Abstract

We report here on a 60-year-old male with alcohol-related macrocytic anemia. He was hospitalized on three occasions with hemoglobin < 9.0 g/dL and mean corpuscular volume > 130 fL. Careful history taking and observation of his blood status led us to make a correct diagnosis. At the time of each of his admissions, only with bed rest and abstinence from alcohol did our patient dramatically show spontaneous recovery of anemia in association with a rapid decline of serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase values. It is well recognized that marrow abnormalities in alcoholic patients are reversible. Physicians should be aware that there is a subset of patients with macrocytic anemia that could be improved without medication.

Introduction

Various causes are known to result in macrocytic anemia, consisting of megaloblastic or nonmegaloblastic types. A synthetic DNA problem is responsible for megaloblastic pernicious anemia, most often due to folate/vitamin B12 deficiency, poisonous toxins, or chemotherapeutic agents. Red cell membrane disease as well as myelodysplasia needs to be differentiated. In addition, chronic alcoholism should also be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of macrocytic anemia, particularly in adults.Citation1,Citation2 Megaloblastic anemia with ringed sideroblasts is a well-recognized entity in alcohol abusers.Citation3,Citation4 In anemia in alcoholics, two mechanisms are suggested – one is the development of megaloblastic hematopoiesis by induction of folate deficiency, and the other is nonmegaloblastic-type macrocytic anemia due to the direct toxic effect of alcohol on erythroid precursors independent of folate depletion.Citation3 These marrow abnormalities in alcoholic patients are known to be reversible.Citation3–Citation5 We report here a case of alcohol-related macrocytic but nonmegaloblastic anemia, which spontaneously resolved without any treatment besides bed rest and abstinence from alcohol, confirmed on three occasions of his hospital admissions.

Case report

The patient, a 60-year-old male, was hospitalized three times because of macrocytic anemia (mean corpuscular volume [MCV] >130 fL), first from December 2007 to January 2008 for thoracic compression fracture, when it was first noticed that he was anemic. His second admission was for evaluation of the causes of his anemia, from December 2008 to January 2009, when his anemia was diagnosed as alcohol-related macrocytic/sideroblastic anemia. He was admitted a third time, in November 2009, because of fatigue, where he was found to be anemic again. Although we noted his alcohol habit of three to four cups of diluted syochu every day at home, he did not show acute intoxication or any withdrawal symptoms. At first we attempted vitamin B6 administration without success. On his second admission, we performed various studies. The patient (178 cm tall and weighing 60 kg) was anemic but not icteric, with blood pressure 120/78 mmHg and pulse rate 88/min. Lymph adenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly were not noted. Laboratory data were as follows: white blood cell count 2100/μL, red blood cell count 1.70 × 106/μL, hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, MCV 134 fL (reference values 81–100 fL), platelet count 156 × 103/μL, aspartate-aminotransferase 85 IU/L, alanine-aminotransferase 55 IU/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) 223 IU/L (12–49 IU/L), total protein 6.3 g/dL, albumin 3.9 g/dL, and C-reactive protein 0.03 mg/dL. He was negative for hepatitis A, B, and C. Other data showed serum iron 212 μg/dL (<200 μg/dL), total iron-binding capacity 214 μg/dL (246–409 μg/dL), unsaturated iron-binding capacity 14 μg/dL (137–317 μg/dL), ferritin 2640 ng/mL (18.6–261 ng/mL), serum levels of ceruloplasmin 21.3 mg/dL (21–36 mg/dL), copper 92 μg/dL (70–132 μg/dL), zinc 66 μg/dL (64–111 μg/dL), lead 2.8 μg/dL (0–20 μg/dL), serum δ-amino-levulinic acid 1.6 mg/mL (0–2.2 mg/mL), red blood cell-coproporphyrin 33.7 μg/dL, and urinary coproporphyrin 230 μg/g creatinine (<170 μg/g creatinine). Serum levels of vitamin B12 and folate were 364 pg/mL (233–914 pg/mL) and 3.8 ng/mL (3.6–12.9 ng/mL), respectively. He was also noted to have high serum hyaluronic acid 260 ng/mL (<50.0 ng/mL) and type IV collagen 223 ng/mL (<150 ng/mL). Bone marrow smear was moderately cellular with an myeloid/erythriod ratio of 0.4. No megaloblastic changes were noted. Smears showed various red blood cells consisting of macrocytosis, anisocytosis, and poikilocytosis, with Howell-Jolly bodies and punctuate basohilia. Erythroid precursors had multinucleated cells, bizarre nuclei, and basophilic stipplings. Type III sideroblasts accounted for 33%, but ringed sideroblasts were <3%. Chromosome analysis showed normal karyotype.

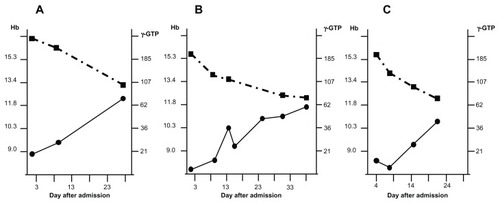

Thus, the patient’s laboratory data showed excess iron accumulation but no deficiencies of vitamin B12 or folate, which are commonly the causes of anemia in alcoholics. On the other hand, he showed significantly elevated serum γ-GTP, which is well recognized in patients with alcoholic liver disease.Citation6 Also, high levels of serum hyaluronic acid and type IV collagen may reflect hepatic fibrosis in alcoholics as liver damage.Citation7,Citation8 As shown in , in all of the three occasions of his hospitalization, without any specific treatment such as supplementation of folate, apart from bed rest and abstinence from alcohol, his anemia improved dramatically in association with a rapid decline of serum γ-GTP values and normalization of MCV over a period of 1 month’s hospital stay on every occasion. As noted in , it was apparent that he was not able to abstain from alcohol once he was discharged from the hospital.

Figure 1 Improvement of anemia and liver dysfunction during hospital stay on three occasions. (A) First admission from December 2007 to January 2008. (B) Second admission from December 2008 to January 2009. (C) Third admission in November 2009.

Discussion

Alcoholism-related anemia shows megaloblastic/sideroblastic changes in the bone marrow, which are known to be reversible.Citation3,Citation4 In the differential diagnosis of macrocytic anemia in our case, we ruled out lead intoxication, anemia derived from copper deficiency due to excess uptake of zinc supplements, myelodysplasia, and abnormal iron metabolism. In our patient, the macrocytic anemia did not respond to vitamin B6 administration but improved only with bed rest and abstinence from alcohol within a month of hospital admission. As treatment for alcohol-related anemia, strict abstinence from alcohol is recommended as a measure of prevention of recurrence;Citation9 however, anemia in our patient recurred once he left hospital. In chronic alcoholics with liver disease, serum low levels of folate and high levels of homocysteine are well known.Citation10 In particular, folate deficiency may contribute to the development of macrocytic/megaloblastic anemia and neurological disorders, while hyperhomocysteinemia is thought to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.Citation10 Although anemia in our patient improved without supplementation of folate, in fact, his serum levels of folate were relatively low at 3.6–3.8 ng/mL (normal range 3.6–12.9 ng/mL), which might have contributed to repeat episodes of anemia. Considering such facts and future risks, we now think that he may need supplementation of folate and to be studied for homocysteine metabolism in the long run.

Conclusion

In conclusion, physicians should be aware that there are adult patients with macrocytic anemia that could be improved without medication. However, in alcoholic patients, long-term nutritional care may be required to prevent the repeat of anemic episodes and other risks due to alcohol-induced metabolic disturbances.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Colon-OteroGMenkeDHookCCA practical approach to the differential diagnosis and evaluation of the adult patient with macrocytic anemiaMed Clin North Am1992765815971578958

- KaferleJStrzodaCEEvaluation of macrocytosisAm Fam Physician20097920320819202968

- HinesJDReversible megaloblastic and sideroblastic marrow abnormalities in alcoholic patientsBr J Haematol196916871015795216

- SavageDLindenbaumJAnemia in alcoholicsMedicine (Baltimore)1986653223383747828

- IwamaHIwaseOHayashiSNakanoMToyamaKMacrocytic anemia with anisocytosis due to alcohol abuse and vitamin B6 deficiencyRinsho Ketsueki199839112711309866426

- LuceyMRConnorJTBoyerTDAlcohol consumption by cirrhotic subjects: patterns of use and effects on liver functionAm J Gastroenterol20081031698170618494835

- HahnEWickGPencevDTimplRDistribution of basement membrane proteins in normal and fibrotic human liver: collagen type IV, laminin and fibronectinGut19802163716988303

- ParsianHRahimipourANouriMSerum hyaluronic acid and laminin as biomarkers in liver fibrosisJ Gastrointestin Liver Dis20101916917420593050

- LewisGWiseMPPoyntonCGodkinAA case of persistent anemia and alcohol abuseNat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol2007452152617768397

- BlascoCCaballeríaJDeulofeuRPrevalence and mechanisms of hyperhomocysteinemia in chronic alcoholicsAlcohol Clin Exp Res2005291044104815976531