Abstract

Chronic hepatitis C infection affects millions of people worldwide and confers significant morbidity and mortality. Effective treatment is needed to prevent disease progression and associated complications. Previous treatment options were limited to interferon and ribavirin (RBV) regimens, which gave low cure rates and were associated with unpleasant side effects. The era of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies began with the development of first-generation NS3/4A protease inhibitors in 2011. They vastly improved outcomes for patients, particularly those with genotype 1 infection, the most prevalent genotype globally. Since then, a multitude of DAAs have been licensed for use, and outcomes for patients have improved further, with fewer side effects and cure rates approaching 100%. Recent regimens are interferon-free, and in many cases, RBV-free, and involve a combination of DAA agents. This review summarizes the treatment options currently available and discusses potential barriers that may delay the global eradication of hepatitis C.

Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is estimated to affect up to 177.5 million people worldwide.Citation1 While a small proportion of people clear the virus naturally, chronic hepatitis C (CHC) can lead to a spectrum of liver diseases from mild inflammation with a relatively indolent course to extensive liver fibrosis and consequent cirrhosis, conferring significant morbidity and mortality to affected individuals. With end-stage liver disease, the manifestations of hepatic decompensation are common. Associated hepatocellular carcinoma is a serious complication of CHC-related cirrhosis with an incidence of 5.8% per year in the at-risk population.Citation2 Such disease progression is particularly problematic for CHC patients, as the infection is often asymptomatic and only diagnosed when the pathological processes are relatively advanced.

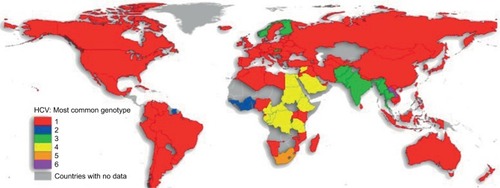

There are six major, structurally different and clinically relevant HCV genotypes, with several subtypes being described.Citation3 In addition, recently, four genotype (GT) 7 patients have been reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo.Citation4 GT1 accounts for the majority of cases worldwide ().Citation5 Distinction between genotypes remains important because treatment regimens are mostly still genotype specific.

Figure 1 Genotype 1 is the most common cause of chronic hepatitis C infection worldwide. Reproduced from Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87. Creative Commons license and disclaimer available from: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.Citation5

Interferon-based regimens, and later with the addition of ribavirin (RBV), were the standard CHC treatment for many years. However, treatment outcomes varied greatly between genotypes, with particularly poor cure rates of 40% being reported in GT1 and GT4 cases.Citation6,Citation7 Since 2011, a number of directly acting antivirals (DAAs) have been licensed for use as part of combination therapies for CHC, and outcomes for patients have improved considerably.

Global distribution of hepatitis C genotypes

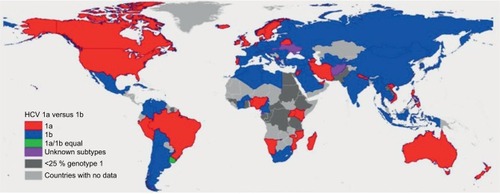

HCV follows a worldwide distribution, with Africa and Central and East Asia being most affected.Citation8 The most common genotype both worldwide and in Europe and North America is GT1, accounting for 49.1% of CHC cases.Citation1 GT1 infection can be further subdivided into two major classes: 1a and 1b.Citation3 While GT1a accounts for the majority of CHC GT1 cases in North America, the majority of CHC GT1 cases worldwide are due to GT1b (68% versus 31% GT1a)Citation5 (). GT3 is the second most common genotype globally, accounting for 17.9% of CHC cases. Worldwide, GT4, GT2, and GT5 account for 16.8%, 11%, and 2% of cases, respectively.Citation1 According to recent estimates, GT6 infection is the least common, accounting for 1.4% of CHC cases.Citation1 Genotype distributions in Europe follow a similar pattern, with GT1 and GT3 accounting for the majority of CHC cases (64.4% and 25.5%, respectively).Citation9 Globally, the majority of GT2 and GT6 cases are found in East Asia. GT4 is most commonly found in North Africa and the Middle East, particularly in Egypt following the anti-schistosomal treatment program that left many millions infected with HCV.Citation5,Citation10 GT5 is primarily found in South Africa.Citation5

Figure 2 Distribution of GT1a versus GT1b. Reproduced from Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87. Creative Commons license and disclaimer available from: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.Citation5

Modes of HCV transmission

Health care-associated transmission, through unsterilized needles or transfusion with contaminated blood, remains a major route of HCV infection, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).Citation10–Citation12 While uncommon in high-income settings, iatrogenic infection has also been reported in European countries including France and Italy,Citation13,Citation14 and in isolated hospital outbreaks in the US.Citation15,Citation16 Indeed, a study of CHC patients in southern Italy showed surgery and dental therapy to be important risk factors for HCV infection.Citation17 People who inject drugs, carrying out high-risk activities such as needle sharing, also account for a significant number of worldwide infections. Principally, this has been the most important factor in the developed world.Citation18 However, more recently, emerging intravenous drug usage in LMICs has been shown as an important vector for HCV transmission.Citation19 Other modes of HCV transmission include vertical mother-to-infant transmission, men who have sex with men, and the increasingly common trend of body art with tattooing.Citation12

HCV structure

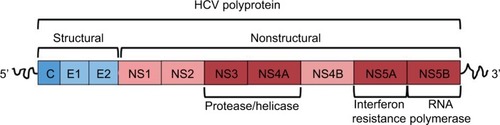

Understanding the structure of HCV is particularly important because newer therapies target specific viral proteins. HCV is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus. Its positively stranded genome encodes a polyprotein, comprising roughly 3,000 amino acids.Citation20 This polyprotein is posttranslationally modified by proteolytic enzymes into four structural and six nonstructural (NS) proteins ().Citation21 Of particular importance are the NS3/4A, NS5A, and NS5B proteins. The NS3/4A serine protease mediates cleavage of the 3,000-amino-acid polyprotein into its respective structural and NS proteins. NS5B is responsible for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity, while NS5A is thought to have a number of roles including mediating interferon resistance.Citation21 Ultimately, these viral proteins work together to drive viral replication and persistence.

Diagnosis of chronic HCV infection

HCV infection may follow an acute or chronic course. Chronic HCV infection is diagnosed based on the presence of anti-HCV antibodies as a screening procedure and quantitative HCV RNA as the definitive test. After 6 months, anti-HCV antibodies are detectable through enzyme immunoassay. HCV RNA is detected using a sensitive molecular method such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with a lower limit of detection of <15 IU/mL.Citation22

The need for treatment

Given the increased morbidity and mortality associated with CHC infection, achieving viral clearance is critical and is associated with significantly reduced rates of liver failure and liver-related deaths amongst CHC patients.Citation23 Viral clearance also significantly reduces fibrosis progression rates and even reverses cirrhosis.Citation24 This explains why risks of all-cause mortality amongst patients with cirrhosis have also been shown to be lower in those successfully clearing the HCV infection.Citation25 Virological clearance of infection with undetectable HCV RNA levels 3–6 months after completing antiviral treatment is termed a sustained virological response (SVR), and this defines a cure.Citation26,Citation27 The concordance of SVR12 (at 12 weeks following end of treatment) and SVR24 (at 24 weeks following end of treatment) as end points of CHC therapy is 99%, meaning that both are acceptable markers of viral clearance.Citation27

Treatment options

Initial treatment options: interferon and RBV

Until the early 1990s, there was no treatment available for CHC. It was during this decade that the benefits of interferon-alfa therapy were reported, leading to a recommended treatment regimen, comprising a 24- or 48-week course of interferon-alfa 2a or 2b, depending on genotype.Citation28 Patients required three times weekly injections, and outcomes were poor, with ≤10% of patients successfully clearing the virus.Citation29 The addition of RBV to interferon-alfa therapy considerably improved outcomes, increasing SVR rates to approximately 30–40%.Citation7

Pegylated interferon and RBV

The development of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-alfa 2a and 2b toward the end of the 1990s altered the kinetics of interferon, meaning that patients only required a single weekly injection.Citation30 It also improved clearance rates and, up until 2011, a 24- or 48-week course of PEG-IFN-alfa 2a or 2b plus RBV was the standard of care for CHC infection.Citation31 SVR rates of up to 80% were reported for GT2, GT3, GT5, and GT6, with GT2 having the highest cure rates.Citation32,Citation33 Intermediate rates of SVR were reported for GT4.Citation33 However, patients with CHC GT1, the most common genotype worldwide, achieved much lower rates of SVR of around 40%.Citation6,Citation7 Rates of SVR were even lower amongst Afro-Caribbean CHC GT1 patients.Citation34 In addition to the variable SVR rates,Citation6,Citation7,Citation32,Citation33 several contraindications meant that PEG-IFN plus RBV therapy was not suitable for a number of patients. Owing to the potential neuropsychiatric effects of interferon, PEG-IFN plus RBV therapy is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled depression or psychosis. Given the immune-modulatory effect of interferon, therapy is contraindicated in patients with autoimmune disease. In individuals with cirrhosis, interferon can precipitate decompensation due to increased necro-inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis. Interferon therapy is thus contraindicated in patients with decompensated liver disease.Citation28 A complete list of contraindications can be found in the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2015 guidelines.Citation32

DAAs: first-generation, “first-wave” protease inhibitors

The poor outcomes reported amongst CHC GT1 patients, who account for the majority of CHC patients worldwide,Citation6,Citation7 drove the need for newer, more effective treatments for CHC infection. The first such drugs to be developed were the protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir (BOC) and telaprevir (TVR). These were first-generation, first-wave DAAs, licensed to treat CHC GT1 infection in 2011.Citation32 Both BOC and TVR are NS3/4A inhibitors. The NS3/4A serine protease plays a key role in HCV replication, cleaving the viral polyprotein into its constituent parts.Citation21 The resultant structural and NS proteins are responsible for viral replication and persistence. By targeting and inhibiting the NS3/4A protease, BOC and TVR are able to mediate viral clearance.Citation20,Citation35 In order to prevent the emergence of viral resistance,Citation36,Citation37 BOC and TVR are given alongside PEG-IFN plus RBV as part of “triple therapy”.

Boceprevir

The antiviral capacity of BOC was first demonstrated in replicon cell modelsCitation38 and later confirmed in phase I and II clinical trials.Citation37,Citation39 The SPRINT-2 phase III trial investigated BOC-based triple therapy amongst CHC GT1 treatment-naïve patients.Citation40 SVR24 rates of 63% (233/368) were reported, compared to 38% (137/363) in patients receiving traditional PEG-IFN plus RBV therapy.Citation40 The RESPOND-2 phase III trial investigated outcomes of CHC GT1 treatment-experienced patients receiving BOC-based triple therapy.Citation41 SVR24 rates of 66% of patients were reported in those receiving 48 weeks of therapy, versus 21% in the PEG-IFN plus RBV control group.Citation41 While achieving higher rates of SVR, BOC therapy was associated with increased frequency of adverse events (AEs). In particular, anemia and dysgeusia were significantly more common in those receiving BOC.Citation40,Citation41

Telaprevir

Early phase I and II clinical trials demonstrated the antiviral capacity of TVR.Citation42–Citation46 The ADVANCE phase III trial investigated TVR-based triple therapy amongst CHC GT1 treatment-naïve patients.Citation47 SVR24 was achieved in 75% (271/363) of TVR patients, versus 44% (158/361) of those receiving traditional therapy.Citation47 The REALIZE phase III trial investigated treatment outcomes of CHC GT1 patients receiving TVR.Citation48 SVR24 rates of 64% in TVR patients, compared to 17% in the control group, were reported.Citation48 As was the case with the other first-wave PI BOC, AEs, especially rash and anemia, were more common in those receiving TVR.Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation48

The problem with first-generation, first-wave PIs – need for alternatives

The first-generation, first-wave NS3/4A PIs BOC and TVR improved outcomes for CHC GT1 patients. SVR rates increased from 40% with traditional interferon-based therapyCitation6,Citation7 to between 64% and 75% using triple therapy with BOC or TVR.Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation48 However, these regimes were limited to CHC GT1, and were associated with frequent side effects including anemia, fatigue, and rash, with consequently high discontinuation rates.Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation48 Dosing regimens were complex, and tablets had to be taken with fatty meals every 8 hours. These complex regimens also conferred drug–drug interactions, complicating coexisting treatments for other conditions. Poorer outcomes were reported in patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis.Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation48 Real-life data reported inferior outcomes, compared to those in phase III trials, with SVR being achieved in 40–53% and 53–56% of BOC and TVR patients, respectively.Citation49,Citation50 Serious AEs were more frequent in real-life treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis receiving BOC/TVR triple therapy.Citation51 Consequently, there was a clear need for more tolerable and effective CHC treatments.

New components to antiviral therapy

Since the release of the first-wave, first-generation PIs BOC and TVR in 2011, there have been a number of DAAs licensed for the treatment of CHC ().

Table 1 Directly acting antivirals and sites of action

NS3/4A inhibitors

Simeprevir

Sharing the same target as its predecessors, BOC and TVR, simeprevir (SMV) is a second-wave, first-generation NS3/4A PI.Citation52 Initial phase I studies demonstrated its antiviral capacity in CHC GT1 patients.Citation53 Subsequent phase II studies confirmed these findings, and also demonstrated antiviral activity in GT2 and GT4–6 patients.Citation54,Citation55

SMV may be given alongside PEG-IFN plus RBV as part of SMV-based triple therapy. This regime was investigated in the QUEST-1 and QUEST-2 phase III clinical trials.Citation56,Citation57 Participants were all treatment-naïve CHC GT1 patients. Eighty percent (210/264) and 81% (209/257) of patients achieved SVR, respectively.Citation56,Citation57 When data from both trials were pooled and analyzed, 85% (228/267) of GT1b patients found to have achieved SVR.Citation32 Outcomes of GT1a patients varied depending on the status of the Q80K polymorphism. This is a naturally occurring polymorphism within the HCV NS3 protease domain, associated with reduced activity of NS3/4A PIs.Citation58 Fifty-eight percent (49/84) of GT1a patients with the Q80K polymorphism and 84% (138/165) of cases without the polymorphism achieved SVR.Citation32 SMV-based triple therapy has also been used to treat CHC GT4 patients. The RESTORE phase III trial investigated outcomes of a mixture of treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced CHC GT4 patients.Citation59 Outcomes were favorable in treatment-naïve and prior relapsers, with 83% (29/35) and 86% (19/22) achieving SVR12, respectively. However, only 60% (6/10) of prior partial responders and 40% (16/40) of prior null responders achieved SVR12.Citation59

Grazoprevir

Grazoprevir (GZR) is a second-generation NS3/4A PI that demonstrates antiviral activity against all major genotypes in vitro.Citation60 GZR triple therapy with PEG-IFN plus RBV in CHC GT1 patients without cirrhosis was investigated in an early phase II study. SVR24 was achieved in 89–93% of patients, depending on the GZR dose received.Citation61 The C-SPIRIT study investigated outcomes of CHC GT1 patients receiving the interferon-free, GZR plus RBV combination.Citation62 Results were good in patients with undetectable HCV RNA 4 weeks into treatment, with 90% (9/10) achieving SVR. However, patients with detectable RNA at week 4 fared less well, with 58% (7/12) achieving SVR.Citation62

Paritaprevir

The final NS3/4A PI licensed for CHC treatment is paritaprevir (PTV). There are limited data regarding PTV therapy with PEG-IFN plus RBV or RBV, as PTV is coadministered with other antiviral agents.

Asunaprevir, voxileprevir, and glecaprevir

Asunaprevir (ASN), voxileprevir (VOX), and glecaprevir (GLC) are some of the last remaining NS3/4A PIs in development. There are limited data regarding ASN/VOX/GLC therapy with PEG-IFN plus RBV or RBV, as these PIs are given alongside other DAAs. Phase III trial data show ASN in combination with other DAAs to be an effective treatment for patients with cirrhosis and GT1 infection.Citation63 Phase II data has demonstrated promising outcomes for GT1 and GT3 patients treated with VOX- or GLC-based DAA regimes.Citation64,Citation65 We await the results of phase III trial data to confirm these findings.

NS5A inhibitors

Daclatasvir

Daclatasvir (DCV) is a pangenotypic NS5A inhibitor. The HCV NS5A protease has a number of roles essential for viral replication, including mediating interferon-resistance, thereby precipitating viral persistence.Citation21 Thus, targeting and inhibiting the NS5A protease offers a potential route of viral clearance. The antiviral capacity of DCV in GT1 patients was demonstrated in an early phase II study, where it was given alongside PEG-IFN plus RBV as part of DCV-based triple therapy.Citation66 A subsequent phase II study confirmed the efficacy of DCV-based triple therapy in CHC GT1 patients, and also added to previous findings by demonstrating effectiveness amongst GT4 patients.Citation67 Phase III clinical trials investigating DCV-based triple therapy are yet to be done, as recent research is focused on combining DCV with other DAAs.

Ledipasvir, elbasvir, ombitasvir, velpatasvir, and odalasvir

Ledipasvir (LDV), elbasvir (EBR), ombitasvir (OBV), velpatasvir (VEL), and odalasvir are all NS5A inhibitors with varying genotype activity, particularly against GT1 and GT4 infection. Demonstrating antiviral activity in early studies,Citation68–Citation71 these NS5A inhibitors are given in combination with a variety of other DAAs.

NS5B inhibitors

Sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir (SOF) is a pangenotypic nucleotide analog inhibitor of HCV NS5B viral polymerase. The HCV NS5B polymerase is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which facilitates RNA synthesis during HCV replication.Citation72 Therefore, inhibition of the HCV NS5B polymerase offers significant antiviral potential. As with other DAAs, SOF may be given alongside PEG-IFN plus RBV as part of SOF-based triple therapy. While SMV is only used for CHC GT1 and GT4 patients, SOF demonstrates pangenotypic antiviral activity in vitroCitation72 which has been confirmed in subsequent clinical trials.Citation73–Citation75

The NEUTRINO phase III trial investigated outcomes of SOF-based triple therapy amongst treatment-naïve CHC GT1 and GT4–6 patients.Citation73 Of the 327 patients included, 291 (89%) were infected with GT1 (225 GT1a and 66 GT1b), 28 (9%) with GT4, one with GT5 (1%), and six with GT6 (6%). SVR was achieved in 89% (259/291) of CHC GT1 patients. Within those infected with GT1 subtypes, SVR was achieved in 92% (207/225) and 82% (54/66) of GT1a and GT1b patients, respectively. Ninety-six percent (27/28) of GT4 patients achieved SVR. Both the single GT5 patient and six GT6 patients achieved SVR.Citation73

SOF-based triple therapy has also been shown to be effective in CHC GT2 and GT3 patients. In a phase II study of 23 treatment-experienced GT2 patients, 96% achieved SVR.Citation75 This study also investigated outcomes of GT3 patients, with 83% (20/24) patients achieving SVR.Citation75 The effectiveness of SOF-based triple therapy in CHC GT3 was confirmed in a second phase II study, where nine of 10 treatment-naïve CHC GT3 patients achieved SVR.Citation74 The remaining patient was lost to follow-up. Phase III trials investigating this regime have yet to be published at the time of writing.

SOF may also be given with RBV as part of an interferon-free regime. This combination has been used in the treatment of GT2–4 infection. Phase III trials involving GT2 patients reported SVR rates between 86% and 97% following a 12-week course of SOF plus RBV.Citation73,Citation76,Citation77 These phase III trials also investigated outcomes of GT3 patients treated with SOF plus RBV. The FISSION and POSITRON trials reported SVR rates of 56% (102/183) and 61% (60/98), respectively, with a 12-week course of SOF plus RBV.Citation73,Citation76 The FUSION trialCitation76 compared outcomes of 12-week versus 16-week SOF plus RBV therapy amongst GT3 patients, and found longer treatment duration to be associated with higher rates of SVR (30% versus 62%, respectively). As a result of these findings, the VALENCE trial increased treatment duration to 24 weeks, and reported SVR rates of 85% (213/250) amongst GT3 patients.Citation77 Trials involving Egyptian patients with GT4 infection treated for 12 and 24 weeks with SOF plus RBV reported SVR rates of 68–77% and 90–93%, respectively.Citation78,Citation79

The combination of SOF plus RBV was well tolerated, with few patients stopping treatment due to side effects. GT2 and GT4 patients achieved high rates of SVR, and while rates of SVR were lower amongst GT3 patients, outcomes were improved with longer treatment durations.Citation73,Citation76–Citation79

Dasabuvir

Dasabuvir (DVR) is a non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor.Citation80 This DAA is given in combination with other DAAs to mediate viral clearance, and has been shown to be particularly effective in treating CHC GT1.Citation81–Citation83

The dawn of interferon-free regimes

The addition of DAAs to PEG-IFN plus RBV as part of triple therapy vastly improved outcomes for patients with CHC. Superior rates of SVR were reported, alongside shortened treatment durations for certain cohorts. However, triple therapy still involved interferon as a mainstay of treatment, bringing with it unpleasant side effects and weekly injections. These factors led to the development of new interferon-free regimens, combining various DAAs, with or without RBV. Interferon-free regimens vary depending on genotype and presence of cirrhosis, and are summarized in . Those interferon-free regimes currently licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the US are described in the review by Zhang et al.Citation84

Table 2 Interferon-free treatment regimens for chronic hepatitis C according to cirrhosis and treatment status, as recommended by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and AASLD

SOF and LDV

The combination of NS5B inhibitor SOF plus NS5A inhibitor LDV (SOF/LDV) is recommended for use in GT1 and GT4–6 patients.Citation22 SOF/LDV therapy has been shown to be highly effective in treating GT1 patients, with phase III trials reporting rates of SVR between 94% and 99% in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced GT1 patients treated with or without RBV for 12 weeks.Citation85–Citation87 Findings of the ION-3 phase III trial suggested that RBV-free SOF/LDV treatment could be shortened to 8 weeks, but future real-life work is needed to confirm these findings, as no patients with cirrhosis were included in the study.Citation87 Post hoc analysis suggested that a viral load of <6,000,000 IU/mL should be the cut-off value when 8-week therapy is used.Citation88 However, because HCV RNA level determination may be inaccurate at these values, there is still uncertainty as to whether patients with viral loads of <6,000,000 IU/mL should receive 8- or 12-week SOF/LDV.Citation89 Current guidelines recommend the addition of RBV, or extending treatment duration to 24 weeks (without RBV), for patients with negative predictors of response, such as cirrhosis, or those who have failed previous treatment.Citation22

Trial data have shown SOF/LDV without RBV to be effective in the treatment of GT4 infection, with 95% (20/21) of patients achieving SVR.Citation90 This regimen has also been shown effective in GT6 patients, with 96% (24/25) achieving SVR.Citation91 Most recently, a phase II trial involving GT5 patients reported SVR rates of 95% (39/41) in those receiving SOF/LDV without RBV.Citation92

Ritonavir-boosted PTV and OBV with or without DVR

This combination of DAAs has been shown to be effective in treating GT1 and GT4 infection. PTV, OBV, and DVR are DAAs targeting the NS3/4A, NS5A, and NS5B HCV proteases, respectively. Ritonavir is an inhibitor of the cytochrome (CYP) P450 enzyme CYP3A4, and acts as a pharmacological enhancer of PTV, allowing for once-daily dosing.Citation93 Phase III trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of ritonavir-boosted PTV/OBV/DVR in the treatment of GT1 infection. Amongst treatment-naïve patients, SVR rates between 90% and 99% were reported, depending on genotype subtype and addition of RBV to treatment regime.Citation81,Citation82 SVR rates between 96% and 100% have been reported in phase III trials involving treatment-experienced patients.Citation83,Citation94 Finally, the TURQUOISE phase III trial reported rates of SVR of 92% (191/208) and 96% (165/172) in patients with cirrhosis receiving 12- and 24-week treatment with PTV/OBV/DVR plus RBV, respectively.Citation95

The use of a 12-week regimen of ritonavir-boosted PTV/OBV with RBV (without DVR) in treating GT4 infection is studied in the PEARL-1, AGATE-1, and AGATE-2 trials.Citation96–Citation98 In the PEARL-1 trial, a total of 91 treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients without cirrhosis received this treatment regimen. All 91 achieved SVR12.Citation96 The AGATE-1 and AGATE-2 trials added to findings of the PEARL-1 study by including patients with cirrhosis. All study participants in the AGATE-1 trial had cirrhosis, where SVR rates of 97% (59/61) were reported.Citation97 The AGATE-2 trial investigated patients with and without cirrhosis. SVR rates of 97% (30/31) and 94% (94/100) were achieved in these cohorts, respectively. Extending treatment duration to 24 weeks did not increase rates of SVR in a sub-cohort of patients with cirrhosis.Citation98

SOF and SMV

The RBV-free combination of NS5B inhibitor SOF and NS3/4A inhibitor SMV has been shown to be effective in treating GT1 and GT4 infection. The OPTIMIST-1Citation99 and OPTIMIST-2Citation100 phase III trials investigated outcomes of GT1-infected patients without and with cirrhosis, respectively. Rates of SVR were 97% (150/155) in patients without cirrhosis receiving 12-week treatment with SOF/SMV.Citation99 SVR rates were 83% (86/103) in patients with cirrhosis receiving this treatment regimen.Citation100 In keeping with existing literature,Citation58 the presence of the Q80K polymorphism amongst GT1a patients was associated with lower rates of SVR.Citation100

SOF and DCV

The use of SOF/DCV with or without RBV has been shown to be effective in treating GT1 and GT2 infection. In a phase II trial, SVR was achieved in 98% (164/167) and 92% (24/26) of GT1 and GT2 patients, respectively.Citation101 This combination has also been shown effective in treating GT3 infection, with an SVR rate of 89% reported in a phase II (16/18)Citation101 and phase III (135/152) trial.Citation102

SOF and VEL

The once-daily, RBV-free combination of SOF/VEL has been shown to be an effective pangenotypic therapeutic option. The ASTRAL-1Citation103 phase III trial investigated outcomes of patients with GT1, GT2, or GT4–6 infection. GT1 patients achieved SVR rates of 98% (323/328), including 98% (206/210) and 99% (117/118) in patients with GT1a or 1b infection, respectively. SVR rates of 100% (104/104), 100% (116/116), 97% (34/35), and 100% (41/41) were reported in patients with GT2, GT4, GT5, and GT6 infection, respectively.Citation103 The ASTRAL-2 and ASTRAL-3 phase III trials investigated outcomes of GT2 and GT3 patients. Confirming findings of the ASTRAL-1 phase III trial, 99% (133/134) of GT2 patients achieved SVR.Citation103,Citation104 GT3 SVR rates were 95% (264/277), but patients with NS5A resistance-associated variants achieved lower rates of SVR.Citation104

GZR and EBR

The RBV-free combination of GRZ/EBR has been shown to be effective in treating GT1, GT4, and GT6. The C-WORTHY phase II trial investigated outcomes of GT1 patients. Following a 12-week regimen with GRZ/EBR, SVR rates of 92% (48/52) and 95% (21/22) were reported in GT1a and GT1b patients, respectively.Citation105 These findings were confirmed in the subsequent C-EDGE phase III trial, where 92% (144/157) of GT1a and 99% (129/131) of GT1b patients achieved SVR.Citation106 The presence of certain NS5A resistance-associated variants was associated with lower responsiveness to therapy.Citation106 There are limited data for outcomes of non-GT1 patients. The C-EDGE phase III trial also included GT4 and GT6 patients. SVR was achieved in 100% (18/18) and 80% (8/10) of patients, respectively.Citation106 Ideally, further work involving larger patient cohorts is needed to confirm the efficacy of GZR/EBR for GT4/GT6 infection.

Looking ahead: pangenotypic therapies

The past 25 years have seen a revolutionary change in the treatment of CHC. The discovery of DAAs vastly improved cure rates, with certain combinations curing HCV infection in almost 100% of cases. Once-daily, oral combinations have superseded interferon-based regimens, which were associated with complex dosing schedules, weekly injections, and unpleasant side effects. Treatment duration has also been shortened considerably, reducing side-effect profiles and making treatment regimes more bearable. Ultimately, what was once an incurable disease is now potentially curable in almost all those who are able to access the new standards of care.

In June 2016, the first fixed-dose combination pangenotypic regimen of SOF/VEL was approved by the FDA,Citation107 heralding a new era of DAA therapy with an almost “one-size-fits-all”-type management and potentially simplifying management by obviating the need to determine genotype prior to treatment. The ASTRAL-1–5 studies have confirmed the pangenotypic efficacy of SOF/VEL, as well as its effi-cacy in HIV/HCV coinfection and decompensated liver disease.Citation103,Citation104,Citation108,Citation109 There is also the desire to reduce treatment durations even further, and it will likely be investigated in future work.

An important factor influencing DAA therapy is drug–drug interactions (especially with antiretrovirals) that alter DAA efficacy through pharmacokinetic interactions as a result of enzyme induction or inhibition of the CYP P450 enzyme subunits involved in the metabolism of DAAs. All potential drug–drug interactions must be checked before initiation of DAA therapy (http://www.hep-druginteractions.org).

One potential alternative method of pangenotypic therapy involves host-targeted agents (HTAs). Rather than targeting the virus directly like DAAs, HTAs act on the host, interfering with cellular factors involved in viral replication.Citation110 One such target for HTAs is the hepatic microRNA-122 (miRNA-122), which binds to the HCV genome and enhances viral replication.Citation111 The modified oligonucleotide, Miravirsen, sequesters and inhibits miRNA-122, and has been shown to reduce HCV RNA levels in a human phase II trial.Citation112 More recently, another miRNA-122 inhibitor, RG-101, has been shown as a potentially valuable addition to HCV treatment. By adding RG-101 to DAA-based therapy, treatment duration was shortened to 4 weeks. At interim analysis, 97% (37/38) of patients achieved SVR at 8 weeks after completing treatment.Citation113

By targeting host factors with low genetic variability, HTAs offer a high genetic barrier to resistance.Citation110 This is in contrast to DAAs, where resistance may emerge due to the high levels of viral genetic heterogeneity. Consequently, it is thought that the combination of HTAs with DAAs may prevent the emergence resistance, potentially allowing for even shorter treatment periods.Citation114 Initial experiences with HTAs such as RG-101 are encouraging,Citation113 but we await the results of phase III trials to confirm these findings.

Potential barriers to HCV eradication, and possible solutions

With the emergence of therapies able to cure HCV in almost all instances, the World Health Organization (WHO) has prioritized global elimination by 2030 as part of their sustainable development goals.Citation115 However, in order to achieve this, there are a number of barriers to eradication that must be overcome.

Therapeutic barriers

One such barrier is the prohibitive cost of DAAs. The latest generation of DAAs is expensive, and there is significant variation in DAA costs between countries.Citation116 For example, a 12-week course of SOF costs around £35,000 in the UK, and $84,000 (roughly £55,000 GBP) in the US.Citation117 With many countries being limited by finite financial health care resources, these latest, highly efficacious treatments will not be available to everyone. A mechanism of approaching this problem is through treatment prioritization: those who will benefit the most are treated first. However, while treatment prioritization may be a means to manage finite health care resources, it should be accepted that all with CHC warrant therapy and should be treated, except those with an obvious reason not to do so, such as terminal end-stage disease.Citation22 One such criterion for treatment prioritization is the degree of fibrosis, including presence of cirrhosis. While liver biopsy and transient elastography are commonly used to assess the degree of liver fibrosis, these tests are expensive and require specialist health care settings and equipment, limiting their use in LMICs. Portable transient elastography offers a cheaper alternative to its fixed counterpart, but with devices costing US$30,000 plus annual maintenance costs of US$4,700, the use of portable transient elastography may not be feasible in many LMICs.Citation118 Noninvasive serum-based tests like the aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI) and FIB-4 measure indirect markers of fibrosis such as alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and platelets. The WHO, in its HCV guidelines, recommends the use of such scoring systems in resource-limited settings as an amenable method of disease stratification.Citation118

Generic licensing offers an attractive means to upscale therapy. This allows for generic drugs to be manufactured, which are equivalent to “brand drugs” in dosage, strength, route of administration, quality, performance, and intended use.Citation119 The advantage of using generic drugs is that they are much cheaper than the originator products. This is particularly advantageous for less economically developed countries where there is less money available for expensive treatments. Generic SOF, SOF/LDV, and DCV are being manufactured under license to the originator companies by pharmaceutical companies in India. Gilead have licensed 11 generic manufacturers in India to allow distribution to 101 countries globally.Citation120 In April 2015, the WHO included DCV in its essential medicine list, and in November 2015, Bristol-Myers Squibb allowed the Medicines Patent Pool to pronounce a license and technology transfer agreement for DCV in 112 LMICs allowing for manufacturing of generic DCV globally.Citation121

One final way of addressing the issue of expensive treatment is through government subsidization. The Japanese Government heavily subsidized the cost of SOF for patients treated under the national health plan. This means that for every patient treated with a 12-week course of SOF, the government will pay US$43,000, and the patient US$335.Citation122 Following the mass anti-schistosomal treatment regime that left millions chronically infected with HCV,Citation10 the Egyptian government is now also subsidizing treatment.Citation123 Egypt has gone a step further and is producing its own generic SOF and DCV. Similar governmental subsidization schemes are also offered in Australia.Citation124

Diagnostic barriers

A significant challenge facing HCV eradication is that many patients are unaware of their infection. If patients do not know they are infected, then treatment, no matter how effective, will not be administered. This is particularly problematic in LMICs, where the vast proportion of CHC cases are found.Citation5 Furthermore, it is imperative to have an idea of the scale of HCV infection before implementing a successful global health intervention. Screening is recommended in at-risk populations, and is based on the detection of anti-HCV antibodies using enzyme immunoassays.Citation22 HCV RNA detection is then carried out using PCR to identify viremic patients and monitor treatment progress.Citation22 However, such screening tools may not be applicable in LMICs, as they require laboratories with sophisticated equipment and trained staff. When present, such laboratories are often few in number and centralized, limiting access to screening. In addition, even where screening is readily available, the associated financial costs borne by the patient are much higher than in Europe or North America.Citation125 Finally, transportation of blood samples to centralized laboratories may be associated with logistical issues, meaning that patients must travel to a clinic nearby in order to be screened.Citation125

One alternative to the expensive and complex PCR-based testing involves HCV core-antigen detection. HCV core-antigen levels correlate with HCV RNA levels, thus acting as a surrogate marker of HCV replication.Citation126 While highly accurate at diagnosing HCV infection, core-antigen detection is not suitable for determining response-guided therapies, owing to its relative insensitivity at low viral loads.Citation127 Nevertheless, LMICs may benefit from the incorporation of core-antigen testing for HCV screening and disease monitoring.

The recent development of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) offers an attractive solution to the problems associated with blood collection and transport. RDTs test for infection using blood serum or plasma, or oral fluid.Citation128 The major advantage is that they are simple, offer rapid results at room temperature, and require very little training to use.Citation128 One such example is the use of dried blood spot (DBS) samples. These involve dried spots of capillary samples collected on filter paper. DBS testing has been shown highly sensitive in detecting anti-HCV antibodies, but relatively insensitive at measuring HCV RNA and core-antigen levels.Citation128–Citation130 Although genotyping is not always possible with DBS testing,Citation129 this is unlikely to matter, as the latest SOF-based regimens offer pangenotype coverage. RDT using oral fluid samples as an alternative to DBS has also been shown effective at detecting anti-HCV antibodies.Citation130

Conclusion

Treatment for CHC has advanced significantly in the last few years. What was once a lifelong condition requiring complex, relatively ineffective treatment regimens with unpleasant side effects can now be cured in almost all instances with a short course of once-daily, all-oral medication, with an SVR associated with an improvement in all-cause and liver-related mortality.Citation23–Citation25 Thus, all HCV-infected individuals are candidates for treatment, but in resource-constrained countries with a backlog of untreated, HCV-infected individuals, treatment will need to be prioritized. In high-risk groups at risk of reinfection, strategies aimed at behavior modification and harm reduction will be important. While there are still barriers preventing the complete eradication of CHC, shared international efforts to overcome these give cause to be optimistic of what the future of CHC treatment holds.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge the support of the Wellcome Global Centre at Imperial College London for financial and logistic support and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College London for infrastructure support.

Disclosure

SDT-R holds grants from the UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (London, UK). The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PetruzzielloAMariglianoSLoquercioGCozzolinoACacciapuotiCGlobal epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: an up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypesWorld J Gastroenterol201622347824784027678366

- ButDYLaiCLYuenMFNatural history of hepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinomaWorld J Gastroenterol200814111652165618350595

- SmithDBBukhJKuikenCExpanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resourceHepatology201459131832724115039

- MurphyDGSablonEChamberlandJFournierEDandavinoRTremblayCLHepatitis C virus genotype 7, a new genotype originating from central AfricaJ Clin Microbiol201553396797225520447

- MessinaJPHumphreysIFlaxmanAGlobal distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypesHepatology2015611778725069599

- FriedMWShiffmanMLReddyKRPeginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infectionN Engl J Med20023471397598212324553

- McHutchisonJGGordonSCSchiffERInterferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy GroupN Engl J Med199833921148514929819446

- World Health OrganizationHepatitis C: WHO fact sheet Updated July 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/Accessed August 13, 2016

- PetruzzielloAMariglianoSLoquercioGCacciapuotiCHepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes distribution: an epidemiological up-date in EuropeInfect Agent Cancer2016115327752280

- FrankCMohamedMKStricklandGTThe role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in EgyptLancet2000355920788789110752705

- EzeJCIbeziakoNSIkefunaANNwokoyeICUleanyaNDIlechukwuGCPrevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection among children in Enugu, NigeriaAfr J Infect Dis2014815824653810

- LaniniSEasterbrookPJZumlaAIppolitoGHepatitis C: global epidemiology and strategies for controlClin Microbiol Infect2016221083383827521803

- de LédinghenVTrimouletPCazajousGEpidemiological and phylogenetic evidence for patient-to-patient hepatitis C virus transmission during sclerotherapy of varicose veinsJ Med Virol200576227928415834864

- LaniniSAbbateIPuroVMolecular epidemiology of a hepatitis C virus epidemic in a haemodialysis unit: outbreak investigation and infection outcomeBMC Infect Dis20101025720799943

- MooreZSSchaeferMKHoffmannKKTransmission of hepatitis C virus during myocardial perfusion imaging in an outpatient clinicAm J Cardiol2011108112613221529725

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Acute hepatitis C virus infections attributed to unsafe injection practices at an endoscopy clinic–Nevada, 2007MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2008571951351718480743

- PetruzzielloACoppolaNLoquercioGDistribution pattern of hepatitis C virus genotypes and correlation with viral load and risk factors in chronic positive patientsIntervirology201457631131825170801

- RutaSCernescuCInjecting drug use: a vector for the introduction of new hepatitis C virus genotypesWorld J Gastroenterol20152138108111082326478672

- SolomonSSSrikrishnanAKMcFallAMBurden of liver disease among community-based people who inject drugs (PWID) in Chennai, IndiaPLoS One2016111e014787926812065

- McGovernBHAbu DayyehBKChungRTAvoiding therapeutic pitfalls: the rational use of specifically targeted agents against hepatitis C infectionHepatology20084851700171218972443

- BlightKJKolykhalovAAReedKEAgapovEVRiceCMMolecular virology of hepatitis C virus: an update with respect to potential antiviral targetsAntivir Ther19983Suppl 3718110726057

- European Association for the Study of the LiverEASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2016J Hepatol201766115319427667367

- VeldtBJHeathcoteEJWedemeyerHSustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosisAnn Intern Med20071471067768418025443

- PoynardTMcHutchisonJMannsMImpact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis CGastroenterology200212251303131311984517

- van der MeerAJVeldtBJFeldJJAssociation between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosisJAMA2012308242584259323268517

- SwainMGLaiMYShiffmanMLA sustained virologic response is durable in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirinGastroenterology201013951593160120637202

- Martinot-PeignouxMSternCMaylinSTwelve weeks posttreatment follow-up is as relevant as 24 weeks to determine the sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C virus receiving pegylated interferon and ribavirinHepatology20105141122112620069649

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel statement: management of hepatitis CHepatology1997263 Suppl 12S10S9305656

- CarithersRLJrEmersonSSTherapy of hepatitis C: meta-analysis of interferon alfa-2b trialsHepatology1997263 Suppl 183S88S9305670

- Di BisceglieAMHoofnagleJHOptimal therapy of hepatitis CHepatology2002365 Suppl 1S121S12712407585

- European Association for the Study of the LiverEASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infectionJ Hepatol201155224526421371579

- European Association for Study of LiverEASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2015J Hepatol201563119923625911336

- AntakiNCraxiAKamalSThe neglected hepatitis C virus genotypes 4, 5 and 6: an international consensus reportLiver Int201030334235520015149

- MuirAJBornsteinJDKillenbergPGAtlantic Coast Hepatitis Treatment GroupPeginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-Hispanic whitesN Engl J Med2004350222265227115163776

- MoralesJMFabriziFHepatitis C and its impact on renal transplantationNat Rev Nephrol201511317218225643666

- KiefferTLSarrazinCMillerJSTelaprevir and pegylated interferon-alpha-2a inhibit wild-type and resistant genotype 1 hepatitis C virus replication in patientsHepatology200746363163917680654

- SarrazinCRouzierRWagnerFSCH 503034, a novel hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor, plus pegylated interferon alpha-2b for genotype 1 nonrespondersGastroenterology200713241270127817408662

- MalcolmBALiuRLahserFSCH 503034, a mechanism-based inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease, suppresses polyprotein maturation and enhances the antiviral activity of alpha interferon in replicon cellsAntimicrob Agents Chemother20065031013102016495264

- KwoPYLawitzEJMcConeJSPRINT-1 investigatorsEfficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trialLancet2010376974270571620692693

- PoordadFMcConeJJrBaconBRSPRINT-2 InvestigatorsBoceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131195120621449783

- BaconBRGordonSCLawitzEHCV RESPOND-2 InvestigatorsBoceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131207121721449784

- ReesinkHWZeuzemSWeeginkCJRapid decline of viral RNA in hepatitis C patients treated with VX-950: a phase Ib, placebo-controlled, randomized studyGastroenterology20061314997100217030169

- LawitzERodriguez-TorresMMuirAJAntiviral effects and safety of telaprevir, peginterferon alfa-2a, and ribavirin for 28 days in hepatitis C patientsJ Hepatol200849216316918486984

- ForestierNReesinkHWWeeginkCJAntiviral activity of telaprevir (VX-950) and peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with hepatitis CHepatology200746364064817879366

- McHutchisonJGEversonGTGordonSCPROVE1 Study TeamTelaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2009360181827183819403902

- HézodeCForestierNDusheikoGPROVE2 Study TeamTelaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infectionN Engl J Med2009360181839185019403903

- JacobsonIMMcHutchisonJGDusheikoGADVANCE Study TeamTelaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infectionN Engl J Med2011364252405241621696307

- ZeuzemSAndreonePPolSREALIZE Study TeamTelaprevir for retreatment of HCV infectionN Engl J Med2011364252417242821696308

- PriceJCMurphyRCShvachkoVAPaulyMPManosMMEffectiveness of telaprevir and boceprevir triple therapy for patients with hepatitis C virus infection in a large integrated care settingDig Dis Sci201459123043305225102983

- VoKPVutienPAkiyamaMJPoor sustained virological response in a multicenter real-life cohort of chronic hepatitis C patients treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin plus telaprevir or boceprevirDig Dis Sci20156041045105125821099

- HézodeCFontaineHDorivalCCUPIC Study GroupTriple therapy in treatment-experienced patients with HCV-cirrhosis in a multicentre cohort of the French Early Access Programme (ANRS CO20-CUPIC) - NCT01514890J Hepatol201359343444123669289

- LinTILenzOFanningGIn vitro activity and preclinical profile of TMC435350, a potent hepatitis C virus protease inhibitorAntimicrob Agents Chemother20095341377138519171797

- ReesinkHWFanningGCFarhaKARapid HCV-RNA decline with once daily TMC435: a phase I study in healthy volunteers and hepatitis C patientsGastroenterology2010138391392119852962

- FriedMWButiMDoreGJOnce-daily simeprevir (TMC435) with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in treatment-naïve genotype 1 hepatitis C: the randomized PILLAR studyHepatology20135861918192923907700

- MorenoCBergTTanwandeeTAntiviral activity of TMC435 monotherapy in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2-6: TMC435-C202, a phase IIa, open-label studyJ Hepatol20125661247125322326470

- JacobsonIMDoreGJFosterGRSimeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2014384994140341324907225

- MannsMMarcellinPPoordadFSimeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trialLancet2014384994141442624907224

- SarrazinCLathouwersEPeetersMPrevalence of the hepatitis C virus NS3 polymorphism Q80K in genotype 1 patients in the European regionAntiviral Res2015116101625614456

- MorenoCHezodeCMarcellinPEfficacy and safety of simeprevir with PegIFN/ribavirin in naïve or experienced patients infected with chronic HCV genotype 4J Hepatol20156251047105525596313

- SummaVLudmererSWMcCauleyJAMK-5172, a selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease with broad activity across genotypes and resistant variantsAntimicrob Agents Chemother20125684161416722615282

- MannsMPVierlingJMBaconBRThe combination of MK-5172, peginterferon, and ribavirin is effective in treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection without cirrhosisGastroenterology20141472366376.e624727022

- GaneEBen AriZMollisonLEfficacy and safety of grazoprevir + ribavirin for 12 or 24 weeks in treatment-naïve patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infectionJ Viral Hepat2016231078979727291249

- MuirAJPoordadFLalezariJDaclatasvir in combination with asunaprevir and beclabuvir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection with compensated cirrhosisJAMA2015313171736174425942724

- GaneEPoordadFWangSHigh efficacy of ABT-493 and ABT-530 treatment in patients with HCV genotype 1 or 3 infection and compensated cirrhosisGastroenterology20161514651659.e127456384

- GaneEJSchwabeCHylandRHEfficacy of the combination of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and the NS3/4A protease inhibitor GS-9857 in treatment-naïve or previously treated patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 3 infectionsGastroenterology20161513448456.e127240903

- PolSGhalibRHRustgiVKDaclatasvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C genotype-1 infection: a randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 2a trialLancet Infect Dis201212967167722714001

- HézodeCHirschfieldGMGhesquiereWDaclatasvir plus peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for treatment-naive chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 or 4 infection: a randomised studyGut201564694895625080450

- LinkJOTaylorJGXuLDiscovery of ledipasvir (GS-5885): a potent, once-daily oral NS5A inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infectionJ Med Chem20145752033204624320933

- CoburnCAMeinkePTChangWDiscovery of MK-8742: an HCV NS5A inhibitor with broad genotype activityChemMedChem20138121930194024127258

- KowdleyKVLawitzEPoordadFPhase 2b trial of interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C virus genotype 1N Engl J Med2014370322223224428468

- LawitzEFreilichBLinkJA phase 1, randomized, dose-ranging study of GS-5816, a once-daily NS5A inhibitor, in patients with genotype 1-4 hepatitis C virusJ Viral Hepat201522121011101926183611

- LamAMMurakamiEEspirituCPSI-7851, a pronucleotide of beta-D-2¢-deoxy-2¢-fluoro-2¢-C-methyluridine monophosphate, is a potent and pan-genotype inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replicationAntimicrob Agents Chemother20105483187319620516278

- LawitzEMangiaAWylesDSofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infectionN Engl J Med2013368201878188723607594

- LawitzELalezariJPHassaneinTSofosbuvir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for non-cirrhotic, treatment-naive patients with genotypes 1, 2, and 3 hepatitis C infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trialLancet Infect Dis201313540140823499158

- LawitzEPoordadFBrainardDMSofosbuvir with peginterferon-ribavirin for 12 weeks in previously treated patients with hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 and cirrhosisHepatology201561376977525322962

- JacobsonIMGordonSCKowdleyKVPOSITRON StudyFUSION StudySofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment optionsN Engl J Med2013368201867187723607593

- ZeuzemSDusheikoGMSalupereRVALENCE InvestigatorsSofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3N Engl J Med2014370211993200124795201

- RuanePJAinDStrykerRSofosbuvir plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic genotype 4 hepatitis C virus infection in patients of Egyptian ancestryJ Hepatol20156251040104625450208

- DossWShihaGHassanyMSofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treating Egyptian patients with hepatitis C genotype 4J Hepatol201563358158525937436

- MantryPSPathakLDasabuvir (ABT333) for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype I: a new face of cure, an expert reviewExpert Rev Anti Infect Ther201614215716526567871

- FeldJJKowdleyKVCoakleyETreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirinN Engl J Med2014370171594160324720703

- FerenciPBernsteinDLalezariJPEARL-III StudyPEARL-IV StudyABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCVN Engl J Med2014370211983199224795200

- ZeuzemSJacobsonIMBaykalTRetreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirinN Engl J Med2014370171604161424720679

- ZhangJNguyenDHuKQChronic hepatitis C virus infection: a review of current direct-acting antiviral treatment strategiesN Am J Med Sci (Boston)201692475427293521

- AfdhalNReddyKRNelsonDRION-2 InvestigatorsLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2014370161483149324725238

- AfdhalNZeuzemSKwoPION-1 InvestigatorsLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2014370201889189824725239

- KowdleyKVGordonSCReddyKRION-3 InvestigatorsLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosisN Engl J Med2014370201879188824720702

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and ResearchSofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination. Statistical Review and Evaluation, NDA 205834 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/205834Orig1s000MedR.pdfAccessed 12 November, 2016

- VermehrenJMaasoumyBMaanRApplicability of hepatitis C virus RNA viral load thresholds for 8-week treatments in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infectionClin Infect Dis201662101228123426908802

- KohliAKapoorRSimsZLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 4: a proof-of-concept, single-centre, open-label phase 2a cohort studyLancet Infect Dis20151591049105426187031

- GaneEJHylandRHAnDHigh efficacy of LDV/SOF regimens for 12 weeks for patients with HCV genotype 3 or 6 infectionHepatology20146061274A1275A

- AbergelAAsselahTMetivierSLedipasvir-sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 5 infection: an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 studyLancet Infect Dis201616445946426803446

- BrayerSWReddyKRRitonavir-boosted protease inhibitor based therapy: a new strategy in chronic hepatitis C therapyExpert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol20159554755825846301

- AndreonePColomboMGEnejosaJVABT-450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infectionGastroenterology20141472359365.e124818763

- PoordadFHezodeCTrinhRABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosisN Engl J Med2014370211973198224725237

- HézodeCAsselahTReddyKROmbitasvir plus paritaprevir plus ritonavir with or without ribavirin in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C virus infection (PEARL-I): a randomised, open-label trialLancet201538599862502250925837829

- AsselahTHézodeCQaqishRBOmbitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir plus ribavirin in adults with hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection and cirrhosis (AGATE-I): a multicentre, phase 3, randomised open-label trialLancet Gastroenterol Hepatol2016112535

- WakedIShihaGQaqishRBOmbitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection in Egyptian patients with or without compensated cirrhosis (AGATE-II): a multicentre, phase 3, partly randomised open-label trialLancet Gastroenterol Hepatol2016113644

- KwoPGitlinNNahassRSimeprevir plus sofosbuvir (12 and 8 weeks) in hepatitis C virus genotype 1-infected patients without cirrhosis: OPTIMIST-1, a phase 3, randomized studyHepatology201664237038026799692

- LawitzEMatusowGDeJesusESimeprevir plus sofosbuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: a phase 3 study (OPTIMIST-2)Hepatology201664236036926704148

- SulkowskiMSGardinerDFRodriguez-TorresMAI444040 Study GroupDaclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infectionN Engl J Med2014370321122124428467

- NelsonDRCooperJNLalezariJPALLY-3 Study TeamAll-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY-3 phase III studyHepatology20156141127113525614962

- FeldJJJacobsonIMHézodeCASTRAL-1 InvestigatorsSofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infectionN Engl J Med2015373272599260726571066

- FosterGRAfdhalNRobertsSKASTRAL-2 Investigators; ASTRAL-3 InvestigatorsSofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infectionN Engl J Med2015373272608261726575258

- SulkowskiMHezodeCGerstoftJEfficacy and safety of 8 weeks versus 12 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) with or without ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 mono-infection and HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection (C-WORTHY): a randomised, open-label phase 2 trialLancet201538599731087109725467560

- ZeuzemSGhalibRReddyKRGrazoprevir-elbasvir combination therapy for treatment-naive cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2015163111325909356

- U.S. Food & Drug AdministrationFDA approves Epclusa for treatment of chronic Hepatitis C virus infection Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm508915.htmAccessed November 12, 2016

- CurryMPO’LearyJGBzowejNASTRAL-4 InvestigatorsSofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosisN Engl J Med2015373272618262826569658

- WylesDBrauNKottililSSofosbuvir/velpatasvir fixed dose combination for 12 weeks in patients coinfected with HCV and HIV-1: the Phase 3 ASTRAL-5 studyJ Hepatol2016642S188S189

- ZeiselMBCrouchetEBaumertTFSchusterCHost-targeting agents to prevent and cure hepatitis C virus infectionViruses20157115659568526540069

- HenkeJIGoergenDZhengJmicroRNA-122 stimulates translation of hepatitis C virus RNAEMBO J200827243300331019020517

- JanssenHLReesinkHWLawitzEJTreatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNAN Engl J Med2013368181685169423534542

- Regulus TherapeuticsRG-101 interim analysis shows 97% response at 8 week follow-up Available from: http://ir.regulusrx.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=955249Accessed November 12, 2016

- PawlotskyJMWhat are the pros and cons of the use of host-targeted agents against hepatitis C?Antiviral Res2014105222524583032

- World Health OrganizationCombating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030 Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hep-elimination-by-2030-brief/en/Accessed October 28, 2016

- Andrieux-MeyerICohnJde AraújoESHamidSSDisparity in market prices for hepatitis C virus direct-acting drugsLancet Glob Health2015311e676e67726475012

- TorjesenIMore UK patients will now be eligible for two costly hepatitis C treatments Available from: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/more-uk-patients-will-now-be-eligible-for-two-costly-hepatitis-c-treatments/20067604.articleAccessed September 14, 2016

- World Health OrganizationGuidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis C infection Updated version, April 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2016/en/Accessed October 22, 2016

- U.S. Food & Drug AdministrationOrange book preface Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/ucm079068.htmAccessed September 14, 2016

- JensenDMSebhatuPReauNSGeneric medications for hepatitis CLiver Int201636792592827306302

- Medicines Patent PoolThe Medicines Patent Pool signs licence with Bristol-Myers Squibb to increase access to hepatitis C medicine daclatasvir Available from: http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/the-medicines-patent-pool-signs-licence-with-bristol-myers-squibb-to-increase-access-to-hepatitis-c-medicine-daclatasvir/Accessed November 12, 2016

- LaneEJJapan’s MHLW sets Sovaldi price, hep C competition heats up Available from: http://www.fiercepharma.com/regulatory/japans-mhlw-sets-sovaldi-price-hep-c-competition-heats-upAccessed September 14, 2016

- WanisHHusseinAEl ShibinyAHCV treatment in Egypt: why cost remains a challenge? Available from: http://www.eipr.org/sites/default/files/pressreleases/pdf/hcv_treatment_in_egypt.pdfAccessed November 14, 2016

- MedhoraSGovernment to subsidise hepatitis C treatment in effort to eradicate disease Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/dec/20/government-pledges-1bn-for-hepatitis-c-treatment-in-effort-to-eradicate-diseaseAccessed September 15, 2016

- ThurszMLacombeKBreaking down barriers to care in hepatitis C virus infectionJ Infect Dis201621371055105626333943

- Bouvier-AliasMPatelKDahariHClinical utility of total HCV core antigen quantification: a new indirect marker of HCV replicationHepatology200236121121812085367

- ChevaliezSSoulierAPoiteauLBouvier-AliasMPawlotskyJMClinical utility of hepatitis C virus core antigen quantification in patients with chronic hepatitis CJ Clin Virol201461114514824973282

- PoiteauLSoulierARosaIPerformance of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in whole blood collected on dried blood spotsJ Viral Hepat201623539940126833561

- SoulierAPoiteauLRosaIDried blood spots: a tool to ensure broad access to hepatitis C screening, diagnosis, and treatment monitoringJ Infect Dis201621371087109526333945

- ChevaliezSPoiteauLRosaIProspective assessment of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus, a tool for improving access to careClin Microbiol Infect2016225459.e1459.e626806260