and diabetes. This provided more detailed analyses than a mere examination of the presence of those conditions.

This study also has several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, we were unable to verify the causality between obesity and differences in clinical outcomes of COPD. Second, as postbronchodilator spirometry was not available for this survey, we used prebronchodilator spirometry and fixed FEV1/FVC ratio criteria for COPD diagnosis. It might have overestimated the number of COPD subjects and resulted in unwanted inclusion of asthmatic subjects in the study. To avoid this, we supplemented smoking history to define COPD and tried to exclude participants with smoking history <10 pack-years and past treatment history. Third, there were insufficient data for evaluating symptoms or quality of life relevant to COPD. For objective indicators, oxygen saturation value or exercise capacity was not available. For symptoms and quality of life, an appropriate questionnaire or the scoring system (eg, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, modified Medical Research Council, and COPD assessment test) was not available. Fourth, in this study, obesity did not influence the patient’s quality of life. This was in disagreement with a couple of previous studies with similar design that found a decreased quality of life in obese patients with COPD.Citation42,Citation43 This may have been due to the inclusion of only new COPD cases, which may have been characterized by milder disease.

Conclusion

Among patients newly identified with COPD by a nationwide survey, obese participants have more comorbid conditions and showed a lower FVC than nonobese group even after adjustment of covariates. This suggests that the combination of obesity and COPD could present a severe phenotype, therefore attention needs to be paid to the management of obesity, even in mild COPD patients.

Author contributions

JHP designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. HSC planned the study and provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript. JKL, EYH, and DKK designed the study, analyzed data, and provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FabbriLLuppiFBegheBRabeKComplex chronic comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J200831120418166598

- Van ManenJBindelsPIJzermansCVan der ZeeJBottemaBSchadeEPrevalence of comorbidity in patients with a chronic airway obstruction and controls over the age of 40J Clin Epidemiol200154328729311223326

- CavaillèsABrinchault-RabinGDixmierAComorbidities of COPDEur Respir Rev20132213045447524293462

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD Available from: http://www.goldcopd.comAccessed October 20, 2016

- World Health OrganizationObesity: Preventing and Managing the Global EpidemicWorld Health Organization2000 Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42330Accessed October 20, 2016

- BhasinDSharmaASharmaSKPulmonary complications of obesityObesity (Silver Spring)2015131144

- JubberARespiratory complications of obesityInt J Clin Pract200458657358015311557

- SteutenLMCreutzbergECVrijhoefHJWoutersEFCOPD as a multi-component disease: inventory of dyspnoea, underweight, obesity and fat free mass depletion in primary carePrim Care Respir J2006152849116701766

- EisnerMDBlancPDSidneySBody composition and functional limitation in COPDRespir Res200781117207287

- LandboCPrescottELangePVestboJAlmdalTPPrognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916061856186110588597

- DivoMJCabreraCCasanovaCComorbidity distribution, clinical expression and survival in COPD patients with different body mass indexChronic Obstr Pulm Dis201412229238

- O’DonnellDECiavagliaCENederJAWhen obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease collide. Physiological and clinical consequencesAnn Am Thorac Soc201411463564424625243

- FranssenFO’DonnellDGoossensGBlaakEScholsAObesity and the lung: 5 Obesity and COPDThorax200863121110111719020276

- KweonSKimYJangM-JData resource profile: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES)Int J Epidemiol2014431697724585853

- Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC)The Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES V) 2010–2012Seoul, South KoreaMinistry of Health and Welfare & Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2010

- Korean Endocrine Society and Korean Society for the Study of ObesityManagement of obesity, 2010 recommendationEndocrinol Metab2010254301304

- AlbertiGZimmetPShawJMetabolic syndrome – a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes FederationDiabet Med200623546948016681555

- ParkHSLeeSYKimSMHanJHKimDJPrevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Korean adults according to the criteria of the International Diabetes FederationDiabetes Care200629493393416567843

- ManciaGFagardRNarkiewiczK2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Blood Press201322419327823777479

- American Diabetes AssociationStandards of medical care in diabetes–2013Diabetes Care201336Suppl 1S11S6623264422

- World Health OrganizationAssessment of Fracture Risk and its Application to Screening for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: Report of a WHO Study GroupRome, ItalyWorld Health Organization1992 Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39142Accessed October 20, 2016

- GroupTEEuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy199016319920810109801

- LeeYKNamHSChuangLHSouth Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health statesValue Health20091281187119319659703

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- ChoiJKPaekDLeeJONormal predictive values of spirometry in Korean populationTuberc Respir Dis (Seoul)2005583230242

- JoYSChoiSMLeeJThe relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities: a cross-sectional study using data from KNHANES 2010–2012Respir Med201510919610425434653

- VarelaMVLde OcaMMHalbertRComorbidities and health status in individuals with and without COPD in five Latin American cities: the PLATINO studyArch Bronconeumol2013491146847423856439

- MottilloSFilionKBGenestJThe metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Am Coll Cardiol201056141113113220863953

- BriggsASpencerMWangHManninoDSinDDDevelopment and validation of a prognostic index for health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med20081681717918195198

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- McGarveyLPMagderSBurkhartDCause-specific mortality adjudication in the UPLIFT® COPD trial: findings and recommendationsRespir Med2012106451552122100536

- WiseRAAnzuetoACottonDTiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPDN Engl J Med2013369161491150123992515

- Ochs-BalcomHMGrantBJMutiPPulmonary function and abdominal adiposity in the general populationJ S C Med Assoc20061294853862

- SahebjamiHGartsidePSPulmonary function in obese subjects with a normal FEV1/FVC ratioJ S C Med Assoc1996110614251429

- van den BemtLvan WayenburgCSmeeleISchermerTObesity in patients with COPD, an undervalued problem?Thorax200964764019561286

- Al GhobainMThe effect of obesity on spirometry tests among healthy non-smoking adultsBMC Pulm Med2012121122230685

- PellegrinoRViegiGBrusascoVInterpretative strategies for lung function testsEur Respir J200526594896816264058

- DeesomchokAWebbKAForkertLLung hyperinflation and its reversibility in patients with airway obstruction of varying severityCOPD20107642843721166631

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359151543155418836213

- DallmanMFla FleurSEPecoraroNCGomezFHoushyarHAkanaSFMinireview: glucocorticoids – food intake, abdominal obesity, and wealthy nations in 2004Endocrinology200414562633263815044359

- LambertAAPutchaNDrummondMBObesity is associated with increased morbidity in moderate to severe COPDChest20171511687727568229

- CecereLMLittmanAJSlatoreCGObesity and COPD: associated symptoms, health-related quality of life, and medication useCOPD20118427528421809909