Abstract

Background

Assessment of dyspnea in COPD patients relies in clinical practice on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, whereas the Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) is mainly used in clinical trials. Little is known on the correspondence between the two methods.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis was carried out on data from the French COPD cohort Initiatives BPCO. Dyspnea was assessed by the mMRC scale and the BDI. Spirometry, plethysmography, Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, exacerbation rates, and physician-diagnosed comorbidities were obtained. Correlations between mMRC and BDI scores were assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. An ordinal response model was used to examine the contribution of clinical data and lung function parameters to mMRC and BDI scores.

Results

Data are given as median (interquartile ranges, [IQR]). Two-hundred thirty-nine COPD subjects were analyzed (men 78%, age 65.0 years [57.0; 73.0], forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] 48% predicted [34; 67]). The mMRC grade and BDI score were, respectively, 1 [1–3] and 6 [4–8]. Both BDI and mMRC scores were significantly correlated at the group level (rho =−0.67; P<0.0001), but analysis of individual data revealed a large scatter of BDI scores for any given mMRC grade. In multivariate analysis, both mMRC grade and BDI score were independently associated with lower FEV1% pred, higher exacerbation rate, obesity, depression, heart failure, and hyperinflation, as assessed by the inspiratory capacity/total lung capacity ratio. The mMRC dyspnea grade was also associated with the thromboembolic history and low body mass index.

Conclusion

Dyspnea is a complex symptom with multiple determinants in COPD patients. Although related to similar factors (including hyperinflation, depression, and heart failure), BDI and mMRC scores likely explore differently the dyspnea intensity in COPD patients and are clearly not interchangeable.

Background

COPD is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide.Citation1 It is characterized by progressive airflow limitation; COPD severity was until recently mainly defined by the level of post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).Citation2 Dyspnea is the predominant symptom of COPD, both in stable condition and during exacerbations, and appears now as a major index of disease severity and a prominent target of treatment. Dyspnea has been shown to be weakly associated with the most common lung function parameters, particularly with FEV1,Citation3,Citation4 suggesting the contribution of many other factors. Comorbidities, defined as specific chronic diseases distinct, and associated with COPD, are frequent in COPD and their importance is being increasingly recognized.Citation5 They impact many aspects of the disease, and interfere with its natural history. For example, high rates of cardiovascular diseases (eg, chronic heart failure) and mood disorders (eg, anxiety and depression) have been reported in COPD patientsCitation5,Citation6 and suggested as contributing to dyspnea.Citation7,Citation8

In daily practice, dyspnea level is usually measured by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale. This scale is easy to use and has a prognostic value, and was thus included in all simplified prognostic scores such as the Body mass index–airflow Obstruction–Dyspnea, and Exercise (BODE) index.Citation9 Moreover, evaluation of the level of dyspnea by the mMRC is now used to categorize COPD symptomatic burden in the new Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommendations and provides useful information about COPD-induced disability.Citation2,Citation10,Citation11 However, its unidimensional structure and limited number of degrees are well-recognized limitations. Furthermore, a major disadvantage of mMRC is that it shows little change with therapeutic interventions. This led investigators to develop other tools for evaluating the impact of therapies on dyspnea levels. Among these tools, the Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) has been designed for a multidimensional assessment of dyspnea, and the corresponding Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) appears to be much more sensitive to changes than the mMRC.Citation3 The BDI/TDI has been widely validated in COPD and remains the most frequently used questionnaire in clinical research, particularly for therapeutic trials.Citation12–Citation14 The correlations between mMRC and BDI scores for dyspnea assessment have been reported in two studies by Mahler et alCitation12,Citation15 with correlation coefficients between 0.61 and 0.73. However, no details were given on individual concordance or discrepancies between these two measurements.

In the present study, the mMRC and BDI scores were used to evaluate dyspnea in COPD patients recruited in the INITIATIVES BPCO cohort.Citation16 Our goals were 1) to analyze the relationships between mMRC scale and BDI score and 2) to evaluate the independent contributions of nutritional status, exacerbation rate, comorbidities (including anxiety-depression), spirometry, and lung volumes to dyspnea levels, as assessed by mMRC vs BDI.

Methods

The INITIATIVES BPCO cohort

COPD subjects included in the present analysis were recruited in the INITIATIVES BPCO cohort between January 2005 and August 2009. The INITIATIVES BPCO cohort is a real-world cohort of clinically and spirometry-diagnosed COPD patients identified in 17 pulmonary units of university hospitals located throughout France. Data are recorded in a standardized case report form but, due to the real-world nature of patient care, datasets do not have to be complete to include a patient. Only demographic characteristics and spirometry are mandatory. Detailed information about this cohort can be found in a previous report.Citation16 Respiratory physicians prospectively recruited subjects in stable condition (no history of exacerbation requiring medical treatment for the previous 4 weeks) with a diagnosis of COPD based on a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity) ratio <70%.Citation17 Subjects with a main diagnosis of bronchiectasis, asthma, or any other significant respiratory diseases were carefully excluded. At the time of the analyses, the INITIATIVES BPCO cohort contained data on 633 COPD subjects. Because our goal was to study the impact of both lung function and comorbidities on dyspnea scores, we selected subjects with complete data for spirometry, plethysmography, comorbidities (coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, thromboembolic history, diabetes, hypertension), Hospital Anxiety–Depression (HAD) Scale, Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and numbers of acute exacerbations of COPD during the previous year. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Versailles (France), and all subjects provided informed written consent.

Data collection

We used a standardized characterization process that covered demographic data, risk factors including cumulative tobacco smoking, and COPD characteristics (including symptoms and spirometry) in stable condition. Pulmonary function tests were performed according to international standards,Citation18 and included a spirometry and an optional plethysmographic assessment of lung volumes. Severity of airflow obstruction was evaluated according to GOLD classification.Citation17 The number of acute exacerbations of COPD during the previous year was determined according to patient’s self-report. Comorbidities (including congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus) were identified from the patient files (physician-diagnosed comorbidities). Malnutrition was defined by body mass index (BMI) ≤18.5 kg/m2 and obesity by a BMI >30 kg/m2.Citation19 Dyspnea was assessed by the mMRC scaleCitation11 ranging from 0 to 4 and by the French version of the BDI, previously validated in COPD.Citation20 Total BDI score (0–12, 12 meaning no dyspnea) and individual dimensions (functional impairment, magnitude of task, and magnitude of effort, all three ranging from 0 to 4) were analyzed. The HAD scale was used to evaluate mood disorders. This 14-item self-questionnaire has two seven-item subscales for anxiety (HAD-A) and depression (HAD-D). Scores range from 0 to 21 for each subscale, and a score of 10 or higher on either subscale is closely associated with the presence of the corresponding mood disorder.Citation21 HRQoL was evaluated using the original SGRQ.Citation22

Statistical analysis

The normality of mMRC and BDI distribution was evaluated by a Shapiro–Wilk test (W).

Univariate analysis

With qualitative variables, the values of mMRC and BDI are presented using median and IQR for each level of the variables, and Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used.

With quantitative variables, the relations between mMRC and BDI scores are presented using Spearman correlation coefficients.

Variables of interest were age, symptoms of chronic bronchitis, FEV1, lung volumes, exacerbation frequency, HAD-anxiety and -depression subscores, nutritional status, and comorbidities including diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease), venous thromboembolism, and diabetes.

Multivariate analysis

Stepwise ordinal logistic regressions were performed in order to find parameters that explain mMRC and BDI scores, using the LOGISTIC procedure from SAS® 9.2 statistical software, with a significant level of entry of 15% and a significant level of stay of 10% as criteria for introducing or removing a covariate. For each score, two stepwise regressions were performed:

– Starting from no variable.

– Starting from all variables.

Each time, the two stepwise regressions converged to the same model.

Twelve variables were used as covariates.

Lung function variables were included as continuous (FEV1% pred, FVC% pred, functional residual capacity [FRC]% pred) or categorical (inspiratory capacity/total lung capacity ratio [IC/TLC], ≥25% or <25%) variables. Comorbidities were included as individual variables. HAD-A and HAD-D were entered as no or significant anxiety/depression, corresponding to values ≥10 for each subscore. BMI was entered as a categorical variable (low <18.5 kg/m2; obesity >30 kg/m2). Our univariate analysis showed a close relationship between dyspnea and HRQoL. We therefore deliberately excluded SGRQ from our multivariate analysis, to unmask other contributing factors.

Results

Patients

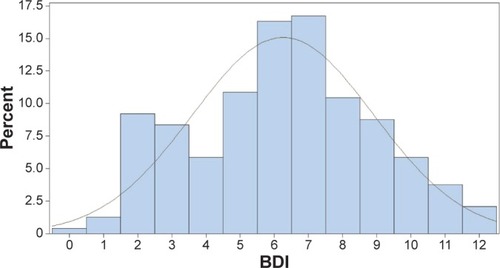

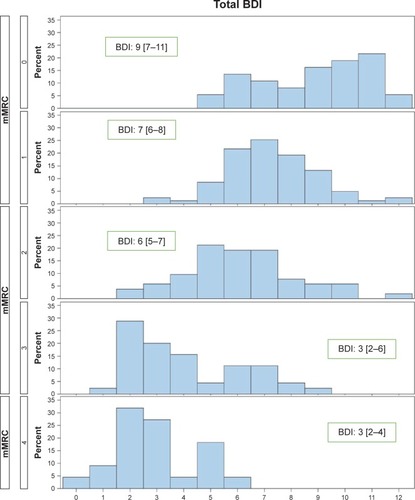

The present analysis included 239 subjects (53 women, 186 men) with a mean tobacco consumption of 42.6 [25; 56] pack-years. A comparison of the 239 patients with complete data to the remaining subjects with incomplete data was performed. Subjects with complete data had a tendency toward higher FVC (2.82 L vs 2.71 L; P=0.08), a higher rate of symptoms of chronic bronchitis (81% vs 67%, P=0.0003). No other differences were found between included and excluded subjects for clinical and lung function variables. All GOLD spirometry grades were represented (). Previously diagnosed comorbidities were found across all GOLD grades. The mean SGRQ total score was 45.3 [31.9; 60.9]. Mean FEV1 was 48% pred [34; 67]. Median mMRC and BDI scores were, respectively, 1 [1; 3] and 6 [4; 8]. The distributions () of BDI and mMRC scores were non-Gaussian: for mMRC: W=0.899, P<0.0001; for BDI: W=0.973, P=0.0002. The mMRC grades and BDI scores correlated (rho =−0.672; P<0.0001) at the group level, but large variations of BDI values were observed for a given mMRC grade (). Although correlations were also found between mMRC and individual BDI dimensions (functional impairment: rho =−0.621, P<0.0001; magnitude of task: rho =−0.589, P<0.0001; magnitude of effort: rho =−0.581, P<0.0001), the dispersion of BDI subscores for each level of mMRC was as wide as for the total score (data not shown).

Table 1 Description of patients characteristics by GOLD grade of airflow obstruction

Univariate determinants of mMRC and BDI scores

Several categorical variables were related to mMRC and BDI scores, particularly a low BMI, depression, and severe hyperinflation (IC/TLC <25%) (). In addition, the mMRC and BDI scores were both highly correlated with SGRQ total score (). The correlation levels with lung function variables appeared similar for mMRC and BDI scores. BDI score and subscores were more closely correlated with clinical variables (SGRQ and HAD scores) than with lung function variables. Among them, the higher correlations were observed with FEV1, followed by the level of hyperinflation as assessed by IC/TLC and FRC/TLC. The relationships between mMRC and BDI scores with FRC% pred and RV% pred were significantly lower.

Table 2 Univariate analysis of categorical variables associated with mMRC/BDI

Table 3 Univariate analysis of mMRC/BDI correlates, using numerical variables

For all variables but BMI, the Spearman correlation coefficients were higher with BDI functional impairment, lower with BDI magnitude of effort, and intermediate with BDI magnitude of task.

Multivariate determinants of mMRC and BDI scores

Our univariate analysis showed a close relationship between dyspnea and HRQoL, according to previous studies.Citation11,Citation23 We, therefore, deliberately excluded SGRQ from our multivariate analysis, to unmask other contributing factors.

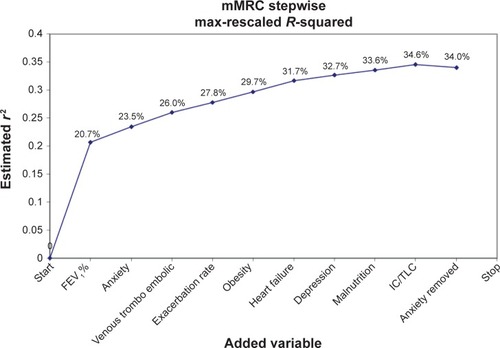

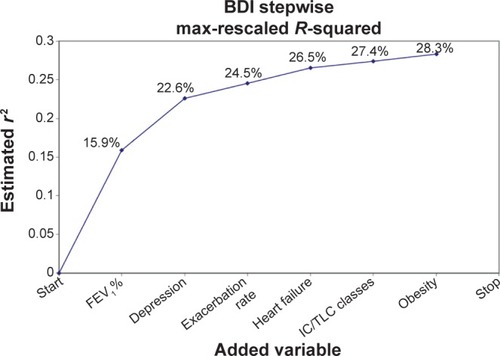

The results of ordinal logistic regression for mMRC grade and BDI score are shown in and ; and . Major determinants (as indicated by high correlation coefficient values) were different for mMRC and BDI scores. For both scores, the first covariate was FEV1. Other independent determinants of both mMRC scale and BDI were exacerbation rate, obesity, heart failure, depression, and IC/TLC. Thromboembolic history and denutrition were significantly associated with the mMRC scale only.

Table 4 Determinants of the mMRC scale in stepwise multivariate analysis

Table 5 Determinants of the BDI total score in stepwise multivariate analysis

Figure 3 Determinants of the mMRC grade (stepwise logistic regression).

Abbreviations: BDI, Baseline Dyspnea Index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; IC, inspiratory capacity; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; TLC, total lung capacity.

Figure 4 Determinants of the BDI score (stepwise logistic regression).

Altogether, combining all independent determinants of dyspnea allowed us to explain only a moderate proportion of mMRC and BDI variations.

Discussion

In this cohort of COPD patients with a wide range of airflow limitation, mMRC dyspnea grades and BDI scores were correlated at the group level. However, for individual patients, large variations of BDI scores were observed for a given level of mMRC. The IQRs of BDI for each mMRC level were between 2 and 4 points, the larger being for mMRC 0 and 3. These two measurements shared most, but not all, of their determinants, which explained a moderate proportion of their variations. These data suggested that mMRC and BDI scores explore quite differently the dyspnea intensity in COPD patients and thus should ideally be used in combination.

mMRC scale vs BDI

The use of appropriate measurement tools and the understanding of the determinants of dyspnea may help the clinician in the management of individual patients. The absence of a gold standard to assess dyspnea has to be underlined. Our results obtained in a large cohort of stable patients with well-defined COPD demonstrate that mMRC scale and BDI may refer to markedly different levels of dyspnea severity on an individual basis. In the two studies by Mahler et al enrolling 101 and 66 patients, the correlation coefficients between mMRC and BDI scores ranged from 0.61 to 0.73, but no further details were provided about the magnitude of discrepancies between these tools. Another study comparing the mMRC, BDI, and oxygen cost diagram concluded that these tools were equivalent in a cross-sectional assessment, as they had the same distribution pattern.Citation24 However, in all these studies, concordance at an individual level was not investigated or at least not reported. The BDI score has the potential advantage of covering several sensory components of dyspnea and might confer a more precise evaluation of dyspnea intensity and impact on daily life than mMRC. The sensitivity of BDI/TDI to longitudinal changes is also much higher.Citation13,Citation25 The reasons for marked dispersion of BDI scores for a given mMRC dyspnea level (particularly for mMRC grades 0 and 3) in our population are difficult to determine.

Clinical and lung function correlates of dyspnea were very similar for both questionnaires, except for thromboembolic history and denutrition. However, the proportion of mMRC variance explained by these two variables was low and these comorbidities were found in only a minority of patients.

Clearly, our results demonstrate that mMRC and BDI scores are not interchangeable for the assessment of dyspnea in an individual patient. mMRC remains a standard tool to evaluate dyspnea in daily practice, and its usefulness is highly emphasized in the new GOLD document. Although the suggested cut-off to define significant symptoms was set at grade 2, recent data suggest that patients with mMRC grade 1 may already exhibit a significant impact of COPD, as assessed by the COPD assessment test (CAT) score.Citation26 However, the vast majority of our patients with grade 1 mMRC had a BDI ≥5 (). The reproducibility of mMRC and BDI scores in stable COPD patients have been found to be satisfactory,Citation15,Citation20 although it might be less for the “classic” BDI than with the self-administered version,Citation12 which is not available in French at present. The discrepancies between BDI and MRC assessments are therefore likely to be reproducible, but the present study was not designed to answer this question.

Determinants of dyspnea

The second main finding of present study is that FEV1, hyperinflation, depression, and comorbidities are all major determinants of mMRC and BDI dyspnea scores. Determinants of dyspnea remain poorly understood in COPD due to the complexity of this symptom and its interindividual variability for the same level of physiologic impairment, for instance, FEV1. The moderate relationship with spirometry has been previously found using both mMRC and BDI scores,Citation3 although overall dyspnea scores deteriorate significantly with GOLD stages.Citation15 Our results confirm these data.Citation27,Citation28

In our patients, hyperinflation was a significant determinant of dyspnea, but the correlation was lower than for FEV1. A few studies have evaluated the relationship between dyspnea and the level of resting hyperinflation. Nishimura et al recently showed a significant relationship with dyspnea, but these authors also found a lower level of correlation than for FEV1.Citation29 A similar level of correlation with dyspnea intensity was found for RV/TLC.Citation24 Our results with IC/TLC confirm these findings.

Although dyspnea is classically more severe in COPD patients with significant anxiety,Citation6,Citation30 conflicting results have been reported recently.Citation31 Notably, factor analysis demonstrated that anxiety was found to be a clearly different factor from dyspnea.Citation24 Although significant in univariate analysis, anxiety was no longer a contributing factor in our multivariate analysis, especially after taking into account the level of depression.

Depression is a frequent comorbidity of COPD, although its prevalence varies widely among studies.Citation8 The relationship between depression and dyspnea has, however, been less investigated than for anxiety. Sanchez et al recently performed a principal component analysis including dyspnea (MRC and BDI), HRQoL, HAD score, and plethysmography data in a large population of 328 patients with altered ventilatory capacity, including 128 COPD patients. Surprisingly, psychological status and dyspnea appeared as separate dimensions.Citation28 The authors hypothesized that BDI and MRC only reflected the sensory dimension of dyspnea, thus neglecting its affective component. Conversely, another study also found that depression was a significant contributor to low HRQoL (SGRQ) in multivariate analysis.Citation23 In our patients, depression appeared much more significantly associated with dyspnea assessed by BDI in multivariate analysis than by mMRC. Treatment of depression in COPD may improve symptoms and HRQoL in COPD patients,Citation32 but randomized studies are clearly lacking to evaluate its impact on dyspnea.

Exacerbation rate is significantly associated with dyspnea in both mMRC and BDI models. The relation between exacerbations and dyspnea is well demonstrated as well as their negative impact on HRQoL.Citation23 Our patients were evaluated in stable condition, but repeated exacerbations may play a role in anticipating forthcoming episodes of increased dyspnea and limitation, leading to what can be called “kinesiophobia” or dyspnea-related fear.Citation31

The relationship with thromboembolic history was rather unexpected since 1) no suspicion of post-embolic pulmonary hypertension was found and 2) the prevalence of chronic post-embolic pulmonary hypertension after a first episode was low.Citation33 However, it must be acknowledged that patients were not systematically assessed for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Heart failure is a frequent comorbidity in COPD patients and plays a role in dyspnea, although it seems difficult to determine its precise contribution in individual patients. Dyspnea is more severe in patients with systolic heart failure and coexisting COPD, and increases with GOLD stages.Citation26 We cannot exclude an underdiagnosis of heart failure (particularly diastolic) in some patients because of the absence of systematic investigations.

Obesity was a contributing factor in both BDI and mMRC models. Conversely, it was recently suggested that moderate obesity could improve dyspnea during exercise in COPD, through its limiting effect on hyperinflation during exercise, but this hypothesis remains controversial.Citation34

Higher degrees of dyspnea are often reported in female COPD patients for a comparable level of FEV1 impairment. Such a finding was recently confirmed in our cohortCitation35 after a careful matching for age and FEV1 level of male vs female patients (3:1 ratio). The difference for mMRC grade was similar in our subset of patients in univariate analysis (mMRC grade 1 in males vs grade 2 in females) but disappeared in the multiple regression. This difference is probably related to the multivariate analysis per se as well as to sampling differences in our cohort between the two studies.

One important strength of the present study is the systematic, simultaneous assessment of comprehensive lung function variables (including lung volumes) and clinical variables. In addition to the simple mMRC scale, we used the BDI score, which remains at present the most sensitive questionnaire to assess the severity of dyspnea and dyspnea-related impact on exercise and activity.

The present study also has some limitations. Our patients were recruited in pulmonary clinics of university hospitals, and therefore may not represent the COPD population at large, with a lower proportion of stage I patients. However, they had a wide range of airflow limitation, indicating various degrees of spirometric severity. The emotional aspects of dyspnea were not assessed due to the MRC and BDI measuring properties. New questionnaires include this dimension and may provide additional information about dyspnea components.Citation36,Citation37 The relationships of these new questionnaires with other COPD components or outcomes remain to be confirmed in large field studies. Another limitation of the present study is that the severity of comorbidities (eg, heart failure) was not precisely assessed. Other potential contributing lung function parameters were unavailable, particularly DLCO, inspiratory muscle strength, expiratory flow limitation, and airway resistance. The latter, either assessed by plethysmography or forced oscillation, was recently shown to correlate significantly with dyspnea in COPD patients.Citation38 Exercise capacity and physical activity were also not evaluated in our study.

However, dyspnea is likely to be a determinant of exercise tolerance and not the contrary, although regular physical activity may play a positive role through its impact on deconditioning.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that, although related on a statistical ground, mMRC and BDI scores may evaluate very differently the dyspnea intensity in individual patients. BDI and mMRC scale thus appear complementary, in the absence of a gold standard tool. New self-administered questionnaires are clearly needed, evaluating both sensory and affective components of dyspnea. These questionnaires should also be highly sensitive to changes, particularly therapeutic interventions. Present results also confirm the complexity of dyspnea determinants in COPD and suggest a significant impact of frequent exacerbations, hyperinflation, and common comorbidities, particularly heart failure and depression.

Author contributions

TP, PRB, and NR contributed to study design, statistical analysis plan, and preparation of manuscript; JLP performed the statistical analysis; DC, GD, and PC contributed to manuscript revision. All authors contributed toward database design, patient recruitment, data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The Initiatives BPCO study group consisted of G Brinchault-Rabin (Rennes), P-R Burgel (Paris), D Caillaud (Clermont-Ferrand), P Carré (Carcassonne), P Chanez (Marseille), A Chaouat (Vandoeuvre les Nancy), I Court-Fortune (Saint-Etienne), A Cuvelier (Rouen), R Escamilla (Toulouse), C Gut-Gobert (Brest), G Jebrak (Paris), F Lemoigne (Nice), P Nesme-Meyer (Lyon), T Perez and the late I Tillie-Leblond (Lille), C Perrin (Cannes), C Pinet (Toulon), C Raherison (Bordeaux), and N Roche (Paris). This work was funded by unrestricted grants from Boehringer Ingelheim France and Pfizer France.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and global analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- GOLDGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2010 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed April 25th, 2015

- MahlerDAWeinbergDHWellsCKFeinsteinARThe measurement of dyspnea. Contents, interobserver agreement, and physiologic correlates of two new clinical indexesChest19848567517586723384

- FerrariKGotiPMisuriGChronic exertional dyspnea and respiratory muscle function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLung199717553113199270988

- FabbriLMLuppiFBegheBRabeKFComplex chronic comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20083120421218166598

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSACCP Workshop Panel on Anxiety and Depression in COPDAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 suppl43S56S18842932

- Le JemtelTHPadelettiMJelicSDiagnostic and therapeutic challenges in patients with coexistent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failureJ Am Coll Cardiol200749217118017222727

- von LeupoldtATaubeKLehmannKFritzscheAMagnussenHThe impact of anxiety and depression on outcomes of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPDChest2011140373073621454397

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2004350101005101214999112

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- MahlerDAWatermanLAWardJMcCuskerCZuWallackRBairdJCValidity and responsiveness of the self-administered computerized versions of the baseline and transition dyspnea indexesChest200713241283129017646223

- JonesPMiravitllesMvan der MolenTKulichKBeyond FEV(1) in COPD: a review of patient-reported outcomes and their measurementInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012769770923093901

- DonohueJFFogartyCLötvallJINHANCE Study InvestigatorsOnce-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol versus tiotropiumAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182215516220463178

- MahlerDAWardJWatermanLAMcCuskerCZuwallackRBairdJCPatient-reported dyspnea in COPD reliability and association with stage of diseaseChest200913661473147919696126

- BurgelPRNesme-MeyerPChanezPInitiatives Broncho-pneumopathie Chronique Obstructive Scientific CommitteeCough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjectsChest2009135497598219017866

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med200717653255517507545

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVATS/ERS Task ForceStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- World Health OrganizationObesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultationWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2000894515

- LaurendeauCPribilCPerezTRocheNSimeoniMCDetournayBValidation study of the BDI/TDI scores in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRev Mal Respir200926773574319953015

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med2007167606717210879

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure for chronic airflow limitation: the St George’s respiratory questionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- BurgelPEscamillaRPerezTImpact of comordities on COPD-specific health-related quality of lifeRespir Med201310723324123098687

- HajiroTNishimuraKTsukinoMIkedaAKoyamaHIzumiTAnalysis of clinical methods used to evaluate dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981584118511899769280

- MahlerDAWardJWatermanLABairdJCDLongitudinal changes in patient-reported dyspnea in patients with COPDCOPD2012952252722876883

- ArnaudisBLairezOEscamillaRImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity on symptoms and prognosis in patients with systolic heart failureClin Res Cardiol2012101971772622484345

- MahlerDARosielloRAHarverALentineTMcGovernJFDaubenspeckJAComparison of clinical dyspnea ratings and psychophysical measurements of respiratory sensation in obstructive airway diseaseAm Rev Respir Dis19871356122912333592398

- SanchezOCaumont-PrimAGillet-JuvinKActivity-related dyspnea is not modified by psychological status in people with COPD, interstitial lung disease or obesityRespir Physiol Neurobiol20121821182522366153

- NishimuraKYasuiMNishimuraTOgaTAirflow limitation or static hyperinflation: which is more closely related to dyspnea with activities of daily living in patients with COPD?Respir Res20111213521988843

- GiardinoNDCurtisJLAndreiACNETT Research GroupAnxiety is associated with diminished exercise performance and quality of life in severe emphysema: a cross-sectional studyRespir Res2010112920214820

- JanssensTDe PeuterSStansLDyspnea perception in COPD: association between anxiety, dyspnea-related fear, and dyspnea in a pulmonary rehabilitation programChest2011140361862521493698

- EiserNHarteRSpirosKPhillipsCIsaacMTEffect of treating depression on quality-of-life and exercise tolerance in severe COPDCOPD20052223324117136950

- BecattiniCAgnelliGPesaventoRIncidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after a first episode of pulmonary embolismChest2006130117217516840398

- OraJLavenezianaPWadellKPrestonMWebbKAO’DonnellDEEffect of obesity on respiratory mechanics during rest and exercise in COPDJ Appl Physiol20111111101921350021

- RocheNDesléeGCaillaudDINITIATIVES BPCO Scientific CommitteeImpact of gender on COPD expression in a real-life cohortRespir Res2014152024533770

- YorkeJMoosaviSHShuldhamCJonesPWQuantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the dyspnoea-12Thorax2010651212619996336

- MeekPMBanzettRParshallMBGracelyRHSchwartzsteinRMLansingRReliability and validity of the multidimensional dyspnea profileChest201214161546155322267681

- MahutBCaumont-PrimAPlantierLRelationships between respiratory and airway resistances and activity-related dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012716517122500118