Abstract

Background

In addition to smoking, acute exacerbations are considered to be a contributing factor to progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, these findings come from studies including active smokers, while results in ex-smokers are scarce and contradictory. The purpose of this study was to evaluate if frequent acute moderate exacerbations are associated with an accelerated decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and impairment of functional and clinical outcomes in ex-smoking COPD patients.

Methods

A cohort of 100 ex-smoking patients recruited for a 2-year follow-up study was evaluated at inclusion and at 6-monthly scheduled visits while in a stable condition. Evaluation included anthropometry, spirometry, inspiratory capacity, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, severity of dyspnea, a 6-minute walking test, BODE (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise performance) index, and quality of life (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire and Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire). Severity of exacerbation was graded as moderate or severe according to health care utilization. Patients were classified as infrequent exacerbators if they had no or one acute exacerbation/year and frequent exacerbators if they had two or more acute exacerbations/year. Random effects modeling, within hierarchical linear modeling, was used for analysis.

Results

During follow-up, 419 (96% moderate) acute exacerbations were registered. At baseline, frequent exacerbators had more severe disease than infrequent exacerbators according to their FEV1 and BODE index, and also showed greater impairment in inspiratory capacity, forced vital capacity, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, 6-minute walking test, and quality of life. However, no significant difference in FEV1 decline over time was found between the two groups (54.7±13 mL/year versus 85.4±15.9 mL/year in frequent exacerbators and infrequent exacerbators, respectively). This was also the case for all other measurements.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that frequent moderate exacerbations do not contribute to accelerated clinical and functional decline in COPD patients who are ex-smokers.

Introduction

Progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) assessed by decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) is closely related to active tobacco smoking. It has been shown that smoking cessation decelerates the FEV1 decline in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD.Citation1,Citation2 It is also widely assumed that acute exacerbations contribute to disease progression.Citation3 Exacerbations increase respiratory symptoms, impair exercise capacity, and cause a deterioration in quality of life.Citation4,Citation5 However, most studies evaluating the functional and clinical changes associated with an acute exacerbation and its recovery have included current smokers, making it difficult to separate the effects of exacerbations from those of smoking.Citation3–Citation6 Studies in ex-smokers are scarce and have yielded conflicting results.Citation7–Citation9 Analysis of the Lung Health Study data by Kanner et al indicate that acute exacerbations evaluated by self-reported episodes of lower respiratory infections resulting in physician visits during the previous year in ex-smoking patients do not contribute to FEV1 decline, whereas in a follow-up of 102 patients for 3 years, Makris et al reported that acute exacerbations produced a decline in FEV1 in ex-smokers, albeit of a lesser magnitude that in active smokers.

On the other hand, there is no information about the effect of acute exacerbations on patient-centered outcomes in ex-smoking COPD patients. The aim of the present study was to evaluate if frequent acute exacerbations in ex-smoking COPD patients are associated with disease progression by assessing functional and clinical indices over 2 years of follow-up.

Patients and methods

Patients

A cohort of 105 consecutive ex-smoking patients with a long history of COPD according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteriaCitation10 was enrolled in a 2-year follow-up study, based on scheduled visits every 6 months. Recruitment criteria included: age older than 40 years; smoking history greater than ten packs/year; cessation of smoking for at least 6 months before recruitment, confirmed by urine cotinine levels; absence of an acute exacerbation in the previous month at least; absence of any physical condition precluding the ability to perform a 6-minute walking test (6MWT); or a short life expectancy. Patients with asthma, bronchiectasis, sequelae of tuberculosis, or known malignancy were excluded. The institutional review board at our institution approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Exacerbations

For diagnosis of acute exacerbation, the following definition was applied:

A sustained worsening of the patient’s condition from the stable state and beyond normal day-to-day variation that is acute in onset and necessitates a change in regular medication.Citation11

Patients were instructed to contact one of the investigators if they had an acute increase in symptoms (dyspnea, cough, sputum, and/or purulent sputum) for 2 consecutive days with or without symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection or fever and to attend our clinic to confirm the presence of an acute exacerbation.Citation12

Severity of exacerbation was graded according to the health care utilization classification. Thus, exacerbation was considered: mild if it required increases in regular inhaled medication; moderate if courses of antibiotics and/or systemic corticosteroids were needed; and severe if the patient required hospital admission.Citation13

Exacerbations were treated at our facility or at other health institutions. Those exacerbations treated at other institutions were registered during the scheduled visits, and their severity was categorized according to the treatment received using the above classification.

Measurements

Evaluations were performed at recruitment and at every scheduled visit while patients were in a stable condition. At each visit, assessments included anthropometry, dyspnea, health status, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2), lung function, 6MWT, and comorbidities.Citation14

Magnitude of dyspnea was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council scale (mMRC).Citation15 Lung function included spirometric testing and inspiratory capacity before and after 400 μg of albuterol following international guidelines,Citation16 and was standardized as percentages of predicted values by using prediction equations.Citation17,Citation18 Measurements were carried out by the same laboratory personnel and with the same equipment over the 2 years of follow-up. Health status was assessed with two questionnaires, ie, the Spanish version of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)Citation19 and the Spanish version of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ).Citation20 The 6MWT was measured according to current guidelinesCitation21 and its values were expressed as a predicted percentage using reference values from Troosters et al.Citation22 The BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, exercise performance) indexCitation23 was calculated according to Celli et al. Inhalation therapies were registered at baseline and at each scheduled visit. We considered a drug as being the main therapy if the patients reported its use for at least more than 50% of the follow-up period. Disease progression was assessed by lung function decline and progressive impairment of symptoms, functional capacity (6MWD), health status, and BODE index.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± one standard deviation or median and interquartile range in tables and text, and as the mean ± one standard error in figures. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used for checking distribution normality. Baseline variables were compared by the Student’s t-test for independent samples, the Mann–Whitney U-test, or chi-square test according to the type of variable and its distribution.

For analyses, patients were grouped into two categories according to the annual rate of total number of exacerbations experienced. Since the median exacerbation frequency for the whole group was two per year, those patients experiencing more than the median annual exacerbation rate (two or more acute exacerbations per year) were termed frequent exacerbators whereas those with less than the median were considered infrequent exacerbators.

Differences in changes across time in functional, clinical, and health status indices between infrequent exacerbators and frequent exacerbators were assessed by linear mixed effects models using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM). Using HLM, we examined patterns of change for all measurements (ie, fixed effects) and if there were variations among individuals in these patterns of change (ie, random effects) based on the frequency of exacerbations (ie, covariate). Baseline values for all measurements were used as intercept, allowing us to examine change from these while controlling for the initial values. For these analyses, we used data for all subjects who had at least two measurements. Although linear and quadratic changes were examined (based on number of measures over time), the simplest pattern of change was selected, ie, the most parsimonious model, for further analyses.

All analyses were conducted with the HLM version 6.08 statistical package (Scientific Software International, Inc., Lincolnwood, IL, USA).

Results

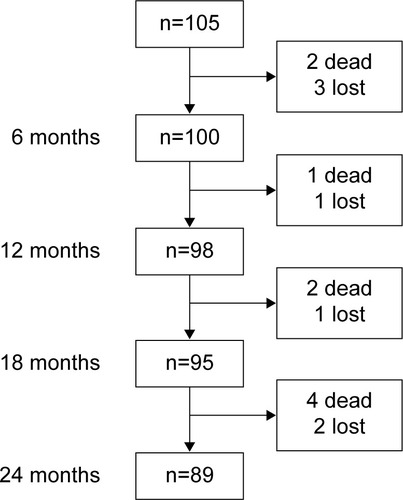

The recruited cohort included 105 patients. Two patients died and another three were lost to follow-up before the first scheduled visit and were consequently excluded from the analyses. During follow-up, seven patients died and four declined to continue in the protocol, mainly due to transport difficulties (). Compared with patients who completed the study, these eleven patients were older, had more severe disease according to GOLD criteria and BODE index, and nine reported frequent exacerbations during the year before recruitment. The baseline characteristics of the 100 patients included in the analyses are shown in .

Table 1 Characteristics of COPD patients at study entry

Number, distribution, and severity of exacerbations

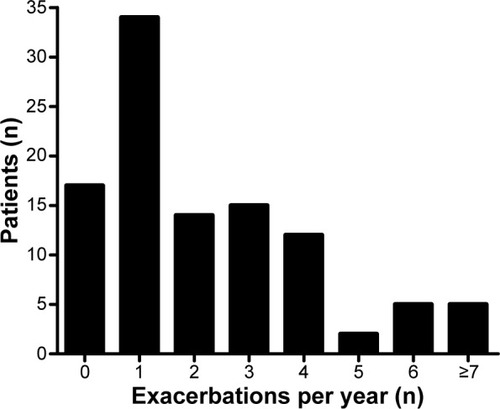

During follow-up, 83 patients had 419 exacerbations. Two hundred and fifty-six patients (61%) were seen and treated at our institution, and the remaining 163 (39%) at other institutions. According to the classification employed, exacerbations were moderate (96%) or severe (4%). Thirteen subjects had one hospitalization, one subject had two hospitalizations, and a third subject had three hospitalizations. The number of exacerbations per patient over the 2 years of follow-up was variable (). Seventeen patients did not experience an exacerbation, whereas five experienced 14 or more exacerbations during the observation period. Median exacerbation frequency was two and one per year in patients classified as frequent exacerbators and infrequent exacerbators, respectively (P<0.001).

Characteristics of patients according to frequency of exacerbations

At baseline, patients with frequent exacerbations showed significant differences in the number of acute exacerbations during the previous year, FEV1 % predicted, forced vital capacity (FVC) % predicted, inspiratory capacity % predicted, and SpO2, as well as a greater impairment in mMRC, health status (SGRQ and CRQ) and the BODE index, as compared with infrequent exacerbators (see ).

Table 2 Baseline characteristics according to frequency of exacerbations in 100 patients with COPD

The slopes for all these variables, representing changes over the 2-year follow-up period, were not significantly different between the two groups (). Thus, FEV1 decreased 57±13 mL/year (1.7% predicted/year) and 85±15.8 mL/year (2.8% predicted/year) in frequent exacerbators and infrequent exacerbators, respectively.

Table 3 Slopes of all indices according to the random effect modeling

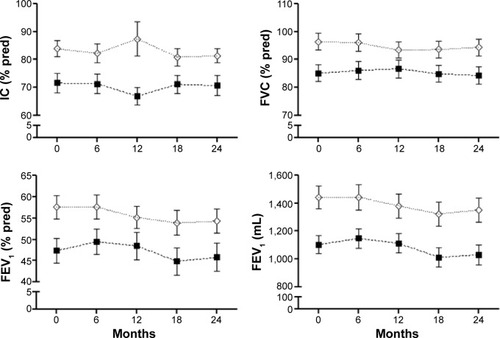

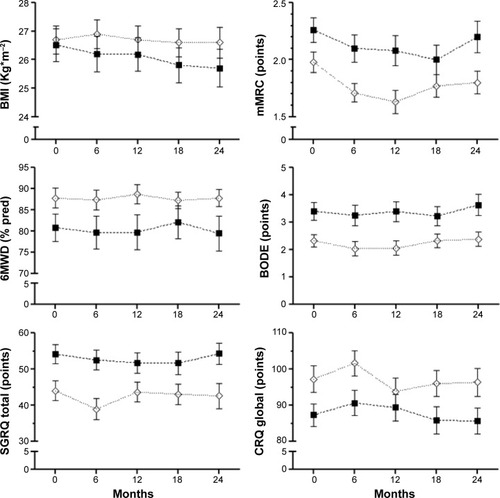

shows lung function indices at baseline and at each scheduled visit in both groups of patients. Over the study period, frequent exacerbators had consistently lower values for inspiratory capacity, FVC, FEV1, and FEV1/FVC than infrequent exacerbators, but changes across time did not differ between the two groups. Similar behavior was observed for functional exercise capacity (6MWT) and health-related quality of life ().

Figure 3 Lung function indices progression.

Notes: Baseline (0) and scheduled visits (every 6 months) during 2 years of follow-up; values are expressed as the mean ± one standard error. (⋄) indicates infrequent exacerbators; (■) indicates frequent exacerbators.

Abbreviations: IC, inspiratory capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; pred, predicted.

Figure 4 Clinical indices and health status progression.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; 6WD, 6-minute walking distance; BODE, body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, exercise performance; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; CRQ, Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire.

Patients with frequent exacerbations were treated more frequently with inhaled corticosteroids, whereas short-acting bronchodilators were used as the main therapy more often by infrequent exacerbators ().

Table 4 Inhaled treatment during follow-up

Discussion

The main findings of this prospective observational study in patients with COPD who had quit smoking and were followed up for 2 years are: frequent moderate exacerbations did not accelerate the decline in FEV1 nor worsen other functional indices as compared with infrequent exacerbations, and there were no significant differences in patient-centered outcomes over time between the two groups. Our results also confirm that exacerbations are more frequent in patients with more severe disease and that previous history of exacerbations is a predictor of frequent exacerbations.Citation24

To our knowledge, this is the first study performed solely in ex-smoking COPD patients that included several clinical indices in addition to lung function to evaluate the effect of exacerbations on disease progression. Our findings are consistent with results reported in other studies, where no significant differences were found in the FEV1 decline between frequent and infrequent exacerbators.Citation4,Citation7,Citation9,Citation25,Citation26 Some of these studies included current smokers.Citation4,Citation25,Citation26 Two studies have previously assessed the effects of exacerbations on FEV1 decline in ex-smokers, with conflicting results.Citation7,Citation9 Kanner et al performed a secondary analysis of the Lung Health Study and found that, in intermittent and continuous smokers, frequent lower respiratory infections were associated with a greater 5-year averaged annual rate of FEV1 loss (−52 mL/year and −69 mL/year, respectively) than in sustained quitters (−12 mL/year). Makris et al evaluated the effect of acute exacerbations in current and ex-smokers during a 3-year prospective study including 58 ex-smokers and 44 current smokers. The FEV1 decline was greater in current smokers than in ex-smokers.

Our results are in agreement with those of the ex-smoker group reported by Kanner et al but differed from those reported by Makris et al. This may be explained by differences between the present study and the study by Makris et al with regard to the number of ex-smoking patients (100 versus 58, respectively) and length of follow-up (2 versus 3 years, respectively), but mainly in the annual rate of hospitalizations (0.10 versus 0.35 per year, respectively), indicating more severe exacerbations in their study.

The effect of exacerbations on decline in lung function has not been clearly established. The role of exacerbation frequency in FEV1 decline is largely based on findings of studies that have included active smokers.Citation3–Citation6 Even so, differences in FEV1 decline between frequent exacerbators and infrequent exacerbators have been small: 8 mL/year was reported by Donaldson et al in a group of 32 patients followed for 4 years and, according to Makris et al frequent exacerbations added −1.4% predicted/year to FEV1 decline.

In the present study, which included only ex-smoking patients, the decline in FEV1, although not significant, was smaller in frequent exacerbators (54.7 mL/year) than in infrequent exacerbators (85.4 mL/year). This unexpected nonsignificant faster decline in infrequent exacerbators could be explained by their higher baseline FEV1 value, in agreement with previous data from Casanova et al.Citation27 It is also consistent with the findings from the analysis of data obtained from the placebo arms of several recent clinical series by Tantucci and Modena,Citation28 which showed that “the loss of lung function, assessed as expiratory airflow reduction, seems more accelerated and therefore more relevant in the initial phases of COPD”. Other possible explanations for the lack of a more rapid FEV1 decline in frequent exacerbators are frequent treatment with systemic corticosteroids due to acute exacerbations as well as more regular use of inhaled corticosteroids than in infrequent exacerbators. Moreover, the effects of acute exacerbations on FEV1 decline are difficult to assess due to the heterogeneity of the patient behavior over time. Several recent studies, independent of the frequency of exacerbations, show a heterogeneous FEV1 decline in COPD.Citation29–Citation31 According to these studies, FEV1 may remain stable in some patients, increase in others, or experience a slow or accelerated decline. Accelerated FEV1 decline was associated with a high baseline FEV1, low body mass index, active smoking, bronchodilator reversibility, and greater magnitude of emphysema. Our results confirm the heterogeneous FEV1 decline reported by these authors, independently of the frequency of exacerbations.Citation29–Citation31

In addition to the lack of effect of acute exacerbations on FEV1 decline, the present results also demonstrate no effects on other physiological or clinical outcomes in ex-smoking COPD patients. To our knowledge, the effects of exacerbations on patient-centered outcomes in ex-smoking COPD patients have not been previously assessed. The few data available derive from the study by Cote et alCitation4 in a cohort of 205 patients (95% men), including active smokers, who were followed for 2 years after their first acute exacerbation. Although no significant changes in FEV1 decline were observed, they found a significant deterioration of mMRC, 6MWT, and BODE index in their frequent exacerbators. In addition to differences in cohort characteristics, our results differ from theirs in the percentage of patients who required hospital admissions. Fifty of their patients with frequent acute exacerbations were hospitalized, of whom 39% required one hospitalization, 35% required two hospitalizations, and 26% required three or more hospitalizations. In our cohort, 13 patients required hospitalization and only four of them required a second hospitalization. As it is known that severe acute exacerbations contribute to deterioration and mortality in COPD patients,Citation32 the greater number of patients and hospital admissions reported by Cote et alCitation4 may explain the clinical deterioration of their patients.

The most advanced therapy (long-acting muscarinic antagonist + long-acting beta-2 agonists + inhaled corticosteroids), mostly received by the frequent exacerbators given their greater COPD severity, could partly explain the lack of significant differences in the measured indices.

Our study has some limitations: the sample size was relatively small; most exacerbations were moderate and treated in an outpatient setting; severe exacerbations, which are known to contribute to mortality and hospitalization, were infrequent; no mild acute exacerbations, ie, those needing only an increase in bronchodilator therapy, were registered, probably because they resolved without medical assistance; and follow-up was relatively short. However, we believe that these limitations do not affect our main findings, indicating no effect of moderate acute exacerbations on FEV1 decline or clinical progression of COPD in ex-smokers.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that acute moderate exacerbations in ex-smoking patients do not contribute to COPD progression assessed by FEV1 decline and by the BODE index during a follow-up of 2 years. They also confirm that changes in FEV1 over time are heterogeneous independent of exacerbation frequency. Although patients with frequent exacerbations had greater baseline impairment of functional and clinical indices than those with infrequent acute exacerbations, their parameters behaved similarly over time. Replication of these findings may help us to better understand how the effects of frequency of exacerbations among ex-smoking COPD patients impacts their disease behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from FONDECYT (1085268).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FletcherCPetoRThe natural history of chronic airflow obstructionBMJ19771607716451648871704

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEMurrayRPSmoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 yearsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166567567912204864

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTABhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2002571084785212324669

- CoteCGDoderllyLJCelliBRImpact of COPD exacerbations on patient-centered outcomesChest2007131369670417356082

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCPaulEABestallJCJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981575 Pt 1141814229603117

- HalpinDMGDecramerMCelliBRKestenSLiuDTashkinDPExacerbation frequency and course of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012765366123055714

- KannerREAnthonisenNRConnetJEfor the Lung Health Study Research GroupLower respiratory illnesses promote FEV1 decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Results from the Lung Health StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001164335836411500333

- SilvermanEKExacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Do they contribute to disease progression?Proc Am Thorac Soc20074858659018073387

- MakrisDMoschandreasJDamaniakiAExacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: new insights in current and ex-smokersRespir Med200710161305131217112715

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- Rodríguez-RoisinRTowards a consensus definition for COPD exacerbationsChest20001175 Suppl 2398S401S10843984

- AnthonisenNRManfredaJWarrenCPWHershfieldESHardingGKMNelsonNAAntibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med198710621962043492164

- WedzichaJASeemungalTCOPD exacerbations: defining their cause and preventionLancet2007370958978679617765528

- CharlsonMSzatrowskiTPPetersonJGoldJValidation of a combined comorbidity indexJ Clin Epidemiol19944711124512517722560

- MahlerDWellsCEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVStandardization of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- HankinsonJLOdencrantzJRFedanKBSpirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S populationAm J Respir Crit Care Med199915911791879872837

- LisboaCLeivaAPinochetRRepettoPBorzoneGDiazOValores de referencia de la capacidad inspiratoria en sujetos sanos no fumadores mayores de 50 añosArch Bronconeumol2007439485489 Spanish17919414

- QuirkFHJonesPWBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self complete measure for chronic airflow limitation: the St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- WilliamsJESinghSJSewellLGuyattGHMorganMDDevelopment of a self-reported chronic respiratory questionnaire (CRQ-SR)Thorax2001561295495911713359

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function LaboratoriesAmerican Thoracic Society Statement. Guidelines for the six-minute walk testAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166111111712091180

- TroostersTGosselinkSDecramerMSix minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjectsEur Respir J199914227027410515400

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2004350101005101214999112

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoAfor the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsSusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- MiratvillesMFerrerMPontAEffect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 2 years follow up studyThorax200459538739515115864

- SpencerSCalverleyPMABurgePSJonesPWImpact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPDEur Respir J200423569870215176682

- CasanovaCCoteCGMarinJMThe six-minute walk distance: long term follow up in patients with COPDEur Respir J200729353554017107991

- TantucciCModenaDLung function decline in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20127959922371650

- CasanovaCde TorresJPAguirre-JaimeAThe progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is heterogeneous. The experience of the BODE cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118491015102121836135

- VestboJEdwardsLDScanlonPDfor the ECLIPSE InvestigatorsChanges in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPDN Engl J Med2011365131184119221991892

- NishimuraMMakitaHNagaiKfor the Hokkaido COPD Cohort Study InvestigatorsAnnual change in pulmonary function and clinical phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121851445222016444

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SanchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbation and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622