Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is frequently under-recognized and underdiagnosed. To determine the natural history of recognized and unrecognized COPD, we studied the rate of diagnosis, health care utilization, and mortality in patients with airflow limitation (AFL). Three hundred forty-seven outpatients at the Cincinnati Veterans Administration Medical Center performed spirometry and completed a respiratory questionnaire. Patients were followed for a minimum of 30 months and medical records were reviewed for COPD diagnosis, mortality, respiratory-related health care utilization, comorbidities, and respiratory medications. Three hundred twenty-five of 347 (94%) patients performed technically adequate spirometry and completed questionnaires. When AFL was defined by fixed ratio (FR, forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] < 0.7), patients with AFL and a diagnosis of COPD had a higher annual mortality rate (7.1% ± 2% versus 2.4% ± 0.8%, P = 0.01), more hospitalizations per year (0.2 ± 0.06 versus 0.04 ± 0.01, P < 0.001 mean ± standard error of the mean), increased respiratory symptoms (12.0 ± 0.9 versus 7.2 ± 0.6, P < 0.0001), and higher Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage compared with undiagnosed patients. Ninety-two of 137 patients with AFL (67%) had unrecognized AFL; 16 (17%) of the 92 were subsequently diagnosed. When AFL was defined by the lower limit of normal (LLN, FEV1/FVC < LLN), 67 of 103 patients (65%) had unrecognized AFL; 12 (18%) of the 67 were subsequently diagnosed. Patients with AFL defined by FR who were subsequently diagnosed had more emergency department visits per year (0.33 ± 0.11 versus 0.11 ± 0.05, P = 0.009), increased respiratory symptoms (10.2 ± 1.6 versus 6.5 ± 0.7, P < 0.05), and higher GOLD stage, but similar mortality and hospitalizations compared with the persistently undiagnosed patients. The annual rate of documented COPD diagnosis was 7% for both FR and LLN definitions. Patients with AFL and a diagnosis of COPD have more severe disease, higher health care utilization, and mortality than undiagnosed patients. The annual rate of COPD diagnosis is 7% among individuals with unrecognized AFL. Worse AFL, increased respiratory symptoms, and ED visits are associated with a subsequent COPD diagnosis in individuals with unrecognized AFL.

Introduction

Deaths due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been increasing and COPD became the third leading cause of death in the United States in 2009.Citation1–Citation8 COPD occurs commonly in the general US population and among veterans cared for by the Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA). The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) estimated COPD prevalence to be 6.8%–8.5% within the general US population.Citation3 Among veterans hospitalized in the VHA in 2005, COPD was the fourth most common discharge diagnosis; approximately one third of patients and one sixth of all inpatients had a diagnosis of COPD.Citation9 In a utilization review study from 1996 to 2001, 19% of men and 17% of women in the VHA were diagnosed with COPD.Citation9 We performed spirometry in a randomly selected group of veterans at the Cincinnati Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC) and showed that the prevalence of airflow limitation (AFL) was 33%–43% and that COPD was dramatically underdiagnosed by both health care providers and patients.Citation10

Between 52%–91% of individuals with AFL are not diagnosed with COPD because individuals with minimal or no respiratory symptoms are frequently not assessed by pulmonary function testing.Citation11–Citation15 Recent epidemiologic studies have shown poorer outcomes based on declines in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), inflammatory markers, lower respiratory tract infections, and increases in the Body-mass, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise (BODE) index in patients with known AFL.Citation15–Citation20 However, few investigations have measured the outcomes among individuals with unrecognized AFL and the clinical factors that stimulate clinicians to make a diagnosis of COPD. Therefore, we studied the rate of COPD diagnosis, health care utilization, and mortality in patients with unrecognized AFL.

Materials and methods

Subjects were recruited from the outpatient waiting area of the Cincinnati VAMC. The waiting area provided a sample of patients awaiting primary care, mental health, and pharmacy, as well as medical and surgical subspecialty appointments. Patients were recruited in random, chronological order and spirometry was performed according to the 1994 American Thoracic Society guidelines.Citation21 Each participant completed a questionnaire about smoking habits, occupational exposures, respiratory diagnoses, and symptoms.Citation10 AFL was defined by either fixed ratio (FR), the ratio of FEV1 to the forced vital capacity (FVC), <0.70 or lower limit of normal (LLN), FEV1/FVC < LLN as determined by NHANES III.Citation22 Severity of COPD was determined by the modified Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) definitions: GOLD stage 1: pre-bronchodilator FEV1% > 80% of predicted; GOLD stage 2: pre-bronchodilator FEV1% 50%–80% of predicted; GOLD stage 3: pre-bronchodilator FEV1% 30%–50% of predicted; GOLD stage 4: pre-bronchodilator FEV1% < 30% of predicted.Citation23

The Cincinnati VAMC utilizes a comprehensive electronic medical record (EMR) that includes a complete problem list. Patients with a diagnosis of COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis in their problem list and spirometric evidence of AFL by either FR or LLN at the time of recruitment were labeled “previously diagnosed.” Patients with AFL who had a diagnosis of COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis entered into their problem list after the original study were termed “subsequently diagnosed,” and those with AFL who were never diagnosed with COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis were labeled “persistently undiagnosed.” Patients with FVC < 80% of predicted without AFL were classified as “restricted.” Those individuals without AFL and an FVC ≥ 80% of predicted were categorized as “normal.”

We reviewed patients’ medical records and recorded information regarding current COPD diagnosis, active respiratory medications, BMI, cardiac comorbidities, vital status, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital admissions caused by respiratory symptoms. Cardiac related comorbid diagnoses included atrial fibrillation, systolic or diastolic congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease.

The date of each patient’s recruitment was recorded as well as date of death where applicable. The duration of follow-up for patients who survived to the end of the study ranged from 32 to 53 months. Each patient’s outcomes were normalized to determine the annual rate for each measured parameter.

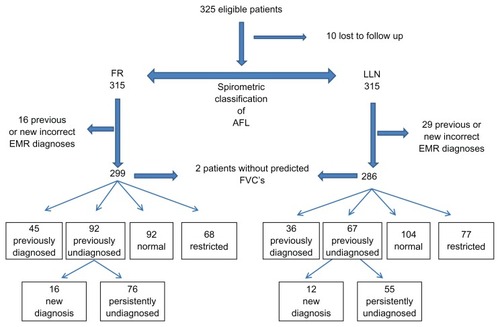

Patients with no EMR notes for more than 1 year after recruitment and were not recorded as deceased were considered lost to follow-up and excluded. Patients with a diagnosis of COPD in the EMR but no AFL on spirometry were also excluded ().

Figure 1 Flow diagram of cohort analyzed using FR (FEV1/FVC < 0.7) and LLN (FEV1/FVC < LLN).

Abbreviations: AFL, airflow limitation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EMR, electronic medical record; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FR, fixed ratio; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal.

All quantitative variables are described using appropriate summary statistics (mean, median, and standard deviation); categorical variables are presented using frequency and proportions. Graphs were produced using Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s and Student’s t-tests.Citation24 Significance was set at P < 0.05.

The study protocol was approved by the Cincinnati VAMC Research and Development Committee and the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board. Informed consent and Health Information Portability and Accountability Authorization were obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Results

Ninety-four percent of patients performed adequate spirometry and completed questionnaires. The charts of these patients were reviewed and only ten patients (3%) were lost to follow-up. One patient who had AFL by both FR and LLN had an accurate diagnosis of COPD deleted from the medical record and was removed from the analysis. In addition, 16 patients were misdiagnosed with COPD using FR and 29 patients were misdiagnosed by LLN. These patients with a chart diagnosis of COPD that was not supported by AFL on spirometry were excluded. Additionally, two patients without AFL were eliminated from analysis because they did not have predicted FVC values ().

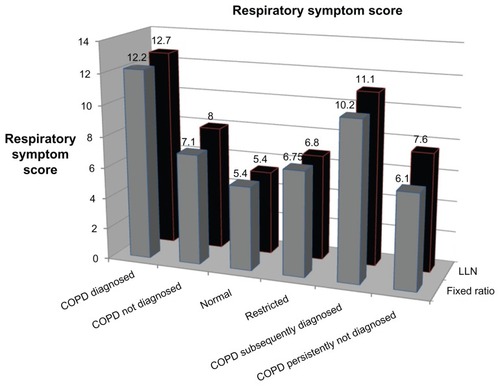

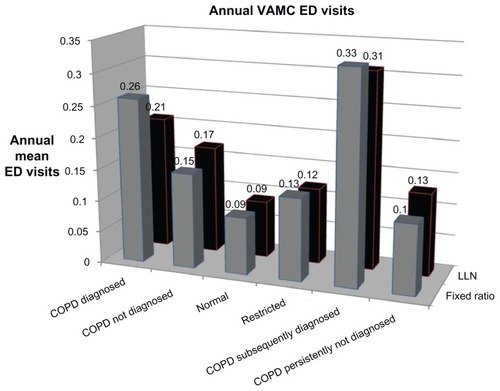

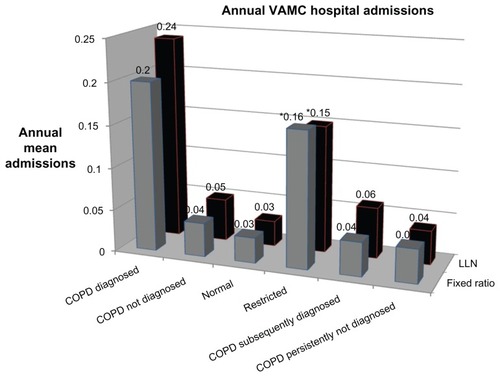

The percentage of patients defined as normal, restricted, previously diagnosed, subsequently diagnosed, and persistently undiagnosed were similar regardless of whether the FR or LLN definition of AFL was used. The demographics, respiratory symptoms, health care utilization, and mortality for these groups are presented in and –.

Table 1 Comparisons of all subsets of diseased patients by age, BMI, baseline pulmonary data, and prescription medications, as well as clinical outcome data using health care utilization and mortality

Figure 2 Mean symptom scores of study subjects showing spirometric classification, and diagnostic status.

When AFL was defined by FR, patients with AFL and a diagnosis of COPD had a higher annual mortality rate, more annual hospitalizations, increased respiratory symptoms, and higher GOLD stage compared with those who did not have a COPD diagnosis (). Respiratory medications were more frequently prescribed for individuals with AFL and a diagnosis of COPD than for those who were not diagnosed with COPD (). Similar findings were present when AFL was defined by LLN.

A similar percentage of patients with AFL as defined by FR or LLN were previously undiagnosed with COPD; and a similarly low percentage of patients with AFL as defined by FR or LLN (17% and 18%, respectively) were subsequently diagnosed with COPD. The annual COPD diagnostic rate was 7% regardless of which AFL definition was used. Those individuals with AFL who were subsequently diagnosed with COPD had more respiratory symptoms, greater proportion of GOLD stage 3 and 4, higher respiratory medication use, and more ED visits than those who were persistently undiagnosed ().

compares the persistently undiagnosed group to the normal patients included in this study. The persistently undiagnosed group was older and had more respiratory symptoms and lower FEV1 than the normal population. However, despite these initial differences, there were no differences in subsequent health care utilization or mortality.

Table 2 Comparisons of diseased patients without a documented diagnosis of COPD and patients with normal spirometry

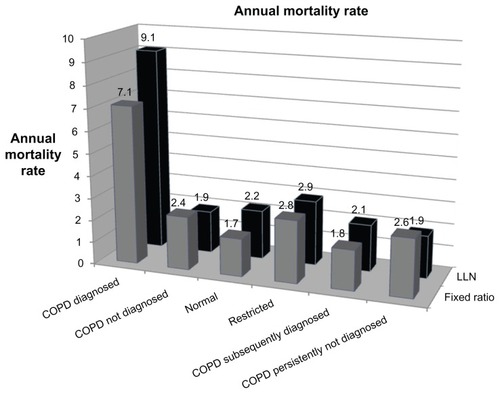

Although hospital admissions occurred most frequently in patients with a diagnosis of COPD, ED visits were greatest among those individuals who were subsequently diagnosed with COPD ( and ). The annual mortality rate was greatest for those patients with a previous diagnosis of COPD: 7.1% for FR and 9.1% for LLN ().

Figure 3 Mean number of annual emergency department visits per patient.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; LLN, lower limit of normal; VAMC, Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Figure 4 Mean number of annual hospitalizations per patient.

Notes: *One patient had four admissions during the 6 months after the recruitment period prior to his death, contributing half of all admissions for the entire group. Data presented for completeness; without this outlier the restricted population values are similar to that of the normal population.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LLN, lower limit of normal; VAMC, Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Figure 5 Annual mortality rate during study period.

Fifty-four percent of the participants did not have AFL by FR and 63% did not have AFL by LLN. Of the patients without AFL, 43% had an FVC < 80% of predicted, regardless of the AFL definition, and were categorized as restricted. Patients with restriction were older and had a greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease than patients with normal spirometry ().

Table 3 Comparisons of patients with decreased FVC (restricted) and normal spirometry

Discussion

Most studies have measured the diagnosis of COPD among patients at risk or with known comorbidities, but our study provides a unique opportunity to determine the rate of COPD diagnosis in a group of undiagnosed patients with AFL.Citation25–Citation27 Approximately 7% of patients with AFL were diagnosed with COPD annually and these patients had greater respiratory symptoms, used more respiratory medications, and visited the ED more often than those individuals with AFL who were not diagnosed with COPD. Review of the Lung Health Study suggests that smokers with lower lung function have accelerated rates of FEV1 decline and increased mortality.Citation28

Although still controversial, recent investigations increasingly suggest benefits for the early detection and treatment of COPD.Citation29–Citation31 Smoking cessation is the primary intervention for the prevention and treatment of COPD and may be more beneficial for smokers with fewer respiratory symptoms and minimal AFL than those with diagnosed COPD.Citation32,Citation33 The effect of undiagnosed COPD on quality of life and patient health is poorly studied, but undetected AFL may impair daily activities with subsequent loss of physical conditioning and erosion of social interactions.Citation34

In a study of the medical costs of undiagnosed COPD, MapelCitation35 and coworkers showed that the average total costs were higher by US$1282 in the 24 months prior to COPD diagnosis and US$2489 greater in the year before diagnosis. The average incremental medical and pharmaceutical cost for undiagnosed COPD is estimated to be $2527 and increases with time, rising precipitously in the month before diagnosis.Citation36 In Sweden, the average annual direct and indirect costs of COPD were $1128 for individuals with a physician diagnosis of COPD compared with $2207 for those who did not have a physician diagnosis.Citation37 Thus, despite estimates that half to two thirds of individuals with COPD are not diagnosed and increasing evidence that early diagnosis of COPD is beneficial and profoundly affects health care utilization and cost, our study suggests that less than 10% of individuals with occult AFL will be diagnosed with COPD each year without a proactive screening or detection program.

The diagnostic process that stimulates a clinician to make a diagnosis of COPD is not well studied. Patients who were initially diagnosed with COPD were older, had more symptoms, and greater physiologic impairment than undiagnosed individuals (). The subsequently diagnosed group had higher symptom scores and used the ED more frequently than the persistently undiagnosed group (). Although the mean FEV1 of the group that was subsequently diagnosed was not different from that of the group that was persistently undiagnosed, 38% of the subsequently diagnosed group were classified as GOLD stage 3 or 4, whereas only 9% of the persistently undiagnosed group were classified as GOLD stage 3 or 4 (). Respiratory symptoms, including breathlessness, cough, and sputum production are critical elements of most COPD screening questionnaires.Citation37–Citation39

The role of health care utilization, especially ED visits and hospitalizations, in the diagnosis of COPD has not been defined. Patients who were subsequently diagnosed with COPD had more ED visits than those who were previously diagnosed and more than twice as many ED visits as the persistently undiagnosed patients (), suggesting a possible role of ED visits in the diagnostic process. Since we could not determine who entered the diagnosis of COPD into the medical record, it was not possible to determine whether there was an increased rate of COPD diagnosis by ED providers or if primary care providers entered a COPD diagnosis after the ED visit. Thus, it is not known which elements of the patient’s clinical history prompt clinicians to establish a COPD diagnosis. ED visits for respiratory complaints may be one stimulus that provokes providers to diagnose COPD.

Recent large, longitudinal studies demonstrated poor quality of life, accelerated FEV1 decline, and increased exacerbation rates and mortality in individuals with mild COPD.Citation14,Citation16,Citation41–Citation44 Consistent with these studies, the persistently undiagnosed patients had significantly more symptoms than individuals with normal spirometry, but less than those who were subsequently diagnosed (–). Although the persistently undiagnosed group received fewer respiratory medications, this study was not structured to determine whether the increased symptoms and health care utilization were due to lack of COPD treatment in the undiagnosed group or whether the lack of treatment was due to underdiagnosis.

The spirometric definition of AFL remains a controversial issue.Citation19,Citation41,Citation45 To mitigate this issue we employed both the FR and LLN definitions of AFL. The prevalence of AFL at the Cincinnati VAMC is much higher than the general population and approximately two thirds of affected patients are not diagnosed with COPD. The prevalence of AFL at the Cincinnati VAMC is much higher than the general population and approximately two thirds of those affected patients are not diagnosed with COPD.Citation10 All of our patients with AFL by LLN also met FR criteria and nine (20%) patients had COPD by FR alone. Those nine patients had predominantly GOLD stage 2 disease and did not contribute significantly to the differences between the groups. Similarly, larger studies have looked at differences between these two definitions and shown differences in quality of life but not in exacerbations or outcomes.Citation41

Recent studies by Mannino and the MESA study group have begun to define a “restricted” lung pathology based on FVC < 80% of predicted and no spirometric evidence of AFL.Citation19,Citation41 These studies found increased mortality in those individuals with restriction compared to those with normal lung function. Our study did not demonstrate survival differences but there were also no differences in respiratory symptoms, BMI, or health care utilization. This study was not originally designed to study this population and a longer follow up period with more participants may be necessary to detect any significant differences. Restrictive lung function occurs in up to 37% of individuals misdiagnosed with COPD and the risk of misclassification was 2.66 fold greater among those who were overweight or obese.Citation46

This study has several limitations. Participants were recruited from a single center and were predominantly older, male smokers. Another limitation is that we only measured ED visits or hospitalizations that were recorded in the VHA EMR; less severe exacerbations that were treated as outpatients or occurred in non-VHA facilities were missed. Consequently, this study likely underestimates health care utilization.

Conclusion

Unprompted clinicians diagnose COPD in only 7% of patients with unrecognized AFL annually. Increased respiratory symptoms and greater frequency of ED visits are associated with the subsequent diagnosis of COPD among patients with unrecognized AFL. Further studies of the factors that stimulate clinicians to recognize and diagnose COPD are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the veterans who participated in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PauwelsRABuistASCalverleyPMJenkinsCRHurdSSGOLD Scientific CommitteeGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116351256127611316667

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood InstituteMorbidity and Mortality: 2012 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung and Blood diseasesUS Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, NIHBethesda MD http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2012_ChartBook.pdfAccessed March 13, 2013

- ManninoDMGagnonRCPettyTLLydickEObstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1984–1994Arch Intern Med2000160111683168910847262

- HoyertDLKochanekKDMurphySLDeath; Final Data for 1997National vital statistics reports4719Hyattsville, MDNational Center for Health Statistics1999 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr47/nvs47_19.pdfAccessed February 14, 2013

- MurrayCJLopezADAlternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease StudyLancet19973499064149815049167458

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- KochanekKDXuJMurphyLSMininoAMKungHCDeaths: Preliminary Data for 2009National vital statistics reports594Hyattsville, MDNational Center for Health Statistics2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_04.pdfAccessed February 14, 2013

- LundbäckBNyströmLRosenhallLStjernbergNObstructive lung disease in northern Sweden: respiratory symptoms assessed in postal surveyEur Respir J1991432572661864340

- McDonaldMHertzRPUtilization of Veterans Affairs Medical Care Services by United States VeteransNew YorkPfizer US Pharmaceuticals2003 Available from: http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Utilization%20of%20Veterans%20Affairs%20Medical%20Care%20Services%20by%20US%20Veterans.pdfAccessed Nov 2010

- MurphyDEChaudhryZAlmoosaKFPanosRJHigh prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban midwestMil Med2011176555256021634301

- RennardSDecramerMCalverleyPMImpact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International SurveyEur Respir J200220479980512412667

- TakahashiTIchinoseMInoueHShiratoKHattoriTTakishimaTUnderdiagnosis and undertreatment of COPD in primary care settingsRespirology20038450450814629656

- DamarlaMCelliBRMullerovaHXPinto-PlataVMDiscrepancy in the use of confirmatory tests in patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failureRespir Care200651101120112417005056

- FukuchiYNishimuraMIchinoseMCOPD in Japan: The Nippon COPD Epidemiology studyRespirology20049445846515612956

- Ackermann-LiebrichUKuna-DibbertBProbst-HenschNMSAPALDIA TeamFollow-up of the Swiss Cohort Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA 2) 1991–2003: methods and characterization of participantsSoz Praventivmed200550424526316167509

- de MarcoRAccordiniSAntòJMLong-term outcomes in mild/moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the European community respiratory health surveyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20091801095696319696441

- BurgelPRNesme-MeyerPChanezPInitiatives Bronchopneumopathie Chronique Obstructive Scientific CommitteeCough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjectsChest2009135497598219017866

- BhowmikASeemungalTASapsfordRJWedzichaJARelation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbationsThorax200055211412010639527

- ManninoDMDiaz-GuzmanEInterpreting lung function data using 80% predicted and fixed thresholds identifies patients at increased risk of mortalityChest20121411738021659434

- Ekberg-AronssonMPehrssonKNilssonJANilssonPMLöfdahlCGMortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitisRespir Res200569816120227

- American Thoracic Society Standardization of spirometryAJRRCM199515211071136

- HankinsonJLOdencrantzJRFedanKBSpirometric Reference Values from a Sample of the General U.S. PopulationAm J of Respir and Crit Care Med19991591791879872837

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [homepage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.orgAccessed February 14, 2013

- GraphPad SoftwareQuick Calcs [webpage on the Internet]La Jolla, CAGraphPad Software, Inc. Available from: http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/Accessed August 1, 2012

- BuistASVollmerWMSullivanSDThe Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Initiative (BOLD): rationale and designCOPD20052227728317136954

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRHallalPCPLATINO TeamWorldwide burden of COPD in high- and low-income countries. Part II. Burden of chronic obstructive lung disease in Latin America: the PLATINO studyInt J Tuberc Lung Dis200812770971218544192

- SchirnhoferLLamprechtBFirleiNUsing targeted spirometry to reduce non-diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201181647648220720402

- DrummondMBHanselNNConnettJEScanlonPDTashkinDPWiseRASpirometric predictors of lung function decline and mortality in early chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185121301130622561963

- DecramerMCelliBKestenSLystigTMehraSTashkinDPUPLIFT investigatorsEffect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trialLancet200937496961171117819716598

- JenkinsCRJonesPWCalverleyPMEfficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH studyRespir Res2009105919566934

- FreemanDLeeAPriceDEfficacy and safety of tiotropium in COPD patients in primary care – the SPiRiva Usual CarE (SPRUCE) studyRespir Res200784517605774

- AnthonisenNRSmoking, lung function, and mortalityThorax200055972973010950888

- PelkonenMTukiainenHTervahautaMPulmonary function, smoking cessation and 30 year mortality in middle aged Finnish menThorax200055974675010950892

- PriceaDFreemanaDClelandJKaplanACerasoliFEarlier diagnosis and earlier treatment of COPD in primary carePrim Care Respir J2011201152220871945

- MapelDWRobinsonSBDastaniHBShahHPhillipsALLydickEThe direct medical costs of undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseValue Health200811462863618194402

- AkazawaMHalpernRRiedelAAStanfordRHDalalABlanchetteCMEconomic burden prior to COPD diagnosis: a matched case-control study in the United StatesRespir Med2008102121744175218760581

- JanssonSALindbergAEricssonACost differences for COPD with and without physician-diagnosisCOPD20052442743417147008

- MartinezFJRaczekAESeiferFDCOPD-PS Clinician Working GroupDevelopment and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS)COPD200852859518415807

- CalverleyPMNordykeRJHalbertRJIsonakaSNonikovDDevelopment of a population-based screening questionnaire for COPDCOPD20052222523217136949

- BaileyWCSciurbaFCHananiaNADevelopment and validation of the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Questionnaire (COPD-AQ)Prim Care Respir J200918319820719492178

- García-RioFSorianoJBMiravitllesMOverdiagnosing subjects with COPD using the 0.7 fixed ratio: correlation with a poor health-related quality of lifeChest201113951072108021183609

- LedererDJEnrightPLKawutSMCigarette smoking associated with subclinical parenchymal lung disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Athersclerosis (MESA)-Lung StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180540741419542480

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKGoldringJJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJATemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179536937419074596

- CasanovaCde TorresJPAguirre-JaímeAThe progression of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is Heterogeneous: The experience of the BODE cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118491015102121836135

- Brito-MutunayagamRAppletonSLWilsonDHRuffinREAdamsRJNorth West Adelaide Cohort Health Study TeamGlobal initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Stage 0 is associated with excess FEV(1) decline in a representative population sampleChest2010138360561320418365

- WaltersJAWaltersEHNelsonMFactors associated with misdiagnosis of COPD in primary carePrim Care Respir J201120439640221687918