Abstract

This is the first reported case of an enterocutaneous fistula as a late complication to reconstruction of the pelvic floor with a Permacol™ mesh after a perineal hernia. A 70-year-old man had a reconstruction of the pelvic floor with a biological mesh because of a perineal hernia after laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection. Nine months after the perineal hernia operation, the patient had multiple metastases in both lungs and liver. The patient underwent chemotherapy, including bevacizumab, irinotecan, calcium folinate, and fluorouracil. Six weeks into chemotherapy, the patient developed signs of sepsis and complained of pain from the right buttock. Ultrasound examination revealed an abscess, which was drained, guided by ultrasound. A computed tomography scan showed a subcutaneous abscess cavity located in the right buttock with communication to the small bowel. Operative findings confirmed a perineal fistula from the distal ileum to perineum. A resection of the small bowel with primary anastomosis was performed. The postoperative course was complicated by fluid and electrolyte disturbances, but the patient was stabilized and finally discharged to a hospice for terminal care after 28 days of hospital stay. It seems that hernia repairs with biological meshes have lower erosion and infection rates compared with synthetic meshes, and so far, evidence suggests that biological grafts are safe and effective in the treatment of pelvic floor reconstruction. There have been no reports of enteric fistulas after pelvic reconstruction with biological meshes. However, the development of intestinal fistulas after chemotherapy with bevacizumab has been described in the literature. Our case report supports this association between bevacizumab and fistula formation among rectal cancer patients, as symptoms of a fistula started only 6 weeks into bevacizumab treatment but approximately 12 months after the perineal hernia operation, even after pelvic reconstruction using a biological mesh and without local recurrence.

Introduction

Postoperative perineal hernia occurs after conventional abdominoperineal resection (APR) and after the extralevator technique of APR (extralevator abdominoperineal excision; ELAPE) or pelvic exenteration. It has traditionally been reported to have a low incidence, ranging from 0.6% to 7%.Citation1 Various techniques, including primary suture, muscular flaps, and synthetic or biological meshes, have been used to repair the defect in the pelvic floor. Biological meshes are currently used in perineal reconstruction after ELAPE, but the literature on biologics in pelvic floor surgery is limited to case series/reports, with limited follow-up and lack of randomized trials.Citation2,Citation3 Only a few complications have been reported to date, such as seroma and perineal pain. To our knowledge, we present the first case of an enterocutaneous fistula as a late complication to reconstruction of the pelvic floor with a Permacol™ mesh (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) after perineal hernia.

Case report

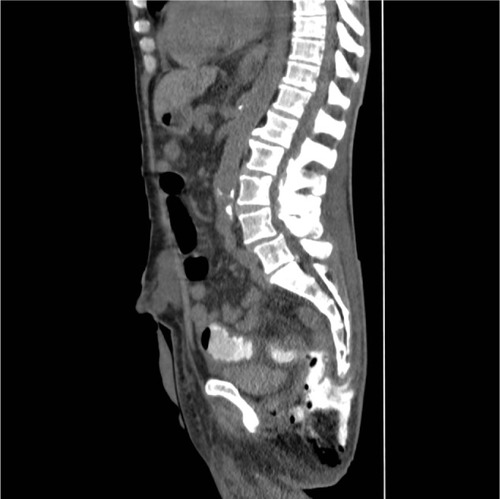

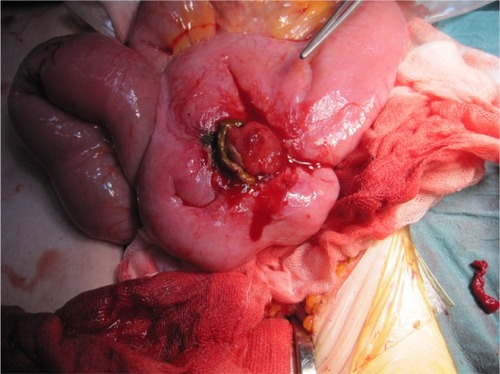

A 70-year-old man with a T3V1N0M0 rectal tumor underwent laparoscopic APR followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and calcium folinate. At 1 year control, radiological work-up and colonoscopy showed no signs of recurrence or distant metastases. Thirteen months after the APR, the patient developed a perineal hernia and had a reconstruction of the pelvic floor with a biological mesh (Permacol™) via a transperineal approach. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the initial follow-up with a pelvic–abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan 4 months after the surgery showed no signs of locoregional recurrence or reherniation. Nine months after the perineal hernia operation, the patient experienced weight loss. A thoracic–abdominal CT scan was performed and showed multiple metastases to the liver and lungs. The patient was treated with chemotherapy: bevacizumab, irinotecan, calcium folinate, and fluorouracil. Twelve months after the perineal hernia operation, but only 6 weeks into chemotherapy, the patient developed signs of sepsis with a high temperature, tachycardia, and hypotension and complained of pain in the right buttock. Physical examination showed signs of infection at the area. Possible differential diagnoses could have been local recurrence of the rectal cancer, intraabdominal abscess, or pelvis sepsis. We could have chosen to examine the patient with a positron emission tomography scan or, for example, an ultrasound (US)-guided biopsy, but we chose an acute US examination. This revealed an abscess, and drainage was established by a US-guided procedure. The patient was moved to an intensive unit and started treatment with intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. The following CT scan with contrast given through the drain showed a subcutaneous abscess cavity located in the perineum, with communication to the small bowel (). The patient underwent a laparotomy, and operative findings confirmed a perineal fistula from the distal ileum (). A resection of the small bowel with primary anastomosis was performed. The postoperative course was complicated by severe fluid and electrolyte disturbances. The patient was in the intensive care unit for a total of 16 days before treatment with pressors, intravenous fluids, and parenteral nutrition stabilized the patient. The perineal wound was treated with vacuum-assisted closure for a total of 20 days. There were no complications in the closure treatment. According to the patient’s request, he was discharged to hospice for terminal care after 28 days of hospital stay.

Discussion

Synthetic meshes have been used in the repair of perineal hernias, but they have limitations in potentially contaminated or infected fields, with risk for fistula formation, chronic inflammation, stiffness, erosion, small bowel adhesions, and chronic mesh infections.Citation1,Citation2

Bülow et al reported that intraoperative perforation is a significant risk factor for local and distant recurrence and survival in rectal cancer patients, and therefore should be avoided.Citation4 In such a setting, the potential risk for erosion, and thereby perforation of the bowel, makes the use of synthetic mesh adverse in rectal cancer surgery.Citation4 Biological meshes use the collagen network of human, porcine, or bovine tissues instead of synthetic materials, and they have theoretical advantages compared with synthetic meshes, such as superior incorporation and less risk of infection.Citation1,Citation2 More recently, they have been used to close the perineum after ELAPE and in the treatment of perineal hernias.Citation3 There is now considerable literature to support the use of biologic meshes.Citation1–Citation3 Hübner et al reviewed the use of flap reconstruction against reconstruction with a biological mesh after ELAPE. Perineal wound complications occurred in 28% of the participants and 3.5% developed a perineal hernia after reconstruction with a biological mesh compared with 32% and 3.9% after flap reconstruction, respectively.Citation2 In our case, we used Permacol™ (Tissue Science Laboratories/Covidien plc, Dublin, Ireland), which is a natural acellular biological collagen that is gradually absorbed and replaced by the patient’s own collagen. There have been no reports of enteric fistulas after pelvic reconstruction with biological meshes. Ahmed et al recently reviewed pelvic floor reconstruction with either a synthetic or a biological mesh. They found 4% mesh erosion with nonabsorbable synthetic mesh repair in sacrocolpopexy, compared with 0% with biological graft repair. These lower erosion rates are reproduced in the repair of transvaginal rectocele, where using Permacol™ had 0% erosion compared with 7% erosion with synthetic mesh. Ahmad et alCitation3 also report lower infection rates using Permacol™ (0%) versus synthetic mesh (13%) in transperineal rectocele repair.Citation3

Although we used Permacol™ for pelvic reconstruction in our patient, other factors may have played a role in the enteric fistula formation. For example, chemotherapy against metastatic disease, and especially bevacizumab, is suspected to cause enteric fistulas. The incidence of gastrointestinal perforations in colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab has been reported, ranging from 0.9 to 2.0.Citation5 The relative risk of gastrointestinal perforation in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with bevacizumab has been reported to be between 3.68 and 5.04.Citation5 The majority of the gastrointestinal perforations occurred within the first 6 months of treatment with bevacizumab. Ganapathi et al investigated the correlation between bevacizumab treatment and fistula formation after resection of advanced colorectal cancer.Citation6 A total of nine patients (4.1%), who had undergone surgical excision for colorectal cancer and subsequently received bevacizumab, developed enteric fistulas. It was pointed out that the development of fistulas was probably secondary to bevacizumab therapy, rather than a surgical complication. The average time elapsed from the initial operation to the initiation of bevacizumab was 23.6 (range, 9–42) months. The average time before developing a complication after treatment with bevacizumab was 3.9 (range, 1–9) months. In our case, reported symptoms of the fistula started 6 weeks into bevacizumab treatment and approximately 12 months after the perineal hernia operation. Thus, it seems most likely that the complication was a result of the bevacizumab treatment, rather than a complication to the perineal hernia repair with a Permacol™ mesh. There is no evidence that a late fistula caused by erosion or chemotherapy alters oncological outcome.

In conclusion, it seems that hernia repairs with biological meshes have lower erosion and infection rates compared with synthetic meshes, and so far, evidence suggests that biological grafts are safe and effective in the treatment of pelvic floor reconstruction. However, our case report supports the literature about the association between bevacizumab and fistula formation among rectal cancer patients, even after pelvic reconstruction using a biological mesh and without local recurrence.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MartijnseISHolmanFNieuwenhuijzenGARuttenHJNienhuijsSWPerineal hernia repair after abdominoperineal rectal excisionDis Colon Rectum2012551909522156873

- HübnerMStreitDHahnloserDBiological materials in colorectal surgery: current applications and potential for the futureColorectal Dis201214Suppl 3343923136823

- AhmadMSileriPFranceschilliLMercer-JonesMThe role of biologics in pelvic floor surgeryColorectal Dis201214Suppl 3192323136820

- BülowSChristensenIJIversenLHHarlingHDanish Colorectal Cancer GroupIntra-operative perforation is an important predictor of local recurrence and impaired survival after abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancerColorectal Dis201113111256126420958912

- HapaniSChuDWuSRisk of gastrointestinal perforation in patients with cancer treated with bevacizumab: a meta-analysisLancet Oncol200910655956819482548

- GanapathiAMWestmorelandTTylerDMantyhCRBevacizumab-associated fistula formation in postoperative colorectal cancer patientsJ Am Coll Surg2012214458258822321523