Abstract

Boron nitride (BN) nanomaterials have been increasingly explored for potential biological applications. However, their toxicity remains poorly understood. Using Caenorhabditis elegans as a whole-animal model for toxicity analysis of two representative types of BN nanomaterials – BN nanospheres (BNNSs) and highly water-soluble BN nanomaterial (named BN-800-2) – we found that BNNSs overall toxicity was less than soluble BN-800-2 with irregular shapes. The concentration thresholds for BNNSs and BN-800-2 were 100 µg·mL−1 and 10 µg·mL−1, respectively. Above this concentration, both delayed growth, decreased life span, reduced progeny, retarded locomotion behavior, and changed the expression of phenotype-related genes to various extents. BNNSs and BN-800-2 increased oxidative stress levels in C. elegans by promoting reactive oxygen species production. Our results further showed that oxidative stress response and MAPK signaling-related genes, such as GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, MEK1, and PMK1, might be key factors for reactive oxygen species production and toxic responses to BNNSs and BN-800-2 exposure. Together, our results suggest that when concentrations are lower than 10 µg·mL−1, BNNSs are more biocompatible than BN-800-2 and are potentially biocompatible material.

Introduction

An increasing number of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) have been explored for diverse biomedical applications.Citation1 Among these ENMs, boron nitride (BN) NMs (also known as “white graphene”)Citation2 with a structure analogous to carbon NMs have been studied for drug delivery, tissue regeneration, and fluorescent-cell imaging.Citation3–Citation5 Hydrophobic BN nanospheres (BNNSs) and highly water-soluble BN powder (BN-800-2) with irregular shapes are two representative forms of BN NMs. BNNSs can be utilized to deliver cytosine–phosphate–guanine oligonucleotides and peptides into lysosomes after cellular uptake;Citation6–Citation8 similarly, BN-800-2 with high surface area and loading capacity also possesses the potential of being a drug-delivery vehicle.Citation9 Despite their potential value in biomedicine, BN NMs’ biocompatibility, a key feature fundamentally important for their biomedical application, is poorly understood, with conflicting evidence in the literature.Citation3,Citation10,Citation11 For instance, some studies claim that BN nanotubes (NTs) and hexagonal BN are more cytocompatible than their carbon counterparts in vitro and in vivo,Citation3,Citation4,Citation12,Citation13 whereas other studies report otherwise,Citation10 suggesting that further exploration on BN NM cytotoxicity is needed.

Caenorhabditis elegans is a self-reproducing free-living nematode species.Citation14 As a sensitive and cost-efficient whole-animal model with a short life cycle, C. elegans complements mammalian modelsCitation15–Citation18 for assessing the toxicity of NMs at the organism or population level.Citation19–Citation21 These NMs include metal nanoparticles (NPs; TiO2, Al2O3, and ZnO2)Citation22–Citation24 and carbon NPs (carbon NTs [CNTs], graphene oxide [GO], and graphite nanoplatelets).Citation25–Citation28

Here, we analyze the two aforementioned representative forms of BN NMs in C. elegans: BNNSs and BN-800-2. In this study, we examined the multiple phenotypic toxicities of two types of BN NMs with different morphology, size, and solubility using C. elegans in aqueous media. The toxic effects and dosage thresholds were assessed and determined by the exposure of worms to BNNSs or BN-800-2. The life span (lifetime), growth (length of worms), progeny (reproductive number), oxide-stress level, and material distribution were quantitatively analyzed as phenotypic indicators in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed worms. The relevant C. elegans mutants were employed to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the in vivo toxicity of BNNSs and BN-800-2.

Materials and methods

Preparation and characterization of BN-based nanomaterials

BNNSs and highly water-soluble BN-800-2 NM were kindly provided by Professor Tang (School of Materials Science and Engineering, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, China). In brief, BNNSs were synthesized by chemical deposition to an average diameter of approximately 150 nm per particle, detected by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, H-700FA, 75 kV; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) as previously reported.Citation29 BN-800-2 was synthesized by a thermal substitution reaction of carbon atoms in graphitic carbon nitrides in accordance with a previous method.Citation9 BNNSs and BN-800-2 at a concentration of 1,000 µg·mL−1 were stocked stably in K medium (distilled, deionized water with 10 mM NaOAc, 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM KCl, pH 5.5), a liquid medium for maintaining C. elegans, at 4°C. The working solution (1–500 µg·mL−1) was prepared by diluting the stock solution with K medium at room temperature. The pH value was then readjusted to 5.5. Dynamic light scattering and ζ-potential of BN materials at a concentration of 10 µg·mL−1 in water or K medium were measured with a Nano Zetasizer system (ZEN 3600; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) at room temperature (). The stock solution of 1,000 µg·mL−1 was dispersed in Milli-Q water after sonication for 30 minutes and stored at 4°C. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, US).

Table 1 Characterizations of BN nanomaterials (mean ± SD)

Worm culture

C. elegans wild-type N2, transgenic strains of oxIs12 [UNC47ⵆGFP; LIN15(+)], jcIs1 [AJM1ⵆGFP], and mutant stains of GAS1 (fc21), MEK1 (ks54), PMK1 (km25), SOD2 (ok1030), and SOD3 (gk235) were purchased from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN, US). They were maintained on nematode growth-medium agar plates and fed with Escherichia coli strain OP50 at 20°C as per a standard protocol.Citation14 For the age-synchronized test, gravid C. elegans were eluted and lysed by a standard hypochlorite procedure.Citation30 L1-stage or L4-stage larvae from an age-synchronized culture were exposed in 24-well sterile tissue plates shaken at 20°C, which were covered with aluminum foil to diminish the potential influence of light. Each well contained 500 µL aliquot of test solution based on K medium (pH 5.5)Citation31 for all the assays with shaking.

Larval growth, reproduction, and life-span assays

For the following tests, age-synchronized worms were transferred into 24-well sterile tissue plates with sufficient E. coli OP50 in K medium as previously described. BNNSs and BN-800-2 were prepared at final concentrations of 0, 1, 10, 100, and 500 µg·mL−1. For larval growth assays, body size at the flat surface area along the anterior–posterior axis of C. elegans from L1 larvae was shot every 24 hours for 3 successive days. Then, the C. elegans specimens were observed by bright-field microscopy (BX53 equipped with an XM10 digital microscope camera and CellSens Entry imaging software; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and measured with ImageJ Express software. At least ten replicates were employed for each assay in three independent tests. For progeny assays, one single synchronized L4-stage larva was placed into an individual well of 24-well sterile tissue plates.Citation32 The parent C. elegans specimens were transferred into a new well every 1.5 days. All embryos and larvae were counted after the transfer under stereo-zoom microscopy (SZX7; Olympus), and ten replicates were employed for each assay. To determine the lifespan of C. elegans exposed to BNNSs or BN-800-2, 30 L4-stage larvae were transferred into a fresh well, with treatments conducted every day during the brood period. The viability of each nematode was verified under stereo-zoom microscopy. Worms without pharyngeal bulb pumping or responding to a gentle blow with a micropipette were scored as dead.

Locomotion-behavior assays

Locomotion behaviors of worms were appraised by head-thrash and body-bend tests, performed as previously described.Citation33,Citation34 C. elegans exposed to BNNSs or BN-800-2 at different concentrations were drawn out and washed with K medium. Each worm was transferred into 60 µL K medium on the surface of agar in a sterile tissue plate and observed under stereo-zoom microscopy. A thrash was defined as a direction change of swing worms at the mid-body. The head thrashes were scored for 1 minute after a recovery period of 1 minute. For body-bend counting, animals were packed onto an empty agar plate and body bends counted for 20 seconds. A body bend was defined as a change in the direction of the posterior bulb of the pharynx along the body axis, assuming that the worm was crawling perpendicularly to the body axis. Fifteen animals were detected per treatment in three independent tests.

Visualization of γ-aminobutyric acid motor neurons

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) motor neurons were analyzed using an oxIs12 transgene strain expressing GFP-fused UNC47 protein. L4-stage larvae were exposed to 500 µg·mL−1 BNNSs or BN-800-2 in K medium on a shaker for 24 hours. Relative green fluorescence was examined with fluorescence microscopy (IX71 equipped with a DP73 digital microscope camera and CellSens Entry imaging software; Olympus) at 488 nm excitation wavelength and 510 nm emission filter. The average integrated optical density of green fluorescence (integrated optical density divided by area) was semiquantified with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software. Thirty C. elegans specimens for each group were counted.

Reactive oxygen species-production assays

After exposure of BNNSs or BN-800-2 at final concentrations of 0, 1, 10, 100, and 500 µg·mL−1 in K medium on a shaker for 24 hours, the examined L4-stage larvae were washed three times and incubated with 500 µL M9 buffer (3 g KH2PO4, 6 g Na2HPO4, 5 g NaCl, 1 mL 1 M MgSO4, H2O to 1 L) containing 100 µg·mL−1 of 2′,7′-dichlorodi hydrofluorescein diacetate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 hours at 20°C away from light. Tested C. elegans specimens were taken out and washed three times with M9 buffer and then examined under fluorescence microscopy at 488 nm excitation wavelength and 510 nm emission filter. The average integrated optical density of green fluorescence (integrated optical density divided by area) was semiquantified with Image-Pro. Fifty C. elegans specimens for each group were counted.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

For quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis, approximately 500 C. elegans specimens were exposed to 500 µg·mL−1 of BNNSs or BN-800-2 for 24 hours. Total RNA (~1 µg) of worms was extracted using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) with oligo-dT primer (Takara Bio). The qRT-PCR was carried out using a StepOnePlus RT-PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, US) and operated at optimized annealing temperature of 56°C for 40 cycles. The design of primers was based on the C. elegans database (www.wormbase.org) and blasted in the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The cycle of threshold (Ct) value of each sample was normalized by subtracting the mean Ct value of actin, as internal reference, and calculated into the relative-quantification fold change compared with the control group by an improved mathematical model.Citation35 Three independent replicates with three technical replicates were managed for all the tests.

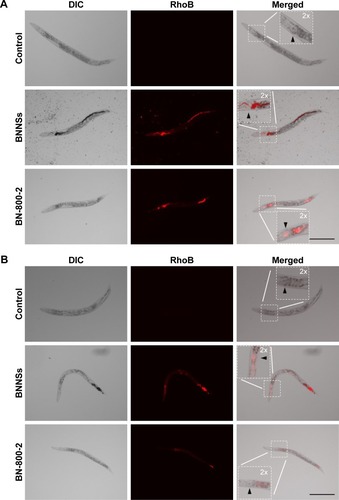

Biodistribution of BNNSs and BN-800-2 in C. elegans

To investigate the distribution of BNNSs and BN-800-2 in C. elegans by fluorescence microscopy, rhodamine B (RhoB) was loaded by blending it (1 mg) with BNNSs (10 mg each) or BN-800-2 (10 mg each) in 5 mL Milli-Q water over 24 hours at 20°C away from light. Uncombined RhoB was eliminated by dialysis against Milli-Q water through a dialysis membrane (molecular weight cutoff =1,000) over 72 hours. The BNNSs/RhoB and BN-800-2/RhoB produced were lyophilized and reserved at 4°C. For the test of distribution, C. elegans were cultured in 500 µL K medium with BNNSs/RhoB or BN-800-2/RhoB at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1 from L4-stage larvae for 24 hours away from light. For defecation assays, C. elegans were treated with RhoB-labeled BNNSs/RhoB or BN-800-2/RhoB for 24 hours at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1, then transferred and washed with pure K medium. Complete defecation was defined as no RhoB-labeled BN materials observed in the whole intestinal lumen of worms, the amount of which was recorded at 0, 15, and 30 minutes and 1, 3, 5, and 7 hours after washing. The examined C. elegans were observed using fluorescence microscopy at 550 nm excitation wavelength and 575 nm emission filter.

Statistical analysis

To analyze differences among all the groups, data acquired from growth assays, reproduction assays, locomotion-behavior assays, reactive oxygen species (ROS) assays, qRT-PCR, and distribution assays were evaluated with Student’s t-test for unpaired data. Data from life-span assays were calculated by Kaplan–Meier test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, US). Probability levels (P-values) of 0.05 or 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of BNNSs and BN-800-2

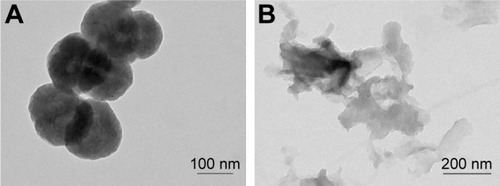

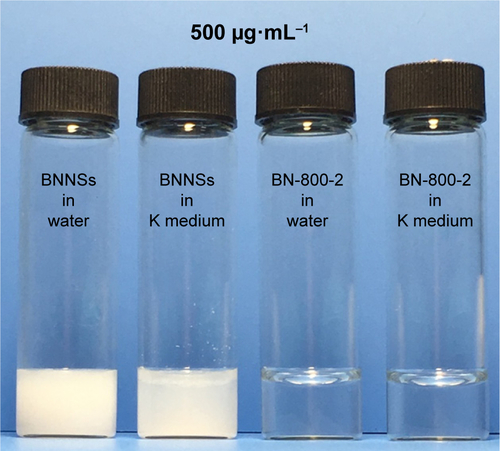

TEM imaging revealed that a single BNNS was 150 nm in diameter (). Because BN-800-2 showed polymorphic lamellar structure (), we measured the maximum diameter of aggregations less than 700 nm, in agreement with previous reports.Citation9,Citation29 Figure S1 shows that BN-800-2 displayed better solubility than BNNS suspensions in deionized water or K medium at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1 after sonication for 10 minutes. The hydrodynamic size of BNNSs was nearly twice as large as BN-800-2 in deionized water or K medium after sonication (). It is possible that lower average surface charge and fewer hydrophilic surface groups (eg, –OH) make BNNSs easier to aggregate than BN-800-2 in solution.Citation9,Citation29

Effects of life span of BNNSs or BN-800-2 on C. elegans life span

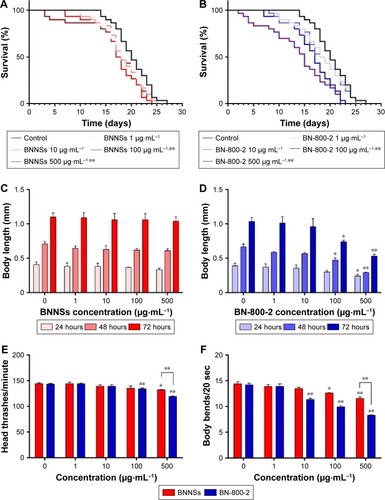

To investigate the effect of BN NMs on the life span of C. elegans, the animals were cultured with different concentrations of BNNSs or BN-800-2 from L4 larval developmental stage. Compared to the untreated control, the average life span was significantly reduced by approximately 3 days in the 100 µg·mL−1 and 500 µg·mL−1 BNNS-exposed group and 3 and 6 days in the 100 µg·mL−1 and 500 µg·mL−1 BN-800-2-exposed group, respectively (). These observations indicate that BN-800-2 shortened animal life span more significantly than BNNSs, likely due to its higher solubility.

Figure 2 Biological adverse effects of BNNSs and BN-800-2 on life span, growth, locomotion behavior, progeny, and expression of related genes in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Notes: Adverse effect on the life span of age-synchronized L4-stage larvae exposed to different concentrations of BNNSs (A) or BN-800-2 (B), cultured consecutively (n=30). The length of C. elegans on exposure to different concentrations of BNNSs (C) or BN-800-2 (D) was measured every 24 hours from L1-stage larvae to adults for 3 days consecutively (n=10, three repeats). Effects of exposure to BNNSs or BN-800-2 on head thrashes (E) and body bends (F) of L4-stage larvae after exposure for 24 hours (n=15, three repeats). (G) Number of progeny per worm exposed successively to different concentrations of BNNSs or BN-800-2 in L4-stage larvae (n=10). (H) Relative expression of growth- and longevity-related genes in L4-stage larvae with exposure to BNNSs or BN-800-2 at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1 for 24 hours (n=3). Three experimental repeats (three technical replicates for each experiment); C, control. All genes were normalized to ACT1 mRNA level and expressed as fold change relative to the untreated control. Worms were maintained in K medium in 24-well plates at 20°C in an incubator. Data presented as means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; SEM, standard error of mean.

Effects of BNNSs or BN-800-2 on growth, locomotion behavior, and reproduction of C. elegans

To evaluate the developmental toxicity of BN NMs, the body size of C. elegans was first measured. BNNS exposure at all the concentrations tested did not affect body extension during the L1 larval stage through adulthood (72 hours) (), whereas BN-800-2 exposure significantly reduced body length at concentrations over 100 µg·mL−1 (). These observations indicate that BN-800-2 but not BNNSs impaired the growth of worms.

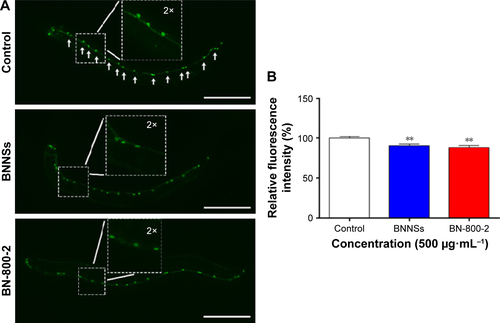

To investigate the behavioral influence of BN NMs, toxic tests for locomotion were performed on L4 larval C. elegans exposed to BN NMs for 24 hours. Both BNNS and BN-800-2 exposure (500 µg·mL−1) resulted in a mild reduction in head-thrash behavior, with BN-800-2 causing slightly more severe defects (). Similarly, BN-800-2 significantly affected more body bending (19.87%, 30.05%, and 34.12% for 10, 100, and 500 µg·mL−1, respectively) than BNNSs (6.62%, 12.46%, and 22.62% for 10, 100, and 500 µg·mL−1, respectively; ). Since locomotion is thought to be a sensitive indicator reflecting motor-neuron damage during ENM exposure,Citation20,Citation36,Citation37 we detected GFP-labeled UNC47 gene (a transmembrane vesicular GABA transporter) to evaluate the function of D-type GABAergic motor neurons, which innervate the dorsal and ventral body muscles (Figure S2).Citation38 The decreased expression of UNC47 in BNNS or BN-800-2 (90.77% and 88.39%, respectively) exposure suggests slight neurotoxicity induced by BN materials (Figure S2), consistent with the observed modest locomotion impairment ().

To examine the influence on reproductive organs, the number of progeny per worm was counted daily until egg-laying stopped, which was often on day 11 postembryonically. Both BNNSs and BN-800-2 significantly decreased the number of progeny at concentrations of 100 µg·mL−1 and 500 µg·mL−1. Of note, exposure to 500 µg·mL−1 BN-800-2 reduced reproductivity to approximately a third that of BNNSs (). These results collectively indicate that the highly water-soluble BN-800-2 is more toxic than hydrophobic BNNSs in growth, locomotion behavior, and reproduction.

Expression of growth- and longevity-related genes in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed C. elegans

To investigate further the molecular basis of BN-material toxicity, six growth-related genes (MTL1, MTL2, GSA1, LAG1, SEL8, and EFN2) and six lifespan-related genes (DAF2, DAF16, BAR1, HMP2, ETS4, and AKT1) were examined in exposed worms (Table S1). BNNS exposure significantly increased the expression of two growth-related genes: MTL1 (encoding metallothioneins) and GSA1 (encoding the mammalian orthologue of heterotrimeric G protein) (). In contrast, BN-800-2 exposure increased the expression of two growth-related genes – GSA1 and LAG1 (encoding the orthologue of the CBF1–RBP-JK–SuH–LAG1 family) – and four lifespan-related genes: DAF2 (encoding the orthologue of insulin/IGF receptor), DAF16 (encoding the orthologue of FoxO), BAR1, and HMP2 (encoding the orthologue of β-catenin) (). These data indicated that compared to BNNSs, BN-800-2 affected the expression of a wider spectrum of genes, consistent with BN-800-2’s higher toxicity to growth and life span.

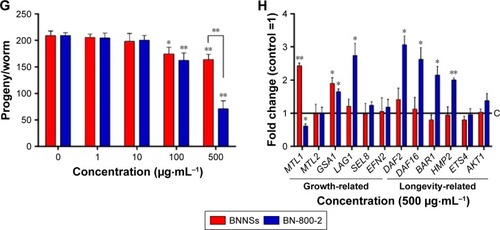

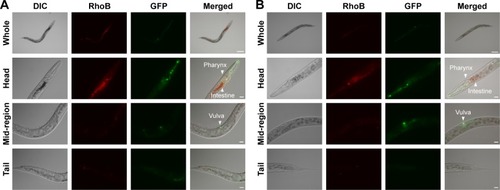

Exposure to BNNSs and BN-800-2 causes oxidative stress in C. elegans

ROS-induced oxidative stress is thought partly to account for ENM toxicity.Citation39 To assess oxidative stress caused by BN materials, we measured ROS levels in worms after treatment with BN materials for 24 hours (). While BNNSs increased ROS-fluorescence intensity at concentrations higher than 100 µg·mL−1, BN-800-2 promoted ROS generation at a lower concentration, 10 µg·mL−1, and effectively produced more ROS than BNNSs (2.7-fold for 100 µg·mL−1 and 3.4-fold for 500 µg·mL−1) (). Given that ROS production indicates the toxicity of nanobiomaterials, eg, GO,Citation28 CNTs,Citation26 TiO2, and ZnO,Citation36,Citation40 our data here suggest that ROS overproduction in the intestine tissue might be one of the mechanisms underlying adverse BNNS and BN-800-2 effects.

Figure 3 Alterations in ROS production and related-gene mRNA levels in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed Caenorhabditis elegans.

Notes: (A) Representative fluorescent micrography showed intestinal ROS production in worms exposed to BNNSs or BN-800-2 at different concentrations for 24 hours. (B) Quantification of average integrated optical density of ROS production in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed C. elegans (n=50). (C) Relative expression of genes related to oxidative stress response, including MAPK-signaling pathway, in C. elegans with exposure to BNNSs or BN-800-2 at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1. Three experimental repeats (three technical replicates for each experiment); C, control. All the respective mRNA levels were normalized to ACT1 mRNA levels and expressed as fold change relative to the untreated control. All experiments were done by exposing L4-stage larvae to BNNSs or BN-800-2 into K medium in 24-well plates for 24 hours at 20°C. Data presented as means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. Scale bar 200 µm.

Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; SEM, standard error of mean.

Exposure to BNNSs and BN-800-2 affects the expression of oxidative stress-related genes

Several antioxidant genes, such as superoxide dismutases, catalases, and glutathione-S-transferase, regulate ROS-triggered damage by catalyzing the ROS-scavenging progress.Citation41 To examine the role of ROS in the toxicity of BNNSs and BN-800-2, 16 genes related to oxidative-stress response were investigated in exposed C. elegans (Table S1). Compared to the control group, the mRNA levels of 14 stress-response genes involved in oxygen metabolism were altered in C. elegans exposed to 500 µg·mL−1 of BN-800-2. These genes were HSP16.1, HSP4, HSP70, ISP1, SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, CTL2, GAS1, GCS1, GST4, CLK1, PMK1, and MEK1 (). In contrast, the exposure of BNNSs changed the expression of fewer genes to a lesser extent (). These results indicate that BN-800-2 more prevalently affected the expression of ROS-related genes than BNNSs, suggesting BN-800-2 might induce more severe oxidative damage. Similarly, other ENM exposure also led to changed expression levels in oxidation-related genes, such as upregulation of SOD2, SOD3, ISP1, GAS1, and CLK1 for CNT exposure,Citation42 upregulation of SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, ISP1, and CLK1 for GO exposure,Citation28 and upregulation of HSP16.1, HSP70, SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, and CTL2 for ZnO NP exposure.Citation40

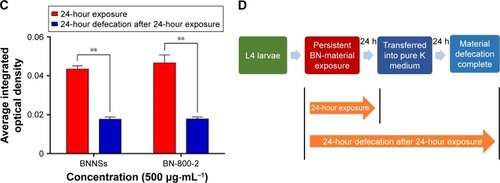

Biodistribution of BNNSs and BN-800-2 in C. elegans

Previous research revealed that the translocation level of ENMs from the primarily targeted organs in C. elegans (such as the epithelial cells of the intestine) to the secondarily targeted organs (such as alimentary and reproductive organs) was positively correlated with ENM toxicity.Citation20,Citation43 To test whether this was also the case for BN materials, BNNSs and BN-800-2 were visualized by RhoB labeling in treated worms. After exposure for 24 hours, most BNNSs or BN-800-2 were distributed within the primarily targeted organs (pharynx and digestive tract), with a small amount translocated to the head regions outside the pharynx (). Approximately half of BNNSs/RhoB and BN-800-2/RhoB were retained in the body after 24-hour defecation () and totally defecated from the intestinal lumen within 7 hours (Figure S3), suggesting that the worms did not have biological preferences on the translocation, accumulation, or excretion of BNNSs and BN-800-2. To locate more precisely the distribution sites of BNNSs and BN-800-2, we used a transgenic strain of AJM1 – jcIs1. This strain expresses GFP-fused AJM1 protein, an apical junction molecule of cells localized in intestine, pharynx, and vulva.Citation44 BNNSs and BN-800-2 remained mainly in primarily targeted organs, but not in secondarily targeted organs, such as the gonad and embryos, suggesting that the observed secondarily targeted organ-related functional defects caused by BN material exposure, including locomotion-behavior defects and progeny reduction, might have been induced by indirect effects, possibly ROS production ().

Figure 4 In vivo accumulation of BNNSs or BN-800-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Notes: (A) Representative fluorescent micrography of control (untreated) and L4-stage larvae after being treated with RhoB-labeled BNNSs or BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1) for 24 hours. Arrowheads indicate the pharynx. Inset images are enlargements of regions outlined by small boxes. (B) After being treated as in A, worms were transferred and cultured in pure K medium for defecation for 24 hours. (C) Quantification of average integrated optical density of RhoB in worms with persistent 24-hour exposure or worm-defecated materials for 24 hours after being treated as in A (n=50). (D) In vivo accumulation-assay procedure for exposure and defecation of BN materials. Worms were maintained in K medium in 24-well plates at 20°C in an incubator. Data presented as means ± SEM. **P<0.01. Scale bar 200 µm.

Abbreviations: BN, boron nitride; BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; DIC, differential interference contrast; RhoB, rhodamine B; SEM, standard error of mean.

Figure 5 In vivo distribution of BNNSs and BN-800-2 in transgenic strain of AJM1.

Notes: Representative fluorescent micrography of L4-stage larvae treated with (A) RhoB-labeled BNNSs (500 µg·mL−1) or (B) BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1) in K medium for 24 hours (n=50). GFP labels mouth, pharynx, vulva, and part of intestine. Scale bars 100 µm and 20 µm, respectively.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; DIC, differential interference contrast; RhoB, rhodamine B.

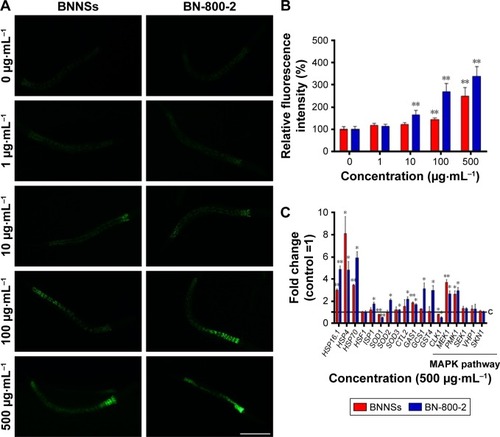

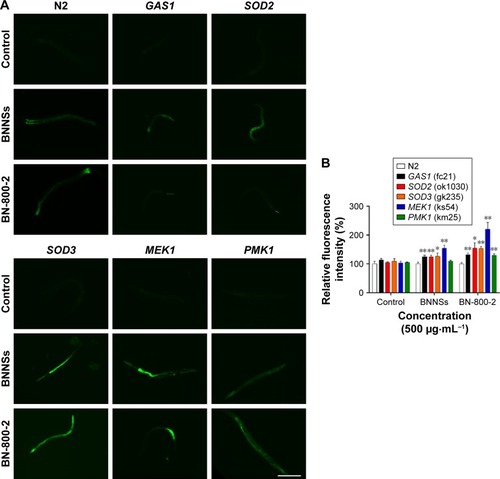

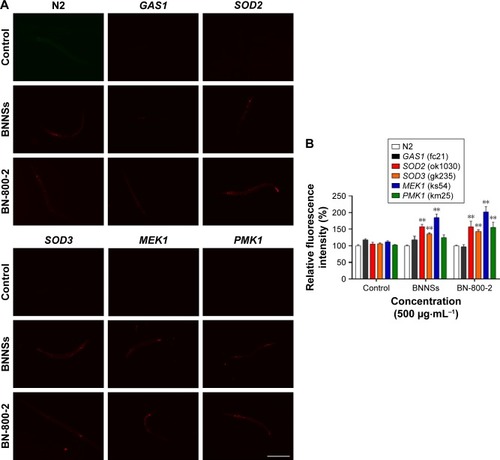

ROS production and BN accumulation in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed wild-type and mutant strains

Oxidative stress-related genes play important roles in ROS-induced toxicity for some ENMs, such as GO, TiO2 NPs and Al2O3 NPs.Citation24,Citation36,Citation37 To determine whether these genes were also involved in the toxicity induced by BN materials, we assessed the ROS production in wild-type and five mutant strains of oxygen-metabolism genes (GAS1, SOD2, and SOD3) and MAPK-signaling genes (MEK1 and PMK1) required for oxidative stress responses in L4 larvae exposed to BNNSs or BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1). Previous studies have demonstrated that defects in GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, MEK1, and PMK1 can increase ROS levels and enhance oxidative cellular damage.Citation45–Citation47 Our results showed that exposure to either BNNSs or BN-800-2 elevated ROS production in GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, and MEK1 mutants, suggesting the suppressive functional roles of GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, and MEK1 genes in ROS production (). Interestingly, the PMK1 mutant produced more ROS than the wild type only when exposed to BN-800-2. Considering that PMK1 enhances the activities of SOD and catalase,Citation48 these data suggest the MAPK-signaling pathway may be needed for eliminating ROS production induced specifically by BN-800-2.

Figure 6 ROS production in BNNS- and BN-800-2-exposed wild-type and mutant worms.

Notes: (A) Representative fluorescent micrography show intestinal ROS production in the wild-type and five mutants treated with BNNSs or BN-800-2 at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1. (B) Quantification of average integrated optical density of ROS visualized by ROS probe in the mutants indicated in A (n=50). The wild-type and five mutant worms at L4-stage larvae were treated with indicated BN materials in K medium for 24 hours. Data presented as means ± SEM, *P<0.05; **P<0.01. Scale bar 200 µm.

Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; SEM, standard error of mean.

We next determined whether the accumulation of BNNSs and BN-800-2 was influenced by ROS. The accumulation of BNNSs or BN-800-2 was significantly increased in SOD2, SOD3, and MEK1 mutants than in the wild type, suggesting that Mn-SODs and the MAPK-signaling pathway inhibit the accumulation of BNNSs and BN-800-2 (), consistent with the role of these genes in regulating the accumulation of other ENMs.Citation37,Citation42 Given the known functional role of SOD2 and SOD3 in scavenging ROS, SOD2 and SOD3 inhibition of BN accumulation was likely due to reduced ROS production, suggesting that ROS might be involved in promoting BN-material in vivo accumulation.

Figure 7 BN-material accumulation in wild-type and mutant worms.

Notes: (A) Representative fluorescent micrography of indicated mutants treated with RhoB-labeled BNNSs and BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1). The control was untreated. (B) Quantification of average integrated optical density of RhoB in worms from A (n=50). Wild-type and five mutant worms at L4 larval stage were treated with indicated BN materials in K medium for 24 hours. Data presented as means ± SEM. **P<0.01. Scale bar 200 µm.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; RhoB, rhodamine B; SEM, standard error of mean.

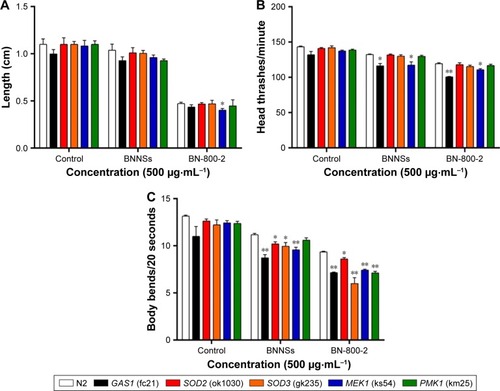

Effects of BNNSs and BN-800-2 on growth and locomotion behavior in wild types and mutants

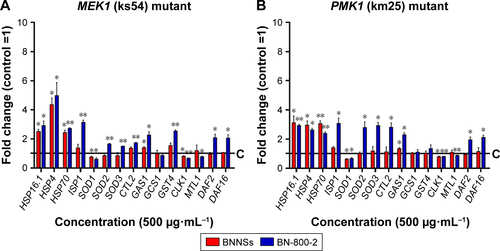

MEK1 encodes a homologue of mammalian MKK7 and promotes growth and movement in the presence of heavy metals and starvation.Citation49 In MEK1 mutants, a 72-hour exposure to BN-800-2 significantly shortened body length in comparison to the wild type (), suggesting that the increased ROS production caused by BN-800-2 exposure likely accounted for retarded growth. Further, the locomotion defects in head thrashes and body bends were also observed in MEK1 and GAS1, SOD2, and SOD3 mutants, whose corresponding genes are all involved in oxidative stress regulation (). Given that locomotion is a sensitive indicator reflecting neuronal damage during ENM exposure, these results suggest that these genes may suppress neuronal damage, possibly through their effects in reducing ROS. We next investigated the effects of MEK1 or PMK1 mutation for mRNA transcription of stress-response genes in BNNS and BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1)-exposed worms. Figure S4 shows mutant MEK1 or PMK1 inhibited the upregulation of MTL1 with exposure to BNNSs. Mutant MEK1 inhibited the upregulation of GCS1, and mutant PMK1 inhibited both GCS1 and GST4 with exposure to BNNSs and BN-800-2, respectively (Figure S4).

Figure 8 Growth and locomotion defects in BN-exposed mutants.

Notes: (A) Length of wild-type and mutant larvae consecutively exposed to 500 µg·mL−1 of BNNSs or BN-800-2 from L1-stage larvae was measured every 24 hours for 3 days (n=10, three repeats). Effects of exposure to BNNSs or BN-800-2 on head thrashes (B) and body bends (C) in wild-type and mutant L4-stage larvae after exposure for 24 hours (n=15, three repeats). Worms were maintained in K medium in 24-well plates at 20°C. Data presented as means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; SEM, standard error of mean.

Discussion

The toxicity of ENMs is thought to be positively correlated with their solubility.Citation50,Citation51 For instance, the toxic threshold for soluble GO is lower than hydrophobic graphene in C. elegans (10 µg·mL−1 vs >50 µg·mL−1).Citation21,Citation28 Moreover, for metal NPs in C. elegans, the toxic threshold of highly soluble Al2O3 NPs and ZnO NPs is lower than bulk Al2O3 (8.1 µg·mL−1 vs 23.1 µg·mL−1)Citation24 and ZnO (0.45 µg·mL−1 vs 2.25 µg·mL−1).Citation40 Similarly, our data demonstrate that the threshold for the highly water-soluble BN-800-2 to cause locomotion defects and ROS production was significantly lower than that for BNNSs (10 µg·mL−1 vs 100 µg·mL−1). Importantly, compared to carbon or metal NPs, the toxicity of BNNSs and BN-800-2 was lower in C. elegans, suggesting relatively good biocompatibility.

Although the accumulated amount of BN-800-2 and BNNSs within primary-target organs was similar, our results showed that soluble BN-800-2 induced more ROS production than BNNSs, suggesting that BN-800-2 is more toxic than BNNSs. Consistently, BN-800-2 exposure promoted more ROS production than BNNS exposure in most of the loss-of-function mutants of the key antioxidative genes. Given that ROS can impair biological barrier integrity, such as the intestinal epithelium, the observation that increased ROS production was correlated with enhanced BN-material in vivo accumulation might suggest a positive feedback between ROS production and the amount of BN retained in primarily targeted organs. Oxidative stress induced by ROS underlies the toxicity of ENMs, including behavior dysfunction and development.Citation40,Citation42 Supporting this notion, BN-800-2 exposure that produced more ROS than BNNS exposure consistently resulted in more severe defects in locomotion behavior (head thrashes/body bending) and postembryonic growth (body length) in the antioxidative mutants. Such locomotion defects are thought to be due to ROS neurotoxicity.Citation24 Our data showed that mitochondrial complex I, Mn-SOD, and MAPK signaling (GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, and MEK1 genes) were responsible for reducing BN material-induced ROS generation, which possibly in turn suppressed neurotoxicity.

Interestingly, while GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, and MEK1 were four shared genes associated with the toxicity of both BNNSs and BN-800-2, PMK1 appeared to be specifically required to suppress the multiple aspects of BN-800-2 toxicity. This observation indicates the involvement of PMK1 in antioxidative responses to BN-800-2 exposure, reflecting that BNNSs and BN-800-2 are capable of activating different antioxidative pathways, which might also contribute to the differences in toxicity observed between BNNSs and BN-800-2. Our results also implied that PMK1 might regulate BN-800-2 toxicity and accumulation through the transcriptional expression of GCS1 and GST4 (Figure S4) which are required for the synthesis of anti-ROS production of the polypeptide glutathione in C. elegans.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive data from an in vivo whole-animal model indicate that BNNS biocompatibility was higher than BN-800-2. High-dose exposure of BN-800-2 (over 10 µg·mL−1) caused multiple functional defects in C. elegans. The oxidative damage induced by ROS played an important role in the toxicity of BNNSs and BN-800-2, and was regulated by oxidative-stress response and MAPK-signaling-related genes, such as GAS1, SOD2, SOD3, MEK1, and PMK1.

Acknowledgments

NW and HW contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Programs (81272559, 81402875, and 81572866), the International Science and Technology Corporation Program of the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (S2014ZR0340), and the Science and Technology Program of the Chinese Ministry of Education (113044A), the Frontier Exploration Program of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (2015TS153), the Natural Science Foundation Program of Hubei Province (2015CFA049), and the Hubei Province Hundreds of Talents Program.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 BNNSs and BN-800-2 suspensions/solutions in water or K medium at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1.

Notes: BNNSs or BN-800-2 were suspended or dissolved into water or K medium, and the mixture was sonicated for 10 minutes.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride.

Figure S2 The GABA nervous system in untreated control and BNNS- and BN-800-2-exposed worms.

Notes: (A) BNNSs or BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1) were used to treat L4-stage larvae whose GABA motor neurons expressed a GFP construct (oxIs12) driven by a GABA motor neuron-specific promoter (n=30). The worms were cultured in K medium without food for 24 hours during the treatment. Arrows indicate the position of D-type neurons in the control. Inset images are enlargements of regions outlined by small boxes. (B) Quantification of fluorescence intensity in worms treated as described in A. Data presented as means ± SEM. **P<0.01. Scale bar 100 µm.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; SEM, standard error of mean.

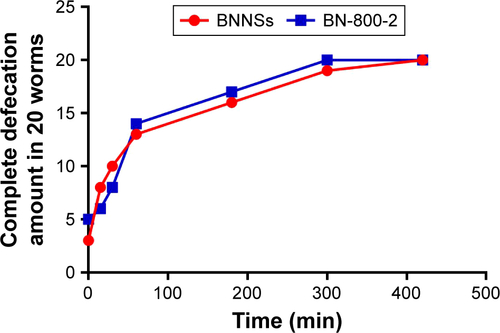

Figure S3 Defecation kinetics of worms after BN exposure.

Notes: Worms were subjected to 24-hour exposure to RhoB-labeled BNNSs and BN-800-2 (500 µg·mL−1) in K medium (n=20). After exposure, the worms were washed and transferred to a clean plate for defecation in the absence of food. Complete defecation was defined as no RhoB-labeled BN materials observed in whole intestinal lumen of worms, the amount of which was recorded at 0, 15, and 30 minutes and 1, 3, 5, and 7 hours from transference. Data presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; RhoB, rhodamine B.

Figure S4 mRNA expression of oxidative stress-response genes in BNNS- or BN-800-2-exposed MEK1 and PMK1 mutant Caenorhabditis elegans.

Notes: The relative expression of genes related to oxidative stress response in MEK1 (A) and PMK1 (B) mutant C. elegans with exposure to BNNSs or BN-800-2 at a concentration of 500 µg·mL−1 for 24 hours. Three experimental repeats (three technical replicates for each experiment); C, control. All mRNA levels were normalized to ACT1 mRNA levels and expressed as fold change relative to the untreated control. All experiments were done by exposing L4-stage larvae to BNNSs or BN-800-2 in K medium in 24-well plates at 20°C. Data presented as means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: BNNSs, boron nitride nanospheres; BN-800-2, highly water-soluble boron nitride; SEM, standard error of mean.

Table S1 Information on genes related to stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans

References

- CondeJDiasJTGrazúVMorosMBaptistaPVde la FuenteJMRevisiting 30 years of biofunctionalization and surface chemistry of inorganic nanoparticles for nanomedicineFront Chem201424825077142

- SongLCiLLuHLarge scale growth and characterization of atomic hexagonal boron nitride layersNano Lett20101083209321520698639

- ChenXWuPRousseasMBoron nitride nanotubes are non-cytotoxic and can be functionalized for interaction with proteins and cellsJ Am Chem Soc2009131389089119119844

- PengJWangSZhangPHJiangLPShiJJZhuJJFabrication of graphene quantum dots and hexagonal boron nitride nanocomposites for fluorescent cell imagingJ Biomed Nanotechnol20139101679168524015497

- ParraCMontero-SilvaFHenriquezRSuppressing bacterial interaction with copper surfaces through graphene and hexagonal-boron nitride coatingsACS Appl Mater Interfaces20157126430643725774864

- ZhiCMengWYamazakiTBN nanospheres as CpG ODN carriers for activation of Toll-like receptor 9J Mater Chem2011211452195222

- ZhangHYamazakiTZhiCHanagataNIdentification of a boron nitride nanosphere-binding peptide for the intracellular delivery of CpG oligodeoxynucleotidesNanoscale20124206343635022941279

- ZhangHChenSZhiCYamazakiTHanagataNChitosan-coated boron nitride nanospheres enhance delivery of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and induction of cytokinesInt J Nanomedicine201381783179323674892

- WengQWangBWangXHighly water-soluble, porous, and biocompatible boron nitrides for anticancer drug deliveryACS Nano2014866123613024797563

- HorváthLMagrezAGolbergDIn vitro investigation of the cellular toxicity of boron nitride nanotubesACS Nano2011553800381021495683

- WengQHWangXBWangXBandoYGolbergDFunctionalized hexagonal boron nitride nanomaterials: emerging properties and applicationsChem Soc Rev201645143989401227173728

- LiuBQiWTianLIn vivo biodistribution and toxicity of highly soluble peg-coated boron nitride in miceNanoscale Res Lett201510147826659609

- SalvettiARossiLIacopettiPIn vivo biocompatibility of boron nitride nanotubes: effects on stem cell biology and tissue regeneration in planariansNanomedicine (Lond)201510121911192225835434

- BrennerSThe genetics of Caenorhabditis elegansGenetics197477171944366476

- KalettaTHengartnerMOFinding function in novel targets: C. elegans as a model organismNat Rev Drug Discov20065538739816672925

- BoydWAMcBrideSJFreedmanJHEffects of genetic mutations and chemical exposures on Caenorhabditis elegans feeding: evaluation of a novel, high-throughput screening assayPLoS One2007212e125918060055

- LeungMCWilliamsPLBenedettoACaenorhabditis elegans: an emerging model in biomedical and environmental toxicologyToxicol Sci2008106152818566021

- GiacomottoJSégalatLHigh-throughput screening and small animal models, where are we?Br J Pharmacol2010160220421620423335

- NelAXiaTMengHNanomaterial toxicity testing in the 21st century: use of a predictive toxicological approach and high-throughput screeningAcc Chem Res201346360762122676423

- ZhaoYWuQLiaYWangDTranslocation, transfer, and in vivo safety evaluation of engineered nanomaterials in the non-mammalian alternative toxicity assay model of nematode Caenorhabditis elegansRSC Adv201331757415757

- JungSKQuXAleman-MezaBMulti-endpoint, high-throughput study of nanomaterial toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegansEnviron Sci Technol20154942477248525611253

- KharePSonaneMPandeyRAliSGuptaKCSatishAAdverse effects of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles in soil nematode, Caenorhabditis elegansJ Biomed Nanotechnol20117111611721485831

- LiYWangWWuQMolecular control of TiO2-NPs toxicity formation at predicted environmental relevant concentrations by Mn-SODs proteinsPLoS One201279e4468822973466

- LiYYuSWuQTangMPuYWangDChronic Al2O3-nanoparticle exposure causes neurotoxic effects on locomotion behaviors by inducing severe ROS production and disruption of ROS defense mechanisms in nematode Caenorhabditis elegansJ Hazard Mater2012219–220221230

- ZanniEDe BellisGBraccialeMPGraphite nanoplatelets and Caenorhabditis elegans: insights from an in vivo modelNano Lett20121262740274422612766

- ChenPHHsiaoKMChouCCMolecular characterization of toxicity mechanism of single-walled carbon nanotubesBiomaterials201334225661566923623425

- NouaraAWuQLiYCarboxylic acid functionalization prevents the translocation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes at predicted environmentally relevant concentrations into targeted organs of nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanoscale20135136088609623722228

- WuQYinLLiXTangMZhangTWangDContributions of altered permeability of intestinal barrier and defecation behavior to toxicity formation from graphene oxide in nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanoscale20135209934994323986404

- TangCBandoYHuangYZhiCGolbergDSynthetic routes and formation mechanisms of spherical boron nitride nanoparticlesAdv Funct Mater2008182236533661

- DonkinSGWilliamsPLInfluence of developmental stage, salts and food presence on various end points using Caenorhabditis elegans for aquatic toxicity testingEnviron Toxicol Chem1995141221392147

- WilliamsPLDusenberyDBAquatic toxicity testing using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegansEnviron Toxicol Chem199091012851290

- MiddendorfPJDusenberyDBFluoroacetic acid is a potent and specific inhibitor of reproduction in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegansJ Nematol199325457357719279811

- TsalikELHobertOFunctional mapping of neurons that control locomotory behavior in Caenorhabditis elegansJ Neurobiol200356217819712838583

- WangDShenLWangYThe phenotypic and behavioral defects can be transferred from zinc-exposed nematodes to their progenyEnviron Toxicol Pharmacol200724322323021783815

- PfafflMWA new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCRNucleic Acids Res2001299e4511328886

- WuQZhaoYLiYWangDSusceptible genes regulate the adverse effects of TiO2-NPs at predicted environmental relevant concentrations on nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanomedicine201410612631271

- WuQZhaoYLiYWangDMolecular signals regulating translocation and toxicity of graphene oxide in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanoscale2014619112041121225124895

- McIntireSLReimerRJSchuskeKEdwardsRHJorgensenEMIdentification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporterNature199738966538708769349821

- NelAXiaTMädlerLLiNToxic potential of materials at the nanolevelScience2006311576162262716456071

- KharePSonaneMNagarYSize dependent toxicity of zinc oxide nanoparticles in soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanotoxicology20159442343225051332

- BlokhinaOVirolainenEFagerstedtKVAntioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a reviewAnn Bot200391217919412509339

- WuQLiYLiYCrucial role of the biological barrier at the primary targeted organs in controlling the translocation and toxicity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegansNanoscale2013522111661117824084889

- PluskotaAHorzowskiEBossingerOvon MikeczAIn Caenorhabditis elegans nanoparticle-bio-interactions become transparent: silica-nanoparticles induce reproductive senescencePLoS One200948e662219672302

- KöppenMSimskeJSSimsPACooperative regulation of AJM-1 controls junctional integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans epitheliaNat Cell Biol200131198399111715019

- KayserEBMorganPGSedenskyMMMitochondrial complex I function affects halothane sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegansAnesthesiology2004101236537215277919

- Neumann-HaefelinEQiWFinkbeinerEWalzGBaumeisterRHertweckMSHC-1/p52Shc targets the insulin/IGF-1 and JNK signaling pathways to modulate life span and stress response in C. elegansGenes Dev200822192721273518832074

- SuthammarakWSomerlotBHOpheimESedenskyMMorganPGNovel interactions between mitochondrial superoxide dismutases and the electron transport chainAging Cell20131261132114023895727

- ZarseKSchmeisserSGrothMImpaired insulin/IGF1 signaling extends life span by promoting mitochondrial L-proline catabolism to induce a transient ROS signalCell Metab201215445146522482728

- KogaMZwaalRGuanKLAveryLOhshimaYA Caenorhabditis elegans MAP kinase kinase, MEK-1, is involved in stress responsesEMBO J200019195148515611013217

- SunJWangFSuiYEffect of particle size on solubility, dissolution rate, and oral bioavailability: evaluation using coenzyme Q10 as naked nanocrystalsInt J Nanomedicine201275733574423166438

- KatsumitiAArosteguiIOronMGillilandDValsami-JonesECajaravilleMPCytotoxicity of Au, ZnO and SiO2 NPs using in vitro assays with mussel hemocytes and gill cells: relevance of size, shape and additivesNanotoxicology201610218519325962683