Abstract

Background

Morbid obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are prevalent diseases associated with impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Research generally indicates that persons with morbid obesity increase their HRQoL following intervention, whereas evidence of increases in HRQoL in persons with COPD is mixed. Examining the patterns of change over time instead of merely examining whether HRQoL changes will add to the knowledge in this field.

Methods

A sample of persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD was recruited from learning and mastery courses and rehabilitation centers in Norway. The data were collected by self-report questionnaires at the start of patient education and at four subsequent time points during the 1-year follow-up. HRQoL was measured with the Short Form 12, version 2, and repeated measures analysis of variance was employed in the statistical analysis.

Results

Participants with morbid obesity linearly increased their physical HRQoL during the 1-year follow-up, whereas participants with COPD showed no change. None of the groups changed their mental HRQoL during follow-up. In all subdomains of HRQoL, the participants with morbid obesity showed favorable, linearly increasing trajectories across the follow-up period. Among the participants with COPD, no change patterns occurred in the subdomains of HRQoL, except for a fluctuating pattern in the mental health domain. Age, sex, and work status did not influence the trajectories of HRQoL in any of the domains.

Conclusion

A more favorable trajectory of HRQoL was found for persons with morbid obesity than for persons with COPD, possibly due to the obese persons’ better chances of recovery.

Background

Morbid obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are chronic illnesses that are becoming increasingly widespread across the world. According to estimates for 2008, 500 million people worldwide are obese, representing >10% of the world’s adult population.Citation1 The prevalence of obesity is particularly high in Western countries: recent estimates for the US are reported as between 26%Citation2 and 36%,Citation3 whereas the corresponding prevalence in Norway is 23%.Citation4 Moreover, the proportion of obese persons classified with morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] >40) appears to be increasing.Citation2 The figures concerning COPD are equally alarming: Sixty-five million people worldwide are estimated to have moderate-to-severe COPD.Citation5 This disease is considered the fifth leading cause of death and is expected to become the third leading cause by 2030.Citation5

Morbid obesity and COPD are diseases associated with “lifestyle”. Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors are important causal factors for both the diseases, most notably physical inactivity, and overeating (morbid obesity) and smoking (COPD). However, the illnesses are markedly dissimilar in terms of how they normally progress. Morbid obesity is considered a serious chronic illness, but its related deaths are usually caused by consequent health problems that can be countered by various means.Citation2 By increasing physical activity and improving the diet, the person can reduce weight and promote health. Further, medication and surgery are commonly used treatments. In contrast, COPD has been perceived a progressive disease. In spite of the palliative nature of COPD treatment, self-management strategies, including regular physical activity and giving up smoking, are important to improve symptom management and reduce or delay exacerbations of the illness. Generally, patient education for persons with chronic illnesses seeks to enhance the person’s understanding of the illness and to change behaviors accordingly. Such changes may differ for persons with morbid obesity compared to persons with COPD, as reflected in studies of illness perceptionsCitation6 and general self-efficacy.Citation7

The knowledge about the development of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in persons with these chronic illnesses is limited. We have not found longitudinal studies of HRQoL that incorporate comparisons of different illness groups. Based on the above-mentioned differences, we assume that the two groups will demonstrate different HRQoL trajectories, but this needs to be examined. In general, these illness groups have lower HRQoL than the general population, matched for age and sex.Citation8–Citation11 Studies indicate that persons with morbid obesity improve their HRQoL after surgical treatment during the first year of follow-up.Citation10,Citation12,Citation13 In a long-term perspective, these changes may at least partly be related to the person’s subsequent weight maintenance.Citation14,Citation15 Rehabilitation for persons with COPD includes a variety of elements, such as patient education, lifestyle change programs, and medication.Citation16–Citation18 However, positive outcomes after rehabilitation appear to be hard to maintain over time.Citation7,Citation19–Citation21

While most longitudinal research has examined change between two time points, we have only identified one study examining HRQoL change patterns in persons with morbid obesity.Citation11 We have not located similar studies of persons with COPD. In the present study, we address these shortcomings. Our sample consists of persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD, which allows for a comparative view of HRQoL change.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore the trajectories of HRQoL in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with COPD during the first year after completion of patient education. We hypothesized that the participants with morbid obesity would demonstrate favorable HRQoL trajectories compared with the participants with COPD, given the changeable nature of obesity compared to the progressive nature of COPD. Furthermore, we explored whether age, sex, and work status influenced the HRQoL trajectories in the two illness groups.

Method

Study design

A prospective longitudinal study was designed to explore changes in HRQoL in persons participating in patient education in Norway and to test several instruments regarding HRQoL, perception of illness, and dimensions of coping with a view to the sensitivity of these instruments, ie, their ability to detect change over time.Citation22 In this sub-study, sociodemographic variables, social support, and data related to HRQoL were included.

Sample and data collection

Patient education is frequently provided to persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD in Norway as a part of public health care. The two groups have different treatment options and different perceived prospects for improving their health condition – morbid obesity can be treated by a variety of means, while COPD is a progressive disease. For these reasons, we selected to examine the quality-of-life trajectories of these groups.

A convenience sample of home-dwelling persons with morbid obesity or COPD, blinded to the purpose of the study, was consecutively recruited during 2009–2010 when starting patient education. All were referred to patient education by a physician. The inclusion of morbidly obese participants required the person to have a BMI of ≥40 kg/m2,Citation23 as this was the target group for the patient education course. The inclusion of participants with COPD required the person to be classified with moderate-to-severe limitation of airflow, representing GOLD stages 2–3.Citation24 For persons in GOLD stage 2, the forced expiratory volume in 1 second is 50%–79% of normal capacity, whereas GOLD stage 3 indicates that the person has 30%–49% of normal capacity. After receiving verbal and written information about the study, all patient education attendants were invited by the project leader (second author) to participate. Data were collected at five time points: before the start of the patient education course, 2 weeks after the course, and at 3, 6, and 12 months of follow-up. Those who consented completed the first set of questionnaires (baseline assessment) in a secluded room on-site on the first day of the patient education course and returned it in a sealed envelope. Participants completed the questionnaires at home and returned them to the researchers by mail at the following assessments.

Out of a total number of 312 course attendants, 242 (77.6%) gave their consent to participate. Persons with missing responses on any of the variables used in the study were excluded from analyses. Following this procedure, 139 participants were excluded due to not having valid scores on all variables at every assessment, leaving a total sample of 103 participants for this study.

Patient education

Patient education for the participants with morbid obesity lasted between 9 and 15 weeks and included ~40 hours with lectures, small group discussion, and work with personalized action plans. Health care professionals in cooperation with previous course participants developed and delivered the course. The approach was grounded in cognitive behavior theory. It emphasized the participants’ work in uncovering hidden resources, strengthening self-concept and social skills, and raising consciousness of lifestyle choices. It covered major subjects that included available treatments and their intended and unintended consequences, necessary lifestyle changes, and subsequent changes in mind and body.Citation22

The patient education for participants with COPD was based on the similar principles as those discussed earlier, whereas the number of educational sessions varied between 20 and 48 hours. However, the COPD courses lasted between 3 and 5 weeks. The combined educational course and subsequent treatment were assumed to help participants improve their understanding of and coping with the illness, promote a healthier lifestyle and thereby improve their HRQoL.

Measures

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was measured with the Norwegian version of the Short Form 12, version 2, a widely used abbreviated form with 12 items extracted from the original SF-36.Citation25 Eight HRQoL subdomains are constructed from the scale (Cronbach’s α coefficients are provided in the parentheses as appropriate): physical functioning (0.82), role physical (0.91), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional (0.89), and mental health (0.69). In addition, physical component summary (PCS) scores (α=0.89) measuring physical health and mental component summary (MCS) scores (α=0.84) measuring mental health are computed.Citation26,Citation27 As bodily pain, general health, vitality, and social functioning are one-item domains, reliability coefficients are not computable. The PCS and MCS scores are based on norm data from the US.Citation26 A score of 50 corresponds with the mean score, and a deviation of 10 corresponds with one standard deviation (SD) in relation to the US-derived standard. Higher scores on PCS, MCS, and each of the subdomains correspond with better HRQoL in the respective domains.

Environmental characteristics

Social support was measured based on participants’ response to one question: “I think I have enough support from people with whom I have a close relationship.” Response categories were on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “totally agree” (1) to “totally disagree” (5). The scores were reversed for analysis so that higher scores indicated more support. This measure was not validated prior to its use in the study.

Sociodemographic background

Data for age (years), sex (male, female), education (≤12 years of formal education, >12 years of formal education), employment (having paid work, no paid work), and relationship status (married/cohabitant, no paired relationship) were collected.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows version 19.Citation28 Group differences were assessed by χ2 test for categorical variables or by t-test for continuous variables. Two-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to assess the trajectories of HRQoL in the sample, using illness group as the between-subject variable. Possible confounding variables were identified from the analysis of group differences regarding sociodemographic variables. In the two-way ANOVA, thus, the analyses further controlled for potential effects from age, sex, and work status. In addition, given that our sample was mixed in terms of participants having opted (n=40) and not opted for bariatric surgery (n=13), we analyzed whether or not this choice affected their HRQoL trajectories during the follow-up period. At each time point, illness group differences regarding physical health, mental health, and each of the HRQoL subdomains were examined with linear regression models controlling for age, sex, and work status.

In the next step, the analyses were repeated for each of the illness groups separately (one-way ANOVA). Regarding effect sizes, Cohen’s d>0.40 was considered moderate and clinically significant,Citation29,Citation30 whereas partial η2=0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 were interpreted as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.Citation30,Citation31 Adjustments for multiple comparisons between time points were made by using the Bonferroni correction. Cronbach’s coefficient α was used to assess the internal consistency of the HRQoL scales. The significance level was P<0.05. All tests were two-tailed.

Ethics

The Norwegian Research Ethics Committee (REK S-08662c 2008/17575) and the Ombudsman of Oslo University Hospital approved of the study. Written informed consent was received from all participants.

Results

Sample characteristics

The attrition analyses showed that the study participants and dropouts were similar at baseline with regard to sex proportions, education level, and work status. The participants lived more often in paired relationship (n=72, 69.9%) than the dropouts (n=77, 55.8%, P=0.03). The participants were also older (M=54.8 years, SD =13.9 years) than the dropouts (M=49.2 years, SD =15.0 years, P<0.01, d=0.39), and had higher HRQoL mental domain score (M=48.2, SD =11.1) than the dropouts (M=43.9, SD =12.7, P<0.01, d=0.36). HRQoL physical domain scores were similar between participants and dropouts.

The HRQoL mental component scores showed a normal distribution in both illness groups across all time points (all Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality not statistically significant). For the participants with morbid obesity, the HRQoL physical component scores showed a changing distribution across time. Scores were skewed toward lower scores at baseline (skewness =0.24, standard error [SE] =0.33), showed a normal distribution by the end of the patient education and at 3 months of follow-up, and were skewed toward higher scores at 6 months (skewness =–0.41, SE =0.33) and 12 months (skewness =–0.90, SE =0.33) of follow-up. For the participants with COPD, the HRQoL physical component scores showed a normal distribution with one exception at 6 months after the patient education, where the COPD sample scores were skewed toward the lower end of the scale (skewness =0.30, SE =0.34).

The sample characteristics at baseline are described in . Participants with morbid obesity were younger and more often in paid work and a larger proportion of them were females than the participants with COPD. Participants with COPD had higher baseline scores on bodily pain and vitality, indicating higher HRQoL in these subdomains, compared to their counterparts with morbid obesity. Controlling for age, sex, and work status in the regression analysis, however, we found that compared to the participants with morbid obesity, participants with COPD had better physical health and HRQoL in the subdomains role physical, bodily pain, general health, and social functioning. Among the participants with morbid obesity, 40 (75.5%) had bariatric surgery during the follow-up period. The reasons among the participants for having or not having bariatric surgery performed are not known.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample at baseline (N=103)

Trajectories of HRQoL components

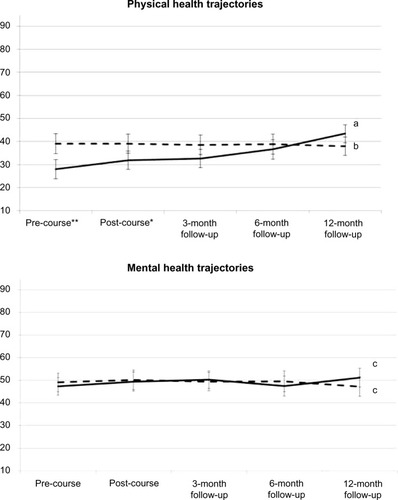

In the total sample, there was a significant interaction effect regarding PCS between time and illness group (Wilks’ lambda =0.64, F [4, 98] =13.80, partial η2=0.36, P<0.001), indicating different PCS trajectories in the two groups. Age, sex, and work status were unrelated to PCS trajectories. Controlling for these factors, the differences between the illness groups remained. Participants with morbid obesity showed a linearly increasing PCS pattern (P<0.001), whereas no change pattern was shown for those with COPD. Regarding the MCS trajectories, there was no difference between the illness groups and no change pattern occurred. Age, sex, and work status were unrelated to MCS trajectories. PCS and MCS trajectories for the study participants, controlling for age, sex, and work status are shown in .

Figure 1 Trajectories of physical health and mental health (HRQoL component scores).

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; CI, confidence interval; PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary.

Considering the PCS trajectories of surgical vs nonsurgical participants with morbid obesity, we found a significant time × illness group interaction with large ES (Wilks’ lambda =0.70, F [4, 48] =5.24, partial η2=0.30, P=0.001), indicating different trajectories in these groups. Subsequent analyses showed linearly increasing PCS with a very large ES in both groups but with a larger ES for those who had undergone surgery during the first year after the patient education course (partial η2=0.74 vs 0.43). The MCS trajectories were not different between surgical and nonsurgical participants in the morbid obesity group (data not shown).

Trajectories of HRQoL subdomains

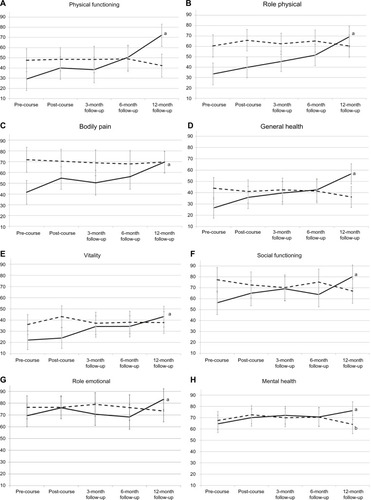

The two illness groups showed differences concerning the trajectories of physical functioning (partial η2=0.32, P<0.001), role physical (partial η2=0.19, P<0.001), bodily pain (partial η2=0.31, P<0.001), general health (partial η2=0.20, P<0.001), vitality (partial η2=0.12, P=0.01), social functioning (partial η2=0.15, P<0.01), and role emotional (partial η2=0.09, P<0.05). Controlling for age, sex, and work status, the different trajectories for the two illness groups remained statistically significant for physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, and social functioning. Group differences concerning the trajectories of vitality reached a borderline level of significance (P=0.06).

When the illness groups were analyzed separately, as shown in , participants in the obesity group showed a linear increase in all HRQoL subdomains: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning (all P<0.001), role emotional (P<0.01), and mental health (P<0.05). Participants with COPD showed a cubic, fluctuating pattern of mental health scores (P<0.05). A borderline significant trend of increasing scores on role physical was shown for this group (P=0.06). Otherwise, no change patterns occurred for any of the other HRQoL subdomains. The participants’ trajectories on the HRQoL subdomains, controlling for age, sex, and work status, are shown in .

Figure 2 Trajectories of the subdomains of HRQoL.

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Participants with morbid obesity demonstrated an improving trajectory of physical health during the following year after participating in a patient education program, while participants with COPD showed no change in physical health. None of the groups showed a change in trajectory regarding mental health during follow-up. In all subdomains of HRQoL, the participants with morbid obesity showed favorable, linearly increasing trajectories across the follow-up period. Participants with COPD showed a fluctuating pattern in the mental health subdomain; otherwise, no change patterns occurred in this group. The participants’ age, sex, and work status did not influence the trajectories of HRQoL in any of the domains.

Trajectories of HRQoL

The trajectory of improving physical health among participants with morbid obesity may have several explanations. They may have implemented a healthier lifestyle with regard to nutrition and physical activity, and thus, have experienced improvements in physical health. Participants who underwent bariatric surgery during the study showed an even stronger improvement in physical health than those without surgery. While recent studies have reported improved HRQoL after bariatric surgery,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation32 our study showed that participants with obesity without bariatric surgery also improved their physical health with a clinically significant ES. The physical health development among these participants may also be due to their very poor physical health condition at baseline, indicating a large potential for improvements.

Only one previous study, following patients for 3 years, has reported HRQoL trajectories in persons with morbid obesity.Citation11 The study found both physical health and mental health to increase markedly during the first 6 months, increase more slowly after 6 months, and stabilize after 1 year. In our study, on the other hand, the PCS scores continued to increase linearly until the 1-year assessment. Unfortunately, we lack the longitudinal data needed to compare our sample with international studies that have continued to assess participants for longer than we did.Citation11,Citation15

HRQoL will stabilize at a certain level at some point in time. However, the time when such stabilization occurs is not predetermined and may result from a variety of factors. Research has found lower HRQoL in persons with morbid obesity 5 years after they had received gastric surgery, compared to general population levels.Citation10 In view of this, further research needs to investigate how one can increase and maintain HRQoL in this group in a long-term perspective.

Participants with COPD did not change their physical health during the 1-year follow-up period. For these participants, the patient education courses had fewer group sessions with discussion and sharing of experiences compared to the courses for the participants with morbid obesity. Given that group discussion and having feedback on personal experience are important ingredients of patient education, differences in course content and organization may contribute to explaining the results.Citation33 In addition, the prospects of health improvement due to treatment and personal efforts (lifestyle change) in persons with COPD are worse, compared to persons with morbid obesity. Studies have found that persons with COPD have mixed results after rehabilitation and have problems maintaining positive changes over time.Citation16,Citation18,Citation34 Our study augments this knowledge by examining the possibility that HRQoL actually may increase after patient education courses but that such increases are reduced to initial levels after some time. For our participants with COPD, no such increase occurred during the first year after the patient education course. More research is needed to explore effective ways of improving and maintaining HRQoL in this group.

None of the groups showed a significant change pattern relating to mental health. This is somewhat surprising, particularly with regard to the participants with morbid obesity. In view of their physical health improvements, one might expect that their mental health would follow a similar pattern. Improvements in mental health have been shown in previous studies of morbid obesity.Citation11,Citation12 However, Laurino Neto and Herbella found a lack of improvement in mental HRQoL and argued that this area might possibly be less affected by obesity.Citation14

As an alternative to the above explanation,Citation14 the participants with morbid obesity may have experienced their life circumstances in the follow-up period to be quite challenging. Regardless of their subsequent treatment (continued lifestyle change, medication, and/or surgery), after having completed the learning and mastery course, they would all have to adjust to and cope with change. Among persons with morbid obesity, many have experienced how easy it is to have goals and ambitions – and just how hard it is to consistently do what it takes to reach these goals.Citation35,Citation36 In such a perspective, the non-changing mental health for this group makes psychological sense, even in the case of physical health improvement.

Generally, the analysis of the HRQoL subdomains for the two groups confirmed the notion of important group differences concerning HRQoL in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with COPD. At the outset of the patient education, participants with COPD had higher HRQoL in the bodily pain and vitality subdomains than the obese participants (and in most of the other subdomains as well, although not reaching statistical significance, ). On the other hand, seven of the eight HRQoL subdomain trajectories were significantly different between the two groups. The participants with morbid obesity showed a linearly increasing pattern of all HRQoL subdomains, whereas the participants with COPD showed a significant change pattern for mental health only. We interpret these results as evidence of morbid obesity being an illness that has a marked negative influence on HRQoL, and apparently, more so than what was the case with COPD. However, the trajectories of HRQoL for the obesity group were positive, as physical health and each of the HRQoL subdomains increased linearly during the first year after the patient education course. In combination, these results indicate that HRQoL may generally be low in persons with morbid obesity, but also that persons with this illness may have good prospects of a positive HRQoL development over time. These results are in line with, but also augment, the positive results from several longitudinal studies of persons with obesity.Citation10–Citation15

Given the lack of similar studies concerning COPD, our study appears to be the first to report on HRQoL trajectories for this group. Our results confer with previous studies reporting poor outcomes after rehabilitation for persons with COPD,Citation16,Citation18,Citation34 and add to the knowledge base by reporting stable (ie, non-improving) trajectories of HRQoL during a 1-year follow-up period. The cubic trajectory found in the mental health subdomain may reflect that emotions are more fluctuating, due to life events and mood variations, than cognitively based functional evaluations. A similar line of reasoning has been put forward recently.Citation37

Study limitations

A small number of participants, the use of a convenience sample, and a relatively short follow-up period are limitations of the study. Skewed distributions may increase the risk of making Type II error. Nonsignificant trajectories were frequent among the participants with COPD, but this group showed a largely normal distribution of SF scores. However, this represents a possibility of Type II error associated with the results for the participants with COPD. The social support measure had not been validated before being used in the study. Future studies should preferably include larger samples, which seem particularly important to increase the reliability of comparisons between subgroups of persons with morbid obesity (ie, surgical treatment vs no surgical treatment for obese participants, and medical treatment vs nonmedical treatment for COPD participants). Differences between participants and dropouts at baseline also limit generalizability. Our study is also limited by not having access to data concerning other relevant health factors, such as comorbidities, duration of illness, progression of illness, and current health-related behaviors (like smoking). For the two groups examined, it would be relevant to measure, for example, BMI, weight, and lung functioning, as changes in these aspects could influence the participants’ HRQoL development over time. However, since the courses were based on a health promotion philosophy, collecting objective health data including weight, height, comorbidities, and disease characteristics would have resulted in that the participants’ attention was directed toward their disease instead of toward making changes in lifestyle. In turn, this shift of attention might have undermined the intervention. Thus, we did not include objective measures in the study. We have not had access to Norwegian norm data for HRQoL as measured with the SF-12. Thus, the norm values for PCS and MCS may be different in the Norwegian population in comparison with the general US population. Future studies should also aim to follow the participants in a longer time perspective, as the long-term outcomes for these groups still appear to be relatively unexplored.

Conclusion

This study found that participants with morbid obesity increased their HRQoL in practically all areas during the 1-year follow-up period after having attended a learning and mastery course. The participants with COPD, contrastingly, showed an increase followed by a subsequent decrease in the mental health subdomains; otherwise, no change patterns were detected for this group. Although a variety of factors could be causing the HRQoL development for the participants, the study has three clinically important implications. For persons with morbid obesity, a condition often associated with reduced HRQoL, HRQoL increased during the 1-year follow-up period. Moreover, it increased in a linear shape, essentially underscoring that positive change can be maintained and strengthened beyond the conclusion of a patient education program. Bearing in mind the results for the participants with COPD, these indicate that persons with this illness may need more extensive and/or more frequent efforts from health professionals to achieve notable changes in HRQoL. This study appears to be the first to examine the trajectories of HRQoL with these illness groups in a comparative perspective, and we conclude that persons with morbid obesity showed more positive trajectories of HRQoL than did persons with COPD.

Authors’ contributions

TB performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. MSF and AL designed the study, interpreted the data, and participated in the revising of the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Norwegian Centre for Patient Education, Research and Service Development, Oslo, Nor-way. The contributions from the following Norwegian institutions are acknowledged: The Patient Education Centers at Oslo University Hospital – Aker, Oslo; Deacon’s Hospital, Oslo; Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital, Oslo; Asker and Bærum Hospital, Sandvika; Østfold Hospital, Sarpsborg; and Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger. In addition, the authors acknowledge the contributions from the following institutions: Pulmonary Rehabilitation Centers at Oslo University Hospital – Ullevål, Oslo; Krokeide Center, Nærland; and Glittreklinikken, Nittedal.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- World Health OrganizationObesity and overweight. Fact sheet #311 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/Accessed June 4, 2014

- BastienMPoirierPLemieuxIDesprésJPOverview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity to cardiovascular diseaseProg Cardiovasc Dis201456436938124438728

- NguyenTLauDCWThe obesity epidemic and its impact on hypertensionCan J Cardiol201228332633322595448

- HolmenJMidthjellKKrokstadSLingaas HolmenTObesity and type 2 diabetes in norway: new data from the HUNT study [abstract]Obesity Facts20092256

- World Health OrganizationBurden of COPD Available from: http://who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/Accessed June 4, 2014

- BonsaksenTLerdalAFagermoenMSTrajectories of illness perceptions in persons with chronic illness: an explorative longitudinal studyJ Health Psychol201520794295324140616

- BonsaksenTFagermoenMSLerdalATrajectories of self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness: an explorative longitudinal studyPsychol Health201429335036424219510

- de ZwaanMPetersenIKaerberMObesity and quality of life: a controlled study of normal-weight and obese individualsPsycho somatics2009505474482

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWThe influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidityJ Clin Epidemiol20035641177118414680668

- HelmiöMSalminenPSintonenHOvaskaJVictorzonMA 5-year prospective quality of life analysis following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesityObes Surg201121101585159121553303

- RobertMDenisABandol-Van StraatenPJaisson-HotIGouillatCProspective longitudinal assessment of change in health-related quality of life after adjustable gastric bandingObes Surg20132310156423515974

- LierHØBiringerEHoveOStubhaugBTangenTQuality of life among patients undergoing bariatric surgery: associations with mental health – a 1 year follow-up study of bariatric surgery patientsHealth Qual Life Outcomes2011917921943381

- AndenæsRFagermoenMSEideHLerdalAChanges in health-related quality of life in people with morbid obesity attending a mearning and mastery course. A longitudinal study with 12-months follow-upHealth Qual Life Outcomes201210951722208808

- Laurino NetoRMHerbellaFAChanges in quality of life after short and long term follow-up of roux-en-y gastric bypass for morbid obesityArq Gastroenterol201350318619024322189

- KolotkinRLDavidsonLECrosbyRDHuntSCAdamsTDSix-year changes in health-related quality of life in gastric bypass patients versus obese comparison groupsSurg Obes Relat Dis20128562563322386053

- BjoernshaveBKorsgaardJJensenCNielsenCVPulmonary rehabilitation in clinical routine: a follow-up studyJ Rehabil Med201345991692323974802

- LabrecqueMRabhiKLaurinCCan a self-management education program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease improve quality of life?Can Respir J2011185e77e8121969935

- ZakrissonABEngfeldtPHägglundDNurse-led multidisciplinary programme for patients with COPD in primary health care: a controlled trialPrim Care Respir J201120442743321687920

- HeppnerPSMorganCKaplanRMRiesALRegular walking and long-term maintenance of outcomes after pulmonary rehabilitationJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2006261445316617228

- RiesALKaplanRMMyersRPrewittLMMaintenance after pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic lung disease: a randomized trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167688088812505859

- MoullecGLaurinCLavoieJMNinotGEffects of pulmonary rehabilitation on quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patientsCurr Opin Pulm Med2011172627121206273

- LerdalAAndenaesRBjornsborgEPersonal factors associated with health-related quality of life in persons with morbid obesity on treatment waiting lists in NorwayQual Life Res20112081187119621336658

- World Health OrganizationGlobal database on body mass index Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jspAccessed March 18, 2010

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease3rd ed Author2011

- LogeJHKaasaSHjermstadMJKvienTKTranslation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validityJ Clin Epidemiol19985111106910769817124

- WareJEKosinskiMATurner-BowkerDMGandekBHow to Score: Version 2 of the SF-12v2 Health SurveyLincoln, RIQualityMetric2005

- WareJEKosinskiMAKellerSDA 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validityMed Care19963432202338628042

- SPSS for Windows, version 220 [computer program]Armonk, NYIBM Corp2013

- CohenJA power primerPsychol Bull1992112115515919565683

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates1988

- PallantJSPSS Survival Manual4th edNew YorkOpen University Press2010

- MaloneMAlger-MayerSPolimeniJMHealth related quality of life after gastric bypass surgeryAppl Res Qual Life201272155161

- NossumRRiseMBSteinsbekkAPatient education – which parts of the content predict impact on coping skills?Scand J Public Health201341442943523474954

- BonsaksenTHaukeland-ParkerSLerdalAFagermoenMSA 1-year follow-up study exploring the associations between perception of illness and health-related quality of life in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis201494150

- BorgeLChristiansenBFagermoenMSMotivation for lifestyle changes among morbidly obese peopleSykepleien Forskning2012711422

- BonsaksenTHustadnesALAxelsenPMBjørnsborgELærer å mestre sykelig fedme [Learning to cope with morbid obesity]Sykepleien20119925860 Norwegian

- MoullecGFavreauHLavoieKLLabrecqueMDoes a self-management education program have the same impact on emotional and functional dimensions of HRQoL?COPD20129364522250666