Abstract

Postnatal depression (PND) has negative effects on maternal well-being as well as implications for the mother–infant relationship, subsequent infant development, and family functioning. There is growing evidence demonstrating that PND impacts on a mother’s ability to interact with sensitivity and responsiveness as a caregiver, which may have implications for the infant’s development of self-regulatory skills, making the infant more vulnerable to later psychopathology. Given the possible intergenerational transmission of risk to the infant, the mother–infant relationship is a focus for treatment and research. However, few studies have assessed the effect of treatment on the mother–infant relationship and child developmental outcomes. The main aim of this paper was to conduct a systematic review and investigate effect sizes of interventions for PND, which assess the quality of the mother–infant dyad relationship and/or child outcomes in addition to maternal mood. Nineteen studies were selected for review, and their methodological quality was evaluated, where possible, effect sizes across maternal mood, quality of dyadic relationship, and child developmental outcomes were calculated. Finally, clinical implications in the treatment of PND are highlighted and recommendations made for further research.

Introduction

Approximately one in ten women suffers from postnatal depression (PND).Citation1–Citation3 BeckCitation4 reported that the best predictor of PND was depression in the antenatal period. A recent review identified a number of postnatal factors placing women at increased risk to continued depressive symptoms, including younger maternal age, poor education attainment, historical episodes of depression, antidepressant use during pregnancy, child developmental problems, low parental self-efficacy, poor relationship, and the occurrence of stressful life events.Citation5 Psychosocial factors (ie, poverty, marital discord, life stressors) are thought to be more predictive of vulnerability to PND than biological or hormonal causes.Citation1

PND has varied onset, chronicity, clinical presentation, and course relative to major depression and other mood disorders in the postpartum period, including postnatal blues and puerperal psychosis.Citation6 Biopsychosocial models highlight the complexity and interaction between multiple systems implicated in PND. The model by Milgrom et alCitation1 details vulnerability factors, precipitating factors (including those factors which may trigger PND onset: stress levels, stress-moderating variables of social support, and coping skills), and biological factors. The model also explains that sociocultural factors may play a role in exacerbating and maintaining PND and they account for heterogeneity in vulnerability to experiencing PND across women.

An episode of PND generally lasts from 2 months to 6 months in duration and as long as 1 year in some cases.Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), fourth edition, women meet diagnostic criteria for PND if the onset is within the first 4 weeks postpartum, although this onset period has been extended in clinical practice with reports that 50% of cases start within 3 months and 75% of cases within 7 months.Citation8 The revised criteria in the DSM-V included a new specifier of mood episodes beginning in pregnancy.Citation9 These criteria make limited reference to the infant, although the need for recognition of symptoms relating specifically to birth, labor, and other aspects of being a new parent has been identified elsewhere.Citation10

The estimated cost of care alone between women with PND and those without PND in a British community sample is significant, reaching a mean cost of £505.70 for mothers without PND and £786.20 for mothers with PND – a significant (P=0.01) mean cost difference of £280.50.Citation11 Petrou et alCitation11 have recommended that these are conservative estimates and that the excess cost is substantially more for women experiencing extended episodes of PND. Notwithstanding, there are further cost implications in terms of child and adolescent services accessed due to the increased risk associated with having a parent with PND. Treatment is, therefore, a major public health concern and the one which spans both maternal and infant mental health.Citation12

Considerable evidence suggests that PND has profound and widespread effects on the mother,Citation13 the mother–infant relationship,Citation14,Citation15 and serious implications for subsequent infant developmentCitation16–Citation18 and family well-being.Citation19 Research has established that PND can affect the quality of parenting.Citation20–Citation22 In the context of PND, difficulties in practical parenting practices related to breastfeeding,Citation23–Citation25 sleep,Citation26–Citation28 infant health care,Citation29 and safety practicesCitation24,Citation25,Citation30,Citation31 have been reported. Following an episode of PND, women are predisposed to future risk of depressive episodes with subsequent children. Crucially, the first year is an important period for infants to develop self-regulatory skills.Citation32,Citation33 Adaptive development of self-regulatory skills in the infant is promoted by sensitive and responsive caregiving. PND directly impacts on a mother’s ability to sensitively respond to her baby; thus, the quality of the dyadic relationship is also affected.

Interventions focusing exclusively on maternal depression may not be sufficient alone to buffer against the risks to infant development.Citation34–Citation36 In many instances, maternal mood may improve, but the intergenerational transmission of risk may continue to manifest. Conceptualizing the depressive episode within the context of the perinatal period may promote adaptive developmental pathways in the infant. It is therefore necessary to measure outcomes in order to understand if interventions for PND exert a protective effect on the mother–infant relationship and infant development in addition to maternal mood.

Intergenerational transmission of risk to children of women with PND

Goodman and GotlibCitation37 highlighted the need for a developmental model, which explains the transmission and manifestation of vulnerability in infants. The nature of the association between PND and infant development is especially complicated by limited understanding of the full impact and risk of maternal mood and cognitions on infant developmental pathways.

In their integrated model, Goodman and GotlibCitation37 detail how the effects of PND are implicated across the intergenerational gap. The model reflects the complex interplay between quality of parenting and several mechanisms (ie, heritability of depression, neuroregulatory mechanisms, exposure to negative maternal cognitions, behavior and affect, and sociodemographic conditions) and moderating risk factors (ie, paternal health/involvement, course and timing of depression, and individual child characteristics) which influence the developing infant (see Goodman and GotlibCitation37 for a description of the model).

Effect of PND on infant development

Evidence suggests that PND in the parent may contribute to serious effects on infant cognitive and emotional development and is associated with later psychopathology and atypical development.Citation38–Citation40,Citation44

Grace et alCitation41 highlighted that the most significant effects of PND were on cognitive development including language development and intelligence. However, effects varied with characteristics of children involved, including sex and contextual factors as indicated by the aforementioned model. They also suggested that timing and course of PND were more pervasive in their effects on child development.

Research using the face-to-face video interaction paradigm has demonstrated that mothers with PND are more negative and their infants less positive than nondepressed mother–infant dyads.Citation42

Longitudinal studies have also shown a predictive link between early PND and problems much later in development.Citation17,Citation43 Milgrom et alCitation44 demonstrated the role of maternal responsiveness in atypical developmental patterns and increased temperamental difficulties in infants of mothers with PND at 48 months postpartum. They also found that full IQ scores were lower in children of mothers with PND, demonstrating the lasting effects of PND occurring early in the postpartum period. Recent systematic reviews by Kingston et alCitation45 and Kingston and ToughCitation46 evaluated longitudinal research of the effects of maternal distress, including postnatal distress, on infants and school-aged children. They reported particular effects of postnatal maternal distress on both infantCitation45 and school-aged childCitation46 cognitive and socio-emotional development. They also summarized small-to-moderate effects of postnatal maternal distress on the behavior of school-aged children.Citation46

The mother–infant relationship

Developmental literature has highlighted the importance of early influence at protecting and promoting development. The infant–caregiver relationship has been widely recognized to play an important role in child development.Citation47 Murray and CooperCitation39,Citation40 suggested that the effects of PND on infant development were mediated through an association with maternal cognitions and maladaptive parenting practices. Research by Stein et alCitation48 demonstrated that disturbances in maternal cognitions of women with PND may play a causal role in the negative effects on the mother–infant relationship.

Parental ability to regulate an infant’s emotional state plays a key role in helping children to develop strategies for self-regulation.Citation22,Citation49–Citation51 GerhardtCitation50 summarized that the implications of failure of the caregiver to respond appropriately or “good enough” to her infant’s needs had an impact at the neuro-chemical level of prolonged increase of cortisol levels on the infant. GerhardtCitation50 reviewed evidence that prolonged levels of cortisol in early infancy have consequences for neural systems implicated in how infants tolerate stress later in life, namely the prefrontal cortex and Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Emerging imaging research completed with adult children of women with PND captured a significant association between their attachment security at 18 months and neural responding at 22 years of age.Citation52 Specifically, the research found increased activation in prefrontal areas and decrease in activation of neural regulation of positive affect. Further research identified that compared with controls, women with PND are less able to identify happy faces potentially leading to decreased responsiveness toward their infants.Citation53

Van Den BoomCitation54 reported that educating vulnerable parents on how to respond appropriately and “optimally” to their temperamentally reactive infants was central to forming secure attachment bonds with their infants. This secure attachment, which develops between the mother and infant, also illustrates that the care the infant receives can impact in a protective manner on the developing child. Consequently, it seems that at least optimal parenting is a key feature in a parent’s (namely the mother’s) ability to regulate and soothe his/her infant during periods of distress.Citation50

Interventions focusing on the mother–infant relationship

There is a body of research investigating various treatment approaches for PND. Within the available literature, several approaches have been identified and have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, including various antidepressant treatments,Citation55,Citation56 antenatal group interventions,Citation57 psychoeducation,Citation58,Citation59 cognitive behavior therapy (CBT),Citation60,Citation61 interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT),Citation34,Citation62,Citation63 and interventions focusing on the mother–infant relationshipCitation64–Citation66 and baby massage.Citation67,Citation68 Indeed, there are several comprehensive literature reviews on the evidence base of different interventions.Citation12,Citation69–Citation73

However, within this literature, a poverty of interventions measuring outcomes relating to the mother, her relationship with the infant, and infant development has been identified. The majority of reviews on the subject have explored efficacy in relation to maternal mood. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that the treatment of PND alone is not sufficient to improve the mother–infant relationship as well as child development.Citation34,Citation69 Given that PND affects the mother, her relationship with the infant, as well as the infant’s development and well-being, a systematic review exploring the impact of interventions on these outcomes was clearly indicated.

Assessment of child outcomes and dyadic relationship in interventions for PND

A significant proportion of PND treatment literature has focused on the mother’s depression in isolation, with few studies assessing the quality of the dyadic relationship as well as child developmental outcomes. They do not reflect mechanisms or moderators proposed by Goodman and Gotlib.Citation37 Therefore, it is difficult to determine what impact treatment has beyond outcomes associated with maternal mood.

While there is an extensive literature of evaluation studies on various interventions for PND, little is known about the benefit of interventions to the quality of the mother–infant relationship and moreover, child developmental outcomes. Poobalan et alCitation74 addressed this issue through an earlier review of treatments for PND, which focused on the mother–infant dyad relationship. Outcomes were discussed in terms of child outcomes. They noted some support for dyadic-focused interventions in improving child outcomes; however, the evidence was equivocal. In addition, Poobalan et al’s reviewCitation74 did not calculate effect sizes. In contrast, the present review extends the review by Poobalan et alCitation74 by reporting on effect sizes, updating the search period from 1999 to 2014, inclusion of other therapies (antidepressant medication), and rigorous quality assessment, using the Clinical Tool for Assessment of Methodology (CTAM)Citation75 categories including allocation, assessment, control groups, analysis, and treatment. Most importantly, the present review considers the impact of treatments on maternal depression symptoms in addition to child outcomes.

The aims of the present systematic review were to evaluate all trials reported in the literature since 1999 and to evaluate intervention research, which has included outcomes measuring the quality of the mother–infant relationship and/or child developmental outcomes in addition to maternal mood.

Method

Search strategy

The literature search included publications from 1999 to 2014, since an earlier review by Poobalan et alCitation74 reviewed studies from the 1990s to 2005, using a standard assessment adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration and Jadad Scale.Citation76 The following databases were searched: PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and Maternity and Infant Care. Additional searches were run using the aforementioned databases and PubMed for the dates between 2012 and 2014. Boolean searches on MeSH were conducted using combinations of the following (and related) terms: (“depression, postpartum” [MeSH Terms] OR “depression, postpartum” [MeSH Terms]) AND ((“therapy” [Subheading] OR “therapy” [All Fields] OR “treatment” [All Fields] OR “therapeutics” [MeSH Terms] OR “therapeutics” [All Fields]) OR (“Intervention (Amstelveen)” [Journal] OR “intervention” [All Fields] OR “Interv Sch Clin” [Journal] OR “intervention” [All Fields])) AND ((“mother–child relations” [MeSH Terms] OR (“mother–child” [All Fields] AND “relations” [All Fields]) OR “mother–child relations” [All Fields] OR (“mother” [All Fields] AND “child” [All Fields] AND “relations” [All Fields]) OR “mother child relations” [All Fields]) OR (“child development” [MeSH Terms] OR (“child” [All Fields] AND “development” [All Fields]) OR “child development” [All Fields] OR (“infant” [All Fields] AND “development” [All Fields]) OR “infant development” [All Fields])) AND (“1999/01/01” [PDAT]: “2014/12/31” [PDAT]), Filters: Journal Article, From January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2015, Humans). All titles and abstracts were initially scanned for relevance.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were considered if they included a treatment or intervention which was delivered in the postnatal period, and if the primary outcomes assessed maternal depression and mother–infant interaction and/or child outcomes. Both single-group and randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs were considered for inclusion. A further inclusion criterion was that participants were experiencing low mood as indicated by a screening tool (ie, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [EPDS]) or a professional diagnosis of depression.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they were single-case designs, reviews, book chapters, and/or discussion papers, not in the English language, and not peer reviewed.

Evaluation of quality of trial methodology

The CTAM, an assessment tool used to evaluate the quality of psychotherapeutic trials,Citation75 was used in the present study because of its comprehensiveness in covering the six main areas of trial design, including sample size and recruitment method, allocation to treatment, assessment of outcomes, control groups, description of interventions, and analysis of data. There are a total of 15 items. Scores range from 0 to 100; scores over 65 are regarded as good quality.

Effect sizes indicate the magnitude of difference between two groups. In this review, they were also calculated separately for maternal mood, quality of dyadic relationship, and child developmental outcomes.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were considered as small if between 0.2 and 0.3, medium if between 0.4 and 0.7, and as large if equal to or greater than 0.8. As suggested by Cohen,Citation77 effect sizes were calculated individually given the heterogeneity of outcome measures and interventions. Effect sizes have only been calculated in studies where means and standard deviations were reported. Effect sizes have not been calculated in previous reviews of this literature.

Results

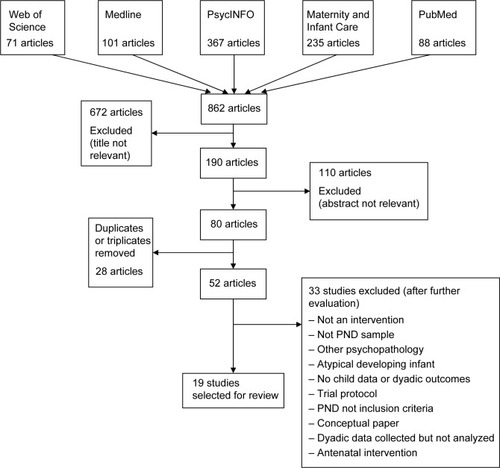

The initial search returned 862 articles. Six hundred and seventy-two articles did not meet inclusion criteria on the basis of a review of the title and/or abstract. A further 143 articles were excluded after more detailed examination of the title and abstract. Twenty-eight articles were removed for being duplicates or triplicates leaving 19 studies to be evaluated () for a schematic diagram of the literature search. Only three studiesCitation34,Citation61,Citation64 assessed both the quality of the dyad relationship and child outcomes. Although there was a high degree of heterogeneity across studies and measures used for assessment, effect sizes for different outcomes (maternal mood, mother–infant relationship, child developmental outcomes) were calculated where possible.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of literature search for studies on treatment for PND with outcomes assessing mother–infant interaction and/or child outcomes.

Location and sample

From the 19 studies included in the review, nine were carried out in the USA, five in the UK, two in the Netherlands, two in Australia, and one in Canada.

Participant characteristics

Of the 19 studies, ten were carried out with a multiparous sample and three with a primiparous sample, and six of the studies did not report parity. There was high variability across study client inclusion criteria regarding how depressive diagnosis was determined. Thirteen studies included participants with a professional diagnosis of PND, and six studies included participants with probable diagnosis through public health screening. There were also differences across characteristics of participants in terms of severity of depression, marital status, and age of baby ().

Table 1 Participant characteristics including marital status, age of baby and mother, and level of depression (at baseline) across all studies

Treatment type, session length, and total duration

The types of interventions evaluated in this review varied greatly with respect to their focus. For example, some interventions focused on the dyadic interaction, whereas others focused on maternal depression. Clark et alCitation65,Citation78 evaluated mother–infant therapy group (M-ITG), a relationship-focused intervention grounded in interpersonal, psychodynamic, and family system approaches. The M-ITG intervention focuses on a) providing therapeutic intervention and peer support, b) addressing infant emotional regulation and social engagement, and c) promoting sensitive interaction in the dyad. In their 2003 study, Clark et alCitation65 compared M-ITG with IPT, which involves identifying interpersonal patterns contributing to symptoms of PND.

Forman et alCitation34 and Mulcahy et alCitation62 also examined IPT and described it as focusing on social role transitions (ie, transition to parenthood) as well as loss and grief in addition to focusing on individual interpersonal aspects. Infant massage, which involves administering various massage techniques to an infant’s body while adjusting strokes according to infant responses, was also evaluated.Citation67,Citation68,Citation79

A further intervention focusing on the dyad relationship, called interaction coaching intervention, was evaluated by Horowitz et al.Citation80 The intervention is designed to strengthen the dyadic relationship and focuses on a) promoting maternal responsiveness, b) guiding mother to make eye contact with infant, c) responding to pauses (ie, imitation, facial expression, and tone), d) practicing through trial and error, e) reinforcing maternal-sensitive responsiveness, and f) praising success.

Kersten-Alvarez et alCitation81 also evaluated a mother–infant intervention focusing on enhancing quality of dyadic interaction, through improving maternal sensitivity using video feedback and where needed, using modeling behavior, cognitive restructuring, support, and baby massage. Jung et alCitation66 investigated the efficacy of a further dyadic-focused intervention. Keys to Caregiving, aims to facilitate sensitive responding to infant behaviors through enhancing understanding of the meaning of different infant behaviors. The intervention involved practice with the infant during the session and at home. Keys to (caregiving) Capital sessions included understanding of infant states, infant behaviors, infant cues, modulation, and feeding.

In their RCT, Cooper et alCitation82 compared routine care (health visiting with no additional input) with CBT, nondirective counseling, and psychodynamic therapy. Nondirective counseling provided women with the opportunity to discuss feelings of current concerns (ie, financial, relational – partner/infant). CBT was tailored toward the mother’s management of her infant (ie, feeding, sleep) and the quality of the dyadic interaction. Within the CBT sessions, a woman was also encouraged to problem solve in a systematic way, and examine patterns of thinking about her infant and herself as mother. Psychodynamic therapy utilizes techniques aimed at understanding mother’s representation of infant and relationship with infant promoted by exploring aspects of mother’s early attachment history. Two antidepressant medications (nortriptyline and sertraline) were also evaluated.Citation55

The review of all studies also showed that session lengths ranged from 15 minutes to 2 hours, and total treatment duration ranged from three to 12 sessions. Mode of delivery included both individual and group delivery as well as mixed individual and group. A summary of type of treatment, session length, and treatment duration, CTAM scores, and domains of assessment (maternal affect, dyad relationship, and child development) across all studies is presented in .

Table 2 Characteristics of studies assessing interventions for PND which include either dyad or child developmental outcomes

Methodological quality

A summary of CTAM scores across all studies assessed is presented in . Overall, most studies (eleven of the 19 studies) included in the review had a CTAM score below 65, which is described as inadequate by the authors of the CTAM.Citation75

Sample

Most studies (12/19) used a convenience sample. Nine of the 19 studies had a sample size greater than 27 in each treatment group.Citation34,Citation61,Citation64,Citation67,Citation80–Citation84 Numbers of less than 27 in each group are regarded as inadequate and do not score on the CTAM. Small sample sizes are a long-standing limitation within the PND literature. A large proportion of studies with PND populations failed to recruit to target, and as such they were underpowered. This is a difficulty experienced across trials.

Allocation

While most studies described whether there was true random allocation or minimization allocation across treatment groups, only ten studies described the process of randomization.Citation55,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation67,Citation80,Citation82,Citation83,Citation85,Citation86 Furthermore, four studies also indicated that the process of randomization was carried out independently of the research team.Citation55,Citation62,Citation83,Citation85

Assessment

All of the studies used standardized assessments to measure outcomes. All but three studiesCitation66,Citation68,Citation86 had assessors who were independent of treatment delivery (ie, they were not the therapist on the trial). Eight studies reported that assessments were carried out blind to treatment group allocation.Citation34,Citation61,Citation67,Citation80–Citation83,Citation85 However, only two studiesCitation68,Citation80 described the method of rater blinding, while only one studyCitation68 reported verification of rater blinding.

Control groups

While most studies utilized a RCT design, three studiesCitation34,Citation67,Citation83 reported using both, no treatment or waitlist control (WLC) group and a control group that controlled for nonspecific effects (ie, nondepressed comparison group).

Analysis

All studies conducted appropriate analyses given their design and sample sizes. One studyCitation34 employed an intention-to-treat analysis (including all participants as randomized), and six studies had attrition of less than 15%.Citation61,Citation62,Citation80,Citation82,Citation84,Citation85 The remaining studies did not handle drop-outs appropriately, and had attrition of greater than 15% or inappropriate sample sizes (ie, less than 27 participants in each group).

Active treatment

All interventions employed were psychotherapy or psychosocial interventions with the exception of one study,Citation55 which was an evaluation of two types of antidepressant medications. Nine of the studies provided an adequate description of the treatment, reported the use of a protocol or manual, as well as an assessment of adherence to the protocol.Citation62,Citation64,Citation65,Citation78,Citation81–Citation83,Citation85,Citation86

Maternal mood, dyadic relationship, and developmental outcomes

Outcome measures

Various outcome measures were used across the studies to evaluate the efficacy of interventions in the domains of maternal affect, dyad relationship, and child development ().

Maternal mood

Studies used either the Beck Depression Inventory or the EPDS to assess maternal mood, with the exception of three studies, which used the Hamilton Rating Depression Scale.Citation55,Citation62,Citation83 The largest effect sizes, though moderate in terms of effectiveness of treatment on improvement in maternal mood, were reported by Horowitz et alCitation80 and Clark et alCitation65 ( presents the effect sizes). In their evaluation of the efficacy of a behavioral intervention delivered by advanced practice nurses and research assistants, which involved coaching designed to promote maternal responsiveness, Horowitz et alCitation80 reported that women who had received the behavioral coaching showed a significantly higher level of responsiveness posttreatment. Clark et alCitation65 investigated the efficacy of a 12-week, manualized M-ITG compared with WLC: women allocated to the M-ITG showed significantly fewer depressive symptoms, and experienced their infants as more reinforcing and parenting more rewarding.

Table 3 Means, SDs, Cohen’s d, and effect sizes on measures of maternal depression and dyad measures across studies

Smaller effect sizes () were calculated across several other studies.Citation62,Citation64,Citation67,Citation78,Citation82 Three studies reported on evaluations of IPT: Mulcahy et alCitation62 in an RCT comparing group IPT with treatment as usual (TAU), Clark et alCitation65 in an RCT comparing M-ITG and IPT with WLC, and Beeber et alCitation83 in an RCT comparing IPT + parental enhancement (PE) with an attention control health education condition. While a greater effect size was calculated for M-ITG compared to IPT in Clark et al’sCitation65 study, an overall greater effect size was reported by Mulcahy et al.Citation62

Cooper et alCitation82 compared counseling, psychodynamic therapy, and CBT with TAU. The largest effect size was calculated for psychodynamic therapy. Psychodynamic therapy was associated with significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared with TAU; however, the effects were not maintained at 9-month follow-up. No significant differences were found in symptoms of depression between women who took part in an intervention working on the quality of the dyadic relationship compared with mothers receiving telephone parenting support only.Citation64

Goodman et alCitation85 evaluated the efficacy of perinatal dyadic psychotherapy (PDP), designed to reduce symptoms of depression and improve the mother–infant relationship. Using an RCT design, they compared PDP with a control condition receiving telephone monitoring of symptoms. Both groups reported significant improvements in their depressive symptoms.

Three studies evaluated different delivery modalities of baby massage.Citation67,Citation68,Citation79 No significant differences were found across measures of maternal mood between comparison groups and women receiving baby massage in the studies by O’Higgins et al.Citation67 Onozawa et alCitation68 and Field et alCitation79 did measure developmental but not maternal outcomes (but included women on the basis of formal diagnoses of major depression).

CBT supplemented with a mother–infant module Happiness Understanding, Giving and Sharing (HUGS) was evaluated by Milgrom et al.Citation60 The authors reported signifi-cant reductions in symptoms of depression following CBT and further significant drops in parenting stress following the mother–infant module. Due to missing information, effect sizes for this study could not be calculated. Logsdon et alCitation55 also reported significant reductions in symptoms of depression following 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment (nortriptyline and sertraline).

Mother–infant relationship

Of the 19 studies, 17 assessed dyadic relationship outcomes (). The measures used to assess the dyadic relationship varied widely. The largest effect size on dyadic outcome was calculated for the study by Kersten-Alvarez et al.Citation81 The intervention (video feedback) had a medium effect on index of the quality of interactive behavior.

Clark et al’ studyCitation78 had the second largest effect size calculated in the group that received IPT but only for factor one (Maternal Positive Affect Involvement and Verbalization) of the Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA).Citation87 A later study carried out by Clark et alCitation65 found comparable findings using the PCERA, with the largest effect size calculated for factor one (as above), followed by factor two (Maternal Negative Affect and Behavior), six (Infant Dysregulation and Irritability), and seven (Dyadic Mutuality and Reciprocity).

Beeber et alCitation83 also reported significant outcomes in their investigation of IPT + PE. They reported significant increases in positive involvement in the mothers who received IPT + PE only.

In their uncontrolled study, Jung et alCitation66 reported that post-intervention, infants displayed a marked increase in interest and joy during interaction with their mothers.

In another RCT, mother–infant dyads were either videotaped and given feedback using one of four techniques during eight to ten sessions, including (1) modeling, (2) cognitive restructuring, (3) practical support, and (4) baby massage, or provided with three sessions of practical parenting advice via telephone calls.Citation64 The authors reported that at 6-month follow-up, the treatment group had higher Attachment Q-Set (AQS) scores and maternal sensitivity (on the Emotional Availability Scale [EAS] subscale) than controls. Small effect sizes were calculated for the video feedback intervention on child responsiveness and involvement, as well as maternal structuring and sensitivity EAS subscales. A small effect size was also calculated for the intervention on the AQS. A small effect of IPT on the Maternal Attachment Inventory was also found in Mulcahy et al’sCitation62 RCT investigating the effectiveness of group IPT.

In the study by Horowitz et alCitation80 the relationship-focused behavioral coaching invention (CARE) was found to have a small effect on the quality of the mother–infant relationship, as measured by the Dyadic Mutuality Code. In a recent RCT of the CARE intervention, despite significant reductions in both symptoms of depression and improvements to the mother–infant relationship, there were no significant differences between women receiving the CARE intervention and those allocated to a control group.Citation84

In an RCT examining the effectiveness of baby massage in the treatment of PND, no differences in the quality of the mother–infant relationship (measured by global ratings) were found between women receiving baby massage and those receiving support only at posttreatment.Citation67 However, at 1-year follow-up, depressed dyads who had participated in baby massage had comparable scores of maternal sensitivity with nondepressed dyads, whereas women who had received only support performed significantly less well.

In a double-blind RCT of two antidepressants (nortrip-tyline and sertraline), the authors reported no significant differences in the improvement in the quality of the dyadic interaction on the Child and Caregiver Mutual Regulation Coding Scale.Citation55

With respect to the remaining studies, it was not possible to calculate the effect size of interventions on the mother–infant relationship. In another trial of baby massage, the authors reported significant improvements in mother–infant interaction (assessed by global ratings for mother–infant interactions) in women who received baby massage compared with women who attended a support group only.Citation68

In their RCT, Murray et alCitation61 reported limited short- and long-term improvements in the mother–infant interactive quality following treatment in nondirective counseling, CBT, psychodynamic therapy, or TAU. They reported improvements across all groups in face-to-face mother–infant interactions but no significant differences between groups. However, they did report that women allocated to the control group had higher levels of maternal sensitivity at baseline compared with the other groups. Interestingly, they also reported that women with high levels of social adversity who received counseling were found to have higher levels of maternal sensitivity. No other differences in treatment with respect to the quality of the mother–infant relationship were found.

In the study by Milgrom et alCitation60 which investigated CBT and the adjunct mother–infant intervention, significant marked (self-reported) improvements in the function of mother–infant relationship following the mother–infant adjunct module were reported.

In a pilot RCT comparing Baby Positive Parenting Programme (Baby Triple P), in addition to TAU with TAU only, there were significant improvements in depressive symptoms.Citation86 There was, however, no significant additive effect of Baby Triple P demonstrated across outcomes of maternal mood or dyadic outcomes, measured by the CARE index.Citation86

Finally, Goodman et alCitation85 found no differences in dyadic-related outcomes between women allocated to PDP and those in a control group.

Child development

Four studies measured child developmental outcomes.Citation34,Citation61,Citation64,Citation79 Measures used to assess child development varied making it difficult to compare effect sizes between studies. Across studies, it was reported that infants improved on some subscales but not others ().

Table 4 Means, SDs, Cohen’s d, and effect sizes on measures of child development across studies

Van Doesum et alCitation64 reported that infants in the treatment group (video feedback) were significantly more competent (measured by Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment [ITSEA] subscale scores) compared with infants in the control group.

In an RCT investigating the efficacy of IPT treatment in women with PND, a small effect size was calculated for IPT on Child Behaviour Checklist subscales of internalizing and externalizing.Citation34 No differences in any of the other ITSEA subscales were found. Insufficient data meant that it was not possible to calculate effect sizes for the remaining studies.Citation61,Citation79

In their RCT comparing group baby massage with a rocking group, Field et alCitation79 reported several outcomes related to infant behaviors, including Thoman’s system of sleep recording, salivary cortisol, weight, formula intake, temperament ratings, and urine assays to measure hormones associated with stress. Babies in the massage group were observed to be significantly more awake and less drowsy compared with the rocking group. Crying and cortisol level in the baby massage group also decreased significantly compared with the rocking group. There were also significant changes in temperament. Babies in the massage group were observed to be significantly more sociable, more easily soothed, and less emotional compared with babies who were in the rocking group.

Several child developmental and behavioral outcomes were measured at three time points by Murray et al.Citation61 There was no significant effect of treatment group on early management of infant behavior following treatment (4.5 months). At 18-month follow-up, there was a significant effect of counseling (after controlling for maternal age) on infant emotional and behavioral problems (measured by the Behavioural Screening Questionnaire).Citation88 Five years later, a nonsignificant effect of CBT treatment was found on infant emotional and behavioral problems (measured by Rutter A2 Scale), but there were no differences across interventions in teacher-reported child behavioral difficulties (measured by Preschool Behavior Checklist). There were also no differences across the treatment groups in measures of cognitive development at 18-month (Mental Development Index of the Bayley scales) and 5-year (General Cognitive Index of McCarthey Scales) follow-ups.

Discussion

This is the first review to date to rigorously evaluate the methodological quality of studies using the CTAM, calculate effect sizes (where possible), and compare outcomes related to both maternal mood and child development and/or the dyadic relationship.

Of the interventions reviewed here, those which have focused on the dyad relationship, namely mother–infant therapyCitation78 and a coaching intervention, designed to promote maternal responsiveness,Citation80 had the greatest efficacy at reducing symptoms of PND (where data were available to calculate effect sizes). However, effect sizes of the aforementioned studies for improvements in the quality of the mother–infant relationship were more modest by comparison.

The intervention, which focused on the quality of the dyad relationship, demonstrated the largest effect size with respect to improvement in the quality of the mother–infant relationship. However, this finding was not consistent across all outcomes. While the majority (18/19) of studies measured mother–infant interaction outcomes, only four studies measured child developmental outcomes, and the resulting effect sizes were small. This highlights a limited therapeutic effect across child outcomes, despite overwhelming research evidencing the impact of PND on short- and long-term developmental patterns. In terms of intergenerational transmission of risk to children, it is difficult to determine whether reported improvements in mother–infant relationships were due to improvements in developmental outcomes or improvements in PND, or whether there is a bidirectional link.Citation34,Citation69,Citation74

The findings from this review are consistent with those reported by Poobalan et al,Citation74 an earlier review of eight RCTs aimed at treating PND through targeting the mother–infant relationship. For example, improvements in dyadic interaction do not necessarily lead to an improvement in child developmental outcomes. Interestingly, the size of the intervention effect on maternal outcomes was discrepant with those calculated on measures of infant development and the quality of the mother–infant interaction. These findings suggest that improvements in maternal mood may be necessary but not sufficient to improve additional dyadic and/or child developmental outcomes alone. In line with the mechanisms implicated in the intergenerational model of risk,Citation37 there may be multiple mediating and moderating factors implicated in the transmission of psychopathological risk from mother to infant.

The findings from this review have implications for the psychological treatment of PND and future research. While certain interventions have been shown to be effective for treating PND, the benefits for child development and the quality of the dyadic relationship are less clear, as evidenced by the discrepancy between effect sizes for improvements in maternal mood and dyad and developmental outcomes. Indeed, an improvement in maternal mood did not necessitate an improvement in developmental outcomesCitation35 as illustrated by the disparity in maternal, dyadic, and child outcomes reported in the present review. However, the incongruence between early outcomes may also be the result of a time delay between improvements in maternal mood and expectations from the infant resulting in the observed discrepancy. There may be a period of adjustment for the infant following improvements in maternal mood resulting in an observed dis-synchrony between the dyad.Citation33 In order to investigate this, long-term assessments of the mother–infant relationship are warranted.

The findings from the present review suggest that a developmental perspective into the conceptualization of how PND affects the mother and infant is needed. The role parents play in regulating their infants’ emotional states may be a key element in improving treatment efficacy and promoting long-term effectiveness.Citation89 There is a strong impetus for focusing on parenting skills and strategies as a medium for strengthening and protecting the mother–infant relationship, given the difficulties they experience with parenting. Despite significant reductions in depressive symptomatology, effect sizes were generally modest. While improvements to maternal mental health have been assessed, it remains important to also assess both short- and long-term benefits, to the mother’s ability to respond sensitively to her infant.

Quality of evidence

The impact of PND interventions on child development requires further research because it remains difficult to draw conclusions from the research or compare studies as a result of study limitations. A large proportion of the studies obtained inadequate scores on the CTAM. Many of the studies were characterized by small, biased sample sizes, which increases reporting of false-negative findings and the rejection of potentially effective treatments. Many also failed to describe the allocation and randomization process, thereby reducing methodological rigor. Furthermore, while most studies employed the use of blind assessors, the process of blinding was not described. Although the majority of the studies used an RCT design, many did not address drop-out appropriately (ie, only analyzing treatment completers). Fewer than half of the included studies described intervention protocol and/or methods to ensure treatment fidelity; this highlights a limitation regarding quality assurance. The methodological observations are comparable with the extant literature.Citation90,Citation91

The correlation between direction of effect size and strength of methodological quality is comparable to previous studies using the CTAM for assessment of trial methodological quality, which may be explained by the standard of reporting or length constraints of the journal in which they were published. One method for improving the quality of reporting RCTs is to implicate the use of Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, which outlines the gold standard for conducting RCTs. Alternately, as suggested by Cuijpers et alCitation70 quality assurance may be achieved by adherence to the Cochrane Handbook which outlines four criteria in ensuring quality assurance. Only four studies in this review presented Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials or participant flow diagrams.

There were also several observations with regard to participant characteristics, which warrant attention. Firstly, there was wide heterogeneity across study client inclusion criteria. Specifically, some studies included clients with a diagnosis of PND made by a professional, while others relied on screening measures alone, such as the EPDS. Although probable diagnosis is cost- and time-effective, there is a limitation that researchers who rely exclusively on screening questionnaires for eligibility are including participants who are experiencing comorbid diagnoses, which may invariably influence treatment efficacy. Secondly, we observed homogeneity in marital status, with a large proportion of women being in married/cohabiting relationships. Thirdly, there was a large degree of variability with regard to variables including age of the infant and severity and course of the depressive episode.

An additional observation is the impact that parity has on outcomes. For example, difficulties experienced may vary depending on whether mothers are primiparous or multiparous. Indeed, research has shown that primiparous and multiparous mothers experience different mother–infant relationship problems at 3 months postpartum.Citation92 This variance may be explained by differences between multiparous and primiparous mothers in adjustment to parenthood.Citation93

These methodological observations make it difficult to determine what to target in treatment, how long to do it for, and what delivery modality should be used. McLennan and OffordCitation35 have suggested that further research is needed to establish the role of PND as a risk factor to determine whether it should be targeted for improving developmental outcomes.

Recommendations for future research

Future research should include developmental and predictive measures of vulnerability toward future developmental psychopathology because these measures provide an index of long-term effectiveness.Citation94 There is also a need to acknowledge fathers when administering treatment.Citation19 According to the Goodman and Gotlib model,Citation37 fathers may moderate the transmission of risk.Citation95,Citation96 Since it is a period of adjustment, fathers face challenges in becoming new parents, including redefining their relationship and roles with their spouse and importantly learning to respond adaptively to their babies.Citation97 Research will need to consider the dyadic relationship and interactions between both parents and the developing infant. Risk factors (ie, sociodemographics) associated with PND as well as the concept of sensitive periods in development and resilience to adversity (infants are particularly vulnerable to PND, due in part to development of neuroregulatory mechanisms) need to be kept in mind.Citation22,Citation37

Research with clients from underrepresented groups with PND, including black and ethnic minority populations, is also needed. We found no studies which investigated effectiveness of interventions for PND in low-income or developing nations’ populations.

A further consideration for future research is the revisions to the diagnostic criteria which have altered the conceptualization of PND to include mood disorders with an onset in pregnancy. Sharma and MazmanianCitation98 highlighted that the inclusion of the prepartum and mixed feature specifiers would lead to increased awareness, monitoring, and appropriate timely treatment of women who are at risk of mood difficulties during their pregnancy, including mania, hypomania, and mixed episodes. However, they cautioned that the inclusion of the prepartum specifier may obscure etiological, clinical, and treatment differences between those with prepartum and postnatal onsets.

Limitations

The findings from this review are subject to some limitations. Firstly, strict search terms were used due to the volume of papers returned in initial searches. Hence, it is possible that some studies were excluded. Secondly, it was not possible to calculate effect sizes across all domains of assessment (maternal mood, mother–infant relationship, child developmental) due to missing data. Thirdly, there was a degree of variability regarding how a diagnosis of PND was established. For example, the inclusion of studies assessing participant eligibility through the use of screening measures (ie, the EPDS) and not formal diagnosis may have affected the reliability with which the results were interpreted.

Despite the evidence for the benefits, the review literature on the subject has highlighted that there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific treatment, and therefore, further research is warranted.Citation70,Citation74,Citation91

Conclusion

Maternal well-being and child development are inextricably linked. Our review has highlighted the poverty of interventions assessing outcomes relevant to both mother and infant. These findings highlight the need for further research to continue to measure the quality of the mother–infant relationship but also to add measurements of child development and long-term outcomes to their research programs. Further research addressing the highlighted methodological limitations is warranted. Until then, we can make no recommendation for any intervention in particular.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. ZLT conducted the systematic literature search and initial analysis. The first draft was prepared by ZLT and finalized by AW. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Nadine Santos for her assistance in preparing the revised manuscript.

Disclosure

No author has any share or ownership in Triple P International Pty Ltd. Matthew Sanders is the founder and an author of various Triple P programs and a consultant to Triple P International Pty Ltd. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MilgromJMartinPRNegriLMTreating Postnatal Depression: A Psychological Approach for Health Care PractitionersLondonWiley1999

- CooperPMurrayLThe impact of psychological treatments of postpartum depression on maternal mood and infant developmentMurrayLCPJPostpartum Depression and Child DevelopmentNew York, NYGuilford Press1997201220

- CoatesASchaeferCAlexanderJDetection of postpartum depression and anxiety in a large health planJ Behav Health Serv Res200431211713315255221

- BeckCTA meta-analysis of the relationship between postpartum depression and infant temperamentNurs Res19964542252308700656

- GialloRCooklinANicholsonJMRisk factors associated with trajectories of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the early parenting period: an Australian population-based longitudinal studyArch Womens Ment Health20141711512524424796

- WilliamsonVMcCutcheonHPostnatal depression: a review of current literatureAust J Midwifery2004174111615656151

- LeeDTSChungTHKPostnatal depression: an updateBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol200721218319117157072

- CooperPCampbellEADayAKennerleyHBondANon-psychotic psychiatric disorder after childbirth: a prospective study of prevalence, incidence, course and natureBr J Psychiatry19881527998063167466

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edWashtington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- BarnettBFowlerCCaring for the Family’s Future: A Practical Workbook on Recognising and Managing Post-Natal DepressionHaymarket, NSWNorman Swan Medical Communications1995

- PetrouSCooperPMurrayLDavidsonLLEconomic costs of postnatal depression in a high-risk British cohortBr J Psychiatry200218150551212456521

- Leahy-WarrenPMcCarthyGPostnatal depression: prevalence, mothers’ perspectives, and treatmentsArch Psychiatr Nurs20072129110017397691

- ReckCNoeDGerstenlauerJStehleEEffects of postpartum anxiety disorders and depression on maternal self-confidenceInfant Behav Dev201235226427222261433

- MoehlerEBrunnerRWiebelAReckCReschFMaternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bondingArch Womens Ment Health20069527327816937313

- ReckCNoeDStefenelliUInteractive coordination of currently depressed inpatient mothers and their infants during the postpartum periodInfant Ment Health J2011325542562

- FeldmanRGranatAParienteCKanetyHKuintJGilboa-SchechtmanEMaternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivityJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200948991992719625979

- HayDFPawlbySAngoldAHaroldGTSharpDPathways to violence in the children of mothers who were depressed postpartumDev Psychol20033961083109414584986

- MurrayLHalliganSLGoodyerIHerbertJDisturbances in early parenting of depressed mothers and cortisol secretion in offspring: a preliminary studyJ Affect Disord2010122321822319632727

- LetourneauNLDennisCLBenziesKPostpartum depression is a family affair: addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and childrenIssues Ment Health Nurs201233744545722757597

- BelskyJCongerRCpaldiDMThe intergenerational transmission of parentingDev Psychol2009451201120419702385

- ManningCGregoireAEffects of parental mental illness on childrenPsychiatr J2006511012

- MeaneyMJMaternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generationsAnnu Rev Neurosci2001241161119211520931

- DennisCLMcQueenKDoes maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes?Acta Paediatr200796459059417391475

- McLearnKTMinkovitzCSStrobinoDMMarksEHouWMaternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months postpartum and early parenting practicesArch Pediatr Adolesc Med200616027928416520447

- McLearnKTMinkovitzCSStrobinoDMMarksEHouWThe timing of maternal depressive symptoms and mothers’ parenting practices with your children: implications for pediatric practicePediatrics2006118e174e18216818531

- DennisCLRossLRelationships among infant sleep patterns, maternal fatigue, and development depressive symptomatologyBirth20053218719316128972

- HattonDCHarrison-HohnerJDoratoVCurenLBMcCarronDASymptoms of postpartum depression and breastfeedingJ Hum Lact20052144444916280561

- HiscockHWakeMInfant sleep problems and postnatal depression: a community-based studyPediatrics20011071317132211389250

- MinkovitzCSStrobinoDCharfsteinDHouWMillerTMistryKBMaternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of healthcare in the first 3 years of lifePediatrics200511530631415687437

- Zajicek-FarberMLPostnatal depression and infant health practices among high-risk womenJ Child Fam Stud2009182236245

- Zajicek-FarberMLThe contributions of parenting and postnatal depression on emergent language of children in low-income familiesJ Child Fam Stud2010193257269

- TronickEReckCInfants of depressed mothersHarv Rev Psychiatry200917214715619373622

- TronickEWeinbergMKDepressed mothers and infants: failure to form dyadic states of consciousnessMurrayLCooperPPostpartum Depression and Child DevelopmentNew York, NYGuilford Press19975481

- FormanDRO’HaraMWStuartSGormanLLLarsenKECoyKCEffective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationshipDev Psychopathol200719258560217459185

- McLennanJDOffordDRShould postpartum depression be targeted to improve child mental health?J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2002411283511800202

- O’HaraMWPostpartum depression: what we knowJ Clin Psychol200965121258126919827112

- GoodmanSHGotlibIHRisk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmissionPsychol Rev1999106345849010467895

- MurrayLArtecheAFearonPHalliganSCroudaceTCooperPThe effects of maternal postnatal depression and child sex on academic performance at age 16 years: a developmental approachJ Child Psychol Psychiatry2010511011501159 Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t20840504

- MurrayLCooperPEffects of postnatal depression on infant developmentArch Dis Child1997772991019301345

- MurrayLCooperPThe role of infant and maternal factors in postpartum depression, mother-infant interactions, and infant outcomeMurrayLCPJPostpartum Depression and Child DevelopmentNew York, NYGuilford Press1997111135

- GraceSLEvindarAStewartDEThe effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literatureArch Womens Ment Health20036426327414628179

- CohnJFCampbellSBMatiasRHopkinsJFace-to-face interactions of postpartum depressed and nondepressed mother-infant pairs at 2 monthsDev Psychol19902611523

- MurrayLArtecheAFearonPHalliganSGoodyerICooperPMaternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of ageJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201150546047021515195

- MilgromJWestleyDGemmillAThe mediating role of maternal responsiveness in some longer term effects of postnatal depression on infant developmentInfant Behav Dev2004274443454

- KingstonDToughSWhitfieldHPrenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic reviewChild Psychiatry Hum Dev20124368371422407278

- KingstonDToughSPrenatal and postnatal maternal mental health and school-age child development: a systematic reviewMatern Child Health J2014181728174124352625

- ThompsonRAEarly sociopersonality developmentDamonWEisenbergNHandbook of Clinical Psychology3New YorkWiley199825104

- SteinACraskeMGLehtonenAMaternal cognitions and mother-infant interaction in postnatal depression and generalized anxiety disorderJ Abnorm Psychol2012121479580922288906

- CrittendenPMRaising Parents: Attachment, Parenting and Child SafetyDevonWillan2008

- GerhardtSWhy love matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s BrainNew YorkRoutledge/Taylor and Francis Group2004

- HayDFPostpartum depression and cognitive developmentMurrayLCooperPJPostpartum Depression and Child DevelopmentNew YorkGuilford Press199785110

- MoutsianaCFearonPMurrayLMaking an effort to feel positive: insecure attachment in infancy predicts the neural underpinnings of emotion regulation in adulthoodJ Child Psychol Psychiatry2014559999100824397574

- ArtecheAJoormanJHarveyAThe effects of postnatal maternal depression and anxiety on the processing of infant facesJ Affect Disord201113319720321641652

- Van Den BoomDCThe influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: an experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infantsChild Dev1994655145714777982362

- LogsdonMWisnerKHanusaBHDoes maternal role functioning improve with antidepressant treatment in women with postpartum depression?J Womens Health20091818590

- PearlsteinTBZlotnickCBattleCLPatient choice of treatment for postpartum depression: a pilot studyArch Womens Ment Health20069630330816932988

- AustinMPFrilingosMLumleyJBrief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trialJ Affect Disord20081051–3354417490753

- RojasGFritschRSolisJTreatment of postnatal depression in low-income mothers in primary-care clinics in Santiago, Chile: a randomised controlled trialLancet200737095991629163717993363

- UgarrizaDNGroup therapy and its barriers for women suffering from postpartum depressionArch Psychiatr Nurs2004182394815106134

- MilgromJEricksenJMcCarthyRGemmillAWStressful impact of depression on early mother-infant relationsStress Health2006224229238

- MurrayLCooperPJWilsonARomaniukHControlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression 2. Impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcomeBr J Psychiatry200318242042712724245

- MulcahyRReayREWilkinsonRBOwenCA randomised control trial for the effectiveness of group interpersonal psychotherapy for postnatal depressionArch Womens Ment Health201013212513919697094

- ReayRFisherYRobertsonMAdamsEOwenCGroup interpersonal psychotherapy for postnatal depression: a pilot studyArch Womens Ment Health200691313916222425

- Van DoesumKRiksen-WalravenJHosmanCHoefnagelsCA randomized controlled trial of a home-visiting intervention aimed at preventing relationship problems in depressed mothers and their infantsChild Dev200879354756118489412

- ClarkRTluczekABrownRA mother-infant therapy group model for postpartum depressionInfant Ment Health J2008295514536

- JungVShortRLetourneauNAndrewsDInterventions with depressed mothers and their infants: modifying interactive behavioursJ Affect Disord200798319920516962666

- O’HigginsMRobertsISGloverVPostnatal depression and mother and infant outcomes after infant massageJ Affect Disord20081091–218919218086500

- OnozawaKGloverVAdamsDModiNKumarRCInfant massage improves mother-infant interaction for mothers with postnatal depressionJ Affect Disord2001631–320120711246096

- NylenKJMoranTEFranklinCLO’HaraMWMaternal depression: a review of relevant treatment approaches for mothers and infantsInfant Ment Health J2006274327343

- CuijpersPBrannmarkJGVan StratenAPsychological treatment of postpartum depression: a meta-analysisJ Clin Psychol200864110311818161036

- TandonSDPerryDFMendelsonTKempKLeisJAPreventing perinatal depression in low-income home visiting clients: a randomized controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol201179570771221806298

- MorrellCJReview of interventions to prevent or treat postnatal depressionClin Eff Nurs200692e135e161

- ClaridgeAMEfficacy of systematically oriemted psychotherapies in the treatment of perinatal depression: a meta-analysisArch Womens Ment Health20141731524240636

- PoobalanASAucottLSRossLSmithWCSHelmsPJWilliamsJHGEffects of treating postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction and child development: systematic reviewBr J Psychiatry2007191437838617978316

- TarrierNWykesTIs there evidence that cognitive behaviour therapy is an effective treatment for schizophrenia? A cautious or cautionary tale?Behav Res Ther200442121377140115500811

- JadadARMooreRACarrollDAssessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?Control Clin Trials19961711128721797

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2 edHillsdaleLawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc1988

- ClarkRTluczekAWenzelAPsychotherapy for postpartum depression: a preliminary reportAm J Orthopsychiatry200373444145414609406

- FieldTGrizzleNScafidiFMassage therapy for infants of depressed mothersInfant Behav Dev1996191107112

- HorowitzJABellMTrybulskiJPromoting responsiveness between mothers with depressive symptoms and their infantsJ Nurs Scholarsh200133432332911775301

- Kersten-AlvarezLEHosmanCMHRiksen-WalravenJMVan DoesumKTMHoefnagelsCLong-term effects of a home-visiting intervention for depressed mothers and their infantsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry201051101160117020707826

- CooperPMurrayLWilsonARomaniukHControlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. 1. Impact on maternal moodBr J Psychiatry2003182541241912724244

- BeeberLSSchwartzTAHolditch-DavisDCanusoRLewisVWilde HallHParenting enhancement interpersonal psychotherapy to reduce depression in low-income mothers of infants and toddlers: a randomised trialNurs Res201362829023458906

- HorowitzJAMurphyCAGregoryKWojcikJPulciniJSolonLNurse home visits improve maternal/infant interaction and decrease severity of postpartum depressionJ Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs201342287300

- GoodmanJHPragerJGoldsteinRFreemanMPerinatal dyadic psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a randomised controlled pilot trialArch Womens Ment Health2014

- TsivosZLCalamRSandersMRWittkowskiAA pilot randomised controlled trial to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the baby triple P positive parenting programme in mothers with postnatal depressionClin Child Psychol Psychiatry2014123

- ClarkRThe Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment [Unpublished instrument] Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin1985

- RichmanNGrahamPA behavioural screening questionnaire for use with three-year old children, preliminary findingsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry197112153323289166

- GoodmanSHBrothMRHallCMStoweZNTreatment of postpartum depression in mothers: secondary benefits to the infantsInfant Ment Health J2008295492513

- BoathEHHenshawCThe treatment of postnatal depression: a comprehensive literature reviewJ Reprod Infant Psychol2001193215248

- DennisCLCan we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale?J Affect Disord200478216316914706728

- Righetti-VeltemaMConne-PerreardEBousquetAManzanoJPostpartum depression and mother-infant relationship at 3 months oldJ Affect Disord200270329130612128241

- GameiroSMoura-RamosMCanavarroMCMaternal adjustment to the birth of a child: primiparity versus multiparityJ Reprod Infant Psychol2009273269286

- CarterASBriggs-GowanMJJonesSMLittleTDThe infant-toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validityJ Abnorm Child Psychol200331549551414561058

- GoodmanJHPaternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family healthJ Adv Nurs2004451263514675298

- PaulsonJBazemoreSPrenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysisJAMA2010303191961196920483973

- KowlessarOFoxJREWittkowskiAThe pregnant male: a metasynthesis of fathers’ experiences of pregnancyJ Reprod Infant Psychol2015332106127

- SharmaVMazmanianDThe DSM-5 peripartum specifier: prospects and pitfallsArch Womens Ment Health20141717117324414301