Abstract

Very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) are an effective means by which to induce clinically significant weight loss. However, their acceptance by health care practitioners and the public is generally lower than that for other nonsurgical weight loss methods. Whilst there is currently little evidence to suggest they have any detrimental effect on hepatic and renal health, data assessing these factors remain limited. We carried out a systematic review of the literature on randomized controlled trials that had a VLCD component and that reported outcomes for hepatic and renal health, published between January 1980 and December 2012. Cochrane criteria were followed, and eight out of 196 potential articles met the inclusion criteria. A total of 548 participants were recruited across the eight studies. All eight studies reported significant weight loss following the VLCD. Changes in hepatic and renal outcomes were variable but generally led to either no change or improvements in either of these. Due to the heterogeneity in the quality and methodology of the studies included, the effect of VLCDs on hepatic and renal outcomes remains unclear at this stage. Further standardized research is therefore required to fully assess the impact of VLCDs on these outcome measures, to better guide clinical practice.

Keywords:

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing globally, and effective weight loss treatment is of great importance from both a health and socioeconomic perspective.Citation1 Very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) are an effective means by which to induce a clinically significant weight loss.Citation2 However, their acceptance by health care practitioners and the public, in general, is much lower than that for other nonsurgical weight loss methods. This is likely to be due to the adverse effects of the nutritionally insufficient VLCDs that were popular in the 1970s, which resulted in a number of deaths due to vitamin and mineral deficiencies and consumption of poor quality or inadequate amounts of protein.Citation3,Citation4 The VLCDs of the past were, however, completely different from the nutritionally replete variants of modern day VLCDs, and despite the fact that fast weight loss, seen in followers of a VLCD, is still generally perceived as being unsafe, there is no convincing evidence to suggest that this is the case. Indeed, the European Food Safety Authority has approved a health claim with regards to the efficacy of VLCDs on weight loss, in a target population of obese adults.Citation5

A VLCD is defined as a diet of <800 kcal/day,Citation6 and there are many commercially available variants that provide energy intakes between 300–800 kcal/day.

There is sufficient evidence in the literature to ensure the safe use of VLCDs in healthy overweight and obese patients in the short term;Citation7,Citation8 however, there remains limited evidence on the effects of VLCDs on specific disease groups over this same period of time. This is likely to, in part, be due to the strict protocols and monitoring that are advised with this type of dietary approach to weight loss. Although the evidence for the benefits of VLCDs is mounting in certain groups of individuals at higher cardiovascular risk, for example those with type 2 diabetes mellitus,Citation9,Citation10 there is little evidence of outcomes in patients with other obesity-related secondary diseases, such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). In a recent review, Mulholland et al,Citation2 investigating long-term (>12 months) randomized control trials of VLCD, identified only two reports of studies that evaluated effects on liver and kidney function.Citation11,Citation12 One paperCitation11 described that at 2 years follow up, there were no significant changes in liver transaminases. The other paperCitation12 reported both statistically and biologically significant improvements in both hepatic and renal health, including changes in alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, γ-Glutamyl transferase, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and urea. The observed changes in liver enzymes indicated an improvement in hepatic steatosis and an improvement in the biochemical markers associated with renal and hepatic pathology.

Furthermore, a recent study by Lim et alCitation13 reported that in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who followed a VLCD, the resulting acute negative energy balance reversed the type 2 diabetes mellitus by normalizing both insulin sensitivity and beta cell function. The authors suggested this result was due to the reduction of fat in the liver and pancreas. These results are in keeping with our previous findings, which demonstrated improvements in liver enzymes following a VLCD.Citation12

Whilst there is currently little evidence to suggest VLCDs cause any detriment to liver or kidney health, data assessing these factors remain limited. Thus, we aimed to carry out a systematic review of the literature and of studies investigating a VLCD and reporting outcomes for liver and kidney health, published between January 1980 and December 2012.

Methods

The protocol used for this systematic review follows the methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.Citation14 Further details of the approach are described below.

Inclusion criteria

This review was intended to assess the literature in this field. Studies from January 1980 to December 2012 were evaluated. Studies prior to 1980 were not included, due to health concerns associated with the formulations of the VLCDs in the 1970s.Citation3,Citation4 Only investigations of adult (18 years and over) participants with a mean or median body mass index (BMI) of ≥28 kg/m2 were included and only randomized controlled trials with a VLCD component were evaluated. Variations in the duration of the intervention which were aimed at achieving weight loss (ie, active weight loss prior to weight maintenance approaches) were recorded and accounted for, where possible.

Types of interventions

The focus of this review was to examine the effect of VLCDs on hepatic and renal outcomes. The types of dietary interventions evaluated were VLCDs (also known as very low-energy diets), defined as a dietary intake of 800 kcal/day or less.

Outcome measures

Weight loss was the main outcome assessed in the studies included in the review. With regard to hepatic or renal status, the following outcomes were also included:

Liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], alkaline phosphatase [ALKP], aspartate transaminase [AST], gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase [GGT], and albumin)

Electrolytes and markers of urea and kidney function (sodium, potassium, chloride, creatinine, and eGFR)

NAFLD.

Search strategy for the identification of included studies

This systematic review was restricted to studies where the full study report was available. A search strategy on MEDLINE was applied to identify as many as possible of the studies evaluating dietary interventions using VLCDs and relevant to hepatic and renal status. The search strategy incorporated the terms “very low calorie diet” and “very low energy diet.” Authors were contacted for further details of their trials and the reference lists of included studies and reviews were also searched.

Quality assessment of studies

The protocol used for the quality assessment followed the methods recommended by Avenell et al.Citation15 The studies were classified as having either a low risk of bias (A), an unclear risk of bias (B), or a high risk of bias (C). The subset “I” suggested that a description was provided while the subset “II” suggested that no description was provided.

Full copies of studies were assessed by two researchers, for methodological quality. The researchers were not blinded to the author, journal, or institution. Differences of opinion were resolved by discussion. The trial quality was assessed and included a consideration of whether or not the analysis was undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis.

Identified studies

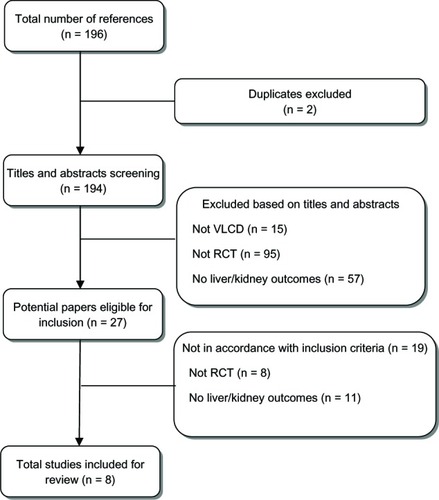

A total of eight out of 196 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. The reasons for the exclusion of studies are summarized in .

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 548 participants were recruited across the eight studies included in this systematic review. There was a large amount of heterogeneity in the study design for the papers meeting the inclusion criteria. The studies included ranged from 8 weeksCitation16 to 2 yearsCitation11 in duration. The duration of the VLCDs ranged from 25 daysCitation11 to 9 months.Citation12 In the follow-up phase, different studies incorporated aspects of behavior modification,Citation11 reduced calorie intake,Citation17–Citation19 or medication (acarbose) ().Citation20

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the review

All of the studies were designed to reduce weight or prevent weight gain and also examined hepatic and renal outcomes. The results of all the studies are summarized in .

Quality assessment

displays the quality assessment of the reported studies. All of the studies were randomized, but the allocation description was generally not provided, with the exception of one paper,Citation21 in which the method of concealment had a real chance of disclosure of assignment prior to formal trial entry. Four studiesCitation11,Citation18–Citation20 clearly stated the numbers and reasons for withdrawal from the study, while two studiesCitation12,Citation21 only provided the numbers of withdrawals, and two studiesCitation16,Citation17 made no mention of dropouts. Three studies analyzed the data with the intention to treat,Citation12,Citation20,Citation21 while threeCitation16,Citation17,Citation19 may also have done so, but the methods of analysis were unclear, and the final two studiesCitation11,Citation18 presented data for completers only. Participants as well as health care providers were blinded to the treatment in two studies (of a test emulsion,Citation18 and acarbose,Citation20 respectively); participants were not blinded in the other six studies, and it was unclear whether the health care providers or the outcome assessors were blinded to treatment status.

Table 2 Quality assessment of included RCTs

Weight change

All eight of the studies resulted in significant weight loss following the VLCD period (). Where weight change was reported after a follow-up period, the implementation of any of a reduced-calorie diet,Citation17 regular support through intensive or less intensive behavior modification therapy,Citation11 meal replacement once a day,Citation18 or ongoing use of VLCDCitation12 resulted in the maintenance of significant weight loss compared with baseline. Although no values for weight change were provided, Hauner et alCitation20 stated that the use of acarbose resulted in individuals remaining at a stable weight for the weeks following the VLCD ().

Hepatic outcomes

displays the results for different hepatic outcomes reported in three of the studies. Arai et alCitation16 observed an improvement in AST and ALT following the VLCD. Rolland et alCitation12 also reported an improvement in ALT as well as in ALKP, GGT, and albumin following the VLCD period. Melin et alCitation11 provided baseline values but only anecdotally reported (ie, no values were presented) that there were no changes in the liver transaminases.

Table 3 Summary of liver results

Two other studies reported anecdotal results of changes in hepatic outcomes. Olsson et alCitation18 reported that ALT levels increased significantly during the weight-reduction phase but were normalized during the 12-week weight maintenance phase, whereas Hauner et alCitation20 reported that no changes were observed in the serum transaminases in participants undergoing a VLCD followed by the use of acarbose.

Only one study investigated the effect of VLCDs on NAFLD. In the study by Lin et al,Citation21 41 participants with NAFLD were placed on a 450 kcal/day VLCD for 12 weeks. In this group, a 41.5% improvement rate in NAFLD was reported, where five of the 41 participants no longer had NAFLD, and others had improvements in severity; however, of the five participants in this group who did not have NAFLD at the beginning of the intervention, two had developed NAFLD by the end of the intervention. Lin et alCitation21 also had participants on an 800 kcal/d VLCD. In this latter group, they observed a 50% improvement rate, where of the 42 participants who initially presented with NAFLD, ten no longer had NAFLD, and of the five participants who did not have NAFLD at baseline, none developed it.

Renal outcomes

displays the results of the renal outcomes from the only paperCitation12 that provided values for changes in renal function. The results demonstrated an improvement in creatinine, urea, and eGFR levels in response to a VLCD.

Table 4 Results of kidney (renal) results

Two other studies reported anecdotal outcomes for renal function. Doherty et alCitation17 reported that there were no significant changes in potassium, sodium, or chloride observed at 45 weeks in response to a VLCD followed by a balanced deficit diet. Similarly, Ryttig and RössnerCitation19 reported that there were no significant changes in serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium) at the end of the 12 weeks of VLCD or during the weight maintenance period, between the two groups (balanced hypocaloric diet with or without a meal replacement component).

Discussion

As expected from previous studies, the VLCD interventions resulted in significant weight loss. The changes in hepatic and renal outcomes resulting from the weight loss achieved using the VLCDs were variable, but generally, there was either no change or an improvement in hepatic and renal health. This may be due to the fact that these studies measuring kidney and liver outcomes only included adults with normal kidney and liver function, with the exception of NAFLD.

The outcomes in terms of hepatic function were improved in some studies, remained the same in others, and initially increased during the VLCD phase but normalized thereafter in one study. The inconsistencies between these studies are likely to be due to a combination of things, including the different lengths of treatment, different sampling times, as well as different weight maintenance approaches. However, these studies certainly did not demonstrate any negative outcomes for hepatic health in response to a VLCD and subsequent follow up. On the contrary, when looking at the outcomes for NAFLD, the effect of the weight loss achieved by the VLCD resulted in important improvements in NAFLD, most likely due to the associated decrease in visceral adiposity.Citation22 These results are supported by our earlier findingsCitation12 and suggestion that changes in liver enzymes may indicate an improvement in hepatic steatosis. Several other studies have also suggested beneficial effects of weight loss on liver size and adiposity. Colles et alCitation23 observed that during a 12-week VLCD, most of the reduction in liver size occurred in the first 2 weeks of weight loss, likely due to the depletion of liver glycogen and bound water (caused by the low carbohydrate content of the diet).Citation24 Favorable changes were also observed in a range of biochemical and clinical tests (significant decreases in ALKP, bilirubin, ALT, and GGT). Andersen et alCitation25 investigated the effects of weight loss induced by a VLCD on liver morphology and function in morbidly obese but otherwise healthy individuals. They observed a marked improvement in hepatic health, which correlated with the reduction of weight. However, they also observed that 24% of the patients developed a slight portal inflammation as well as, in 12% of patients, a slight portal fibrosis. They did not find predictors (morphological or biochemical) for these changes and hypothesized that a fast mobilization of intracellular triacylglycerols and subsequent secretion of fatty acids had induced a portal inflammation, which in turn, led to the fibrosis. They proposed that a rapid mobilization of intra- and extrahepatic fat stores may present a hepatotoxic factor common to all weight loss treatments that induce rapid weight loss. Based on their observations, they postulated that to avoid the development of portal fibrosis during treatment with VLCD, a weight loss slower than 1.6 kg/week should be recommended.

The issue of the development of fibrosis in the study by Andersen et alCitation25 should not be confused with the development of fibrosis observed in individuals following bariatric surgery, another approach that induces rapid weight loss. Several studies have reported improvements in liver biochemical and histological outcomes following bariatric surgery,Citation26–Citation28 but some authors have expressed concern that rapid weight loss may be a causative factor in the occurrence of fibrosis that was observed.Citation27–Citation29 However, as Kral et alCitation28 suggest, this may be due to a decreased serum albumin and poorly managed diarrhea, which are two known potential side effects of certain types of bariatric surgery. The problems with hepatic fibrosis are well knownCitation30 and are probably not related to the rate of weight loss but rather, to surgically induced short bowel syndrome. Certainly, the issue of fibrosis did not figure in the clinical trials highlighted in this systematic review, and such situations are not generally associated with the use of low-calorie diet or VLCD interventions.

Limited information was available regarding the response of renal function to the weight loss induced by VLCD. Nevertheless, the current data suggest either an improvement or no change in response to weight loss induced by a VLCD followed by a weight maintenance period. Previously, we suggested that improvements in renal function during a VLCD are possible, due to the associated increase in fluid intake and/or reduction in creatine intake.Citation12

Obesity-related glomerular disease was first identified by Weisinger et alCitation31 in the 1970s, and the prevalence of obesity-related glomerulopathy has been increasing as a consequence of the obesity epidemic.Citation32 It has been suggested that reducing the glomerular hyperfiltration observed in the obese may provide a way to prevent or delay the development of renal disease in these individuals.Citation33 Indeed, Chagnac et alCitation33 demonstrated improvements in GFR following weight loss induced by a gastroplasty. This finding is supported by the review by Navaneethan et al,Citation34 in which the researchers reported that in patients with chronic kidney disease, bariatric surgery was associated with a decrease in BMI, with resultant normalization of glomerular hyperfiltration; however, they also stated that it remains to be clarified whether this normalization can result in long-term renal benefits. Previously, we reported an improvement in eGFR following the VLCD.Citation12 The use of eGFR, however, is a poor indicator of improved renal function in this case – as a direct result of the use of VLCDs, the intake of creatine drops dramatically, and hence, the serum creatinine also drops, and this may give a false impression of improved renal function. Also, the use of eGFR significantly underestimates measured kidney function with obesity, and measuring changes in eGFR when body surface area is also changing is problematic.Citation35

In addition, the use of eGFR has not been validated in patients with normal kidney function.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation of this review is the small number of studies included as well as the lack of data presented in many of the studies. In addition, the heterogeneity of the studies in terms of study quality, treatment duration, outcomes measured, and time points rendered it impossible to carry out a meta-analysis. It is also important to highlight that only one studyCitation16 reported hepatic outcomes, and none reported renal outcomes immediately post-VLCD (or during active VLCD) compared with follow up (long after the VLCD was completed).

Finally, in assessing kidney function outcomes, it would have been beneficial to have information about renal blood flow, arterial pressure, and albuminuria.

Conclusion

There are currently no effective treatments for NAFLD other than weight reduction and lifestyle modification.Citation36,Citation37 The effect of VLCDs on hepatic and renal outcomes remains unclear at this stage. There have been a number of improvements observed in terms of hepatic and renal outcomes; however, there may be some concern about the onset of fibrosis in some individuals, although no evidence for this was observed in the current systematic review. Renal outcomes seem little affected by VLCDs; however, the studies measuring kidney function included only adults with normal kidney function, and the results cannot be extrapolated to those with any degree of kidney dysfunction. At this stage, further standardized research is required to fully assess the impact of VLCDs on hepatic and renal health and to better advise clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by LighterLife Ltd, UK.

Disclosure

CR has received lecture honoraria and has attended national/international meetings as a guest of LighterLife Ltd, UK. CR and JB have been involved with other companies with an interest in obesity. JB and KLJ are employed by LighterLife Ltd, UK. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang YC McPherson K Marsh T Gortmaker SL Brown M Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK Lancet 2011 378 9793 815 825 21872750

- Mulholland Y Nicokavoura E Broom J Rolland C Very-low-energy diets and morbidity: a systematic review of longer-term evidence Br J Nutr 2012 108 5 832 851 22800763

- van Itallie TB Liquid protein mayhem JAMA 1978 240 2 144 660833

- Centers For Disease Control Liquid Protein Diets. Public Health Service Report Atlanta, GA Centers For Disease Control 1979

- European Food Safety Authority Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to very low calorie diets (VLCDs) and reduction in body weight (ID 1410), reduction in the sense of hunger (ID 1411), reduction in body fat mass while maintaining lean body mass (ID 1412), reduction of post-prandial glycaemic responses (ID 1414), and maintenance of normal blood lipid profile (1421) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 EFSA Journal 2011 9 6 2271 2293

- Atkinson RL Dietz WH Foreyt JP National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity, National Institutes of Health Very low-calorie diets JAMA 1993 270 8 967 974 8345648

- Capstick F Brooks BA Burns CM Zilkens RR Steinbeck KS Yue DK Very low calorie diet (VLCD): a useful alternative in the treatment of the obese NIDDM patient Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1997 36 2 105 111 9229194

- Williams KV Mullen ML Kelley DE Wing RR The effect of short periods of caloric restriction on weight loss and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes Diabetes Care 1998 21 1 2 8 9538962

- Dhindsa P Scott AR Donnelly R Metabolic and cardiovascular effects of very-low-calorie diet therapy in obese patients with Type 2 diabetes in secondary failure: outcomes after 1 year Diabet Med 2003 20 4 319 324 12675647

- Jazet IM de Craen AJ van Schie EM Meinders AE Sustained beneficial metabolic effects 18 months after a 30-day very low calorie diet in severely obese, insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007 77 1 70 76 17134786

- Melin I Karlström B Lappalainen R Berglund L Mohsen R Vessby B A programme of behaviour modification and nutrition counselling in the treatment of obesity: a randomised 2-y clinical trial Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003 27 9 1127 1135 12917721

- Rolland C Hession M Murray S Wise A Broom I Randomized clinical trial of standard dietary treatment versus a low-carbohydrate/high-protein diet or the LighterLife Programme in the management of obesity* J Diabetes 2009 1 3 207 217 20923540

- Lim EL Hollingsworth KG Aribisala BS Chen MJ Mathers JC Taylor R Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol Diabetologia 2011 54 10 2506 2514 21656330

- Clarke M Oxman AD Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook 415 In The Cochrane Library Oxford Update Software 2002

- Avenell A Broom J Brown TJ Systematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvement Health Technol Assess 2004 8 21 iii iv 1 15147610

- Arai K Miura J Ohno M Yokoyama J Ikeda Y Comparison of clinical usefulness of very-low-calorie diet and supplemental low-calorie diet Am J Clin Nutr 1992 56 Suppl 1 S275 S276

- Doherty JU Wadden TA Zuk L Letizia KA Foster GD Day SC Long-term evaluation of cardiac function in obese patients treated with a very-low-calorie diet: a controlled clinical study of patients without underlying cardiac disease Am J Clin Nutr 1991 53 4 854 858 2008863

- Olsson J Sundberg B Viberg A Haenni A Effect of a vegetable-oil emulsion on body composition; a 12-week study in overweight women on a meal replacement therapy after an initial weight loss: a randomized controlled trial Eur J Nutr 2011 50 4 235 242 20820791

- Ryttig KR Rössner S Weight maintenance after a very low calorie diet (VLCD) weight reduction period and the effects of VLCD supplementation. A prospective, randomized, comparative, controlled long-term trial J Intern Med 1995 238 4 299 306 7595165

- Hauner H Petzinna D Sommerauer B Toplak H Effect of acarbose on weight maintenance after dietary weight loss in obese subjects Diabetes Obes Metab 2001 3 6 423 427 11903414

- Lin WY Wu CH Chu NF Chang CJ Efficacy and safety of very-low-calorie diet in Taiwanese: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial Nutrition 2009 25 11–12 1129 1136 19592223

- Vilar L Oliveira CP Faintuch J High-fat diet: a trigger of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis? Preliminary findings in obese subjects Nutrition 2008 24 11–12 1097 1102 18640006

- Colles SL Dixon JB Marks P Strauss BJ O’Brien PE Preoperative weight loss with a very-low-energy diet: quantitation of changes in liver and abdominal fat by serial imaging Am J Clin Nutr 2006 84 2 304 311 16895876

- Olsson KE Saltin B Variation in total body water with muscle glycogen changes in man Acta Physiol Scand 1970 80 1 11 18 5475323

- Andersen T Gluud C Franzmann MB Christoffersen P Hepatic effects of dietary weight loss in morbidly obese subjects J Hepatol 1991 12 2 224 229 2051001

- Bhathal PS Dixon JB Hughes NR O’Brien PE Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss Hepatology 2004 39 6 1647 1654 15185306

- Mattar SG Velcu LM Rabinovitz M Surgically-induced weight loss significantly improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome Ann Surg 2005 242 4 610 620 16192822

- Kral JG Thung SW Biron S Effects of surgical treatment of the metabolic syndrome on liver fibrosis and cirrhosis Surgery 2004 135 1 48 58 14694300

- Luyckx FH Desaive C Thiry A Liver abnormalities in severely obese subjects: effect of drastic weight loss after gastroplasty Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998 22 3 222 226 9539189

- Friedman SL The cellular basis of hepatic fibrosis. Mechanisms and treatment strategies N Engl J Med 1993 328 25 1828 1835 8502273

- Weisinger JR Kempson RL Eldridge FL Swenson RS The nephrotic syndrome: a complication of massive obesity Ann Intern Med 1974 81 4 440 447 4416380

- Mokdad AH Serdula MK Dietz WH Bowman BA Marks JS Koplan JP The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998 JAMA 1999 282 16 1519 1522 10546690

- Chagnac A Weinstein T Herman M Hirsh J Gafter U Ori Y The effects of weight loss on renal function in patients with severe obesity J Am Soc Nephrol 2003 14 6 1480 1486 12761248

- Navaneethan SD Yehnert H Moustarah F Schreiber MJ Schauer PR Beddhu S Weight loss interventions in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009 4 10 1565 1574 19808241

- Delanaye P Radermecker RP Rorive M Depas G Krzesinski JM Indexing glomerular filtration rate for body surface area in obese patients is misleading: concept and example Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005 20 10 2024 2028 16030047

- Suzuki A Lindor K St Saver J Effect of changes on body weight and lifestyle in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease J Hepatol 2005 43 6 1060 1066 16140415

- Clark JM Weight loss as a treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease J Clin Gastroenterol 2006 40 Suppl 1 S39 S43 16540766