Abstract

Rosette nanotubes (RNTs) are novel, biomimetic, injectable, self-assembled nanomaterials. In previous studies, materials coated with RNTs have significantly increased cell growth (eg, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and endothelial cells) due to the favorable cellular environment created by RNTs. It has also been suggested that the tubular RNT structures formed by base stacking and hydrophobic interactions can be used for drug delivery, and this possibility has not been studied to date. Here we investigated methods to load and deliver tamoxifen (TAM, a hydrophobic anticancer drug) using two different types of RNTs: single- base RNTs and twin-base RNTs. Drug-loaded RNTs were characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, diffusion-ordered nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (DOSY NMR), and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy at different ratios of twin-base RNTs to TAM. The results demonstrated successful incorporation of hydrophobic TAM into RNTs. Importantly, because of the hydrophilicity of the outer surface of the RNTs, TAM-loaded RNTs were dissolved in water, and thus have great potential to deliver hydrophobic drugs in various physiological environments. The results also showed that twin-base RNTs further improved TAM loading. Therefore, this study demonstrated that hydrophobic pharmaceutical agents (such as TAM), once considered hard to deliver, can be easily incorporated into RNTs for anticancer treatment purposes.

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in the use of injectable, biocompatible, biodegradable polymersCitation1–Citation5 and nanoparticlesCitation6 for anticancer drug delivery applications. Methods based on external stimuli (ie, ultraviolet light for crosslinking) to create amphiphilic polymersCitation7 or lipid drug mixturesCitation6 to deliver water-insoluble anticancer drugs seek to improve drug solubility in water, increase drug bioavailability, and decrease drug toxicity.Citation8 In addition, molecules with self-assembly properties have been studied for such applications.Citation9–Citation11 However, complex, chemical treatments used to create some of these drug carriers can result in a reduction of drug efficacy.Citation12,Citation13 Also, many simpler mixtures provide a fast, uneven release of hydrophobic drugs under physiological conditions, thus limiting prolonged cell–drug interactions.Citation14,Citation15

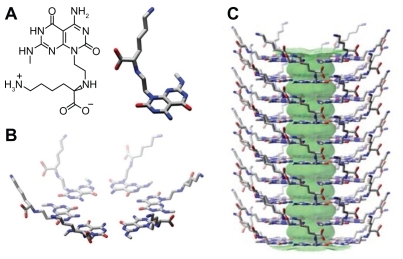

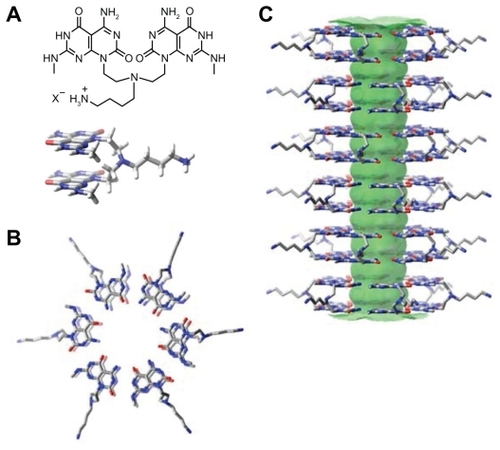

In order to avoid such ineffective, complex drug carrier designs, and ensure solubility of water-insoluble drugs, rosette nanotubes (RNTs) have been developed and have shown to be advantageous in regenerative medicine due to their biologically-derived structure and chemical properties. RNTs are novel, biomimetic, synthetic, self-assembled nanomaterials. Structurally, RNTs have hollow channels that can be used for drug encapsulation. To date, there have been two types of RNTs, ie, single-base RNTs such as K1 (K=lysine; ) and twin-base RNTs such as twin-base linker molecules (TBLs) (). Both types of RNTs are composed of self-assembled supramolecular structures, the basic building blocks of which are guanine (G) and cytosine (C) DNA base pairs.Citation16–Citation19 The G^C heteroaromatic bicyclic base of RNTs possess the Watson–Crick donor–donor–acceptor of guanine and the acceptor– acceptor–donor of cytosine. For K1, G^C undergoes a hierarchical self-assembly process under physiological conditions to form a six-member rosette (ie, supermacrocycle) by the formation of 18 hydrogen bonds. A lysine side chain is used for solubility, biocompatibility, and for imposing supramolecular chirality. In the case of TBL, two covalently connected G^C bases self-assemble into a 6-member twin rosette maintained by 36 hydrogen bonds. For both types of RNTs, the rosettes form a stable stack with an inner diameter of 11 Å due to dispersion forces, base stacking interactions, and hydrophobic effects. The outer diameters for K1 and TBL are 3.5 nm and 3.8 nm, respectively ( and , respectively).

Figure 1 Schematic illustration of the hierarchical assembly of K1 with a lysine side chain. A) The G^C motif functionalized with a lysine side chain. B) Six G^C motifs self-assemble into a rosette supermacrocycle by the formation of 18 hydrogen bonds, and C) The rosettes stack up to form a stable 3.5 nm diameter RNT with an 11 Å inner channel.

Abbreviations: C, cytosine; G, guanine; K, lysene; RNT, rosette nanotubes.

Figure 2 Schematic illustration of the hierarchical assembly of TBLs. A) The twin G^C motif functionalized with an aminobutyl group. B) Six twin G^C motifs self-assemble into a twin rosette supermacrocycle held by the formation of 36 hydrogen bonds. C) The rosettes stack up to form a stable 3.8 nm diameter TBL with an 11 Å inner channel.

Abbreviations: TAM-Kl, tamoxifen encapsulated in K1; TAM-TBL, tamoxifen encapsulated in TBL.

RNTs may be able to deliver hydrophobic drugs for a number of reasons. The self-assembly of RNTs creates a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic outer surface. Thus, RNTs are able to incorporate water-insoluble drugs into their tubular structures by hydrophobic interactions with the core whereas their hydrophilic outer surface can shield such hydrophobic drugs in a physiological environment for subsequent prolonged release (even into the cell). RNTs could also be chemically functionalized with peptides to deliver growth factors for healthy tissue regeneration after the delivery of drugs to kill cancer cells. For example, previous studies have shown that hydrogels coated with Arg–Gly–Asp–Ser–Lys modified RNTs improved osteoblast growth compared with unmodified hydrogels, thus making them attractive to potentially regenerate healthy bone in osteosarcoma patients.Citation20 It has also been shown that RNTs are biocompatible and are able to enhance protein adsorption, cell adhesion, and subsequent cell functions.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 Thus, it is conceivable that the RNTs could not only improve healthy cell and tissue growth, but may also deliver hydrophobic drugs to target areas.

Due to its hydrophobic properties and delivery problems, the drug selected for this study was tamoxifen (TAM), a water-insoluble anticancer drug used in the treatment of patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer.Citation22 In this study, TAM was incorporated into two types of RNTs, ie, K1 and TBL. Successful incorporation was verified using diffusion-ordered nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (DOSY NMR) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. Subsequent comparison between the two types of RNTs showed that the more stable TBL enabled more TAM loading. Therefore, this study demonstrated that RNTs are potential drug delivery devices for water-insoluble drugs, such as TAM, and should be further studied as anticancer coatings on medical devices or as stand-alone injectable anticancer drugs.

Materials and methods

Preparation of K1 and TBL

K1Citation18 (RNT with a lysine side chain) and TBLCitation19 were synthesized according to previously reported procedures.

Characterization of TAM-loaded K1 and TBL

K1 building block (4.30 mg) was first dissolved in deuterated methanol (CD3OD, 1 mL) and aged for 1 day. t-BuOH (3 μL) (≥99.5%, anhydrous; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added as an internal standard to quantify, by 1H-NMR, the extent of TAM (T5648; Sigma) association with the RNTs. TAM (5 mg) was then added, thus resulting in a solution with a 5:3 TAM:K1 molar ratio. The solution was aged for two days to allow for the drug-loading process, and the supernatant was isolated for subsequent 1H-NMR studies. Other solutions with 5:1 and 5:5 TAM:K1 molar ratios were also prepared. The TBL building block (3 mg) was dissolved in CD3OD (1 mL) and the same procedure was followed to prepare mixtures with TAM (1.53 mg) resulting in a solution with a 5:5 molar ratio of TAM:TBL.

The supernatants were characterized by DOSY NMR and UV-Vis. 1H-NMR was used to observe the amount of drug loaded into the RNTs at various time points. All the NMR experiments were conducted on a Varian Direct Drive 600 MHz spectrometer with a dual broadband probe. UV-vis spectra were recorded on an Agilent 8453. After this series of spectral analyses was completed, CD3OD was evaporated using a stream of nitrogen and replaced with the same volume of deuterated water (D2O). Any hydrophobic TAM that was not incorporated into the nanotubes precipitated in D2O and was filtered out prior to NMR studies.

The NMR peaks corresponding to the drug were monitored and their integration was compared to the internal standard to determine the amount of encapsulated versus free drug in CD3OD. Under the same experimental conditions, DOSY NMR was performed to detect subtle changes in the diffusion coefficients of TAM in the presence of K1 and TBL.

For UV-Vis experiments, the supernatants of the drug-loaded K1 and TBL were diluted with methanol to a final concentration of 25 μg/mL of TAM. In addition, three other solutions were prepared, ie, 5 μg/mL TAM, 25 μg/mL K1, and 25 μg/mL TBL. Each solution (3 mL) was placed in a 1 cm ×1 cm cuvette for UV-Vis experiments. In another series of experiments the solutions were prepared at the same concentration in D2O and analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy. Because TAM was insoluble in D2O, no corresponding peak was recorded. Peaks from TAM and TAM-K1 were compared with those from TAM and TAM-TBL.

Sample preparation of TAM-loaded K1 and TBL for atomic force microscopy

For atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments, samples prepared in D2O were diluted to 25 μg/mL and imaged using a MultiMode Nanoscope IV AFM (Digital Instruments/ Veeco Instruments, New York, NY) equipped with an E scanner. Height profiles were measured using silicon cantilevers (MikroMasch USA, Inc., Portland, OR) with low spring constants of 4.5 N/m in tapping mode. To obtain a clear image of the surface, a low scan rate (0.5–1 Hz) and amplitude setpoints (1 V) were chosen during measurements. Citation19 Clean mica substrates (Mica-Grade V-4 SPI, Catalog number 01918-CF and Lot number 1100315) were prepared and the samples were deposited by spin-coating 20 μL of each solution at 2000 rpm for 20 seconds.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as standard error of the mean. Statistics were performed using a Student’s one-tailed t-test, with P < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

Because of their large molecular weight and long relaxation time, K1 and TBL were not detected by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Thus as the drug becomes encapsulated by the RNTs, its integration by 1H-NMR decreases relative to the internal standard (t-BuOH). At the TAM:K1 molar ratio of 5:3 (),

Table 1 1H-NMR spectroscopy of TAM-K1 mixture (5:3 molar ratio) at different time intervals monitored at 7.25 ppm

Results also showed that more TAM was incorporated as additional K1 was added ().

Table 2 1H-NMR spectroscopy of TAM-K1 and TAM-TBL at different molar ratios monitored at 2.68–3 ppm

Interestingly, the more stable and more hydrophobic TBL incorporated a slightly larger amount of TAM relative to K1 (11.3% ± 2.1% greater loading), as shown in . To provide further evidence for the incorporation of TAM into K1 and TBL, changes in the diffusion coefficient of TAM obtained from the DOSY NMR experiments ( and ) were measured and were found to vary from 7.27 to 5.37 for K1, and from 7.27 to 5.48 for TBL. This reduction in diffusion coefficient is indicative of an interaction between the drug and the larger RNT assemblies.

Table 3 DOSY NMR of TAM and of TAM-K1 mixture (5:5 molar ratio)

Table 4 DOSY NMR of TAM and of TAM-TBL mixture (5:5 molar ratio)

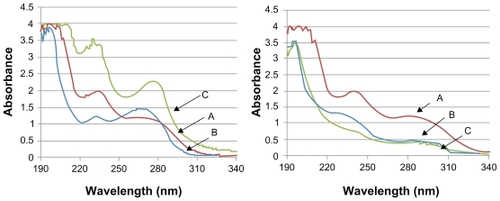

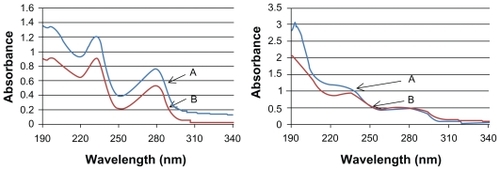

Incorporation of TAM in K1 and TBL was also investigated by UV-Vis experiments (), which showed significantly different profiles for TAM-K1 and TAM-TBL in methanol. When the UV-Vis spectra were recorded in water, which mimics the actual physiological environment in the body, the UV-Vis profiles of K1 and TBL were significantly different from those of TAM-K1 and TAM-TBL, respectively. This result indicated once again that TAM does bind to the RNTs.

Figure 3 UV-Vis spectra recorded in methanol of A) TAM (5 μg/mL), B) K1 (left) and TBL (right) (25 μg/mL), C) TAM-K1 (left) and TAM-TBL (right) (25 μg/mL).

Abbreviations: K1, rosette nanotubes with lysine; TAM, tamoxifen; TAM-K1, tamoxifen encapsulated in K1; TAM-TBL, tamoxifen encapsulated in TBL.

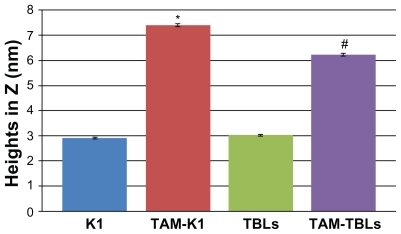

Tapping mode AFM () showed different heights for the aqueous solutions of RNTs in the presence and in the absence of TAM. Height measurements showed a significantly greater value for RNT-encapsulated TAM (). The average heights were 2.91 nm, 7.40 nm, 3.02 nm, and 6.22 nm for K1, TAM-K1, TBL, and TAM- TBL, respectively. While the values for the complexes are dramatically high relative to the uncomplexed RNTs, they do support the existence of an interaction between drug and RNTs (whose exact nature is still unknown at this stage).

Figure 4 UV-Vis spectra recorded in water of A) TAM-K1 (left) and TAM-TBL (right), and B) K1 (left) and TBL (right). All samples were at a concentration of 25 μg/mL.

Abbreviations: K1, rosette nanotubes with lysine; TAM, tamoxifen; TAM-K1, tamoxifen encapsulated in K1; TAM-TBL, tamoxifen encapsulated in TBL.

Figure 5 Tapping mode AFM height images of A) K1, B) TAM-K1, C) TBL, and D) TAM-TBL.

Abbreviations: K1, rosette nanotubes with lysine; TAM, tamoxifen; TAM-K1, tamoxifen encapsulated in K1; TAM-TBL, tamoxifen encapsulated in TBL.

Figure 6 Quantitative height measurements by atomic force microscopy.

Notes: Data are mean ± standard error of mean (more than 30 random points were chosen from atomic force microscopy scans). *P < 0.05 compared with K1 only; #P < 0.05 compared with TBL only.

Abbreviations: K1, rosette nanotubes with lysine; TAM, tamoxifen; TAM-K1, tamoxifen encapsulated in K1; TAM-TBLs, tamoxifen encapsulated in TBLs, TBLS, twin base linkers.

Discussion

The drug-loading capacity of K1 and TBL was investigated here for the first time under various conditions using 1H-NMR. For equivalent concentrations of TAM and RNTs, ca. 30% of the hydrophobic anticancer drug was incorporated. The amount of RNTs present was crucial to how much TAM could be loaded. Successful TAM loading was further confirmed by DOSY NMR experiments where diffusion coefficients of TAM diminished significantly after interacting with the RNTs. UV-Vis experiments supported the presence of an interaction between TAM and RNTs. Although our experiments did not establish how TAM molecules may be incorporated into the RNTs, the hypochromic effect observed in the UV-Vis spectra of TAM-TBL suggests that TAM molecules may be intercalating between the G^C bases. Furthermore, AFM height profiles showed a dramatic increase in RNT cross-section as a result of interaction with TAM. It should also be noted the RNTs maintained their structural integrity after TAM loading, which has been shown to be essential for their biological activity.Citation20

TAM is widely used as an anticancer drug, but its water insolubility has limited its delivery and release in physiological environments. Previous studies have investigated drug delivery systems for hydrophobic drugs.Citation23,Citation24 A variety of water-insoluble drugs have been incorporated in biodegradable polymers, eg, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid [PLGA]) and nonbiodegradable polymers, eg, poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate, EVAc).Citation25,Citation26 However, several issues associated with these polymers have been raised such as the presence of residual organic solvents, toxicity of photoinitiators, and complex material preparation.Citation25,Citation27 For example, PLGA is one of the most widely used drug delivery agents, but its acidic degradation byproducts (lactic acid and glycolic acid) possess some degree of cytotoxicity. Citation28 In addition, some studies have found that the organic solvents used in the formulation of PLGA (eg, CH2Cl2), still present in trace amounts, could negatively influence surrounding cells and tissues.Citation25

In situ injectable drug delivery systems have also received much attention. Firstly, such methods are less invasive and less painful compared with implant insertion, which requires local anesthesia and surgery. Secondly, localized or systemic drug delivery can be achieved for prolonged periods of time, typically ranging from one to several months.Citation27 For instance, polyethylene glycol-oligo-glycolyl-acrylate can be cross-linked to encapsulate drugs using a photoinitiator such as eosin. However, such methods are restricted to the correct wavelength and the accessibility to a light source. More importantly, the potential toxicity of the photo cross-linker is another source of concern.

Therefore, compared with conventional drug delivery systems, RNTs as described here can self-assemble in situ and are water soluble, biocompatible nanomaterials, suitable for hydrophobic drug incorporation. Moreover, in the present study, TBL were introduced as a new generation of self-assembled RNTs because they have six twin G^C base units, which leads to stronger hydrogen bond networks, stronger π-stacking interactions, and as a result a more stable RNT. Although this study demonstrated the ability of RNTs to load TAM in water, we envision that several other hydrophobic drugs could be excellent candidates for encapsulation and delivery by the RNTs.

Conclusions

In summary, the relatively simple procedure described in this study to load TAM into RNTs could offer an ideal drug delivery system for hydrophobic drugs. The biocompatibility, amphiphilic nature of the RNTs solve a number of drug delivery problems, including limited water solubility and bioavailability in physiological environments. RNT-encapsulated TAM should be further studied as an anticancer coating on current implants or as stand-alone injectable drug delivery vehicle. Additional in vitro studies to study drug-release kinetics and the bioactivity of TAM after incorporation in RNTs are currently underway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brown University International Scholar Program, the Hermann Foundation, the National Research Council of Canada, the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the University of Alberta for funding this work. We also thank Dr Jae-Young Cho for recording the AFM images.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GuoWHuangKTangRXuHSynthesis, characterization of novel injectable drug carriers and the antitumor efficacy in mice bearing sarcoma-180 tumorJ Control Release200510751352216157412

- GuoWShiZLiangKChenXLiWPolyanhydride modified unsaturated polyesters as injectable drug carriers: Synthesis and antitumor efficacy in sarcoma-180 mice bearing tumorPolym Degrad Stabil20069129242930

- GuoWShiZLiangKLiuYChenXLiWNew unsaturated polyesters as injectable drug carriersPolym Degrad Stabil200792407413

- KakinokiSTaguchiTSaitoHTanakaJInjectable in situ forming drug delivery system for cancer chemotherapy using a novel tissue adhesive: Characterization and in vitro evaluationEur J Pharm Biopharm20076638339017240124

- OkinoHNakayamaYTanakaMIn situ hydrogelation of photocurable gelatin and drug releaseJ Biomed Mater Res20025923324511745558

- ReddyHLVivekKBakshiNTamoxifen citrate loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN™): Preparation, characterization, in vitro drug release, and pharmacokinetic evaluationPharm Dev Technol20061116717716749527

- JonesMCLerouxJCPolymeric micelles – a new generation of colloidal drug carriersEur J Pharm Biopharm19994810111110469928

- SharifiSMirzadehHImaniMInjectable in situ forming drug delivery system based on poly(e-caprolactone fumarate) for tamoxifen citrate delivery: Gelation characteristics, in vitro drug release and anti- cancer evaluationBiomaterials2009519661978

- KwonGSOkanoTPolymeric micelles as new drug the block copolymer, since the auxiliary agents are carriersAdv Drug Deliv Rev199621107116

- KataokaKHaradaANagasakiYBlock copolymer micelles for drug delivery: Design, characterization and biological significanceAdv Drug Deliv Rev20014711313111251249

- TorchilinVPStructure and design of polymeric surfactant-based drug delivery systemsJ Control Release20017313717211516494

- XuCXieJHoDAu-Fe3O4 dumbbell nanoparticles as dual-functional probesAngew Chem Int Ed Engl20084717317617992677

- LiuHWChenCHTsaiCLLinIHHsiueGHHeterobifunctional poly(ethylene glycol)-tethered bone morphogenetic protein-2- stimulated bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell differentiation and osteogenesisTissue Eng2007131113112417355208

- YangLWebsterTJNanotechnology controlled drug delivery for treating bone diseasesExpert Opin Drug Deliv2009685186419637973

- GindyMEPrud’hommeRKMultifunctional nanoparticles for imaging, delivery and targeting in cancer therapyExpert Opin Drug Deliv2009686587819637974

- ChunALMoralezJGFenniriHHelical rosette nanotubes: A more effective orthopaedic implant materialNanotechnology200415S234239

- ChunALMoralezJGWebsterTJHelical rosette nanotubes: A biomimetic coating for orthopedicsBiomaterials2005267304730916023193

- FenniriHMathivananPVidaleKLHelical rosette nanotubes: Design, self-assembly and characterizationJ Am Chem Soc20011233854385511457132

- MoralezJGRaezJYamazakiTHelical rosette nanotubes with tunable stability and hierarchyJ Am Chem Soc20051278307830915941263

- ZhangLRakotondradanyFMylesAJArginine-glycine-aspartic acid modified rosette nanotube-hydrogel composites for bone tissue engineeringBiomaterials2009301309132019073342

- ZhangLChenYRodriguezJBiomimetic helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium for improving orthopedic implantsInt J Nanomedicine2008332333318990941

- MacgregorJJordanVCBasic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen actionPharmacol Rev1998501511969647865

- OkadaHToguchiHBiodegradable microspheres in drug deliveryCrit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst1995121998521523

- FungLKSaltzmanWMPolymeric implants for cancer chemotherapyAdv Drug Deliv Rev19972620923010837544

- BitzCDoelkerEInfluence of the preparation method on residual solvents in biodegradable microspheresInt J Pharm1996131171181

- LiSLepageMMerandYBelangerALabrieFGrowth inhibition of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced rat mammary tumors by controlled-release low-dose medroxyprogesterone acetateBreast Cancer Res Treat1992241271378443400

- PackhaeuserCBSchniedersJOsterCGKisselTIn situ forming parenteral drug delivery systems: An overviewEur J Pharm Biopharm20045844545515296966

- AthanasiouKANiederauerGGAgrawalCMSterilization, toxicity, biocompatibility and clinical applications of polylactic acid/polyglycolicacid copolymersBiomaterials199617931028624401