Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency is a common problem in primary care and is usually treated with oral iron substitution. With the recent simplification of intravenous (IV) iron administration (ferric carboxymaltose) and its approval in many countries for iron deficiency, physicians may be inclined to overutilize it as a first-line substitution.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate iron deficiency management and substitution practices in an academic primary care division 5 years after ferric carboxymaltose was approved for treatment of iron deficiency in Switzerland.

Methods

All patients treated for iron deficiency during March and April 2012 at the Geneva University Division of Primary Care were identified. Their medical files were analyzed for information, including initial ferritin value, reasons for the investigation of iron levels, suspected etiology, type of treatment initiated, and clinical and biological follow-up. Findings were assessed using an algorithm for iron deficiency management based on a literature review.

Results

Out of 1,671 patients, 93 were treated for iron deficiency. Median patients’ age was 40 years and 92.5% (n=86) were female. The average ferritin value was 17.2 μg/L (standard deviation 13.3 μg/L). The reasons for the investigation of iron levels were documented in 82% and the suspected etiology for iron deficiency was reported in 67%. Seventy percent of the patients received oral treatment, 14% IV treatment, and 16% both. The reasons for IV treatment as first- and second-line treatment were reported in 57% and 95%, respectively. Clinical and biological follow-up was planned in less than two-thirds of the cases.

Conclusion

There was no clear overutilization of IV iron substitution. However, several steps of the iron deficiency management were not optimally documented, suggesting shortcuts in clinical reasoning.

Introduction

Anemia is a global public health problem affecting both developing and developed countries. Overall, 24.8% of females and preschool children around the world suffer from anemia, and iron deficiency is considered to be among the most important contributing factors.Citation1 Iron deficiency without anemia affects 10%–30% of menstruating females in Europe and the US.Citation2,Citation3 Although prevalence of iron deficiency depends on age, sex, and socioeconomic status,Citation4 it is a common problem in primary care and is an underrecognized cause of fatigue and other symptoms in females of childbearing age.Citation5

Oral iron administration is the first-line therapy to manage the symptoms of iron deficiency and increase the ferritin value. However, oral administration presents disadvantages, such as low absorption of iron and the high incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. In addition, it should be used with caution in patients with advanced renal failure or chronic heart failure because of decreased gastrointestinal absorption and increased iron loss, and is not indicated during flare-up of inflammatory bowel diseases.Citation6–Citation9 As a result, intravenous (IV) iron formulations have been approved in over 50 countries, including Switzerland, to correct iron deficiency among primary care patients. IV formulations may be indicated, for example, if oral therapy does not bring the expected results despite good compliance or is not tolerated by the patient.Citation10–Citation14

Increased use of IV iron has been reported in SwitzerlandCitation15 despite the lack of large-scale, good quality studies examining the effectiveness of oral and/or IV treatment for iron deficiency without anemia.Citation16 Most studies assessing the effectiveness of IV versus oral iron treatment were conducted in specific populations, such as patients with chronic renal insufficiency, inflammatory diseases, neoplastic diseases, during or after pregnancy, but not among primary care patients.Citation17–Citation21 In addition, hypersensitivity reactions after iron infusion are not negligible and can be life threatening. Transient decreases in serum phosphate below the normal range are frequent. Although these are generally asymptomatic, the long-term consequences of repeated iron infusions on bone metabolism are not known.Citation22

Several countries have developed initiatives to promote the appropriate and efficient use of the relevant tests and procedures.Citation23–Citation26 Since it is the mission of training institutions to ensure both the most rational use of medical resources and a high quality of patient care, we decided to conduct a quality improvement project on the use of oral and IV iron substitution in a division of primary care. The aim of the project was to evaluate whether iron deficiency has been managed appropriately in clinical practice 5 years after the commercialization of ferric carboxymaltose in Switzerland.

Methods

Study design and setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted in the Division of Primary Care at the Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland. The mission of this division includes delivering primary medical care to patients, providing pre-and postgraduate training in primary care, and conducting research in community-based clinics in Geneva, which is a canton of 450,000 inhabitants. The division is spread out over seven geographically distinct medical sites over the city but most clinical activities are conducted in the general outpatient clinic at the University Hospital. Each year, the clinic provides 13,000 scheduled medical consultations. It also trains 22 medical residents in ambulatory care. The patient catchment includes the general population of Geneva, particularly the socioeconomically deprived sector, including many vulnerable legal and illegal immigrants.

Selection of study subjects

All patients treated for iron deficiency in this clinic in March and April 2012 were included, excepting those with a hemoglobin level inferior to 80 g/L or a renal clearance inferior to 30 mL/min. According to our laboratory values, iron deficiency anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level of <120 g/L for females and <130 g/L for males, with a ferritin level of <100 μg/L. Ferritin reference values for of iron deficiency vary according to sex, age, and the presence of several chronic conditions (12 and 200 μg/L) and a recent review suggested to consider serum ferritin <100 μg/L as an indicator of iron deficiency for most conditions.Citation8 However, it is usually agreed that serum ferritin <10–15 μg/L represents exhausted reserves and that ferritin <30 μg/L indicates iron deficiency for patients without coexistent inflammatory disease.Citation27

Measurement and outcomes

Subjects were identified by reviewing all computerized medical files of patients who had visited the general outpatient clinic during March and April 2012 and had a documented iron supplementation prescribed. Nurses’ records were also reviewed for identification of patients who had received IV iron. A team of two residents and three chief residents developed a grid to analyze the relevant medical files and collect the following data: sociodemographic characteristics; iron, ferritin, and C-reactive protein levels; documented rationale for measuring iron levels (or presumed rationales according to symptoms or risk factors documented); suspected underlying etiology of iron deficiency (or presumed etiology according to the complementary investigations that were requested); treatment schedule; rationale for IV treatment; and, finally, the planned clinical and biological follow-up. This chart was first tested on ten medical files to evaluate the clarity and consistency of the topics and refine the rules of coding accordingly.

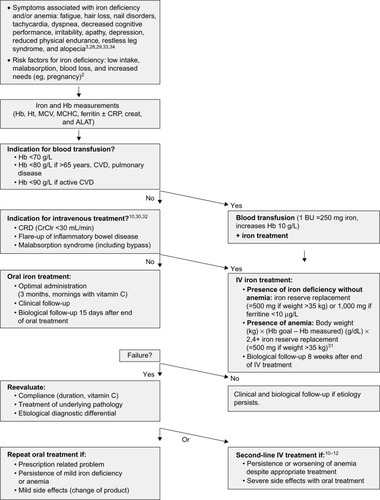

We reviewed the literature on iron deficiency detection and management and developed an algorithm based on results of scientific studies and national recommendations.Citation2,Citation3,Citation13,Citation20,Citation28–Citation32 At the end of our study, we distributed this algorithm into our Division of Primary Care medicine in order to optimize our medical practices ().

Figure 1 Algorithm for iron deficiency management.

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; Ht, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; CRP, C-reactive protein; creat, creatinine; ALAT, aspartate transaminase; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BU, blood unit; CRD, chronic renal disease; IV, intravenous.

The approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the Geneva University Hospitals and patient consent was not sought because the study was deemed an improvement activity and not a human subject research.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ sociodemographic data, ferritin levels and documented rationale for measuring iron levels, suspected etiologies, treatment schedule, reasons for choosing IV treatment, and planned clinical and biological follow-up were analyzed descriptively using mean and/or percentages. SPSS software Version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis.

Results

Out of 1,671 patients seen in March and April 2012, 97 patients were initially identified. Four patients met the exclusion criteria and so 93 patients were included in the study: 86 females and seven males. Median age was 40.2 years (standard deviation 11.8 years). In all, 81.7% (n=81) of the prescribers were residents and 12.9% (n=12) senior residents or attending physicians. Ferritin was measured in 97% (n=90) of patients and its mean value was 17.2 μg/L (standard deviation 13.3 μg/L).

The rationale for measuring iron levels was documented in 81.7% (n=76) medical files. The rationale for measuring C-reactive protein levels was documented in 30.1% (n=28) of medical files. The main reasons included presence of symptoms associated with iron deficiency, such as fatigue, or presence of risk factors for iron deficiency (mainly gynecological blood loss) (). The suspected etiology for iron deficiency was documented in 66.7% (n=62) of all cases. Gynecological and digestive blood losses were the main suspected causes. Malabsorption or low iron intakes were mentioned to a lesser extent ().

Table 1 Documented reasons for measuring iron levels and suspected etiologies of iron deficiency

The majority of patients received an oral treatment (). Out of 28 patients treated with IV iron, only seven received it as first-line and 21 as second-line treatment. The rationale for using IV iron as first-line treatment was documented in half of the cases: malabsorption (one), noncompliance (one), very low ferritin (7 μg/L) (one), and low hemoglobin (86 g/L) (one). When IV iron was used as a second-line treatment, the rationale was mentioned in 95% (n=20) of the cases: persistence of iron deficiency despite oral treatment correctly taken (n=14; 70%) and/or adverse effects of oral treatment (n=7; 35%).

Table 2 Frequency of use and documented reasons for oral or intravenous (IV) iron treatment

Clinical and biological follow-up at 3 months was planned in more than two-thirds of the patients but not all took place ().

Table 3 Clinical and biological follow-up of patients with iron deficiency

Discussion

The study shows that there was no clear overutilization of IV iron substitution in an academic division of primary care medicine 5 years after the approval of ferric carboxylmaltose for treatment of iron deficiency in Switzerland. Residents generally prescribed oral iron in first-line treatment of iron deficiency. However, several steps of the iron deficiency management were not optimally documented.

Residents did not systematically note the rationale for checking iron levels. Iron deficiency screening has not been proven to be useful as a routine procedure. Iron status should generally be requested in the presence of suggestive symptoms, such as fatigue, faintness, weakness, hair loss, loss of concentration, reduced physical endurance, and restless leg syndrome in females of childbearing age.Citation3,Citation5,Citation28,Citation29,Citation33,Citation34 It should also be determined in the presence of risk factors of iron deficiency, such as low dietary iron (vegetarian diet, socioeconomic difficulty), particularly during growth and pregnancy; diseases that impair iron absorption; gastrointestinal loss (chronic inflammatory disease, celiac disease, and cancer); gynecological or urological loss; renal or cardiac insufficiency; regular blood donations; and recent surgery.Citation2,Citation35,Citation36

Documentation of the suspected etiology was made in approximately two-thirds of medical files. The main risk factor for iron deficiency is low intake when iron requirements are especially high. However, more chronic and severe illnesses, such as gastrointestinal blood loss from an ulcer, carcinoma, or inflammatory bowel disease, or a uterine fibroma, for example, can be misdiagnosed and thus lead to poor therapeutic management.Citation5,Citation15,Citation35–Citation37

According to Swiss recommendations,Citation13 there was no clear overutilization of IV iron substitution as a first-line treatment. The majority of IV iron substitution was prescribed as a second-line treatment after a documented oral treatment failure or intolerance. However, the indication of first-line IV therapy was documented in only half of cases, suggesting that the rationale of IV treatment may not always be based on evidence. It is noted that a few studies show that IV formulations are more effective than oral forms in presence of iron deficiency from both biological and clinical perspectives (better physical or cognitive performances, decreased symptoms, decreased need for transfusions or erythropoietin).Citation15,Citation21,Citation36,Citation38,Citation39 However, oral iron substitution is still considered to be an economic and effective way to treat iron deficiency if it is taken appropriately over several months and early treatment is implemented before total exhaustion of reserves.Citation8

Finally, 70% of second-line IV therapy was prescribed for persistent iron deficiency attributed to the ineffectiveness or intolerance of oral treatment. Given the length of oral treatment and frequency of side effects, the persistence of an iron deficiency could be due to poor compliance not disclosed by the patient or a suboptimal oral intake (eg, not taken while fasting or combined with ascorbic acid). In case of intolerance, a change of formulation of oral iron substitution or time of dosing may be an appropriate strategy before considering IV treatment.

Physicians may also be put under pressure by patients’ demands for a quick IV treatment. As with the use of IV or intramuscular analgesia in case of acute pain, it may be easier to meet the demands of patients to have an IV treatment, rather than to persuade them that it is not needed or does not bring any additional benefit. Technological progress brings more and more opportunities for interventions which quickly become “state of the art” without any evidence of true superiority.Citation26

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is descriptive and retrospective, not an interventional study. Therefore, we do not know whether the guidelines created and distributed after this work improved residents’ documentation and management practices of iron deficiency. Second, we based our analysis on a review of medical files and therefore relied on documented data to assess whether clinical reasoning and practice patterns were correct. There were indeed several missing data on oral treatment noncompliance or rationale for second-line treatment. It is possible that some residents may have had correct clinical reasoning regarding measuring iron levels and subsequent management but omitted to document them sufficiently. Finally, because the study took place only in one clinical setting, our results may not be applicable to other outpatient settings. They may not be relevant for countries where IV iron supplementation for iron deficiency without anemia is neither common nor recommended, for example.

Conclusion

This study shows that in a country where IV iron substitution is recommended as a second-line treatment for iron deficiency without anemia, there was no clear overuse of it in an academic primary care division. However, several steps of iron deficiency management were not appropriately documented, suggesting lack of knowledge or clinical reasoning shortcuts that may lead to misdiagnoses of chronic diseases. More training is required in this field.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kave Sami for his help in developing the algorithm for iron deficiency management, Yann Parel for his contribution in the design of the study and the data collection and Penelope Fraser for reviewing the English.

Disclosure

Sofia Zisimopoulou received lecture fees from Kindermann communications and events (Iron Academy 2015). Bernard Favrat received study grants and lecture fees from Vifor Pharma and Pierre Fabre Medicament. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WHOWorldwide Prevalence of Anemia 1993–2005: WHO Global Database on AnemiaGenevaWorld Health Organization2008 Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/anaemia_iron_deficiency/9789241596657/en/Accessed February 21, 2016

- HercbergSPreziosiPGalanPIron deficiency in EuropePublic Health Nutr200142B53754511683548

- McClungJPKarlJPCableSJRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of iron supplementation in female soldiers during military training: effects on iron status, physical performance, and moodAm J Clin Nutr200990112413119474138

- WHOIron deficiency anemiaAssessment, Prevention and Control A Guide for Programme ManagersGenevaWorld Health Organization2001 Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/ida_assessment_prevention_control.pdfAccessed February 21, 2016

- VerdonFBurnandBStubiCLIron supplementation for unexplained fatigue in non-anaemic women: double blind randomised placebo controlled trialBMJ20033267399112412763985

- LocatelliFAljamaPBaranyPRevised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failureNephrol Dial Transplant200419Suppl 2ii14715206425

- McDonaghTMacdougallICIron therapy for the treatment of iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: intravenous or oral?Eu J Heart Fail2015173248262

- Peyrin-BirouletLWillietNCacoubPGuidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency across indications: a systematic reviewAm J Clin Nutr201510261585159426561626

- SteinJDignassAUManagement of iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease – a practical approachAnn Gastroenterol201326210411324714874

- AuerbachMBallardHClinical use of intravenous iron: administration, efficacy, and safetyHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program2010201033834721239816

- BisbeEGarcia-ErceJADiez-LoboAIMunozMAnemia Working GroupEA multicentre comparative study on the efficacy of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose and iron sucrose for correcting preoperative anaemia in patients undergoing major elective surgeryBr J Anesth20111073477478

- BregmanDBGoodnoughLTExperience with intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in patients with iron deficiency anemiaTher Adv Hematol201452486024688754

- SwissmedicInstitut suisse des produits thérapeutiquesFerinject, solution injectable (carboxymaltose ferrique)2007 Available from: https://www.swissmedic.ch/zulassungen/00153/00189/00200/01057/index.html?lang=frAccessed February 21, 2016

- European Commission – DG Health and Food Safety – Public health EU – Pharmaceutical InformationsListe des noms, des formes pharmaceutiques, du dosage des médicaments, des voies d’administration et des titulaires de l’Autorisation de mise sur le marché dans les Etats membres2013 Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2013/20130913126618/anx_126618_fr.pdfAccessed February 21, 2016

- BeglingerCHBreymannCHTreatment of iron deficiency. Report of practical experience with oral or IV iron replacement preparations [Traitement de la carence en fer. Rapport d’expérience pratique avec des préparations à base de fer administrées par voie orale ou par voie intraveineuse]Forum Med Suisse20107292923927

- RognoniCVenturiniSMeregagliaMMarmiferoMTarriconeREfficacy and safety of ferric carboxymaltose and other formulations in iron-deficient patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsClin Drug Invest2016363177194

- BencaiovaGvon MandachUZimmermannRIron prophylaxis in pregnancy: intravenous route versus oral routeEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2009144213513919406557

- HenryDHDahlNVAuerbachMTchekmedyianSLaufmanLRIntravenous ferric gluconate significantly improves response to epoetin alfa versus oral iron or no iron in anemic patients with cancer receiving chemotherapyOncologist200712223124217296819

- LindgrenSWikmanOBefritsRIntravenous iron sucrose is superior to oral iron sulphate for correcting anaemia and restoring iron stores in IBD patients: A randomized, controlled, evaluator-blind, multicentre studyScan J Gastroenterol2009447838845

- Rozen-ZviBGafter-GviliAPaulMLeiboviciLShpilbergOGafterUIntravenous versus oral iron supplementation for the treatment of anemia in CKD: systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Kidney Dis200852589790618845368

- Van WyckDBMangioneAMorrisonJHadleyPEJehleJAGoodnoughLTLarge-dose intravenous ferric carboxymaltose injection for iron deficiency anemia in heavy uterine bleeding: a randomized, controlled trialTransfusion200949122719272819682342

- FavratBBalckKBreymannCEvaluation of a single dose of ferric carboxymaltose in fatigued, iron-deficient women – PREFER a randomized, placebo-controlled studyPLoS One201494e9421724751822

- ABIM FoundationChoosing wisely2013 Available from: http://www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/Choosing-Wisely.aspxAccessed February 21, 2016

- GarnerSLittlejohnsPDisinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICEly done?BMJ2011343d451921795239

- GlasziouPMoynihanRRichardsTGodleeFToo much medicine; too little careBMJ2013347f424723820022

- Académies suisses des sciences médicalesA sustainable health care system: roadmap of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences [Un système de santé durable pour la Suisse: feuille de route des Académies suisses des sciences médicales]2012 Available from: http://www.academies-suisses.ch/fr/index/Schwerpunktthemen/Gesundheitssystem-im-Wandel/Nachhaltiges-Gesundheitssystem.htmlAccessed February 21, 2016

- GuyattGHOxmanADAliMWillanAMcIlroyWPattersonCLaboratory diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia: an overviewJGIM1992721451531487761

- BeardJLHendricksMKPerezEMMaternal iron deficiency anemia affects postpartum emotions and cognitionJ Nutr2005135226727215671224

- TrenkwalderCHeningWAMontagnaPTreatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practiceMov Disord200823162267230218925578

- GascheCBerstadABefritsRGuidelines on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anemia in inflammatory bowel diseasesInflamm Bowel Dis200713121545155317985376

- GanzoniAMIntravenous iron-dextran: therapeutic and experimental possibilitiesSchweiz Med Wochenschr19701003013035413918

- KillipSBennettJMChambersMDIron deficiency anemiaAm Fam Physician200775567167817375513

- BrunerABJoffeADugganAKCasellaJFBrandtJRandomised study of cognitive effects of iron supplementation in non-anemic iron-deficient adolescent girlsLancet199634890339929968855856

- HaasJDBrownlieTtIron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationshipJ Nutr20011312S–2676S688S discussion 688S–690S11160598

- AnnibaleBCapursoGChistoliniAGastrointestinal causes of refractory iron deficiency anemia in patients without gastrointestinal symptomsAm J Med2001111643944511690568

- WHOAssessing the Iron Status of Populations: Report of a Joint WHO/CDC Technical Consultation on Assessment of Iron Status at the Population Level2004 Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/anaemia_iron_deficiency/9789241596107.pdfAccessed February 21, 2016

- FavratBWaldvogel AbramowskiSVaucherPCornuzJTissotJDIron deficiency without anemia: where are we in 2012?Rev Med Suisse20128364227722782280227123240240

- KulniggSStoinovSSimanenkovVA novel intravenous iron formulation for treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: the ferric carboxymaltose (FERINJECT) randomized controlled trialAm J Gastroenterol200810351182119218371137

- MooreRAGaskellHRosePAllanJMeta-analysis of efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject) from clinical trial reports and published trial dataBMC Blood Disord201111421942989