Abstract

Pneumococcal disease is a global public health concern that significantly contributes to clinical disease burden and economic burden. Patients frequently afflicted are young children and older adults, as well as the immunocompromised population. Immunization is the most effective public health strategy to combat pneumococcal disease and several vaccine formulations have been developed in this regard. Although vaccines have had a significant global impact in reducing pneumococcal disease, there are several barriers to its success in Iraq. The war and conflict situation, increasing economic crises and poverty, poor vaccine accessibility in the public sector, and high vaccine costs are a few of the major obstacles that impede a successful immunization program. The last reported third dose pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage for Iraq was 37% in 2019, which is expected to reduce even further owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, strategies and policies to improve pneumococcal vaccine availability and coverage need to be strengthened to achieve maximum benefits of immunization. In the current review, we provide an overview of the existing knowledge on pneumococcal disease-prevention strategies across the globe. The main aim of this manuscript is to discuss the current status and challenges of pneumococcal vaccination in Iraq as well as the strategies to prevent pneumococcal infections.

Introduction

Pneumococcal disease refers to any infection caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is a major public health concern due to its high rate of global morbidity and mortality. The incidence rate of pneumococcal disease is more in children <2 years and adults ≥65 years.Citation1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about a million children succumb to this disease annually, with more than 300,000 being under 5 years of age.Citation2,Citation3 In the Eastern Mediterranean region, the incidence of pneumococcal disease in 2015 was estimated to be 1261/100,000 children (<5 years), of which 1214/100,000 were caused by pneumococcal pneumonia.Citation4 In this region, the overall mortality due to pneumococcal disease among children (<5 years) was reported to be around 47/100,000, with a major burden (39/100,000) due to pneumococcal pneumonia.Citation4 As per the data for 2015, Iraq had an estimated pneumococcal disease burden of 111,636 incidents and 1954 deaths, with 79,601 incidents and 1669 deaths caused by pneumococcal pneumonia.Citation4,Citation5 These figures are among the highest in the region for upper middle income countries (UMICs).

Pneumococci are Gram-positive bacteria that are encapsulated within a polysaccharide capsule, which is an important virulence factor.Citation6 They are disseminated via direct contact with respiratory secretions (mucus or saliva) from patients as well as healthy carriers. The pathogen may affect various organ systems, thereby manifesting in the form of varied, invasive or noninvasive, pneumococcal infections. Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) implies an infection that can be confirmed by the isolation of the pathogenic pneumococcal species from a sterile body site, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and synovial, peritoneal, or pleural fluid.Citation7 Severe, life-threatening IPD conditions include meningitis, bacteremic pneumonia, and febrile bacteremia, while sinusitis, otitis media, bronchitis, and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are the milder, but more common, noninvasive manifestations.Citation8 IPD has a high mortality rate among children (<5 years) in developing countries, ranging from up to 20% for sepsis to up to 50% for meningitis.Citation9 Pneumococcal pneumonia is a global killer and may be acquired in different settings, such as within the community (CAP) or in the form of a nosocomial infection (hospital-acquired pneumonia: HAP).Citation10

More than 90 different capsular serotypes of the pathogen have been identified worldwide. These serotypes have been defined based on differences in their capsular polysaccharide composition.Citation11 The distribution of these serotypes has been seen to vary with time. Several factors, such as geographical region, presence of antimicrobial resistance genes, disease syndrome and severity, as well as the age of the population, determine the serotype distribution.Citation9 A study reported that prior to the global introduction of conjugate vaccines (period of study: 1980–2007), ≥70% of all childhood (<5 years) IPD cases were caused by only 6–11 pneumococcal serotypes.Citation12 Serotypes 1,5, 6A, 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F prevailed among children (<5 years) in the pre-PCV period while serotypes 19A, 3, and 6A were common following the introduction of PCV7 and PCV10/13.Citation12,Citation13 A systematic review and meta-analysis of publications between 2000 and 2015 showed that 22F, 12F, 33F, 24F, 15C, 15B, 23B, 10A, and 38 were the predominant non-PCV13 serotypes globally.Citation13 The limited serotype surveillance data in Iraq limits our ability to effectively report the common serotypes circulating in Iraq.

Apart from age, several health conditions, such as diabetes, nephrotic syndrome, CSF leak, and cochlear implants can increase the risk of developing severe, invasive infections. An immunocompromised status resulting from disease (HIV, sickle cell disease, asplenia, cancer) or drug use (steroids), as well as substance abuse (alcoholism, cigarette smoking), is a risk factor for developing pneumococcal disease.Citation14 Additionally, S. pneumoniae infections may exacerbate chronic lung illnesses such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and emphysema—thereby adversely affecting patient outcomes.Citation15

Vaccination is the primary preventive strategy against pneumococcal disease. lists the different pneumococcal vaccine preparations that have been developed to combat pneumococcal disease. In fact, the introduction of vaccination has significantly reduced the pneumococcal disease burden across the globe.Citation4 In addition, it has also helped in controlling the incidence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections.Citation16 However, the coverage of the pneumococcal vaccines has been reported to be very low (~37%), even for a UMIC such as Iraq.

Table 1 Pneumococcal Vaccines

The purpose of this (narrative) review is to consolidate existing knowledge on global pneumococcal disease-prevention strategies. Further, it aims to identify and understand the barriers affecting pneumococcal immunization in Iraq and propose possible strategies that may be adopted to prevent such infections in the susceptible adult and pediatric Iraqi populations.

Pneumococcal Infection Landscape: Epidemiology and Transmission

S. pneumoniae is a part of the commensal microflora of the upper respiratory tract and colonizes the nasopharynx.Citation25 Infants and young children are the major carriers of this bacteria, with a carriage rate of 27–85%, while in adults, the rate is <10%.Citation26,Citation27 It has been observed that children in low- and middle-income countries, as well as a few indigenous populations within high-income countries, have a higher carriage rate.Citation27–30 Pneumococcal carriage contributes to the horizontal spread of the pathogen within communities and is thus a prerequisite for disease. Carriage also helps build immunity against the pathogen and is normally asymptomatic. However, the migration of this opportunistic pathogen into sterile tissues and organs of the human body may give rise to severe disease.Citation31

The Pneumococcal Global Serotype Project established that in children <5 years only a few serotypes (6–11) were responsible for a majority (≥70%) of IPD cases, both globally and regionally.Citation12 The most common global IPD serotypes were 1, 5, 6A, 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F, which accounted for 200,000 and >300,000 deaths in Asia and Africa, respectively, in the year 2000.Citation12

Epidemiological reports on pneumococcal disease prevalence in Iraq have been relatively lacking, although a recent study conducted between June 2018 and May 2020 across 18 major hospitals in Iraq showed that 41.6% of confirmed bacterial meningitis cases were caused by S. pneumoniae.Citation32 Although the age of the patients ranged between 1 week to 40 years, a majority (83.7%) of these patients were <5 years, with 58.4% being under 1 year of age. The overall annual incidence rate of pneumococcal meningitis in the country was 0.62/100,000 population, with the maximum reported in Karbala (1.56), followed by Karkh (0.65), Al-Rusafa (0.58), Kirkuk (0.3), and Maysan (0.09).Citation32 The annual Arba’een pilgrimage may be a major determining factor for the high pneumococcal meningitis incidence in Karbala city. Such dense mass gatherings create a conducive environment for the dissemination of infectious diseases.Citation33

Global Burden of Pneumococcal Disease

Clinical Burden of Pneumococcal Disease

According to the WHO, in 2019, infections of the lower respiratory tract (LRT) were the 4th leading global cause of mortality (low-income countries [LICs]: 2nd leading cause, middle-income countries [MICs]: 5th leading cause, high-income countries [HICs]: 6th leading cause).Citation34 In fact, they are the world’s deadliest communicable diseases, having claimed 2.6 million lives in 2019.Citation34 Infectious diseases, in general, are the chief cause of mortality among children (<5 years).Citation35 Globally, pneumonia is the single largest infectious cause of mortality among children.Citation36 S. pneumoniae is the most prevalent bacterial cause of childhood pneumonia. In 2016, pneumococcal pneumonia was responsible for 1,189,937 deaths and 197.05 million incidents.Citation37 Of these, 341,029 deaths occurred in children (<5 years) and 494,340 deaths occurred in the elderly population (>70 years). The burden of disease (number of cases and mortality rate) was observed to be higher in developing nations, with the majority of deaths being observed in Africa and Asia. shows the burden (mortality and morbidity) of pneumococcal disease for the year 2015 in different countries (selected randomly), based on their WHO region and World Bank income group. Iraq has one of the highest disease burdens among the UMICs in the Eastern Mediterranean region ().

Table 2 Overview of Pneumococcal Vaccine Introduction, Vaccine Coverage and Disease Burden in Different Countries of the World

The socioeconomic status of countries also determines the incidence and outcomes of pneumococcal disease, with a higher occurrence rate being associated with nutritional deficiencies among children, poor hygiene, and increased indoor air pollution.Citation38 Among children (<2 years) in Europe, the mean annual incidence of IPD was reported to be 44.4/100,000, prior to the introduction of conjugate vaccines.Citation39 On the other hand, rural Mozambique had an annual incidence rate of 779/100,000 (<3 months of age).Citation40 In India, pneumococcal pneumonia claimed the lives of about 105,000 children (<5 years) in 2010 with 564,000 episodes of severe disease.Citation41 It was estimated that 294,000 HIV-uninfected children (<5 years) and 23,300 HIV-infected children died from pneumococcal disease in 2015 worldwide.Citation4 Pneumococcal meningitis and bacteremia claimed the lives of approximately 3250 people in the USA in 2019.Citation42 The global annual mortality due to CAP is estimated to be around 3 million.Citation43

Economic Burden of Pneumococcal Disease

Pneumococcal disease imposes a significant burden on the economy owing to its high clinical burden. An estimated 150,000 hospitalizations take place in the USA per year as a result of pneumococcal pneumonia.Citation42 In 2004, direct health care costs due to pneumococcal disease were US $3.5 billion in the USA, with a majority (US $1.8 billion) due to adult patients ≥65 years.Citation44 It is estimated that between 2004 and 2040, the economic burden of pneumococcal pneumonia will increase by US $2.5 billion per year.Citation45 About 1.3 million episodes of CAP occur in the USA every year within the ≥65 years age bracket, with almost 40% having a hospital stay of 5.6 days on average. The financial burden for each episode can reach an excess of US $18,000, causing Medicare an estimated burden of US $13 billion annually.Citation46 Total health care costs associated with CAP among adults (≥50 years) in Europe were estimated to be as high as US $11.18 billion per year.Citation47 One-third of the costs were related to indirect costs, ie, loss of working days. An IQVIA real-world study performed on adult (≥18 years) patients in Dubai (using claims data from 2014 to 2019) found that the treatment of pneumonia was associated with an average cost of US $1305 per patient with a higher health care burden (US $10,207) noted in the high-risk cohorts. This is approximately 8–11 times the average cost in the medium-risk (US $1283) and low-risk (US $882) cohorts.Citation48

Global Prevention Strategies

Vaccines

Vaccination is the primary preventive strategy against pneumococcal disease. Two kinds of vaccines have been developed in this regard: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPSVs) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) (). The generation of antibodies against capsular polysaccharide antigens provides serotype-specific protection against pneumococcal disease. Cross-protection among related serotypes (6A/6B, 6A/6C, and 19A/19F) has also been observed.Citation9 The vaccines have been designed to cover serotypes associated with severe forms of the disease.

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccines

In 1977, the first PPSV was approved for use in the USA; it was a formulation of purified capsular polysaccharide antigens from 14 different S. pneumoniae serotypes ().Citation49 It was replaced by the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Pneumovax® 23) in 1983 (). The 23 serotypes present in this formulation cause 90% of the invasive infections in developed nations.Citation2 The vaccine is priced between US $5 and $35 per dose.Citation50

Polysaccharide antigens are thymus independent and therefore have poor immunogenicity and do not induce immunological memory.Citation51 They lead to a B-cell-dependent immune response via the production of IgM antibodies.Citation52 As children below 2 years of age have an underdeveloped immune system, polysaccharide vaccines are not recommended for them.

Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines

Conjugation of the capsular polysaccharides to a carrier protein enhances their immunogenicity, making them more effective against infection, particularly in children <2 years. The first pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7, Prevnar®) included capsular polysaccharides of 7 serotypes individually conjugated to the diphtheria CRM197 carrier protein (cross-reacting material 197, a nontoxic variant of diphtheria toxin) (). These 7 serotypes included 65–80% of the serotypes associated with IPD among children in developed western countries.Citation19 The vaccine directly protects immunized children and indirectly protects the community via reduced nasopharyngeal colonization and transmission, ie, herd immunity.Citation53 Furthermore, the conjugation of the capsular polysaccharides to the CRM197 protein results in a thymus-dependent adaptive immune response, which is associated with isotype switching and the generation of memory B-cells.Citation52

PCV7 production was phased out in favor of the 10-valent PCV (Synflorix®, PCV10), which is made up of 3 additional capsular polysaccharides from serotypes 1, 5, and 7F ().Citation54 In this formulation, protein D of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) acts as the carrier protein for 8 serotypes, while 2 serotypes (18C and 19F) are conjugated to the tetanus and diphtheria toxoids, respectively.Citation20 In 2010, the 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar® 13) was licensed for protection against 3 additional serotypes (3, 6A, and 19A) ().Citation22 It was reported that in the year 2000, serotypes included in both the 10- and 13-valent PCVs accounted for 10 million cases and 600,000 deaths worldwide.Citation12

Recently, in 2021, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a 15-valent PCV (PCV15, Vaxneuvance®, MSD), containing 2 additional pneumococcal polysaccharides from serotypes 22F and 33F ().Citation23 In 2021, a 20-valent PCV (PCV20, Prevnar 20®, Pfizer) with 5 additional serotypes (8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B) was also introduced to the US market ().Citation24 Additionally, a novel 24-valent PCV vaccine candidate (Affinivax) is currently under clinical trial.Citation55

Pneumosil®, another 10-valent product developed by a collaboration between the Serum Institute of India, PATH, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, was released in 2020 (). Apart from its affordability, the formulation offers the presence of serotypes 6A and 19A, which are more prevalent in high-disease-burden regions such as Asia and Africa.Citation56

Introduction Status, Pneumococcal Vaccination Program, and Vaccine Formulations

The WHO recommends the inclusion of PCVs in childhood immunization programs globally.Citation9 A WHO report states that 91% of the global pneumococcal vaccine market demand is PCV-driven, with more than 95% coming from childhood immunization programs.Citation50 However, prior to introducing a vaccine into the National Immunization Program (NIP), each country needs to focus on 3 main areas of concern pertaining to the disease, the vaccine, and the strength of the immunization program and health care system.Citation57

The disease targeted by the vaccine should be a public health and political priority.Citation57 A few questions need to be asked in this regard that are beneficial in the decision-making process:Citation57

Does the disease in question have a significant burden?

Does its prevention contribute significantly to the goals, and is it consistent with the priorities of national health and development programs?

Is the disease of significance to the public and medical community?

Has the vaccine been recommended by WHO, and is control of the disease in accordance with global or regional priorities?

Does disease prevention aid in equity improvement among the socioeconomic classes and population groups?

The performance of the available vaccine, with respect to its efficacy, safety, and effectiveness, should also be taken into consideration prior to its introduction into the NIP.Citation57 Additionally, the characteristics of the vaccine product (number of doses required, formulation, presentation, and packaging), as well as the availability of vaccine supply, should be assessed. Several economic and financial issues related to vaccine introduction are critical and should be analyzed properly, such as the vaccine’s cost-effectiveness, affordability, and financial sustainability.Citation57 Finally, the impact of vaccine introduction on the immunization program as well as the existing health care system of the country needs to be evaluated, including its ability to deliver without a burden on other (critical) health services.Citation57

Based on the above factors, a decision may be taken by policymakers to introduce the vaccine in the NIP, thereby providing market access across all applicable age groups (eg, USA and Canada). Alternately, the vaccine may be included in the NIP but may provide market access to limited age groups (eg, Kazakhstan—adult only, India—pediatric and under 5) or have a varying dosage schedule (eg, Canada). Based on market health, the vaccine may also be adopted subnationally (in a regional or phased manner), resulting in limited market access (eg, Spain—regional and Philippines—phased).Citation5

Globally, PCV has been introduced in 148 countries, while 18 countries are planning to do so and 28 countries are yet to decide.Citation5 The vaccine has been introduced under 3 program types: universal introduction in 142 countries, subnational introduction in 2 countries, and introduction among high-risk populations in 4 countries.Citation5

The USA and Canada, within the region of the Americas, were the first to adopt PCV use in 2000 and 2002, respectively (). A few countries in Europe (Italy) and the Western Pacific region (Australia) incorporated the vaccine into the NIP in 2005 (). The Eastern Mediterranean region also started the introduction of PCV in childhood immunization programs around the same time in countries such as Qatar (2005), Kuwait (2007), and Bahrain (2008), while African countries such as Gambia, South Africa, and Rwanda followed in 2009 (). The Southeast Asian region was the last to incorporate PCV in the NIP, with Nepal and Bangladesh in 2015 (). presents the status of PCV introduction in a few countries in different WHO regions, their income status (as per the World Bank), and provides information related to the PCV introduction program type, vaccine coverage status, dosing schedule, and disease burden in these countries. A quick glance at tells us that PCV introduction began first in many HICs.

Three kinds of PCV formulations (Prevnar 13®/PCV13, Synflorix®/PCV10, Pneumosil®/PCV10) are currently in use, with PCV13 being the most widely used among both pediatric and adult populations.Citation5 India is the only country that has introduced the 10-valent Pneumosil®.Citation5 The choice of a particular vaccine formulation should be governed by programmatic factors, vaccine price and supply, serotype prevalence, and pattern(s) of antibiotic resistance in the country.Citation9 Affordability is a major factor that drives PCV introduction in MICs. It has been reported that while 92% of HICs and 82% of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI)-supported countries currently have PCV programs, this percentage is only 66% for MICs.Citation55 The per dose range for PCV is between US $3 for GAVI countries and US $132 in the USA.Citation50 For self-procuring countries, prices vary based on income status, with US $16 for lower middle-income countries (LMICs), US $19 for UMICs, and US $37 for HICs. Pneumosil® is the cheapest product at US $2 per dose GAVI price.Citation56

Dosing Schedule and Target Population

Currently, 3 PCV products have been prequalified by the WHO for administration to infants and children, viz. Prevnar 13®, Synflorix®, and Pneumosil®.Citation9 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all children <2 years of age receive the PCV13 vaccination. Additionally, children (2–18 years) with risk factors or those having certain medical conditions are recommended to get PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccinations.Citation42 The WHO recommends a 3-dose schedule (2p+1: 2 primary doses and a booster dose or 3p+0: 3 primary doses and no booster dose) for administration of PCV in infants and children (<5 years).Citation9 The former schedule has been found to be more beneficial than the 3p+0 schedule, as it induces higher antibody titers by 2 years of age.Citation9

In adults, the vaccines currently available globally for preventing pneumococcal disease are PPSV23 and PCV13.Citation58 The USA has 2 additional conjugate vaccines (PCV15 and PCV20) for use in adults. For vaccination in adults (≥65 years or 19–64 years with certain medical conditions or risk factors), the CDC recommends one dose of PCV15 or PCV20. PCV15 use should be followed by vaccination with PPSV23.Citation42

Four approved PCV dosing regimens are being used worldwide among children (1p+1: 1 primary dose and a booster dose, 2p+1, 3p+0 and 3p+1: 3 primary doses and a booster dose).Citation5 PCV vaccines are administered to only adult, only pediatric or both adult and pediatric populations in different countries across the world (adult: 2 countries, pediatric: 30 countries, adult and pediatric: 54 countries).Citation5 The 3p+0 dosing schedule has been adopted in 61 countries, while the 2p+1 schedule is being followed in 60 countries.Citation5 The UK is the only country to use a 1p+1 maintenance program, which involves administering a primary dose of PCV13 at 3 months and a booster dose at 12–13 months.Citation59

Saudi Arabia hosts the largest annual mass gathering, the Hajj pilgrimage, which increases the risk of dissemination of pneumococci among the global population. There are several reports that show increased pneumococcal carriage among pilgrims post-Hajj.Citation60,Citation61 The Scientific Committee for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination of the Saudi Thoracic Society recommends the following guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination before Hajj season: a) combined PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccination in people ≥50 years prior to Hajj; however, only a single dose of PPSV23 is recommended in people planning to take it immediately before Hajj; (b) single dose of PPSV23 at least 3 weeks before Hajj in immunocompetent adults <50 years of age with risk factors.Citation62

Coverage Status

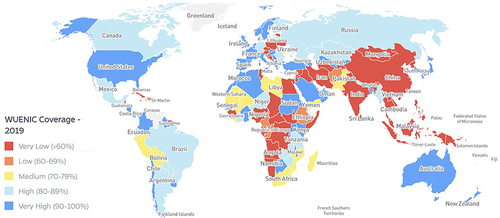

In 2020, the coverage for 3 doses of PCV vaccination among children was 49% globally.Citation63 The WHO region-wise coverage for 2020 was 16% for the Western Pacific region, 27% for the Southeast Asian region, 52% for the Eastern Mediterranean region, 68% for the African region, 76% for the region of the Americas, and 79% for the European region ().Citation63 In the USA in 2018, pneumococcal vaccine coverage (≥1 dose) (PPSV23 or PCV13) among high-risk individuals (19–64 years) was 23.3% and among adults ≥65 years was 69%.Citation64 Between 2010 and 2018, this coverage ranged from 18.5% to 24.5% in the former cohort and from 59.7% to 69.0% in the latter. In the UK, the coverage of PPSV23 among adults ≥65 years was 70.6% till March 2021, and for high-risk individuals aged 2–64 years, it was 38.5% (chronic liver disease) and 70.7% (cochlear implants).Citation65

Figure 1 World map highlighting the WUENIC coverage for PCV for the year 2019.

Global Impact of Pneumococcal Vaccines: Case Studies

Due to the expanded coverage of PCVs, the mortality due to LRT infections occurring as a result of pneumococcal pneumonia has reduced globally by 7.24%.Citation37 PCV13-based immunization programs have had a global impact on public health, having averted 175.2 million episodes of (all) pneumococcal disease and 624,904 deaths between 2010 and 2019.Citation66 It has been reported that pneumococcal disease-related mortality declined by 51% between 2000 and 2015.Citation4

In 2018, an economic-epidemiological analysis was performed to determine the potential impact of introducing PCV13 into the Indian NIP.Citation67 The authors estimated that if a vaccine coverage (~77%) and distribution level similar to the DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) vaccine were adopted, PCV13 vaccination would cost ~US $240 million, but also help save US $48.7 million in out-of-pocket expenditure and prevent 34,800 deaths annually.

PCV13 has been in use in Africa and the Middle East since 2010. The public health benefit of its use in children <5 years was evaluated across 46 countries by an epidemiological model, which established that approximately 123.5 million infants were vaccinated with PCV13, resulting in an estimated 115 million cases of disease and 517,274 associated deaths averted.Citation68

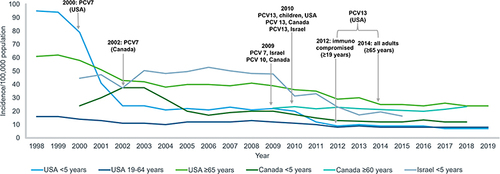

Between 1999 to 2015, a total of 4457 IPD cases were identified in children <5 years in Israel, with 76.2% being severe and 22.9% being nonsevere. Following PCV7 and PCV13 introduction into the NIP of Israel, there was a >60% decrease in overall IPD cases in children <5 years ().Citation69

Figure 2 Trends in IPD incidence among children and adults before and following introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in different countries.

USA: The Case of Herd Immunity and a Major Decline in Pneumococcal Disease Incidence

In the USA, PCV 7 was licensed and incorporated into the childhood immunization program in 2000, after which the incidence of PCV7-serotype-related IPD cases dropped by 99%.Citation70 Herd immunity was also observed among the unvaccinated population. A minor increase in non-PCV7-serotype-related IPD incidence was observed between 2000 and 2010.Citation70 However, these were controlled by the replacement of PCV7 with PCV13 in 2010. Between 1998 and 2019, there was a 93% decrease in overall IPD cases among children <5 years ().Citation71 Within the same time period, the incidence of IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes declined from 88 cases/100,000 individuals to 2 cases/100,000 individuals (98% decrease).Citation71 Experts believe that PCV13 has helped to prevent 30,000 IPD episodes and 3000 deaths within the first 3 years of its introduction.Citation70 A decade after the introduction of PCV7 into the US childhood immunization schedule, there were an estimated 168,000 fewer hospitalizations due to pneumonia annually.Citation72

In 2012, PCV13 was incorporated for adults (≥19 years) with an immunocompromised status and in 2014 for all adults ≥65 years. However because of herd protection, a decline in overall IPD incidence among adults (≥19 years) was seen as early as 2001 ().Citation71 Between 1998 and 2019, the overall incidence of IPD in the 19–64 years and ≥65 years age brackets reduced from 16/100,000 individuals to 8/100,000 individuals and from 61/100,000 individuals to 24/100,000 individuals, respectively (). Specifically, IPD due to PCV13 serotypes dropped by 82% (11/100,000 individuals to 2/100,000 individuals) and 87% (45/100,000 individuals to 6/100,000 individuals) among people aged 19–64 years and ≥65 years, respectively.Citation71

Canada: The Case of Dual Vaccine Dosage Schedules

PCV7 was introduced across all Canadian provinces and territories between 2002 and 2006, which resulted in a dramatic reduction in pneumococcal disease incidence, as well as in vaccine serotype strains among children <5 years ().Citation73 Following its introduction, the incidence of pediatric IPD cases due to non-PCV7 serotype strains (viz. 7F and 19A) increased.Citation74,Citation75 However, these were controlled by the introduction of the 10-valent and 13-valent PCVs in 2009 and 2010–2011, respectively. The country has a dual dosage schedule of 2p+1 and 3p+1. In the 2p+1 program, 2 primary PCV doses are administered at 2 and 4 months, and a booster at 1 year. However, in high-risk and immunocompromised children, the 3p+1 schedule is used, where 3 primary doses are given at 2, 4, and 6 months and a booster at 1 year of age. This strategy was adopted, since the incremental cost of the 4th dose was higher than the 3rd dose.Citation76

United Kingdom: The Case of a 1p+1 Maintenance Program

In 2006, the UK introduced PCV7 into the universal NIP for infants with a 2p+1 schedule involving 2 primary doses at 2 and 4 months, followed by a booster dose at 12–13 months.Citation59,Citation77 Owing to high vaccine coverage (>90%) and herd immunity, a substantial reduction in PCV7-serotype-specific IPD cases, as well as overall IPD cases, was observed across all age groups.Citation78 Specifically, there was a 34% decline in the overall IPD incidence from 16.1 (2000–2006) to 10.6 (2009–10) per 100,000 people.Citation78 Following the replacement of PCV7 with the 13-valent conjugate vaccine in 2010, the incidence rate further declined to 6.85 per 100,000 in 2013–14 (more than 50% decline in incidence rate since PCV introduction).Citation79 However, IPD cases due to non-PCV13 serotypes increased in children <5 years and adults ≥45 years.Citation79 Currently, a maintenance 1p+1 schedule is used among infants that is sufficient to provide an appropriate level of immunity in children and the community.Citation59

Pneumococcal Disease and Immunization: The Iraq Scenario

Iraq is classified as a UMIC with a population of 40 million.Citation80 According to World Bank data for the year 2020, about 3% of the Iraqi population is >65 years of age.Citation81 Around 19% of the adult (≥18 years) population is affected by high blood pressure, 13% have raised blood glucose levels, and 27% are obese.Citation82 Furthermore, it has been estimated that 29–31% of the male and 3–4% of the female Iraqi population are active smokers.Citation83 Such factors place the Iraqi population at a high risk for developing pneumococcal disease. In fact, an estimated 111,636 total pneumococcal cases occurred in Iraq in 2015 ().Citation4,Citation5 Of these, a majority (79,601) were cases of pneumococcal pneumonia, with 31,294 being severe incidents. A total of 1954 pneumococcal deaths were reported in 2015, with 1669 caused due to pneumonia ().Citation4,Citation5 Adequate facilities for laboratory diagnosis of pneumococcal infections are not available in Iraq and cases are mostly diagnosed clinically and treated empirically. Further there is a lack of regular and effective surveillance of pneumococcal cases in the country which makes it difficult to provide an accurate disease burden data. Thus, these figures may not be an actual representation of the scenario in Iraq. The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was universally introduced into the NIP of Iraq in March 2017 () although its actual accessibility in the public sector remains a topic of debate. In 2021, PCV 13 became available in the private market and has been approved only for adults. shows that within the Eastern Mediterranean region, Iraq is one of the last few countries to have incorporated PCV, apart from Tunisia in 2019. The country currently uses the 13-valent PCV with a 3p+0 (3 primary doses at 2, 4, and 6 months of birth) dosing schedule.Citation5 The country has consistently recorded a very low WHO and UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC). In 2019, the WUENIC coverage was estimated at 37%, with about 1,077,376 children (data for 2020) remaining unvaccinated ().Citation5 In fact, within the Eastern Mediterranean region, Iraq is the only country (where PCV has been introduced) to have such a low coverage (). The current PCV vaccination status in Iraq warrants breaking this inertia in vaccine accessibility and coverage to harness the health, economic, and social benefits of immunization.

Barriers to Pneumococcal Vaccination in Iraq and Strategies to Overcome Them

Low education levels, lack of disease and vaccine awareness among people as well as health care providers (HCPs), concerns about side effects, and socioeconomic factors such as health care system delivery challenges have often been listed as barriers to vaccine acceptance.Citation84–87 In 1985, the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) was launched in Iraq with the aim of protecting mothers and children from several infectious diseases. The National Immunization Plan for 2015, jointly prepared with the United States Agency for International Development’s Primary Health Care Project in Iraq, listed several obstacles hindering the Iraqi EPI’s progress.Citation88 These include: (a) military operations and security complications, (b) power supply (fuel and electricity) shortage, (c) competing health priorities, (d) political difficulties that affect the Ministry of Health (MoH) plans and policies, (e) inadequate communication and coordination between the MoH and other directorates, (f) ill managed health care systems, (g) deficiencies in monitoring and supervision, (h) issues with vaccine transport, (i) financial barriers, (j) difficulty in reaching children in high-risk areas, and (k) a rapidly draining human resource capital for health care. Indeed, despite being a UMIC, the war and conflict situation in Iraq has led to fluctuations in vaccine coverage and associated disease outbreaks of several vaccine-preventable diseases.Citation89 The displacement of Iraqi people as a result of the war with poor health activities and overcrowding within camps provided a suitable habitat for the spread of several infectious diseases, including pneumococcal disease. Furthermore, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has strained the health care and immunization systems. According to the WHO, 23 million children across the globe were not able to get basic childhood vaccinations in 2020.Citation90 This disruption in the immunization program leaves children at the risk of developing preventable yet devastating infectious diseases and will also adversely affect the elderly and high-risk populations due to unmet herd immunity.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines are relatively expensive, as they have a complex manufacturing process. The estimated cost of global vaccinations with PCV is around US $16 billion per year.Citation91 In Iraq, PCV13 costs about US $18.77 per dose.Citation92 While these vaccines have been introduced in low-income countries at subsidized rates with the support of the GAVI, governments bear the cost of immunization in MICs from their national health care budgets. Analyzing the long-term budget implications, potential benefits, and cost-effectiveness of immunization becomes more crucial in such a scenario. It is documented that 54 of 85 MICs that do not qualify for GAVI support, have reported a stagnation or reduction in routine immunization levels since 2010.Citation93 As vaccination lags behind, the burden of unimmunized people is slowly shifting from LICs to MICs.Citation93 Several factors, such as the inefficient allocation of domestic resources, marginalized communities being ignored, and unstable health care systems, are responsible for such a situation.Citation93 In this scenario, the MICs need policies to strengthen existing health care systems and improve strategies for vaccine procurement and regulation. Furthermore, data access and surveillance technologies are crucial to determining who gets the vaccine and targeting at-risk and indigenous populations. Educating HCPs about the disease and vaccine is also essential, so that this preventive strategy becomes a priority in the care of high-risk patients. A motivational message from a community leader may be a strategy to increase awareness about this practice among the general public.Citation84 Social media can also act as a channel for creating awareness around immunization programs.Citation86 It has been observed that a shared decision-making process involving patient activation, the bidirectional exchange of information, and bidirectional deliberation is more likely to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates in adult patients in outpatient care.Citation94

Vaccine-related factors such as their cost-effectiveness and affordability are especially relevant in resource-constrained countries. The cost-effectiveness of PCV use depends on many factors, including the burden of disease, vaccine effectiveness, indirect effects, vaccination coverage, vaccine price, delivery costs and schedules.Citation95 The Iraqi MoH recently achieved an annual cost saving of US $70 million by modifying its childhood immunization schedule and procuring a greater number of vaccines via the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).Citation92 Such achievements are crucial to Iraq, where budget fluctuations frequently cause the exhaustion of vaccine stocks and are possible with transparent policy processes and strong leadership. The annual cost of the old schedule was US $129 million per year, whereas the new schedule amounts to US $59.7 million per year with PCV13 comprising a staggering 49% of the total annual cost.Citation92 The cost of vaccines should be set according to what countries can pay. PCV costs are around 8 times higher in MICs than in countries under GAVI support, although a lot of these MICs do not have commensurately higher gross national incomes.Citation93 The COVID-19 crisis has worsened the situation for several economies. In Iraq, the combined impact of the pandemic and the tumbling oil prices has led to an economic crisis with several Iraqis being pushed into poverty making them more susceptible to diseases due to lack of adequate nutrition and hygiene.Citation96 In this regard, cost-effective PCV alternatives may be more beneficial for UMICs such as Iraq. Additionally, the accessibility of the vaccine in the public sector should be ensured so that citizens are able to get free immunizations in a country that is facing economic challenges. Additionally, support may be taken from UNICEF or GAVI for procuring the vaccine at subsidized prices. Further, when using higher valent PCV13, a 2p+1 schedule might be more beneficial, considering WHO reports of higher seropositivity when using this dosage design instead of 3p+0.Citation9 Looking at the high pneumococcal disease burden in Iraq, the higher valent PCVs (PCV15 and PCV20) may be introduced in the country to target the high-risk adults (19–64 years) and the elderly population (≥64 years).

Recently, a Phase III clinical trial (sponsor: Pfizer) was conducted in the USA to study the coadministration of Prevnar 20® with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in adults ≥65 years.Citation97 The vaccines were coadministered to 570 adults. Responses produced by the pneumococcal vaccine were similar irrespective of coadministration with the COVID-19 vaccine or with a placebo. The response to a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine was also similar upon administration with Prevnar 20® or placebo. Such a strategy of coadministration of vaccines can be particularly beneficial to improving vaccine coverage in adult populations.

Conclusion

The incidence of pneumococcal disease development is determined by several factors, including age, immune status, and the socioeconomic status of countries. Apart from cost-effective strategies such as sanitation, hygiene and nutrition, immunization is the most effective public health intervention strategy to prevent pneumococcal disease. In Iraq, the conflict situation is a major barrier to achieving the overall success of pneumococcal immunization. Overcrowding and poor sanitation practices in displacement camps provide the perfect setup for disease dissemination. Further, the existing economic crisis and poverty make people more susceptible to disease and unable to procure the costly PCV vaccine. Thus, ensuring its continued availability free-of-cost in the public sector is the primary step in controlling pneumococcal disease. Although the country has had consistently poor WUENIC coverage, the lack of sufficient published pneumococcal literature for this country masks the actual scenario. In the wake of the raging COVID-19 pandemic, pneumococcal vaccinations have attained a higher level of significance, since any inflammatory damage caused to the respiratory mucosa by S. pneumoniae may also harm the innate mucociliary mechanism of the lungs, paving the way for invasion by other respiratory pathogens such as coronaviruses.Citation98 Thus, remedial measures are essential to improve this lag in pneumococcal vaccine coverage in Iraq. Strategies and policies for improved surveillance systems and analysis of the surveillance data will aid in efficiently screening, targeting, and monitoring different sections of the population. Effective surveillance studies will also help to obtain a true picture of the disease burden in the country, so as to better control pneumococcal dissemination. Strategies and policies for sustainable vaccine procurement, storage, and delivery systems need to be strengthened. Increasing the PCV vaccine coverage among children by procuring the vaccine at subsidized rates through GAVI support or opting for low-cost vaccine alternatives may be beneficial for Iraq, which faces financial obstacles in the health care system. A combined vaccine delivery strategy can be a good way to improve coverage among the adult population. Policymakers should also address strategies to improve awareness within the community and among HCPs by giving speeches at public forums, and social media platforms, trainings, etc., so that there is co-involvement from both the community and HCPs to combat this vaccine-preventable disease.

Disclosure

Delan Ikram and Ali Al-Jabban are Pfizer employees. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Adivitiya, Rosario Vivek and Parima Desai from IQVIA, India for writing assistance and providing insights.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt11-pneumo.html. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal Disease. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/pneumococcal-disease. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease: global pneumococcal disease and vaccination. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/global.html. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e744–e757. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X

- VIEW-hub. International Vaccine Access Center [IVAC], Johns Hopkins Bloomberg school of public health. Available from: https://view-hub.org/. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, et al. Pneumococcal capsules and their types: past, present, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):871–899. doi:10.1128/CMR.00024-15

- Tregnaghi MW, Saez-Llorens X, Lopez P, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal nontypable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) in young Latin American children: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11(6):e1001657. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001657

- Drijkoningen JJ, Rohde GG. Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 5):45–51. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12461

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and children under 5 years of age: WHO position paper–February 2019. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2019;94(08):85–104.

- Lanks CW, Musani AI, Hsia DW. Community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):487–501. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.008

- Bentley SD, Aanensen DM, Mavroidi A, et al. Genetic analysis of the capsular biosynthetic locus from all 90 pneumococcal serotypes. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(3):e31. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020031

- Johnson HL, Deloria-Knoll M, Levine OS, et al. Systematic evaluation of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five: the pneumococcal global serotype project. PLoS Med. 2010;7(10):e1000348. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000348

- Balsells E, Guillot L, Nair H, Kyaw MH. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in children in the post-PCV era: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177113. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177113

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease: risk factors. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/clinicians/risk-factors.html. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Torres A, Blasi F, Dartois N, Akova M. Which individuals are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease. Thorax. 2015;70(10):984–989. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206780

- Klugman KP, Black S. Impact of existing vaccines in reducing antibiotic resistance: primary and secondary effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(51):12896–12901. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721095115

- Hilleman MR, Carlson AJ, McLean AA, Vella PP, Weibel RE, Woodhour AF. Streptococcus pneumoniae polysaccharide vaccine: age and dose responses, safety, persistence of antibody, revaccination, and simultaneous administration of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3(Suppl):S31–S42. doi:10.1093/clinids/3.supplement_1.s31

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. PNEUMOVAX 23 - pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/pneumovax-23-pneumococcal-vaccine-polyvalent. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Zangeneh TT, Baracco G, Al-Tawfiq JA. Impact of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines on the changing epidemiology of pneumococcal infections. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(3):345–353. doi:10.1586/erv.11.1

- Lecrenier N, Marijam A, Olbrecht J, Soumahoro L, Nieto Guevara J, Mungall B. Ten years of experience with the pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D-conjugate vaccine (Synflorix) in children. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(3):247–265. doi:10.1080/14760584.2020.1738226

- Serum Institute of India Pvt. Ltd. Pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (adsorbed) pneumosil (10-valent). Available from: https://www.seruminstitute.com/product_ind_pneumosil.php. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Prevnar 13. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/prevnar-13. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Vaxneuvance. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/vaxneuvance. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Prevnar 20. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/prevnar-20. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Bogaert D, De Groot R, Hermans PW. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(3):144–154. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7

- Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(6):355–367. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8

- O’Brien KL, Nohynek H. World Health Organization pneumococcal vaccine trials carriage working G. Report from a WHO working Group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(2):e1–e11. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000049347.42983.77

- Haraldsson A. Vaccine implementation reduces inequity. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):e1264–e1265. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30489-3

- Neal EFG, Nguyen CD, Ratu FT, et al. Factors associated with pneumococcal carriage and density in children and adults in Fiji, using four cross-sectional surveys. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231041. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231041

- Chan J, Nguyen CD, Dunne EM, et al. Using pneumococcal carriage studies to monitor vaccine impact in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2019;37(43):6299–6309. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.073

- Brooks LRK, Mias GI. Streptococcus pneumoniae’s virulence and host immunity: aging, diagnostics, and prevention. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1366. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01366

- Al-Sanouri T, Mahdi S, Khader IA, et al. The epidemiology of meningococcal meningitis: multicenter, hospital-based surveillance of meningococcal meningitis in Iraq. IJID Regions. 2021;1:100–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijregi.2021.10.006

- Al-Ansari F, Mirzaei M, Al-Ansari B, et al. Health risks, preventive behaviours and respiratory illnesses at the 2019 Arbaeen: implications for COVID-19 and other pandemics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3287. doi:10.3390/ijerph18063287

- World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Children: improving survival and well-being. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Pneumonia. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/pneumonia#tab=tab_1. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- G. B. D lower respiratory infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1191–1210. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30310-4

- Dagan R, Bhutta ZA, de Quadros CA, et al. The remaining challenge of pneumonia: the leading killer of children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(1):1–2. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182005389

- Isaacman DJ, McIntosh ED, Reinert RR. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in young children in Europe: impact of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and considerations for future conjugate vaccines. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(3):e197–209. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.010

- Roca A, Sigauque B, Quinto L, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children<5 years of age in rural Mozambique. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(9):1422–1431. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01697.x

- Farooqui H, Jit M, Heymann DL, Zodpey S. Burden of severe pneumonia, pneumococcal pneumonia and pneumonia deaths in Indian States: modelling based estimates. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129191. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129191

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease: fast facts you need to know about pneumococcal disease. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/about/facts.html. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Ferreira-Coimbra J, Sarda C, Rello J. Burden of community-acquired pneumonia and unmet clinical needs. Adv Ther. 2020;37(4):1302–1318. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01248-7

- Huang SS, Johnson KM, Ray GT, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost of pneumococcal disease in the United States. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398–3412. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.088

- Wroe PC, Finkelstein JA, Ray GT, et al. Aging population and future burden of pneumococcal pneumonia in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(10):1589–1592. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis240

- Brown JD, Harnett J, Chambers R, Sato R. The relative burden of community-acquired pneumonia hospitalizations in older adults: a retrospective observational study in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0787-2

- Tichopad A, Roberts C, Gembula I, et al. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71375. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071375

- Al Dallal SAM, Farghaly M, Ghorab A, et al. Real-world evaluation of costs of illness for pneumonia in adult patients in Dubai-A claims database study. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0256856. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256856

- Schuchat A. Pneumococcal Prevention Gets Older and Wiser. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1897–1898. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6133

- World Health Organization. Global market study, Pneumococcal Conjugate (PCV) and Polysaccharide (PPV) vaccines; 2020:6. Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/procurement/mi4a/platform/module2/Pneumococcal_Vaccine_Market_Study-June2020.pdf. Accessed 17, March, 2022.

- Stein KE. Thymus-independent and thymus-dependent responses to polysaccharide antigens. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(Suppl 1):S49–S52. doi:10.1093/infdis/165-supplement_1-s49

- Pletz MW, Maus U, Krug N, Welte T, Lode H. Pneumococcal vaccines: mechanism of action, impact on epidemiology and adaption of the species. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32(3):199–206. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.021

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children 5 years after conjugate vaccine introduction--eight states, 1998–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(6):144–148.

- Prymula R, Schuerman L. 10-valent pneumococcal nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae PD conjugate vaccine: synflorix. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8(11):1479–1500. doi:10.1586/erv.09.113

- Rodgers GL, Whitney CG, Klugman KP. Triumph of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: overcoming a common foe. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(12 Suppl 2):S352–S359. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa535

- Alderson MR, Sethna V, Newhouse LC, Lamola S, Dhere R. Development strategy and lessons learned for a 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PNEUMOSIL(R)). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(8):2670–2677. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1874219

- World Health Organization. Principles and considerations for adding a vaccine to a national immunization programme: from decision to implementation and monitoring; 2014:924150689X. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/111548. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Considerations for pneumococcal vaccination in older adults. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2021;23(11):217–228.

- Vaccine Knowledge Project. PCV (Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine). Available from: https://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/vk/pcv. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Edouard S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, Yezli S, Gautret P. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal carriage and the effect of various pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7415–7422. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.017

- Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, et al. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal transmission. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(1):e77–e111. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.005

- Alharbi NS, Al-Barrak AM, Al-Moamary MS, et al. The Saudi Thoracic Society pneumococcal vaccination guidelines-2016. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11(2):93–102. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.177470

- Muhoza P, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Diallo MS, et al. Routine vaccination coverage - worldwide, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(43):1495–1500. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7043a1

- Lu PJ, Hung MC, Srivastav A, et al. Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populations -United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(3):1–26. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7003a1

- UK Health Security Agency. Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPV) coverage report, England, April 2020 to March 2021; 2021:14. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1035189/hpr1921-ppv-vc.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Chapman R, Sutton K, Dillon-Murphy D, et al. Ten year public health impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in infants: a modelling analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(45):7138–7145. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.068

- Megiddo I, Klein E, Laxminarayan R. Potential impact of introducing the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into national immunisation programmes: an economic-epidemiological analysis using data from India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(3):e000636. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000636

- Haridy H, Wasserman M. PIN95 public health IMPACT of 10 YEARS of the 13 valent pneumococcal vaccine in Africa and the middle east in children UNDER 5 YEARS. Value Health. 2020;23:S560. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.936

- Glikman D, Dagan R, Barkai G, et al. Dynamics of severe and non-severe invasive pneumococcal disease in young children in Israel following PCV7/PCV13 introduction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(10):1048–1053. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002100

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/public/index.html#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20saw%20largeActive%20Bacterial%20Core%20surveillance%20data. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease: surveillance and reporting. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/surveillance.html. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, Whitney CG, Grijalva CG. U.S. hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):155–163. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209165

- Public Health Agency of Canada. National laboratory surveillance of invasive streptococcal disease in Canada-annual summary 2018; 2018. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/aspc-phac/HP57-4-2018-eng.pdf. Accessed 17, March 2022.

- De Wals P, Lefebvre B, Markowski F, et al. Impact of 2+1 pneumococcal conjugate vaccine program in the province of Quebec, Canada. Vaccine. 2014;32(13):1501–1506. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.028

- De Wals P, Lefebvre B, Deceuninck G, Longtin J. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease before and during an era of use of three different pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Quebec. Vaccine. 2018;36(3):421–426. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.054

- Caroline Q. Vaccination against pneumococcal infection in Canada. Педиатрическая фармакология. 2014;11(1):16.

- UK Department of Health. Pneumococcal: the green book of immunisation, chapter 25; 2020:1–13. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pneumococcal-The-green-book-chapter-25. Accessed March 20, 2022.

- Miller E, Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Slack MP, George RC. Herd immunity and serotype replacement 4 years after seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in England and Wales: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(10):760–768. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70090-1

- Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani SN, Sheppard CL, Slack MP, Miller E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):535–543. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70044-7

- The World Bank. Iraq. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/IQ. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- The World Bank. Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) – Iraq. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS?locations=IQ. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018; 2018:224. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514620. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Ibrahim BA, Al-Humaish S, Al-Obaide MAI. Tobacco smoking, lung cancer, and therapy in Iraq: current perspective. Front Public Health. 2018;6:311. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00311

- Rehm SJ, File TM, Metersky M, Nichol KL, Schaffner W. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases Pneumococcal Disease Advisory B. Identifying barriers to adult pneumococcal vaccination: an NFID task force meeting. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(3):71–79. doi:10.3810/pgm.2012.05.2550

- Abdulah DM. Prevalence and correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the general public in Iraqi Kurdistan: a cross-sectional study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(12):6722–6731. doi:10.1002/jmv.27255

- Care Evaluations. COVID-19 vaccination uptake: a study of knowledge, attitudes and practices of marginalized communities in Iraq; 2021. Available from: http://careevaluations.org/evaluation/covid-19-vaccination-uptake-A-study-of-knowledge-attitudes-and-practices-of-marginalized-communities-in-iraq/. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Luma AH, Haveen AH, Faiq BB, Stefania M, Leonardo EG. Hesitancy towards Covid-19 vaccination among the healthcare workers in Iraqi Kurdistan. Public Health Pract. 2022;3:100222. doi:10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100222

- United States Agency for International Development. National immunization plan of Iraq for 2015; 2014. Available from: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KD56.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Lafta R, Hussain A. Trend of vaccine preventable diseases in Iraq in time of conflict. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:130. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.31.130.16394

- World Health Organization. Immunization coverage. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Chen C, Cervero Liceras F, Flasche S, et al. Effect and cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a global modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e58–e67. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30422-4

- Hossain SMM, Hilfi RA, Rahi A, et al. Annual cost savings of US$70 million with similar outcomes: vaccine procurement experience from Iraq. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(2):e008005. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008005

- Berkley S. Vaccination lags behind in middle-income countries. Nature. 2019;569(7756):309. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01494-y

- Kuehne F, Sanftenberg L, Dreischulte T, Gensichen J. Shared decision making enhances pneumococcal vaccination rates in adult patients in outpatient care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9146. doi:10.3390/ijerph17239146

- Chaiyakunapruk N, Somkrua R, Hutubessy R, et al. Cost effectiveness of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: a comparative assessment of decision-making tools. BMC Med. 2011;9:53. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-53

- UNICEF. Assessment of COVID-19 Impact on Poverty and Vulnerability in Iraq; 2020.

- Pfizer. positive top-line results of pfizer’s phase 3 study exploring coadministration of PREVNAR 20™ with Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in older adults released. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/positive-top-line-results-pfizers-phase-3-study-exploring-0. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Sultana J, Mazzaglia G, Luxi N, et al. Potential effects of vaccinations on the prevention of COVID-19: rationale, clinical evidence, risks, and public health considerations. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(10):919–936. doi:10.1080/14760584.2020.1825951