Abstract

COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Patients suffer from refractory breathlessness, unrecognized anxiety and depression, and decreased quality of life. Palliative care improves symptom management, patient reported health-related quality of life, cost savings, and mortality though the majority of patients with COPD die without access to palliative care. There are many barriers to providing palliative care to patients with COPD including the difficulty in prognosticating a patient’s course causing referrals to occur late in a patient’s disease. Additionally, physicians avoid conversations about advance care planning due to unique communication barriers present with patients with COPD. Lastly, many health systems are not set up to provide trained palliative care physicians to patients with chronic disease including COPD. This review analyzes the above challenges, the available data regarding palliative care applied to the COPD population, and proposes an alternative approach to address the unmet needs of patients with COPD with proactive primary palliative care.

Background

COPD is a complex, chronic disease defined by lung function limitation on spirometric testing that despite several recent breakthroughs in treatments remains an incurable and life-altering disease.Citation1,Citation2 Worldwide, 210 million people suffer from COPD,Citation3 and in 2002, death from COPD was estimated to be the fifth leading cause of death comprising approximately 7.5% of overall deaths.Citation4 Unlike ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease that are decreasing in prevalence, death from COPD is increasing.Citation4,Citation5 In the United States, for instance, age-standard death rates from COPD increased from 21.4 to 43.4 per 100,000, a change of over 100%, from 1970 to 2002. Conversely, age-standard death rates from stroke and heart disease decreased by 63.1% and 52.1% respectively over this same time frame.Citation5

Despite this large burden of disease, patients with COPD frequently have unmet needs at the end of life.Citation6–Citation9 Although palliative care has been shown to improve symptom burden, quality of life, and patient satisfaction for patients across many diseases,Citation10–Citation15 the majority of patients with COPD die without access to palliative care.Citation7 This review focuses on evaluating the current burden of disease, reviews what is known about palliative care and COPD, and argues that incorporation of palliative care into COPD management could improve overall quality of care delivered to people living with COPD.

Palliative care: what is it and what can it do?

Palliative care began in the 1960s with the beginning of the hospice movement and was focused on symptom management at the end of life.Citation16 Today, however, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as:

An approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.Citation17

Using this new framework, palliative care now extends throughout the course of a patient’s illness from disease onset through the terminal phase of illness.

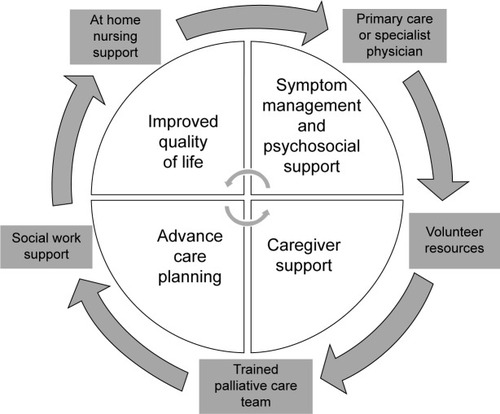

Proactive approaches to palliative care involve a variety of care models. While some models include direct interactions with a trained palliative care physician, other models employ a multidisciplinary team of social workers, physicians, and nurses to provide intensive outpatient resources. All care models focus on improving the symptoms and psychosocial needs of the patient and also actively engage the family and caregivers in training and support as shown in .

Outpatient palliative care improves patient quality of life, decreases symptom burden, and in some cases even improves mortality.Citation12,Citation15,Citation18,Citation19 There are also potential significant financial benefits to the proactive use of palliative care. Kaiser Permanente, a US-based vertically organized health maintenance organization, found that the care for patients living with serious illness who received a multidisciplinary palliative intervention cost US$6,580 less per patient in the last months of life, the equivalent of a 45% cost reduction in the intervention cohort compared to the baseline cohort.Citation20 Among patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), proactive palliative care has been shown to not only decrease costs but also improve mortality.Citation12 The findings within NSCLC are so profound that it is now considered standard of care to include early introduction of palliative care along-side more aggressive treatment.Citation21 The American Thoracic SocietyCitation22 and the recent Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease statementCitation2 have called for increased palliative care services for patients living with COPD but at this time proactive palliative care for patients with COPD is rare and far from standard of care.

The burden of COPD

Not only is COPD a leading case of mortality, it is also a leading cause of disability throughout the world. In 2002 it was ranked as the eleventh leading cause of disability life adjusted years and is projected to increase to the seventh worldwide leading cause by 2030.Citation4 In 2014, a systematic review of the indirect costs of COPD found that 13%–18% of individuals with COPD in the United States reported limitations in their ability to work.Citation21

Across many studies of patients with COPD at the end of life, severe breathlessness is profoundly distressing to patients and is often poorly controlled and under-addressed by care providers.Citation6,Citation12,Citation23,Citation24 In a cross-sectional study evaluating symptom burden in Sweden, approximately 90% of patients with stable lung function report shortness of breath.Citation23 Shortness of breath is not only a distressing symptom to patients but is also associated with decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and a risk factor for further COPD exacerbations and functional decline.Citation12,Citation25

Patients with COPD have a large burden of symptoms beyond breathlessness including fatigue, cough, and pain. Even among patients with minimal decrements in lung function, many report symptoms of cough, dry mouth, and fatigue.Citation8 In the Swedish cross-sectional study, patients with moderate to severe airflow limitations were found to have on average 7.9 symptoms at any given time and patients with severe and very severe airflow limitations typically reported between nine and 14 symptoms.Citation23 In an international survey of 12 countries, 50% of countries reported that the average patient had severe to very severe burden of symptoms when scored with the COPD Assessment Test.Citation24 This burden of symptoms is similar to or worse than that reported in many diseases including NSCLC and heart failure though referral to palliative care subspecialty services is significantly reduced compared to these two conditions.Citation7,Citation8,Citation26,Citation27

Unrecognized and uncontrolled anxiety and depression are major symptoms that impact quality of life in COPD. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among the COPD population varies greatly between studies though is consistently found to be increased compared to other chronic illnesses.Citation26,Citation28 Depression is estimated to be as high as 40% among all stages of COPD and as high as 62% among patients who are prescribed domiciliary oxygen.Citation28,Citation29 Anxiety is similarly found to be as high as 19% across patients with stable COPD though as high as 75% among patients with severe airflow limitation.Citation26 Anxiety and depression are both associated with poor health outcomes including increased frequency of hospital admission, decreased quality of life, and early death.Citation28

The burden of significant symptoms and comorbid health conditions in COPD are comparable or worse than other chronic illnesses including heart failure, HIV, and metastatic cancer. Patients with COPD, however, are less likely to have adequate treatment of symptoms at the end of their life, are more likely to have a decreased HRQoL, and are significantly less likely to receive specialist palliative care referral.Citation7 Patients with COPD are more likely to have aggressive care at the end of life including mechanical ventilation and stays in the intensive care unit compared to those with lung cancer.Citation30 COPD patients are also more likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at the end of life though evidence from the Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Treatments (SUPPORT) showed no difference in preferences for mechanical ventilation or wishes to receive CPR between COPD patients and those with lung cancer.Citation30 Patients with COPD, therefore, are frequently under-supported with significant symptom burden, disability, quality of life impairment, and aggressive use of health care resources at the end of their life.

The current state of COPD and palliative care

Despite refractory symptoms and recurrent hospitalizations, patients with COPD die without access to palliative care.Citation7 Many physicians view palliative care only as care given to actively dying individuals rather than a multidisciplinary approach that focuses on a patient’s quality of life and burden of symptoms as well as a means to provide psychosocial support for patients and their caregivers. Physicians have difficulty predicting which patients are at highest risk of dying and have difficulty discussing these concerns with their patients. Additionally, the current health systems are not designed to adequately reimburse palliative care treatments for patients with COPD. Consequently, patients with COPD are often not referred to palliative care recourses and have unmet needs at the end of life.Citation6,Citation9

This review focuses on the many barriers to providing palliative care including the difficulties of prognostication and communication as well as the obstacles within the current health systems. Although specific pharmacotherapy options for managing symptoms of COPD are outside the scope of this article, this review lays out a new framework for delivery of palliative care. Additionally, this review specifically discusses how to identify patients appropriate for palliative care as well as how to screen for and address the unmet needs of patients with COPD.

Barriers to providing palliative care to patients with COPD

Difficulties of prognosis

The variable and prolonged course of COPD patients makes prognostication difficult for both physicians, patients, and their caregivers, and makes addressing end-of-life goals difficult. Unlike the typical patient with metastatic cancer who classically has a predictable, steady decline after diagnosis, the natural history of COPD is typically protracted and heterogeneous.Citation31 Often, patients are first diagnosed with COPD after developing breathlessness in the outpatient setting. The diagnosis is made with lung function testing though the degree of lung function impairment is often not correlated to the patient’s symptom burden or disease course.Citation2,Citation31 Patients experience a continuous slow decline in lung function accompanied by a slow accumulation of symptoms punctuated by episodes of acute exacerbation and decline with only partial recovery.Citation32

While patients often experience a slow decline in functional status they also suffer episodes of acute exacerbation that may require hospitalization.Citation33,Citation34 Although patients are at high risk of death during and just following these exacerbations, patients will often survive many acute episodes before their time of death.Citation35 The episodic course of COPD makes the exact time of death often feel unexpected and abrupt for both families and physicians since the patient had survived seemingly similar episodes in the past. The SUPPORT study reinforced this finding as it showed that 5 days before death, physicians estimated that their patients with COPD were more than 50% likely to be alive in 6 months.Citation36 Patients with lung cancer, in the same study however, were predicted to be less than 10% likely to be alive in 6 months.Citation36

The difficulty in prognostication causes both patients and physicians to struggle to recognize the terminal phase of illness. For this reason, approaches that limit palliative care resources to the final stages of life overlook many dying patients as their terminal phase of illness goes unrecognized. For this reason, an approach whereby COPD health care providers adopt proactive palliative care that does not rely on the precise prognostication and identification of imminent death in COPD would likely result in greater access to palliative care services for people living with COPD.

Difficulties with communication

Communication is often compromised between patients with COPD and their physicians. Due to the difficulty of prognostication, physicians are often hesitant to discuss their patient’s disease course and expected course of illness.Citation37,Citation38 Physicians also report concern about removing hope for their patient and fear that this will have detrimental effects on their patient’s quality of life (QoL) and mortality.Citation39 Even among physicians who feel their patients would benefit from goals of care conversations, many report inadequate training and insufficient time to approach these conversations.Citation40–Citation42

Patients are also reluctant to discuss the end of their life. Commonly cited barriers include not knowing which physician they should speak to about their wishes, not knowing the extent of their own wishes, as well as wanting to focus on curative treatments instead of thinking about COPD as a life-limiting illness. In a qualitative study of patients with COPD, many were quoted saying “I would rather concentrate on staying alive than talk about death”.Citation39 In review of the Phase II intervention of the SUPPORT trial, only 23% of patients had discussed their wishes regarding CPR before hospitalization. Among patients who had not discussed their preferences, only 42% were interested in doing so leaving a majority of patients, approximately 58%, uninterested in having a conversation regarding CPR preferences. Interestingly, however, 87% of patients who had not and did not want to discuss their preferences wanted to avoid prolonged mechanical ventilation and 25% wanted to avoid resuscitation completely. Additionally, 80% of patients who did not want to discuss their end-of-life wishes also had not completed advanced directives.Citation43 Although patients may not initially be interested in discussing advanced directives with their physicians, this study suggests that many patients still have unexpressed wishes that may not be respected if the conversation is not broached delicately.Citation9,Citation43

Despite the many barriers to communication from both the physician and patient perspective, patients express the desire to have emotional support and discuss end-of-life care with their physicians.Citation44 In particular COPD patients report particular deficits in discussing prognosis as well as the dying process with their physicians.Citation37

Health-systems issues

There is great variability in access to palliative care worldwide. The UK for instance, the founder of the Hospice movement, is rather progressive with one of the highest services to population ratios of 15 services (defined as hospital units, palliative care teams, home care teams etc) per million inhabitants.Citation45 In other parts of the world, however, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, palliative care is thought to be a luxury and not a basic right of an individual and there are no national palliative care services available.Citation46 Even in areas of the world that have well-defined palliative care resources, many are limited to individuals in the terminal phase of illness or limited to particular diagnoses such as cancer,Citation47 making a proactive palliative care approach in a chronic medical condition like COPD challenging. In the USA, current reimbursement structures are set up to fund curative treatment or terminal illness. There are not, however, consistent systems in place to reimburse providers for palliative treatment throughout the course of a patient’s illness or to support the holistic and psychosocial aspects of a patient’s care. Consequently, even if patients and physicians are discussing symptom management, improved home recourses, support for primary caregiver, and long-term care planning, they are often unable to be reimbursed for these extensive recourses and thus are unable to address these unmet needs.Citation48

Palliative care and COPD

Identifying patients appropriate for referral to palliative care: the surprise question

Prognostication of the exact time of death will always be difficult for the clinician and the patient with COPD. When palliative care is included not only during the terminal phase of illness but also during the last few stages of disease, the difficulties of prognostication are often alleviated. One proposed method for identifying patients appropriate for proactive palliative care is the use of “the surprise question”. This method, encourages physicians to ask “would I be surprised if my patient were to die in the next 12 months?”Citation49 If the answer is no, proactive palliative care should be considered.Citation49,Citation50 The “surprise question” has been adopted by the UK national policies to be used as a supplementary screening tool for primary care physicians to identify patients who would benefit from early palliative care.Citation51 It has also been studied in other diseases including end-stage renal disease and has been shown to aid in the prediction of short-term mortality risk in hemodialysis patients.Citation52

Twelve-month predictors of mortality

Many studies have looked into predictors of 12-month mortality as well as predictors of mortality post-hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of COPD. Consistently authors report that patients with advanced age, cardiac comorbidity, low forced expiratory volume in 1 second, low body mass index, poor functional status, and poor HRQoL were at increased risk of dying within the following year.Citation35,Citation53–Citation56 Although each individual’s mortality will vary, identifies flags to recognize patients that would benefit from proactive supportive palliative care interventions.

Table 1 Triggers to begin or intensify proactive palliative resources for patients with COPD

Refractory symptoms

In addition to those patients with high risk of death within the next year of life, patients with symptoms that are refractory to initial therapy would benefit from an early palliative care approach. As discussed earlier, patients with COPD have a multitude of symptoms ranging from dyspnea fatigue, cachexia, anxiety, and depression. Although some patients may respond quickly to pharmacotherapy, opioids, and oxygen therapy, others continue to suffer after initial steps are taken. In these patients, intensive outpatient support that can be provided by a palliative care team should be considered.

New models of care

Though the focus of both inpatient and outpatient palliative care has been on oncology patients, there have been a few studies evaluating palliative care and holistic interventions within the COPD population.

A recent study published in December 2014 was a single-blind randomized controlled trial for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness. In this study both patients with cancer and advanced chronic illness, including COPD, were enrolled and followed for a 6-week intervention. The support services involved a multidisciplinary team including pulmonologists, palliative care specialists, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and occupational therapists. Patients were screened at routine clinic appointments and given a breathlessness pack including medications, a crisis plan, as well as a poem. Patients then received a home assessment 2–3 weeks after enrollment by a physical therapist and occupational therapist and a follow-up appointment with the pulmonologist and palliative care physician at 4 weeks after enrollment. Not surprisingly, patients in the breathlessness support arm of the trial had a significant reduction in their burden of symptoms. Surprisingly, unlike the cancer patients involved in the intervention who had no change in mortality, patients with COPD had a significant mortality benefit upon 6-month follow-up; 100% of COPD patients in the breathlessness support arm were alive at 6 months whereas only 79% were found to be alive in the control cohort.Citation57 Similar mortality benefits were found for all non-oncologic patients in this cohort. This study is the first randomized controlled trial addressing breathlessness through a proactive palliative method in the outpatient setting and suggests that this will not only treat the symptoms of advanced illness but potentially also improve the mortality of patients with COPD.Citation57

Another effective tool has been the use pulmonary rehabilitation (PR). PR has been studied in the stable COPD population as well as in the post-hospitalization of acute exacerbation management where it has been found to be effective at reducing symptoms and re-hospitalization as well as improving HRQoL.Citation58 In many studies PR has also been found to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression by increasing the patient’s functional status and allowing them to engage in their community.Citation59 Although PR is not typically classified as a palliative care measure, it is already addressing many of the unmet needs of COPD patients.Citation46 It is a model of care that already involves a multidisciplinary approach after a vulnerable time in a patient’s illness. PR programs, however, do not typically assess patients for concurrent depression and anxiety and do not routinely engage patients in end-of-life discussions at this time.Citation48 With further resources such as scheduled palliative care visits during PR, this could be an ideal time and place to introduce palliative care to COPD patients.

Conclusion: where to go from here

In order to improve the suffering of end-stage COPD patients, palliative care needs to be incorporated earlier into the trajectory of illness. Currently patients and physicians are waiting until identification of the terminal phase of illness that is often indistinguishable from the slow chronic decline with repeated acute exacerbations characteristic of this disabling disease. Opportunities are missed to decrease disease associated disability and suffering for patients. Instead, patients are left with uncontrolled symptoms, disability, anxiety and depression, and repeated hospitalizations at the end of their life. Proactive palliative care must be incorporated to address the needs of patients during the last few years of life in order to prevent suffering and excess spending at the end of life.

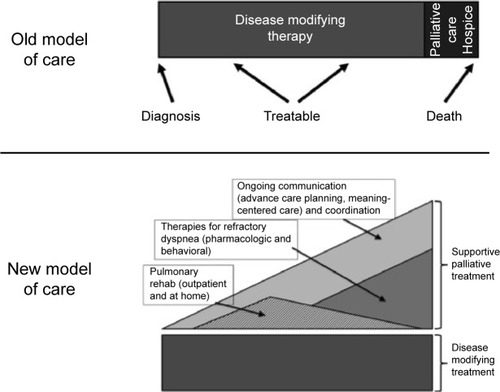

Proactive palliative care should be incorporated early into the patient’s illness as shown in to address complex refractory symptoms, advance care planning, and increase outpatient resources for patients and caregivers. Not all patients who would benefit from proactive palliative support need to be referred to palliative care physicians. Unfortunately given the health systems barriers discussed previously, this will not be feasible in the current system of care in many nations. Instead, primary care providers as well as specialty pulmonologists should be trained and capable of screening patients who would benefit from proactive outpatient supportive care and provide primary palliative care as outlined in . These front-line providers should provide increased focus on symptom management, advance care planning, and support for patients as part of comprehensive COPD care. Interdisciplinary teams including nursing, social work, respiratory, and physical therapists as well as chaplains or pastoral care should be engaged to meet the complex needs of their patients.

Table 2 Primary palliative care

Further research is needed to assess the improvement in patients’ symptoms, QoL and mortality as well as the proposed financial benefits of proactive palliative care in the treatment of COPD. Although we know patients with COPD are suffering and proactive palliative care has been used in other diseases, few research has been performed to prove the benefits of proactive palliative care in COPD. The PROLONG study is an ongoing prospective cluster controlled trial involving six hospitals in the Netherlands using proactive palliative care.Citation60 This will be the first study of its kind to use a proposed set of clinical indicators to prompt proactive palliative care and will assess the effects on mortality and QoL of study participants.Citation60 This is an exciting area of research that will provide new insight into the power of proactive palliative care in COPD.

Disclosure

JH Vermylen and E Szmuilowicz have no disclosures to report in this work. R Kalhan reports personal fees from Forest Laboratories, grants and personal fees from Boerhinger Ingelheim, grants from GlaxoSmithKline and from PneumRx, personal fees from Merck and from Quantia Communications, and grants from Spiration, outside the submitted work.

References

- PettyTLThe history of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061131418046898

- goldcopd.org [homepage on the Internet]Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPDGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2015 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed July 12, 2015

- World Health OrganizationPrevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Guidelines for Primary Health Care in Low Resource SettingsGenevaWorld Health Organization2012 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76173/1/9789241548397_eng.pdfAccessed July 12, 2015

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- JemalAWardEHaoYThunMTrends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002JAMA2005294101255125916160134

- SchroedlCJYountSESzmuilowiczEHutchisonPJRosenbergSRKalhanRA qualitative study of unmet healthcare needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A potential role for specialist palliative care?Ann Am Thorac Soc20141191433143825302521

- GoreJMBrophyCJGreenstoneMAHow well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancerThorax200055121000100611083884

- WalkeLMByersALTinettiMEDubinJAMcCorkleRFriedTRRange and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failureArch Intern Med2007167222503250818071174

- CurtisJRPalliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPDEur Respir J200832379680317989116

- BrumleyREnguidanosSJamisonPIncreased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative careJ Am Geriatr Soc2007557993100017608870

- TenoJMClarridgeBRCaseyVFamily perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of careJAMA20042911889314709580

- TemelJSGreerJAMuzikanskyAEarly palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2010363873374220818875

- LautretteADarmonMMegarbaneBA communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICUN Engl J Med2007356546947817267907

- CasarettDPickardABaileyFADo palliative consultations improve patient outcomes?J Am Geriatr Soc200856459359918205757

- BakitasMLyonsKDHegelMTEffects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trialJAMA2009302774174919690306

- SaundersCThe evolution of palliative careJ R Soc Med200194943043211535742

- World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]WHO Definition of Palliative CareWorld Health Organization2015 Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/Accessed July 12, 2015

- RabowMKvaleEBarbourLMoving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative careJ Palliat Med201316121540154924225013

- RabowMWDibbleSLPantilatSZMcPheeSJThe comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultationArch Intern Med20041641839114718327

- BrumleyRDEnguidanosSCherinDAEffectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-lifeJ Palliat Med20036571572414622451

- SmithTJTeminSAlesiERAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology careJ Clin Oncol201230888088722312101

- LankenPNTerryPBDelisserHMAn official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnessesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177891292718390964

- GreerJAPirlWFJacksonVAEffect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol201230439440022203758

- RabowMWPetersenJSchancheKDibbleSLMcPheeSJThe comprehensive care team: a description of a controlled trial of care at the beginning of the end of lifeJ Palliat Med20036348949914509498

- BlindermanCDHomelPBillingsJATennstedtSPortenoyRKSymptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Pain Symptom Manage200938111512319232893

- SolanoJPGomesBHigginsonIJA comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal diseaseJ Pain Symptom Manage2006311586916442483

- EdmondsPKarlsenSKhanSAddington-HallJA comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancerPalliat Med200115428729512054146

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 Suppl43S56S18842932

- LacasseYRousseauLMaltaisFPrevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2001212808611314288

- ClaessensMTLynnJZhongZDying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of TreatmentsJ Am Geriatr Soc2000485 SupplS146S15310809468

- CasanovaCde TorresJPAguirre-JaimeAThe progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is heterogeneous: the experience of the BODE cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118491015102121836135

- MurraySAKendallMBoydKSheikhAIllness trajectories and palliative careBMJ200533074981007101115860828

- FletcherCPetoRThe natural history of chronic airflow obstructionBr Med J19771607716451648871704

- Sanchez-SalcedoPDivoMCasanovaCDisease progression in young patients with COPD: rethinking the Fletcher and Peto modelEur Respir J201444232433124696115

- SteerJGibsonGJBourkeSCPredicting outcomes following hos-pitalization for acute exacerbations of COPDQJM20101031181782920660633

- No authors listedA controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal InvestigatorsJAMA199527420159115987474243

- CurtisJREngelbergRANielsenELAuDHPatrickDLPatient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPDEur Respir J200424220020515332385

- ChristakisNAIwashynaTJAttitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internistsArch Intern Med199815821238923959827791

- KnauftENielsenELEngelbergRAPatrickDLCurtisJRBarriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPDChest200512762188219615947336

- SullivanAMLakomaMDBlockSDThe status of medical education in end-of-life care: a national reportJ Gen Intern Med200318968569512950476

- ElkingtonHWhitePHiggsRPettinariCJGPs’ views of discussions of prognosis in severe COPDFam Pract200118444044411477053

- MulcahyPBuetowSOsmanLGPs’ attitudes to discussing prognosis in severe COPD: an Auckland (NZ) to London (UK) comparisonFam Pract200522553854016024556

- HofmannJCWengerNSDavisRBPatient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of TreatmentAnn Intern Med199712711129214246

- CurtisJRWenrichMDCarlineJDShannonSEAmbrozyDMRamseyPGPatients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDSChest2002122135636212114382

- CentenoCClarkDLynchTFacts and indicators on palliative care development in 52 countries of the WHO European region: results of an EAPC Task ForcePalliat Med200721646347117846085

- Mwangi-PowellFNPowellRAHardingRModels of delivering palliative and end-of-life care in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review of the evidenceCurr Opin Support Palliat Care20137222322823572158

- Van BeekKWoithaKAhmedNComparison of legislation, regulations and national health strategies for palliative care in seven European countries (Results from the Europall Research Group): a descriptive studyBMC Health Serv Res20131327523866928

- HardinKAMeyersFLouieSIntegrating palliative care in severe chronic obstructive lung diseaseCOPD20085420722018671146

- MurraySABoydKSheikhAPalliative care in chronic illnessBMJ2005330749261161215774965

- SeamarkDASeamarkCJHalpinDMPalliative care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review for cliniciansJ R Soc Med2007100522523317470930

- MurraySBoydKUsing the ‘surprise question’ can identify people with advanced heart failure and COPD who would benefit from a palliative care approachPalliat Med201125438221610113

- Da Silva GaneMBraunAStottDWellstedDFarringtonKHow robust is the ‘surprise question’ in predicting short-term mortality risk in haemodialysis patients?Nephron Clin Pract20131233–418519323921223

- BenzoRSiemionWNovotnyPFactors to inform clinicians about the end of life in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Pain Symptom Manage2013464491499e423522520

- GroenewegenKHScholsAMWoutersEFMortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPDChest2003124245946712907529

- McGhanRRadcliffTFishRSutherlandERWelshCMakeBPredictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPDChest200713261748175517890477

- Bustamante-FermoselADe Miguel-YanesJMDuffort-FalcoMMunozJMortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the burden of clinical featuresAm J Emerg Med200725551552217543654

- HigginsonIJBauseweinCReillyCCAn integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trialLancet Respir Med201421297998725465642

- PuhanMAGimeno-SantosEScharplatzMTroostersTWaltersEHSteurerJPulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201110CD00530521975749

- Paz-DiazHMontes de OcaMLopezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- DuenkRGHeijdraYVerhagenSCDekhuijzenRPVissersKCEngelsYPROLONG: a cluster controlled trial to examine identification of patients with COPD with poor prognosis and implementation of proactive palliative careBMC Pulm Med2014145424690101

- ConnorsAFJrDawsonNVThomasCOutcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments)Am J Respir Crit Care Med19961544 Pt 19599678887592

- FruchterOYiglaMCardiac troponin-I predicts long-term mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCOPD20096315516119811370

- HoTWTsaiYJRuanSYIn-hospital and one-year mortality and their predictors in patients hospitalized for first-ever chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a nationwide population-based studyPloS One2014912e11486625490399

- MatersGAde VoogdJNSandermanRWempeJBPredictors of all-cause mortality in patients with stable COPD: medical co-morbid conditions or high depressive symptomsCOPD201411446847424831411

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchaguenAMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest200212151441144812006426

- GudmundssonGGislasonTLindbergEMortality in COPD patients discharged from hospital: the role of treatment and co-morbidityRespir Res2006710916914029

- WaschkiBKirstenAHolzOPhysical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort studyChest2011140233134221273294

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJPredictors of 1-year mortality in patients discharged from hospital following acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAge Ageing200534549149616107452

- HallinRGudmundssonGSuppli UlrikCNutritional status and long-term mortality in hospitalised patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Respir Med200710191954196017532198