Abstract

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are defined as sustained worsening of a patient’s condition beyond normal day-to-day variations that is acute in onset, and that may also require a change in medication and/or hospitalization. Exacerbations have a significant and prolonged impact on health status and outcomes, and negative effects on pulmonary function. A significant proportion of exacerbations are unreported and therefore left untreated, leading to a poorer prognosis than those treated. COPD exacerbations are heterogeneous, and various phenotypes have been proposed which differ in biologic basis, prognosis, and response to therapy. Identification of biomarkers could enable phenotype-driven approaches for the management and prevention of exacerbations. For example, several biomarkers of inflammation can help to identify exacerbations most likely to respond to oral corticosteroids and antibiotics, and patients with a frequent exacerbator phenotype, for whom preventative treatment is appropriate. Reducing the frequency of exacerbations would have a beneficial impact on patient outcomes and prognosis. Preventative strategies include modification of risk factors, treatment of comorbid conditions, the use of bronchodilator therapy with long-acting β2-agonists or long-acting muscarinic antagonists, and inhaled corticosteroids. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying COPD exacerbations will help to optimize use of the currently available and new interventions for preventing and treating exacerbations.

Introduction

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), whether reported/treated or unreported/untreated, have a detrimental and prolonged impact on patients’ health status and outcomes,Citation1–Citation3 and have cumulative negative effects on lung function over time.Citation4 COPD exacerbations are heterogeneous, varying in severity and phenotype, and thus require careful assessment in order to guide management strategies.Citation5,Citation6

Reducing the number of exacerbations that a patient experiences would have a beneficial impact on their daily life, disease outcomes, and prognosis. Strategies to prevent exacerbations include targeting risk factors, addressing comorbid conditions, and bronchodilator therapy with long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) or long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) (used alone or in combination with each other or with an inhaled corticosteroid [ICS]).Citation7

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the currently accepted consensus definition, an update on the assessment of exacerbations, and to outline the latest evidence for selecting treatment and preventative strategies, including approaches based on specific exacerbation subtypes and risk factors.

What are exacerbations?

How do we define exacerbations?

Exacerbations of COPD can be associated with both respiratory (eg, dyspnea and productive cough) and non-respiratory (eg, fatigue and malaise) symptoms.Citation8 The consensus definition of an exacerbation is a sustained worsening of the patient’s condition from the stable state and beyond normal day-to-day variations that is acute in onset and necessitates a change in medication or hospitalization in a patient with underlying COPD.Citation8

COPD exacerbations frequently lead to an increase in health care resource use, according to severity.Citation8,Citation9 For example, mild exacerbations can often be managed in the home but may require increased use of reliever medication, such as inhaled bronchodilators, for worsening symptoms, while moderate exacerbations need treatment with antibiotics and/or corticosteroids. Severe exacerbations require hospitalization for advanced monitoring and potential treatments, including assisted ventilation.Citation8

Exacerbation phenotypes

There is heterogeneity in COPD clinical manifestations, outcomes, and responses to treatment.Citation6 These differences can be used to classify COPD into specific phenotypes that can be used to guide therapeutic decisions.Citation6 Exacerbations in COPD have been shown to be similarly varied, with differing pathology and prognoses, and respond to different management strategies.Citation5,Citation6

Many exacerbations of COPD involve bacterial or viral respiratory infectionsCitation10 and, despite resolution of the infection, have been shown to have a sustained effect on health status.Citation2

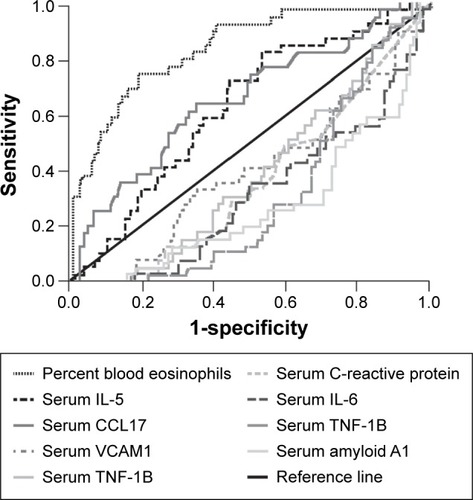

In a study of COPD exacerbation phenotypes, Bafadhel et al identified distinct subtypes that were predominantly related to bacterial or viral infection or elevated eosinophil counts and were associated with 55%, 29%, and 28% of exacerbations, respectively.Citation11 These were clinically indistinguishable but could be identified at the biologic level by the use of biomarkers.Citation11 Peripheral blood eosinophil count was shown to be a valid biomarker for sputum eosinophil-associated exacerbations ().Citation11 Unlike bacterial and eosinophilic phenotypes, viral infection was rarely detected in the stable state, suggesting a strong association of viral infections with exacerbations.Citation11 Patients with COPD and evidence of eosinophilic airway inflammation respond well to corticosteroid therapy.Citation12 Therefore, biomarkers can be informative in identifying phenotypes of COPD that will respond to antibiotics or anti-inflammatory treatment at the onset of an exacerbation.Citation5

Figure 1 Receiver operating characteristic curve illustrating that blood eosinophils are a marker of sputum eosinophil-associated exacerbations.

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; CCL, chemokine ligand; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule.

A “frequent exacerbator” phenotype has been postulated and examined in clinical studies. In the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study of COPD exacerbation susceptibility, approximately 20% of patients with Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 2 disease and as many as 47% of those with stage 4 disease were classified as “frequent exacerbators” (defined as two or more exacerbations annually).Citation13 Risk factors associated with this type of patient include a rapid decline in lung function and respiratory bacterial or viral colonization, although the predictive value of these factors is yet to be ascertained.Citation14 A background of persistent airway and systemic inflammation results in slow recovery and poorer outcomes.Citation14 Interleukin-8 and fibrinogen have been proposed as potential biomarkers of the frequent exacerbator phenotype; however, further studies are required for elucidation.Citation15,Citation16

How do we assess exacerbations?

The variety of symptoms that can worsen during an exacerbation of COPD necessitates the use of standardized and validated instruments to evaluate the frequency, severity, and duration of exacerbations. The EXAcerbation of COPD Tool (EXACT), a patient-reported daily diary, has been used in clinical studies to detect and quantify exacerbations.Citation17 The tool is based on a set of 14 symptoms that characterize an exacerbation, grouped into subscales of chest symptoms, cough and sputum symptoms, breathlessness symptoms, and constitutional items (). A recent study showed that the EXACT tool was effective for evaluating exacerbation severity when compared with the London COPD cohort diary.Citation18

Table 1 Symptomatic components of an exacerbation, evaluated using the EXAcerbation of COPD Tool (EXACT)Citation17

The impact of exacerbations

Exacerbations of COPD have a considerable impact on patients’ health statusCitation2 and exercise capacity,Citation19 and have a cumulative effect on lung function.Citation4

As part of the Gemifloxacin Long-term Outcomes in Bronchitis Exacerbations (GLOBE) study, the time course for recovery of health status in patients with respiratory disease (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ]) and the impact of further exacerbations on time to recovery were assessed over the 6 months following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.Citation2 Following the initial exacerbation, SGRQ scores were worse among the group of patients who experienced subsequent exacerbations during the 6-month follow-up compared with those with no further exacerbation (difference 5.4 units; P=0.002).Citation2 In both groups, the biggest improvement in SGRQ scores occurred within the first 4 weeks after the initial event.Citation2 A long phase of slow improvement then took place over the 6-month course of the study, with the extent of recovery significantly poorer among patients who experienced further exacerbation.Citation2

The short- and long-term impact of exacerbations on exercise capacity was demonstrated by Cote et al.Citation19 Patients in this study who experienced exacerbations showed progressive worsening of 6-minute walking distance over time, with a loss of 74 m reported after 2 years.Citation19 In contrast, the control group, comprising patients who did not experience exacerbations during the study period, showed no significant change from baseline.Citation19 Reduction in activity associated with exacerbations may lead to patients with COPD becoming housebound. Donaldson et al demonstrated a significant decrease in time spent outdoors (−0.16 hour/day/year; P<0.001) by patients with exacerbations, with a significantly more rapid (P=0.011) decline in time spent outdoors evident in those with frequent exacerbations.Citation20 Although these effects are modest, these data demonstrate that frequent exacerbations are associated with a higher likelihood of patients with COPD becoming housebound.Citation20

Exacerbations of COPD also have a cumulative effect on lung function (FEV1). Patients in the 3-year TOward a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH) study of salmeterol plus fluticasone who experienced 0–1.0 moderate to severe exacerbation per year (n=1,862) had a 37% faster decline in lung function (P<0.001) than those with no exacerbations (n=1,306).Citation4 Among those patients who experienced >1.0 moderate to severe exacerbation (n=1,735), the rate of decline in FEV1 was 65% faster (P<0.001).Citation4

Reported vs unreported/untreated exacerbations

Many exacerbations remain unreported and hence untreated by health care professionals, and these also have a substantial impact on patients’ health status.Citation1 In addition, there is a wide geographic variability in the ratio of reported to unreported exacerbations, which may be due to cultural as well as socioeconomic reasons.Citation1

Among a cohort of patients with COPD who had received instruction on reporting worsening symptoms and had regular clinic visits, only 50% of exacerbations were reported to the clinical team when the patient noticed worsening symptoms on 2 consecutive days, even though there were no differences in major symptoms between reported and unreported (identified from the patient diary card at scheduled clinic visits) events.Citation21 During the 6-month, international, randomized Aclidinium To Treat Airway obstruction In COPD patieNts (ATTAIN) trial of aclidinium bromide, a 2.3-fold higher number of exacerbations per patient per year was recorded using the EXACT diary card (1.39 events per patient per year), compared with the number reported based on health care resource use, ie, increased symptoms on ≥2 consecutive days requiring a change in medication (0.60 event per patient per year).Citation1

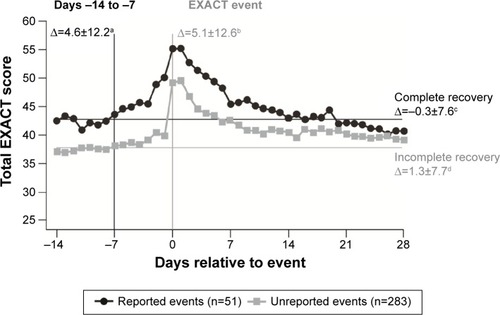

Data from the ATTAIN study also demonstrated important differences between reported and unreported exacerbations in terms of impact on health status and recovery post-treatment.Citation1 The absolute health status score (SGRQ) was worse, the rate of deterioration in FEV1 was faster, and patients recovered more slowly (EXACT scores) with unreported compared with reported exacerbations ().Citation1 A reduction in health status score at the time of the exacerbation did not influence whether or not an exacerbation was reported.Citation1 The impact of unreported exacerbations on long-term disease progression is still unknown; however, it is clear that these unreported events have important short- and medium-term consequences on symptoms and health status.Citation1

Figure 2 EXAcerbations of COPD Tool (EXACT) scores for reported (identified by health care resource utilization and by EXACT) and unreported (identified by EXACT only) exacerbations.Citation1

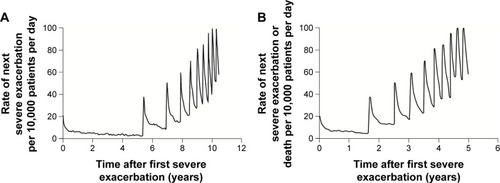

Severe exacerbations

A long-term follow-up study of a cohort of patients with COPD found that 50% of patients died within 3.6 years of their first hospitalization for COPD exacerbation.Citation3 Following the first severe COPD exacerbation, a period of stable risk was identified between the first and second exacerbations.Citation3 However, each subsequent recurrence of a severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization increased the risk of a subsequent event and death (), with subsequent events being of increasing severity.Citation3 This highlights the current need for improvement in approaches to both the prevention and treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD.

Figure 3 Natural history of COPD in a cohort of 73,106 patients after first hospitalization for a severe exacerbation, showing (A) rate of next severe exacerbation and (B) rate of next severe exacerbation or death per 10,000 patients per day.Citation3

Management of exacerbations

Systemic corticosteroid therapy

Current evidence-based guidelines for the management of COPD state that in the absence of contraindications, oral corticosteroids should be used in conjunction with other therapies in all patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations.Citation22 This recommendation is based on randomized controlled trials,Citation23,Citation24 but it is important to note that the effects are relatively small and need to be balanced against the potential for harm. Moreover, there is only limited evidence favoring the use of corticosteroids for patients with severe exacerbations of COPD who require admission to intensive care.Citation25 The guidelines for the management of COPD do not make strong recommendations on the use of systemic corticosteroids for exacerbations for outpatients, rather they should be “considered” for outpatients with a significant increase in breathlessness that interferes with daily activities.Citation22,Citation26 Overall, there is a lack of data on the use of systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of exacerbations in the outpatient setting, compared with hospitalized patients.

A Cochrane analysis found that systemic corticosteroid use led to fewer treatment failures, a shorter duration of hospitalization, significant lung function (FEV1) benefits, and improvements in breathlessness, but with no significant effect on mortality.Citation27 In addition, there was an increased risk of an adverse event, in particular hyperglycemia, associated with systemic corticosteroid use.Citation27 The 2015 update to the GOLD strategy document recommends treatment with oral prednisone 40 mg per day for only 5 days for hospitalized patients.Citation26 This recommendation is based on the REDuction in the Use of Corticosteroids in Exacerbated COPD (REDUCE) study, which demonstrated that, in patients presenting to the emergency department with an acute exacerbation of COPD, a 5-day regimen with oral prednisone 40 mg is non-inferior to 14 days’ treatment, with regard to re-exacerbation within 6 months’ follow-up.Citation28 However, there were no significant differences in glucocorticoid-related, short-term adverse effects between the treatment groups.Citation28 It is also likely that lower doses of systemic steroids are associated with fewer side effects and a better benefit/risk profile than higher doses in patients hospitalized in intensive care units.Citation29

A phenotype-guided treatment approach could be appropriate to better target the use of corticosteroids in patients to prevent and treat COPD exacerbations. The presence of an elevated sputum eosinophil count in patients with stable COPD has been associated with a good response to prednisolone.Citation12 As such, a blood eosinophil count >2% has been suggested as an easily obtainable biomarker for predicting effectiveness of oral corticosteroids in patients with exacerbations.Citation5 A recent meta-analysis of outcomes with placebo and prednisolone showed that prednisolone reduced treatment failure rates at 30 days from 66% to 11%.Citation5 In contrast, prednisolone was not effective in patients with a blood eosinophil count of ≤2%, and one study suggested that treatment failure rates were significantly worse with antibiotics and prednisolone compared with antibiotics and placebo.Citation30 Although confirmation of these findings is required, they indicate that blood eosinophil count could potentially be used as a biomarker to direct corticosteroid therapy for exacerbations and could help avoid unnecessary exposure to systemic corticosteroids. Fractional excretion of nitric oxide has been used to identify airway inflammation in other respiratory conditions, and preliminary studies have demonstrated that this could be used as a potential marker of response to corticosteroids in patients with COPD.Citation31–Citation33

Antibiotic therapy

Approximately 50% of COPD exacerbations are associated with detection of bacteria in the sputum,Citation11 and current guidelines recommend antibiotic therapy when patients present with the three cardinal symptoms (increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence), or with increased sputum purulence and one other cardinal symptom.Citation26

A meta-analysis of antibiotic use in COPD exacerbations revealed inconsistent effects, with more pronounced positive effects on treatment success in hospitalized patients vs outpatients, but no significant effects on mortality or length of hospital stay.Citation34 However, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of hospitalized patients who needed mechanical ventilation for COPD exacerbations found that mortality significantly increased from 4% to 22% in those patients randomized to no antibiotic.Citation35 Therefore, antibiotics should not be withheld in patients with severe exacerbations who require ventilator support.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a potentially useful bio-marker for predicting which exacerbations may benefit from antibiotic therapy and for selecting those that might resolve without antibiotic intervention.Citation36 In patients with exacerbations and CRP levels >50 mg/L, a significantly higher rate of clinical success for doxycycline treatment was demonstrated vs placebo.Citation36 The same study concluded that procalcitonin may not be sufficiently sensitive for use as a biomarker for response to antibiotics in patients with COPD exacerbations.Citation36 Therefore, the use of CRP as a biomarker could help to avoid unnecessary use of antibiotic therapy that can lead to adverse effects and development of bacterial resistance.Citation37

Non-invasive ventilation and oxygen therapy

Non-invasive ventilation improves gas exchange by providing ventilator support through the upper airway using a mask, and is recommended for severe COPD exacerbations in patients with respiratory acidosis (arterial pH ≤7.35) when added to standard therapy.Citation22,Citation26 Early use of this therapy following hospitalization has been shown to reduce the need for intubation and improves survival in patients with COPD in a randomized clinical trial.Citation38,Citation39 However, there is some controversy on this subject because another recent study did not detect any benefit of non-invasive ventilation.Citation40

Oxygen therapy has also been shown to reduce hypoxia associated with exacerbations of COPD; however, careful titration of oxygen levels is crucial, particularly in patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure.Citation41

Home management

Although exacerbations have a considerable clinical impact, some patients could be safely treated at home.Citation22 This approach would reduce demand for hospital beds and would also take patients’ preferences for home- or hospital-based treatment into consideration.Citation22,Citation42 Current guidance acknowledges however that it may be difficult to determine which patients home management is appropriate for, although resources available and poor prognostic indicators (eg, acidosis) will influence the decision.Citation22

Roche et al developed a scoring system, based on variables at admission to hospital for COPD exacerbation (age, exacerbation severity, and dyspnea), that may be useful for predicting risk of death and requirement for post-hospital support.Citation43 A recent independent study by the same authors suggests that this score may prove useful in clinical practice, but further validation is still necessary.Citation44 A Cochrane review, evaluating early hospital discharge combined with a domiciliary respiratory nurse for managing acute COPD exacerbations as an alternative to hospitalization, found that hospital re-admissions were reduced with the “hospital at home” approach (risk ratio 0.76; P=0.04).Citation42 Furthermore, there were early indications for reduced risk of mortality (risk ratio 0.66; P=0.07).Citation42 Evidence is lacking though for a strongly positive association between the “hospital at home” approach and other outcomes (lung function, patient satisfaction, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness).Citation42 Furthermore, only a minority (25%) of patients were eligible for the “hospital at home” approach, based on lung function, comorbidities, and other factors (eg, confusion).Citation42

Preventing exacerbations

There is evidence that COPD exacerbations cluster together, and a high-risk period for recurrence has been identified in the first 8 weeks following an initial event.Citation45 This may have important implications for preventative strategies.

Risk factors as targets for intervention

Risk factors for COPD are also risk factors for the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and as such, are potential targets for intervention. These include smoking cessation, prevention of respiratory infections, and avoiding a rapid decline in lung function.Citation14 Decreased FEV1 in particular is associated with increased symptoms and heightened inflammatory responses, thus targeting lung mechanics may alter the risk of an exacerbation.Citation46

Inhaled corticosteroids

ICS is commonly prescribed to patients with COPD, with the primary goal of reducing exacerbations. There is consistent evidence that ICS treatment reduces exacerbation frequency by ∼25% either when prescribed alone or in combination with a LABA.Citation47,Citation48 Current guidelines recommend ICS therapy in patients with two or more COPD exacerbations in the last year, one severe exacerbation, or impaired lung function such that an exacerbation risk is deemed to be present.Citation26 Traditionally, a high dose of ICS (eg, fluticasone dipropionate 500 µg bid) is prescribed; however, there is little high-quality information available on the dose−response relationship. A study of once-daily fluticasone furoate, at a dosage of 50−100 µg daily in addition to vilanterol, demonstrated a progressive treatment benefit, with no apparent benefit above this dose.Citation49 The potential for ICS to cause pneumonia is a concern; this is a function of dose and duration of treatment.Citation50 Currently, there is a great deal of interest in the possibility that this risk might be mitigated using the blood eosinophil count as a biomarker of likely response to ICS. Two studies have shown that the risk of exacerbation and the benefits of ICS increase progressively as the blood eosinophil count increases above 2% (equivalent to a count of 0.15×109/L), whereas patients with a blood eosinophil count <2% had little evidence of benefit from ICS.Citation51,Citation52 However, the elevated risk of pneumonia associated with ICS use was independent of eosinophil count; therefore, patients with a blood eosinophil count of <2% had minimal benefit from the ICS but increased risk of pneumonia.Citation51

Bronchodilator treatment

The nature of the exacerbation and the COPD phenotype dictate the extent of mechanical and anti-inflammatory intervention required; patients with more mucus and airway/lung function impairment are more likely to benefit from anti-inflammatory therapy, whereas patients with greater mechanical impairment are likely to benefit from bronchodilator therapy, even without corticosteroids.Citation53

The Prevention Of Exacerbations with Tiotropium in COPD (POET) study showed that long-acting bronchodilator therapy with the anti-cholinergic drug tiotropium was superior to a LABA, salmeterol, in preventing exacerbations in patients with moderate to severe COPD at risk of exacerbation.Citation54 Time to first exacerbation was increased (187 vs 145 days; hazard ratio 0.83; P<0.001), and the annual number of moderate or severe exacerbations was reduced (0.64 vs 0.72; P=0.02) with tiotropium compared with salmeterol.Citation54 The concomitant use of ICS showed no effect on these outcomes.Citation54 Interestingly, the response to salmeterol can be influenced by the β2-adrenergic receptor genotype.Citation55 Patients with the Arg16Arg genotype had a reduced risk of exacerbation in response to salmeterol than those with the Arg16Gly and Gly16Gly genotypes.Citation55

The ATTAIN study investigated the efficacy of the inhaled LAMA aclidinium in moderate to severe COPD.Citation1 Regardless of whether COPD exacerbations were reported (recorded by health care resource utilization) or unreported (recorded by EXACT), aclidinium treatment demonstrated a similar clinical benefit, instigating a 29%–33% reduction in annualized rates of exacerbation per patient per year.Citation1

In the SPARK study, the efficacy of the dual LAMA/LABA glycopyrronium/indacaterol was compared with glycopyrronium and open-label tiotropium in patients with severe or very severe COPD.Citation56 Approximately 75% of patients were also using a concomitant ICS. Glycopyrronium/indacaterol reduced the annualized rate of COPD exacerbations (all severities) compared with glycopyrronium or tiotropium monotherapy, indicating that combining a β2-agonist with an anti-cholinergic agent reduces exacerbation frequency.Citation56 This dual bronchodilation approach may be clinically beneficial for patients with severe disease, and may circumvent the genetic variability that renders patients less susceptible to single agents.Citation56

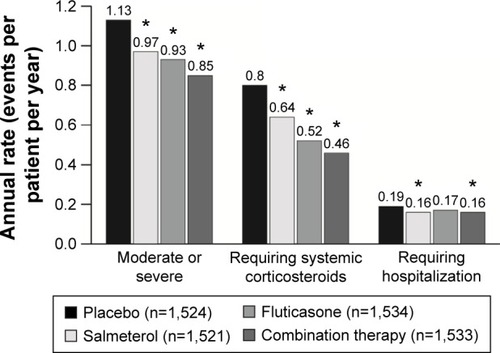

The annual incidence of moderate or severe exacerbations, systemic corticosteroid prescriptions, and hospitalizations were reduced significantly in the TORCH study with both the β2-agonist salmeterol and corticosteroid fluticasone.Citation48 The effects were greater in patients who administered the drugs in combination, suggesting that multiple underlying factors may be involved in determining response to therapy ().Citation48 However, the recently published Withdrawal of Inhaled Steroids During Optimized bronchodilator Management (WISDOM) study specifically investigated impact on exacerbation frequency caused by the withdrawal of ICS and found that ICS use did not alter the risk of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations.Citation57 These results should be interpreted with caution, because only those patients who had at least one exacerbation in the previous year met the recruitment criteria, meaning that those responding poorly to ICS were more likely to be represented in the study population.

Figure 4 Annual rate of exacerbations, systemic corticosteroid prescriptions, and hospitalizations in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of combination therapy with a long-acting β-agonist and inhaled corticosteroid in patients with COPD.

Other approaches to reduce exacerbation risk

In addition to bronchodilators, other classes of drugs have been shown to reduce exacerbation risk in specific subsets of patients with COPD. A randomized trial of the macrolide azithromycin, taken daily for 1 year in addition to usual therapy, demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of exacerbations in patients with COPD at increased risk of exacerbation.Citation58 This effect was greatest in the subgroup of patients requiring both antibiotic and corticosteroid treatment, and in patients who were non- or ex-smokers.Citation59 Similarly, a study of the oral anti-inflammatory agent roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has demonstrated a reduction in exacerbations frequency in patients with severe COPD and a history of exacerbations.Citation60 Two Chinese clinical studies showed that N-acetylcysteine and the mucolytic agent carbocisteine, both of which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, may reduce the frequency of exacerbations of COPD in Chinese patients.Citation61,Citation62

There is evidence that pneumococcal and annual influenza vaccinations reduce the risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in patients with COPD, and it is recommended that these are offered to patients with COPD.Citation22,Citation26,Citation63,Citation64

Treating comorbid conditions

Comorbidities of COPD, such as cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, depression, and osteoporosis, are associated with increased susceptibility to exacerbations and can also contribute to how COPD develops.Citation14 Cardiovascular disease is the most common group of comorbidities, with ischemic heart disease estimated to affect around 20% of patients with COPD.Citation14 Severe COPD exacerbations may involve underlying comorbidities, particularly endocrine and cardiovascular conditions. For example, systemic inflammation and elevated CRP, both features of COPD, have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk.Citation14 Patients with severe airflow obstruction have even poorer cardiac outcomes than those with systemic inflammation; however, those with both impaired lung function and systemic inflammation have a significantly worse cardiovascular outcome in terms of the cardiac infarction injury score.Citation65

Preventative strategies should therefore consider these comorbid conditions. Although there is sparse evidence from randomized trials demonstrating that treating comorbidities improves COPD, several treatment approaches have shown a benefit in observational studies. Statin therapy may help to improve outcomes in patients with COPD and peripheral arterial diseaseCitation66 and other cardiovascular comorbidities.Citation67 However, a recent study of simvastatin in patients with moderate to severe COPD without metabolic/cardiovascular indication for statins did not observe any reduction in COPD exacerbations.Citation68 There is evidence suggesting that the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta blockers may reduce mortality in patients with COPD and cardiovascular comorbidities.Citation69,Citation70

Given the prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities among patients with COPD, cardiovascular safety of COPD therapy also needs to be considered. For example, in a pooled analysis of long-term studies in COPD, the oral anti-inflammatory agent roflumilast has not been associated with major cardiovascular events in long-term studies.Citation71

A better understanding of the mechanisms triggering exacerbations will help to determine the optimal use of preventative strategies in future.

Conclusion

Exacerbations of COPD have a substantial impact on health status and cumulative effects on lung function. Many exacerbations are unreported, which not only underestimates their incidence, but may also lead to under-treatment and poorer recovery. Distinct COPD exacerbation subtypes have been proposed, which may differ in prognosis and response to treatment. The management of COPD should involve phenotype-directed strategies, and efforts have been made to identify biomarkers that could help guide treatment. In addition, efforts to prevent exacerbations should aim to reduce risk factors and manage comorbid conditions. Understanding the mechanisms by which COPD exacerbations occur may determine the best course of preventative strategy and lead to development of novel interventions.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Kirsteen Munn on behalf of Complete Medical Communications, funded by Almirall S.A., Barcelona, Spain.

Disclosure

Professor Pavord has previously received speaker’s fees and honoraria from Aerorine, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dey, GlaxoSmithKline, Napp, Novartis, and Respivert. Professor Jones has previously received speaker fees from and has served on advisory boards for Almirall, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche, and Spiration, and has received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline. All fees were contracted via his institution. Professor Burgel has previously received lecture fees and honoraria from, and served on advisory boards for, Air Liquide, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer, and has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer. Professor Rabe has consulted for, participated in advisory board meetings with, and received lecture fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Pfizer, Novartis, Takeda, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and GlaxoSmithKline. Professor Rabe has also received grants from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffmann-La Roche, Altana, and GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- JonesPWLamarcaRChuecosFCharacterisation and impact of reported and unreported exacerbations: results from ATTAINEur Respir J20144451156116525234803

- SpencerSJonesPWTime course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitisThorax200358758959312832673

- SuissaSDell’AnielloSErnstPLong-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortalityThorax2012671195796322684094

- CelliBRThomasNEAndersonJAEffect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178433233818511702

- BafadhelMMcKennaSTerrySBlood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861485522447964

- HanMKAgustiACalverleyPMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPDAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182559860420522794

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD Executive SummaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- Rodriguez-RoisinRToward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbationsChest20001175 Suppl 2398S401S10843984

- BurgeSWedzichaJACOPD exacerbations: definitions and classificationsEur Respir J20032141 Suppl46s53s

- SethiSMurphyTFInfection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359222355236519038881

- BafadhelMMcKennaSTerrySAcute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkersAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184666267121680942

- BrightlingCEMonteiroWWardRSputum eosinophilia and short-term response to prednisolone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trialLancet200035692401480148511081531

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- WedzichaJABrillSEAllinsonJPDonaldsonGCMechanisms and impact of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMC Med20131118123945277

- BhowmikASeemungalTASapsfordRJWedzichaJARelation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbationsThorax200055211412010639527

- GroenewegenKHPostmaDSHopWCWieldersPLSchlosserNJWoutersEFIncreased systemic inflammation is a risk factor for COPD exacerbationsChest2008133235035718198263

- JonesPWChenWHWilcoxTKSethiSLeidyNKCharacterizing and quantifying the symptomatic features of COPD exacerbationsChest201113961388139421071529

- MackayAJDonaldsonGCPatelARSinghRKowlessarBWedzichaJADetection and severity grading of COPD exacerbations using the exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Tool (EXACT)Eur Respir J201443373574423988767

- CoteCGDordellyLJCelliBRImpact of COPD exacerbations on patient-centered outcomesChest2007131369670417356082

- DonaldsonGCWilkinsonTMHurstJRPereraWRWedzichaJAExacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171544645215579723

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCPaulEABestallJCJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981575 Pt 1141814229603117

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [homepage on the Internet]NICE Clinical Guideline 101, Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care (partial update) [updated 2010] Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG101Accessed October 21, 2015

- DaviesLAngusRMCalverleyPMOral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trialLancet1999354917745646010465169

- NiewoehnerDEErblandMLDeupreeRHEffect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study GroupN Engl J Med1999340251941194710379017

- AbrougFKrishnanJAWhat is the right dose of systemic corticosteroids for intensive care unit patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations? A question in search of a definitive answerAm J Respir Crit Care Med201418991014101624787061

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [homepage on the Internet]Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [updated 2015] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015_Feb18.pdfAccessed October 21, 2015

- WaltersJATanDJWhiteCJGibsonPGWood-BakerRWaltersEHSystemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20149CD00128825178099

- LeuppiJDSchuetzPBingisserRShort-term vs conventional glucocorticoid therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the REDUCE randomized clinical trialJAMA2013309212223223123695200

- KiserTHAllenRRValuckRJMossMVandivierRWOutcomes associated with corticosteroid dosage in critically ill patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med201418991052106424617842

- BafadhelMDaviesLCalverleyPMAaronSDBrightlingCEPavordIDBlood eosinophil guided prednisolone therapy for exacerbations of COPD: a further analysisEur Respir J201444378979124925917

- DonohueJFHerjeNCraterGRickardKCharacterization of airway inflammation in patients with COPD using fractional exhaled nitric oxide levels: a pilot studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014974575125053884

- DummerJFEptonMJCowanJOPredicting corticosteroid response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using exhaled nitric oxideAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180984685219661244

- KunisakiKMRiceKLJanoffENRectorTSNiewoehnerDEExhaled nitric oxide, systemic inflammation, and the spirometric response to inhaled fluticasone propionate in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective studyTher Adv Respir Dis200822556419124359

- VollenweiderDJJarrettHSteurer-SteyCAGarcia-AymerichJPuhanMAAntibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201212CD01025723235687

- NouiraSMarghliSBelghithMBesbesLElatrousSAbrougFOnce daily oral ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet200135892982020202511755608

- DanielsJMSchoorlMSnijdersDProcalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPDChest201013851108111520576731

- HerathSCPoolePProphylactic antibiotic therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Cochrane Database Syst Rev201311CD00976424288145

- PlantPKOwenJLElliottMWEarly use of non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on general respiratory wards: a multicentre randomised controlled trialLancet200035592191931193510859037

- PlantPKOwenJLParrottSElliottMWCost effectiveness of ward based non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: economic analysis of randomised controlled trialBMJ2003326739695612727767

- StruikFMSprootenRTKerstjensHANocturnal non-invasive ventilation in COPD patients with prolonged hypercapnia after ventilatory support for acute respiratory failure: a randomised, controlled, parallel-group studyThorax201469982683424781217

- BrillSEWedzichaJAOxygen therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491241125225404854

- JeppesenEBrurbergKGVistGEHospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20125CD00357322592692

- RocheNZureikMSoussanDNeukirchFPerrotinDPredictors of outcomes in COPD exacerbation cases presenting to the emergency departmentEur Respir J200832495396118508819

- RocheNChavaillonJMMaurerCZureikMPiquetJA clinical in-hospital prognostic score for acute exacerbations of COPDRespir Res2014159925158759

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKGoldringJJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJATemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179536937419074596

- DonaldsonGCWedzichaJACOPD exacerbations. 1: EpidemiologyThorax200661216416816443707

- BurgePSCalverleyPMJonesPWSpencerSAndersonJAMaslenTKRandomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trialBMJ200032072451297130310807619

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- DransfieldMTBourbeauJJonesPWOnce-daily inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol versus vilanterol only for prevention of exacerbations of COPD: two replicate double-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trialsLancet Respir Med20131321022324429127

- SuissaSPatenaudeVLapiFErnstPInhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumoniaThorax201368111029103624130228

- PascoeSLocantoreNDransfieldMTBarnesNCPavordIDBlood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trialsLancet Respir Med20153643544225878028

- SiddiquiSHGuasconiAVestboJBlood eosinophils: a bio-marker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015192452352526051430

- GonemSRajVWardlawAJPavordIDGreenRSiddiquiSPhenotyping airways disease: an A to E approachClin Exp Allergy201242121664168323181785

- VogelmeierCHedererBGlaabTTiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2011364121093110321428765

- RabeKFFabbriLMIsraelEEffect of ADRB2 polymorphisms on the efficacy of salmeterol and tiotropium in preventing COPD exacerbations: a prespecified substudy of the POET-COPD trialLancet Respir Med201421445324461901

- WedzichaJADecramerMFickerJHAnalysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group studyLancet Respir Med20131319920924429126

- MagnussenHDisseBRodriguez-RoisinRWithdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2014371141285129425196117

- AlbertRKConnettJBaileyWCAzithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2011365868969821864166

- HanMKTayobNMurraySPredictors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation reduction in response to daily azithromycin therapyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2014189121503150824779680

- CalverleyPMRabeKFGoehringUMKristiansenSFabbriLMMartinezFJRoflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trialsLancet2009374969168569419716960

- ZhengJPKangJHuangSGEffect of carbocisteine on acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PEACE Study): a randomised placebo-controlled studyLancet200837196292013201818555912

- ZhengJPWenFQBaiCXTwice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trialLancet Respir Med20142318719424621680

- PoolePJChackoEWood-BakerRWCatesCJInfluenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20004CD00273311034751

- WaltersJASmithSPoolePGrangerRHWood-BakerRInjectable vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201011CD00139021069668

- SinDDManSFWhy are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCirculation2003107111514151912654609

- van GestelYRHoeksSESinDDEffect of statin therapy on mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease and comparison of those with versus without associated chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Cardiol2008102219219618602520

- YoungRPHopkinsRJUpdate on the potential role of statins in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its co-morbiditiesExpert Rev Respir Med20137553354424138695

- CrinerGJConnettJEAaronSDSimvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPDN Engl J Med2014370232201221024836125

- MortensenEMCopelandLAPughMJImpact of statins and ACE inhibitors on mortality after COPD exacerbationsRespir Res2009104519493329

- QuintJKHerrettEBhaskaranKEffect of beta blockers on mortality after myocardial infarction in adults with COPD: population based cohort study of UK electronic healthcare recordsBMJ2013347f665024270505

- WhiteWBCookeGEKoweyPRCardiovascular safety in patients receiving roflumilast for the treatment of COPDChest2013144375876523412642