Abstract

Introduction

There are at least 40 types of Legionella bacteria, half of which are capable of producing disease in humans. The Legionella pneumophila bacterium, the root cause of Legionnaires’ disease, causes 90% of legionellosis cases.

Case presentation

We describe the case of a 60-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension who was admitted to our hospital with fever and symptoms of respiratory infection, diarrhea, and acute renal failure. We used real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect L. pneumophila DNA in peripheral blood and serum samples and urine antigen from a patient with pneumonia. Legionella DNA was detected in all two sample species when first collected.

Conclusion

Since Legionella is a cause of 2% to 15% of all community-acquired pneumonias that require hospitalization, legionellosis should be taken into account in an atypical pulmonary infection and not be forgotten. Moreover, real-time PCR should be considered a useful diagnostic method.

Introduction

Legionella species are Gram-negative bacteria that are ubiquitous in both natural aquatic and moist soil and muddy environments and in artificial aquatic habitats.Citation1,Citation2 Human infection with Legionella spp. has two distinct forms: Legionnaires’ disease, a more severe form of infection which includes pneumonia, and Pontiac Fever, a milder febrile flu-like illness without pneumonia.Citation3 Legionella stands as the cause of community- acquired pneumonia (CAP) in 2%–15% of all CAPs that require hospitalization. The clinical and radiological features of Legionella pneumonia are nonspecific, and the diagnosis depends on laboratory tests.Citation4 This paper reports a case of pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila that was admitted to the general hospital of Komotini in Greece.

Case report

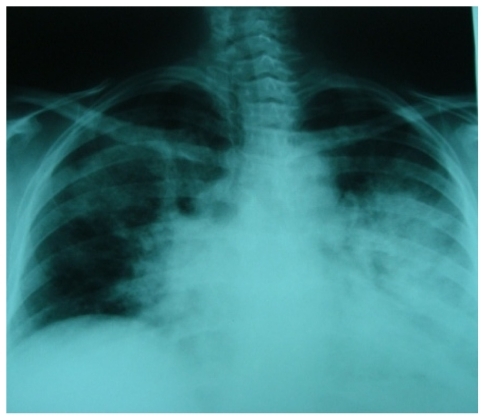

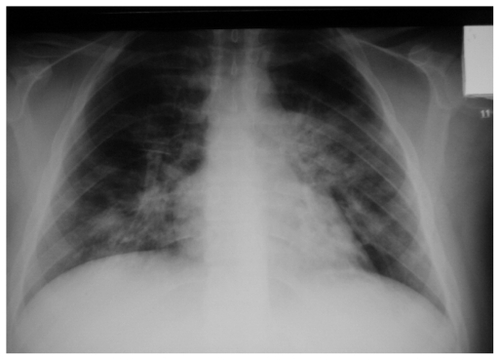

A 60-year-old female with a history of diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and arterial hypertension with a 4-day history of watery diarrhea and temperature was admitted to our hospital. The findings from physical examinations on admission were as follows: temperature 38.6°C, blood pressure 130/95 mm Hg, heart rate 117 beats/min, and respiratory rate 28 breaths/min. Chest auscultation revealed crackles on the left lower lung field. Laboratory findings on admission were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) count was 14,280/μL, creatinine was 3.4 mg/dL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 110/h, procacitonin (PCT) 2 ng/mL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 14 mg/dL (). We considered the elevated creatinine levels as acute, because at her previous laboratory tests her creatinine values never surpassed 1.3 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas showed hypoxemia, as partial pressure of oxygen on air was 56 mm Hg.Citation5 The chest X-ray showed infiltration of the left lung (). With a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, urine samples for L. pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen, gram stain sputum, and blood specimens upon admission were collected from the patient for culture testing.Citation6 The results were reported negative. The pneumonia severity index (PSI) was evaluated as class 3 with a mortality rate of 0.9%.Citation7 The patient was treated empirically with 1 g amoxycillin/clavulanic acid three times daily and 500 mg clarithromycin two times daily for 2 days. Empiric antibiotic treatment was added upon admission based on elevated values of CRP, WBC, ESR, and chest X-ray findings, since early antibiotic treatment prevents progression of the disease and these markers are known to be elevated in infectious diseases.Citation8,Citation9 The clinical status of the patient was deteriorating, and there was a marked progression of the infiltrates on the chest X-ray; the left infiltrate progressed to bilateral shadows. The laboratory values were as follows on the 2nd hospital day: WBC count 17,780/μL, CRP 18 mg/dL, PCT 2 ng/mL, and ESR 120/h. The patient’s hypoxemia increased: partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) 47 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) 25.4 mm Hg, and pH 7.5 (). The patient’s respiratory rate increased 30/h. One day after her admission to hospital (day 2) (), two blood samples, one serum sample and a second urine sample were taken and tested for L. pneumophila with a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Aqua Screen L. pneumophila-detection kit for real-time PCR; Minerva Biolabs, Minerva, OH) and with culture method. The test revealed positive for L. pneumophila. A portion of 200 μL of blood and an equal volume of serum were plated on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) (Oxoid, Reading, UK) with L-cysteine, on BCYE without L-cysteine, and on GVPC (gas vesicle protein C). No growth of Legionella spp. was noticed after several days of incubation. The Legionella urinary antigen detection test was positive.

Table 1 Laboratory findings

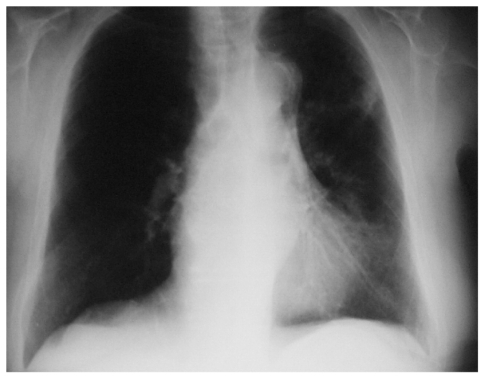

The antibiotics were immediately changed to levofloxacin after the positive real-time PCR and Legionella urinary antigen detection test. The patient responded after therapy with levofloxacin, on day four (). Her general condition, as well as radiographic and laboratory findings, gradually improved and the patient was discharged on the 21st day of hospitalization ().

To identify the source of the infection, the patient’s relatives were interviewed. Exposure histories revealed that the patient had travelled abroad and visited an operating spa pool 2 weeks before the day of onset. After she returned, she remained in her village until her admission to hospital. As there were no cooling towers or any aerosol-generating systems in an area of 2 km from the house, and there was no access to the spa pool abroad, environmental samples were taken only from the home water supplies, and standard methods were processed. Water samples revealed an absence of Legionella spp. from the domestic water supplies.

Discussion

The incidence of Legionnaires’ disease has increased in the last decade since the introduction of urinary antigen immunoassays.Citation10,Citation11 This test accounts for most of the diagnostics due to its high sensitivity and ease of use.Citation12 L. pneumophila has become one of the leading causes of CAP in adults, accounting for 6%–14% of cases requiring hospitalization in recent studies.Citation13,Citation14

Legionnaires’ disease occurs sporadically and in outbreaks, with the sporadic form representing 65%–82% of the cases.Citation10,Citation11,Citation15 Nevertheless, the number of confirmed community outbreaks including more than 100 cases has increased in recent years due to the use of Legionella antigenuria.Citation11,Citation15 Routine testing for Legionella urinary antigen has increased the number of diagnostics of Legionnaires’ disease and has allowed earlier diagnosis and treatment, greatly improving the prognosis.Citation16 This has been particularly true for milder cases, mainly in the outbreak setting.Citation17 However, most of the knowledge on risk factors, clinical presentation, and outcome of community-acquired Legionnaires’ disease is based on studies performed before routine urinary antigen testing was adopted.Citation18,Citation19 Moreover, recent community outbreaks have contributed to the better understanding of Legionnaires’ disease in this setting.Citation20–Citation22

Legionella pneumophila has been recognized as an important cause of both CAP and nosocomial pneumonia.Citation1,Citation10,Citation11,Citation23 Environmental systems, such as air conditioning cooling towers, evaporative condensers, whirlpools, and hot spring baths have hosted and transmitted the organism. Cases of Legionella pneumonia presumably transmitted from contaminated hot spring spa water have been reported from Greece.Citation23 The early recognition of infection due to Legionella plays a major role in its treatment and preventing mortality in patients with any underlying disease.Citation24,Citation25 In this case, the PCR method was lifesaving for the patient because it confirmed the infection, leading to the administration of the right treatment, whereas the first urine antigen test was misleading. This way of diagnosing Legionella has been well established in previous published studies, and it should be applied in such cases where a differential diagnostic problem exists.Citation26,Citation27

Legionnaires’ disease is an acute bacterial infection generally caused by L. pneumophila, primarily involving the lower respiratory tract. Outbreaks have been described related to a common source of contamination.Citation1 Erythromycin has been the treatment of choice ever since a retrospective study of the original outbreak in Philadelphia indicated a lower mortality rate with this antibiotic. Because Legionella is an intracellular pathogen, antibiotics that penetrate intracellularly are likely to be active against this pathogen. Both fluoroquinolones and macrolides penetrate cells well, and both classes demonstrate good in vitro activity. Fluoroquimolones achieve high intracellular levels and have a lower minimum inhibitory concentration against Legionella than erythromycin.Citation28 They are more active than erythromycin in inhibiting L. pneumophila in different intracellular models. Three observational studies with a total of 458 patients have indicated that fluoroquinolones (mainly levofloxacin) are associated with a superior clinical response when compared with that of macrolides (erythromycin and clarithromycin), as evidenced by a shorter time to apyrexia, shorter hospital stay, and fewer drug-related complications.Citation29–Citation31

However, no randomized trials have been performed yet. Mortality appears to be the same. Although it has been traditional to add rifampin to erythromycin to treat severe legionellosis, an observational cohort study revealed that the addition of rifampin to clarithromycin was associated with more side effects and a longer hospitalization stay than erythromycin alone.Citation30,Citation32 In all cases of severe, life-threatening pneumonia, prompt administration of appropriate antibiotics is associated with improved outcomes.

This case should urge every clinical doctor to study carefully the medical history of a patient and consider alternative diagnosis when the patient is not responding to the initial treatment. Flouoroquinolones have established an equal if not superior therapeutic profile for legionellosis based upon published studies.Citation28–Citation30 It should be mentioned at this point that a very important limitation of the study was that we were unable to take water samples from the spa in order to have a solid confirmation of the source of legionellosis.

Conclusion

PCR is a useful tool in the hands of the clinical doctor and should be used where possible in suspicious cases, such as the above. Also, early antibiotic treatment prevents the progression of the infection and should be administered upon admission. Finally, flouoroquinolones, and in this case levofloxacin, should be considered an effective and efficacious treatment for legionellosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next-of-kin for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

PZ was responsible for the medical care of the patient and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. GR and IA were responsible for the PCR examination. KZ, TK, and ET were also responsible for the medical care. AS analyzed the radiologic examination, and TCC is the department chair. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- FieldsBSBensonRFBesserRELegionella and Legionnaires’ disease: 25 years of investigationClin Microbiol Rev20021550652612097254

- Garcia-VidalCCarralaJFernandes-SabeNAetiology of and risk factors for recurrent community-acquired pneumoniaClin Microbiol Infect200915111033103819673961

- KohnoSPontiac fever: non-pneumonic form of legionellosisIntern Med1998712100310049932628

- BramMWDKluytmansJAJWvan den Broucke-GraulsCMPetersMFUtility of real-time PCR for diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease in routine clinical practiceJ Clin Microbiol20084667167718094136

- LeeWLSlutskyASMasonMurrayNadelTextbook of Respiratory Medicine4th edPhiladelphia, PASaunders, Elsevier2005

- AnevlavisSPetroglouNTzavarasAA prospective study of the diagnostic utility of sputum Gram stain in pneumoniaJ Infect2009592838919564045

- FineMJAubleTEYealyDMA prediction rule to identify low- risk patients with community-acquired pneumoniaN Engl J Med19973362432508995086

- Ortega-DeballonPRadaisFFacyOC-Reactive protein is an early predictor of septic complications after elective colorectal surgeryWorld J Surg201034480881420049435

- GeorgeELPanosADoes a high WBC count signal infection?Nursing2005351202115622174

- JosephCAfor the European Working Group for Legionella InfectionsLegionnaires’ disease in Europe 2000–2002Epidemiol Infect200413241742415188711

- AlvarezJOyagaNEscofetACodonyFOrcauAMaria OlivaJCommunity-acquired legionellosis in the Barcelona region between 1992 and 1999: epidemiological characteristics and diagnostic methodsMed Clin (Barc)200111749549611707205

- Den BoerJWYzermanEPDiagnosis of Legionella infection in Legionnaires’ diseaseEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis20042387187815599647

- GuptaSKSarosiGAThe role of atypical pathogens in communityacquired pneumoniaMed Clin North Am2001851349136511680106

- SopenaNSabriaMPedro-BotetMLProspective study of community- acquired pneumonia of bacterial etiology in adultsEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis19991885285810691195

- AlvarezJDominguezASabriaMthe Working group of communicable diseases of the RCESPCommunity outbreaks of legionellosis in Catalonia, 1990–2003 [abstract 1324]Abstracts of the 15th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious DiseasesCopenhaguen, DenmarkEuropean Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases200511Suppl 2424s

- BeninALBensonRFBesserRETrends in Legionnaires’ disease, 1980–1998: declining mortality and new patterns of diagnosisClin Infect Dis2002351039104612384836

- FormicaNYatesMBeersMThe impact of diagnosis by Legionella urinary antigen test on the epidemiology and outcomes of Legionnaires’ diseaseEpidemiol Infect200112727528011693505

- MarstonBJLipmanHBBreimanRFSurveillance for Legionnaires’ disease. Risk factors for morbidity and mortalityArch Intern Med1994154241724227979837

- StrausWLPlouffeJFFileTMJrRisk factors for domestic acquisition of legionnaires’ disease. Ohio Legionnaires’ Disease GroupArch Intern Med1996156168516928694667

- Garcia-FulgueirasANavarroCFenollDLegionnaires’ disease outbreak in Murcia, SpainEmerg Infect Dis2003991592112967487

- GreigJECarnieJATallisGFAn outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease at the Melbourne Aquarium, April 2000: investigation and case-control studiesMed J Aust200418056657215174987

- Den BoerJWYzermanEPSchellekensJA large outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease at a flower show, the Netherlands, 1999Emerg Infect Dis20028374311749746

- MavridouASmetiEMandilaraGPrevalence study of Legionella spp. contamination in Greek hospitalsInt J Environ Health Res200818429530418668417

- SopenaNForceLPedro-BotetMLSporadic and epidemic community legionellosis: two faces of the same illnessEur Respir J20072913814217005576

- Pedro-BotetMLSabria LealMHaroMNosocomial and community- aquired Legionella pneumonia:clinical comparative analysisEur Respir J19958192919338620964

- WeltiMJatonKAltweggMSahliRWengerABilleJDevelopment of a multiplex real-time quantitative PCR assay to detect Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in respiratory tract secretionsDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis2003452859512614979

- GinevraCBarrangerCRosADevelopment and evaluation of Chlamylege, a new commercial test allowing simultaneous detection and identification of Legionella, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in clinical respiratory specimens by multiplex PCRJ Clin Microbiol20054373247325416000443

- Pedro-BotetLYuVLLegionella: macrolides or quinolones?Clin Microbiol Infect200612Suppl 3253016669926

- SabriaMPedro-BotetMLGomezJLegionnaires Disease Therapy GroupFluoroquimolones vs macrolides in the treatment of Legionnaires’ diseaseChest20051281401140516162735

- MykietiukACarratalaJFernandez-SabeNClinical outcomes for hospitilized patients with Legionella pneumonia in the antigenuria era: the influence of levofloxacin therapyClin Infect Dis20054079479915736010

- YuVLGreenbergRNZadeikisNLevofloxacin efficacy in the treatment of community-aquired legionellosisChest20041252135213915189933

- GrauSMateu-de AntonioJRibesESalvadoMGarcesJMGarauJImpact of rifampincin to clarithromycin in Legionella pneumophila pneumoniaIntern J Antimicrob Agents200628249252