Abstract

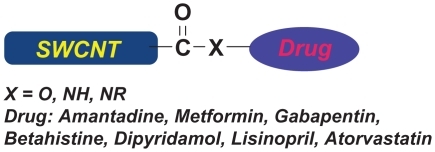

The grafting of drugs to the single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) was attained by the initial conversion of carboxylic groups in SWCNT to corresponding acyl chlorides. The active acyl chlorides in SWCNT were subsequently mixed with chemotherapeutic agents having NH, NH2, and OH functional groups to afford the formation of relevant amide and ester, respectively. The covalently grafted drugs to SWCNT were identified by infrared and UV–visible spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy methods. From a clinical aspect, the grafting of drugs to the SWCNT can be used as a new tool and useful method for potential drug delivery in patients.

Keywords:

Introduction

Slow release is critically significant in drug delivery for minimizing the amount of drug lost before reaching the target. Shell structures and supports can be used for slow delivery of drugs and are usually made from organic materials. For example, liposomes,Citation1–Citation3 microspheres,Citation4 polymeric shells,Citation5 and polymeric micellesCitation6,Citation7 have been well investigated. In constructing a drug delivery system from organic materials, the combinations of shell or support materials, targeting molecules, and drugs are restricted to ensure stability, targeting efficiency, and drug effect. Although, many supporting polymers are expensive, this restriction can be reduced by using carbon nanotubes (CNTs).Citation8 On the other hand, nanomedicine, which is an emerging bridge linking nanotechnology and advanced medical technology, involves the exploration of nanoscaled materials with the aim of developing novel types of drug carriers, imaging agents, sensors, etc.Citation9,Citation10

Nanotubes have several properties that make them suitable for use as nanotube-supported drugs. Functionalized CNTs have been shown in many studies to be able to cross cell membranes.Citation11–Citation13 The ability of CNTs to cross cell membranes allowing them to be used as carriers is of particular high interest for drug delivery strategies. In targeting the delivery of drugs to cells, the drugs are first attached to the carrier by either covalent or noncovalent bonding. The drug carrier conjugates are then directed to the targeted cells via passive targeting methods (ie, a methodology to increase the target/nontarget ratio of the amounts of drugs delivered primarily by minimizing nonspecific interactions with nontarget organs, tissues, and cells) or active targeting methods (ie, the method by which the therapeutic agent is delivered to tumors by attaching the agent with a ligand that binds to specific receptors that are overexpressed on target cells).Citation14 After reaching the targeted site (organs, tissues, or cells), there are 2 possibilities: (1) the drug is internalized (ie, enters the cells) without internalization of the carrier or (2) both the drug and the carrier are internalized. The latter internalization method has greater delivery efficacy because after entering the cells, the intracellular environment will degrade the drug–carrier conjugate, releasing drug molecules inside the cells. On the other hand, in the former internalization method, the extracellular environment helps degrade drug–carrier conjugates, and the drug will then cross the lipid membrane to enter the cells. CNTs with the ability to cross cell membranes are good candidates to serve as drug delivery carriers to cells with high efficacy.Citation15 Also, negative mutagenic and clastogenic potentials suggest that single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and single-walled carbon nanohorns (SWCNHs) are not carcinogenic. For example, the acute per oral toxicity of SWCNHs was found to be quite low.Citation16–Citation18 The lethal dosage for rats was more than 2,000 mg/kg of body weight. Intratracheal instillation tests revealed that SWCNHs rarely damaged rat lung tissue in a 90-day test period, although black pigmentation due to the accumulation of SWCNHs was observed.Citation19 In recent years, biological applications for carbon nanomaterials, including SWCNHs and fullerene, have come under close scrutiny.Citation11,Citation20–Citation24

SWCNHs and SWCNTs have extensive surface areas. Multitudes of horn interstices in SWCNHs enable large numbers of guest molecules to be adsorbed in a nonbonded way; however, to the best of our knowledge, the covalent grafting of drugs to the SWCNT has not been reported so far. Herein, we report the ability of SWCNTs for the covalent grafting of drugs to their active sites ().

The medicinal standpoint of this present research is covalent grafting of drugs to SWCNTs, which can be considered a new method for potential drug delivery. This would be achievable by preparing several pastes that can be applied on the skin similar to a label. Hydrolysis reaction occurs, and the drug is absorbed through the skin long time intervals after the application of the paste.Citation25 This process, therefore, enables the slow administration of medications for longer periods. This can help patients who have problems associated with oral administration and injection of drugs.

The solubility of products obtained in this work is also an important subject. The solubility of SWCNTs in aqueous and organic solvents has been previously studied by functionalizing the SWCNTs with various organic moieties.Citation26

Materials and methods

Materials

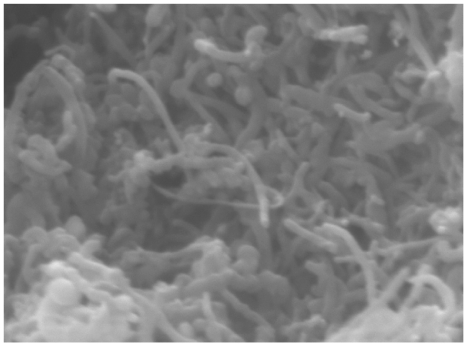

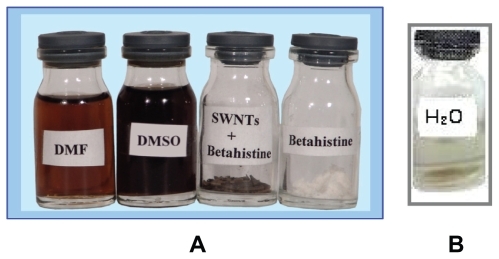

The pure SWCNTs in their closed cap shape without functional groups were purchased from Petrol Co. (Tehran, Iran) (). SOCl2, HCl, H2SO4, HNO3, H2O2 (30 wt%, aq), deionized water, NaH (80%), anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF), CaH2, anhydrous Na2SO4, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH = 1.3) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich and Merck. Cellophane membrane dialysis bag was purchased from Polymer Co. (Tehran/Iran). Drugs, such as amantadine, metformin, gabapentin, betahistine, dipyridamol, lisinopril, and atorvastatin, were purchased from Sobhan Darou Co. (Tehran, Iran).

Functionalization of SWCNTs

To functionalize the SWCNT with drugs having amino and/ or hydroxyl moieties, we followed a methodology already demonstrated by several literatures.Citation26–Citation30

The first step was cracking and oxidation of the SWCNTs. For every 0.1 g of full-length SWCNT, 50 mL mixture of 3:1 (vol/vol) concentrated H2SO4 and HNO3 was added, and the SWCNT–acid mixture was then subjected to reflux at temperature between 65°C and 70°C for 30 hours.

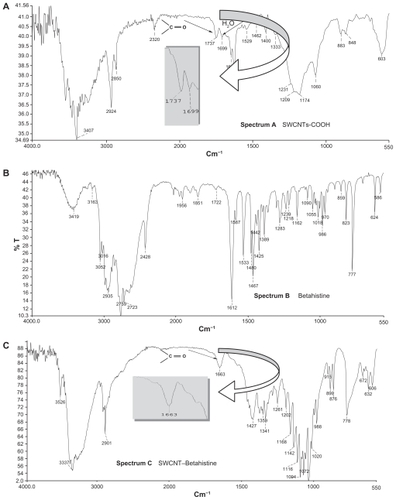

When the desired time had elapsed, the SWCNT–acid mixture was diluted with a minimum amount of deionized water (250 mL). The resulting diluted nanotube–acid mixture was then filtered using a 0.45 μm polytetrafluoro- ethylene filter (PTFE–millipore) to leave a SWCNT filter cake. The nanotubes were then rinsed with water until a pH above 5 was obtained. Final rinsing was done using ethanol, and the resulting filter cake was suspended in a 4:1 mixture of H2O2 (30 wt%, aq) and H2SO4. The suspension was refluxed for 2 hours at 70°C to crack the SWCNTs in shorter lengths and, thereby, produce a larger number of opened caps for carboxylation. Concentrated HCl was then added to the suspension and briefly sonicated to remove the metal catalyst,Citation27–Citation29 which resulted in the introduction of terminal carboxyl functional groups, as indicated by infrared measurement (ν(C=O) = 1,737 cm−1; spectrum A, ). The precipitate was stored in a vacuum oven at 180°C to remove the water.

Figure 3 Solubility of grafted SWCNT–betahistine A) in dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and B) in H2O.

The second step was the generation of the acyl chloride functional groups by suspending the purified SWCNT (prepared from the first step) in a solution of freshly distilled thionyl chloride (SOCl2) and DMF, which was previously kept in anhydrous Na2SO4 for 72 hours and distilled in the presence of CaH2. The amounts used in this particular example were 20 mL SOCl2 and 1 mL DMF per 0.1 g of SWCNT. This suspension was stirred at 65°C for 24 hours. The solid was then separated by filtration and washed with superdried tetrahydrofuran (THF) to remove excess of SOCl2. Subsequently, it was dried in vacuum at room temperature for 5 minutes. The final product was then subjected to functionalization with various drugs.

Drugs having free OH, NH2, or NH groups (drug-to- SWCNT weight ratio was 15:1)Citation30 were mixed with 1 mL solution of DMF and NaH (80%) and then stirred for 1 hour. The obtained acyl chloride SWCNTs were then added to the suspension. The reaction mixture was kept at 120°C for 5 days. The solid was then separated by filtration and washed with deionized water for several times.

The reaction of the drugs with SWCNT and the potential structure of grafted drugs to SWCNTs are summarized in .

Table 1 Covalent grafting of various drugs to SWCNT

After stirring, a black solid was obtained, which was soluble in DMF and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), less soluble in H2O and CH3CN, and insoluble in CHCl3, CH2Cl2, acetone, diethyl ether, and hexane ().

Results and discussion

We characterized the functional groups present in the covalent drugs grafted to SWCNT by IR and UV–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) methods after various treatments.

After the initial acid treatment of SWCNT with a mixture of H2SO4 and HNO3 followed by HCl, the spectrum A was observed (). The IR spectrum B is pertaining to pure betahistine, and the IR spectrum C () shows the grafted SWCNT–betahistine (entry 4b, ). The band corresponding to the carboxylic groups present in the acid-treated SWCNT (1,737 cm−1; IR spectrum A, ) is gradually replaced by bands corresponding to amide bonds (1,663 cm−1; IR spectrum C, ). Band at 1,699 cm−1 is attributed to water (IR spectrum A, ). summarizes the main bands observed in IR spectra of grafted drugs to SWCNTs.

Table 2 Infrared absorption bands obtained from the acid-treated SWCNTs and drugs grafted to SWCNTs’ solid samples

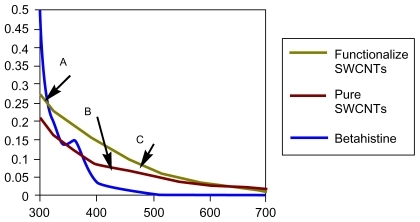

The UV–vis absorption spectrum of betahistine () displays a loss of features compared with that of SWCNT indicating a disruption in the electronic structure of nanotubes due to the adsorption of betahistine on SWCNT.

Figure 5 Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of A) betahistine in dimethylformamide (DMF), B) pure SWCNTs and, C) grafted SWCNT–betahistine (functionalized SWCNTs).

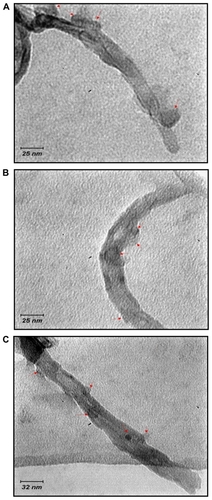

TEM studies have revealed the successful grafting of betahistine and other drugs to SWCNT (). A large number of the bundles are abundant in functionalized SWCNTs, which are indicated by arrows.

Figure 6 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of A) grafted SWCNT– betahistine, B) grafted SWCNT–dipyridamol, and C) grafted SWCNT–lisinopril (, entries 4b–6b). The arrows indicate the grafted drugs to SWCNT.

In vitro release of betahistine from grafted SWCNT–betahistine

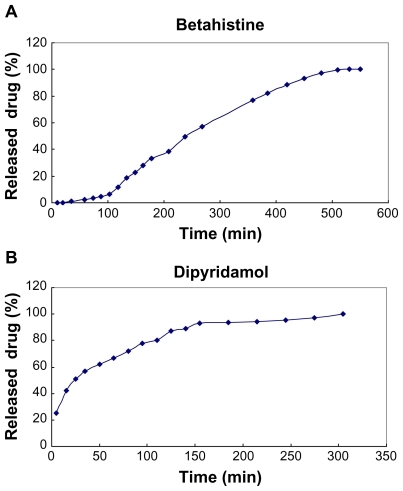

Drug releasing from the grafted SWCNT–drug is indeed a hydrolysis reaction, which involves breaking of amide bond in acidic buffer (PBS; pH = 1.3) at 37°C. The powdered grafted SWCNT–betahistine (0.02 g) was added into a cellophane membrane dialysis bag. The bag was closed and transferred into a flask containing 50 mL of acid buffer. The release of betahistine from grafted SWCNT–betahistine was followed by UV–vis spectroscopy. illustrates the cumulative dose of betahistine released from grafted SWCNT–betahistine.

Drug loading of betahistine

A weighed quantity of microspheres was hydrolyzed in 50 mL acid buffer (PBS; pH = 1.3). After suitable dilution, the absorbance of samples was measured by UV–vis spectrophotometer at λ = 264 nm. The amount of drug was determined from the standard plot of betahistine. The amount of betahistine loaded in SWCNTs’ microspheres was determined after complete hydrolysis and was found to be 73 wt%.

In vitro release of dipyridamol from grafted SWCNT–dipyridamol

The release of dipyridamol from the grafted SWCNT– dipyridamol was studied using the same method, which has been described earlier for SWCNT–betahistine. illustrates the cumulative dose of dipyridamol released from grafted SWCNT–dipyridamol.

Drug loading of dipyridamol

Drug loading of dipyridamol (λ = 262 nm was studied using the same method, which has been described earlier for SWCNT–betahistine, and was found to be 65 wt%. It is interesting to note that the release of dipyridamol from SWCNTs was achieved more smoothly than that of betahistine from SWCNT–betahistine. This can be easily deduced by comparing with .

Conclusion

In summary, the covalent grafting of some known drugs with different pharmaceutical activities to SWCNTs was achieved by the formation of amides and esters from the drugs having free hydroxyl and/or amino groups mixed with the prepared acyl chloride in SWCNTs. The covalent grafting of drugs increases the solubility of SWCNTs in both aqueous and organic solvents. In vitro release of betahistine and dipyridamol from their corresponding grafted SWCNT adducts was studied, which indicates that drug release can occur smoothly from covalent SWCNT–drug adducts during long time intervals, and this can be considered a useful method for drug delivery.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support from Bu-Ali Sina University Research Council and Center of Excellence in Development of Chemical Methods (CEDCM) for their work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- YatvinMBWeinsteinJNDennisWHBlumenthalRDesign of liposomes for enhanced local release of drugs by hyperthermiaScience19782021290364652

- AllenTMLiposomal drug formulations. Rationale for development and what we can expect for the futureDrugs1998567479829150

- BurgerKNJStaffhorstRWde VijlderHCNanocapsules: lipid-coated aggregates of cisplatin with high cytotoxicityNat Med200288111786911

- MatsumotoAMatsukawaYSuzukiTYoshinoTKobayashiMThe polymer-alloys method as a new preparation method of biodegradable microspheres: principle and application to cisplatin-loaded microspheresJ Control Release19974819

- MaedaHSawaTKounoTMechanism of tumor-targeted delivery of macromolecular drugs, including the EPR effect in solid tumor and clinical overview of the prototype polymeric drug SMANCSJ Control Release2001744711489482

- YokoyamaMMiyauchiMYamadaNCharacterization and anticancer activity of the micelle-forming polymeric anticancer drug adriamycin-conjugated poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(aspartic acid) block copolymerCancer Res19905016932306723

- NishiyamaNOkazakiSCabralHNovel cisplatin-incorporated polymeric micelles can eradicate solid tumors in miceCancer Res200363897714695216

- IijimaSDiscovery of multi-wall carbon nanotubesNature199135456

- MoghimiSMHunterACMurrayJCNanomedicine: current status and future prospectsFASEB J20051931115746175

- FerrariMCancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challengesNat Rev Cancer2005516115738981

- PantarottoDBriandJPPratoMBiancoATranslocation of bioactive peptides across cell membranes by carbon nanotubesChem Commun20041617

- Shi KamNWJessopTCWenderPADaiHNanotube molecular transporters: internalization of carbon nanotube protein conjugates into mammalian cellsJ Am Chem Soc20041266850685115174838

- KamNWSO’ConnellMWisdomJADaiHCarbon nanotubes as multifunctional biological transporters and near-infrared agents for selective cancer cell destructionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2005102116001160516087878

- TranPAWebsterTJDixonCJCurtinesOWNanotechnologies for cancer diagnostics and treatmentNanotechnology: Nanofabrication, Atterning, and Self AssemblyNew York, NYNova Publishers2009 In press

- PhongATZhangLWebsterTJCarbon nanofibers and carbon nanotubes in regenerative medicineAdv Drug Deliv Rev2009610971114

- ConstantinePFPrabhakarRBToxicity issues in the application of carbon nanotubes to biological systemsNanomedicine2010624525619699321

- BottiniMBrucknerSNikaKMulti-walled carbon nanotubes induce T lymphocyte apoptosisToxicol Lett200616012112616125885

- ShvedovaAAKisinERPorterDMechanisms of pulmonary toxicity and medical applications of carbon nanotubes: two faces of JanusPharmacol Ther200912119220419103221

- MiyawakiJYudasakaMAzamiTKuboYIijimaSToxicity of single-walled carbon nanohornsACS Nano2008221319206621

- YangZZhangYYangYPharmacological and toxicological target organelles and safe use of single-walled carbon nanotubes as drug carriers in treating Alzheimer diseaseNanomedicine20106342744120056170

- ZhangXMengLLuQFeiZDysonPJTargeted delivery and controlled release of doxorubicin to cancer cells using modified single wall carbon nanotubesBiomaterials200930604119643474

- KlumppCKostarelosKPratoMBiancoAFunctionalized carbon nanotubes as emerging nanovectors for the delivery of therapeuticsBiochim Biophys Acta2006175840416307724

- PantarottoDPartidosCDHoebekeJImmunization with peptidefunctionalized carbon nanotubes enhances virus-specific neutralizing antibody responsesChem Biol20031096196614583262

- ParkKHChhowallaMIqbalZSestiFSingle-walled carbon nanotubes are a new class of ion channel blockersJ Biol Chem2003278502125021614522977

- WilsonCOGisvoldOBlockJHWilson and Gisvold’s Textbook of Organic Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry11th edPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams and Wilkins2004

- NiyogiSHamonMAZhaoBChemistry of single-walled carbon nanotubesAcc Chem Res200235110512484799

- FuKHuangWLinYRiddleLACarrollDLSunYPDefunctionalization of functionalized carbon nanotubesNano Lett20011439

- MarshallMWPopa-NitaSShapterJGMeasurement of functionalised carbon nanotube carboxylic acid groups using a simple chemical processCarbon2006441137

- KimWJKangSOAhCSFunctionalization of shortened SWCNTs using esterificationBull Korean Chem Soc2004259

- PompeoFResascoDEWater solubilization of single-walled carbon nanotubes by functionalization with glucosamineNano Lett20022369