Abstract

Hypertension is a common and important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular and kidney diseases. The prevalence of hypertension, particularly isolated systolic hypertension, increases with advancing age, and this is partly due to the age-related changes in the arterial tree, leading to an increase in arterial stiffness. Therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as reduced dietary sodium intake, weight loss, regular aerobic activity, and moderation of alcohol consumption, have been shown to benefit elderly patients with hypertension. Lowering blood pressure (BP) using pharmacological agents reduces the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, with no difference in risk reduction in elderly patients compared to younger hypertensives. Guidelines recommend a BP goal of <140/90 in hypertensive patients regardless of age and <130/80 in patients with concomitant diabetes or kidney disease, and lowering the BP further has not been shown to confer any additional benefit. Moreover, the choice of antihypertensive does not seem to be as important as the degree of BP lowering. Special considerations in the treatment of elderly hypertensive patients include cognitive impairment, dementia, orthostatic hypotension, and polypharmacy.

Hypertension affects 26.4% of the global population, affecting about 972 million individuals worldwide, and patients with elevated blood pressure (BP) are projected to comprise 29.2% of the world population in 2025.Citation1 The prevalence of hypertension increases with advancing age, such that as much as half of individuals aged between 60 and 69 years are hypertensive, and this increases to 60%–70% in people above the age of 70.Citation1 Further, the lifetime risk for developing hypertension in normotensive individuals aged between 55 and 65 years is >90%.Citation2

Hypertension is an important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular and kidney diseases. Elevations in BP beyond 115/75 mmHg increase the risk for death from ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke in a log-linear fashion, such that the risk of dying from IHD or stroke is doubled for every 20/10 mmHg increase in BP.Citation3 After the age of 50, systolic BP (SBP) is more important than diastolic BP (DBP) in predicting adverse cardiovascular outcomes. This is attributed to the age-related increase in SBP, whereas DBP tends to decline after 60 years of age, such that majority of elderly individuals have isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) and increased pulse pressure (PP).Citation4 The risk for all-cause and cardiovascular death is positively correlated to the increase in SBP and PP in elderly patients and inversely correlated to DBP.Citation5,Citation6

This phenomenon of increased SBP and PP in elderly hypertensives is partly explained by increased arterial stiffness with advancing age. Structural changes in the arterial media, which include declining vascular smooth muscle cell number coupled with increased collagen content in the vessel wall, calcium deposition, and disruption of elastic fibers, result in a markedly stiffer vessel with decreased capacitance and loss of recoil.Citation7 The limited expansion of the stiff arterial tree (which is most marked at the level of the large elastic arteries) leads to a rise in peak BP, whereas the limited recoil results in a decline in DBP. These changes also result in an increased pulse wave velocity (PWV), where pulse waves generated by cardiac contractions are propagated faster along the stiff artery. Increased PWV has been shown to independently predict cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in elderly patients with hypertension.Citation8 As a corollary, increased PWV in middle age (mean 53 ± 17 years old) was an independent predictor of longitudinal increase in SBP after a mean follow-up of 4.3 years.Citation9

Diagnosis

National guidelines define hypertension and recommend the initiation of antihypertensive treatment when the BP exceeds 140/90 mmHg. In those with diabetes, kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease, antihypertensive treatment is recommended if BP exceeds 130/85 mmHg.Citation10–Citation14 Office BP is the usual method for BP measurement, and this is ideally performed in a seated patient with the arm propped at the level of the heart. The average of two BP readings from the same arm is preferred, which is taken after at least 5 min of rest.

After the diagnosis of hypertension is confirmed, the evaluation is now directed at assessing lifestyle, looking for cardiovascular risk factors, identifying secondary causes of hypertension, as well as searching for evidence of target organ damage.

Secondary causes

In more than 90% of hypertensive patients, there is no identifiable cause for the elevated BP (primary or essential hypertension). In the remainder, the elevated BP is attributable partly or wholly to a specific cause, which may be potentially reversible. Common secondary causes of hypertension in the elderly include chronic kidney disease (CKD) and renal artery stenosis. Other causes include obstructive sleep apnea, primary aldosteronism, Cushing’s disease, pheochromocytoma, hyperparathyroidism, aortic coarctation, and intracranial tumors.

CKD can be a cause or a result of hypertension. A decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with aging occurs in most individuals (but is not inevitable), and this is pronounced in those with hypertension and atherosclerosis and in smokers. As such, the incidence of CKD increases with advancing age, where the odds ratio for the development of CKD is 1.58 and 5.53 in those aged 40–59 years and those aged 60 years and older, respectively.Citation15 In elderly patients with ISH, SBP is a strong and independent predictor of the decline in renal function.Citation16 At present, estimation of the GFR using the Modified Diet in Renal Disease formula or the Cockcroft–Gault equation provides a better gauge of kidney function than serum creatinine alone and is preferably paired with a urinalysis to check for albuminuria.Citation17 It is important to screen for CKD, if present, as this has implications in terms of choice of antihypertensive agents and BP goals.

In the elderly, stenosis of the renal artery is often due to atherosclerosis. About 7% of individuals aged over 65 years have some degree of renal artery narrowing, and 60% of patients have hypertension or other evidence of atherosclerotic disease (coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease).Citation18 Renal artery stenosis should be suspected in an elderly patient who presents with new onset or accelerated hypertension (with worsening BP control), in patients with resistant hypertension (who need three or more medications to bring the BP to goal), in patients with asymmetric kidneys on imaging (a difference of greater than 1.5 cm), and in those who present with flash pulmonary edema or acute renal failure after initiating renin–angiotensin system blocker therapy (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers [ARB], or direct renin inhibitors).Citation19 Imaging techniques used to evaluate the patency of the renal artery include renal Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography and are used as screening tests. The gold standard for diagnosis remains renal artery angiography. Treatment includes modification of cardiovascular risk factors, antihypertensive therapy, and in eligible patients, revascularization, but this has not consistently been shown to normalize BP in hypertensive patients.Citation18

Treatment

Lifestyle changes

Important lifestyle modifications to help lower BP in hypertensive patients include dietary sodium reduction, weight loss and maintenance of ideal body weight, regular aerobic activity, and moderation of alcohol intake (). The Trial of Non-Pharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE) randomized 975 patients aged 60–80 years with hypertension (BP < 145/85 mmHg while taking one antihypertensive medication) to sodium reduction, weight loss, a combination of both, or usual care for the obese participants and to sodium reduction and usual care in the nonobese patients.Citation20 The study participants attended group intervention sessions, and 90 days after their first session, the patients were weaned from their antihypertensive medication, with a goal of discontinuing the drug altogether. The primary endpoints were the finding of elevated BP (SBP > 190 mmHg or DBP > 110 mmHg at one study visit; or mean SBP > 170 mmHg or mean DBP > 100 mmHg over two sequential visits; or mean SBP > 150 mmHg or mean DBP > 90 mmHg over three sequential visits) at one or more study visits after drug discontinuation or weaning, the need to reinstitute antihypertensive therapy, as well as cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, angioplasty, or coronary bypass surgery), and death.

Table 1 Degree of BP reduction achieved with lifestyle modifications in elderly patients with hypertension

The obese participants in TONE who were randomized to the weight loss and combination arms were given a weight loss goal of −4.5 kg, using a combination of diet and increased physical activity. The average weight loss among participants in the weight loss arm was 3.5 kg, and 47% achieved the goal of −4.5 kg after 9 months. This resulted in 39% of subjects in the weight loss arm not experiencing a rise in BP or a need to reinstitute BP-lowering medications for 30 months after discontinuing antihypertensive drugs. In patients who were randomized to the sodium reduction and combination arms, only 36% achieved the goal to reduce sodium intake to <80 mmol/day (1.8 g/day). In spite of this, 72% of those assigned to a low-sodium diet had their BP controlled to <140/90 mmHg, and 38% of these remained off antihypertensive medications for 30 months. The mean SBP and DBP values prior to the initiation of antihypertensive drug withdrawal were significantly lower in all intervention groups compared to usual care. TONE showed that nonpharmacological interventions to lower BP, particularly reduced sodium intake and weight loss (via diet and increased physical activity), result in clinically important reductions in need for antihypertensive medications in elderly hypertensive patients.

In addition to reduction of sodium, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products, with limited cholesterol and saturated fat, is recommended for hypertensive patients (the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension or the DASH diet), except for those with CKD, in whom the increased potassium and protein may be harmful.Citation21 Dietary modification is an important nonpharmacological intervention to reduce BP in elderly patients with hypertension.

In elderly hypertensive patients, regular aerobic exercise, consisting of a minimum of 30 min of interval training on a treadmill done three times a week, has been shown to be well tolerated and beneficial.Citation22 Adherence to the 12-week exercise program in this study lowered SBP by 8.5 mmHg, DBP by 5.1 mmHg, and PP by 3.2 mmHg from baseline on 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring in elderly hypertensive patients on a stable antihypertensive drug regimen. This effect was not seen in the control group, who were sedentary, in whom the BP values were similar at baseline and after 12 weeks of follow-up. Further, there was marked improvement of physical performance in the exercise group compared to the sedentary group, as measured by a rightward shift in the lactate and heart rate curves after 12 weeks. One patient dropped out from the study due to knee pain, and another developed acute cholecystitis after 4 weeks; otherwise, no severe adverse events were noted during the course of the study. In elderly hypertensive patients without contraindications, regular physical activity is beneficial and safe and should be encouraged.

Pharmacological treatment

Benefits of pharmacological treatment of hypertension in the elderly

In elderly hypertensive patients, lowering the BP reduces the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The benefits achieved with BP reduction in the elderly are similar to that in younger hypertensive patients. The Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration pooled data from 31 trials, involving 190,606 individuals, that compared active antihypertensive treatment to placebo or a less intensive regimen, as well as trials that compared different antihypertensive regimens.Citation23 It showed that there was no difference in the incidence of cardiovascular outcomes (fatal and nonfatal stroke, coronary heart disease, and heart failure) in patients aged 65 years and older compared to hypertensive individuals aged under than 65 years. Further, there was no difference in the risk reduction achieved between the two age groups per unit reduction in BP. There was also no interaction between age and the effects of treatment on the primary outcome for any antihypertensive regimen compared to control.

Individual trials quantify the magnitude of risk reduction achieved with BP lowering. The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) evaluated the ability of chlorthalidone with or without atenolol versus placebo in reducing the risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke in elderly patients (≥60 years old) with ISH.Citation24 Compared to placebo, active treatment reduced the risk of stroke by 36% after an average of 4.5 years of follow-up (P = 0.0003). The Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial (SYST-EUR) was done on 4695 patients who were ≥60 years old with ISH (SBP on study entry >160 mmHg).Citation25 The study participants were randomized to receive either nitrendipine 10–40 mg/day with the possible addition of enalapril 5–20 mg/day and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5–25 mg/day or matching placebos. SYST-EUR showed that active treatment reduced the rate of primary endpoints (fatal and nonfatal stroke) by 42% (P = 0.003) and all fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular endpoints (stroke, retinopathy, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and renal insufficiency) by 31% (P < 0.001) compared to placebo after a mean follow-up of 2 years. A similar study, the Systolic Hypertension in China trial (SYST-CHINA), which randomized 2394 hypertensive patients aged 60 or older, demonstrated that active treatment (nitrendipine 10–40 mg/day, with the addition of captopril 12.5–50 mg/day or hydrochlorothiazide 12.5–25 mg/day or both, is administered to achieve an SBP goal of <150 mmHg) reduced the incidence of total strokes by 38% (P = 0.01), stroke deaths by 58% (P = 0.02), cardiovascular mortality by 39% (P = 0.03), and all fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular endpoints (similar to the SYST-EUR trial) by 37% (P = 0.004) compared to placebo.Citation26

A meta-analysis of eight trials on elderly hypertensive patients has shown that antihypertensive treatment reduced total mortality by 13% (P = 0.02), cardiovascular deaths by 18%, stroke by 30%, and coronary events by 23% compared to control (placebo or a less intensive antihypertensive regimen).Citation6 The absolute benefit was found to be higher in men, in patients who were >70 years old, and in those with previous cardiovascular disease or higher PP. These data provide strong support that BP lowering in the elderly significantly reduces cardiovascular risk.

Early treatment of hypertension in elderly patients as opposed to delayed treatment also produces greater cardiovascular risk lowering. In the open-label follow-up of 3517 patients from the SYST-EUR Study (where median follow-up was 6.1 years), those who had received active treatment during the double-blind phase of the trial had 28% less incidence of stroke and 15% less cardiovascular complications compared to those patients who were randomized to receive placebo during that period (P = 0.01 and P = 0.03, respectively).Citation27 Given the high incidence of ISH in the elderly population, early recognition and initiation of therapy are important.

Lastly, the benefit of hypertension treatment has been shown to persist long after the termination of studies. In the 14-year follow-up of SHEP participants, those who had received active treatment with chlorthalidone with or without atenolol during the trial had fewer deaths from cardiovascular causes (P = 0.016), without a significant difference in all-cause mortality or stroke deaths compared to those randomized to placebo.Citation28 Further, those who had sustained a stroke during the trial had a worse prognosis compared to those who were stroke free, and the predictors of death included SBP, diabetes, and smoking, which are modifiable. This highlights the fact that in elderly hypertensive patients who had a stroke, control of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors may help decrease the long-term risk of death.

Goal of antihypertensive therapy

The guidelines in the management of hypertension recommend a BP goal of <140/90 mmHg in hypertensive patients and <130/80 in patients with diabetes and kidney diseases, irrespective of age.Citation10–Citation14 While at best prudent, it is not backed by solid evidence showing that treating hypertension to these BP goals provides additional cardiovascular risk reduction. Major placebo-controlled trials involving elderly hypertensive patients enrolled individuals with a baseline SBP > 160 mmHg, and the treatment goal was <150 mmHg in most studies. In a prospective study done in Italy, 1111 nondiabetic hypertensive patients (mean age 67) were randomized to receive open-label antihypertensive treatment to lower SBP to <140 mmHg in one group and <130 mmHg in another.Citation29 The primary endpoint was the incidence of left ventricular hypertrophy after 2 years of follow-up. The study showed that patients who were randomized to SBP lowering to <130 mmHg had less incidence of left ventricular hypertrophy compared to those randomized to the SBP goal of <140 mmHg (11.4% and 17%, respectively, P = 0.013). The difference in SBP achieved after the 2-year follow-up between the two groups, however, was only 3.8 mmHg, so the effect of choice of antihypertensive medication may have influenced the results.

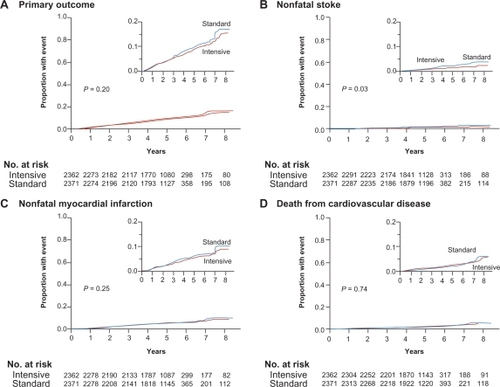

In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes–Blood Pressure trial (ACCORD BP), 4733 middle-aged and elderly participants (mean age 62 years) with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular disease, evidence of target organ damage, or at least two cardiovascular risk factors were randomly assigned in a 2 × 2 factorial design to intensive (SBP < 120 mmHg) versus standard (SBP < 140 mmHg) BP control.Citation30 Antihypertensive medications were given open-label, and the study did not specify the drug class that would be used for lowering BP in both groups. After a mean follow-up of 4.7 years, the BP decreased from a mean of 139/76 mmHg in both groups to 119/64 mmHg in the intensive BP-lowering group and 133/70 mmHg in the standard control group, which resulted in a 14/6 mmHg difference between the two groups (). As expected, those in the intensive BP-lowering group were on greater numbers of antihypertensive agents. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of major cardiovascular events, which include the composite of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and cardiovascular death. Moreover, there was a higher incidence of adverse events in the intensive treatment group that are attributable to antihypertensive therapy, which include hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, and arrhythmia, as well as hypokalemia and elevations in serum creatinine. On the other hand, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of total stroke and nonfatal stroke (which are two of several prespecified secondary outcomes) in the intensive BP control compared to standard BP control. The ACCORD Study, however, is limited by the low occurrence of cardiovascular events during the study duration in the standard control group, which may have minimized a probable difference in outcomes, if any, between the two groups. Nevertheless, the ACCORD results, while showing that SBP lowering to <120 mmHg reduces the risk for stroke, did not support further lowering of SBP beyond 140 mmHg in improving cardiovascular outcomes in middle-aged and elderly hypertensive patients with diabetes and may in fact lead to a higher incidence of adverse effects related to treatment. Whether this is true for nondiabetic elderly patients and older patients with kidney disease is still controversial.

Figure 1 Comparison of intensive versus standard BP lowering on the composite of nonfatal stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and death from cardiovascular disease (primary outcome). Copyright © 2010. Adapted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al., for the ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585.Citation30

Choice of antihypertensive agents

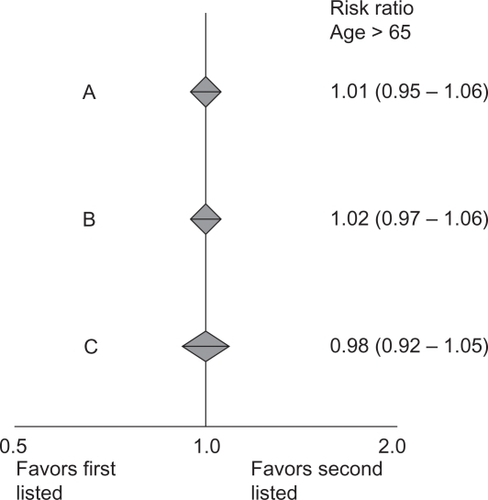

The presence of comorbidities, history of adverse reactions to medications, cost, ease of dosage, and patient preference influence the choice of antihypertensive agents in elderly patients. A large meta-analysis has shown that the choice of antihypertensive agent does not influence outcomes, ie, the benefit derived from BP reduction is similar in magnitude and independent of the antihypertensive agent used to create such effect, regardless of the patient’s age.Citation23 Data comparing diuretics or beta blockers (BB) versus ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers (CCB), as well as ACE inhibitors versus CCB, show that there was no difference in the proportional reduction of cardiovascular risk between the different antihypertensive regimens in patients >65 years of age (). Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARB, BB, CCB, and aldosterone antagonists, either singly or in combination, are all acceptable options as initial antihypertensive agents in elderly patients. Guidelines in managing hypertensive patients specify particular agents to use in certain disease conditions, such as coronary artery disease, renal disease, and diabetes, where the preferred agent has been found, in clinical trials, to have favorable effects in specific clinical settings.

Figure 2 Comparison of different BP-lowering regimens in reducing cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients >65 years old. A) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor versus diuretic or beta blocker. B) Calcium antagonist versus diuretic or beta blocker. C) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor versus calcium antagonist. Copyright © 2008. Adapted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Turnbull F, for the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2008;336:1121–1123.Citation23

Most hypertensive patients would need two or more antihypertensive agents to bring the BP to goal. Combination therapy using agents with complementary mechanisms of action is favorable because it allows the use of antihypertensive medications at lower doses than if the medication was used singly, thereby also minimizing the incidence of adverse effects. Further, the use of combination therapy at the outset, particularly in high-risk patients, reduces cardiovascular risk by giving early BP control.Citation11 Fixed-dose combination pills are preferred by most physicians and are recommended by certain guidelines as they may lower overall cost and improve adherence to treatment.Citation31

Acceptable antihypertensive drug combinations include a renin–angiotensin system blocker and a diuretic or CCB, as well as BB and a diuretic. Several trials have demonstrated the benefit of these combinations in reducing cardiovascular risk in elderly patients with hypertension. For example, in SHEP, chlorthalidone with atenolol reduced the risk for fatal and nonfatal stroke compared to placebo.Citation24 SYST-EUR (where as much as 80% of the study participants were on combination antihypertensive therapy during the first year of the trial) and SYST-CHINA showed that CCB-based therapy combined with an ACE inhibitor and a thiazide diuretic reduced the incidence of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, particularly fatal and nonfatal stroke, and the composite of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular endpoints.Citation25,Citation26 Other large outcome trials, which did not exclusively involve elderly patients, have also shown that combination antihypertensive therapy is beneficial. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Blood Pressure Lowering Arm, conducted in 19,257 high-risk hypertensive patients (mean age 63) and comparing amlodipine with or without perindopril versus atenolol with or without bendroflumethiazide, found that the treatment based on amlodipine was superior in preventing a composite of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke with a similar degree of BP reduction.Citation32 The Avoiding Cardiovascular Events thru Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial, which had a predominantly elderly patient population (mean age 68), demonstrated that an ACE inhibitor–CCB combination (benazepril and amlodipine) was effective in preventing a composite of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular endpoints and was superior (19.6% less events) to a combination of an ACE inhibitor and a diuretic (benazepril and hydrochlorothiazide) in spite of a similar degree of BP reduction in both groups.Citation33 The last two studies imply that cardiovascular risk lowering is not entirely dependent on BP lowering in some antihypertensive treatment trials.

Treating the very elderly

In the past, treatment of BP in the very elderly was controversial. This subgroup of patients is usually excluded from clinical trials, and the data available to demonstrate treatment benefits were limited and inconclusive. Further, the benefits of antihypertensive therapy could be potentially offset by complications of treatment, which are seen as occurring more commonly in the elderly, such as dementia, orthostatic hypotension, heart failure, and electrolyte abnormalities. This clinical uncertainty with regards to the relative benefits and risks associated with antihypertensive therapy in patients >80 years old was addressed by the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). HYVET enrolled 3845 hypertensive patients who were >80 years old with a baseline SBP >160 mmHg and randomized them to receive indapamide or placebo.Citation34 Perindopril or placebo was added on later if the BP was still above goal (<150/80 mmHg). The results show that active treatment was associated with a 30% reduction in fatal or nonfatal stroke (P = 0.06), a 39% reduction in stroke deaths (P = 0.06), a 21% decrease in all-cause mortality (P = 0.02), and a 23% decline in cardiovascular death after a median follow-up of 1.8 years. Further, there was a 64% reduction of heart failure (P < 0.001). This was achieved without an excess of adverse events in the active treatment arm compared to placebo. The incidence of potassium abnormalities or increase in serum creatinine, uric acid, or glucose was similar in the active and placebo treatment arms. Orthostatic hypotension occurred in 12% of study participants in the pilot trial, but the authors counter that this higher than expected number could be due to selection bias as those with SBP > 140 mmHg were excluded from the analysis.Citation35 This trial gave conclusive evidence that even in the very elderly (>80 years old), treatment of hypertension reduces cardiovascular risk significantly. A caveat, however, is that HYVET excluded nursing home residents, patients with dementia, and those with kidney disease or heart failure, which comprise a significant subset in this age group; hence, these results may not be generalized to all elderly patients >80 years of age.

Other considerations in the treatment of elderly hypertensive patients

The treatment of elderly hypertensive patients is complicated by many factors. Orthostatic hypotension, defined as a supine-to-standing BP difference of −20/–10 mmHg, occurs more commonly in the elderly, owing to a blunted baroreflex response that occurs with standing.Citation36 Initiating antihypertensive medications at low doses and making gradual adjustments, and obtaining a standing BP when increasing medication doses in symptomatic patients are part of a good practice. In addition, elderly patients frequently take multiple medications for other comorbid conditions, so the possibility of drug interactions is high. This is particularly true for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which may interfere with the actions of antihypertensive medications, and may lead to poor BP control.Citation37 Polypharmacy may also lead to poor compliance in elderly patients, so simplification of the drug regimen is encouraged.

Cognitive impairment is common in the elderly population. Hypertension has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and dementia in the elderly. Elevated BP during middle age predicts the development of dementia with aging.Citation38 Further, a high SBP (>180 mmHg) and a low DBP (<70 mmHg) increase the risk of dementia in older adults.Citation39 Antihypertensive treatment lowers this risk as shown in SYST-EUR, where active treatment is associated with a 65% lower risk of dementia compared to placebo.Citation40 In treating hypertensive patients with cognitive impairment, simplifying the treatment regimen, regular follow-ups, and involving caregivers are all part of optimal BP management.

Summary

Hypertension is a common and very important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The prevalence of hypertension increases with advancing age, and this is accounted for partly by age-related changes in the arterial tree. Initiating antihypertensive treatment is recommended when BP exceeds 140/90 mmHg (130/85 mmHg in those with diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease). Therapeutic lifestyle changes should be encouraged in elderly hypertensive patients and include dietary sodium restriction, increased physical activity, weight loss and maintenance of ideal body weight, and moderation of alcohol consumption. In the elderly, pharmacological treatment of hypertension provides significant reductions in cardiovascular risk. The degree of BP reduction achieved appears to be more important than the choice of antihypertensive agent, and this is true for younger and older patients. Combination antihypertensive therapy is usually indicated in elderly hypertensive patients, and acceptable regimens include a renin–angiotensin system blocker and a diuretic or a CCB. Treatment of hypertension in elderly patients is confounded by a greater tendency to develop orthostatic hypotension, polypharmacy, and a higher incidence of cognitive impairment.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKMuntnerPWheltonPKHeJGlobal burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide dataLancet200536521722315652604

- VasanRSBeiserASeshadriSResidual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: the Framingham Heart StudyJAMA20022871003101011866648

- Prospective Studies CollaborationAge-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet20023601903191312493255

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working GroupNational High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group report on hypertension in the elderlyHypertension1994237585

- Pastor-BarriusoRBanegasJRDamianJAppelLJGuallarESystolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure: an evaluation of their joint effect on mortalityAnn Intern Med200313973173914597457

- StaessenJAGasowskiJWangJGRisk of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trialsLancet200035586587210752701

- DaoHHEssalihiRBouvetCMoreauPEvolution and modulation of age-related medial elastocalcinosis: impact on large artery stiffness and isolated systolic hypertensionCardiovasc Res20056630731715820199

- Sutton-TyrrellKNajjarSSBoudreauRMElevated aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness, predicts cardiovascular events in well-functioning older adultsCirculation20051113384339015967850

- NajjarSSScuteriAShettyVPulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of AgingJ Am Coll Cardiol2008511377138318387440

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRJoint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension2003421206125214656957

- ManciaGLaurentSAgabiti-RoseiEReappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force documentBlood Press20091830834720001654

- Guidelines Sub-Committee1999 World Health organization/International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertensionJ Hypertens19991715118310067786

- PadwalRSHemmelgarnBRKhanNAfor the Canadian Hypertension education programThe 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of riskCan J Cardiol20092527928619417858

- SanchezRAAyalaMBaglivoHfor the Latin America Expert GroupLatin American guidelines on hypertensionJ Hypertens20092790592219349909

- United States Renal Data System Annual Data ReportBethesda, MDUS Department of Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health2009

- YoungJHKlagMJMuntnerPBlood pressure and decline in kidney function: Findings from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP)J Am Soc Nephrol2002132776278212397049

- National Kidney FoundationK/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratificationAm J Kidney Dis200239S1S26611904577

- GottamNNanjundappaADieterRSRenal artery stenosis: pathophysiology and treatmentExpert Rev Cardiovasc Ther200971413142019900024

- HirschATHaskalZJHertzerNRACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic)J Am Coll Cardiol2006471239131216545667

- WheltonPKAppelLJEspelandMASodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older personsJAMA19982798398469515998

- AppelLJMooreTJObarzanekEA clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressureN Engl J Med1997336111711249099655

- WesthoffTHFrankeNSchmidtSToo old to benefit from sports? The cardiovascular effects of exercise training in elderly subjects treated for isolated systolic hypertensionKidney Blood Press Res20073024024717575470

- TurnbullFfor the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ CollaborationEffects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trialsBMJ20083361121112318480116

- SHEP Cooperative Research GroupPrevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP)JAMA1991265325532642046107

- StaessenJAFagardRThijsLRandomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertensionLancet19973507577649297994

- LiuLWangJGGongLComparison of active treatment and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertensionJ Hypertens199816182318299869017

- StaessenJAThijsLFagardREffects of immediate versus delayed antihypertensive therapy on outcome in the Systolic Hypertension in Europe TrialJ Hypertens20042284785715126928

- PatelABKostisJBWilsonACFourteen-year follow-up of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly ProgramStroke2008391084108918309155

- VerdecchiaPStaessenJAAngeliFUsual versus tight control of systolic blood pressure in non-diabetic patients with hypertension (Cardio-Sis): an open label randomised trialLancet200937452553319683638

- CushmanWCEvansGWByingtonRPfor the ACCORD Study GroupEffects of intensive blood pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitusN Engl J Med20103621575158520228401

- DicksonMPlauschinatCACompliance with anti-hypertensive therapy in the elderlyAm J Cardiovasc Drugs200881455018303937

- DahlofBSeverPSPoulterNRPrevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding benzoflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial – Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomized controlled trialLancet200536689590616154016

- JamersonKWeberMABakrisGLBenazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patientsN Engl J Med2008359232417242819052124

- BeckettNSPetersRFlaetcherAETreatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or olderN Engl J Med2008358181887189818378519

- BeckettNSConnorMSadlerJDOrthostatic fall in blood pressure in the very elderly hypertensive: results from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) – pilotJ Hum Hypertens19991383984010618673

- ShiXWrayWFormesKJOrthostatic hypotension in aging humansAm J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol2000279H1548H155411009440

- IshiguroCFukitaTOmoriTAssessing the effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on anti-hypertensive drug therapy using post-marketing surveillance databaseJ Epidemiol200818311912418469490

- LaunerLMasakiKPetrovitchHThe association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive functionJAMA1995274184618517500533

- QiuCWinbladBFratiglioniLThe age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementiaLancet Neurol2005448749916033691

- ForetteFSeuxMStaessenJPrevention of dementia in a randomised double blind placebo controlled systolic hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trialLancet1998352134713519802273

- AcelajadoMCOparilSOHypertension in the elderlyClin Geriatr Med20092539149219765488