Abstract

Purpose

Overall health status indicators have improved significantly over the past three decades in Indonesia. However, the country’s maternal mortality ratio remains high with a stark inequality by region. Fewer studies have explored access inequity in maternal health care service over time using multiple inequality markers. In this study, we analyzed Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data to explore trends and inequities in use of any antenatal care (ANC), four or more ANC (ANC4+), institutional birth, and cesarean section (c-section) birth in Indonesia during 1986–2012 to inform policy for future strategies ending preventable maternal deaths.

Methods

Indonesian DHS data from 1991, 1994, 1997, 2002/3, 2007, and 2012 surveys were downloaded, merged, and analyzed. Inequity was measured in terms of variation in use by asset quintile, parental education, urban–rural location, religion, and region. Trends in use inequities were assessed plotting changes in rich:poor ratio, rich:poor difference, and concentration indices over period based on asset quintiles. Sociodemographic determinants for service use were explored using multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Findings

Between 1986 and 2012, institutional birth rate increased from 22% to 73% and c-section rate from 2% to 16%. Private sector was increasingly contributing in maternal health. There were significant access inequities by asset quintile, parental education, area of residence, and geographical region. The richest women were 5.45 times (95% CI: 4.75–6.25) more likely to give birth in a health facility and 2.83 times (95% CI: 2.23–3.60) more likely to give birth by c-section than their poorest counterparts. Urban women were 3 times more likely to use institutional birth and 1.45 times more likely to give birth by c-section than rural women. Use of all services was higher in Java and Bali than in other regions. Access inequity was narrowing over time for use of ANC and institutional birth but not for c-section birth.

Conclusion

Ongoing pro-poor health-financing strategies should be strengthened with introduction of innovative ways to monitor access, equity, and quality of care in maternal health.

Introduction

Strategies for reduction of maternal mortality ratio (MMR) have undergone many changes since inception of the Safe Motherhood Initiative in 1987.Citation1 The current global recommendation is for all births to be guided by a skilled birth attendant supported by effective referral linkage with hospitals capable of performing blood transfusion and surgery.Citation2 Inequity has been identified as a key constraint in maternal health as existing data depict huge inequity between and within countries with regard to both access to care and levels of MMR.Citation3 Several innovative demand side health financing models have been initiated in different contexts.Citation4 However, their evaluations remain insufficient. In addition, monitoring of progress in Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) paid inadequate attention to equity.Citation5 The drive toward universal health coverage (UHC) is central to the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that prioritizes health equity with specific call to reduce inequality – referring to any quantifiable differences, variations, and disparities in different aspects of health across individuals or social groups,Citation6 as well as within and between countries.Citation7 Accordingly, a global framework has been developed to disaggregate SDG targets and indicators by sociodemographic strata in order to allow the assessment of equitable service distribution.Citation8

Indonesia is home to around 13,000 islands with hundreds of diverse ethnic groups,Citation9 grouped into 34 provinces, 98 municipalities, and 410 districts.Citation10 Some regions are more developed in terms of economy, education, and infrastructure.Citation9 The wealthiest, the urban, and those living in Java and Bali enjoy better availability and access to basic services including health.Citation11,Citation12 Health status indicators have improved, with life expectancy rising from 63 years in 1990 to 71 years in 2012, under-five mortality falling from 52 to 31 deaths per 1,000 live births and infant mortality falling from 41 to 26 deaths per 1,000 live-births between 2000 and 2012.Citation13 However, MMR remained high (210 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010), and a stark inequality persists across regions. For example, in Papua – the most Eastern part of Indonesia – the MMR was 573 per 100,000 live births in 2010, more than double of the national estimate during that period.Citation14 The high MMR with prevailing inequity fundamentally violates Indonesian women’s right to health.Citation15

The government is striving for the highest possible standard of health for all women in the country.Citation16 A number of evolving maternal health and health-financing strategies have been implemented. Important among them are the village midwife program,Citation17 the insurance program for maternal and child health,Citation18 and the placement and incentive programs in underserved areas.Citation11,Citation19,Citation20 A National Health Insurance Program (Jaminan Kesehatans Nasional[JKN]) have been launched in 2014 to facilitate achieving UHC.Citation21 Country data suggest some improvement in terms of service coverage, but not equity.Citation22 Fewer studies in Indonesia have explored access inequity in maternal health over time using multiple inequality markers. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) provide unique opportunity for tracking health inequities over time and between countries. In this paper, we analyzed six consecutive Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey (IDHS) data to explore trends and inequities in access to key maternal health care services between 1986 and 2012 to inform policy for future strategies ending preventable maternal deaths.

Methods

With permission from MEASURE DHS (www.measuredhs.com), we downloaded, merged, and analyzed the 1991, 1994, 1997, 2002/3, 2007, and 2012 Indonesian DHS datasets to explore trends, inequities, and determinants of maternal health care service utilization in Indonesia. This study was exempt from review by the ethics committee because the data used were publicly available and no respondent information was obtained. Before receiving access to the data, an electronic registration form highlighting the desired data and plan for analysis was submitted and approved by MEASURE DHS. All data were reported in aggregate, and no attempt was made to identify study participants.

The current study explored service utilization among women in Indonesia who gave their last birth in the 3 years prior to each survey year. The outcome measures focused on the utilization of any antenatal care (any ANC), four or more ANC (ANC4+), institutional birth, and birth by cesarean section (c-section). The inclusion of any ANC and ANC4+ was based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation that ANC is fundamental to ensure the delivery of effective and appropriate screening, prevention, and treatment of complication around pregnancy.Citation23 The recommendation suggests a minimum of four focused ANCs as a lower number of visits has been associated with increased likelihood of perinatal morbidity.Citation23 Inequities were measured in terms of inequality in access by different sociodemographic characteristics including asset quintiles, parental education (none, primary, secondary, or higher), clusters of regions (Sumatera, Java and Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, or Maluku and Papua), areas of residence (urban or rural), and religions (Islam or others). Influence of maternal age (categorized into five age groups), birth order (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6+), and year of birth upon use of maternal health care services was also explored.Citation11

Asset quintiles were computed survey year-wise following principal component and factor analysis methods using information on construction material of floor, wall, and roof; the source of drinking water; the type of latrine; electricity supply; and ownership of radio, telephone, motorcycle, television, car, and bicycle.Citation24 The trends and inequities were examined at 4-year time intervals (except for the year 2010–2012, which covered 3 years). Sociodemographic determinants were explored using multivariable logistic regression analysis, by quantifying both unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for each of the outcome variables using Wald tests to assess statistical significance (with 95% CIs and level of significance, 0.05), taking into account survey design (sampling weights and strata) and clustering effect.

To look into trends in inequities, we used relative measurement of rich:poor ratio; absolute measurement of rich:poor difference; and the concentration index (with 95% CIs). The concentration index is considered as a better measurement of inequality, which quantifies how specific goods and services are distributed among different socioeconomic groups. The value of the index varies between +1 and −1; positive values indicate a higher concentration of services among higher socioeconomic groups and vice versa. If there is no socioeconomic-related inequity, the concentration index would be zero.Citation25 Unadjusted and adjusted annual time trends for each of the outcome variables were also explored to determine whether the odds of use of maternal health care services were improving at the same rate in different socioeconomic groups. All statistical analyses were performed in Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).Citation26

Result

Trends in sociodemographic characteristics of women

In this study, we included 104,220 women in the final analysis who gave birth between 1986 and 2012. shows considerable changes in sociodemographic characteristics of women over the past 25 years. The percentage of women with no education decreased from 15.3% in 1986–1989 to 2.2% in 2010–2012, while the percentage of husbands with no education reduced from 9.8% to 1.4% during the same period. The percentage of urban population increased from 29.1% in 1986–1989 to 48.8% in 2010–2012. During the study period, the percentage of households from the lowest asset quintile group dropped from 21.46% to 15.05% and those from the highest asset quintile group grew from 14.77% to 21.9%. There was a significant demographic shift as well; the proportion of adolescent mothers increased from 2.26% to 5.22%; the primigravidae mothers increased from 15.8% to 37.6%; and women with 6 or more birth order reduced from 16.2% to 3.72% between 1986 and 2012 ().

Table 1 Trends in sociodemographic characteristics in Indonesia (1986–2012)

Trends in maternal health care service utilization

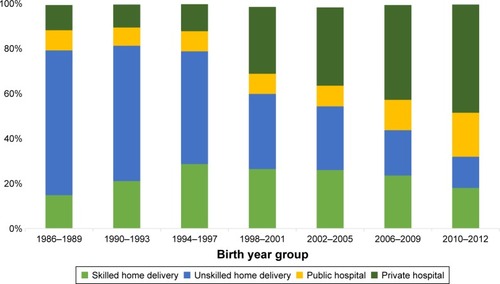

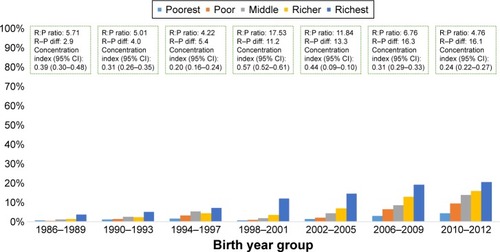

shows that between 1986 and 2012, the utilization of any ANC increased from 81% to 95%, the use of ANC4+ increased from 61% to 85%, institutional birth increased from 22% to 73%, and c-section birth increased from 2% to 16%. A sharp increase in institutional birth was observed after 1998. Population-based c-section rate increased steadily and just crossed the upper limit of global recommendation of 15% in 2012.

Figure 1 Trend in the use of any ANC, ANC4+, institutional delivery, and c-section (1986–2012).

presents the annual trends of use showing that during the study period, the utilization of any ANC services was actually decreasing at a rate of 5% per year, and the use of ANC4+ remained the same, while an increasing trend was observed for uptake of both institutional birth (5% per year) and c-section birth (4% per year). Annual trend for institutional birth was better among the poorer and rural women and in Nusa Tenggara region. For c-section birth, the trend was higher among wealthier households, in urban areas, and in Nusa Tenggara region. Annual trend for institutional birth was 7% among rural women and 3% among urban women. However, the annual trend for c-section favored the urban women (4%) than rural (3%) and the richest women (5%) than the poorest (3%).

Table 2 Annual trends in any ANC, ANC4+, institutional birth, and cesarean birth in Indonesia (1986–2012) stratified by asset quintile, area of residence, and place of residence

Place of birth

shows that institutional birth rate increased from 22% to 73% between 1986 and 2012; however, the increase was contributed mainly by the private sector facilities (). Institutional birth in private facilities increased from 11.2% to 48.1%, while in public sector facilities the increase was only ~10% from 9.1% to 19.6%. There was no increase in home birth by skilled birth attendants since 1998.

Sociodemographic determinants of maternal health care service utilization

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed statistically significant relationship between sociodemographic factors and use variables included in the analysis (). In the model where effects of covariates were controlled statistically, all sociodemographic variables evolved as significant predictors for use of any ANC, ANC4+, institutional birth, and birth by c-section. However, the strength and direction of associations varied. There was significant use inequity by asset quintile, education, area of residence, and region. A mother from the richest quintile household was 5.45 times (adjusted OR: 5.45; 95% CI: 4.75–6.25) more likely to give birth in a health facility than a mother from the poorest quintile household. Similarly, the richest quintile mothers were 2.83 times (adjusted OR: 2.83; 95% CI: 2.23–3.60) more likely to give birth by c-section than their poorest counterpart. Education of mothers evolved as the number one predictor for use of c-section birth and for institutional birth. A mother with higher education was 4.36 times (adjusted OR: 4.36; 95% CI: 3.46–5.50) more likely to give birth at health facility and 3.12 times (adjusted OR: 3.12; 95% CI: 1.89–5.15) more likely to give birth by c-section than her illiterate counterpart. Utilization also varied significantly by religion, area of residence, and region. Uses were higher among non-Muslims, in urban area and in Java and Bali Sumatera region. By geographic location and using Java and Bali as the reference, there was lower propensity of women from other regions to use maternal health care services. Women from Maluku and Papua used the services the least, and they were about 50% less likely to use any ANC (adjusted OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.36–0.55), ANC4+ (adjusted OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.47–0.59), and institutional birth (adjusted OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.39–0.52), and about 20% less likely to give birth by c-section (adjusted OR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.61–0.94) than women from Java and Bali. Older age and lower parity were positively correlated with service utilization ().

Table 3 Determinants of any ANC, ANC4+, institutional birth, and cesarean birth in Indonesia (1986–2012)

Trends in inequities in maternal health care service utilization

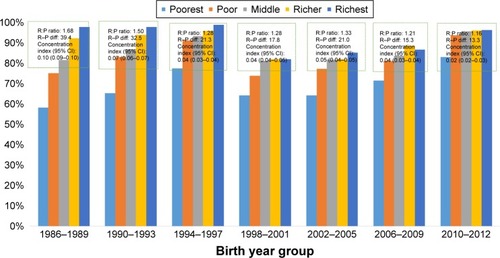

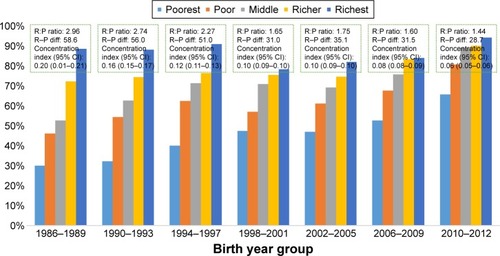

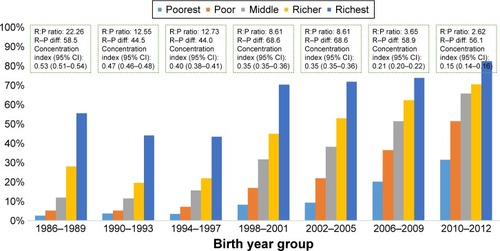

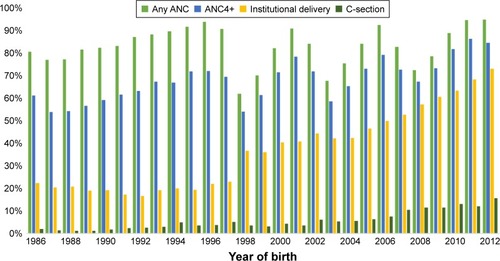

In –, we have plotted rich:poor ratio, rich–poor difference, and concentration indices based on asset quintiles to show changes in equity in maternal health care services utilization. Findings show signs of improvement in addressing access inequity in use of any ANC, ANC4+, and institutional births. For institutional birth, rich:poor ratio reduced from 20.3 to 2.6, while concentration index reduced from 0.53 to 0.15 between 1986–1989 and 2010–2012 (). However, no sign of equity gain was observed for c-section ().

Discussion

The current study revealed that Indonesia is experiencing a positive change in the social determinants of health over the past two to three decades. There has been a shift in demographic characteristics of women, from high to low parity and from older to younger age-group mothers. However, an increase in the proportion of adolescent mothers is worrying. Overall, utilization of maternal health care services has increased, reflecting improved coverage and access. There was variation in utilization across urban–rural and geographical regions. Women who lived in Java–Bali and in urban areas used maternal health care services more. Use inequity persisted for all use variables, and by all inequality measures. Nevertheless, access inequity in terms of asset quintile was reducing over time, and for all use variables except for c-section birth. Private sector was increasingly contributing in maternal health as caregivers. Further reduction in use inequity remains imperative to decrease maternal mortality and to achieve SDG target for maternal health.Citation27

Indonesia is a vast and diverse country geographically and culturally.Citation9 Some regions in Indonesia, especially Java–Bali, are more developed than the others in terms of economic activity, infrastructure, and population,Citation9 which has created differences in availability and access to basic services such as education and health.Citation11 Inequity between regions, rich– poor, and urban–rural characterize the health care situation in Indonesia.Citation28 The capital city Jakarta and several big cities in Java and Bali have higher density of health facilities and health workers.Citation28 Moreover, the richest and living in urban settings have bigger propensity to access health facilities than their poorest counterparts.Citation12 Nonetheless, economic growth has been attributed as the driving force behind the positive change in social determinants of health in Indonesia,Citation29,Citation30 resulting in education attainment gain, urbanization, and improved household possessions as observed in this study. These improvements are promising with the given established influence upon women’s status and health.Citation15,Citation31,Citation32 Maternal education evolved as number one predictor of use of institutional and c-section birth in our study. Literature suggests that female education improves health awareness leading to the ability of seeking appropriate care.Citation31–Citation33

Our study confirmed that substantial use inequity persists in maternal health in Indonesia; however, it varied between outcome indicators, it had been narrowed for use of any ANC, ANC4+, and institutional birth, but remained high for c-section birth. Our analysis depicts that although overall use of c-section was increasing, use inequity was deteriorating. This costly surgical procedure was increasingly favoring the richer, educated, and urban women, indicating that the most vulnerable groups of women who actually need these lifesaving services may still fail to access them. The c-section rate among women from the poorest quintile households for instance was less than global recommendations of minimum 5% during 2010–2012. Such inequity probably partially explains the failure of Indonesia in attaining MDG 5 goal in reducing MMR by three-quartersCitation34 and possibly had a negative impact on MDG 4 target as well as in reducing under-five mortality rate by two-thirds of the baseline in 1990.Citation35

Along with education and economic status, geographic location is of equal importance.Citation15,Citation36–Citation38 In this study, utilization was significantly lower in rural areas and outside of Java–Bali regions. Our results corroborate with finding from previous studies as similar disparities in terms of rural–urban and regional differential in health outcomes have been reported earlier.Citation33,Citation38,Citation39 Undeniably, health facilities, health workers, and other resources are more concentrated in urban areas and in Java–Bali,Citation11,Citation28 making the services more readily available in these locations. From the annual trend, it was obvious that worse-off regions such as Maluku and Papua consistently lagged behind. These provinces continue to experience health worker shortage, limited infrastructure, and high poverty rates.Citation39–Citation41 Government decentralization in 2001 has been criticized for persistent geographic inequity. Multiple challenges continued to hinder health sector improvement through decentralization, including complicated funding and disbursement, limited capacity, and lack of transparency and accountability of local government.Citation11,Citation37,Citation39

The government has implemented a number of health agendas. Community health centers in every subdistrict (Puskesmas) and village (Pustu) have been the cornerstone of Indonesian health system since the late 1960s.Citation37 Maternal health care service was integrated through monthly community health post (Posyandu) with the involvement of community volunteer to increase ANC coverage and raise awareness for skilled attendance.Citation28 To improve access to skilled attendance, birthing centers (Polindes) were established in every village.Citation28 The availability of health workers was ensured through compulsory government services introduced in 1974, in which doctor, midwives, and nurse were deployed to different parts of Indonesia.Citation42 Bidan di Desa (village midwife) was introduced in 1989, where existing nurses were given additional training on midwifery and deployed at a community level to conduct deliveries either in Polindes or at home.Citation28 Unfortunately, due to difficult and isolated geographic location, smaller incentive package, and lack of opportunity for professional development, these jobs were not attractive to this new cadre of service providers leading to unfilled position and/or absenteeism.Citation28,Citation43 This situation may also explain the slow decrease in MMR despite the reduction in the proportion of home delivery. Furthermore, a study by the World Bank suggested a weak correlation between the availability of midwives and maternal and neonatal health outcomes in Indonesia,Citation41 highlighting low quality of health care at the primary health care level. The condition is further impaired by a shortage of health facilities with proper equipment and supporting infrastructures, particularly in the Eastern part of Indonesia.Citation44 This increasing shortage of human resources, supplies, logistic, and medicine also aggravated the discrepancy between geographic locations.Citation43 Nevertheless, a full coverage of Puskesmas was achieved 20 years after its introductionCitation37 with a relatively better distribution of health workers achieved in the latter part of the 1980s.Citation43 The low service fee allowed the demand for health services to increase and the overall health outcomes to improve until 1997 when the Asian financial crisis started.Citation37

During the crisis, an increase in prices for health care affected government expenditure and reduced quality in public sector while increasing service fee.Citation45 At the same time, the households faced unemployment and decline in real wages and coped by cutting expenses including for health care.Citation45 Consequently, there was a remarkable decrease in public health servicesCitation37,Citation45 and widened use inequity across region.Citation37 To ensure access to health care for poor households, government started distributing health cards (Jaring Pengaman Sosial Bidang Kesehatan).Citation37 However, the health cards were not considered effective because of ignorance of the beneficiaries and corruption among service providers.Citation37

Deterioration of quality in public sector has also prompted preference to seek care in private sector, which is considered to have better perceived quality with only a slight difference in cost.Citation37 Our findings support previous results, showing a bigger increase in private sector utilization during and after the crisis. In Indonesia, private sector consists largely of individual providers, especially midwives. Since decentralization, national government was no longer absorbing health workers into the government system, rather prompting doctor and midwives to find employment in private sector or open private practices.Citation43 In addition, proliferation of private training institutions produced more graduates who could not find employment with government.Citation43 It promoted these graduates to work as individual private providers, making them an important source of health care in Indonesia including maternal health.Citation46 Unfortunately, government has minimal control of private sector with underdeveloped regulation and accreditation.Citation42 This could have further negatively affected the quality of care.Citation47,Citation48

To respond to the MMR stagnation, Indonesian government has introduced a number of initiatives on maternal and neonatal health. One notable program is the Flying Health Care introduced to serve remote and challenging areas in eight provinces in Sumatera, Kalimantan, Papua, and Maluku.Citation49 The program places a team of medical professionals for at least 3 months and rotates the team throughout the year. To increase the availability of medical professionals in remote areas, the government also started a mandatory placement for specialist doctors, including new graduates from obstetrics and pediatrics program.Citation50,Citation51 However, these program would need the support of good health infrastructure within the remote areas and indeed underline the issue of quality of care.Citation51

To improve the referral system and quality of care, several innovative programs were introduced in the Eastern parts of Indonesia. East Nusa Tenggara province, for example, implemented a monitoring and referral system using short messaging service (SMS) for every pregnant woman since 2011, called the 2H2 program.Citation52 The 2H2 program aimed to detect pregnant women who have high risk of complicated childbirth and prepare them for referral by monitoring their status 2 days before and after childbirth. In this program, the local health workers responsible for monitoring send information via SMS to the 2H2 program center at the primary health centers, who subsequently relay the records to designated referral BEmOC Puskesmas or CEmOC hospital.Citation52 At the hospital level, East Nusa Tenggara province also implemented the Sister Hospital approach, aimed to improve the quality of health workers in guiding childbirth and dealing with obstetric emergencies. Under the approach, local district hospitals in East Nusa Tenggara province are coupled with well-established hospitals in Java. These well-established hospitals are contracted to send specialist doctors or final-year residents to provide basic and emergency maternal health care services and on-the-job training for health workers at the partner hospitals and health centers. The Sister Hospital approach managed to increase the availability of 24-hour obstetric care at the participating district hospitals.Citation53

The present study provides a multiyear trend in maternal health service utilization, which can be used as a benchmark for evaluation of recently launched Indonesia’s national health insurance program, the JKN. The program started in January 2014 with the ambitious goal to cover all Indonesian population by 2019. It consolidates all existing financial protection schemes into a single provider. The combined schemes include the pro-poor social insurance scheme (Askeskin or later known as Jamkesmas), scheme for government employee (Askes) and military personnel (ASABRI), mandatory private sector insurance (Jamsostek), local government-run insurance programs (Jamkesda), as well as specialized scheme for maternal health called Jampersal. In JKN, government fully subsidies the monthly premium for poor and near-poor, while the rest of the population is required to pay monthly premium on a mandatory basis. JKN provides a comprehensive continuum of care for maternal and newborn services, consisting of family-planning counselling and services, a minimum of four ANC visits, services for normal and complicated pregnancy and childbirth, as well as postpartum care.Citation54

The previous insurance schemes had varying experiences. Askeskin increased service utilization by the poor; however, it also increased out-of-pocket spending.Citation55 Jampersal had a limited effect in increasing maternal health service utilization because of widespread perception of the benefit and quality,Citation18 as well as the nonexistence of funding for referral transportation to address accessibility issue.Citation18,Citation56,Citation57 The current Jampersal scheme within the newly established JKN program covers ambulance service to close the gap in geographical accessCitation58 and geographical inequity. Experiences from other countries such as India, Cambodia, and Ghana showed that transportation is an important determinant and including transportation cost in financial protection scheme significantly improves access to maternal health care services.Citation59–Citation62 In addition, JKN provides opportunity for monitoring and improving the quality of care, especially in private sector facilities.Citation63 However, there are criticisms that JKN is concentrating more on hospital-level clinical services than on community-level preventive and promotive services.

Finally, one interesting finding from the study is that demand-side financing program in Indonesia did not result in overutilization of c-section services, as observed in other settings.Citation64 C-section rate in Indonesia of 16% falls just slightly above WHO conservative recommendation of 10%–15%.Citation65 This might also be another indication of persistent low utilization of health care in Indonesia in general.Citation46,Citation66

Strength and limitations

The current study is the first to explore the trend in maternal utilization and equity over time in Indonesia. The use of concentration index is a better way to measure inequity and hopefully can reflect the real situation in the country. However, this study also has some limitations. First, the recall period in the six IDHS surveys varied between 3 and 5 years. This long recall period might introduce bias and affect the accuracy of the information provided by the respondents. Second, as the latest data used were from 2012 IDHS, the more recent changes in access or equity could not be captured in this study.

Conclusion and recommendation

The current study indicates potential health gains with improved social determinants of health in Indonesia, which at the same time also reduces health inequities. However, access inequity still persists across asset quintile groups and across regions. Indonesian government needs to continue closing this gap and finding innovative ways to monitor progress, in which DHS data can be an aid. Comprehensive health insurance program introduced in 2014 has the potential to do this, by improving coverage and quality of health care services and lowering the financial barrier to access the care. With the increasing role of private sector, especially solo providers, it is important to consider ways to include them in the scheme, as well as to monitor and improve the quality of care they deliver.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

No separate budgetary allocation was deployed for this study. All the authors dedicated their additional working hours to develop this manuscript. The authors also kindly acknowledge the European Union funded SHARE project at icddr,b to provide the publication charge. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- StarrsASafe motherhood initiative: 20 years and countingLancet200636895421130113217011924

- StarrsAThe Safe Motherhood Action Agenda: Priorities for the Next DecadeWashington, DCThe World Bank1998

- KunstAEHouwelingTA global picture of poor-rich differences in the utilisation of delivery careStud Health Serv Organ Policy200117293311

- MurraySFHunterBMBishtREnsorTBickDDemand-side financing measures to increase maternal health service utilisation and improve health outcomes: a systematic review of evidence from low-and middle-income countriesJBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep2012105841654567

- GwatkinDRReducing Health Inequalities in Developing CountriesWashington, DCWorld Bank2002

- KawachiISubramanianSAlmeida-FilhoNA glossary for health inequalitiesJ Epidemiol Community Health200256964765212177079

- Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development GoalsSixty-eighth session of the United Nations General AssemblyUnited Nations2014 http://undocs.org/A/68/970Accessed January 29, 2017

- Sustainable Development Solutions NetworkIndicators and a monitoring framework for the sustainable development goals Launching a data revolution for the SDGs2015Sustainable Development Solutions Network Available from: http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/FINAL-SDSN-Indicator-Report-WEB.pdfAccessed December 5, 2017

- SuryadarmaDWidyantiWSuryahadiASumartoSFrom Access to Income: Regional and Ethnic Inequality in IndonesiaJakartaSMERU Research Institute2006

- MahendradhataYTrisnantoroLListyadewiSThe Republic of Indonesia Health System ReviewHortKPatcharanarumolWHealth Systems in TransitionIndiaWorld Health Organization2017

- HodgeAFirthSMarthiasTJimenez-SotoELocation matters: trends in inequalities in child mortality in Indonesia. Evidence from repeated cross-sectional surveysPLoS One201497e10359725061950

- World Bank, UKAidAccelerating improvement in maternal health: why reform is neededIndonesia Health Sector ReviewWashington, DCWorld Bank, UKAid2010

- World Bank GroupLife expectancy at birth, total (years) Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?view=chartAccessed June 14, 2017

- Bureau of Statistics Indonesia, National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Ministry of Health Indonesia, ICF InternationalIndonesia Demographic and Health Survey2012JakartaBureau of Statistics Indonesia, National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Ministry of Health Indonesia and ICF International2013

- ArcayaMCArcayaALSubramanianSInequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theoriesRevista Panamericana de Salud Pública201538126127126758216

- BravemanPWhat are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clearPublic Health Rep (Washington, DC: 1974)2014129Suppl 258

- FrankenbergEThomasDWomen’s health and pregnancy outcomes: do services make a difference?Demography200138225326511392911

- AchadiELAchadiAPambudiEMarzoekiPA study on the implementation of jampersal policy in Indonesia Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) discussion paperWashington, DCWorld Bank Group2014 Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/20740 License

- ChomitzKMWhat Do Doctors Want?: Developing Incentives for Doctors to Serve in Indonesia’s Rural and Remote AreasWashington, DCWorld Bank Publications1998

- MelialaAHortKTrisnantoroLAddressing the unequal geographic distribution of specialist doctors in Indonesia: the role of the private sector and effectiveness of current regulationsSoc Sci Med201382303423453314

- HidayatBMundiharnoNemecJRabovskajaVRozannaCSSpatzJFinancial Sustainability of the National Health Insurance in Indonesia: A First Year ReviewJakartaIndonesian-German Social Protection Programme (SPP)2015

- HattLStantonCMakowieckaKAdisasmitaAAchadiERonsmansCDid the strategy of skilled attendance at birth reach the poor in Indonesia?Bull World Health Organiz20078510774782

- RahmanANishaMKBegumTAhmedSAlamNAnwarITrends, determinants and inequities of 4+ ANC utilisation in BangladeshJ Health Popul Nutr2017361228086970

- FilmerDPritchettLHEstimating wealth effects without expenditure data – or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of IndiaDemography200138111513211227840

- KakwaniNCOn the measurement of tax progressivity and redistributive effect of taxes with applications to horizontal and vertical equityAdv Econometrics19843149168

- StataCorpLStata data analysis and statistical SoftwareSpec Ed Rel200710733

- CallisterLCEdwardsJESustainable development goals and the ongoing process of reducing maternal mortalityJ Obstetric Gynecologic Neonatal Nurs2017463e56e64

- Joint Committee on Reducing Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Indonesia; Development S, and Cooperation; Policy and Global Affairs; National Research Council Indonesian Academy of Sciences. The Indonesian Healthcare SystemReducing Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Indonesia: Saving Lives, Saving the FutureWashington, DCNational Academies Press2013

- ErlyanaEDamrongplasitKKMelnickGExpanding health insurance to increase health care utilization: will it have different effects in rural vs urban areas?Health Policy2011100227328121168932

- Asian Development BankAsian Development Outlook 2016: Asia’s Potential GrowthManilaAsian Development Bank2016

- AhmedSCreangaAAGillespieDGTsuiAOEconomic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countriesPLoS One201056e1119020585646

- KrukMEPrescottMRGaleaSEquity of skilled birth attendant utilization in developing countries: financing and policy determinantsAm J Public Health200898114214718048785

- TitaleyCRDibleyMJRobertsCLFactors associated with under-utilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007BMC Public Health201010148520712866

- United NationsThe Millennium Development Goals Report 2015New YorkUnited Nations2015

- McKinnonBHarperSKaufmanJSDo socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal mortality reflect inequalities in coverage of maternal health services? Evidence from 48 low and middle-income countriesMaternal Child Health J2016202434446

- MulhollandESmithLCarneiroIBecherHLehmannDEquity and child-survival strategiesBull World Health Organiz2008865399407

- KristiansenSSantosoPSurviving decentralisation? Impacts of regional autonomy on health service provision in IndonesiaHealth Policy200677324725916125273

- Jimenez SotoELa VincenteSClarkAInvestment case for improving maternal and child health: results from four countriesBMC Public Health201313160123800035

- HeywoodPChoiYHealth system performance at the district level in Indonesia after decentralizationBMC Int Health Hum Rights2010101320205724

- Central Bureau of Statistics Indonesia, National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Ministry of Health Indonesia, ICF InternationalIndonesia Demographic And Health Survey2012JakartaCentral Bureau of Statistics Indonesia, National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Ministry of Health Indonesia, and ICF International2013

- AndersonIMelialaAMarzoekiPPambudiEThe Production, Distribution, and Performance of Physicians, Nurses, and Midwives in Indonesia: an UpdateWashington, DCWorld Bank2014156

- HeywoodPHarahapNPHealth facilities at the district level in IndonesiaAust N Z Health Policy20096113

- HeywoodPFHarahapNPHuman resources for health at the district level in Indonesia: the smoke and mirrors of decentralizationHum Resour Health200971619192269

- National Institute of Health Research and Development (NIHRD)Ministry of Health Indonesia. Indonesia Basic Health Research 2010JakartaIndonesia. Ministry of Health2013

- WatersHSaadahFPradhanMThe impact of the 1997–98 East Asian economic crisis on health and health care in IndonesiaHealth Policy Plann2003182172181

- HidayatBThabranyHDongHSauerbornRThe effects of mandatory health insurance on equity in access to outpatient care in IndonesiaHealth Policy Plann2004195322335

- BarberSLGertlerPJHarimurtiPDifferences in access to high-quality outpatient care in IndonesiaHealth Affairs (Project Hope)2007263w352w36617389632

- SupratiktoGWirthMEAchadiECohenSRonsmansCA district-based audit of the causes and circumstances of maternal deaths in South Kalimantan, IndonesiaBull World Health Organiz2002803228235

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia: Menuju Masyarakat Sehat yang Mandiri dan BerkeadilanKinerja Dua Tahun Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia 2009–2011JakartaKementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia2011

- Minister of HealthMinister of Health regulation No. 69 of 2016 on the implementation of mandatory service for specialist doctors to achieve universal coverage for specialist care in IndonesiaJakartaMinistry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Available from: http://ditjenpp.kemenkumham.go.id/arsip/bn/2017/bn226-2017.pdfAccessed September 9, 2017

- PertiwiIMPerencanaan Program Pemenuhan Dokter Spesialis Dasar di RSD Balung Kabupaten Jember Tahun 2016Digital Repository Universitas JemberJemberUniversitas Jember2017

- PardosiJFParrNMuhidinSLocal government and community leaders’ perspective on child health and mortality and inequity issues in rural Eastern IndonesiaJ Biosoc Sci201749112314627126276

- Center for Health Policy and Management, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah MadaEvaluation workshop for sister hospital and performance and management leadership program in East Nusa Tenggara2014 Available from: http://mutukia-ntt.net/index.php/laporan/sister-hospitalAccessed September 9, 2017

- Minister of HealthMinister of Health regulation No. 52 of 2016 on standard tariffs for health services in the national health insurance implementationJakartaMinistry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Available from: http://djsn.go.id/storage/app/uploads/public/58d/487/cdd/58d487cdd4630003169427.pdfAccessed September 9, 2017

- SparrowRSuryahadiAWidyantiWSocial health insurance for the poor: Targeting and impact of Indonesia’s Askeskin programmeSoc Sci Med20139626427123121857

- ErpanLNLaksono TrisnantoroTKoordinasi pelaksanaan pembiayaan program kesehatan ibu dan anak di Kabupatek Lombok Tengah Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat tahun 2011Jurnal Kebijakan Kesehatan Indonesia2012114251

- NoerdinETransport, health services and budget allocation to address maternal mortality in rural IndonesiaTransp Commun Bull Asia Pac201484114

- Minister of HealthMinister of health regulation No. 71 of 2016 on the technical guideline for the use of non-infrastructural special health budget for the budget year2017JakartaMinistry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Available from: http://hukor.kemkes.go.id/uploads/produk_hukum/PMK_No._71_ttg_JUKNIS_Penggunaan_DAK_NONFISIK_Bidang_Kesehatan_TA_2017_.pdfAccessed September 9, 2017

- ArsenaultCFournierPPhilibertAEmergency obstetric care in Mali: catastrophic spending and its impoverishing effects on householdsBull World Health Organiz2013913207216

- AtuoyeKNDixonJRishworthAGalaaSZBoamahSALuginaahICan she make it? Transportation barriers to accessing maternal and child health care services in rural GhanaBMC Health Serv Res201515133326290436

- MohantySKSrivastavaAOut-of-pocket expenditure on institutional delivery in IndiaHealth Policy Plann2012283247262

- HoremanIr PNarinDVan DammeSWImproving access to safe delivery for poor pregnant women: a case study of vouchers plus health equity funds in three health districts in CambodiaRichardFWitterSDe BrouwereVReducing financial barriers to obstetric care in low-income countries: studies in health services organisation & policy no. 24AntwerpITG Press2008225255

- BennettSBloomGKnezovichJPetersDHThe future of health marketsGlobalization Health20141015124961396

- AnwarINababanHYMostariSRahmanAKhanJATrends and inequities in use of maternal health care services in Bangladesh, 1991–2011PLoS One2015103e012030925799500

- BetranATorloniMZhangJGülmezogluAWHO Statement on caesarean section ratesBJOG2016123566767026681211

- HarimurtiPPambudiEPigazziniATandonAThe nuts & bolts of Jamkesmas Indonesia’s government-financed health coverage program for the poor and near-poorUNICO Studies Series No 8Washington DCWorld Bank2013