Abstract

COPD is a long-term condition associated with considerable disability with a clinical course characterized by episodes of worsening respiratory signs and symptoms associated with exacerbations. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common gastrointestinal conditions in the general population and has emerged as a comorbidity of COPD. GERD may be diagnosed by both symptomatic approaches (including both typical and atypical symptoms) and objective measurements. Based on a mix of diagnostic approaches, the prevalence of GERD in COPD ranges from 17% to 78%. Although GERD is usually confined to the lower esophagus in some individuals, it may be associated with pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents. Possible mechanisms that may contribute to GERD in COPD originate from gastroesophageal dysfunction, including altered pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter (which normally protect against GERD) and changes in esophageal motility. Proposed respiratory contributions to the development of GERD include respiratory medications that may alter esophageal sphincter tone and changes in respiratory mechanics, with increased lung hyperinflation compromising the antireflux barrier. Although the specific cause and effect relationship between GERD and COPD has not been fully elucidated, GERD may influence lung disease severity and has been identified as a significant predictor of acute exacerbations of COPD. Further clinical effects could include a poorer health-related quality of life and an increased cost in health care, although these factors require further clarification. There are both medical and surgical options available for the treatment of GERD in COPD and while extensive studies in this population have not been undertaken, this comorbidity may be amenable to treatment.

Keywords:

Introduction

COPD is a chronic, progressive condition, characterized by an increased inflammatory response within the airways and airflow limitation that is not fully reversible.Citation1 The clinical profile is frequently punctuated by acute exacerbations,Citation2 which increase the risk of morbidity and mortality of COPDCitation3 and are linked to worsening quality of life and accelerated decline in lung function.Citation4 The prevalence of COPD is continually rising,Citation5 particularly in those aged 65 years and older. Accompanying the clinical profile of COPD is a range of comorbidities, which have the potential to complicate the clinical presentation of this condition and may influence morbidity and mortality.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) develops when the reflux of gastric contents results in troublesome symptoms or complications.Citation6 It is a common upper gastrointestinal condition, affecting up to 33% of the general populationCitation7 and may be associated with either esophageal or extra-esophageal syndromes.Citation6 Refluxate may be acidic or nonacidic (alkaline), liquid, or gaseous.Citation8 The frequency and duration of episodes of reflux as well as the destination of the gastroesophageal refluxate affect the impact of GERD.

As both GERD and COPD are highly prevalent conditions, the possibility of an interaction has long been recognized.Citation9–Citation12 With the potential for GERD to aggravate the clinical status of COPD and of the mechanical changes associated with COPD to exacerbate GERD, it is important to understand the relationship and possible consequences of the two conditions co-occurring. This review will explore the underlying pathophysiology of GERD, the commonly applied diagnostic tools, its prevalence and clinical presentation as well as risk factors, and current management strategies.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Pathophysiology

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a normal physiological occurrence, and the integrity of the gastroesophageal junction influences the occurrence and frequency of GER events. Physiologically, there are four causes of GER of gastrointestinal origin. The most common trigger is transient, spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES),Citation13 which may occur in both an upright or recumbent positionCitation14 and promotes reflux. GER may also occur due to diminished basal LES pressure,Citation15 as a result of straining or free reflux. Strain-induced reflux occurs when a hypotensive LES is overcome by an abrupt increase in intra-abdominal pressure (eg, during bending).Citation16 Free reflux occurs when the basal LES pressure is within 1–4 mmHg of the intragastric pressure; this small pressure gradient heightens the likelihood of GER.Citation15 A hiatus hernia is displacement of the gastroesophageal junction above the diaphragm.Citation17 The pressure gradient between the thorax and the abdomen promotes the movement of gastric contents into the esophagus.Citation18 Transient LES relaxations are more likely to be followed by GER episodes in the presence of a hiatus hernia. Normally, esophageal peristalsis facilitates esophageal clearance following reflux episodes.Citation19 Peristaltic dysfunction, with absent or low-amplitude contractions in the distal esophagus, which can be detected through manometry studies, contributes to prolonged esophageal clearance, which increases the chance of reflux.Citation20 The diagnosis of GERD should be considered when symptoms associated with these physiological changes are reported by the patient.Citation6

Changes in LES tone are often triggered by lifestyle factors such as stress or by the consumption of specific foods, including products high in fat (delayed gastric emptying) or those that lower the LES pressure (chocolate, peppermint, onion, garlic, caffeine, and alcohol).Citation21 Eating or drinking acidic foods (tomato products, citrus, and carbonated beverages) may trigger symptoms.Citation21 Other lifestyle factors include sleeping in a supine position or consumption of a meal immediately before sleeping; both may be linked to nocturnal awakening from symptoms.Citation21

Clinical presentation

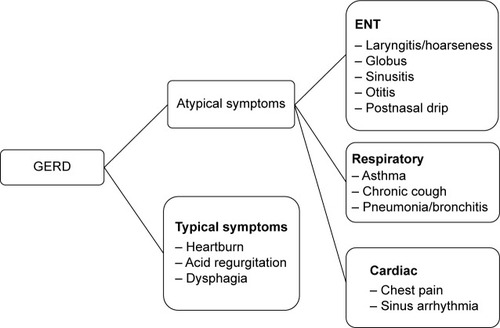

Typical symptoms of GERD include heartburn, acid regurgitation,Citation22 chest pain,Citation23 epigastric pain, or sleep disturbances.Citation6 These clinical features together with esophageal complications, including reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma are collectively referred to as esophageal syndromes.Citation24 Symptoms such as chronic cough or laryngitis that occur secondary to reflux are classed as extra-esophageal syndromes. An outline of typical and atypical clinical presentations of GERD is presented in . Either may be present in COPD.

Diagnostic tools

Diagnosis of GERD

The most common approach to the diagnosis of GERD is through an accurate medical history, enquiring about typical GERD symptoms and their relationship to food, posture, and stress.Citation21 It is important to be aware that symptoms of GERD may be similar to some symptoms of COPD. Therefore, it is necessary to enquire as to the timing of the GERD symptoms and their association with awakening from sleep, the use of respiratory inhalers in association with GERD symptoms, or the presence of respiratory symptoms after meals. Further evaluation may include symptomatic assessment through validated questionnaires, which ideally incorporate both typical and atypical symptoms.Citation25,Citation26 In the presence of symptoms, an empirical trial of acid suppression therapy is often undertaken, with resolution of symptoms considered clinically indicative of GERD, provided the patient has been symptomatic.Citation27 If symptoms are present, objective tools such as esophageal endoscopy may be used to identify secondary complications of mucosal injury and esophagitis.Citation28,Citation29

If asymptomatic reflux is suspected, alternative options for diagnosing GERD include ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. This is the current “gold standard” for diagnosing GERD.Citation30–Citation33 Dual-channel monitoring measures proximal and distal esophageal pH, giving a comprehensive profile of GERDCitation34 using well-defined criteria.Citation31,Citation35 Via a small catheter positioned in the esophagus, this technique measures the esophageal luminal pH. The frequency and duration of reflux episodes and the proximal spread of the refluxate over a complete circadian cycle are quantified.Citation35 For distal GERD, sensitivity ranges from 81% to 96% with specificity from 85% to 100%.Citation30–Citation33 For proximal GERD, the sensitivity ranges from 55% to 86%, although the specificity is slightly higher (80%–91%).Citation36,Citation37 A variation on this is telemetry capsule pH monitoring, which offers increased patient tolerability and the option to extend the monitoring period to 48 hours or 96 hours.Citation38 With the identification of both acid and nonacid reflux, together with the mixture of gas and liquid reflux, combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring records GERD at all pH levels.Citation39 It quantifies volume and gas reflux and the air–liquid composition of the refluxate, giving an exact assessment of the proximal extent of refluxed material and a detailed characterization of each reflux episode.Citation8,Citation39,Citation40

Diagnosis of pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents

Pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents can be detected through various methods. Proximal esophageal pH monitoring has been considered a surrogate marker.Citation10,Citation41,Citation42 One of the more novel measures of pulmonary microaspiration is the measurement of pepsin in airway samples. Pepsin is secreted by cells unique to the gastric mucosa as pepsinogen I or IICitation43,Citation44 and requires acidic conditions to be converted to active pepsin. The detection of pepsin in pulmonary secretions is suggested to indicate pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents.Citation45 Pepsin has been detected in bronchoalveolar lavage of lung transplant recipients who demonstrated GERD on esophageal pH monitoring or impedance monitoringCitation45–Citation48 and more recently in sputumCitation44,Citation49 and exhaled breath condensate (EBC)Citation50 in individuals with COPD. EBC is a sample of breath water vapor containing pulmonary epithelial lining fluid. Acidification of the hypopharynx can occur when gastric contents reach beyond the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), which can be reflected by the presence of pepsin or lower pH levels in EBC.Citation51

Prevalence of GERD in COPD

The prevalence of GERD in individuals with COPD has been explored in a number of studies.Citation11,Citation41,Citation42,Citation49,Citation52–Citation57 A range of diagnostic tools have been used, including symptom questionnaires and objective measurements, outlined in . Based on self-reported symptoms and questionnaires, the prevalence of GERD ranges from 17% to 54%.Citation12,Citation52–Citation55,Citation57–Citation61 Variation is partially attributable to the heterogeneity of questionnaire content. However, while typical GERD symptoms exhibit a sensitivity of 90%, the specificity is as low as 47%,Citation10 which may limit their diagnostic value.

Table 1 Diagnostic approaches and prevalence of GERD in COPD

By comparison, according to esophageal pH monitoring, the prevalence ranges from 19% to as high as 78%.Citation11,Citation41,Citation42,Citation49,Citation56,Citation62,Citation64 Such a wide spread is related to several factors, including the differing GERD criteria appliedCitation31,Citation34,Citation65,Citation66 and whether the test was undertaken on or off antireflux medication. Mixed patterns of reflux are evident, with distal reflux only, proximal reflux only, and a mix of both demonstrated.Citation11,Citation49,Citation56,Citation62 In those with COPD, the prevalence is five times greater than the non-COPD population for proximal and distal reflux.Citation7,Citation67 GERD can affect patients with moderate to very severe COPD.Citation41,Citation42,Citation49,Citation56,Citation62,Citation68 Although a detailed clinical history of symptom presentation is recommended,Citation69 this method of diagnosis is reliant upon the provocation of symptoms by reflux events, which in the event of asymptomatic (clinically silent) reflux is not a reliable indicator. The presence of asymptomatic reflux (20%–74%) in COPDCitation11,Citation41,Citation49,Citation56,Citation62 emphasizes the importance of objective confirmation of GERD in some individuals.

The cause and effect relationship between COPD and GERD has been reported through case–control and cohort studies. El-Serag and SonnenbergCitation70 in a case–control study found that a higher risk of esophageal disease was evident in those with COPD compared to controls (odds ratio [OR] 1.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.33–1.53).Citation70 A recent longitudinal cohort study followed two groups of patients, those diagnosed with GERD with no previous history of COPD and those diagnosed with COPD with no history of GERD over 5 years.Citation71 In those with GERD, the incidence of COPD was with a risk ratio of 1.17 (95% CI 0.91–1.49). In those with COPD, the incidence of GERD was 14.9 cases per 1,000 (95% CI 13.9–16.0), with a relative risk of 1.49 (95% CI 1.19–1.78). While this suggests that a diagnosis of COPD may predispose patients to developing symptoms of GERD, the reasons require further clarification.

One possible explanation is the effect of smoking, and in particular, nicotine on esophageal sphincter tone and esophageal clearance. Smoking has been associated with a reduction in LES tone, believed to be secondary to nicotine-induced relaxation of the circular muscle of the LESCitation72 and reflected by the increased acid exposure in the upright position and an increased frequency of reflux events >5 minutes in duration.Citation73 Prolonged acid clearance secondary to diminished salivation, which may persists for >6 hours after smoking, has also been reported to result in reduced neutralization of esophageal reflux by swallowed saliva.Citation72 With nicotine levels persisting for at least 6 hours after smoking, the implication is that the drug effect may last for a similar duration.Citation72 A higher severity of GERD has been demonstrated in those with COPD who have a high smoking index,Citation64 and pack-years has been found to be an independent risk factor for GERD (OR 1.015 [95% CI 1.004–1.025]).Citation74 Smoking is a risk factor for GERD in the general population,Citation75 and this together with smoking being a leading cause of COPDCitation76 suggests that smoking and the associated effects of nicotine may contribute to GERD in COPD.

Presence of pulmonary microaspiration in GERD

Surrogate indicators of pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents have been examined in COPD. Pepsin in sputum samples was detected in 33% of individuals with moderate-to-severe COPD.Citation49 Although no significant association between esophageal pH monitoring indices and pepsin concentrations in sputum was evident, this has been previously observed in individuals with other types of lung disease.Citation44,Citation46,Citation77,Citation78 Briefly, isolated reflux events that could be aspirated may be insufficiently frequent to contribute to the criteria defining GERD. Laryngopharyngeal reflux, based on laryngeal examination and symptom questionnaires, has also been detected in 44% of individuals with COPD.Citation79 A pilot study of EBC in ten individuals with COPD found pepsin in 70%, irrespective of a diagnosis of GERD based on esophageal pH monitoring.Citation80 Lower EBC pH has been related to severe GERD symptoms in COPD,Citation52 although there was no significant correlation between EBC pH and sputum inflammatory indices (tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-8). This suggests that EBC pH may reflect acid reflux rather than tracheobronchial inflammation. Greater clarity is required to determine the optimal frequency and timing of EBC collection necessary for it to be included as an index of acid reflux.

Possible contributing factors to GERD in COPD

Gastroesophageal mechanisms

A number of possible mechanisms originating from a gastrointestinal or respiratory perspective may increase the vulnerability to GERD in those with COPD. Although esophageal motility studies have not been extensively applied, reduced daytime and nocturnal esophageal peristalsisCitation40,Citation56,Citation81 and a decrease in UESCitation82,Citation83 and LES pressure has been demonstrated in those with severe COPD.Citation11,Citation40,Citation64,Citation82 Change in LES pressure may be partially attributed to smoking and the effects of nicotine.Citation72

Other possible explanations for pulmonary aspiration secondary to GERD are related to swallowing dysfunction in COPD. Precise coordination between swallowing and respiration is necessary, with the swallowing reflex an important defense against airway infection and aspiration.Citation83 Compared to healthy controls, the swallowing reflex can be impaired in COPD,Citation84 with a lack of coordination of the pharyngeal musculature and disruption of the breathing–swallowing coordination.Citation85–Citation87 Patients are more likely to swallow during inhalation or inhale directly after swallowing, as respiratory requirements take precedence over swallowing.Citation85 Low subglottic air pressure occurs during early inhalation, late exhalation, or at the transition point between exhalation and inhalation. If swallowing takes place during times of subglottic air pressure, the physiology of swallowing can also be altered. If the preferred pattern of exhale–swallow–exhale is altered, the risk of aspiration increases.Citation86 This may be a contributing factor to exacerbations of COPD, illustrated by a greater frequency of annual exacerbations (OR 4.86 [95% CI 1.45–18.43]) in individuals with an abnormal swallowing reflex.Citation83 In turn, exacerbations of COPD, with altered respiratory demands, may increase the risk of further aspiration.Citation86

Respiratory mechanisms

Both alterations in respiratory mechanics and side effects of respiratory medications could contribute to GERD. Severe hyperinflation requires increased respiratory muscle inspiratory effort to overcome the increased inspiratory load at high lung volume. The resulting increase in negative pressure amplifies the pressure gradient between the thorax and abdomen, which impacts on LES tone and predisposes to reflux.Citation88,Citation89 This may be especially present during COPD exacerbations when reductions in airflow together with increased coughing impact on this pressure gradient. Airflow obstruction significantly increases the frequency of transient LES relaxation, a mechanism documented in asthma.Citation90 In stable COPD, although differences in lung mechanics between those with and without GERD were not apparent,Citation11 a negative correlation between LES and UES pressure and indices of hyperinflation has been described.Citation64 To date, the association between airway obstruction and LES relaxation requires further clarity.Citation90 The reduction in LES tone secondary to smoking together with coughing, a common symptom of COPD, may predispose some individuals with COPD to strain-induced acid reflux.Citation72 Heightened anxiety is known to aggravate GERD symptoms by increasing acid production.Citation91 As increased anxiety is common in COPD,Citation1 this may be an additional contributory factor to GERD.

Respiratory medications

Respiratory medications, including beta agonists, anticholinergics, corticosteroids, and theophylline preparations have been proposed as possible factors that may be related to GERD.Citation53,Citation92–Citation98 While these medications may alter esophageal function by reducing LES pressure or esophageal motility,Citation92–Citation94 their specific contribution to the risk of GERD is variable. Some studies observed that a greater proportion of individuals with COPD (stable or those at risk of an exacerbation) and GERD were prescribed inhaled corticosteroids, short-and long-acting beta2 agonists, and combination therapy (inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting beta2 agonists);Citation53,Citation59 others found no difference in the prescription of these respiratory medication classes and the presence/absence of GERD.Citation12,Citation54,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60,Citation74 Although it has been hypothesized that these classes of medications may contribute to GERD, the nature of this relationship in COPD has not been fully determined. An increased use of anticholinergics in those with COPD and GERD has been reported by Garcia Rodriguez et alCitation71 while another study found no difference.Citation94 Although central and peripherally acting anticholinergics can reduce LES pressure, their antitussive effect can encourage cough suppression and may minimize the occurrence of changes in intra-abdominal pressure, which may predispose GERD.Citation94 It has been suggested that those with GERD may require more intense bronchodilator therapy secondary to increased severity of respiratory symptoms and exacerbations.Citation53 The increased use of bronchodilator therapy when reflux symptoms are experienced lends support to a possible association between reflux events and worsening symptoms.Citation12 The association between GERD and respiratory medications may also be a reflection of the severity of lung disease rather than the specific physiological effects of these medications on esophageal function. Further exploration of the cause and effect relationship between respiratory medications and GERD in COPD is warranted.

Non-COPD specific factors

A mix of demographic factors may increase the risk of GERD in COPD. Older age (>60 years) is often a factor,Citation53,Citation58,Citation64,Citation95,Citation99 with an increased risk (OR 3.7 [95% CI 2.4–5.9]) reported in those over 70 years.Citation71 Given the high proportion of COPD patients aged over 65 years, this finding is not surprising. The contribution of sex is variable, with some studies finding females at greater risk,Citation53 others demonstrating that GERD is more common in malesCitation71 and some finding no difference.Citation54,Citation58 This is consistent with studies of GERD among the general populationCitation100,Citation101 and leaves open the influence of sex as an independent risk factor for GERD.

A larger body mass index (BMI; >25 kg/m2 – classed as overweight) has been identified as a risk for GERD in COPD,Citation53–Citation56,Citation58,Citation64 a risk which increases as BMI increases.Citation53 For those with severe COPD, a higher BMI was a predictor for GERD (OR 1.2 [95% CI 1.0–1.6]).Citation56 While the BMI of participants in these studies did not meet the criteria for obesity (>30 kg/m2), a greater BMI impacts on the contour of the diaphragm and will influence the elastic work of breathing.Citation21 When combined with respiratory-related risk factors, this may increase the contribution of a higher BMI to GERD in COPD. The prediction of a higher BMI being a contributing factor is not unexpected, given that it is identified as a common contributing factor in the general population.Citation102

Other comorbidities, including cardiac disease and obstructive sleep apnea, have also been associated with a heightened risk of GERD.Citation53 In those with obstructive sleep apnea, increased intrathoracic pressure during apneic episodes is accompanied by increased transdiaphragmatic pressure, which encourages migration of gastric contents up the esophagus.Citation103 The repetitive pressure changes also contribute to LES insufficiency.Citation103 Whether they are independent variables or common consequences of poor diet and obesity remains to be established.Citation104

Influence of GERD on COPD severity

Two of the possible mechanisms by which GERD may impact on the severity of COPD are vagally mediated reflex bronchoconstriction and pulmonary microaspiration.Citation105 Vagally mediated reflex bronchoconstriction originates from the shared autonomic innervation between the tracheobronchial tree and the esophagus. The presence of esophageal acid in the distal esophagus stimulates airway irritation and an inflammatory response, with the release of potent mediators of bronchoconstriction.Citation106 The second mechanism by which GERD may impact on respiratory disease is pulmonary microaspiration. During microaspiration, refluxed gastric material extends proximally to the esophagus and then enters the hypopharynx, directly triggering a laryngeal or tracheal response, which may manifest as coughing, wheezing, or a sensation of dyspnea.Citation105

The relationship between the severity of COPD based on measures of lung function and GERD is controversial, with studies demonstrating mixed results. Some studies observed no significant relationship between GERD and pulmonary function, based on dynamic and static lung volume measurements or pulmonary resistance,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation49,Citation56,Citation57,Citation96,Citation107 whereas other studies found poorer lung function in those with GERD symptoms who had more severe lung disease.Citation12,Citation55 The correlation between oxygen desaturation and nocturnal episodes of distal reflux suggests that GERD may influence nocturnal respiratory status in some patients.Citation11 A single dimension of disease severity may be insufficient to accurately reflect the relationship between GERD and COPD, which may require serial measures of lung function over time.

Interaction between GERD and acute exacerbations of COPD

A large proportion of health care expenditure is related to hospital costs for those admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD),Citation3,Citation108 and prompt intervention is critical in preventing hospital admissions.Citation4 A systematic review and meta-analyses of seven observational studies over varying durations of follow-up (12–18 months) found the presence of GERD to be associated with a greater risk of experiencing an AECOPD (risk ratio 7.57 [95% CI 3.84–14.94]).Citation109 More recent studies outlined in have consistently demonstrated this positive relationship and have noted a higher rate of hospitalization or emergency room visitsCitation52,Citation54,Citation55,Citation57,Citation59,Citation60,Citation79,Citation83,Citation110–Citation113 among the GERD population. This is consistent with a defined phenotype for patients with COPD who experience frequent AECOPD (two per year), with GERD as an independent predictor.Citation113 Studies with a 5-year follow-up found that those who experience both nocturnal and daytime symptoms experienced more exacerbations, with a higher risk in those who did not use regular acid inhibitory treatment (HR 2.7 [95% CI 1.3–5.4]).Citation113

Table 2 Studies exploring the effect of GERD on AECOPD

Establishing the precise nature of the relationship between AECOPD and GERD is challenging. Individuals with COPD often demonstrate lower airway bacterial colonization, which may increase their susceptibility to inflammation and infection.Citation114 GERD may increase this bacterial load in the lower airways and thereby increase the risk of exacerbations.Citation83 With increased pneumonia and wheezing in those with GERD symptoms,Citation53 it might be that recurrent aspiration contributes to pneumonia. If GERD is an independent predictor of AECOPD (independent of respiratory infection, degree of airway obstruction, heart failure, cardiac medications, poor adherence to medical therapy, and older age),Citation54,Citation109,Citation112 then it may represent a modifiable risk factor.

Impact on quality of life

Comorbidities in COPD may exert influence on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). When GERD was defined by esophageal pH monitoring, it had only a minimal impact on disease-specific HRQOL among those with moderate to severe COPD,Citation11,Citation115 an observation confirmed using GERD-specific questionnaires.Citation115 However, some studies with a greater sample size have reported a poorer HRQOL reflected in disease-specific and generic questionnairesCitation53,Citation57 as well as greater levels of anxiety and depression.Citation96 In those aged over 65 years, GERD was associated with a poorer perception of physical health and higher rates of depression and anxiety.Citation116

Cost consequences of GERD in COPD

A substantial proportion of the economic burden associated with COPD is from hospitalization secondary to an acute exacerbation.Citation108,Citation117 According to a retrospective cost study of 2,461 individuals aged >65 years,Citation116 in the 29% who had coexisting COPD and GERD, the annual Medicare cost was $US36,793 per patient per year compared to US$24,722 for those without GERD.Citation116 This 36% increase in costs was attributed to hospitalization for AECOPD. Although specific direct and indirect costs are not yet available, the economic burden appears to be heightened for those with COPD in whom GERD is a comorbidity.

Treatment of GERD

Lifestyle modification and medical and surgical management have all been used to treat GERD. Suggestions for minimizing the risk of GERD include weight loss, avoidance of late-night meals, and specific food and drink that might aggravate reflux by relaxing the LES.Citation21 Altered posture, including adapting a semirecumbent posture when sleeping and avoiding sleeping on the left sideCitation21 have also been suggested.Citation38 Stress reduction has also been associated with symptom improvement.Citation21 These broad recommendations also apply to individuals without COPDCitation38 and are generally recommended as first-line management.

Pharmacologic management includes antacids, histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2-RA), and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy,Citation21 as determined by the severity of GERD. There have been few studies of antireflux therapy specifically for those with COPD (). In a 12-month trial of 100 older patients with GERD, PPI therapy reduced the frequency of AECOPD and common colds compared to usual care.Citation118 Improvement in symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux, GERD, and respiratory symptoms in individuals with COPD has been found with a combined approach of H2-RA and PPI therapy in some studies.Citation12,Citation79 Although several studies reported on the prescription of antireflux medication in COPD, they did not report on the impact of therapy on lung function.Citation12,Citation56,Citation57 Therefore, the effects of pharmacological management of GERD on lung function, the co-occurrence of respiratory and GERD symptoms, and the use of respiratory medications remain to be clarified. The persistence of symptoms despite antireflux therapy suggests that acid reflux may not always be the primary cause;Citation119 this pharmacological approach does not target nonacid or weakly acidic reflux. Surgical management, with a Nissen Fundoplication, has been successfully applied to patients with severe lung disease, including COPD, awaiting transplantation,Citation120–Citation122 with reductions in symptoms of GERD as well as of lung diseaseCitation123 and improved lung function in the small group of individuals with COPD.Citation120–Citation122 Antireflux surgery is not widely used in COPD but should be considered when medical management fails, especially when GERD remains severe in individuals with COPD at risk of respiratory deterioration.

Table 3 Effects of medical and surgical treatment on GERD in COPD

Conclusion

GERD is a common comorbidity in those with COPD and has a variety of clinical presentations. The index of clinical suspicion should remain high, and objective measures should be used for diagnostic confirmation. The best way to identify pulmonary microaspiration of gastric contents in COPD remains to be established. The presence of GERD appears to increase the risk of an AECOPD and may affect disease progression. Although the co-occurrence of these two common conditions may be associated with increased health care utilization, treatment approaches that have been successfully applied in individuals with GERD without COPD also appear to be effective in the presence of COPD.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease [homepage on the Internet]Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2014 Available from: http://www.goldcopdAccessed 24 February, 2015

- SeemungalTDonaldsonGPaulEBestallJJeffriesDWedzichaJEffect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med1998157141814229603117

- VosTFlaxmanANaghaviMYears lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet20123802163219623245607

- SeemungalTDonaldsonGBhowmikAJeffriesDJWedzichaJATime course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001611608161310806163

- RycroftCHeyesALanzaLBeckerKEpidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a literature reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012745749422927753

- VakilNVan ZantenSKahrilasPJDentJJonesRThe Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensusAm J Gastroenterol20061011900192016928254

- El-SeragHSweetSWinchesterCDentJUpdate on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal disease: a systematic reviewGut201463687188023853213

- SifrimDHollowayRSilnyJAcid, nonacid, and gas reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease during ambulatory 24-hour pH-impedance recordingsGastroenterology200112071588159811375941

- DucolonéAVandevenneAJouinHGastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthma and chronic bronchitisAm Rev Respir Dis19871353273323813193

- SweetMPattiMHoopesCHayesSRGoldenJAGastro-oesophageal reflux and aspiration in patients with advanced lung diseaseThorax20096416717319176842

- CasanovaCBaudetJSdel Valle VelascoMIncreased gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with severe COPDEur Respir J20042384184515218995

- MokhlesiBMorrisAHuangC-FCurcioABarrettTKampDIncreased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in patients with COPDChest200111941043104811296167

- MittalRHollowayRPenaginiRBlackshawLDentJTransient lower esophageal sphincter relaxationGastroenterology19951096016107615211

- SchoemanMNTippettMDAkkermansLMDentJHollowayRHMechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in ambulant healthy human subjectsGastroenterology1995108183917806066

- MittalRMcCallumRCharacteristics and frequency of transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with reflux esophagitisGastroenterology1988955935993396810

- DentJHollowayRToouliJDoddsWMechanisms of lower oesophageal sphincter incompetence in patients with symptomatic gastro-oesophageal refluxGut198829102010283410327

- ChandrasomaPDeMeesterTRGERD: Reflux to Esophageal AdenocarcinomaSan DiegoElsevier2006

- VandenplasYHassallEMechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200235211913612187285

- RichterJGastroesophageal reflux diseaseYamadaTTextbook of GastroenterologyPhiladelphiaLippincott Williams and Williams200311961224

- KahrilasPDoddsWJHoganWEffect of peristaltic dysfunction on esophageal volume clearanceGastroenterology19889473803335301

- KatzPOGersonLBVelaMFCorrigendum: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseAm J Gastroenterol201310830832823419381

- KlauserASchindlbeckNMuller-LissnerSSymptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux diseaseLancet19903352052081967675

- LockeGITalleyNFettSPrevalence and clinical spectrum of gas-troesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, MinnesotaGastroenterology1997112144814569136821

- FlookNJonesRVakilNApproach to gastroesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Putting the Montreal definition into practiceCan Fam Physician20085470170518474703

- StanghelliniVArmstrongDMonnikesHBardhansKSystematic review: do we need a new gastro-oesophageal reflux disease questionnaire?Aliment Pharmacol Ther20041946348914987316

- FraserADelaneyBMoayyediPSymptom-based outcome measures for dyspepsia and GERD trials: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol200510044245215667506

- Juul-HansenPRydningAJackobsenCHansenTHigh dose proton-pump inhibitors as a diagnostic test of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in endoscopic-negative patientsScand J Gastroenterol20013680681011495074

- FassROfmanJGastroesophageal reflux disease – should we adopt a new conceptual framework?Am J Gastroenterol20029781901190912190152

- RichterJSevere reflux esophagitisGastroenterol Clin North Am19944677

- DeMeesterTRWangCIWernlyJATechniques, indications and clinical use of 24 hour oesophageal monitoringJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg1980796566707366233

- JamiesonJRSteinHJDeMeesterTRAmbulatory 24-pH esophageal pH monitoring: normal values, optimal thresholds, specificity, sensitivity and reproducibilityAm J Gastroenterol1992879110211111519566

- StreetsCDeMeesterTAmbulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring: why, when and what to doJ Clin Gastroenterol2003371142212811203

- JohnssonFJoelssonBIsbergP-EAmbulatory 24 hour intraesophageal pH-monitoring in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseGut198728114511503315881

- DobhanRCastellDNormal and abnormal proximal esophageal acid exposure: results of ambulatory dual-probe pH monitoringAm J Gastroenterol199388125298420269

- JohnsonLDeMeesterTTwenty-four pH monitoring of the distal esophagus: a quantitative measure of gastroesophageal refluxAm J Gastroenterol1974623253324432845

- VaeziMSchroederPRichterJReproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoringAm J Gastroenterol1997928258299149194

- EmerenzianiSRibolsiMPasqualettiPCicalaMProximal reflux sensitivity: measurement of acid exposure of proximal esophagus: a better tool for diagnosing non-erosive reflux diseaseNeurogastroenterol Motil201123711e324

- KatzPOMatheusTTelemetry capsule for ambulatory pH monitoring: is it time for a change?Am J Gastroenterol20081032986298718786108

- ShaySBomeliSRichterJMultichannel intraluminal impedance accurately detects fasting, recumbent reflux events and their clearingAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol2002283376383

- SifrimDSilnyJHollowayRJanssensJPatterns of gas and liquid reflux during transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. A study using intraluminal electrical impedanceGut19994447549862825

- D’OvidioFSingerLGHadjiliadisDPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in end-stage lung disease candidates for lung transplantAnn Thorac Surg2005801254126116181849

- SweetMPHerbellaFALeardLThe prevalence of distal and proximal gastroesophageal reflux in patients awaiting lung transplantationAnn Surg2006244449149716998357

- SoleMLConradJBennettMPepsin and amylase in oral and tracheal secretions. A pilot studyAm J Crit Care201423433433824986175

- PotluriSFriedenbergFParkmanHPComparison of a salivary/sputum pepsin assay with 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring for detection of gastric reflux into the proximal esophagus, oropharynx and lungDig Dis Sci20034891813181714561007

- WardCForrestIABrownleeIAPepsin like activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is suggestive of gastric aspiration in lung allograftsThorax20056087287416055614

- StovoldRForrestIACorrisPAPepsin, a biomarker of gastric aspiration in lung allografts. A putative association with rejectionAm J Respir Crit Care Med20071751298130317413126

- BlondeauKMertensVVanaudenaerdeBAGastro-oesophageal reflux and gastric aspiration in lung transplant patients with or without chronic rejectionEur Respir J20083170771318057058

- RederNDavisCKovacsEFisichellaPThe diagnostic value of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms and detection of pepsin and bile acids in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and exhaled breath condensate for identifying lung transplantation patients with GERD-induced aspirationSurg Endosc20142861794180024414458

- LeeALButtonBDenehyLProximal and distal gastro-oesophageal reflux in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasisRespirology201419221121724033416

- TimmsCThomasPYatesDDetection of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in patients with obstructive lung disease using exhaled breath profilingJ Breath Res2012601600322233591

- KostikasKPapatheodorouGGanasKPsathakisKPanagouPLoukidesSpH in expired breath condensate of patients with inflammatory airway diseasesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002165101364137012016097

- TeradaKMuroSSatoSImpact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationThorax20086395195518535116

- MartinezCHOkajimaYMurraySCOPDGene InvestigatorsImpact of self-reported gastroesophageal reflux disease in subjects from COPD Gene cohortRespir Res2014156224894541

- LiangB-MFengY-LAssociation of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLung201219027728222258420

- RoghaMBehraveshBPourmoghaddasZAssociation of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gastrointest Liver Dis2010193253256

- KempainenRSavikKWhelanTDunitzJHerringtonCBillingsJHigh prevalence of proximal and distal gastroesophageal reflux disease in advanced COPDChest20071311666167117400682

- Rascon-AguilarIEPamerMWludykaPRole of gastroe-sophageal reflux symptoms in exacerbations of COPDChest20061301096110117035443

- BorSKitapciogluGSolakZErtilavMErdincMPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20102530931319817951

- ShimizuYDobashiKKusanoMMoriMDifferent gastroesophageal reflux symptoms of middle-aged to elderly asthma and chronic objective pulmonary disease patientsJ Clin Biochem Nutr201150216917522448100

- TakadaKMatsumotoSKojimaEProspective evaluation of the relationship between acute exacerbations of COPD and gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnosed by questionnaireRespir Med20111051531153621454063

- PhulpotoMOzyyumSRizviNKhuhawareSProportion of gastroesophageal symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Pak Med Assoc20055527627916108509

- KambleNKhanNKumarNNayakHDagaMStudy of gastrooesophageal reflux disease in patients with mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in IndiaRespirology20131846346723062059

- AndersenLJensenGPrevalence of benign oesophageal disease in the Danish population with special reference to pulmonary diseaseJ Intern Med19892253934012787376

- GadelAAMostafaMYounisAHaleemMEsophageal motility pattern and gastroesophageal reflux in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHepatogastroenterology2012591202498250223178615

- WeustenBAkkermansLvanBerge-HenegouwenGPSmoutAJSpatiotemporal characteristics of physiological gastroesophageal refluxAm J Physiol1994266G357G3628166276

- DeMeesterTJohnsonLJosephGToscanoMHallASkinnerDPatterns of gastroesophageal reflux in health and diseaseAnn Surg1976184445947013747

- DentJEl-SeragHWallanderMJohanssonSEpidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic reviewGut20055471071715831922

- AreiasVCarreiraSAnciaesMPintoPBarbaraCCo-morbidities in patients with gold stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRev Port Pneumol201420151123993405

- McCollEBest practice in symptom assessment: a reviewGut200453suppl 44954

- El-SeragHSonnenbergAComorbid occurrence of laryngeal or pulmonary disease with esophagitis in United States Military VeteransGastroenterology19971137557609287965

- Garcia RodriguezLRuigomezAMartin-merinoEJohanssonSWallanderMRelationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and COPD in UK primary careChest200813461223123018689591

- PandolfinoJEKahrilasPJSmoking and gastro-esophageal reflux diseaseEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol20001283784210958210

- KadakiaSCKikendallJWMaydonovitchCJohnsonLFEffect of cigarette smoking on gastroesophageal reflux measured by 24-h ambulatory esophageal pH monitoringAm J Gastroenterol199590178517907572895

- KimSLeeJSimYRyuYChangJPrevalence and risk factors for reflux esophagitis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseKorean J Intern Med20142946647325045294

- HillCJonesRSystematic review: the epidemiology of gastrooesophageal reflux disease in primary care, using the UK general practice research databaseAliment Pharmacol Ther20092947048019035977

- RahmanIOxidative stress in pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cellular and molecular mechanismsCell Biochem Biophys20054316718816043892

- FarrellSMcMasterCGibsonDShieldsMMcCallionWPepsin in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: a specific and sensitive method of diagnosing gastrooesophageal reflux-related pulmonary aspirationJ Pediatr Surg20064128929316481237

- PauwelsADecraeneABlondeauKBile acids in sputum and increased airway inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosisChest201214161568157422135379

- EryukselEDoganMOlgunSKocakICelikelTIncidence and treatment results of laryngopharyngeal reflux in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Arch Otorhinolaryngol200926681267127119221778

- LeeAButtonBDenehyLExhaled breath condensate pepsin: potential noninvasive test for gastroesophageal reflux in COPD and bronchiectasisRespir Care201560224425025352687

- OrrWElsenbruchSHarnishMJohnsonLProximal migration of esophageal acid perfusions during waking and sleepAm J Gastroenterol200095374210638556

- FortunatoGMachadoMAndradeCFelicettiJCamargoJCardosoPPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in lung transplant candidates with advanced lung diseaseJ Bras Pneumol2008341077277819009209

- TeradaKMuroSOharaTAbnormal swallowing reflex and COPD exacerbationsChest2010137232633219783670

- TeramotoSKumeHOuchiYAltered swallowing physiology and aspiration in COPDChest200212231104110512226067

- GrossRAtwoodDJRossSOlszewskiJEichhornKThe coordination between breathing and swallowing in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179755956519151193

- MokhlesiBLogemannJARademakerAWStanglCACorbridgeTCOropharyngeal deglutition in stable COPDChest2002121236136911834644

- MokhlesiBClinical implications of gastroesophageal reflux disease and swallowing dysfunction in COPDAm J Respir Med20032211712114720011

- PauwelsABlondeauKDupontLSifrimDMechanisms of increased gastroesophageal reflux in patients with cystic fibrosisAm J Gastroenterol201210791346135322777342

- TurbyvilleJApplying principles of physics to the airway to help explain the relationship between asthma and gastroesophageal refluxMed Hypotheses2010741075108020080360

- FieldSUnderwoodMBrantRCowieRPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in asthmaChest19961093163228620699

- NaliboffBDMayerMFassRThe effect of life stress on symptoms of heartburnPsychosom Med200466342643415184707

- SteinMTownerTWeberRThe effect of theophylline on the lower esophageal sphincter pressureAnn Allergy1980452387425397

- CrowellMZayatELacyBThe effects of an inhaled B2-adrenergic agonist on lower esophageal function: a dose-response studyChest200112110241027

- KimJLeeJHKimYAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national cross-sectional cohort studyBMC Pulmon Med20131351

- RuzkowskiCSanowskiRAustinJRohwedderJJWaringJPThe effects of inhaled albuterol and oral theophylline on gastroesophageal reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive lung diseaseArch Intern Med199215247837851558436

- NiklassonAStridHSimrenMEngstromC-PBjornssonEPrevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200820433534118334878

- SontagSO’ConnellSKhandelwalSMillerTNemchauskyBSchnellTMost asthmatics have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapyGastroenterology1990996136202379769

- HubertDGaudricMGuerreJLockhartAMarsacJEffect of theophylline on gastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol198881116811742897987

- KuligMNoconMViethMRisk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease: methodology and first epidemiological results of the ProGERD studyJ Clin Epidemiol20045758058915246126

- LockeRTalleyNFettSZinsmeisterAMeltonJRisk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal refluxAm J Med199910664264910378622

- DoreMMaragkoudakisEFraleyKDiet, lifestyle and gender in gastroesophageal reflux diseaseDig Dis Sci200853820172032

- CorleyDKuboABody mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol20061082619262816952280

- DemeterPPapAThe relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive sleep apneaJ Gastroenterol20043981582015565398

- ZagariRMFuccioLWallanderMAGastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus in the general population: the Loiano-Monghidoro studyGut200857101354135918424568

- HardingSGERD, airway disease and the mechanisms of interactionSteinMGastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Airway DiseaseNew YorkMarcel Dekker Inc1999162163

- CanningBMazzoneSReflex mechanisms in gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthmaAm J Med200311545S48S12928074

- OrrWShamma-OthmanZAllenMRobinsonMEsophageal function and gastroesophageal reflux during sleep and waking in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChest1992101152115251600768

- GuarascioARaySFinchCSelfTThe clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USAClinicoeconom Outcomes Res20135235245

- SakaeTPizzichiniMTeixeiraPde SilvaRTrevisolDPizzichiniEExacerbations of COPD and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Bras Pneumol201339325927123857694

- OzyilmazEKokturkNTeksutGTatliciogluTUnsuspected risk factors of frequent exacerbations requiring hospital admission in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInter J Clin Pract201367691697

- LinYTsaiCChienLChiouHJengCNewly diagnosed gastroesophageal reflux disease increased the risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during the first year following diagnosis – a nationwide population-based cohort studyInter J Clin Pract2015693350357

- HurstJVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- IngebrigtsenTMarottJVestboJNordestgaardBHallasJLangePGastroesophageal reflux disease and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology20152010110725297724

- Pacheco-GalvanAHartSMoriceARelationship between gastrooesophageal reflux and airway diseases: the airway reflux paradigmArch Bronchoneumol201147195203

- LeeALGastro-oesophageal reflux in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasisPhD ThesisMelbourneThe University of Melbourne2009

- AjmeraMRavalAShenCSambamoorthiUExplaining the increased health care expenditures associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cost-decomposition analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014933934824748785

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care2010 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101/chapter/1-guidanceAccessed 24 February, 2015

- SasakiTNakayamaKYasudaHA randomised, single-blind study of lansoprazole for the prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc20095781453145719515110

- StorrMAWhat is nonacid reflux disease?Can J Gastroenterol2011251353821258666

- HartwigMGAndersonDJOnaitisMWFundoplication after lung transplantation prevents the allograft dysfunction associated with refluxAnn Thorac Surg201192246246821801907

- GasperWJSweetMPHoopesCAntireflux surgery for patients with end-stage lung disease before and after lung transplantationSurg Endosc20082249550017704875

- HoppoTJaridoVPennathurAAntireflux surgery preserves lung function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and end-stage lung disease before and after lung transplantationArch Surg201114691041104721931001

- EkstromTJohanssonKEffects of anti-reflux surgery on chronic cough and asthma in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux diseaseRespir Med200094121166117011192951