Abstract

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) affects between 2% and 26% of reproductive-age women in the UK, and accounts for up to 75% of anovulatory infertility. The major symptoms include ovarian disruption, hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and polycystic ovaries. Interestingly, at least half of the women with PCOS are obese, with the excess weight playing a pathogenic role in the development and progress of the syndrome. The first-line treatment option for overweight/obese women with PCOS is diet and lifestyle interventions; however, optimal dietary guidelines are missing. Although many different dietary approaches have been investigated, data on the effectiveness of very low-calorie diets on PCOS are very limited.

Materials and methods

The aim of this paper was to investigate how overweight/obese women with PCOS responded to LighterLife Total, a commercial very low-calorie diet, in conjunction with group behavioral change sessions when compared to women without PCOS (non-PCOS).

Results

PCOS (n=508) and non-PCOS (n=508) participants were matched for age (age ±1 unit) and body mass index (body mass index ±1 unit). A 12-week completers analysis showed that the total weight loss did not differ significantly between PCOS (n=137) and non-PCOS participants (n=137) (−18.5±6.6 kg vs −19.4±5.7 kg, P=0.190). Similarly, the percentage of weight loss achieved by both groups was not significantly different (PCOS 17.1%±5.6% vs non-PCOS 18.2%±4.4%, P=0.08).

Conclusion

Overall, LighterLife Total could be an effective weight-loss strategy in overweight/obese women with PCOS. However, further investigations are needed to achieve a thorough way of understanding the physiology of weight loss in PCOS.

Keywords:

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common female endocrine disorders, affecting 2%–26% of women of reproductive age (12–45 years old) in the UK,Citation1–Citation3 and is suggested to be responsible for up to 75% of cases of infertility caused by anovulation.Citation4 While the exact etiology and pathophysiology of PCOS is complicated, the resultant hormonal imbalance due to both elevated androgen levels and increased insulin secretion in combination with environmental (eg, lifestyle) and genetic factors collectively contribute to the etiology of this syndrome.Citation5,Citation6 PCOS has been associated with a variety of reproductive and skin disorders and also with an adverse metabolic profile including systemic dysfunctions, such as insulin resistance with compensatory hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.Citation7,Citation8

Many studies have reported that there may be a genetic susceptibility to the development of PCOS. For example, Franks et alCitation9 reported that a genetic polymorphism may be responsible for the upregulated insulin metabolism among PCOS patients. Moreover, between 50% and 87% of first-degree relatives of women with PCOS will present with some symptoms to varying degrees,Citation10 including but not limited to hypertriglyceridemia, hyperinsulinemia, and type 2 diabetes.Citation11

Increased weight, and central obesity in particular, play an important role in the development of PCOS, and as such the majority of women with this syndrome are either overweight or obese.Citation12–Citation14 Although the exact pathophysiological interactions between excess weight and the clinical expression of PCOS remain to be elucidated, it is generally acknowledged that obesity itself is an independent risk factor associated with disturbances in sex-steroid metabolism,Citation15 insulin resistance,Citation10 and menstrual irregularities.Citation16 Obesity in PCOS, however, exacerbates the reproductive, metabolic, and psychological effects of excessive weight, and thus optimal weight-loss guidelines in the management of PCOS are of crucial importance.

Obese women with PCOS face additional barriers in achieving weight loss when compared to healthy women without this condition. This is postulated to be due to either the observed decrease in postprandial thermogenesis,Citation17 which is also correlated with the degree of reduced insulin sensitivity,Citation18 or to specific eating behaviors (eg, emotional eating) and snacking patterns (cravings for high-caloric sweet and savory snacks) that are observed among overweight/obese women with PCOS.Citation19 The first-line treatment for PCOS includes diet and lifestyle interventionsCitation20 to promote a healthy weight, especially in cases of overweight and obese patients. In these cases, even a modest weight loss of 2%–5% total body weight may restore ovulation,Citation21–Citation25 improve the reproductive hormonal profile,Citation24–Citation28 and achieve an improvement in insulin sensitivity.Citation23,Citation26–Citation29

There is still, however, much debate over what is considered to be the optimal weight-loss strategy in PCOS, resulting in a lack of evidence-based advice given by dietitians.Citation30 Interestingly, Jeanes et alCitation31 investigated the dietary recommendations for PCOS patients given by UK dietitians, and found little difference from that given to non-PCOS subjects, despite the known difficulty among PCOS patients to lose weight.

In a systematic review by Nicholson et al,Citation32 the efficacy of long-term (≥12 months) nonsurgical weight-loss interventions were presented, and behavioral strategies for obese women with PCOS in a systematic review were identified. It was concluded that there was not enough evidence to suggest an ideal weight-loss approach in patients with PCOS. Although many different dietary approaches have been investigated, data on the effectiveness of very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) on PCOS are still limited.

A VLCD can be defined as a nutrition plan that provides ≤800 kcal per day,Citation33 and it is comprised of either conventional meals or synthetic formulas, eg, shakes, soups, or bars, or a combination of both. However, it has been also mentioned by Mulholland et al,Citation34 modern VLCDs should not be confused with the ones used in the 1970s, the latter being associated with several deaths, mainly due to the inclusion of poor-quality protein and the inadequate provision of vitamins and minerals.Citation35,Citation36 Modern commercial VLCDs take into consideration the maintenance of lean body mass by fortification of the formulae with high levels of good-quality protein and the inclusion of essential electrolytes (sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, chloride, calcium, phosphates), fatty acids, minerals, and vitamins.Citation37 This approach is safe, and according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,Citation38 it can be used for up to 3 months continuously for obese patients who fail to meet their weight-loss target using a standard low-fat, calorie-deficient diet (CDD).

A VLCD can lead to an average weekly weight loss of 1.5–2.5 kg vs the 0.4–0.5 kg loss achieved with the CDDs.Citation33 Moreover, the average weight loss at 12 weeks for an obese individual is approximately 20 kg on a VLCD, whereas it is only 8 kg on a CCD.Citation33 Consequently, a VLCD could be a good alternative for obese PCOS patients – both in the short and longer term – who may face difficulties losing weight despite following standard approaches. For example, Tolino et alCitation25 showed that weight loss achieved after 4 weeks of a VLCD may lead to a decrease of free testosterone and fasting insulin levels and induce further improvement in menstruation. Van Dam et alCitation39 carried out an interesting study to investigate the effect of short-term dieting in luteinizing hormone (LH) homeostasis in obese patients with PCOS. According to the observations, both basal and pulsatile secretion of LH were three times higher in PCOS patients when compared to matched individual without PCOS, implying that caloric restriction failed to normalize the LH secretion. On the contrary, total testosterone, glucose, and insulin levels were decreased. In another study, the same researchersCitation40 examined 15 obese participants with PCOS. Patients were studied at baseline (occasion 1), after 1 week of a VLCD (occasion 2), and then after achieving 10% weight loss via a VLCD (occasion 3). Results suggested that after the weight loss achieved, the estradiol-dependent negative feedback on LH was normalized and led to resumption of ovulation.

Overall, although there is evidence supporting the efficacy of VLCDs, for obese patients who fail to meet their weight-loss target using a standard CDD, this approach has not been adequately investigated in the area of PCOS, and both short- and longer-term data are still needed.

The aim of this retrospective analysis was to assess the change in weight in individuals with and without PCOS during a 12-week course of a commercial VLCD complemented by a group-based behavior-change program (LighterLife Total).

Materials and methods

Source of data

For this retrospective analysis, data were included from women aged 18–75 years with body mass index (BMI) ≥28 kg/m2 who followed the LighterLife Total approach from January 2006 until December 2011. Ethical permission for this analysis was obtained from the Robert Gordon University Ethics Committee.

Study population

Study participants were self-referred onto the VLCD program. Prior to commencement of their weight loss, their health and fitness to undertake the weight-loss program was assessed using a standardized form provided by LighterLife. Participants were excluded from taking part in the LighterLife Total program, and consequently from the study as well, if they met any of the following criteria: type 1 diabetes; porphyria; total lactose intolerance; major cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease; history of renal disorder or hepatic disease; active cancer; epilepsy, seizures, convulsions, major depressive disorder, psychotic episodes, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, or delusional disorders; current suffering from anorexia, bulimia, or undergoing treatment for any other eating disorder; pregnant or breastfeeding; had given birth or had a miscarriage in the last 3 months.

From a total sample of 102,610 LighterLife participants, the PCOS participants (n=508) were matched for age (age ±1 unit) and BMI (BMI ±1 unit) with the non-PCOS participants (n=508) for analysis of 12-week weight-loss data. Baseline demographics and 12-week changes in weight and blood pressure were compared for the two groups.

Weight-loss program

For those individuals who were eligible, the intervention was carried out within a community-based setting. Appointments and treatments were managed by lay (but trained behavior-change) facilitators. The intervention used was a commercial weight-management program (LighterLife Total). This is a tripartite approach for individuals with BMI $30 kg/m2, comprising a VLCD and group support along with behavior therapy. The program aims to achieve weight loss and to identify personal psychological motivation for overconsumption, thereby enabling participants to develop robust strategies for more successful weight management in the future.

Diet and nutrition

The VLCD provides an average daily intake of 600 kcal (50 g protein, 50 g carbohydrate, mean 17 g fat, ie, 36% energy from protein, 36% carbohydrate, and 28% fat) in the form of food packs (soups, shakes, textured meals, and bars) that contain ≥100% recommended daily allowances for vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A, C, D, E, K, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, B6, B12, folic acid, biotin, pantothenic acid, calcium, phosphorous, iron, zinc, magnesium, iodine, potassium, sodium, copper, manganese, selenium, molybdenum, chromium, chloride, and fluoride. Clients were also able to purchase an ancillary “fiber mix” to add to their water, which contained inulin as the source of fiber.

Participants undertook the VLCD alongside a unique behavior-change program developed specifically for weight management in the obese. This is informed by concepts from cognitive behavioral therapy and transactional analysis (transactional cognitive behavioral therapy) and addiction/change theory.Citation41–Citation43 It is delivered in small, single-sex, weekly groups by weight-management counselors who are specifically trained in the facilitation of behavior change for the treatment of obesity.

Measurements

Measurements of height and weight took place in LighterLife centers, and were carried out by facilitators who had been trained and provided with protocols developed within LighterLife. The actual types of equipment used for these measurements were not recorded. Measurements were taken during weekly meetings that occurred at the same location and time each week.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of the individual parameters was performed by the use of descriptive statistics, and all variables were assessed for normality. Differences of continuous variables between groups were assessed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test, and differences within groups were assessed using a paired t-test. If more than two groups were compared, analysis of variance with a Bonferroni post hoc test was used. For categorical outcomes, a χ2 analysis was used. All P-values were two-sided, and a P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Power

The sample size (508 per group) for this retrospective analysis provided a power greater than 88% to detect a minimum difference of 0.2 kg in weight change between the PCOS and non-PCOS groups.

Results

The 12-week analysis included both a baseline observation carried forward (BOCF) (n=508 for PCOS and n=508 for non-PCOS) and a completers (n=137 for PCOS and n=137 for non-PCOS) analysis.

BOCF analysis

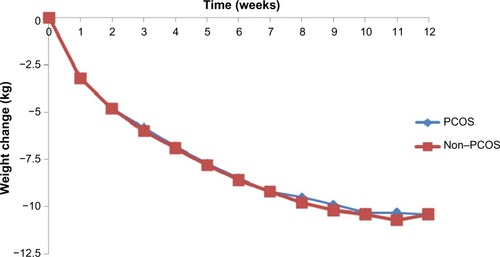

There were no differences between the PCOS and non-PCOS women in age (34.5±8.2 vs 34.5±8.2 years, P=0.948), height (1.65±0.1 m vs 1.65±0.1 m, P=0.937), weight (105.4±18.9 kg vs 105.3±19.0 kg, P=0.892), and BMI (38.9±6.4 kg/m2 vs 38.8±6.4 kg/m2, P=0.831), as they were all matched at baseline. Weekly weight loss was similar for both groups, with no statistically significant differences ().

Figure 1 Weekly weight change for participants with and without PCOS (12-week BOCF, n=508 for each group).

After 12 weeks of the VLCD, there was a significant weight reduction within each group when compared to baseline PCOS (105.4±18.9 kg vs 95.0±19.1 kg, P<0.001) and non-PCOS (105.3±19.0 kg vs 94.9±19.5 kg, P<0.001). There was also a significant change in BMI compared to baseline PCOS (38.9±6.4 kg/m2 vs 35.0±6.6 kg/m2, P<0.001) and non-PCOS: (38.8±6.4 kg/m2 vs 35.0±6.8 kg/m2, P<0.001). Total weight change did not differ significantly between the PCOS group and the non-PCOS group (−10.4±10.6 vs −10.4±10.4 kg, P=0.938), and both of the groups achieved approximately 10% weight loss after the 12-week VLCD approach (PCOS −9.7%±9.4% vs non-PCOS −9.7%±9.7%, P=0.965).

shows the changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure between the PCOS and non-PCOS groups after the 12-week VLCD period. As can be seen from the table, although the baseline systolic blood pressure was similar for both PCOS and non-PCOS participants (PCOS 127.4±12.5 mmHg vs non-PCOS 127.0±14.0 mmHg, P=0.598), the reduction observed after 12 weeks of VLCD was greater in the PCOS group (PCOS −5.5±6.1 mmHg vs non-PCOS −0.9±6.1 mmHg, P<0.001). With regard to diastolic blood pressure, although at baseline women with PCOS had greater values than non-PCOS (PCOS 81.5±10.2 mmHg vs non-PCOS 79.9±9.7 mmHg, P=0.014), after 12 weeks of VLCD both groups had similar values (PCOS 80.8±16.1 mmHg vs non-PCOS 79.4±9.9 mmHg, P=0.206).

Table 1 Comparison of systolic and diastolic blood pressure between the PCOS and non-PCOS participants at baseline and 12 weeks

Completers analysis

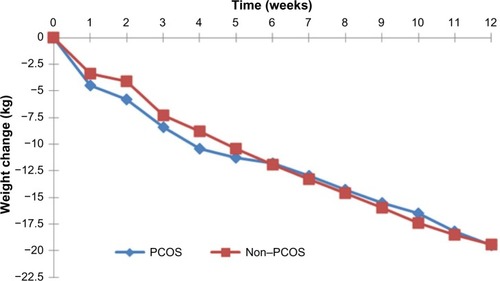

As can be seen in , there were no differences between the PCOS and non-PCOS women in age (35.7±8.9 years vs 35.8±8.9 years, P=0.946), height (1.65±0.1 m vs 1.64±0.1 m, P=0.212), weight (108.3±18.1 kg vs 107.4±19.8 kg, P=0.713), or BMI (40.0±6.3 kg/m2 vs 40.0±6.3 kg/m2, P=0.955). Weekly weight loss was similar for both groups, with no significant statistical differences ().

Table 2 Comparison of baseline characteristics between PCOS (n=137) and matched non-PCOS (n=137)

Figure 2 Weekly weight change for participants with and without PCOS (12-week completers, n=137 for each group).

After 12 weeks of the VLCD, there was a significant weight reduction within both groups when compared to baseline PCOS (108.3±18.1 kg vs 89.8±16.7 kg, P<0.001) and non-PCOS (107.4±19.8 kg vs 88.0±17.6 kg, P<0.001). There was also a significant change in BMI compared to baseline PCOS (40.0±6.4 kg/m2 vs 33.2±6.0 kg/m2, P<0.001) and non-PCOS (40.0±6.3 kg/m2 vs 32.8±5.7 kg/m2, P<0.001). Total weight change did not differ significantly between the PCOS group and the non-PCOS group (−18.5±6.6 kg vs −19.4±5.7 kg, P=0.190), and the percentage of weight loss achieved by PCOS women was 17.1%±5.6% vs 18.2%±4.4% by the non-PCOS group (P=0.08). Moreover, no significant differences in weekly weight change between the two groups were identified ().

shows the blood pressure values at baseline and after 12 weeks of VLCD. As can be seen from the table, baseline systolic blood pressure was lower for the PCOS group compared to the non-PCOS group (PCOS 127.2±12.4 mmHg vs non-PCOS 130.5±13.9 mmHg, P=0.014); however, there were no differences after 12 weeks of the VLCD (PCOS 119.1±13.6 mmHg vs non-PCOS 119.4±13.8 mmHg, P=0.800). With regard to diastolic blood pressure, it was similar for the PCOS and non-PCOS groups, both at baseline (PCOS 81.3±9.8 mmHg vs non-PCOS 80.5±9.6 mmHg, P=0.598) and after 12 weeks of the VLCD (PCOS 77.5±11.6 mmHg vs non-PCOS 74.9±10.2 mmHg, P=0.237).

Table 3 Values for blood pressure and pulse between the PCOS and non-PCOS groups at baseline and 12 weeks

Discussion

One of the biggest health problems globally is the increasing prevalence of obesity. According to the National Infertility Group Report,Citation44 half of the women of reproductive age are either overweight or obese, and it is known that increased weight, and in particular central obesity, plays an important role in the development of PCOS.Citation13 Although the first-line treatment in overweight and obese women with PCOS is weight loss through lifestyle interventions, the complexity and heterogeneity of this syndrome in conjunction with the lack of robust large scale randomized clinical trials lead to lack of consensus over the optimal dietary guidelines to achieve that goal.

In this paper, we attempted to investigate the effect of the LighterLife Total VLCD program on weight loss in overweight and obese women with PCOS compared to age-and BMI-matched non-PCOS participants. It is generally proposed that as little as 5% weight loss can improve fertility outcomes.Citation21–Citation28 In this study, PCOS (completers) achieved similar weight reduction with the non-PCOS (completers) group, which was more than three times higher than the minimum suggested weight loss: 17.1%±5.6% by the PCOS vs 18.2%±4.4% by the non-PCOS group (P=0.08) after 12 weeks of VLCD in conjunction with group counseling. The BOCF analysis showed more conservative results (PCOS −9.7%±9.4% vs non-PCOS −9.7%±9.7%, P=0.965), although nevertheless promising. Moreover, in both completers and BOCF analysis, women with PCOS lost weight at the same rate as non-PCOS women. This is in contrast with a number of papers which mentioned that women with PCOS may face difficulties in achieving weight loss either due to consequent metabolic issuesCitation18,Citation19,Citation44 or the emotional distress that accompanies this disorder, and predisposes towards increased energy consumption. For example, it has been suggested that women with PCOS may have reduced postprandial thermogenesis associated with reduced insulin sensitivity, a factor that could influence the weight loss.Citation18 In addition, adjusted basal metabolic rate appears to be statistically significantly lower in women with PCOS, and is more evident in women with both PCOS and insulin resistance.Citation45 Interestingly, similar observations have been made with regard to patients with type 2 diabetes.Citation46 Moreover, PCOS patients very often have deranged appetite regulation due to reduced postprandial cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion compared to control age-and BMI-matched individuals without PCOS.Citation47 However, in cases where weight reduction was achieved via a ketogenic diet, the levels of CCK maintained similar concentrations with the ones before the weight loss.Citation48 This could suggest that due to the anorexogenic effect of ketosis, the levels of CCK were normalised among the PCOS patients, thus similar weight loss was achieved between the PCOS and non-PCOS group, as also shown by our analysis.

While improvements in weight and BMI have been reported by other researchers using variable dietary approaches, these lacked a control group,Citation24,Citation49,Citation50 whereas in the present study, women without PCOS acted as the control group and were also matched for age and BMI for further analysis. Moreover, this is the only study in the area of PCOS and VLCDs that incorporated the counseling component. Although the effect of counseling per se was not assessed, it is known that the element of behavioral change not only can enhance weight loss but may also improve the completion rates of weight-loss programs.Citation51 This support is of extreme importance among PCOS patients, where higher incidences of depressive and anxiety disorders may predispose them toward unhealthy eating behaviors.

Furthermore, several studies have suggested that there is an increased prevalence of hypertension among women with PCOS compared to the general population, irrespective of their weight.Citation52–Citation54 On the other hand, Luque-Ramírez et alCitation55 support the view that high blood pressure is only observed among overweight and obese women with PCOS. In our study, women with PCOS presented with higher diastolic pressure at baseline, but after 12 weeks of the VLCD, both systolic and diastolic pressure were at similar levels with their non-PCOS counterparts. This interesting finding could imply that in cases of obese women with PCOS, weight loss could contribute to normalization of blood pressure levels. Nevertheless, further research needs to be done, including 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring as well as assessment of medication intake and hormonal profile, both at baseline and after the end of the VLCD program.

The main strength of the current study is that this is the largest investigation to date of a commercial VLCD program, LighterLife Total, on weight loss in overweight/obese women with PCOS compared to overweight/obese women without this syndrome. Although the gold standard in evaluating health care interventions is carefully designed, conducted, and reported randomized controlled trials, our population-based retrospective analysis assessed the effectiveness of a commercial VLCD program in conjunction with weekly counseling group sessions, as it runs for real clients who joined the LighterLife Total program.

The limitations encountered are mainly attributed to the retrospective design of this research. For example, there was no information on the criteria used for diagnosis of PCOS, and it is highly possible that each of the PCOS women had been diagnosed by a different doctor. However, Rolland et alCitation46 reported that there was no difference in weight loss between diabetes and nondiabetes participants when they followed the LighterLife Total program, despite the lack of discrepancy in relation to diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Another potential bias could be financial status, as only women who can afford the weekly costs of this commercial program (approximately £65 per week) were included. Moreover, due to the small numbers encountered in some of the ethnic groups, comparisons between the different ethnic categories encountered could not be performed. In addition, information on medication or potential changes in insulin sensitivity, glycemia, and reproductive phenotype was not assessed.

Conclusion

PCOS is a complex condition, with diverse implications that include reproductive, metabolic, and psychological comorbidities. Its clinical management should focus on lifestyle changes with medical therapy when required, as well as providing patients with support and nutritional education. However, evidence-based guidelines are still needed to guide clinicians and patients in optimal dietary management of this syndrome. The present retrospective analysis suggests that women with PCOS lose the same amount of weight and at the same rate as non-PCOS women after following a commercial VLCD program for 12 weeks in conjunction with group-counseling sessions. Consequently, this approach could be considered an effective alternative to standard LCDs, especially in cases where difficulties in achieving weight loss are encountered.

Author contributions

CR and JB designed the study. Data were collected by EAN. Data analysis and writing of the manuscript were carried out by EAN and CR. CR, EAN, JB, WLW, and KLJ interpreted the data and commented on drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by LighterLife Ltd, UK. Some of the data were published in abstract form and presented at ECO 2013.

Disclosure

CR has received lecture honoraria and has attended national/international meetings as a guest of LighterLife UK. EAN has received funding and has attended national/international meetings as a guest of LighterLife UK. CR, JB, and WLW have been involved with other companies with an interest in obesity. KLJ is employed by LighterLife UK. JB was an adviser to LighterLife UK.

References

- MichelmoreKFBalenAHDungerDBVesseyMPPolycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young womenClin Endocrinol (Oxf)1999516779 78610619984

- HopkinsonZESattarNFlemingRGreerIAPolycystic ovarian syndrome: the metabolic syndrome comes to gynaecologyBMJ19983177154329 3329685283

- AsunciónMCalvoRMSan MillánJLSanchoJAvilaSEscobar-MorrealeHFA prospective study of the prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected Caucasian women from SpainJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20008572434 243810902790

- AmerSAPolycystic ovarian syndrome: diagnosis and management of related infertilityObstet Gynaecol Reprod Med20091910263 270

- BalenAThe pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome: trying to understand PCOS and its endocrinologyBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol2004185685 70615380141

- Diamanti-KandarakisEPolycystic ovarian syndrome: pathophysiology, molecular aspects and clinical implicationsExpert Rev Mol Med200810e318230193

- DeugarteCMWoodsKSBartolucciAAAzzizRDegree of facial and body terminal hair growth in unselected black and white women: toward a populational definition of hirsutismJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20069141345 135016449347

- Escobar-MorrealeHFLuque-RamírezMGonzálezFCirculating inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysisFertil Steril20119531048 1058e1 e221168133

- FranksSGharaniNMcCarthyMCandidate genes in polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod Update200174405 41011476353

- MoranLNormanRJUnderstanding and managing disturbances in insulin metabolism and body weight in patients with polycystic ovary syndromeBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol2004185719 73615380143

- NormanRJMastersSHagueWHyperinsulinemia is common in family members of women with polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril1996666942 9478941059

- BoekaAGLokkenKLNeuropsychological performance of a clinical sample of extremely obese individualsArch Clin Neuropsychol2008234467 47418448310

- GambineriAPelusiCVicennatiVPagottoUPasqualiRObesity and the polycystic ovary syndromeInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord2002267883 89612080440

- MustAJSpadanoEHCoakleyAEColditzEADietzWHThe disease burden associated with overweight and obesityJAMA1999282161523 152910546691

- PasqualiRGambineriAPagottoUThe impact of obesity on reproduction in women with polycystic ovary syndromeBJOG2006113101148 115916827825

- SvendsenMRissanenARichelsenBRössnerSHanssonFTonstadSEffect of orlistat on eating behavior among participants in a 3-year weight maintenance trialObesity (Silver Spring)2008162327 33318239640

- BruceACMcNurlanMAMcHardyKCNutrient oxidation patterns and protein metabolism in lean and obese subjectsInt J Obes1990147631 6462228398

- RobinsonSChanSPSpaceySAnyaokuVJohnstonDGFranksSPostprandial thermogenesis is reduced in polycystic ovary syndrome and is associated with increased insulin resistanceClin Endocrinol (Oxf)1992366537 5431424179

- JeanesYBarrSSharpKReevesSEating behaviours and BMI in women with polycystic ovary syndromeProc Nutr Soc201069OCE1E57

- MoranLJPasqualiRTeedeHJHoegerKMNormanRJTreatment of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement of the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome SocietyFertil Steril20099261966 198219062007

- ClarkAMThornleyBTomlinsonLGalletleyCNormanRJWeight loss in obese infertile women results in improvement in reproductive outcome for all forms of fertility treatmentHum Reprod19981361502 15059688382

- CrosignaniPGColomboMVegettiWSomiglianaEGessatiARagniGOverweight and obese anovulatory patients with polycystic ovaries: parallel improvements in anthropometric indices, ovarian physiology and fertility rate induced by dietHum Reprod20031891928 193212923151

- Huber-BuchholzMMCareyDGNormanRJRestoration of reproductive potential by lifestyle modification in obese polycystic ovary syndrome: role of insulin sensitivity and luteinizing hormoneJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19998441470 147410199797

- MoranLJNoakesMCliftonPMWittertGAWilliamsGNormanRJShort-term meal replacements followed by dietary macronutrient restriction enhance weight loss in polycystic ovary syndromeAm J Clin Nutr200684177 8716825684

- TolinoAGambardellaVCaccavaleCEvaluation of ovarian functionality after a dietary treatment in obese women with polycystic ovary syndromeEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2005119187 9315734091

- NestlerJEJakubowiczDJLean women with polycystic ovary syndrome respond to insulin reduction with decreases in ovarian P450c17α activity and serum androgensJ Clin Endocrinol Metab199782124075 40799398716

- KiddyDSHamilton-FairleyDBushAImprovement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with polycystic ovary syndromeClin Endocrinol (Oxf)1996361105 1111559293

- MavropoulosJCYancyWSHepburnJWestmanECThe effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot studyNutr Metab (Lond)200523516359551

- HolteJBerghTBerneCWideLLithellHRestored insulin sensitivity but persistently increased early insulin secretion after weight loss in obese women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19958092586 25937673399

- HerriotAMWhittcroftSJeanesYA retrospective audit of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: the effects of a reduced glycaemic load dietJ Hum Nutr Diet2008214337 34518721400

- JeanesYMBarrSSmithKHartKHDietary management of women with polycystic ovary syndrome in the United Kingdom: the role of dietitiansJ Hum Nutr Diet2009226551 55819735349

- NicholsonFRollandCBroomJLoveJEffectiveness of long term (twelve months) nonsurgical weight loss interventions for obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic reviewInt J Womens Health20102393 39921151687

- AtkinsonRLDietzWHForeytJPVery low-calorie diets. National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity, National Institutes of HealthJAMA19932708967 9748345648

- MulhollandYNicokavouraEBroomJRollandCVery-low-energy diets and morbidity: a systematic review of longer-term evidenceBr J Nutr20121085832 85122800763

- Van ItallieTBLiquid protein mayhemJAMA19782402144 145660833

- Centers For Disease Control and PreventionLiquid Protein Diets Public Health Service ReportAtlantaCDC1979

- DhindsaPScottARDonnellyRMetabolic and cardiovascular effects of very-low-calorie diet therapy in obese patients with type 2 diabetes in secondary failure: outcomes after 1 yearDiabet Med2003204319 32412675647

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceObesity: Identification, Assessment and Management of Overweight and Obesity in Children, Young People and AdultsLondonNICE2014

- Van DamEWRoelfsemaFVeldhuisJDIncrease in daily LH secretion in response to short-term calorie restriction in obese women with PCOSAm J Physiol Endocrinol Metab20022824E865 E87211882506

- Van DamEWRoelfsemaFVeldhuisJDRetention of estradiol negative feedback relationship to LH predicts ovulation in response to caloric restriction and weight loss in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndromeAm J Physiol Endocrinol Metab20042864E615 E62014678951

- BuckroydJRotherSTherapeutic Groups for Obese Women: A Group Leader’s HandbookChichester, UKWiley & Sons Ltd2007

- ChastonTBDixonJBFactors associated with percent change in visceral versus subcutaneous abdominal fat during weight loss: findings from a systematic reviewInt J Obes (Lond)2008324619 62818180786

- CooperZFairburnCGHawkerDCognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Obesity: A Clinician’s GuideNew YorkGuilford Press2003

- Scottish GovernmentNational Infertility Group ReportEdinburghScottish Government2013 Available from: http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0042/00421950.pdfAccessed September 1, 2014

- GeorgopoulosNASaltamavrosADVervitaVBasal metabolic rate is decreased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and biochemical hyperandrogenemia and is associated with insulin resistanceFertil Steril2009921250 25518678372

- RollandCLulaSJennerCWeight loss for individuals with type 2 diabetes following a very-low-calorie diet in a community-based setting with trained facilitators for 12 weeksClin Obes201335150 15725586630

- HirschbergALNaessénSStridsbergMByströmBHoltetJImpaired cholecystokinin secretion and disturbed appetite regulation in women with polycystic ovary syndromeGynecol Endocrinol200419279 8715624269

- ChearskulSDelbridgeEShulkesAProiettoJKriketosAEffect of weight loss and ketosis on postprandial cholecystokinin and free fatty acid concentrationsAm J Clin Nutr20088751238 124618469245

- MoranLJNoakesMCliftonPMTomlinsonLGalletlyCNormanRJDietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2003882812 81912574218

- StametsKTaylorDSKunselmanADemersLMPelkmanCLLegroRSA randomized trial of the effects of two types of short-term hypocaloric diets on weight loss in women with polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril2004813630 63715037413

- AvenellABroomJBrownTJSystematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvementHealth Technol Assess2004821iii iv1 18215147610

- ChenMJYangWSYangJHChenCLHoHNYangYSRelationship between androgen levels and blood pressure in young women with polycystic ovary syndromeHypertension20074961442 144717389259

- Bentley-LewisRSeelyEDunaifAOvarian hypertension: polycystic ovary syndromeEndocrinol Metab Clin North Am2011402433 44921565677

- LoJCFeigenbaumSLYangJPressmanARSelbyJVGoASEpidemiology and adverse cardiovascular risk profile of diagnosed polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20069141357 136316434451

- Luque-RamírezMAlvarez-BlascoFMendieta-AzconaCBotella-CarreteroJIEscobar-MorrealeHFObesity is the major determinant of the abnormalities in blood pressure found in young women with the polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20079262141 214817389696