Abstract

A patient with type 2 diabetes, retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy presented with severe right distal thigh pain, which awoke him from sleep. He was diagnosed with musculoskeletal pain and discharged home. Two days later, the severity of pain increased in his right thigh and, subsequently, he developed pain in the proximal lateral aspect of his left thigh, for which he returned to hospital. He had elevated creatine kinase and myoglobin levels. An ultrasound of the right thigh identified a loss of definition of the normal muscular striations and subcutaneous edema. On MRI, the axial STIR image demonstrated extensive T2 hyperintensity in the right vastus medialis and left vastus lateralis, consistent with the diagnosis of diabetic muscle infarction (DMI). This presentation emphasizes the need for a thorough patient history and physical examination, and the importance of directed imaging for the prompt diagnosis of DMI.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Background

Diabetic muscle infarction (DMI) poses a diagnostic dilemma, due to its rare presentation and large differential diagnosis. Diabetic neuropathy is well recognized, with the typical symptoms of distal pain and paresthesiae in the feet and lower legs. Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy may present with acute onset severe proximal thigh pain and weakness.Citation1 Generalized proximal weakness can also occur as part of the motor presentation of diabetic neuropathy, in association with severe vitamin D deficiency, or hypothyroidism. Rhabdomyolysis, especially due to statins, should be considered when weakness is accompanied by severe and constant pain.

Presenting complaint

A 50-year-old male with type 2 diabetes presented with unilateral, then bilateral thigh pain with localized swelling and tenderness.

History of presenting complaint

Four days prior to admission, the patient had awoken from sleep with acute onset, severe localized pain (VAS =7/10) in the distal and medial aspect of the right thigh. The pain was exacerbated by leg movement and walking. There were no associated prodromal symptoms. He denied a history of physical trauma, excessive exertion, or strenuous sporting activity. He was diagnosed with “muscle strain” and discharged home with analgesia and advised to rest. Two days later, severe pain developed in the proximal lateral part of his left thigh, the pain in the right thigh had increased in severity, and he had developed localized swelling and erythema.

Past medical history

The patient had type 2 diabetes mellitus for 18 years, hypertension for 5 years, and had significant proteinuria with chronic kidney disease (CKD). He had undergone laser photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy (DR) in both eyes 12 years ago, and developed blindness in the left eye due to advanced proliferative DR. The patient had severe neuropathy and had previously undergone a surgical incision to drain pus from an infected left foot ulcer to remove glass foreign bodies.

Medication

Insulin Mixtard 30/70, 33 units am and 30 units pm

Amlodipine 5 mg once a day

Omeprazole 20 mg once daily

Vitamin D3, 50,000 units (1.25 mg) twice weekly

Bisacodyl 5 mg once daily

Bulk laxative powder 3.5 g once daily

Allergies

None elicited.

Family history

Maternal history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Social history

The patient was married and retired. He was a non-smoker and did not drink alcohol.

Review of systems on admission

Patient distress was apparent due to intense bilateral thigh pain. There was no history of fever, night sweats or chills, and no recent weight loss. He had visual loss in the left eye due to severe DR. Early morning nausea and vomiting had occurred daily 1 week prior to admission. Pain had limited his ability to walk and he had avoided climbing stairs as it exacerbated the discomfort.

Physical examination

Vital signs: temperature 36.5°C, pulse 75/minute, respiratory rate 14/minute, supine blood pressure 150/80, weight: 95 kg, height: 182 cm, BMI: 28.7 kg/m2.

The patient was awake, alert, and oriented for time, place, and person. Cranial nerves were intact, and his left eye perceived only light and dark, with pupils equal and reactive to light and accommodation. Fundoscopy confirmed cotton wool exudates in both eyes. Hearing appeared normal in both ears, and his gag reflex was normal.

There was no clubbing, cyanosis, or pedal edema. He had localized erythema and swelling of the medial aspect of the right distal thigh and lateral aspect of the left proximal thigh, with severe tenderness on palpation of the swollen areas. Neurological examination of the lower limbs demonstrated reduced light touch sensation over both feet, with normal Babinski responses. Muscle strength in the upper extremities was normal (Medical Research Council Scale for muscle strength =5/5). Assessment of muscle strength in both legs was limited by intense leg pain, which markedly reduced knee flexion in both legs. His gait could not be assessed, due to severe pain on standing.

Laboratory investigations

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatine kinase, and myoglobin levels were elevated, and there was evidence of chronic anemia and CKD with poor glycemic control ().

Table 1 Laboratory investigations

Imaging

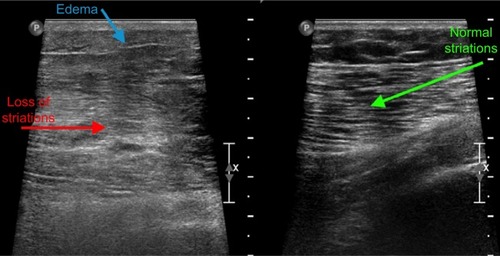

A plain X-ray of his thighs, to exclude an underlying fracture, demonstrated a subtle increased density in the soft tissue of both, but was otherwise unremarkable. Targeted ultrasound of both thighs () was undertaken to exclude a muscle tear, or the presence of infection with abscess formation. There was a loss of striations in the skeletal muscles in the right thigh (red arrow), with generalized, particularly subcutaneous edema (blue arrow). The left side demonstrated normal linear muscle striations.

Figure 1 Ultrasound scan targeted on the thigh demonstrates some loss of definition of the normal muscular striations on the right side (red arrow), with an increase in generalized edema, particularly subcutaneous edema (blue arrow).

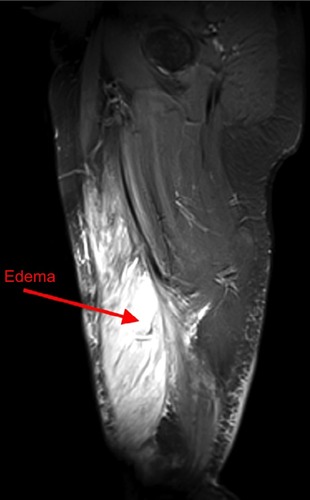

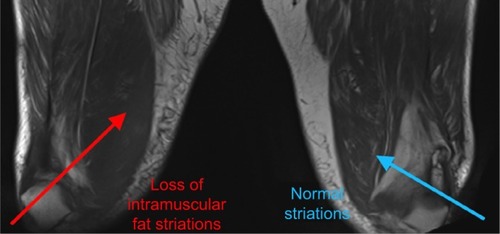

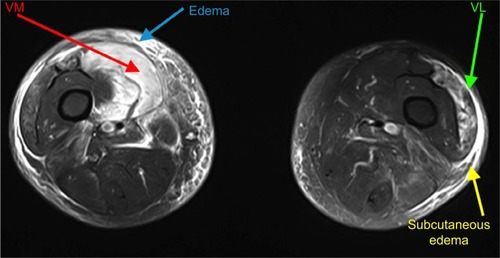

A coronal T1 (non-fat saturated) scan, without contrast, demonstrated right-sided muscle swelling combined with a subtle loss of intramuscular fat striations (red arrow) when compared with the contralateral side (blue arrow) (). Axial STIR imaging demonstrated extensive T2 hyperintensity in the right thigh muscles, in keeping with extensive edema. The right vastus medialis muscle was affected (red arrow), and adjacent right-sided musculature was also involved to a lesser extent, with extensive subcutaneous edema (blue arrow). The left side primarily involved the vastus lateralis muscle (green arrow) and had accompanying subcutaneous edema (yellow arrow) (). The sagittal STIR image confirmed edema in the right vastus medialis (red arrow) ().

Figure 2 Coronal T1 (non-fat saturated) MRI scan demonstrates right sided muscular swelling combined with subtle loss of the intramuscular fat striations (red arrow) when compared with the contralateral side (blue arrow).

Figure 3 Axial STIR image demonstrates extensive T2 hyperintensity in the right thigh musculature, in keeping with extensive edema.

Doppler ultrasound of the upper and lower legs excluded deep vein thrombosis. A chest X-ray showed a normal cardiothoracic ratio, albeit with mild bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, but no evidence of heart failure. An EKG showed a normal sinus rhythm with no axis deviation. Echocardiography revealed mild inferior cardiac wall hypokinesia, normal left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction of 55%, grade 2 left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left atrial enlargement, mild septal hypertrophy, a right ventricular systolic pressure of 26 mm Hg, and a mild pericardial effusion. Ultrasound of the kidneys demonstrated normal renal size with no evidence of hydronephrotic obstruction.

Discussion

DMI commonly presents with pain and swelling in the proximal lower limb muscles due to spontaneous infarction of skeletal muscle, but is not related to arterial occlusion.Citation2–Citation8 It characteristically presents in patients with a long duration of either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, often accompanied by other microvascular complications, particularly CKD, although the outcomes are not different to those with normal renal function.Citation9 It may rarely be painless and can occur in the distal lower limb.Citation10–Citation12 The differential diagnosis includes inflammatory myopathy; infection; polymyositis; dermatomyositis; deep vein thrombosis; trauma; soft tissue hemorrhage; necrotizing fasciitis; and diabetic lumbarsacral radiculoplexopathy.Citation1,Citation13 Our patient had a long duration of type 2 diabetes with poor glycemic control (HbA1c =10.4%), and evidence of all the long-term microvascular complications. Interestingly, he had an elevated creatine kinase and serum myoglobin, indicative of significant muscle pathology, which has previously been shown to be only mildly elevated.Citation14 He did have significantly impaired renal function, but was not on a statin, excluding statinrelated rhabdomyolysis.

MRI imaging is the diagnostic modality of choice.Citation15–Citation17 The patient had typical changes on his MRI, the affected muscle showing a heterogeneous appearance with hyperintense signals on T2-weighted, STIR sequences, and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images with loss of normal fatty intramuscular septae, and subcutaneous and perifascial edema.Citation5,Citation15–Citation18 Muscle biopsy is not recommended, but typically shows muscle fiber necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltrates, and hyalinization of the blood vessels with luminal narrowing.Citation14

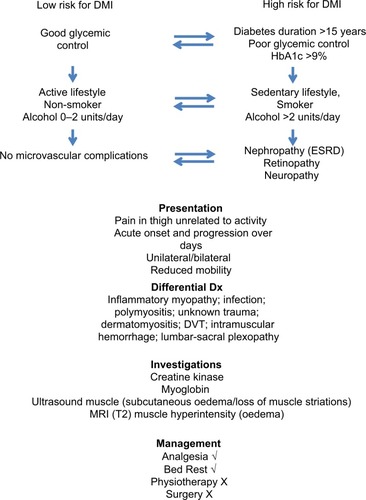

There are currently no clear recommendations in the management of DMI, due to a lack of prospective studies. Indeed, a recent systematic review concluded that the literature on DMI is limited to case reports and case series, with very few prospective studies in relation to management.Citation13 The authors identified 110 peer-reviewed publications on “Diabetic muscle infarction”, published between 1972 and 2018. Previous articles have outlined the presentation and complications of DMI, but none have provided a decision tree or an algorithm on the management of DMI. The authors developed a decision tree identifying those at highest risk of DMI, and indicated the relevant investigations and management for DMI ().

Figure 5 Decision tree for the diagnosis and management of diabetic muscle infarction.

A limited retrospective analysis showed that, when comparing surgery, physiotherapy, and bed rest, the mean time to recovery from DMI being diagnosed was 149, 71, and 43 days, and the mean time to recurrence was 30, 107, and 297 days, with a recurrence rate of 57%, 44%, and 24%, respectively, indicating that bed rest is the best treatment option.Citation19 Surgery should be avoided as it is associated with increased morbidity and delayed recovery.Citation20 Optimization of glycemic control and vascular risk factors is recommended, but is not supported by evidence.

Conclusion

DMI in a patient with diabetes is often misdiagnosed. A careful history is imperative, particularly when the onset of pain is acute and severe, without associated trauma. MRI is the investigation of choice, and an invasive muscle biopsy is unnecessary.

Patient’s perspective

Neither the patient nor the initial ER physicians had linked the proximal limb pain to diabetes, as diabetic neuropathy typically presents with distal symmetrical dysesthesia and paresthesia.Citation1 However, the patient questioned the diagnosis of “muscle strain”, especially as the pain awoke him from sleep, was not relieved by conventional analgesia, and then developed in the other thigh.

Confidentiality

The patient provided verbal and written, informed consent for the use of medical information for publication.

Acknowledgments

The publication of this article was funded by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Pop-Busui R Boulton AJ Feldman EL Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American diabetes association Diabetes Care 2017 40 1 136 154 27999003

- Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital Weekly clinico-pathological exercises. Case 29-1997. A 54-year-old diabetic woman with pain and swelling of the leg N Engl J Med 1997 337 12 839 845 9297115

- Ali O Narshi C Khanna M Roncaroli F Abraham S A painful swollen thigh in a diabetic patient: Diabetic myonecrosis Lancet 2014 383 9931 1860 24856030

- Arroyave JA Aljure DC Cañas CA Vélez JD Abadía FB Diabetic muscle infarction: two cases: one with recurrent and bilateral lesions and one with usual unilateral involvement J Clin Rheumatol 2013 19 3 126 128 23519188

- Chason DP Fleckenstein JL Burns DK Rojas G Diabetic muscle infarction: radiologic evaluation Skeletal Radiol 1996 25 2 127 132 8848740

- Chebbi W Jerbi S Klii R Alaya W Mestiri S Zantour B Sfar MH Multifocal diabetic muscle infarction: a rare complication of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus Intern Med 2014 53 18 2091 2094 25224194

- Cumberledge J Kumar B Rudy D Life R Risking life and limb: a case of spontaneous diabetic muscle infarction (diabetic myonecrosis) J Gen Intern Med 2016 31 6 696 698 26643376

- Deimel GW Weroha JS Rodriguez-Porcel M 51-year-old hospitalized man with a painful leg Mayo Clin Proc 2011 86 3 241 244 21364115

- Yong TY Khow KSF Diabetic muscle infarction in end-stage renal disease: a scoping review on epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment World J Nephrol 2018 7 2 58 64 29527509

- Ergun T Lakadamyali H Diabetic muscle infarction: an unusual cause of acute calf pain Acta Clin Belg 2010 65 3 204 20669792

- Karalliedde J Vijayanathan S Thomas S Painful foot drop; a presentation of diabetic muscle infarction Diabet Med 2010 27 8 958 959 20653755

- Mimata Y Sato K Tokunaga K Tsukimura I Tada H Doita M Diabetic muscle infarction of the tibialis anterior and extensor Hallucis longus muscles mimicking the malignant soft-tissue tumor Case Rep Ortho 2015 2015 656307

- Horton WB Taylor JS Ragland TJ Subauste AR Diabetic muscle infarction: a systematic review BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2015 3 1 e000082

- Madhuvan HS Krishnamurthy A Prakash P Shariff S Diabetic muscle infarction (myonecrosis): underdiagnosed or underreported? J Assoc Physicians India 2015 63 4 71 73

- Jawahar A Balaji R Magnetic resonance imaging of diabetic muscle infarction: report of two cases Iowa Orthop J 2014 34 74 77 25328463

- Van Slyke MA Ostrov BE MRI evaluation of diabetic muscle infarction Magn Reson Imaging 1995 13 2 325 329 7739375

- Nuñez-Hoyo M Gardner CL Motta AO Ashmead JW Skeletal muscle infarction in diabetes: Mr findings J Comput Assist Tomogr 1993 17 6 986 988 8227592

- Heureux F Nisolle JF Delgrange E Donckier J Diabetic muscle infarction: a difficult diagnosis suggested by magnetic resonance imaging Diabet Med 1998 15 7 621 622 9686707

- Onyenemezu I Capitle E Retrospective analysis of treatment modalities in diabetic muscle infarction Open Access Rheumatol 2014 6 1 6 27790029

- Keller DR Erpelding M Grist T Diabetic muscular infarction. Preventing morbidity by avoiding excisional biopsy Arch Intern Med 1997 157 14 1611 9236564