Abstract

Triticum aestivum (bread wheat) is the most widely grown crop worldwide. In genetically predisposed individuals, wheat can cause specific immune responses. A food allergy to wheat is characterized by T helper type 2 activation which can result in immunoglobulin E (IgE) and non-IgE mediated reactions. IgE mediated reactions are immediate, are characterized by the presence of wheat-specific IgE antibodies, and can be life-threatening. Non-IgE mediated reactions are characterized by chronic eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract. IgE mediated responses to wheat can be related to wheat ingestion (food allergy) or wheat inhalation (respiratory allergy). A food allergy to wheat is more common in children and can be associated with a severe reaction such as anaphylaxis and wheat-dependent, exercise-induced anaphylaxis. An inhalation induced IgE mediated wheat allergy can cause baker’s asthma or rhinitis, which are common occupational diseases in workers who have significant repetitive exposure to wheat flour, such as bakers. Non-IgE mediated food allergy reactions to wheat are mainly eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) or eosinophilic gastritis (EG), which are both characterized by chronic eosinophilic inflammation. EG is a systemic disease, and is associated with severe inflammation that requires oral steroids to resolve. EoE is a less severe disease, which can lead to complications in feeding intolerance and fibrosis. In both EoE and EG, wheat allergy diagnosis is based on both an elimination diet preceded by a tissue biopsy obtained by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in order to show the effectiveness of the diet. Diagnosis of IgE mediated wheat allergy is based on the medical history, the detection of specific IgE to wheat, and oral food challenges. Currently, the main treatment of a wheat allergy is based on avoidance of wheat altogether. However, in the near future immunotherapy may represent a valid way to treat IgE mediated reactions to wheat.

Introduction

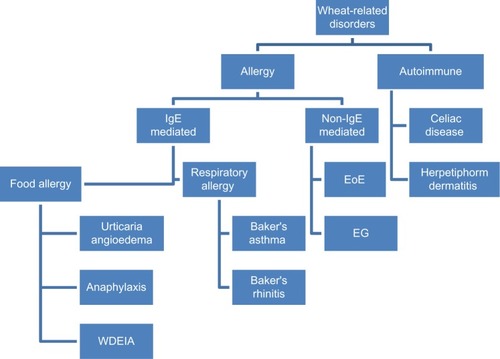

Triticum aestivum (bread wheat) is the most widely grown crop worldwide due being easy to grow in different climates and delivering high yields.Citation1 Moreover, wheat has a high nutritional value, high palatability, and can be processed into many foods, such as breads, pasta, pizza, bulgur, couscous, and in drinks such as beer.Citation1 However, wheat is an increasingly recognized trigger for immune mediated food allergies, both immunoglobulin E (IgE) and non-IgE mediated ().Citation1

Figure 1 Diagram of immune reaction to wheat.

These reactions are typically characterized by a T helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytic inflammation with predominant Th2 cytokines expression (ie, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-5). Th2 inflammation can lead B cells to produce IgE antibodies specific to certain foods (in IgE mediated food allergy), or can lead to a chronic cellular inflammation often characterized by the presence of T cell and eosinophils, which is a much less understood pathogenetic mechanism (non-IgE mediated food allergy).Citation2 This paper will review the literature on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management on the most common IgE mediated and non-IgE mediated food allergies triggered by wheat.

Ingestion of wheat can cause non-Th2 inflammatory reactions, such as celiac disease in genetically susceptible individuals (ie, carriers of HLA class II DQ2 or DQ8).1 In celiac disease gluten proteins from wheat, rye, and barely elicit a T helper type 1 mediated inflammation, which is similar to the one observed in autoimmune diseases.Citation1 Current reviews focus only on food allergy reactions to wheat ().

IgE-mediated reactions to wheat

Epidemiology

IgE mediated reactions to wheat are well-known and can be due to either ingestion (food allergy) or inhalation (respiratory allergy) ().

A food allergy to wheat manifests with a variety of symptoms that include urticaria/angioedema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, abdominal pain, vomiting, acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis, and exercise-induced anaphylaxis (EIA).Citation3–Citation5 The prevalence of IgE mediated food allergy to wheat confirmed by the food challenge is unknown. Data from positive skin prick tests (SPTs) indicates that up to 3% of the general American pediatric population have a food allergy to wheat, however, it is more likely estimated to be 0.2% to 1%.Citation6–Citation11 Children have a higher prevalence of food allergy to wheat compared to adults, especially if wheat was introduced after 6 months of age.Citation7 The increased prevalence in children compared to adults can be explained by the fact that most patients outgrow their allergy by the age of 16 years.Citation12 Keet et al reported that children tend to outgrow wheat allergies with a resolution rate of 65% by the age of 12 years.Citation12 Although it was reported that higher wheat IgE levels were associated with poorer outcomes, children outgrew their wheat allergy with even the highest levels of wheat IgE.Citation12

Wheat has been increasingly reported to be a risk factor for severe anaphylactic as well as for wheat-dependent, exercise-induced anaphylaxis (WDEIA).Citation3,Citation13–Citation15 In a population of children allergic to wheat, more than 50% had experienced anaphylaxis upon wheat ingestion.Citation3 Cianferoni et al also reported that wheat could be involved in food-induced near-fatal or severe anaphylaxis in a study of 1,000 patients with a food allergy.Citation3

EIA is a particular type of anaphylaxis that occurs while performing intense exercise, and may occur independently of food ingestion (EIA) or in close relationship with the timing of food ingestion (food dependent EIA [FDEIA], 30%–50% of EIA).Citation16 FDEIA is diagnosed when anaphylactic episodes occur after the ingestion of a food that is otherwise well tolerated preceding intense exercise (up to 6 hours later, but usually within 1–3 hours).Citation4 Wheat is now recognized as an important and frequent cause of FDEIA, also called WDEIA. WDEIA can manifest at any age, with teens and adults without any prior history of food allergy to be the most affected.Citation16

Respiratory IgE mediated allergies to wheat are represented by baker’s asthma or rhinitis, and are often associated as occupational diseases. The incidence of bakers’ asthma range from 1%–10% of bakers, and the incidence of rhinitis range from 18%–29%.Citation17,Citation18 Respiratory IgE mediated allergies tend to be more frequent in atopic subjects who are exposed to high levels of wheat allergens for several hours per day. The majority of affected individuals did not suffer from asthma before developing the occupational disease.Citation18

Pathogenesis

Classic IgE mediated reactions to a food allergen are immediate, reproducible, and food-specific IgE can be demonstrated. The clinical manifestations are due to the mediator release (ie, histamine, platelets activator factor, and leukotrienes) from mast cells and basophils.Citation19,Citation20 When a specific allergen engages two specific IgE antibodies bound to their high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) it induces the cross link of the FcεRI and causes the activation of mast cell and basophils. IgE production against a certain allergen, including wheat, is believed to be due to a breach in oral tolerance and a consequence of Th2-biased immune dysregulation that induces sensitization and B-cell specific allergen IgE production.Citation21–Citation25 Both individual genetic characteristics and environmental factors play a role in favoring such immune dysregulation.Citation22,Citation26,Citation27 Moreover, the intrinsic properties of food allergens also contribute to whether the allergen favors allergic immune responses. Indeed the “major” food allergens are 10 to 70 kDa water-soluble glycoproteins and are relatively stable to heat, acid, and proteases degradation.Citation28

The protein content in wheat represents 10%–15% of the wheat grain dry weight. Protein can be classified into two fractions based on their solubility in salt: 1) the salt soluble fraction includes albumins and globulin and represents 15%–20% of total proteins; this fraction includes amylase/trypsin inhibitor subunit as well as other proteins such as lipid transfer protiens;Citation29 and 2) the salt insoluble fraction includes gliadin and gluten and represents approximately 80% of wheat protein content, with gluten comprising about half of such fraction.Citation5,Citation30,Citation31

The major allergens of wheat are listed in . α-Amylase/trypsin inhibitor binds to specific IgE and is one of the most common wheat allergens implicated in baker’s asthma,Citation5 anaphylaxis, and in some cases of WDEIA.Citation29 It is present in raw and cooked wheat and appears to be heat resistant and lacks significant cross-reactivity to grass pollen allergens.Citation29 Water insoluble ω-5-gliadin (Tri a 19) has been identified as a major allergen in Finnish subjects with WDEIA.Citation15,Citation30,Citation31

Table 1 Allergens in wheat flour

Tri a 37 is a plant defense protein and is highly expressed in wheat seeds. It is highly stable and resistant to heat and digestion. Therefore, this protein can act as a potent allergen and those who have IgE antibodies against Tri a 37 have a four fold increased risk of severe allergic symptoms upon wheat ingestion.Citation32–Citation34 Nonspecific lipid transfer protein (nsLTP or Tri a 14) has been shown to be an important allergen for IgE mediated food allergies (especially in Italian children), WDEIA and baker’s asthma.Citation29,Citation35,Citation36

Sanchez-Monge et alCitation37 and Yamashita et alCitation38 identified peroxidase, an IgE-binding protein of 36 kDa from wheat flour. Approximately 60% of patients with baker’s asthma displayed specific IgE to peroxidase. Thioredoxins are 12–14 kDa storage proteins present in wheat seeds and have been recognized as a wheat allergen, Tri a 25, able to induce baker’s asthma.Citation39–Citation41 Serine proteinase inhibitor, a 9.9 kDa protein, is mainly expressed in mature seeds and has been found to be an allergen important in 14%–27% of Spanish patients with baker’s asthma.Citation42,Citation43 Thaumatin-like proteins are salt-soluble proteins that are part of pathogenesis-related proteins in the wheat flour and have a molecular weight from 21 to 26 kDa. They are allergenic and have been found to be able to sensitize 30%–45% of Finnish patients with baker’s asthma.Citation44

Several of the major water/salt-insoluble wheat flour proteins (prolamins), including by α-, β-, γ-, and ω-gliadins; and low-molecular-weight (LMW) glutenin subunits appear to be able to bind to IgE and to be implicated in baker’s asthma. For example, the 12% of patients with baker’s asthma had IgE reactive αβ-gliadin (molecular weight of 20 kDa) and 33% showed sensitization to natural total gliadin.Citation45

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of an IgE mediated wheat allergy is based on an accurate history that documents the symptoms specific of IgE mediated food allergy to wheat, WDEIA, or occupational respiratory allergies to wheat flour.Citation12,Citation15,Citation18 When these symptoms occur within 1–3 hours of wheat exposure the allergy to wheat needs to be confirmed by measuring IgE specific to wheat by SPT or in the serum IgE (sIgE). The presence of specific sIgE to wheat without a clear history of symptoms after wheat exposure is not diagnostic as many people can be sensitive to wheat but can tolerate wheat exposure, especially in grass pollen sensitive individuals.Citation46,Citation47 Indeed patients with grass pollen sensitivity carry IgE specific for cereal derived allergens and several studies have reported cross-reactivity between wheat flour and grass pollen due to common IgE epitopes in wheat flour and grass pollen proteins.Citation46,Citation47 Furthermore, a diagnosis based on wheat flour extract does not allow discrimination between patients suffering from a respiratory allergy and those suffering from a food allergy to wheat. Finally, the characteristic extractability properties of wheat grain proteins have significant implication for commercially available diagnostic products. For example, the wheat ImmunoCAP® contains a significantly higher amount of salt-soluble fraction, whereas the salt insoluble fraction is detected by glutenin and/or ω-5 gliadin ImmunoCAP.Citation5

The cutoff levels for specific sIgE for wheat which predict a true allergy to wheat, as well as the confirmatory gold standard challenges, vary depending on which disease needs to be diagnosed: IgE mediated food allergy to wheat, WDEIA, or baker’s asthma.

In the last few years there has been significant advances in the description of many allergens that may cause respiratory and/or IgE mediated food allergies (). However, none have reached a high specificity and sensitivity to become a gold standard for the diagnosis of wheat allergy and therefore, the precise diagnosis still relies on specific clinical standardized challenges done under medical supervision.Citation3,Citation17

A food allergy to wheat manifests with a variety of symptoms that include urticaria/angioedema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, abdominal pain, vomiting, acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis, and EIA, all of which may start within 2 hours after the first exposure to wheat.Citation3–Citation5 Once a food allergy to wheat is suspected, the diagnosis needs to be confirmed by demonstrating specific IgE against wheat. The cutoff levels of IgE that can predict whether the reaction is a true wheat allergy in >90% of patients is not well established, with most studies showing that children even with high levels of IgE (>20 kU/L) can tolerate certain foods when they undergo an oral food challenge (OFC) to wheat ().Citation12,Citation48–Citation50 Similarly, IgE in serum cannot predict whether a child will become tolerant after a period of avoidance or the severity of their reaction.Citation3,Citation51 Therefore, OFCs remain mandatory where there is a no clear history of IgE mediated reaction to wheat, even if IgE specific to wheat can be demonstrated.Citation3,Citation48,Citation49 Most studies have found that wheat OFCs are generally safe, with a rate of failure (30%–50%) and use of epinephrine (10%–20%) similar to other foods (ie, milk, egg, and peanuts), but near fatal reactions can occur and therefore they should be performed by health care providers trained in taking care of patients who have anaphylaxis.Citation3,Citation4 The OFC will therefore be essential to rule out conditions that can mimic an IgE mediated food allergy ().

Table 2 Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs), and negative predictive values (NPVs) of SPT and serum IgE for the diagnosis of food allergy to wheat

Table 3 Differential diagnosis of IgE mediated allergy to wheat

An accurate diagnosis of WDEIA is extremely important to avoid further severe reactions. However, a prolonged time lag (32–62 months) to diagnosis is very frequent due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of recognition from physicians.Citation15 Indeed WDEIA is often mistaken for other more common diseases such as urticaria, EIA, or idiopathic anaphylaxis ().Citation15 Given how the disease is, the diagnosis is extremely dependent on the clinician ability to suspect the disease based on an accurate clinical history.Citation52 Clinical presentations of WDEIA include pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, flushing, shortness of breath, dysphagia, chest tightness, syncope, profuse sweating, headache, nausea, diarrhea, colicky abdominal pain, throat closing, and hoarseness that occurs while performing intense exercise following a meal which included wheat in the 4 hours preceding the onset of WDEIA.Citation16 In patients with suspected WDEIA, SPT, or specific IgE to wheat, gluten and ω-5 gliadin should be performed.Citation15,Citation30,Citation31 In a questionable diagnosis, an OFC followed by a maximal exercise on a treadmill may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.Citation15 These are high risk procedures, however, as the amount of food given and the intensity of exercise required to induce a reaction cannot be well controlled, and severe anaphylactic reactions have been reported.Citation15,Citation54,Citation55 A negative challenge does not rule out WDEIA because several cofactors may be missed in a controlled challenge environment (ie, the intensity of exercise, pollen exposure, concomitant ingestions of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol, and the presence of menses in females).Citation15,Citation54,Citation55 A recent study has indeed shown that alcohol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are a significant risk factor for WDEIA, and can induce WDEIA even in the absence of exercise in a small subgroup of patients.Citation55 Like for any anaphylactic episode, elevated serum tryptase levels have been reported in subjects with WDEIA following an acute episode and can be helpful in determining the diagnosis if measured within 6 hours of an acute reaction.Citation16

As for every type of occupational disease, the diagnosis of baker’s asthma or rhinitis needs to be confirmed by objective methods because the diagnosis has significant social and financial impact.Citation17,Citation18 The diagnosis of baker’s asthma or allergic rhinitis is based on clinical history, the presence of specific IgE to wheat and, in selected individuals, a positive nasal or bronchial response to provocation.Citation17,Citation18 Any new onset of asthma or allergic rhinitis in a worker exposed to significant wheat allergen should raise suspicion of a respiratory allergy to wheat. A good occupational history, including not only the current job but also past jobs and exposure, is very important.Citation18 The sensitivity of SPTs and allergen-specific sIgE can be 74%–100% for higher levels of specific wheat IgE.Citation56 In one study with over a 100 patients with baker’s asthma,Citation56 the minimum cutoff values with positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% were 2.32 kU/L for specific wheat IgE and 5.0 mm for wheat on SPT with wheat flour extracts. If a patient has no or low levels of specific IgE against wheat, challenges with flour may be important in patients with typical symptoms of baker’s asthma or allergic rhinitis.Citation56 Indeed, this disorder has been classically considered a form of allergic asthma mediated by IgE antibodies specific to cereal flour antigens, mainly wheat,Citation9 but other cereals (ie, rye, barley, and rice), flours from different sources (ie, soybean, buckwheat, and lupine), additives and contaminants present in flours (ie, enzymes, egg proteins, storage mites, molds, and insects) are also capable of causing IgE-mediated occupational asthma. Exposure to endotoxins have been reported among agricultural and grain elevator workers and mimic IgE mediated occupational asthma.Citation18 Finally, several other conditions such as non-wheat induced allergic asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic eosinophilic bronchitis, heart insufficiency, non-wheat induced allergic rhinitis, and rhinitis medicamentosa may mimic the wheat induced respiratory occupational diseases.Citation18 To confirm wheat is the trigger of occupational asthma, it is important to demonstrate the presence of wheat allergen in the dust to which the worker is exposed to, and to do appropriate standardized clinical challenges under medical supervision when necessary.Citation18

Demonstration of exposure to wheat allergen flour as measured by methods such as inhibition enzyme immunoassay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay inhibition, or an anti-wheat IgG4 serum, is important because epidemiological studies have shown that work-related sensitization risk is negligible when exposure to 0.2 mg/m3 of wheat allergen or 0.5 mg/m3 of inhalable dust during a work shift, and it increases proportionally to the levels of the allergen and the length of exposure to it.Citation57–Citation59

The gold standard to confirm the diagnosis of a wheat induced occupational therapy remains the bronchial challenge test. This test is typically performed by nebulization of commercial aqueous flour solutions in increasing concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 mg/mL by tidal volume breathing for 10 minutes) or by inhaling wheat flour dust (commercially available or obtained from the workplace) filled in capsules via spinhaler (King Pharmaceutical, Tennessee, TN, USA).Citation56,Citation60 Lung function can be measured by spirometry or by pletismography.Citation56,Citation60 Baker’s asthma is diagnosed if a bronchial provocation test induces at least a 20% decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 second or a threefold increase in nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity accompanied by an increase in sputum eosinophilia.Citation17

Molecular diagnosis of specific wheat IgE will reduce the necessity to do oral and inhaled wheat challenges in the future ().Citation61,Citation62

Management

At the moment, management of IgE mediated wheat allergy is mainly based on avoidance both in food and inhaled wheat allergens.

Patients with a food allergy to wheat must be trained to identify relevant food allergens in the labels, and written instruction should be given to effectively eliminate wheat from their diet. In the USA since 2005, Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 has been enacted to help with reading labels to prevent the accidental exposure to foods for eight of the most common food allergens (milk, egg, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, and wheat). Similar legislation have been introduced in Japan, Europe, and Australia.Citation2

In case of accidental exposure and anaphylactic reaction, epinephrine administration with a self-injector device is the lifesaving treatment. This comes in strengths of either 0.15 or 0.3 mg, and is injected into the vastus lateralis muscle (lateral thigh). Based on the most recent guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, 0.15 mg autoinjector should be used in children weighing less than or equal to 25 kg (55 lbs), including healthy infants weighing less than 10 kg.Citation4 The dose may be repeated at intervals of at least 5 minutes if necessary.Citation4 After self-injection of epinephrine the patient needs to be seen at an emergency room, even if epinephrine has been effective and symptoms are resolved, as the effects of epinephrine are short-lived (approximately 20 minutes) and the reaction may need further treatment.Citation4 All other treatments such as antihistamines, glucocorticoids, and β-agonists, either alone or in combination, are to be considered ancillary in the treatment of anaphylaxis.Citation4

One promising way for treatment of a food allergy is immunotherapy. Currently, there are three techniques being studied: oral immunotherapy (OIT), sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), and epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).Citation64 OIT and SLIT are based on the principle of slowly increasing the amount of food ingested in order to avoid experiencing systemic reactions.Citation64 OIT is the immunotherapeutic treatment with the largest body of evidence, having a decade-long experience in clinical trials. In several clinical trials, OIT for milk, egg, and peanuts is associated with up to 90% of desensitization status in short-term trials and up to 30% in longer-term responses to therapy, when the food is no longer eaten everyday. For example, after an OIT protocol trial for peanuts, 25 out of 25 patients that completed the protocol (89% of the 28 initially enrolled patients) were able to tolerate 5,000 mg of peanuts (equivalent to 20 peanuts), whereas the placebo treated patients could only consume a mean of 280 mg of peanuts (range: 0–1,900 mg).Citation65 Similar results have been reported after milk OIT trials.Citation66 OIT desensitization rates for egg have been reported to be closer to 75%.Citation67 Such desensitized status is maintained only in a fraction of patients if the food is not ingested daily, and has been reported to be 28% for egg.Citation64,Citation67 The most commonly used OIT protocols are typically divided into three phases requiring ingestion of allergen-specific flour in a food vehicle: 1) initial escalation with six to eight doses of allergen given during day 1 of OIT; 2) build-up dosing under medical observation in a protected environment until a target dose is reached (every 1–2 weeks over 6–12 months); and 3) daily home maintenance dosing (typically years).Citation64 Wheat OIT has been trialed in both a small group of adults and children showing efficacy similar to the one described for milk and egg.Citation64 There are also ongoing clinical OIT for wheat (NCT01980992, and NCT01755884, http://www.clinicaltrial.gov).

The major limitation of widespread use of OIT is due to safety concerns.Citation64,Citation68 All OIT protocols are associated with significant side effects with almost 10% of the treated patients experienced a systemic reaction requiring epinephrine, in addition only 60%–90% were able to achieve the final maximum dose and only 25%–50% maintained tolerance after 2–4 years of therapy. Therefore, in the USA, it is still not recommended for regular clinical care at present.Citation64 Up to 10% of patients undergoing OIT develop eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) when the particular food is reintroduced into the diet.Citation64

With SLIT, patients take a dose of allergen as an extract which is placed under the tongue and then either spat out or swallowed. It has been successfully used for the treatment of asthma and allergic rhinitis. SLIT is not currently recommended for treatment of a food allergy, but it has been successful in causing desensitization to food allergens in clinical trials.Citation64 The main advantage of SLIT is its favorable safety profile, and the main disadvantage is its lower efficacy compared to OIT.Citation64 There has been no studies published so far on the use of SLIT for a wheat allergy.

EPIT uses a skin patch to deliver allergen to the patient. Preclinical trials for peanuts and milk have shown promising results.Citation64,Citation69,Citation70 There is currently no wheat trail underway (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) nor have any been published.

Management of WDEIA includes prompt treatment with epinephrine during an acute episode.Citation15 To prevent WDEIA, the following strategies are recommended: 1) avoidance of exercise within 4–6 hours following wheat ingestion; 2) avoidance of exercising alone or in hot or humid weather, or during pollen allergy season; and 3) always carrying emergency medication.Citation15 Once WDEIA occurs, it needs to be treated like a wheat induced anaphylaxis.

For baker’s asthma and allergic rhinitis, like for many occupational related diseases, strict avoidance of occupational triggers, such as grain flours, remains the primary step in the management of the disease.Citation18 However, as it has been done for other occupational agents such as latex, specific immunological treatments can become therapeutic options for baker’s asthma. Standard subcutaneous immunotherapy has been reported to be effective in a few case series in Baker’s asthma.Citation71–Citation73 However, the US Food and Drug Administration does not recommend injection therapy with food extracts.Citation74 Also the use of omalizumab (anti-IgE monoclonal antibody) may represent a possible treatment in very selected cases of an occupational allergy, as well as an approach to reduce side effects of immunotherapy.Citation75

Non-IgE mediated food allergies

Epidemiology

Wheat can cause a non-IgE mediated allergic disorder by inducing a Th2 lymphocytic response largely independent from IgE-specific antibodies to wheat (non-IgE mediated inflammation). The vast majority of these responses are characterized by an eosinophilic infiltration in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and are called eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs).Citation76,Citation77 Based on clinical characteristics, pathogenesis, and response to therapy, EGID can be divided into four principal groups: EoE, EG, eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE), and eosinophilic colitis (EC).Citation76–Citation78 Wheat has been found to be an important trigger of EoE and EG but not for EGE and EC and therefore, will not be reviewed in the current review.Citation76–Citation78

EoE is the most common type of EGID, with an incidence rate estimated to be similar to Crohn’s disease (ie, 1/2,000) and it disproportionately affects Caucasian atopic males.Citation79–Citation82 EoE is characterized by pathological eosinophilia limited to the esophagus and driven, in the vast majority of cases, by an allergic response to foods.Citation83,Citation84 EoE is diagnosed when:

there are signs of esophageal dysfunction (ie, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], vomiting, abdominal pain, dysphagia, and food impaction), and is not responsive to maximal proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, and

an esophageal biopsy shows more than 15 eosinophil per high power field (eos/hpf).Citation85

EG together with EGE and EC is part of a group of very rare, ill-defined diseases characterized by eosinophilia and limited to the GI (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, ileus, and colon)Citation42,Citation77,Citation78 and a diagnosis of exclusion after other more common causes of eosinophilia have been ruled out (ie, parasitic infections, drug allergy, and inflammatory diseases associated to GI eosinophilia such as inflammatory bowel disease, Churg–Strauss syndrome, and lupus).Citation77,Citation78

EG is estimated to affect 6.3/100,000 of the general population and is more prevalent in adults than in children.Citation86 EG like EoE, is characterized by tissue eosinophilic inflammation, peripheral eosinophilia, coexisting allergic diseases (eg, allergic rhinitis and/or asthma), and sensitization to multiple food allergens. Also, EG, like EoE, is more prevalent in males.Citation87–Citation89

Pathogenesis

EoE is a food allergy driven atopic disease characterized by Th2 inflammation and limited to the esophagus.Citation83,Citation90–Citation95 Esophageal epithelial cell dysfunction is likely to start the inflammatory process in genetically predisposed individuals.Citation91,Citation94–Citation100

Several independent groups have demonstrated that Th2 cytokines like IL-13, IL-5, and IL-4 cause the inflammation, eosinophilia, and fibrotic changes observed in EoE. However, such Th2 cytokines appear to have redundant effects, as treatment strategies that target a single cytokine (ie, anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-13 antibodies) have not been able to completely control and treat EoE.Citation101 Similarly eosinophils seem to be a marker of Th2 inflammation and not pathogenetic, as anti-IL5 effectively reduces eosinophil infiltration without abolishing EoE esophageal inflammation, fibrosis, and related clinical symptoms.Citation101

Unlike in IgE mediated allergic reactions in EoE, the Th2 inflammation appears to be driven by a dysfunctional epithelium. More specifically, thymic stromal lymphopoietin produced by the esophageal epithelium in genetically predisposed individuals could be one of the major initial driver of the Th2 inflammation in EoE.Citation52,Citation93,Citation95 Furthermore, the epithelial barrier dysfunction described in patients with EoECitation102 could be responsible for enhanced access of food allergens and consequently local sensitization to food allergens in the presence of Th2 inflammation, leading to a chronic food allergy driven inflammation.

Like in any other atopic disease, the vast majority of cases of EoE are triggered by allergens. Specifically in most children and adults, particular foods have been identified as the trigger of EoE Th2 inflammation with a largely non-IgE mediated mechanism.Citation53,Citation83,Citation103,Citation104 Testing for a food allergy by SPT or specific sIgE has not been proven successful in definitive identification of causative foods in EoE, despite the efficacy of targeted food diets in the treatment of EoE.Citation105 Limited clinical trials have also shown that anti-IgE therapy with omalizumab has no effect on esophageal eosinophilia.Citation106 OIT is associated with the development of EoE in 2%–10% of desensitized patients.Citation107,Citation108

The most common food allergens responsible for EoE in both children and adults are milk and wheat.Citation53,Citation83,Citation105,Citation109 Spergel et alCitation105 found that wheat was the definitive cause of EoE in 12% of children and therefore, it was the second most common causative food after milk. Gonsalves et alCitation110 and Molina-Infante et alCitation111 found that in adult patients wheat was the most common causative food as it was triggered 60% and 31% of the time, respectively. No specific allergen of wheat has been determined as a trigger of EoE.Citation112 SPT and the measurement of sIgE for wheat have shown no utility in predicting which patients will respond to a wheat elimination diet.Citation105,Citation110,Citation111

The inflammation present in EG, the patients clinical characteristics, and the response to treatment (ie, Th2 inflammation, male predominance, and response to diet and steroid treatment) are very similar to the one found in EoE, however, genome-wide transcript profiling has shown a distinct signature of EG compared to EoE with only 7% of EG patients having a transcriptome that overlapped with EoE patients. EG is therefore a different disease than EoE being more systemic and is associated with high levels of blood/GI eosinophilia and Th2 immunity.Citation87 EG have been shown to be triggered by foods (including wheat), however, data on the role of food allergens in EG pathogenesis are scarce, because the disease is quite rare. Ko et al demonstrated that 82% of children with EG had resolution after the implementation of an elimination diet that excluded either wheat alone or with other major allergens such as milk, soy, egg, peanuts, and nuts.Citation88

Diagnosis

EoE is a clinicopathological diagnosis and is suspected if patients present symptoms of a dysfunctional, inflamed, and/or fibrotic esophagus. The typical EoE symptoms, such as dysphagia and food impaction, are due to esophageal fibrosis and are more frequent in older children and adults. Infants and young children tend to present more aspecific symptoms of esophageal dysmotility such as gagging, failure to progress in solid introduction and to thrive, and abdominal pain/vomiting and therefore their diagnosis may be missed for a long time.Citation113–Citation115 When suspected, EoE is diagnosed by finding at least 15 eos/hpf in one esophageal biopsy obtained with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Symptoms and biopsy findings in EoE can be very similar to findings in GERD, but differs in that they are typically not responsive to a maximal dose of PPI, and therefore, the diagnostic EGD should be done after at least 8 weeks of the maximum PPI dose.Citation113–Citation116

The diagnosis of which food causes EoE is not so easy. An IgE measurement for specific foods, either via SPT or specific sIgE detection, has little sensitivity and specificity, especially for the two most common triggers of EoE, milk and wheat.Citation105 Even if the association of SPT with atopy patch test increased the sensitivity and specificity of food allergy testing,Citation83 an elimination diet followed after 8 weeks by an EGD remain the gold standard to evaluate the importance of a food allergen in EoE pathogenesis. Trials in which microarray allergens were used to guide the diet have been terminated as most patients failed the diet.Citation63

Symptoms of EG are characterized by abdominal pain and bloating. Patients with a prominent gastric inflammation have nausea, vomiting, and early satiety. On the other hand, patients with prominent duodenal inflammation have malabsorption and protein losing enteropathy. Many patients can have both duodenal and gastric symptoms. If eosinophils involves the muscularis layer of the duodenum or stomach, there can be severe complications such as GI obstruction or GI perforation.Citation89 EG is diagnosed when clinical symptoms suggestive of EG are corroborated by a positive biopsy showing eosinophilic inflammation. Biopsies should be obtained from five–six sites per affected segment (eg, stomach and duodenum), and 30 eos/hpf in the stomach and 50 eos/hpf in the duodenum are generally considered diagnostic.Citation89 Peripheral eosinophilia (>300 eos/mm3) is common, but rarely is it moderate to severe (300–1,500 eos/mm3).Citation89 Food allergy testing such as for EoE, is not sensitive or specific enough to guide the diet.

Treatment

The current clinically-accepted EoE management is similar to other atopic diseases and is based on allergen avoidance and corticosteroid use. Future treatments will probably rely on the induction of antigen tolerance and specific biological treatments.

Steroid treatment for an IgE mediated food allergy is a very effective treatment of EoE. Oral steroids are an effective short term treatment but they cannot be used as a long term therapy because of well-known side effects.Citation117 Swallowed or inhaled corticosteroids (ie, viscous budesonide and Flovent) are effective and well tolerated “topical” treatments.Citation118,Citation119

Particular foods are known to trigger EoE in adults and children.Citation109 There are three accepted dietary approaches that can be used to treat EoE: 1) an elemental diet (effective in virtually all patients) that is based on the ingestion of only elemental formulas, 2) specific antigen avoidance based on allergy testing and/or diet history, and 3) empiric food elimination based on the most common food antigens (also known as six-food elimination diet in which milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanuts/tree nuts, and fish/shellfish are eliminated).Citation85,Citation120

It is very unlikely that OIT will work for EoE. Indeed one of the major side effects of OIT is the induction of EoE.Citation64,Citation107,Citation108,Citation121 Immunotherapeutic approaches that bypass the esophagus, such as EPIT, may be used in the future.

In both pediatric and adult patients with an EG diet (both elemental and six-food elimination diet), it has been reported to be effective in the majority of pediatric patients.Citation88 However, diet alone is rarely an effective treatment as symptoms are severe and need steroids to quickly curb them. Therefore, most patients are treated initially with systemic steroids (0.5–1 mg/kg/day for 5–14 days) followed by a slow tapering off over several weeks (2–4 weeks). Once remission is achieved, long term therapy can be done with diet or with the use of topical or oral steroids. Swallowed budesonide is well studied in EG and has low oral bioavailability.Citation122 Entocort® budesonide capsules (typically 9 mg once daily) need to be opened to crush the contents into a powder, which then is dissolved in 15–30 mL of water and juice.Citation122 Swallowed fluticasone has been used to decrease gastric eosinophils.Citation123

Conclusion

Wheat can cause IgE mediated and non-IgE mediated allergic reactions. IgE mediated reactions can occur from either ingestion (food allergy) or inhalation (occupational allergy) of wheat. A food allergy is more commonly found in children than in adults and can be associated with severe reactions such as anaphylaxis and WDEIA. A food allergy diagnosis is based on detecting a combination of specific IgE to wheat via SPT or sIgE measurement and OFC in a person. Treatment for a food allergy at present is based on either avoidance of wheat altogether, or if ingested, then emergency lifesaving self-injectable epinephrine can be used. However, in the near future immunotherapy (OIT, SLIT, and EPIT) may represent a valid way to treat the disease.

Respiratory IgE mediated wheat allergy can cause baker’s asthma and rhinitis, a common occupational disease in bakers and workers with significant repetitive contact to wheat flour. Diagnosis is based on a combination of detection of specific IgE to wheat and inhalation wheat challenges. Treatment is based on avoidance. In the near future immunotherapy (OIT, SLIT, and EPIT) may represent a valid way to treat the disease.

Non-IgE mediated food allergies to wheat are mainly EoE and EG. EoE is an increasingly recognized food allergy that affects mainly Caucasian, atopic males. Wheat is one of the major triggers of the disease and diagnosis is based on the presence of at least 15 eos/hpf in one esophageal biopsy after 8 weeks of PPI treatment. Diagnosis of a food allergy is based on a food elimination diet followed by an EGD which shows a resolution of the disease. EG is a rare disease that is associated with severe symptoms which needs prompt treatment with oral steroids followed by an elimination diet in an attempt to maintain such remission. Measurement of specific IgE to wheat is not a valuable tool to decide if wheat triggers EG.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FasanoASaponeAZevallosVSchuppanDNonceliac gluten sensitivityGastroenterology201514861195120425583468

- CianferoniASpergelJMFood allergy: review, classification and diagnosisAllergol Int200958445746619847094

- CianferoniAKhullarKSaltzmanROral food challenge to wheat: a near-fatal anaphylaxis and review of 93 food challenges in childrenWorld Allergy Organ J2013611423965733

- CianferoniAMuraroAFood-induced anaphylaxisImmunol Allergy Clin North Am201232116519522244239

- SalcedoGQuirceSDiaz-PeralesAWheat allergens associated with Baker’s asthmaJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol20112128192

- NovembreECianferoniABernardiniREpidemiology of insect venom sensitivity in children and its correlation to clinical and atopic featuresClin Exp Allergy19982878348389720817

- PooleJABarrigaKLeungDYTiming of initial exposure to cereal grains and the risk of wheat allergyPediatrics200611762175218216740862

- VenterCPereiraBGrundyJClaytonCBArshadSHDeanTPrevalence of sensitization reported and objectively assessed food hypersensitivity amongst six-year-old children: a population-based studyPediatr Allergy Immunol200617535636316846454

- VenterCPereiraBGrundyJIncidence of parentally reported and clinically diagnosed food hypersensitivity in the first year of lifeJ Allergy Clin Immunol200611751118112416675341

- VenterCPereiraBVoigtKComparison of open and double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges in diagnosis of food hypersensitivity amongst childrenJ Hum Nutr Diet200720656557918001378

- VenterCPereiraBVoigtKPrevalence and cumulative incidence of food hypersensitivity in the first 3 years of lifeAllergy200863335435918053008

- KeetCAMatsuiECDhillonGLenehanPPaterakisMWoodRAThe natural history of wheat allergyAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2009102541041519492663

- AiharaYKotoyoriTTakahashiYOsunaHOhnumaSIkezawaZThe necessity for dual food intake to provoke food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FEIAn): a case report of FEIAn with simultaneous intake of wheat and umeboshiJ Allergy Clin Immunol200110761100110511398092

- PourpakZGhojezadehLMansouriMMozaffariHFarhoudiAWheat anaphylaxis in childrenImmunol Invest200736217518217365018

- ScherfKABrockowKBiedermannTKoehlerPWieserHWheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxisClin Exp Allergy Epub2015918

- Du ToitGFood-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis in childhoodPediatr Allergy Immunol200718545546317617816

- WiszniewskaMNowakowska-SwirtaEPalczynskiCWalusiak-SkorupaJDiagnosing of bakers’ respiratory allergy: is specific inhalation challenge test essential?Allergy Asthma Proc201132211111821439164

- QuirceSDiaz-PeralesADiagnosis and management of grain-induced asthmaAllergy Asthma Immunol Res20135634835624179680

- SampsonHAFood allergy. Part 1: immunopathogenesis and clinical disordersJ Allergy Clin Immunol19991035 Pt 171772810329801

- LeeLABurksAWFood allergies: prevalence, molecular characterization, and treatment/prevention strategiesAnnu Rev Nutr20062653956516602930

- ChehadeMMayerLOral tolerance and its relation to food hypersensitivitiesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2005115131215637539

- HeymanMSymposium on ‘dietary influences on mucosal immunity’. How dietary antigens access the mucosal immune systemProc Nutr Soc200160441942612069393

- IwasakiAMucosal dendritic cellsAnnu Rev Immunol20072538141817378762

- DahanSRoth-WalterFArnaboldiPAgarwalSMayerLEpithelia: lymphocyte interactions in the gutImmunol Rev200721524325317291293

- MowatAMAnatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigensNat Rev Immunol20033433134112669023

- LackGEpidemiologic risks for food allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812161331133618539191

- RomagnaniPAnnunziatoFPiccinniMPMaggiERomagnaniSTh1/Th2 cells, their associated molecules and role in pathophysiologyEur Cytokine Netw200011351051111203198

- RadauerCBreitenederHEvolutionary biology of plant food allergensJ Allergy Clin Immunol2007120351852517689599

- PastorelloEAFarioliLContiAWheat IgE-mediated food allergy in European patients: alpha-amylase inhibitors, lipid transfer proteins and low-molecular-weight glutenins. Allergenic molecules recognized by double-blind, placebo-controlled food challengeInt Arch Allergy Immunol20071441102217496422

- PalosuoKAleniusHVarjonenEA novel wheat gliadin as a cause of exercise-induced anaphylaxisJ Allergy Clin Immunol19991035 Pt 191291710329828

- MoritaEMatsuoHMiharaSMorimotoKSavageAWTathamASFast omega-gliadin is a major allergen in wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxisJ Dermatol Sci20033329910414581135

- PahrSSelbRWeberMBiochemical, biophysical and IgE-epitope characterization of the wheat food allergen, Tri a 37PloS one2014911e11148325368998

- PahrSConstantinCPapadopoulosNGalpha-Purothionin, a new wheat allergen associated with severe allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201313241000100323810762

- PahrSConstantinCMariAMolecular characterization of wheat allergens specifically recognized by patients suffering from wheat-induced respiratory allergyClin Exp Allergy201242459760922417217

- PalacinAQuirceSArmentiaAWheat lipid transfer protein is a major allergen associated with baker’s asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol200712051132113817716720

- PastorelloEAFarioliLStafylarakiCWheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis caused by a lipid transfer protein and not by omega-5 gliadinAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2014112438638724507829

- Sánchez-MongeRGarcía-CasadoGLópez-OtínCArmentiaASalcedoGWheat flour peroxidase is a prominent allergen associated with baker’s asthmaClin Exp Allergy19972710113011379383252

- YamashitaHNanbaYOnishiMKimotoMHiemoriMTsujiHIdentification of a wheat allergen, Tri a Bd 36K, as a peroxidaseBiosci Biotechnol Biochem200266112487249012506994

- KobrehelKWongJHBaloghAKissFYeeBCBuchananBBSpecific reduction of wheat storage proteins by thioredoxin hPlant Physiol199299391992411538180

- WeichelMGlaserAGBallmer-WeberBKSchmid-GrendelmeierPCrameriRWheat and maize thioredoxins: a novel cross-reactive cereal allergen family related to baker’s asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2006117367668116522470

- WeichelMVergoossenNJBonomiSScreening the allergenic repertoires of wheat and maize with sera from double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge positive patientsAllergy200661112813516364168

- ConstantinCQuirceSGroteMMolecular and immunological characterization of a wheat serine proteinase inhibitor as a novel allergen in baker’s asthmaJ Immunol2008180117451746018490745

- ConstantinCQuirceSPoorafsharMMicro-arrayed wheat seed and grass pollen allergens for component-resolved diagnosisAllergy20096471030103719210348

- LehtoMAiraksinenLPuustinenAThaumatin-like protein and baker’s respiratory allergyAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2010104213914620306817

- BittnerCGrassauBFrenzelKBaurXIdentification of wheat gliadins as an allergen family related to baker’s asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008121374474918036646

- SanderIRaulf-HeimsothMDuserMFlaggeACzupponABBaurXDifferentiation between cosensitization and cross-reactivity in wheat flour and grass pollen-sensitized subjectsInt Arch Allergy Immunol199711243783859104794

- JonesSMMagnolfiCFCookeSKSampsonHAImmunologic cross-reactivity among cereal grains and grasses in children with food hypersensitivityJ Allergy Clin Immunol19959633413517560636

- NiggemannBSielaffBBeyerKBinderCWahnUOutcome of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge tests in 107 children with atopic dermatitisClin Exp Allergy1999291919610051707

- NiggemannBRolinck-WerninghausCMehlABinderCZiegertMBeyerKControlled oral food challenges in children – when indicated, when superfluous?Allergy200560786587015932374

- PerryTTMatsuiECConover-WalkerMKWoodRARisk of oral food challengesJ Allergy Clin Immunol200411451164116815536426

- ReibelSRohrCZiegertMSommerfeldCWahnUNiggemannBWhat safety measures need to be taken in oral food challenges in children?Allergy2000551094094411030374

- SiracusaMCSaenzSAHillDATSLP promotes interleukin-3-independent basophil haematopoiesis and type 2 inflammationNature2011477736322923321841801

- GonsalvesNFood allergies and eosinophilic gastrointestinal illnessGastroenterol Clin North Am20073617591vi17472876

- FujitaHOsunaHKanbaraTInomataNIkezawaZ[Wheat anaphylaxis enhanced by administration of acetylsalicylic acid or by exercise]Arerugi2005541012031207 Japanese16407667

- BrockowKKneisslDValentiniLUsing a gluten oral food challenge protocol to improve diagnosis of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2015135497798425269870

- van KampenVRabsteinSSanderIPrediction of challenge test results by flour-specific IgE and skin prick test in symptomatic bakersAllergy200863789790218588556

- HoubaRHeederikDDoekesGWheat sensitization and work-related symptoms in the baking industry are preventable. An epidemiologic studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981585 Pt 1149915039817699

- HoubaRVan RunPHeederikDDoekesGWheat antigen exposure assessment for epidemiological studies in bakeries using personal dust sampling and inhibition ELISAClin Exp Allergy19962621541638835122

- MeijsterTTielemansEde PaterNHeederikDModelling exposure in flour processing sectors in the Netherlands: a baseline measurement in the context of an intervention programAnn Occup Hyg200751329330417369619

- MergetRHegerMGlobischAQuantitative bronchial challenge tests with wheat flour dust administered by spinhaler: comparison with aqueous wheat flour extract inhalationJ Allergy Clin Immunol199710021992079275141

- SanderIRihsHPDoekesGComponent-resolved diagnosis of baker’s allergy based on specific IgE to recombinant wheat flour proteinsJ Allergy Clin Immunol201513561529153725576081

- OlivieriMBiscardoCAPalazzoPWheat IgE profiling and wheat IgE levels in bakers with allergic occupational phenotypesOccup Environ Med201370961762223685986

- van RhijnBDVlieg-BoerstraBJVersteegSAEvaluation of allergen-microarray-guided dietary intervention as treatment of eosinophilic esophagitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol201513641095109725935104

- JonesSMBurksAWDupontCState of the art on food allergen immunotherapy: oral, sublingual, and epicutaneousJ Allergy Clin Immunol2014133231832324636471

- VarshneyPJonesSMScurlockAMA randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic responseJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011127365466021377034

- SkripakJMNashSDRowleyHA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812261154116018951617

- BurksAWJonesSMWoodRAOral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in childrenN Engl J Med2012367323324322808958

- ThyagarajanAVarshneyPJonesSMPeanut oral immunotherapy (OIT) is not ready for clinical useJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101261313220620564

- KalachNSoulainesPde BoissieuDDupontCA pilot study of the usefulness and safety of a ready-to-use atopy patch test (Diallertest) versus a comparator (Finn Chamber) during cow’s milk allergy in childrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol200511661321132616337466

- DupontCKalachNSoulainesPLegoue-MorillonSPiloquetHBenhamouPHCow’s milk epicutaneous immunotherapy in children: a pilot trial of safety, acceptability, and impact on allergic reactivityJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012551165116720451043

- CrivellaroMSennaGMarcerGPassalacquaGImmunological treatments for occupational allergyInt J Immunopathol Pharmacol201326357958424067454

- ArmentiaAMartin-SantosJMQuinteroABakers’ asthma: prevalence and evaluation of immunotherapy with a wheat flour extractAnn Allergy19906542652722221484

- CirlaAMLorenziniRACirlaPERecupero professionale di panificatiori allergici mediante vaccino verso farina di frumento [Specific immunotherapy and relocation in occupational allergic bakers]Giornale italiano di medicina del lavoro ed ergonomia2007293 Suppl443445 Italian18409768

- ArmentiaAArranzMMartinJMEvaluation of immune complexes after immunotherapy with wheat flour in bakers’ asthmaAnn Allergy19926954414441456487

- OlivieriMBiscardoCATurriSPerbelliniLOmalizumab in persistent severe bakers’ asthmaAllergy200863679079118445199

- DeBrosseCWRothenbergMEAllergy and eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders (EGID)Curr Opin Immunol200820670370818721876

- FurutaGTForbesDBoeyCEosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs)J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200847223423818664881

- StraumannAIdiopathic eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in adultsBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200822348149618492567

- StraumannASimonHUEosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology?J Allergy Clin Immunol2005115241841915696105

- CherianSSmithNMForbesDARapidly increasing prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in Western AustraliaArch Dis Child200691121000100416877474

- van RhijnBDVerheijJSmoutAJBredenoordAJRapidly increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in a large cohortNeurogastroenterol Motil2013251475222963642

- HruzPStraumannABussmannCEscalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, SwitzerlandJ Allergy Clin Immunol201112861349135022019091

- SpergelJMBrown-WhitehornTFBeausoleilJL14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2009481303619172120

- StraumannAEosinophilic esophagitis: a bulk of mysteriesDig Dis20133116923797116

- LiacourasCAFurutaGTHiranoIEosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adultsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011128132021477849

- JensenETMartinCFKappelmanMDDellonESPrevalence of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis: Estimates From a National Administrative DatabaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr Epub2015520

- CaldwellJMCollinsMHStuckeEMHistologic eosinophilic gastritis is a systemic disorder associated with blood and extragastric eosinophilia, TH2 immunity, and a unique gastric transcriptomeJ Allergy Clin Immunol201413451114112425234644

- KoHMMorottiRAYershovOChehadeMEosinophilic gastritis in children: clinicopathological correlation, disease course, and response to therapyAm J Gastroenterol201410981277128524957155

- PrussinCEosinophilic gastroenteritis and related eosinophilic disordersGastroenterol Clin North Am201443231732724813518

- BlanchardCMinglerMKVicarioMIL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoidsJ Allergy Clin Immunol200712061292130018073124

- BlanchardCWangNStringerKFEotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitisJ Clin Invest2006116253654716453027

- JyonouchiSSmithCLSarettaFInvariant natural killer T cells in children with eosinophilic esophagitisClin Exp Allergy2014441586824118614

- NotiMWojnoEDKimBSThymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitisNat Med20131981005101323872715

- SherrillJDGaoPSStuckeEMVariants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010126116016520620568

- RothenbergMESpergelJMSherrillJDCommon variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitisNat Genet201042428929120208534

- KottyanLCDavisBPSherrillJDGenome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic diseaseNat Genet201446889590025017104

- NoelRJPutnamPERothenbergMEEosinophilic esophagitisN Engl J Med2004351994094115329438

- SherrillJDRothenbergMEGenetic and epigenetic underpinnings of eosinophilic esophagitisGastroenterol Clin North Am201443226928024813515

- FranciosiJPTamVLiacourasCASpergelJMA case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20097441541919118642

- SleimanPMWangMLCianferoniAGWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis lociNat Commun20145559325407941

- SpergelJMRothenbergMECollinsMHReslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012129245646322206777

- SherrillJDKcKWuDDesmoglein-1 regulates esophageal epithelial barrier function and immune responses in eosinophilic esophagitisMucosal immunology20147371872924220297

- KellyKJLazenbyAJRowePCYardleyJHPermanJASampsonHAEosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formulaGastroenterology19951095150315127557132

- KagalwallaAFSentongoTARitzSEffect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2006491097110216860614

- SpergelJMBrown-WhitehornTFCianferoniAIdentification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination dietJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130246146722743304

- ClaytonFFangJCGleichGJEosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgEGastroenterology2014147360260924907494

- LucendoAJAriasATeniasJMRelation between eosinophilic esophagitis and oral immunotherapy for food allergy: a systematic review with meta-analysisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2014113662462925216976

- MaggadottirSMHillDARuymannKResolution of acute IgE-mediated allergy with development of eosinophilic esophagitis triggered by the same foodJ Allergy Clin Immunol201413351487148924636092

- SpergelJMEosinophilic esophagitis in adults and children: evidence for a food allergy component in many patientsCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20077327427817489048

- GonsalvesNYangGYDoerflerBRitzSDittoAMHiranoIElimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factorsGastroenterology201214271451145922391333

- Molina-InfanteJAriasABarrioJRodriguez-SanchezJSanchez-CazalillaMLucendoAJFour-food group elimination diet for adult eosinophilic esophagitis: A prospective multicenter studyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201413451093109925174868

- ErwinEATripathiAOgboguPUIgE Antibody Detection and Component Analysis in Patients with Eosinophilic EsophagitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract Epub2015619

- FurutaGTLiacourasCACollinsMHEosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatmentGastroenterology200713341342136317919504

- Menard-KatcherPMarksKLLiacourasCASpergelJMYangYXFalkGWThe natural history of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the transition from childhood to adulthoodAliment Pharmacol Ther201337111412123121227

- MervesJMuirAModayur ChandramouleeswaranPCianferoniAWangMLSpergelJMEosinophilic esophagitisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2014112539740324566295

- LiacourasCASpergelJGoberLMEosinophilic esophagitis: clinical presentation in childrenGastroenterol Clin North Am201443221922924813511

- LiacourasCASpergelJMRuchelliEEosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 childrenClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20053121198120616361045

- AcevesSSBastianJFNewburyRODohilROral viscous budesonide: a potential new therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in childrenAm J Gastroenterol2007102102271227917581266

- ButzBKWenTGleichGJEfficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitisGastroenterology2014147232433324768678

- GreenhawtMAcevesSSSpergelJMRothenbergMEThe management of eosinophilic esophagitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract20131433234024565538

- Sanchez-GarciaSRodriguez Del RioPEscuderoCMartinez-GomezMJIbanezMDPossible eosinophilic esophagitis induced by milk oral immunotherapyJ Allergy Clin Immunol201212941155115722236725

- TanACKruimelJWNaberTHEosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with non-enteric-coated budesonide tabletsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200113442542711338074

- AmmouryRFRosenmanMBRoettcherDGuptaSKIncidental gastric eosinophils in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: do they matter?J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201051672372620601904

- PalosuoKVarjonenEKekkiOMWheat omega-5 gliadin is a major allergen in children with immediate allergy to ingested wheatJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108463463811590393

- EbisawaMShibataRSatoSBorresMPItoKClinical utility of IgE antibodies to omega-5 gliadin in the diagnosis of wheat allergy: a pediatric multicenter challenge studyInt Arch Allergy Immunol20121581717622212744

- SampsonHAUtility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001107589189611344358

- MatsuoHDahlstromJTanakaASensitivity and specificity of recombinant omega-5 gliadin-specific IgE measurement for the diagnosis of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxisAllergy200863223323618186814