Abstract

Background and objective

The prevalence and mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in elderly patients are increasing worldwide. Low body mass index (BMI) is a well-known prognostic factor for COPD. However, the obesity paradox in elderly patients with COPD has not been well elucidated. We investigated the association between BMI and in-hospital mortality in elderly COPD patients.

Methods

Using the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database in Japan, we retrospectively collected data for elderly patients (>65 years) with COPD who were hospitalized between July 2010 and March 2013. We performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to compare all-cause in-hospital mortality between patients with BMI of <18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 (low–normal weight), 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 (high–normal weight), 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight), and ≥30.0 kg/m2 (obesity) with adjustment for patient backgrounds.

Results

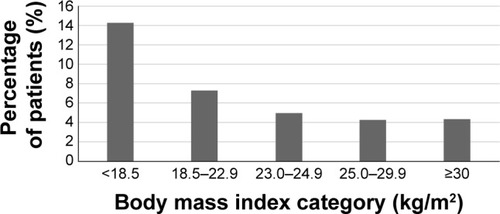

In all, 263,940 eligible patients were identified. In-hospital mortality was 14.3%, 7.3%, 4.9%, 4.3%, and 4.4%, respectively, in underweight, low–normal weight, high–normal weight, overweight, and obese patients. Underweight patients had a significantly higher mortality than low–normal weight patients (odds ratio [OR]: 1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.48–1.63), whereas lower mortality was associated with high–normal weight (OR: 0.76, CI: 0.70–0.82), overweight (OR: 0.73, CI: 0.66–0.80), and obesity (OR: 0.67, CI: 0.52–0.86). Higher mortality was significantly associated with older age, male sex, more severe dyspnea, lower level of consciousness, and lower activities of daily living.

Conclusion

Overweight and obese patients had a lower mortality than low–normal weight patients, which supports the obesity paradox.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a life-threatening lung disease that interferes with normal breathing and is not fully reversible. Worldwide, an estimated 64 million people had moderate-to-severe COPD in 2004, and it caused the deaths of over 3 million individuals in 2005.Citation1 Prevalence and mortality in COPD are higher in older patients,Citation2 and there is an independent association between older patients with COPD and higher mortality.Citation3,Citation4

Low body mass index (BMI) is a potential prognostic factor for short- and long-term mortality in COPD.Citation5–Citation9 However, the relationship between obesity and mortality of COPD is controversial. The obesity paradox, which is based on a protective effect of adipose tissue against mortality, has been observed in various chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease,Citation10 chronic heart failure,Citation11 stroke,Citation12 chronic kidney disease,Citation13 type 2 diabetes mellitus,Citation14 and pulmonary hypertension.Citation15 Further, the obesity paradox has been reported in respiratory diseases,Citation16 and the possibility of an obesity paradox in COPD has been discussed.Citation17,Citation18 However, the obesity paradox in patients with COPD has not been adequately examined. Further, most studies demonstrating the association between low BMI and higher mortality in chronic diseases have been conducted in Western populations. It has been found that Asian populations have a different association between BMI and health risks to Western populations; this is because Asians have a lower mean BMI than non-Asians and Asians have a higher percentage of body fat than non-Asians with a similar BMI.Citation19

Using a nationwide inpatient database, we aimed to evaluate the association between BMI and mortality in elderly patients with COPD in Japan.

Methods

Data source

The Diagnosis Procedure Combination database is a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. The database includes administrative claims data and discharge abstract data. Main diagnosis, comorbidities present on admission, and complications occurring during hospitalization are coded using the International Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes accompanied by text data in Japanese. The database also contains the following details: type of admission (emergent or non-emergent), patient’s age, sex, body height and weight, smoking index (defined as the number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years smoked), severity of dyspnea based on the Hugh-Jones dyspnea scale,Citation20 levels of consciousness based on the Japan Coma Scale,Citation21,Citation22 on admission, activities of daily life on admission converted to the Barthel index,Citation23 intensive care unit admission during hospitalization, use of mechanical ventilation, and discharge status. The grading of dyspnea severity was based on the Hugh-Jones classificationCitation20 and defined as follows: 1) the patient’s breathing was as good as that of other people of their age and build when working, walking, and climbing hills or stairs; 2) the patient could walk at the same pace as healthy people of their age and build on level ground but was unable to maintain that pace on hills or stairs; 3) the patient was unable to maintain the pace of healthy people of their age and build on level ground but could walk about 1.6 kilometers or more at their own speed; 4) the patient was unable to walk more than about 50 meters on level ground without a rest; 5) the patient was breathless when talking or undressing or was unable to leave their home because of breathlessness; and (unspecified) the patient could not be classified into the above grades because of their bedridden status. The numbers of participating hospitals were 980, 1,075, and 1,057, respectively, for July 2010 to March 2011, April 2011 to March 2012, and April 2012 to March 2013.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo. It waived the requirement for patient informed consent because of the anonymous nature of the data.

Patient selection

We retrospectively collected data for patients aged over 65 years who had been admitted to hospital because of COPD (ICD-10 codes J41, J42, J43, J44) as the main diagnosis, or who had been admitted for any cause but had COPD as comorbidity on admission, and were discharged between July 1, 2010 and March 31, 2013. COPD and other comorbidities were based on physician diagnosis.

Comorbidities on admission

The following comorbidities were identified using ICD-10 codes: pneumonia caused by pathogenic microbes (J10–J18); asthma (J45, J46); aspiration pneumonia (J69); interstitial pneumonia (J84); pulmonary embolism (I26); respiratory failure (J96); lung cancer (C34); heart failure (I50); ischemic heart disease (IHD; I20–I22, I25); cardiac arrhythmia (I44, I45, I47–I49); cerebral vascular diseases (I60–I69); chronic liver disease (K70, K71, K73, K74, K76); chronic renal failure (N18); anxiety (F40–F41); depression (F30–F33); and bone fracture (S02, S12, S22, S32, S42, S52, S62, S72, S82, S92, T02, T10, T12).

BMI categories

BMI categories were assigned based on World Health Organization classifications of underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) individuals. Normal weight was further divided into low–normal (18.5–22.9 kg/m2) and high– normal (23.0–24.9 kg/m2).Citation24,Citation25

Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

We used chi-square tests to examine differences in categorical variables. We performed a multivariable logistic regression for in-hospital mortality to analyze patient-level factors associated with the outcome after adjustment for within-hospital clustering by means of a generalized estimating equation.Citation26 For the BMI categories, we defined the low–normal weight group as the reference category. The threshold for significance was P<0.05. We performed all statistical analyses using SPSS software (v20; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Among 19 million patients during the 33 months between July 2010 and March 2013, we found 263,940 patients with COPD who were aged over 65 years. The mean age was 77.8 years (standard deviation [SD]: 7.2), and the proportions of males and females were 80.0% (n=211,057) and 20.0% (n=52,883), respectively. The mean number of smoking pack-years was 55.6 (SD: 35.6). Detailed clinical characteristics and primary diagnoses on admission appear in . shows the patient characteristics divided by BMI category. We observed that the mean age increased with decreasing BMI. The proportion of patients aged over 85 years was higher in the underweight group, but lower in the overweight and obese groups. The percentage of males was higher in the underweight group. The proportion of patients with severe dyspnea (Hugh-Jones class V) was lowest (14.6%) in the overweight group and highest (27.1%) in the underweight group. Disability scores, consciousness levels, and types of admission showed similar patterns to the dyspnea grades.

Table 1 Characteristics and comorbidities in elderly patients with COPD

The percentage of the following comorbidities was higher in the lower BMI categories: pneumonia caused by pathogenic microbes, aspiration pneumonia, respiratory failure, heart failure, and bone fracture. In contrast, the percentage of the following comorbidities was higher in the higher BMI categories: asthma, interstitial pneumonitis, IHD, liver disease, and chronic renal failure. shows all-cause in-hospital mortality for each BMI category. In-hospital mortality was 14.3%, 7.3%, 4.9%, 4.3%, and 4.4%, respectively, in the underweight, low–normal weight, high–normal weight, overweight, and obese groups.

Figure 1 All-cause in-hospital mortality among elderly patients with COPD according to body mass index category.

shows the results of the logistic regression analysis for all-cause in-hospital mortality. The underweight group had a significantly higher mortality than the reference low–normal weight group. The overweight and obese groups had significantly lower mortality rates than the reference group. Older age, male sex, more severe dyspnea scores, lower activities of daily life scores, and lower levels of consciousness were also significantly associated with higher mortality. Emergency admission in elderly COPD patients was likewise associated with high mortality. Regarding pulmonary comorbidities, higher mortality was significantly associated with pneumonia caused by pathogenic microbes, aspiration pneumonia, interstitial pneumonitis, respiratory failure, and lung cancer. With extrapulmonary comorbidities, higher mortality was associated with heart failure, liver disease, chronic renal failure, and bone fracture. Conversely, lower mortality was associated with asthma, IHD, and cerebrovascular diseases. Emergency admission in elderly COPD patients was also associated with high mortality.

Table 2 Multivariable logistic regression analysis for all-cause in-hospital mortality

Discussion

This study used a national inpatient database in Japan to investigate the association between BMI and mortality in 263,940 elderly inpatients with COPD. Underweight patients had a significantly higher mortality than low–normal weight patients, whereas overweight and obese patients showed significantly lower mortality rates. The present study is the first to demonstrate the obesity paradox in all-cause in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with COPD in a nationwide setting.

Previous studies on BMI and COPD mortality have found low BMI to be associated with high mortality in COPD patients.Citation5–Citation9 One limited investigation determined that higher mortality was associated with lower BMI and that mortality decreased with increasing BMI in severe COPD; however, in mild and moderate COPD, the lowest mortality was found in patients with normal BMI.Citation7 Most studies evaluating BMI and mortality in COPD have not examined the association between being overweight or obese and lower mortality in COPD patients. In the present study, higher mortality was associated with underweight, which concurs with the results of previous studies,Citation5–Citation9 which found lower BMI to be associated with higher mortality in COPD. Moreover, we found that lower mortality was associated with overweight and obesity, which supports the obesity paradox in elderly patients with COPD.

Generally, overweight and obesity are well-known risk factors for several chronic diseases and all-cause mortality in healthy individuals. However, one systematic review of cohort studies examined the association between BMI and total mortality in patients with coronary artery disease; it found that compared with normal BMI patients, those with low BMI (<20 kg/m2) had an increased risk for all-cause mortality and that overweight patients (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) had the lowest mortality risk. Obese patients (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) showed no increased risk for total mortality.Citation10 These findings appear to be at variance with the above-mentioned prevailing orthodoxy. Similarly, this paradoxical association between obesity and mortality has been reported for chronic heart failure,Citation11 stroke,Citation12 chronic kidney disease,Citation13 type 2 diabetes mellitus,Citation14 and pulmonary hypertension.Citation15 This phenomenon is referred to as the obesity paradox. However, this paradoxical association between mortality and BMI has not been previously evaluated in COPD patients.

Even though overweight and obesity have not been well-elucidated in COPD patients, there is evidence in the literature that overweight and obesity may be related to poor outcomes with COPD. Overweight and obesity have been reported to be associated with reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and weight gain has been shown to reduce pulmonary function longitudinally.Citation27,Citation28 COPD patients are at increased risk of developing obesity since they have decreased physical activity owing to exertional dyspnea and long-term use of systemic glucocorticosteroids to prevent exacerbation;Citation17 this suggests a potential link between obesity and COPD. Epidemiologically, obesity has been found to be more prevalent in COPD patients than in the general population, and the prevalence of obesity was more frequent in early-stage COPD.Citation17 Thus, the harmful long-term effects related to obesity may result in poor outcomes with COPD. In addition, it has been suggested that obesity is related to systemic inflammation in COPD by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines from adipose tissue and that it contributes to the development of comorbidities and exacerbations in COPD.Citation17,Citation29 Further, insulin resistance, which is a common underlying pathophysiological finding in metabolic syndrome, is reportedly increased in COPD, and it may contribute to systemic extrapulmonary complications, which are linked to systemic low-grade inflammation in COPD patients.Citation30 Therefore, obesity and overweight have been recognized as being associated with the severity of COPD, and obesity and overweight may exert undesirable effects in COPD patients. However, the present study demonstrated that overweight and obese patients had lower mortality rates than those with low–normal weight, which supports the existence of an obesity paradox in elderly patients with COPD.

Some studies have reported a favorable effect of obesity in COPD.Citation31–Citation33 It is reasonable to predict that obese COPD patients are more likely to experience greater dyspnea and exercise intolerance and may have poor prognosis; however, recent evidence suggests that obese COPD patients have similar or better dyspnea scores during exercise and do not have diminished exercise capacity compared with normal-weight COPD patients.Citation32,Citation33 In pulmonary function tests, obese COPD patients had both a reduced end-expiratory lung volume and a preserved inspiratory capacity;Citation31 these are related to dyspnea scores and are favorable prognostic implications for patients with COPD.Citation34 In addition, the annual decline in FEV1 in obese men with COPD was lower than in males with normal BMI; however, this effect was not observed in women, which indicates that obesity and overweight may exert protective effects in the progressive airflow limitation in COPD.Citation35 The precise physiological mechanism of the obesity paradox in COPD remains unknown, though.

IHD is well-known to be a major comorbidity in COPD owing to shared risk factors of smoking and systemic low-grade inflammation.Citation36,Citation37 The prevalence of IHD in COPD patients has been reported to vary between 4.7% and 60%.Citation38,Citation39 In a population-based study, coronary artery disease was found in 7%–13% of patients diagnosed with COPD.Citation40,Citation41 The prevalence of IHD in the present study was 10.9% in elderly COPD patients, and this figure is comparable with that reported in previous studies.Citation40,Citation41 Further, since both IHD and COPD are leading causes of death, the coexistence of IHD and COPD worsens the prognosis for both diseases. It has been reported that COPD is a predictor of cardiovascular disease mortality; in particular, the association between COPD and cardiovascular disease was stronger in adults aged under 65 years.Citation42 This suggests that cardiovascular disease should be evaluated and treated with particular care in younger adults with COPD.

Asthma often coexists with COPD,Citation43 and asthma–COPD overlap syndrome has been investigated.Citation44 Hardin et al demonstrated that patients with that syndrome frequently underwent COPD exacerbation, showed worse health-related quality of life,Citation45 and could have a poorer prognosis than COPD patients without asthma. However, Fu et al found that COPD patients had a poorer prognosis than patients with asthma–COPD overlap syndrome: the former showed decreased lung function and reduced performance in the 6-minute walk test.Citation46 Fu et al discussed the possibility that the overlap syndrome had a protective effect on disease activity; they suggested that less airway reversibility at baseline is associated with the development of irreversible airflow obstruction, which contributes to a poor prognosis.Citation46,Citation47 The present study also demonstrated that elderly COPD patients with asthma had a better prognosis than those with COPD alone; this confirms the better prognosis in elderly patients with asthma–COPD overlap syndrome. The use of inhaled glucocorticosteroids is effective for treating obstructive inflammatory airway diseases and reduced COPD exacerbation; it is recommended that patients with asthma–COPD overlap syndrome be treated with inhaled corticosteroids,Citation44 and thus may have a better prognosis than patients with COPD alone.

Several limitations in the present study should be acknowledged. Since we based the diagnosis of COPD on physician-diagnosed COPD, the accuracy of COPD diagnosis was not confirmed by specialists. However, in actual practice, COPD is not always diagnosed by specialists; thus, data relating to physician-diagnosed COPD, such as those in epidemiological studies and the present study, are a valuable source of information. In addition, since the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database does not include the stages of COPD severity or details of pulmonary function tests, including FEV1 and other indices, the severity of COPD could not be precisely evaluated in this study.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that higher mortality was associated with underweight; lower mortality was associated with overweight and obesity in elderly COPD patients. This supports the existence of the obesity paradox in elderly patients with COPD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation and grant to the Respiratory Failure Research Group), and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Patient’s clinical characteristics

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]Chronic respiratory disease: Burden of COPDWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/index.htmlAccessed September 30, 2014

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- PatilSPKrishnanJALechtzinNDietteGBIn-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med2003163101180118612767954

- SinganayagamASchembriSChalmersJDPredictors of mortality in hospitalized adults with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Am Thorac Soc2013102818923607835

- ConnorsAFJrDawsonNVThomasCOutcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments)Am J Respir Crit Care Med19961544 Pt 19599678887592

- Gray-DonaldKGibbonsLShapiroSHMacklemPTMartinJGNutritional status and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199615339619668630580

- LandboCPrescottELangePVestboJAlmdalTPPrognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916061856186110588597

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2004350101005101214999112

- TsimogianniAMPapirisSAStathopoulosGTManaliEDRoussosCKotanidouAPredictors of outcome after exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gen Intern Med20092491043104819597892

- Romero-CorralAMontoriVMSomersVKAssociation of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studiesLancet2006368953666667816920472

- OreopoulosAPadwalRKalantar-ZadehKFonarowGCNorrisCMMcAlisterFABody mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysisAm Heart J20081561132218585492

- AndersenKKOlsenTSThe obesity paradox in stroke: lower mortality and lower risk of readmission for recurrent stroke in obese stroke patientsInt J Stroke Epub2013312

- KovesdyCPAndersonJEKalantar-ZadehKParadoxical association between body mass index and mortality in men with CKD not yet on dialysisAm J Kidney Dis200749558159117472839

- CarnethonMRDe ChavezPJBiggsMLAssociation of weight status with mortality in adults with incident diabetesJAMA2012308658159022871870

- ZafrirBAdirYShehadehWShteinbergMSalmanNAmirOThe association between obesity, mortality and filling pressures in pulmonary hypertension patients; the “obesity paradox”Respir Med2013107113914623199841

- JeeSHSullJWParkJBody-mass index and mortality in Korean men and womenN Engl J Med2006355877978716926276

- FranssenFMO’DonnellDEGoossensGHBlaakEEScholsAMObesity and the lung: 5. Obesity and COPDThorax200863121110111719020276

- ChittalPBabuASLavieCJObesity paradox: does fat alter outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?COPD Epub2014619

- WHO Expert ConsultationAppropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategiesLancet2004363940315716314726171

- Hugh-JonesPLambertAVA simple standard exercise test and its use for measuring exertion dyspnoeaBr Med J195214749657114896031

- OhtaTWagaSHandaWSaitoITakeuchiKNew grading of level of disordered consiousness (author’s transl)No Shinkei Geka [Neurological surgery]197429623627 Japanese

- TodoTUsuiMTakakuraKTreatment of severe intraventricular hemorrhage by intraventricular infusion of urokinaseJ Neurosurg199174181861984512

- MahoneyFIBarthelDWFunctional evaluation: the Barthel indexMd State Med J196514616514258950

- World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]Global Database on Body Mass IndexWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jspAccessed October 26, 2014

- HasegawaWYamauchiYYasunagaHFactors affecting mortality following emergency admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMC Pulm Med201414115125253449

- HubbardAEAhernJFleischerNLTo GEE or not to GEE: comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and healthEpidemiology201021446747420220526

- BottaiMPistelliFDi PedeFLongitudinal changes of body mass index, spirometry and diffusion in a general populationEur Respir J200220366567312358345

- WiseRAEnrightPLConnettJEEffect of weight gain on pulmonary function after smoking cessation in the Lung Health StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981573 Pt 18668729517604

- FabbriLMRabeKFFrom COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome?Lancet2007370958979779917765529

- BoltonCEEvansMIonescuAAInsulin resistance and inflammation – A further systemic complication of COPDCOPD20074212112617530505

- OraJLavenezianaPOfirDDeesomchokAWebbKAO’DonnellDECombined effects of obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on dyspnea and exercise toleranceAm J Respir Crit Care Med20091801096497119897773

- GuenetteJAJensenDO’DonnellDERespiratory function and the obesity paradoxCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care201013661862420975350

- LavioletteLSavaFO’DonnellDEEffect of obesity on constant workrate exercise in hyperinflated men with COPDBMC Pulm Med2010103320509967

- CasanovaCCoteCde TorresJPInspiratory-to-total lung capacity ratio predicts mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171659159715591470

- WatsonLVonkJMLöfdahlCGEuropean Respiratory Society Study on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseasePredictors of lung function and its decline in mild to moderate COPD in association with gender: results from the Euroscop studyRespir Med2006100474675316199147

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- SinDDManSFWhy are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCirculation2003107111514151912654609

- MullerovaHAgustiAErqouSMapelDWCardiovascular comorbidity in COPD: systematic literature reviewChest201314441163117823722528

- RoversiSRoversiPSpadaforaGRossiRFabbriLMCoronary artery disease concomitant with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur J Clin Invest20144419310224164255

- ErikssonBLindbergAMüllerovaHRönmarkELundbäckBAssociation of heart diseases with COPD and restrictive lung function – results from a population surveyRespir Med201310719810623127573

- SchnellKWeissCOLeeTThe prevalence of clinically-relevant comorbid conditions in patients with physician-diagnosed COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008BMC Pulm Med2012122622695054

- SidneySSorelMQuesenberryCPJrDeLuiseCLanesSEisnerMDCOPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care ProgramChest200512842068207516236856

- GibsonPGSimpsonJLThe overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it?Thorax200964872873519638566

- Global Initiative for Asthma [webpage on the Internet]Asthma, COPD and Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS)Global Initiative for Asthma2014 Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/documents/14Accessed July 27, 2014

- HardinMSilvermanEKBarrRGCOPD Gene InvestigatorsThe clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthmaRespir Res20111212721951550

- FuJJGibsonPGSimpsonJLMcDonaldVMLongitudinal changes in clinical outcomes in older patients with asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndromeRespiration2014871637424029561

- VonkJMJongepierHPanhuysenCISchoutenJPBleeckerERPostmaDSRisk factors associated with the presence of irreversible airflow limitation and reduced transfer coefficient in patients with asthma after 26 years of follow upThorax200358432232712668795