Abstract

Background

The role of arterial stiffness in the pathophysiology of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is unclear. The cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) is a novel arterial stiffness index reflecting stiffness of the arterial tree from the origin of the aorta to the ankle, independent from blood pressure at the time of measurement. CAVI reflects functional stiffness, due to smooth muscle cell contraction or relaxation, and organic stiffness, due to atherosclerosis. Here, we report the case of a patient with an increased CAVI due to CTEPH and the improvement after riociguat administration and balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA).

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man suffered from dyspnea on exertion, and he was diagnosed with distal CTEPH. The mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) was 51 mmHg, and the initial CAVI was 10.0, which is high for patient’s age. In addition to right ventricular dysfunction, left ventricular dysfunction was observed as reduced global longitudinal strain (GLS-LV). After riociguat administration, CAVI decreased to 9.1 and GLS-LV improved from −10.3% to −17.3%, although pulmonary hypertension remained (mPAP 41 mmHg). Subsequently, a total of five BPA sessions were performed. Six months after the final BPA, mPAP decreased to 19 mmHg and GLS-LV improved to 19.3%. The patient was symptom free and his 6-minute walk distance improved from 322 m to 510 m. CAVI markedly decreased to 5.8, which is extremely low for his age.

Conclusion

These observations suggested that arterial stiffness as measured by CAVI was increased in CTEPH, potentially deteriorating cardiac function because of enhanced afterload. The mechanism of the increase of CAVI in this case of CTEPH was obscure; however, riociguat administration and BPA might improve the pathophysiology of CTEPH partly by decreasing CAVI.

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is an intractable disease caused by organized thrombi in the pulmonary arteries, and its prognosis is extremely poor without treatment.Citation1 The predominant cause of pulmonary artery obstruction in CTEPH is organized thrombi in the large pulmonary arteries. It has also been suggested that small vessel remodeling of the pulmonary muscular arteries can be involved in the pathophysiology of CTEPH; however, the precise mechanism remains unclear.Citation2

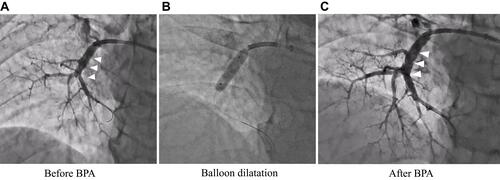

Involvement of arterial stiffness in the pathophysiology of CTEPH has been suggested using pulse wave velocity (PWV) as an index of arterial stiffness.Citation3 However, the PWV is dependent on blood pressure (BP) at the time of measurement.Citation4,Citation5 Therefore, investigation of the role of arterial stiffness in the pathophysiology of CTEPH has been complicated. Recently, the cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) was developed as a novel arterial stiffness index, which has several unique features, including 1) independence from BP at the time of measurement, 2) measurement of arterial stiffness from the aortic root to the ankle, and 3) reflection of both organic stiffness, due to atherosclerosis, and functional stiffness, due to vascular smooth muscle cell contraction or relaxation.Citation6,Citation7 The role of CAVI as a surrogate marker of atherosclerosis has been established.Citation8 Moreover, CAVI may also be useful as a circulation parameter of the systemic circulation, especially as an indicator of left ventricle (LV) afterload.Citation9 Recently, Radchenko et al reported that arterial stiffness evaluated by CAVI was significantly higher in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) than in healthy subjects.Citation10 These findings suggest that increased arterial stiffness may increase afterload of LV and may affect cardiac function in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) including CTEPH. Therefore, arterial stiffness may play an important role in the pathophysiology of CTEPH. Here, we report the case of a patient with CTEPH with an elevated CAVI who had recovered from hemodynamically abnormal conditions. The CAVI showed marked improvement after treatment with riociguat and subsequent balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) (–). We present the changes in CAVI during those treatments for CTEPH and discuss their meaning.

Case Presentation

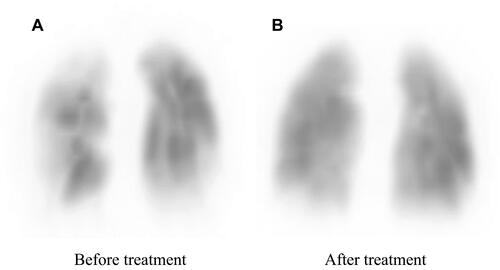

A 65-year old man with a two-year history of dyspnea on exertion was referred to our hospital. He had a history of hypertension and used conventional prescription drugs. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed severe PH, and lung perfusion scintigraphy showed multiple segmental perfusion defects, which are consistent with CTEPH (). There was no coagulopathy evident from blood tests. After 3 months of anticoagulant therapy with warfarin, we performed right heart catheterization. The mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) was 51 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was 13.6 wood units (). Cardiac output (CO) was decreased (CO 3.32 L/min, cardiac index 1.82 L/min/m2), whereas pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was in the normal range (). Pulmonary angiography showed organized thrombi in the segmental or subsegmental pulmonary arteries (). These findings were consistent with distal type CTEPH.

Table 1 Changes in Clinical Parameters from Diagnosis of CTEPH Until 12 Months

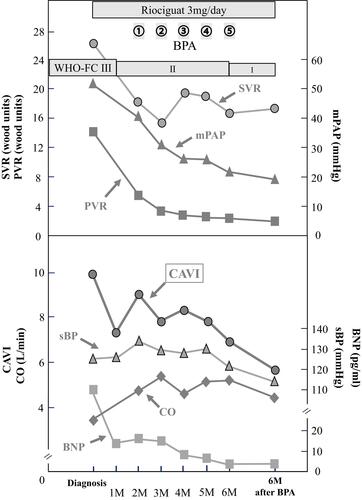

Figure 3 Clinical course of the patient and changes in various circulation parameters and CAVI.

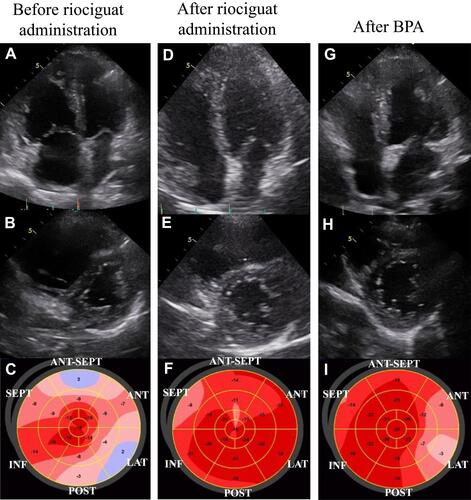

At the time of the CTEPH diagnosis, the CAVI was 10.0, indicating arterial stiffness. This value was high for his age since the normal CAVI value in healthy Japanese males in their sixties is 8.63±0.81.Citation11 Although his BP was in the normal range, systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was enhanced (). Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction due to severe PH was detected as enlargement of the right ventricle (RV) and reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), which was 14.3 mm by TEE (). Moreover, the enlarged RV compressed the interventricular septum, which was shifted leftward ( and ). Although his LV ejection fraction was within the normal range, LV diastolic dysfunction was detected (e’ 2.3 cm/sec and E/e’ 16.5, ). It is possible that both the shifted septum and the enhanced CAVI may cause LV dysfunction. In addition, global longitudinal strain on the left ventricle (GLS-LV) was examined to further investigate the LV function.Citation12 GLS-LV at diagnosis of CTEPH was 10.3%, indicating that LV dysfunction and the impairment of longitudinal strain (LS) was observed in both septal and non-septal LV segments ().

Table 2 Changes in Echocardiographic Findings

Figure 4 Changes in echocardiographic findings during treatment. Apical 4-chamber view, short axis view and bull’s-eye showing segments of the left ventricle to determine GLS are shown in order. Before riociguat administration (A–C), after riociguat administration (D–F) and after BPA (G–I).

According to angiographic findings, there were many surgically inaccessible lesions. Therefore, we decided to perform BPA. Administration of riociguat, a soluble guanyl acid cyclase (sGC) stimulator that leads to increased cGMP generation with subsequent vasodilation, was started to decrease mPAP as far as possible before the BPA. Subsequently, symptoms improved from the World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) III to II, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level was normalized (). After riociguat administration, mPAP and PVR decreased, and CO increased (mPAP 51 mmHg to 41 mmHg, PVR 13.6 wood units to 5.5 wood units, CO 3.3 L/min to 4.8 L/min, ). The CAVI also improved from 10.0 to 9.1 after riociguat administration, along with the reduction of SVR (26.2 wood units to 18.2 wood units), but BP did not decrease (). TTE also indicated that GLS-LV improved to 17.2%, and the compression of the LV was released, but PH and RV enlargement still existed (–).

Finally, a total of five BPA sessions were performed with no complications. Before the final session, mPAP had decreased to 21 mmHg, and CAVI decreased gradually. Six months after the final BPA, mPAP was 19 mmHg, which was within the normal range (). Lung perfusion defects detected by scintigraphy had improved markedly (). Symptoms improved to WHO-FC class I, and the 6-minute walk distance improved from 322 m to 510 m (). Moreover, CAVI decreased to 5.8, which was extremely low for his age (). Enlargement of the RV and TAPSE were improved after treatment, and GLS-LV remained within the normal range (– and ).

At the CTEPH diagnosis, the patient had angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for hypertension, however, ARB was discontinued due to hypotension after riociguat administration. Before treatment, his lipid profile was with in the normal range [total cholesterol 185 mg/dl, triglyceride 124 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 43 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) 123mg/dl]. Although LDL-C level slightly decreased to 111 mg/dl after treatment, any drugs which could affect CAVI value such as statin, were not added during treatment period.

Discussion

The main findings concerning arterial stiffness in this case were: 1) initial CAVI value before treatment was relatively high for his age, 2) both riociguat administration and subsequent BPA decreased the CAVI value along with improvement of hemodynamics, and 3) CAVI value had remained extremely low up to 6 months after the final BPA session.

The initial CAVI in the presented case was 10.0, which suggested that organized atherosclerosis was advanced in this case of CTEPH. However, CAVI improved within one month after riociguat administration. It is difficult to imagine that one month was enough time for atherosclerosis to regress to the point of decreasing the CAVI. Furthermore, CAVI decreased following monthly BPA. These results strongly suggested that CAVI was initially increased due to vascular smooth muscle cell contraction in CTEPH. This enhancement of functional stiffness may probably be explained by sympathetic nerve activation, arising from reduced cardiac output due to severe PH and increased physical and/or mental stress caused by severe dyspnea and hypoxia.Citation13,Citation14 Thus, the functional stiffness could be enhanced in right heart failure patients including CTEPH which are prone to hypotension due to their low cardiac output state. Importantly, the functional stiffness enhancement could be evaluated by CAVI.

On the other hand, enhanced arterial stiffness is thought to result in high afterload on the LV, which can deteriorate LV function. Recently, Kishiki et al reported that patients with PAH had LV dysfunction, detected as reduced GLS-LV and LV diastolic dysfunction, in addition to right heart dysfunction, and the LV dysfunction was strongly associated with mortality.Citation15 They also reported that the LS was impaired in both septal and non-septal LV segments. This result suggests that the LV dysfunction was caused not only by interventricular effect due to RV pressure and/or volume overload but also by other factors that affect the LV function in patients with PAH. In this case of CTEPH, impairment of the LS was also detected in both septal and non-septal segments of the LV segments before treatment (). After riociguat administration, mPAP and PVR were decreased, but PH and RV enlargement persisted, whereas the CAVI and SVR decreased and CO increased (, and ). In addition, GLS-LV was markedly improved (). Additionally, Namba et al reported that high CAVI values were independently associated with LV diastolic dysfunction.Citation16 In this patient, enhanced CAVI may have affected his LV diastolic function, which may impair GLS-LV.

Riociguat has a strong vasodilating effect through the stimulation of sGC and subsequent increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate. But it was reported that improvement of PH in patients with inoperable CTEPH by riociguat was limited; the mean reduction of mPAP was −4±7 mmHg in the CHEST-1 trial.Citation17 The vasodilating effect of riociguat may thus work on the systemic circulation in these patients. Similarly, in the present case, it is possible that riociguat predominantly dilated systemic peripheral arteries and reduced afterload on the LV, resulting in improved cardiac function and pulmonary circulation. In spite of the strong vasodilating effect of riociguat, the reason why BP did not decrease after riociguat administration, in this case, was that the improvement of CO might have offset a decrease of BP due to the vasodilating effect on systemic arteries.

BPA is a new promising therapeutic strategy for patients with inoperable and distal-type CTEPH. BPA has been developed in the last decade, and CTEPH has become a curative disease even in inoperable patients.Citation18,Citation19 In principle, BPA directly improves pulmonary circulation but does not directly affect systemic arterial stiffness. However, in this case, CAVI was further decreased by additional BPA. Although the effect of riociguat administration might explain this decline of CAVI, BPA may have an additional effect on systemic arterial stiffness by improving the pulmonary circulation. It is possible that this improved pulmonary circulation caused the improvement of the systemic circulation, providing good oxygenation and sympathetic nerve deactivation by relief of the stress. Tatebe et al reported that CAVI improved after BPA, along with hemodynamic improvement and improvement of various systemic disorders in CTEPH patients.Citation20 Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, CAVI may be indirectly improved as a result of the improvement of various systemic disorders in addition to hemodynamic stabilization. This case report is novel in that, both riociguat and BPA improved CAVI, and discussed the relationship between CAVI and cardiac function especially LV function evaluated by GLS-LV.

In the current case, the improvement of CAVI was maintained over six months by riociguat and BPA, along with improvement in conventional hemodynamic parameters such as mPAP, PVR, CO, and SVR. These results suggest that systemic arterial stiffness may be involved in the pathophysiological mechanism of CTEPH. Enhanced arterial stiffness evaluated by CAVI may provide new insight into these mechanisms. As shown in this case, serial assessment of arterial stiffness by CAVI may be a useful afterload indicator that has different unique features from conventional afterload indicators, such as blood pressure and vascular resistance. In addition, both riociguat and BPA were effective in relieving arterial stiffness. In patients with CTEPH, increased arterial stiffness may affect cardiac function as a result of increased afterload. Evaluating arterial stiffness using CAVI, the pathophysiologic condition could be understood in more detail, which may lead to appropriate treatment selection for CTEPH patients. In addition, observing the changes in CAVI may be a useful index to evaluate the therapeutic effect of riociguat and/or BPA non-invasively. This report highlights that further studies are required to clarify the precise mechanisms of this disease.

Ethical Approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and national committees on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, and subsequent revisions). According to the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Toho University School of Medicine (September 18, 2018), institutional approval was not required to publish the case details.

Informed Consent

The patient provided written informed consent for publication of the details of his case and the images shown in the figure.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the cardiology, rehabilitation, and clinical functional physiology staff at Toho University Sakura Medical Center.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Riedel M, Stanek V, Widimsky J, Prerovsky I. Long term follow-up of patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. Late prognosis and evolution of hemodynamic and respiratory data. Chest. 1982;81(2):151–158. doi:10.1378/chest.81.2.151

- Jujo T, Sakao S, Ishibashi-Ueda H, et al. Evaluation of the microcirculation in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension patients: the impact of pulmonary arterial remodeling on postoperative and follow-up pulmonary arterial pressure and vascular resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133167

- Sznajder M, Dzikowska-Diduch O, Kurnicka K, et al. Increased systemic arterial stiffness in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiol J. 2018;7:e009459.

- Cecelja M, Chowienczyk P. Dissociation of aortic pulse wave velocity with risk factors for cardiovascular disease other than hypertension: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2009;54(6):1328–1336. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137653

- Schillaci G, Battista F, Settimi L, Anastasio F, Pucci G. Cardio-ankle vascular index and subclinical heart disease. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(1):68–73. doi:10.1038/hr.2014.138

- Shirai K, Song M, Suzuki J, et al. Contradictory effects of β1- and α1-adrenergic receptor blockers on cardio-ankle vascular stiffness index (CAVI): CAVI is independent of blood pressure. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:49–55. doi:10.5551/jat.3582

- Shimizu K, Yamamoto T, Takahashi M, Sato S, Noike H, Shirai K. Effect of nitroglycerin administration on cardio-ankle vascular index. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:313–319. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S106542

- Shirai K, Saiki A, Nagayama D, Tatsuno I, Shimizu K, Takahashi M. The role of monitoring arterial stiffness with cardio-ankle vascular index in the control of lifestyle-related diseases. Pulse. 2015;3(2):118–133. doi:10.1159/000431235

- Sato S, Takahashi M, Mikamo H, et al. Effect of nicorandil administration on cardiac burden and cardio-ankle vascular index after coronary intervention. Heart Vessels. 2020;35:1664–1671. doi:10.1007/s00380-020-01650-9

- Radchenko GD, Zhyvylo IO, Titov EY, Sirenko YM. Systemic arterial stiffness in new diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2020;16:29–39. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S230041

- Otsuka K, Fukuda S, Shimada K, et al. Serial assessment of arterial stiffness by cardio-ankle vascular index for prediction of future cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Hypertens Res. 2014;37(11):1014–1020. doi:10.1038/hr.2014.116

- Potter E, Marwick TH. Assessment of left ventricular function by echocardiography: the case for routinely adding global longitudinal strain to ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(2):260–274. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.11.017

- Ciarka A, Doan V, Velez-Roa S, et al. Prognostic significance of sympathetic nervous system activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(11):1269–1275. doi:10.1164/rccm.200912-1856OC

- Velez-Roa S, Ciarka A, Najem B, Vachiery JL, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Increased sympathetic nerve activity in pulmonary artery hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:1308–1312. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000140724.90898.D3

- Kishiki K, Singh A, Narang A, et al. Impact of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension on the left heart and prognostic implications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(9):1128–1137. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2019.05.008

- Namba T, Masaki N, Matsuo Y, et al. Arterial stiffness is significantly associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease. Int Heart J. 2016;5:729–735. doi:10.1536/ihj.16-112

- Ghofrani HA, D’Armini AM, Grimminger F, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:319–329. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209657

- Sugimura K, Fukumoto Y, Satoh K, et al. Percutaneous transluminal pulmonary angioplasty markedly improves pulmonary hemodynamics and long-term prognosis in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2012;76(2):485–488. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1217

- Ikeda N. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2020;35(2):130–141. doi:10.1007/s12928-019-00637-2

- Tatebe S, Sugimura K, Aoki T, et al. Multiple beneficial effects of balloon pulmonary angioplasty in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2016;80(4):980–988. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-15-1212