?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

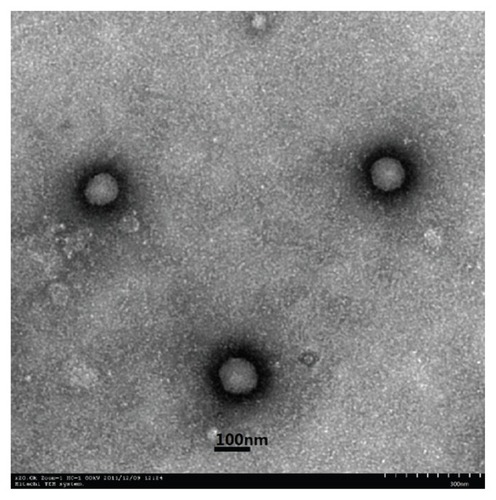

The aim of this study was to design and characterize solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) modified with stearic acid–octaarginine (SA-R8) as carriers for oral administration of insulin (SA-R 8-Ins-SLNs). The SLNs were prepared by spontaneous emulsion solvent diffusion methods. The mean particle size, zeta potential, drug loading, and encapsulation efficiency of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs were 162 nm, 29.87 mV, 3.19%, and 76.54%, respectively. The zeta potential of the SLNs changed dramatically, from −32.13 mV to 29.87 mV, by binding the positively charged SA-R8. Morphological studies of SA-R8-Ins-SLNs using transmission electron microscopy showed that they were spherical. In vitro, a degradation experiment by enzymes showed that SLNs and SA-R8 could partially protect insulin from proteolysis. Compared to the insulin solution, the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs increased the Caco-2 cell’s internalization by up to 18.44 times. In the in vivo studies, a significant hypoglycemic effect in diabetic rats over controls was obtained, with a SA-R8-Ins-SLN pharmacological availability value of 13.86 ± 0.79. These results demonstrate that SA-R8-modified SLNs promote the oral absorption of insulin.

Introduction

Oral delivery of insulin as a noninvasive therapy for diabetes mellitus is still a challenge to drug-delivery technology, as it cannot be administered currently via the oral route, due to rapid enzymatic degradation in the stomach, inactivation and digestion by enzymes in the intestinal lumen, and poor permeability across the intestinal epithelium, due to its high molecular weight and lack of lipophilicity.Citation1 However, oral insulin is advantageous because it is delivered to the liver, its primary site of action, via portal circulation, a mechanism very similar to endogenous insulin.Citation2

Different formulation approaches have been investigated to overcome the gastrointestinal tract barriers for the delivery of insulin via the oral route, such as the use of liposomes, microemulsion, microspheres, and nanoparticles.Citation3 Among the possible strategies for oral delivery of insulin, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) represent a promising approach.Citation4 The advantages of SLNs include improved efficacy, reduced toxicity, protection of active compounds, and enhanced biocompatibility. SLNs have a large specific surface area of physiological compatible lipid matrix, and their protection power against the gastrointestinal environment is mostly dependent on the degree of protein encapsulation within these nanostructures.Citation5,Citation6 Furthermore, the carrier itself can be taken up, to a certain extent, by epithelial cells or the lymphoid tissues in Peyer’s patches.Citation7

Cell-penetrating peptides have attracted increasing attention in recent years as a promising vehicle for facilitating the cellular uptake of various molecular cargos.Citation8 Among them, arginine-rich derivatives of the HIV Tat are the most widely studied peptides.Citation9–Citation11 It is well know that homopeptides consisting of 7–9 arginines display higher cellular uptake compared to the Tat peptide itself.Citation12 Kamei et al proved that cell-penetrating peptides could improve the intestinal absorption of insulin.Citation13 Furthermore, the addition of fatty acid to polyarginines dramatically improves their cellular uptake.Citation14–Citation16

Therefore, in the present study, insulin SLNs modified with stearic acid–octaarginine (SA-R8-Ins-SLNs) were prepared in order to improve the stability and bioavailability of orally administered insulin. The spontaneous emulsion solvent diffusion method was adopted, and the formed SLNs were then characterized and evaluated by dynamic light scattering, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), internalization effect in Caco-2 cells, and hypoglycemic experiment in diabetic rats.

Materials and methods

Materials

Insulin (27.5 IU/mg) was purchased from Xuzhou Wanbang Biochemical Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Xuzhou, China). Stearic acid–octaarginine (SA-R8) was purchased from Shanghai Gil Chemical Co, Ltd (Shanghai, China). Soybean phospholipid was obtained from Shanghai Taiwei Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Shanghai, China). Monostearin, poloxamer 188, and polysorbate 80 were purchased from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Co, Ltd (Shanghai, China). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol- 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Trypsin and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium were purchased from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). All other solvents were of analytical or chromatographic grades and commercially available.

Cell culture and animal models

The Caco-2 cells, a kind gift from Dr Moniqué Rousset of INSERM U178 (Villejuif, France), were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Sprague Dawley diabetic rats, weighing 200 ± 10 g, were obtained from the Animal Center of China Pharmaceutical University, and all the animal experiments were performed according to the Guiding Principles of the Care and Use of Experiment Animals at China Pharmaceutical University. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, China Pharmaceutical University, China.

The preparation of SLNs

The SLNs, loaded with insulin and SA-R8 (SA-R8-Ins- SLNs), were prepared using the spontaneous emulsion solvent diffusion method: 5 mg of insulin were dissolved in 2 mL 0.01 M hydrochloric acid (inner aqueous phase) and added to a 10 mL acetone solution containing 90 mg of stearic acid and 10 mg of soybean phospholipids (oily phase). The resulting mixtures were dispersed at 50 W for 15 seconds with an ultrasonic probe (JY92-II ultrasonic processor; Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co, Ltd, Ningbo, China) leading to W/O emulsions. Then, the emulsions were poured into 100 mL 1.6% poloxamer 188 and 15% SA-R8 solution under continuous stirring, using a DC-40 stirrer (Hangzhou Electrical Engineering Instruments, Hangzhou, China) at 500 rpm for 1 hour, in order to form SLNs. The untrapped drug and adjuvant were removed by filtration. The preformed SLNs were filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose nitrate filter membrane, and then lyophilized in the presence of 5% mannitol. The lyophilized powders were kept in a refrigerator at 4°C. SLNs containing insulin without SA-R8 (Ins-SLNs) were also prepared in the same manner to serve as controls. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

The characterization of SLNs

Determination of the encapsulation efficiency and drug loading of the insulin

Insulin entrapment efficiency (EE) and drug loading (DL) of the SLNs were determined by HPLC, as reported previously (see Equationequations (1)(1) and Equation(2)

(2) , respectively).Citation18

Determination of the DL and binding efficiency of SA-R8

The SA-R8-Ins-SLNs were dissolved in 50% ethanol under water bath at 70°C for 10 minutes, and then cooled to room temperature to preferentially precipitate the lipid. The SA-R8 content in the supernatant, after centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, L8-60M; Beckman, Fullerton, CA) in an ultimate filtration tube (molecular weight cutoff = 10,000), was measured by an HPLC method at 220 nm using an LC-10 Avp pump and an LC-10 Avp UV-VIS detector (both obtained from Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The chromatographic conditions employed were as follows: mixture of acetonitrile and water (51:49, v/v) as a mobile phase, Shim-pack CLC-ODS column at a temperature of 30°C (5 μm, 150 mm, 6 mm id), flow rate of 1.0 mL · min−1, and sample injection volume of 20 μL.

The calibration curve for the quantification of SA-R8 was linear over a range of standard concentrations of SA-R8, from 10 μg · mL−1 to 200 μg · mL−1, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.9997. The limit of detection was 10 μg · mL−1. The binding efficiency (BE) and DL of SA-R8 attached to the SLNs were calculated using Equationequations (3)(3) and Equation(4)

(4) , respectively:

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

The mean particle size and the zeta potential of the SA-R8- Ins-SLNs were determined with a Zetasizer (3000 HS; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). Its morphology was characterized by TEM (NanoScope V; Veeco/Digital Instruments, Plainview, NY), with a 5 μm scanner in contact mode.

Enzymatic stability studies with pepsin and trypsin

To assess the protective effect against gastrointestinal degradation, the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs were incubated with a simulated gastric fluid pH = 1.2 (with pepsin) and a simulated intestinal fluid pH = 6.8 (with trypsin) in a water bath oscillator at 37°C. At predetermined time intervals, samples were withdrawn and the enzymatic reaction stopped by 0.05 mol/L NaOH (pepsin) and 0.1 mol/L HCL (trypsin). The remaining amount of insulin was assayed with HPLC. All the experiments were performed in hexaplicate.

Transport experiments in the Caco-2 cell

Caco-2 cell monolayers were prepared by cultivating Caco-2 cells on polycarbonate membrane filters for 3 weeks. The Caco-2 cells were seeded on 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well, and then incubated for 24 hours. The culture medium was replaced by the uptake medium.Citation17 For the uptake studies, insulin samples were used in free form and in the form of SLNs. Then, 2.0 mL of 0.25 mg/mL final concentration of insulin, Ins-SLNs, and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs were added to the apical side of the cell culture dish. The cells were incubated at 37°C, and 200 μL samples were withdrawn from the basolateral part at the predetermined times of 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 minutes, and replaced with equal volumes of fresh HEPES-buffered Hank’s balanced salt solution. The samples were then analyzed for insulin content by the HPLC method. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) were calculated according to the following equation:

where Papp is the apparent permeability in cm/s, dQ/dt is the permeability rate, A is the diffusion area of the monolayer (cm2), and C0 is the initial concentration of the insulin. Statistical differences were calculated by using one-way analyses of variance at a significant level of P < 0.05.

Absorption enhancement ratio (R) was calculated as follows:

In vivo hypoglycemic effect

The lyophilized powder of Ins-SLNs with and without SA-R8 was dissolved in distilled water and administered to the duodenum of fasted diabetic rats, at an insulin dose of 25 IU/kg. Insulin powder delivered orally at 25 IU/kg and subcutaneous injection at 2 IU/kg served as controls. Each group contained six rats. Blood samples were collected from the tail vein before drug administration and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 hours after duodenal drug administration, and blood glucose levels were determined by using a glucose GOD-PAD kit (Shanghai Kexin Biochemical Reagent Industry, Shanghai, China).

PA% was calculated by using the following equations:

where AAC refers to the areas above the glucose reduction– time curve, which was calculated from time 0 hours to 12 hours by using the trapezoid method.Citation18

Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t-test, and the differences were judged to be significant at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

The preparation of SLNs

Preliminary studies were carried out to determine the relationship between the formulation parameters and the properties of the Ins-SLNs. Two major parameters affected the properties of the SLNs: the stearic acid:insulin weight ratio, which exerted a significant effect on the EE% of insulin; and the SA-R8 and soybean phospholipid concentration in the oily phase, which affected the size distribution of the Ins-SLNs. An increase in the relative amount of stearic acid to insulin resulted in an increase in the EE% of insulin and SA-R8. When the ratio reached 15:1, the highest EE% of insulin and SA-R8 was achieved, and an even higher ratio would no longer increase them. The appropriate percentage of soybean phospholipids was 5%~10%. Below 5% of the SLN matrix, the average diameter was larger than 200 nm; above 10% of the SLNs matrix, the polydispersity index of the nanoparticles increased. Furthermore, the appropriate percentage of SA-R8 in the formulation was limited to 10%~15% of the SLN matrix. At this percentage, the zeta potential value of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs was 30 mV, below 8% of the SLNs matrix; the zeta potential of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs was lower than 20 mV, and a higher SA-R8 amount (above 15%) did not increase its DL% or zeta potential in the SLNs, but inversely lowered its EE%. Other influential factors, such as the concentration of poloxamer 188, volume of inner aqueous phase, and volume of oily phase were investigated, and it was found that they contributed little to the properties of the SLNs. Thus, the optimal formulation of the Ins-SLNs was chosen as follows: 5 mg insulin, 15 mg SA-R8, 90 mg stearic acid, and 10 mg soybean phospholipids as the oily phase, and poloxamer 188 (1.6% solution) as the stable agent. For comparing with the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, the Ins-SLNs were prepared using the same method used for SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, but without SA-R8. The characterization results of SA-R8- Ins-SLNs and Ins-SLNs are listed in .

Table 1 DL, EE, average diameter, PDI, and zeta potential of Ins-SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs

The freeze-dried Ins-SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs appeared as a white powder, and they were easily dispersed in water to form translucent solutions with a visible, sky-blue opalescence. As revealed by TEM (), the SA-R8-Ins- SLNs exhibited a smooth, spherical morphology and were well dispersed and separated. Furthermore, the size of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs determined with TEM (about 120 nm) was smaller than that of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs in an aqueous phase (162.4 nm ± 15.23 nm), which might be caused by the collapse of the outer shell during the drying process in the TEM experiment.

Enzymatic stability studies with pepsin and trypsin

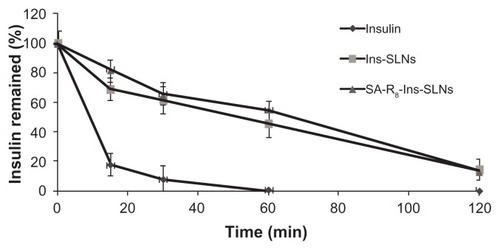

shows the percentage of remaining insulin after incubation of free insulin solution, Ins-SLNs, and SA-R8- Ins-SLNs in simulated gastric fluid (SGF) with pepsin. Insulin was degraded rapidly by SGF with pepsin within 1 hour. Compared to the free insulin solution, about 45.6% and 54.7% of insulin remained at 1 hour incubation of Ins- SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, respectively, with pepsin. This result proved that the SLNs had a certain effect in protecting insulin from degradation in SGF with pepsin. Moreover, the statistical analysis demonstrated that the protective effects of Ins-SLNs were not statistically different (P > 0.05) than those of SA-R8-Ins-SLNs at each time point, suggesting that the lipid matrix of the SLNs had an advantage in protecting insulin from enzymatic degradation. This result has been confirmed by several researchers.Citation6,Citation19

Figure 2 The remaining ratio of insulin after the incubation in SGF with pepsin.

Abbreviations: Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles; SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles modified with stearic acid–octaarginine; SGF, simulated gastric fluid.

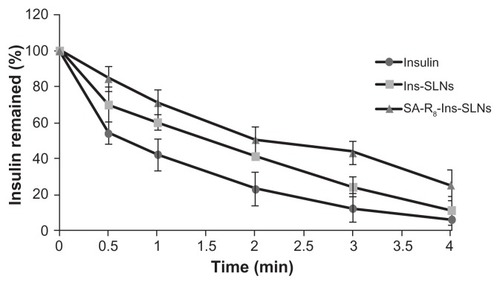

shows the percentage of remaining insulin after incubation with simulated intestinal fluid in the presence of trypsin, a common intestinal protease. The free insulin was degraded more slowly by trypsin than by pepsin, and only 6.4% of insulin remained at 4 hours. About 11.6% of insulin was recovered after 4 hours incubation of Ins-SLNs with trypsin, and about 25.7% of insulin remained in SA-R8-Ins- SLNs at 4 hours incubation with trypsin. This finding also suggested that the SLNs and SA-R8 had a synergistic effect in protecting insulin from the gastrointestinal enzymes.

Figure 3 Remaining ratio of insulin after incubation in SIF with trypsin.

Abbreviations: Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles; SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles modified with stearic acid–octaarginine; SIF, simulated intestinal fluid.

It has been reported that trypsin cleaves insulin at the B22-Arg residue, which is essential for its activity,Citation20 while pepsin rapidly cleaves the B24-/B25-Phe and B26-Tyr residuesCitation21 of insulin. Therefore, SA-R8 might protect insulin from degradation by the mechanism of competition with trypsin in simulated intestinal fluid, but it had no effect on the degradation activity of pepsin in SGF, due to the fact that R8 does not possess the same amino residues cleaved by pepsin.Citation22

Transport experiments in the Caco-2 cell

summarizes the Papp and R values obtained from transport across the Caco-2 monolayer in the presence of insulin, Ins-SLNs, and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs. Compared to the insulin solution, Ins-SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs promoted Caco-2 cell internalization by 2.25 and 18.44 times, respectively. This indicated that insulin entrapped in a SLN carrier could pass through the Caco-2 monolayer more efficiently than insulin on its own; moreover, the presence of SA-R8 significantly enhanced transportation efficiency. This result is in agreement with previous reportsCitation13,Citation20 that R8 increased the absorption of insulin.

Table 2 Apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) and absorption enhancement ratio (R) for insulin across Caco-2 cell monolayers

In vivo hypoglycemic effect

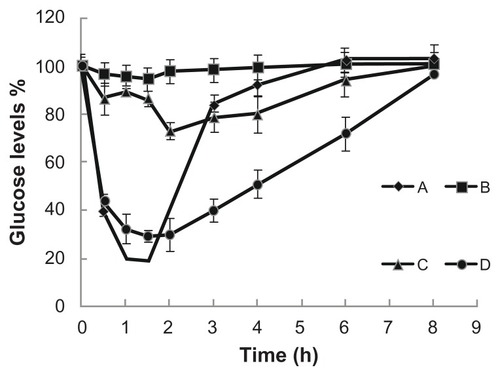

The glucose response profiles following the duodenal administration of the three samples to streptozocin-diabetic rats at a dose of 25 IU/kg are shown in . As expected, the insulin standard solution, as a control, showed no hypoglycemic effect. The Ins-SLN group had a certain hypoglycemic effect, with a maximum blood glucose lowering of 73.2% at 2 hours, while the SA-R8-Ins-SLN group achieved a significant hypoglycemic effect, with a maximum blood glucose lowering of 29.7% at 1.5 hours.

Figure 4 Blood glucose levels changes after subcutaneous or duodenal administration to STZ-diabetic rats. (A) subcutaneous administration of insulin (2 IU/kg); (B) insulin standard solution (25 IU/kg); (C) duodenum administration of Ins-SLNs (25 IU/kg); (D) SA-R8-Ins-SLNs (25 IU/kg).

Abbreviations: Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles; SA-R8-Ins-SLNs, insulin solid lipid nanoparticles modified with stearic acid–octaarginine; STZ, streptozocin.

This study was in agreement with previous findings that R8 is a useful tool for delivering macromolecules across cell membranes, as reported by various researchers.Citation20 lists the pharmacological availability (PA%) of the three samples administered to the duodenum of diabetic rats. PA% was calculated relative to the subcutaneous injection of 2 IU insulin/kg. The PA% obtained following duodenal administration of Ins-SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs at 25 IU insulin/kg was 4.28% and 13.86%, respectively.

Table 3 The relative pharmacological availability of both SLNs

As shown in , the PA% of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs was three times higher than that of Ins-SLNs, with a more apparent hypoglycemic effect (). In addition, SA-R8- Ins-SLNs promoted internalization of insulin in Caco-2 cells 8.19 times more than Ins-SLNs. This could have been caused by the partial degradation of SA-R8 and insulin in the harsh environment of the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, polymer coating of SA-R8-Ins-SLNs by chitosan, alginate, and hyaluronic acid might be a useful strategy. Further research is in progress in this area.

Conclusion

In this study, Ins-SLNs and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs were successfully prepared by the spontaneous emulsion solvent diffusion method. They were characterized by a spherical morphology, uniform size, positive zeta potentials, and high insulin entrapment efficiency. The typical cell penetration peptide SA-R8 was efficiently absorbed into the SLNS. Consequently, a dramatic change in zeta potential value between Ins-SLNs (−32 mV) and SA-R8-Ins-SLNs (30 mV) was observed, confirming the binding interactions occurring between SA-R8 with dense positive charges and the negatively charged insulin, soybean phospholipids, and stearic acid.

Insulin was partially protected from gastrointestinal enzymes by incorporation into SLNs and SA-R8. SA-R8- Ins-SLNs increased the uptake of the drug in the Caco-2 cell monolayer, which yielded a more potent hypoglycemic effect following duodenal administration. In conclusion, Ins-SLNs modified with a SA-R8 drug were able to increase the stability of insulin, improve the transportation efficiency in Caco-2 cells, and increase the in vivo hypoglycemic effect in diabetic rats. Thus, SA-R8 and SLNs could be a promising vehicle for oral delivery of insulin. However, further studies should focus more on the stability of insulin in the harsh gastrointestinal environment and the absorption mechanism of the SA-R8-Ins-SLNs.

Acknowledgments

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 30901867 and No 30973649) is gratefully acknowledged for financial support. This work was also supported by the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No 20090096110002) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (JKQ2011016).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Bernkop-SchnurchAKastCEGuggiDPermeation enhancing polymers in oral delivery of hydrophilic macromolecules: thiomer/GSH systemsJ Control Release20039329510314636716

- JoshiSRParikhRMDasAKInsulin – history, biochemistry, physiology and pharmacologyJ Assoc Physicians India200755Suppl192517927007

- XiongXYLiYPLiZLVesicles from Pluronic/poly(lactic acid) block copolymers as new carriers for oral insulin deliveryJ Control Release20071201–2111717509718

- MüllerRHKeckCMChallenges and solutions for the delivery of biotech drugs – a review of drug nanocrystal technology and lipid nanoparticlesJ Biotechnol20041131–315117015380654

- ElsayedARemawiMAQinnaNFaroukABadwanAFormulation and characterization of an oily-based system for oral delivery of insulinEur J Pharm Biopharm200973226927919508890

- MorishitaMPeppasNAIs the oral route possible for peptide and protein drug delivery?Drug Discov Today20061119–2090591016997140

- Garcia-FuentesMTorresDAlonsoMJDesign of lipid nanoparticles for the oral delivery of hydrophilic macromoleculesColloids Surf B Biointerfaces200227159168

- LeeJYBaeKHKimJSNamYSParkTJIntracellular delivery of paclitaxel using oil-free, shell cross-linked HSA – multi-armed PEG nanocapsulesBiomaterials201132338635864421864901

- BarnesMPShenWCDisulfide and thioether linked cytochrome c-oligoarginine conjugates in HeLa cellsInt J Pharm20093691–2798419059469

- WalrantACorreiaIJiaoCYDifferent membrane behaviour and cellular uptake of three basic arginine-rich peptidesBiochim Biophys Acta20111808138239320920465

- TakayamaKTadokoroAPujalsSNakaseIGiraltEFutakiSNovel system to achieve one-pot modification of cargo molecules with oligoarginine vectors for intracellular deliveryBioconjug Chem200920224925719161253

- WenderPAMitchellDJPattabiramanKPelkeyETSteinmanLRothbardJBThe design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transportersProc Natl Acad Sci U S A20009724130031300811087855

- KameiNMorishitaMEdaYIdaNNishioRTakayamaKUsefulness of cell-penetrating peptides to improve intestinal insulin absorptionJ Control Release20081321212518727945

- FutakiSOhashiWSuzukiTStearylated arginine-rich peptides: a new class of transfection systemsBioconjug Chem20011261005101111716693

- KatayamaSHiroseHTakayamaKNakaseIFutakiSAcylation of octaarginine: implication to the use of intracellular delivery vectorsJ Control Release20111491293520144669

- MaeMEl AndaloussiSLundinPA stearylated CPP for delivery of splice correcting oligonucleotides using a non-covalent co-incubation strategyJ Control Release2009134322122719105971

- MaoSGermershausOFischerDLinnTSchnepfRKisselTUptake and transport of PEG-graft-trimethyl-chitosan copolymerinsulin nanocomplexes by epithelial cellsPharm Res200522122058206816170693

- NakamuraKMurrayRJJosephJIPeppasNAMorishitaMLowmanAMOral insulin delivery using P(MAA-g-EG) hydrogels: effects of network morphology on insulin delivery characteristicsJ Control Release200495358959915023469

- ZhangLSongLZhangCRenYImproving intestinal insulin absorption efficiency through coadministration of cell-penetrating peptide and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrinCarbohyd Polym201287218221827

- SchillingRJMitraAKDegradation of insulin by trypsin and alpha- chymotrypsinPharm Res1991867217272062801

- RiemenMWPonLACarpenterFHPreparation of semisynthetic insulin analogues from bis(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-desoctapeptide-insulin phenylhydrazide: importance of the aromatic region B24–26Biochemistry1983226150715156340739

- FasanoAUzzauSModulation of intestinal tight junctions by zonula occludens toxin permits enteral administration of insulin and other macromolecules in an animal modelJ Clin Invest1997996115811649077522