Abstract

It is reported that 6% of children and 3% of adults have food allergies, with studies suggesting increased prevalence worldwide over the last few decades. Despite this, our diagnostic capabilities and techniques for managing patients with food allergies remain limited. We have conducted a systematic review of literature published within the last 5 years on the diagnosis and management of food allergies. While the gold standard for diagnosis remains the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge, this assessment is resource intensive and impractical in most clinical situations. In an effort to reduce the need for the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge, several risk-stratifying tests are employed, namely skin prick testing, measurement of serum-specific immunoglobulin E levels, component testing, and open food challenges. Management of food allergies typically involves allergen avoidance and carrying an epinephrine autoinjector. Clinical research trials of oral immunotherapy for some foods, including peanut, milk, egg, and peach, are under way. While oral immunotherapy is promising, its readiness for clinical application is controversial. In this review, we assess the latest studies published on the above diagnostic and management modalities, as well as novel strategies in the diagnosis and management of food allergy.

Introduction

European studies estimate the lifetime prevalence of food allergy is 17.3% and the point prevalence 6%.Citation1 Recent studies suggest an increased prevalence worldwide over the last few decades of food allergy and food-induced anaphylaxis.Citation2,Citation3 Despite the increasing prevalence of food allergy, our diagnostic and management strategies have remained relatively unchanged over time. The double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of food allergies, but is rarely employed by physicians outside of an academic context. It is estimated that DBPCFCs have a false negative rate ranging from 2%–5% and a false positive rate near 5.4%–12.9%.Citation4 The open food challenge (OFC) is a more viable option for most clinicians, though it is not without its own pitfalls.

Most clinicians rely on skin prick testing (SPT) and serum-specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) testing to establish the diagnosis of food allergy. SPT is readily performed in the clinical setting, and a near infinite number of foods can be evaluated, although extracts are not yet standardized. It is typically the first test used in the evaluation of food allergy. Measurement of sIgE for a wide variety of foods is available in most centers. These tests both evaluate the presence of IgE, which determines sensitization but does not necessarily correlate with clinical reactivity. In an effort to improve diagnostic accuracy, component testing allows the allergist to examine IgE levels against a particular protein of the culprit food. Examining sensitization profiles to specific food allergen components aims to distinguish between sensitized and truly reactive patients.Citation5 Some proposed novel diagnostic tests are in development, but are not yet ready for clinical application.

Management of food allergy relies primarily on allergen avoidance, with prompt emergency care for accidental exposure. Food allergen avoidance is not always effective, as allergens such as milk and egg may be hidden in foods. An estimated 10%–20% of individuals with a diagnosis of anaphylaxis experience recurrent reactions.Citation3,Citation6,Citation7 Despite clear guidelines advising prompt use of an epinephrine autoinjector (EAI) in anaphylaxis, many patients and families do not use an EAI, possibly due to inadequate knowledge and anxiety.Citation8,Citation9 Moreover, the diagnosis of food allergy and the need to carry an EAI are associated with negative effects on quality of life for patients and families alike.Citation10 A recent review found that there were no robust studies examining the effectiveness of injectable epinephrine, antihistamines, systemic glucocorticosteroids, or methylxanthines in the management of anaphylaxis.Citation11 As prompt use of an EAI is the most important step in the acute management of anaphylaxis, we have focused on this treatment modality. Depending on the allergen, many individuals will have lifelong food allergies. Hence, it would be advantageous to have a treatment strategy that allows for food reintroduction and obviates the need to carry an EAI. As such, recent developments in immunotherapy for foods are a very exciting prospect. Incorporating baked milk and egg in the diet may be viewed as a form of immunotherapy for these allergens, while there are other protocols under investigation to desensitize and potentially induce tolerance through gradual introduction of the raw allergen. Other allergens under investigation as candidates for immunotherapy include peanut and peach. In this systematic review, we aim to assess existing and new diagnostic modalities and management options for food allergy. In particular, we will focus on literature published in the last 5 years.

Methods

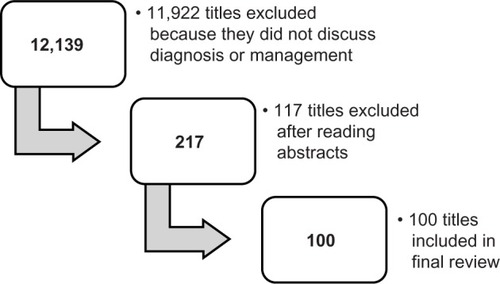

We searched the PubMed database for scientific literature published between January 13, 2009 and January 13, 2014 using the following search criteria: “food allergy” AND “management” OR “diagnosis”. We used the following filters in our search: clinical trial, abstract available, and studies done on humans in any language. Of the available articles, we selected those that were relevant to this review based on the abstract. A team of six readers then further reviewed these articles. The articles have been summarized in regard to food allergy diagnosis and management in and , respectively. Upon initial search of PubMed using the above terms, 12,139 titles appeared. After applying the filters as described, 217 titles remained. Once abstracts had been reviewed, 100 articles were warranted for inclusion in the study ().

Table 1 Diagnosis of food allergy

Table 2 Management of food allergy

Diagnosis

SPT

SPT is the primary diagnostic modality employed by most allergists. It is relatively inexpensive, can be done in the office, results are available immediately, and almost any food can be tested in this manner. Typically, an extract or fresh food is placed on the volar aspect of the forearm and the skin is pricked with an instrument. Fresh food testing can also be accomplished using the “prick-to-prick” method, where the testing device first pricks the food to be tested and is then used to prick the patient. A positive test will result in wheal formation and erythema, indicating sensitization to the allergen tested. Two studies have examined the use of end-point prick testing, or using dilutions of extract or fresh food in SPT, in predicting the outcome of the OFC. In a cohort of patients known to be milk allergic, Bellini et alCitation12 reported that SPT with a wheal diameter greater than 4.5 mm with a 1/10,000 dilution of fresh milk was the best test for discriminating between milk-tolerant and milk-reactive subjects. They proposed using diluted milk after SPT with milk extract to help decide who should proceed to the OFC, noting that those with a positive SPT to the 1/10,000 dilution should avoid the challenge. However, their results reveal that 50% of children with a negative SPT response to diluted milk will have a positive challenge. Tripodi et alCitation13 conducted a similar study using egg extract; however, their results may not be reproducible as extracts were not standardized and may have contained different levels of allergen. Johannsen et alCitation14 evaluated SPT and sIgE to peanut as predictors of OFC outcomes in sensitized preschoolers, demonstrating that 50% of sensitized children could safely ingest peanut. Further, with a combined SPT wheal diameter of <7 mm and sIgE <2 kUA/L for peanut, there is a 5% chance they will react to an OFC. It is reported that a SPT wheal diameter of 8 mm as the threshold for sesame.Citation15 Other researchers suggest a SPT wheal diameters of 8 mm and 7 mm for milk and egg thresholds, respectively.Citation16

sIgE and component testing

Measurement of IgE levels to a specific antigen is another commonly employed method in the diagnosis of food allergies. Like SPT, it assesses sensitization rather than clinical food allergy.Citation17 Component testing strives to delineate sensitized patients from those who will react to a given food. Peanut is one of the more extensively investigated foods in this regard. In evaluating peanut-sIgE, van Nieuwaal et alCitation18 found higher cutoffs for predicting OFC failure compared to previous studies. Ninety percent of participants failed the peanut challenge at an sIgE of 24.8 kUA/L, and 95% at 43.8 kUA/L. The authors attributed these findings to their study population, many of whom were diagnosed with peanut allergy without undergoing DBPCFC. In distinguishing peanut sensitization from reactivity, elevated levels of Ara h 2 tend to be associated with a reactive phenotype,Citation19,Citation20 whereas 89.5% of children with elevated Ara h 8 can safely ingest peanut.Citation21 In comparing peanut-sIgE, Ara h 2, and OFC results, sIgE was the most sensitive test 0.93 (93%), while Ara h 2 was the most specific and had the best positive predictive value.Citation19 Researchers have shown similar results in peanut-allergic Asian children.Citation22 In an effort to develop a more accurate test, Lin et al examined specific sequences of the peanut components and found that using a combination of four peptides Ara h 1, 2, and 3 had 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity.Citation23 The biomarkers generally used to monitor the effect of immunotherapy are sIgE and SPT wheal size. Kulis et alCitation24 examined the effect of peanut sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) on salivary immunoglobulin A levels and found a transient elevation in the treatment group, but, by 1 year, there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Most children with egg allergy will outgrow it. Montesinos et al examined the relationships between sIgE directed towards egg white, ovalbumin, and ovomucoid, and demonstrated that these biomarkers were lower in subjects who outgrew their egg allergy.Citation25 Another recent finding in egg allergy is that many egg-allergic children are able to tolerate baked egg. sIgE to egg white, ovalbumin, and ovomucoid tends to be lower in children who are tolerant to baked egg.Citation26,Citation27

Further studies have examined the role of diagnostic testing in sesame, wheat, and soy allergy. For sesame, sIgE >7 kUA/L or an SPT wheal size >6 mm were both >90% specific in predicting the results of an OFC.Citation28 In a Japanese cohort, the median sIgE level in allergic children was 4.31 kUA/L for wheat and 3.89 kUA/L for soybean.Citation29

It has been previously hypothesized that immunoglobulin G (IgG)-mediated reactions may be involved with food hypersensitivity, and, as such, some health care practitioners measure food-specific IgG levels. However, in a cohort of 5,394 Chinese adults, there was no relationship between food-specific IgG levels and allergic symptoms.Citation30 Given that increased IgG levels to food allergens may indicate tolerance rather than allergy, this test is not used by allergists in their evaluation.Citation31

Food challenges

Food challenges involve feeding the patient incremental doses of a suspected food and observing them for clinical reaction. Ideally, this is done in a double-blind, placebo-controlled manner. However, it is more practical to administer an OFC that is neither blinded nor placebo controlled. Food challenges may be performed to confirm the diagnosis of allergy or to monitor for resolution, and are often necessary due to the poor sensitivity and specificity of SPT and sIgE testing. Fleischer et al found that most children diagnosed with food allergy on the basis of immunoassays were able to reintroduce the suspected food into their diet following challenge.Citation32 Food challenges are also useful in establishing the diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated processes that cannot be detected by SPT or sIgE testing.Citation33 When performed in an appropriate setting, OFCs are an extremely safe procedure. In an evaluation of 701 OFCs performed in 521 patients, 18.8% elicited a reaction. Only 1.7% of those who reacted required treatment with epinephrine.Citation34 Calvani et al reported similar results: among 544 OFCs, 48.3% of patients reacted, although 65.7% had mild reactions; only 2.7% required treatment with epinephrine.Citation35 OFCs have been demonstrated to be a highly reproducible and valid strategy for establishing the diagnosis of food allergy. A recent study exemplified this, with 100% correlation between a positive DBPCFC and a positive single-blind OFC among patients with peanut allergy.Citation36

OFCs have been established as a safe and effective way to diagnose milk allergy.Citation37 An OFC for milk is important for several reasons. Many children will become milk tolerant with time. In fact, between 58.7% and 66% of children with suspected milk allergy will be tolerant to an OFC.Citation37,Citation38 Similar to those with an egg allergy, most milk-allergic children can tolerate baked milk. Bartnikas et al reported that 83% of the milk-allergic children they challenged were able to tolerate baked milk in their diet. In particular, they found that no child with an SPT wheal diameter <7 mm failed the baked milk challenge, and that 90% of those with a wheal diameter under 12 mm passed the baked milk challenge.Citation39 Elimination diets are detrimental to health as they can be associated with nutritional deficiencies and increased anxiety among patients and families. Liberalizing the diet to include safe foods that are tolerated by the patient is essential in improving quality of life.Citation40 OFCs are associated with a transient increase in parental anxiety, but, in the long-term, parents and patients report improved quality of life.Citation41,Citation42

There are several methods by which OFC may be conducted, with many clinicians using individualized protocols. These protocols can vary in terms of timing, dosing, the agent used, and the definition of a positive or negative challenge. In an egg OFC, Escudero et al challenged patients to both dried egg white and raw egg white. They found that 25% of the patients reacted to both, and 75% of the patients reacted to neither, indicating that dried egg white can be used to evaluate raw egg.Citation43 Dried egg white offers several advantages over raw egg white, including storage capacity and palatability. Similarly, Winberg et al sought to validate recipes for use in DBPCFCs to egg, milk, cod, soy, and wheat. Using the same liquid test vehicle for each allergen, they found that children were unable to differentiate test from control doses.Citation44 This provides clinicians with validated recipes that are easy to prepare and effective in concealing antigen.

OFCs and blind food challenges to evaluate immediate IgE-mediated food allergy are typically started with 0.1% to 1% of the total challenge food. If known, the initial OFC dose should be lower than the expected threshold dose. According to one approach, the total amount that should be administered during a gradually escalating OFC equals 8–10 g of a dry food, 16–20 g of meat or fish, and 100 mL of wet food (eg, apple sauce). The recommended dosing interval is 15 minutes.Citation45

Management

Primary prevention

There are many theories regarding the origins of allergy. While we do not fully understand the etiology of allergic disease, much research has focused on how it may be prevented. In a cohort of infants with likely milk or egg allergy, Sicherer et al found that maternal peanut consumption during pregnancy, as well as sIgE to milk and peanut, were linked to an increased risk of having peanut-sIgE >5 kUA/L.Citation46 Similar findings have been reported for tree nut and sesame seeds.Citation47 It is important to note that these studies evaluated sensitization rather than reactivity. Mothers of peanut-allergic children reported higher consumption of peanuts during pregnancy and breastfeeding compared to mothers of non-allergic subjects.Citation48 However, the retrospective design of the study makes recall bias a likely explanation for this finding. In two recent cohort studies assessing clinical peanut allergy, it was reported that higher maternal peanut intake during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of peanut-allergic reaction in offspring.Citation49,Citation50

Other studies have assessed the influence of maternal antioxidants consumption and polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy on allergic disease in children. West et al reported that increased dietary levels of copper during pregnancy were associated with lower rates of wheeze and eczema, but had no effect on food allergy in offspring.Citation51 There was no association between polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy and prevention of allergic disease in offspring.Citation52

Beyond pregnancy, several studies have assessed interventions in infancy that may prevent the development of food allergy. Three studies have assessed the role of probiotic supplementation during infancy on allergic disease in childhood but failed to establish an association.Citation53–Citation55 Similarly, no association was found between fish oil supplementation in infancy and allergic disease.Citation56 Other studies have examined how the timing of food introduction influences acquisition of tolerance. In a case-control study, Grimshaw et al reported that infants with food allergy at 2 years of age tended to have been introduced to solids at less than 16 weeks and were less likely to have received breast milk when cow’s milk was introduced.Citation57 Other studies have examined the timing of introduction of specific foods, namely milk and egg. In a prospective cohort, Katz et al found an overall incidence of IgE-mediated milk allergy of 0.5%. The median age of introduction among milk-tolerant infants was 61.6 days, compared to 116.1 days for milk-allergic infants.Citation58 Koplin et al reported that, compared to introduction of egg between 4 and 6 months of age, delayed introduction was associated with a higher risk of egg allergy, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.6 for those introduced to egg at 10–12 months and 3.4 for those introduced when older than 12 months.Citation59 While the optimal timing for the introduction of foods to induce tolerance remains under investigation, the above studies suggest that delaying food introduction beyond 4–6 months of age may increase the risk for food allergy rather than prevent its development.

Fewer studies have examined factors in childhood that are associated with the development of allergic disease. In a cross-sectional study examining children in an allergy clinic, DeMuth et al found that history of taking antacid medication in children according to parental report was associated with an increased prevalence of food allergy.Citation60 This may be explained by the effects of antacids on gastric pH and subsequent influence on the digestion of proteins.

Complementary and alternative medicines

An estimated 8.4% of Japanese children use complementary and alternative medicines in the management of their food allergies. Among these, herbal teas are the most common (22%), followed by Chinese herbal medicine (18.5%) and lactic acid bacteria (16%).Citation61 Of these therapies, most research has focused on a type of Chinese herbal medicine, food allergy herbal formula 2 (FAHF-2). FAHF-2 is a nine-herb formula manufactured in China using a standardized process and monitored for contaminants using high-performance liquid chromatography.Citation62 Two studies have demonstrated the safety and tolerability of FAHF-2 and offered some evidence of an immunologic modulatory effect. Neither of these studies examined the clinical effect of this formulation.Citation63,Citation64

Allergen avoidance

Several steps are required for the allergic patient to successfully avoid a particular allergen. They must be appropriately diagnosed, clearly understand what foods to avoid, and be able to identify the allergen on a label. For children, there is an added layer of complexity as their caregivers must be proficient in these skills as well.

There is anxiety associated with the diagnosis of food allergy. A study of seafood-allergic children found that 25% of their parents could not recall dietary advice provided by a physician. Nonetheless, 89% of them implemented a safe diet, although it was often more restrictive than needed. Approximately one in five patients had recurrent reactions following diagnosis. Prescription of an EAI was associated with improved adherence to the diet.Citation65 In studies of milk-allergic children, 85% adhered to a milk-free diet, although this cohort received special infant formula reimbursement, which may bias the sample. Moreover, it is unclear whether these children were avoiding milk because of IgE-mediated reactions.Citation66 Milk is prevalent in many foods and may be a “hidden” allergen. Accordingly, accidental exposures to milk are common and observed in up to 40% of children with milk allergy, although these reactions are usually mild (53%).Citation67 There are several options available for milk-allergic patients. One study examined camel milk as an alternative and found it was well tolerated.Citation68 Berni Canani et al examined a new amino acid formula and found that this was a safe alternative for children with milk allergy.Citation69

Labeling practices to alert consumers to food allergens are varied among manufacturers, with many products bearing a “may contain” precautionary label. In an Australian study, 65% of products had precautionary labels for an allergen that was not listed in the ingredients.Citation70 There is a high degree of consumer confusion when it comes to food labeling, with less than 5% of the general population able to correctly identify more than 50% of the terms associated with a given allergen.Citation71 Among food labels, “not suitable” was found to be the most effective in deterring purchase of a product among food-allergic individuals and members of their households.Citation72 Current food-labeling practices benefit neither the consumer nor the manufacturer. The use of a standardized process would be beneficial to both these groups.Citation73

Young children with food allergies require assistance from adults to efficiently avoid allergens. Food is consumed at school, and the teacher plays an important role in the safety of food-allergic children. A survey of Mississippi, USA schools found that 97% had at least one food-allergic child, but only 30% had action plans for these students. Schools were more likely to have action plans when the school nurse had received appropriate information from a physician.Citation74 Similar findings were reported in a Korean study, where 71% of schools relied on parental report of food allergy and 47% had experienced student visits to a school health room due to food allergy. More than 80% relied on self-care without school-wide measures for food allergies.Citation75 Further, there are many misconceptions among teachers regarding food allergy and anaphylaxis. In a survey of primary school teachers, pollen was thought to be the most common agent to cause anaphylaxis. Among foods, egg and strawberry were the leading suspects. Only 10% of teachers surveyed were aware of EAI and only 4% knew how to administer it.Citation76 Training programs on the recognition and management of anaphylaxis should be implemented for teachers and other caregivers. Anaphylaxis action plans can be written by physicians and provided for distribution in daycares and schools.

EAIs

Most individuals with IgE-mediated food allergy are advised to carry an EAI in case of accidental exposure. There are many barriers to the successful use of an EAI, including the ability to recognize the symptoms of anaphylaxis, the availability of an EAI, and understanding of how to use the EAI. There are additional psychological factors at play, as many patients and parents with an EAI do not use it during anaphylaxis, mostly for reasons relating to fear.Citation8 In almost 50% of cases, an EAI is not carried by individuals with food allergy.Citation77–Citation79 Barriers to EAI availability include having the device on one’s person and having a device that has not expired. Similarly, many patients are not skilled in the use of their EAIs, with 62%–87% demonstrating errors in use. Repeated instruction can improve both self-carry practices and the individual’s ability to use an EAI.Citation77,Citation79 While prescription of an EAI is often necessary, it does impact quality of life. Pinczower et al found that prescription of an EAI negatively impacted health-related quality of life, along with being allergic to multiple foods, a history of severe reaction, and patient age 7–12 years.Citation80

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is an attractive option for the treatment of food allergies, as its goal is to induce tolerance in the subject. Patients are considered to be tolerant when they can safely consume the food without following a daily oral food regimen to maintain clinical non-reactivity. In most oral immunotherapy (OIT) protocols, small amounts of allergen are administered orally to patients in gradually increasing amounts, with the immediate goal to induce desensitization. With desensitization, the treated patient manifests a decreased response to the ingested food allergens but must continue to take daily food doses.

Peanut is one of the most common food allergens, and is of great concern given that accidental ingestion of even a very small amount can cause life-threatening reactions and that peanut allergy is typically life-long.

Allergen-specific OIT for peanut allergy aims to induce desensitization and, potentially, tolerance to peanut. However, at present, there is still considerable uncertainty about the effectiveness and safety of this approach.

Three randomized controlled studies have been published on this subject. Anagnostou et al conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of peanut OIT using peanut flour in two phases. In the first phase, 62% of 39 participants achieved desensitization after 6 months of OIT, defined as a negative peanut challenge to 1,400 mg of peanut protein. In the control group, who avoided peanuts, there were no participants who achieved desensitization. In the second phase, the control group underwent OIT, with 54% achieving desensitization. Side effects were generally mild, with gastrointestinal complaints being the most common.Citation81 Varshney et al randomized 28 subjects to receive either OIT with peanut flour or placebo. Initial escalation, build-up, and maintenance phases were followed by an OFC at 1 year with titrated skin prick tests and laboratory studies performed at regular intervals. Three subjects in the treatment group withdrew early because of side effects, but all remaining peanut subjects (n=16) ingested the maximum cumulative dose of 5,000 mg (approximately 20 peanuts) after 1 year versus 280 mg in the placebo group (P<0.001). Several immunological changes accompanied successful completion of the OIT protocol: decreased SPT wheal size and Th2 cytokine production and increased IgG4 and Treg cells. There was no significant change in peanut-sIgE levels. Adverse effects were frequent, but the majority were mild.Citation82

Fleischer et al also published an RCT in 2013 to investigate safety, efficacy, and immunologic effects of peanut SLIT in 40 peanut-allergic children. After 44 weeks of SLIT, 14 of 20 (70%) subjects receiving peanut SLIT were responders, compared with three of 20 (15%) subjects receiving placebo (P<0.001). In peanut SLIT responders, the median successful consumed dose increased from 3.5 to 496 mg. After 68 weeks of SLIT, the median successful consumed dose significantly increased to 996 mg. With regard to side effects, of 10,855 peanut doses administered through to week 44, 63.1% of patients were symptom free; excluding oropharyngeal symptoms, 95.2% were symptom free.Citation83

In 2013, Chin et al published a letter to an editor to retrospectively compare two RCTs of OIT versus SLIT in peanut-allergic children. They found that, after 2 years, OIT was associated with greater immunological changes in sIgE and IgG4 levels basophil activation, and IgE/IgG4 ratio. Clinically, they found that dose thresholds were lower and more variable during DBPCFC at 12 months in SLIT versus OIT.Citation84 Additionally, other small, uncontrolled trials show suggestive evidence that OIT can increase the threshold dose for peanut exposure.Citation85–Citation87

There are few studies published on long-term outcomes of peanut OIT. Vickery et al prospectively followed a group of patients who underwent 5 years of treatment with peanut OIT. They found that 12 of 24 patients (50%) had sustained unresponsiveness to peanut 1 month after discontinuing therapy.Citation88 Adverse effects are common, but OIT appears to be relatively safe if administered in a carefully monitored setting. Nevertheless, there remains concern about safety, with several studies having evaluated this. In a retrospective chart review examining data from five clinics performing peanut OIT, Wasserman et al reported that, among 352 patients receiving 240,351 doses of OIT, there were 95 reactions requiring treatment with epinephrine.Citation89 Two studies have evaluated home dosing, and reported reactions in 2.6%–3.7% of total daily home doses.Citation90,Citation91 In one of these studies, two reactions required epinephrine.Citation91 In the RCT published by Varshney et al,Citation82 47% of the patients had mild-to-moderate side effects requiring antihistamines during the initial rush phase, with two patients requiring epinephrine. During the build-up phase and home doses, none of the peanut OIT patients required epinephrine.

Hofmann et al found that patients were more likely to develop significant allergic symptoms during the initial escalation day than during other phases. Upper respiratory tract (79%) and abdominal (68%) symptoms were the most frequent symptoms at that phase. The risk of having any symptom after the build-up phase was 46% and the risk of reaction with home dosing was 3.5%.Citation91

Yu et al presented data of an ongoing Phase I single-center trial of peanut OIT. Symptoms were mostly mild (84%) and self-resolved or were resolved with antihistamines; 13% were moderate and 3% were severe. Of the severe symptoms, three gastrointestinal reactions required epinephrine. Abdominal pain was the most common reaction, followed by oropharyngeal and lip pruritus. Respiratory symptoms were rare.Citation92

OIT has been explored for other common food allergens including milk and egg. In 2012, Yeung et al published a Cochrane Review on milk OIT (MOIT). At that time, the authors identified five RCTs in order to compare OIT to placebo or avoidance. A total of 196 (106 treatment and 90 control) children were enrolled in these studies. The primary outcome of these studies was successful desensitization, but long-term tolerance was not assessed. According to this Cochrane Review, MOIT was proved to be an effective method of inducing (partially) desensitization. Yeung et al reported that 62% of the children in the MOIT group could tolerate 200 mL of milk versus 8% in the control group. Twenty-five percent of the children tolerated 10–184 mL of milk versus 0% in the control group. In general, the authors described low-quality studies with small numbers and different treatment protocols.Citation93

Since that publication, there has been only one RCT performed, which was by Pajno et al in 2013 and which compared two different maintenance regimens (daily milk versus milk twice a week) over 1 year following successful cow’s milk desensitization. No difference was found in clinical efficacy or adverse effects between the two groups. The levels of sIgG4, sIgE and SPT wheal size were comparable between the intervention and control groups.Citation94

In 2011, Nadeau et al published a pilot study in which they performed rush desensitization to milk using omalizumab. This protocol was successful in 9/10 of the patients. Although all of the patients experienced adverse reactions, most of these were mild and only one case required epinephrine.Citation95

A major pitfall for OIT in general is the frequency of adverse events. Although most are mild and self-limited, there is a risk of severe reactions necessitating treatment with epinephrine. Two studies examined predictors of achieving tolerance and adverse effects. García-Ara et al evaluated the efficacy and safety of an OIT protocol according to the level of sIgE. They found that the lower the sIgE level at baseline, the earlier tolerance was achieved, and that adverse effects were more frequent when sIgE levels were higher.Citation96 Vázquez-Ortiz et al identified three variables associated with reaction persistence throughout the OIT: cow milk-sIgE levels of at least 50 kUA/L, SPT wheal size of ≥9 mm and Sampson severity grades 2, 3 and 4 at baseline food challenge.Citation97

Currently, there is no evidence that MOIT can induce long-term tolerance. In a letter to the editor, Keet et alCitation98 published a follow-up of two studies of MOIT (cow’s milk) after 5 years to evaluate cow’s milk consumption, symptoms, and potential predictors of long-term outcomes. The first study, undertaken by Skripak et al, was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with 20 children.Citation99 The second, performed by Keet et al, was an open-label randomized trial of OIT versus SLIT with 30 children.Citation100 Sixteen subjects were eligible from each study and they were followed up after a median of 4.5 years.

Thirty one percent of patients could tolerate full servings of cow’s milk with minimal or no symptoms. There are several limitations of this report as there was no follow-up serology or SPT, no control group, and no data for quality of life before and after treatment.Citation98

Two studies have evaluated dietary management strategies other than OIT in milk-allergic children. The first study, published in 2010 by Reche et al, compared the clinical tolerance of a hydrolyzed rice protein formula with an extensively hydrolyzed cow’s milk formula (EHCF) in infants with IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. The authors found no significant differences regarding tolerance achievement, adverse reactions, sIgE level, growth, or clinical tolerance.Citation101 In a 2013 trial comparing five feeding regimens in milk-allergic children (EHCF, EHCF + Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, hydrolyzed rice formula, soy formula, and amino acid formula), milk-allergic children who received EHCF alone or in combination with L. rhamnosus GG achieved tolerance at 12 months. Significantly more children achieved tolerance after 12 months than their peers who received hydrolyzed rice formula, soy formula, or amino acid-based formula.Citation69 Both studies were relatively small and larger sample sizes may be needed.

As many egg-allergic patients tolerate baked egg, Leonard et al examined the role of baked egg in acquisition of tolerance. They reported that 89% of egg-allergic patients tolerated baked egg and, over time, 53% became regular egg tolerant, compared to 26% of the control group. Those who tolerated baked egg had lower egg white-sIgE levels. Additionally, inclusion of baked egg in the diet appears to hasten the acquisition of tolerance to regular egg.Citation102

To date, two RCTs of egg OIT have been published. In 2012, Burks et al reported successful desensitization in 55% of their treatment group (n=40) and none of the placebo group (n=15). After 22 months, this increased to 75% of the OIT group. After discontinuation of OIT and avoidance of all egg products for 6–8 weeks, only 28% of the OIT group tolerated egg in an OFC. This study demonstrates successful desensitization, but long-term tolerance was achieved in less than one-third of participants.Citation103 Meglio et al published similar data for a group of ten egg-allergic children, demonstrating that 80% were desensitized over a 6-month period, but they did not examine acquisition of tolerance.Citation104 Tortajada-Girbés et al published a prospective cohort trial of OIT involving 19 egg-allergic children. Most participants (89.5%) reached the target dose of egg and were able to tolerate egg in meals on a weekly basis. There were no severe reactions during this trial, although two participants withdrew as they experienced anaphylaxis with the initial dose of OIT.Citation105 Two small studies have examined a rush protocol for the administration of egg OIT, demonstrating successful desensitization over 5–12 days. Many participants had reactions during OIT, but these were generally mild or moderate in nature.Citation106,Citation107 Ojeda et al examined a home-based egg OIT protocol wherein participants were pretreated with antihistamines. They found that 80.6% of subjects in the intention-to-treat group achieved complete desensitization, tolerating the target dose of one egg, while 3.2% reached incomplete tolerance and 16.2% achieved no tolerance. Children who were tolerant to baked egg at baseline were more likely to achieve tolerance to raw egg throughout the study.Citation108

Two studies have examined SLIT for peach. After 6 months of SLIT with a Pru p 3 extract, the treatment group tolerated higher doses of peach and had a smaller SPT wheal size and increased specific IgG4.Citation109 In a separate study, García et al demonstrated that, among peach-allergic individuals, the most commonly recognized antigen is Pru p 3 (83.3%). sIgE to Pru p 3 rose in both the SLIT treatment group and the control group, but remained elevated only in the treatment group. SPT wheal size decreased in the treatment group.Citation110

Conclusion

While the mainstays of diagnosis and management in food allergy remain relatively unchanged, there are several emerging modalities that offer exciting prospects for the future. Though we rely heavily on SPT, component testing will likely contribute to improved diagnostic accuracy. OFCs are safe when performed appropriately and improve patients’ quality of life. While management strategies are currently limited to allergen avoidance and emergency treatment of accidental exposures, immunotherapy trials offer great promise for developing desensitization. Future studies exploring strategies to induce tolerance are required. Improved diagnostic capabilities and management techniques will revolutionize food allergy diagnosis and management for physicians and patients alike in years to come.

Acknowledgments

Dr Ben-Shoshan is the recipient of the Fonds de recherche du Québec Junior 1 award and the AllerGen NCE emerging clinician scientist award.

Disclosure

Dr Ben-Shoshan is a consultant for Sanofi and Novartis. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NwaruBIHicksteinLPanesarSSRobertsGMuraroASheikhAEAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines GroupPrevalence of common food allergies in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysisAllergy2014698992100724816523

- Ben-ShoshanMTurnbullEClarkeAFood allergy: temporal trends and determinantsCurr Allergy Asthma Rep201212434637222723032

- DeckerWWCampbellRLManivannanVThe etiology and incidence of anaphylaxis in Rochester, Minnesota: a report from the Rochester Epidemiology ProjectJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812261161116518992928

- AseroRFernandez-RivasMKnulstACBruijnzeel-KoomenCADouble-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge in adults in everyday clinical practice: a reappraisal of their limitations and real indicationsCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20099437938519483616

- SanzMLBlázquezABGarciaBEMicroarray of allergenic component-based diagnosis in food allergyCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol201111320420921522063

- González-PérezAAponteZVidaurreCFRodríguezLAAnaphylaxis epidemiology in patients with and patients without asthma: a United Kingdom database reviewJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010125510981104. e120392483

- MullinsRJAnaphylaxis: risk factors for recurrenceClin Exp Allergy20033381033104012911775

- ChadLBen-ShoshanMAsaiYA majority of parents of children with peanut allergy fear using the epinephrine auto-injectorAllergy201368121605160924410784

- Ben-ShoshanMLa VieilleSEismanHAnaphylaxis treated in a Canadian pediatric hospital: incidence, clinical characteristics, triggers, and managementJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131323739741. e323900056

- PrimeauMNKaganRJosephLThe psychological burden of peanut allergy as perceived by adults with peanut allergy and the parents of peanut-allergic childrenClin Exp Allergy20003081135114310931121

- DhamiSPanesarSSRobertsGEAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines GroupManagement of anaphylaxis: a systematic reviewAllergy201469216817524251536

- BelliniFRicciGDondiAPiccinnoVAngeliniFPessionAEnd point prick test: could this new test be used to predict the outcome of oral food challenge in children with cow’s milk allergy?Ital J Pediatr2011375222053846

- TripodiSBusincoADAlessandriCPanettaVRestaniPMatricardiPMPredicting the outcome of oral food challenges with hen’s egg through skin test end-point titrationClin Exp Allergy20093981225123319400898

- JohannsenHNolanRPascoeEMSkin prick testing and peanut-specific IgE can predict peanut challenge outcomes in preschoolchildren with peanut sensitizationClin Exp Allergy2011417994100021429048

- PetersRLAllenKJDharmageSCHealthNuts StudySkin prick test responses and allergen-specific IgE levels as predictors of peanut, egg, and sesame allergy in infantsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2013132487488023891354

- HillDJHeineRGHoskingCSThe diagnostic value of skin prick testing in children with food allergyPediatr Allergy Immunol200415543544115482519

- MehlANiggemannBKeilTWahnUBeyerKSkin prick test and specific serum IgE in the diagnostic evaluation of suspected cow’s milk and hen’s egg allergy in children: does one replace the other?Clin Exp Allergy20124281266127222805474

- van NieuwaalNHLasfarWMeijerYUtility of peanut-specific IgE levels in predicting the outcome of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challengesJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012561391139220304474

- LiebermanJAGlaumannSBatelsonSBorresMPSampsonHANilssonCThe utility of peanut components in the diagnosis of IgE-mediated peanut allergy among distinct populationsJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract201311758224229825

- EllerEBindslev-JensenCClinical value of component-resolved diagnostics in peanut-allergic patientsAllergy201368219019423240588

- AsarnojANilssonCLidholmJPeanut component Ara h 8 sensitization and tolerance to peanutJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130246847222738678

- ChiangWCPonsLKidonMILiewWKGohAWesley BurksASerological and clinical characteristics of children with peanut sensitization in an Asian communityPediatr Allergy Immunol2010212 Pt 2e429e43819702675

- LinJBruniFMFuZA bioinformatics approach to identify patients with symptomatic peanut allergy using peptide microarray immunoassayJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012129513211328. e522444503

- KulisMSabaKKimEHIncreased peanut-specific IgA levels in saliva correlate with food challenge outcomes after peanut sublingual immunotherapyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201212941159116222236732

- MontesinosEMartorellAFélixRCerdáJCEgg white specific IgE levels in serum as clinical reactivity predictors in the course of egg allergy follow-upPediatr Allergy Immunol2010214 Pt 163463919943913

- CaubetJCBencharitiwongRMoshierEGodboldJHSampsonHANowak-WęgrzynASignificance of ovomucoid- and ovalbumin-specific IgE/IgG(4) ratios in egg allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012129373974722277199

- AlessandriCZennaroDScalaEOvomucoid (Gal d 1) specific IgE detected by microarray system predict tolerability to boiled hen’s egg and an increased risk to progress to multiple environmental allergen sensitisationClin Exp Allergy201242344145022168465

- PermaulPStutiusLMSheehanWJSesame allergy: role of specific IgE and skin-prick testing in predicting food challenge resultsAllergy Asthma Proc200930664364820031010

- KomataTSöderströmLBorresMPTachimotoHEbisawaMUsefulness of wheat and soybean specific IgE antibody titers for the diagnosis of food allergyAllergol Int200958459960319776678

- ZengQDongSYWuLXVariable food-specific IgG antibody levels in healthy and symptomatic Chinese adultsPLoS One201381e5361223301096

- LavineEBlood testing for sensitivity, allergy or intolerance to foodCMAJ2012184666666822431905

- FleischerDMBockSASpearsGCOral food challenges in children with a diagnosis of food allergyJ Pediatr20111584578583. e121030035

- JärvinenKMSichererSHDiagnostic oral food challenges: procedures and biomarkersJ Immunol Methods20123831–2303822414488

- LiebermanJACoxALVitaleMSampsonHAOutcomes of office-based, open food challenges in the management of food allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201112851120112221835446

- CalvaniMBertiIFiocchiAOral food challenge: safety, adherence to guidelines and predictive value of skin prick testingPediatr Allergy Immunol201223875576123106528

- GlaumannSNoppAJohanssonSGBorresMPNilssonCOral peanut challenge identifies an allergy but the peanut allergen threshold sensitivity is not reproduciblePLoS One201381e5346523326435

- MendonçaRBFrancoJMCoccoRROpen oral food challenge in the confirmation of cow’s milk allergy mediated by immunoglobulin EAllergol Immunopathol (Madr)2012401253021752525

- DambacherWMde KortEHBlomWMHoubenGFde VriesEDouble-blind placebo-controlled food challenges in children with alleged cow’s milk allergy: prevention of unnecessary elimination diets and determination of eliciting dosesNutr J2013122223394146

- BartnikasLMSheehanWJHoffmanEBPredicting food challenge outcomes for baked milk: role of specific IgE and skin prick testingAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20121095309313. e123062384

- IndinnimeoLBaldiniLDe VittoriVDuration of a cow-milk exclusion diet worsens parents’ perception of quality of life in children with food allergiesBMC Pediatr20131320324308381

- van der VeldeJLFlokstra-de BlokBMde GrootHFood allergy-related quality of life after double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges in adults, adolescents, and childrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130511361143. e222835403

- KnibbRCIbrahimNFStiefelGThe psychological impact of diagnostic food challenges to confirm the resolution of peanut or tree nut allergyClin Exp Allergy201242345145922093150

- EscuderoCSánchez-GarcíaSRodríguez del RíoPDehydrated egg white: an allergen source for improving efficacy and safety in the diagnosis and treatment for egg allergyPediatr Allergy Immunol201324326326923551792

- WinbergANordströmLStrinnholmÅNew validated recipes for double-blind placebo-controlled low-dose food challengesPediatr Allergy Immunol201324328228723590418

- Nowak-WegrzynAAssa’adAHBahnaSLBockSASichererSHTeuberSSAdverse Reactions to Food Committee of American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and ImmunologyWork Group report: oral food challenge testingJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009123Suppl 6S365S38319500710

- SichererSHWoodRAStableinDMaternal consumption of peanut during pregnancy is associated with peanut sensitization in atopic infantsJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012661191119721035177

- HsuJTMissmerSAYoungMCPrenatal food allergen exposures and odds of childhood peanut, tree nut, or sesame seed sensitizationAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2013111539139624125147

- DesRochesAInfante-RivardCParadisLParadisJHaddadEPeanut allergy: is maternal transmission of antigens during pregnancy and breastfeeding a risk factor?J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol2010204289294

- BunyavanichSRifas-ShimanSLPlatts-MillsTAPeanut, milk, and wheat intake during pregnancy is associated with reduced allergy and asthma in childrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol201413351373138224522094

- FrazierALCamargoCAJrMalspeisSWillettWCYoungMCProspective study of peripregnancy consumption of peanuts or tree nuts by mothers and the risk of peanut or tree nut allergy in their offspringJAMA Pediatr2014168215616224366539

- WestCEDunstanJMcCarthySAssociations between maternal antioxidant intakes in pregnancy and infant allergic outcomesNutrients20124111747175823201845

- PalmerDJSullivanTGoldMSEffect of n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in pregnancy on infants’ allergies in first year of life: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012344e18422294737

- JensenMPMeldrumSTaylorALDunstanJAPrescottSLEarly probiotic supplementation for allergy prevention: long-term outcomesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130512091211. e522958946

- WestCEHammarströmMLHernellOProbiotics in primary prevention of allergic disease – follow-up at 8–9 years of ageAllergy20136881015102023895631

- LooEXLlanoraGVLuQAwMMLeeBWShekLPSupplementation with probiotics in the first 6 months of life did not protect against eczema and allergy in at-risk Asian infants: a 5-year follow-upInt Arch Allergy Immunol20141631252824247661

- D’VazNMeldrumSJDunstanJAPostnatal fish oil supplementation in high-risk infants to prevent allergy: randomized controlled trialPediatrics2012130467468222945403

- GrimshawKEMaskellJOliverEMIntroduction of complementary foods and the relationship to food allergyPediatrics20131326e1529e153824249826

- KatzYRajuanNGoldbergMREarly exposure to cow’s milk protein is protective against IgE-mediated cow’s milk protein allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012617782. e120541249

- KoplinJJOsborneNJWakeMCan early introduction of egg prevent egg allergy in infants? A population-based studyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010126480781320920771

- DeMuthKStecenkoASullivanKFitzpatrickARelationship between treatment with antacid medication and the prevalence of food allergy in childrenAllergy Asthma Proc201334322723223676571

- NakanoTShimojoNOkamotoYThe use of complementary and alternative medicine by pediatric food-allergic patients in JapanInt Arch Allergy Immunol2012159441041522846790

- WangJLiXMChinese herbal therapy for the treatment of food allergyCurr Allergy Asthma Rep201212433233822581122

- WangJPatilSPYangNSafety, tolerability, and immunologic effects of a food allergy herbal formula in food allergic individuals: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose escalation, phase 1 studyAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20101051758420642207

- PatilSPWangJSongYClinical safety of Food Allergy Herbal Formula-2 (FAHF-2) and inhibitory effect on basophils from patients with food allergy: extended phase I studyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011128612591265. e221794906

- NgIETurnerPJKempASCampbellDEParental perceptions and dietary adherence in children with seafood allergyPediatr Allergy Immunol201122772072821749460

- TuokkolaJKailaMKronberg-KippiläCCow’s milk allergy in children: adherence to a therapeutic elimination diet and reintroduction of milk into the dietEur J Clin Nutr201064101080108520683464

- Boyano-MartínezTGarcía-AraCPedrosaMDíaz-PenaJMQuirceSAccidental allergic reactions in children allergic to cow’s milk proteinsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009123488388819232704

- EhlayelMSHazeimaKAAl-MesaifriFBenerACamel milk: an alternative for cow’s milk allergy in childrenAllergy Asthma Proc201132325525821703103

- Berni CananiRNocerinoRTerrinGFormula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: a prospective multicenter studyJ Pediatr20131633771777. e123582142

- ZurzoloGAMathaiMLKoplinJJAllenKJPrecautionary allergen labelling following new labelling practice in AustraliaJ Paediatr Child Health2013494E306E31023489385

- SakellariouASinaniotisADamianidouLPapadopoulosNGVassilopoulouEFood allergen labelling and consumer confusionAllergy201065453453519860786

- Ben-ShoshanMShethSHarringtonDEffect of precautionary statements on the purchasing practices of Canadians directly and indirectly affected by food allergiesJ Allergy Clin Immunol201212951401140422421266

- TurnerPJKempASCampbellDEAdvisory food labels: consumers with allergies need more than “traces” of informationBMJ2011343d618021998345

- PulciniJMMarshallGDJrNaveedAPresence of food allergy emergency action plans in MississippiAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2011107212713221802020

- KimSYoonJKwonSKimJHanYCurrent status of managing food allergies in schools in Seoul, KoreaJ Child Health Care201216440641623059601

- ErcanHOzenAKaratepeHBerberMCengizlierRPrimary school teachers’ knowledge about and attitudes toward anaphylaxisPediatr Allergy Immunol201223542843222554351

- DeMuthKAFitzpatrickAMEpinephrine autoinjector availability among children with food allergyAllergy Asthma Proc201132429530021781405

- SpinaJLMcIntyreCLPulciniJAAn intervention to increase high school students’ compliance with carrying auto-injectable epinephrine: a MASNRN studyJ Sch Nurs201228323023722217467

- SegalNGartyBZHofferVLevyYEffect of instruction on the ability to use a self-administered epinephrine injectorIsr Med Assoc J2012141141722624436

- PinczowerGDBertalliNABussmannNThe effect of provision of an adrenaline autoinjector on quality of life in children with food allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131311238240. e123199601

- AnagnostouKIslamSKingYAssessing the efficacy of oral immunotherapy for the desensitisation of peanut allergy in children (STOP II): a phase 2 randomised controlled trialLancet201438399251297130424485709

- VarshneyPJonesSMScurlockAMA randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic responseJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011127365466021377034

- FleischerDMBurksAWVickeryBPConsortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR)Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131311119.e1127.e723265698

- ChinSJVickeryBPKulisMDSublingual versus oral immunotherapy for peanut-allergic children: a retrospective comparisonJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131322476478. e223534975

- ClarkATIslamSKingYDeightonJAnagnostouKEwanPWSuccessful oral tolerance induction in severe peanut allergyAllergy20096481218122019226304

- JonesSMPonsLRobertsJLClinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapyJ Allergy Clin Immunol20091242292300300. e1e9719577283

- MansfieldLEOral immunotherapy for peanut allergy in clinical practice is readyAllergy Asthma Proc201334320520923676569

- VickeryBPScurlockAMKulisMSustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2014133246847524361082

- WassermanRLFactorJMBakerJWOral immunotherapy for peanut allergy: multipractice experience with epinephrine-treated reactionsJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract201421919624565775

- BlumchenKUlbrichtHStadenUOral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxisJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012618391. e120542324

- HofmannAMScurlockAMJonesSMSafety of a peanut oral immunotherapy protocol in children with peanut allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol20091242286291291. e1e619477496

- YuGPWeldonBNeale-MaySNadeauKCThe safety of peanut oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic subjects in a single-center trialInt Arch Allergy Immunol2012159217918222678151

- YeungJPKlodaLAMcDevittJBen-ShoshanMAlizadehfarROral immunotherapy for milk allergyCochrane Database Syst Rev201211CD00954223152278

- PajnoGBCaminitiLSalzanoGComparison between two maintenance feeding regimens after successful cow’s milk oral desensitizationPediatr Allergy Immunol201324437638123692328

- NadeauKCSchneiderLCHoyteLBorrasIUmetsuDTRapid oral desensitization in combination with omalizumab therapy in patients with cow’s milk allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201112761622162421546071

- García-AraCPedrosaMBelverMTMartín-MuñozMFQuirceSBoyano-MartínezTEfficacy and safety of oral desensitization in children with cow’s milk allergy according to their serum specific IgE levelAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2013110429029423535095

- Vázquez-OrtizMAlvaro-LozanoMAlsinaLSafety and predictors of adverse events during oral immunotherapy for milk allergy: severity of reaction at oral challenge, specific IgE and prick testClin Exp Allergy20134319210223278884

- KeetCASeopaulSKnorrSNarisetySSkripakJWoodRALong-term follow-up of oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131323737739. e623806635

- SkripakJMNashSDRowleyHA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812261154116018951617

- KeetCAFrischmeyer-GuerrerioPAThyagarajanAThe safety and efficacy of sublingual and oral immunotherapy for milk allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012129244845522130425

- RecheMPascualCFiandorAThe effect of a partially hydrolysed formula based on rice protein in the treatment of infants with cow’s milk protein allergyPediatr Allergy Immunol2010214 Pt 157758520337976

- LeonardSASampsonHASichererSHDietary baked egg accelerates resolution of egg allergy in childrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol20121302473480. e122846751

- BurksAWJonesSMWoodRAConsortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR)Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in childrenN Engl J Med2012367323324322808958

- MeglioPGiampietroPGCarelloRGabrieleIAvitabileSGalliEOral food desensitization in children with IgE-mediated hen’s egg allergy: a new protocol with raw hen’s eggPediatr Allergy Immunol2013241758322882430

- Tortajada-GirbésMPorcar-AlmelaMMartorell-GiménezLTallón-GuerolaMGracia-AntequeraMCodoñer-FranchPSpecific oral tolerance induction (SOTI) to egg: our experience with 19 childrenJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol20122217577

- ItohNItagakiYKuriharaKRush specific oral tolerance induction in school-age children with severe egg allergy: one year follow upAllergol Int2010591435119946197

- García RodríguezRUrraJMFeo-BritoFOral rush desensitization to egg: efficacy and safetyClin Exp Allergy20114191289129621457166

- OjedaPOjedaIRubioGPinedaFHome-based oral immunotherapy protocol with pasteurized egg for children allergic to hen’s eggIsr Med Assoc J2012141343922624440

- Fernández-RivasMGarrido FernándezSNadalJARandomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual immunotherapy with a Pru p 3 quantified peach extractAllergy200964687688319183164

- GarcíaBEGonzález-ManceboEBarberDSublingual immunotherapy in peach allergy: monitoring molecular sensitizations and reactivity to apple fruit and Platanus pollenJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol2010206514520

- CorreaFFVieiraMCYamamotoDRSperidião PdaGde MoraisMBOpen challenge for the diagnosis of cow’s milk protein allergyJ Pediatr (Rio J)201086216316620361120

- MuddKPaterakisMCurtin-BrosnanJMatsuiEWoodRPredicting outcome of repeat milk, egg, or peanut oral food challengesJ Allergy Clin Immunol200912451115111619895997

- HagelAFdeRossiTZopfYMast cell tryptase levels in gut mucosa in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms caused by food allergyInt Arch Allergy Immunol2013160435035523183101

- Berni CananiRNocerinoRLeoneLTolerance to a new free amino acid-based formula in children with IgE or non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy: a randomized controlled clinical trialBMC Pediatr2013132423418822

- SollerLFragapaneJBen-ShoshanMPossession of epinephrine auto-injectors by Canadians with food allergiesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011128242642821684589

- SimonsESichererSHSimonsFETiming the transfer of responsibilities for anaphylaxis recognition and use of an epinephrine auto-injector from adults to children and teenagers: pediatric allergists’ perspectiveAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2012108532132522541402

- SampsonHALeungDYBurksAWA phase II, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled oral food challenge trial of Xolair (omalizumab) in peanut allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011127513091310. e121397314

- SheikhANurmatovUVenderboschIBischoffEOral immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy: systematic review of six case series studiesPrim Care Respir J2012211414921938350

- PascalMKonstantinouGNMasilamaniMLiebermanJSampsonHAIn silico prediction of Ara h 2 T cell epitopes in peanut-allergic childrenClin Exp Allergy201343111612723278886

- KimJLeeJYHanYAhnKSignificance of Ara h 2 in clinical reactivity and effect of cooking methods on allergenicityAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20131101343823244656

- RestaniPBallabioCDi LorenzoCTripodiSFiocchiAMolecular aspects of milk allergens and their role in clinical eventsAnal Bioanal Chem20093951475619578836