Abstract

Background: Little data are available about traditional and complementary medicine use in children in the general population in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia. The aim of this investigation was to assess the prevalence of the use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners in children in a national population-based survey in Indonesia.

Methods: The cross-sectional sample included 15,739 children (0–14 years) (median age 7.0 years, inter quartile range =7.0) that took part in the Indonesia Family Life Survey in 2014–2015.

Results: The prevalence of use of traditional medicines as a treatment in the past four weeks was 6.2%, vitamins or supplements 19.9%, and over-the-counter modern medicine 61.1%. The prevalence of traditional practitioner use in the past 4 weeks was 3.4%, and the prevalence of the use of traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioner in the past 4 weeks was 8.8%. The purpose of consulting the traditional practitioner was mainly massage (86.8%) and treatment for illness (14.8%). In the adjusted logistic regression analysis, having a birth certificate (as a proxy for better economic status) and poor self-rated health were associated with traditional medicine use. Younger age and poor self-rated health were associated with traditional practitioners use.

Conclusion: A high prevalence of traditional medicine use in children in Indonesia was found, and several social factors and poor health status of its use were identified.

Introduction

A significant number of people in “Association of Southeast Asian (ASEAN) member states” utilizes traditional health care.Citation1–Citation4 Among adults in Indonesia, “24.4% had used a traditional practitioner and/or traditional medicine in the past four weeks, and 32.9% had used complementary medicine in the past four weeks”.Citation5 There is lack of information on traditional health care among children in the general population,Citation6 including in Indonesia.

One of the most common types of treatment provided by traditional health practitioners in Indonesia was found to be massage for babies (71.4%).Citation7 In a small study of 91 children (6–18 years old) who were admitted to hospital in Indonesia, 39.6% had used Indonesian herbal medicine prior to admission.Citation8 Several investigations have been carried out on the use of traditional medicine for specific acute and chronic conditions, such as fever, diarrhea, and cancer in Indonesia and Malaysia.Citation9–Citation12 Suparmi et al,Citation13,Citation14 have pointed out some of the risks associated with the use of jamu, Indonesian herbal medicines, for the general public, including children, in Indonesia.

The general population prevalence of the past 7 days use of “herbal medicinal products” among children and adolescents (0–17 years) in Germany was 5.8%.Citation6 In the USA less than 0.5% of the children (0–12 years) had used herbal remedies in the past 7 days,Citation15 in Italy 2.4% in the past 3 years (0–13 years).Citation16 The prevalence of past month use of traditional and complementary medicine among children and adolescents (0–18 years) in Taiwan was 4.7%.Citation17 In a study in Germany, herbal medicines were mainly used for treating coughs and colds of children and adolescents.Citation6

Some studies found associations between specific sociodemographic characteristics and traditional and/or complementary medicine use among children and adolescents. For example, younger age,Citation6 female gender,Citation17 and higher socioeconomic status.Citation8,Citation16,Citation17 While in a study in Ethiopia, lower education of the parents was associated with traditional medicine use for children.Citation18 Having a poor health status was also associated with increased use of herbal medicine in Germany.Citation6 The aim of this investigation was to assess the prevalence of the use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners in children in a national population-based survey in Indonesia.

Methods

Study design and participants

Cross-sectional data were analyzed from the child module of the “Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS-5)”, which was conducted in 2014–2015. The IFLS-5 is a household survey representative of 83% of the population in Indonesia, with a survey response rate above 90%; more details on the complex sampling method.Citation19–Citation21 “Two randomly selected children of the head and spouse age 0–14 years” were included per household.Citation19 Questionnaires were administered to the child’s mother, guardian, or caretaker or older sibling if the child was less than 11 years old. “Children between the ages of 11 and 14 were allowed to respond for themselves if they felt comfortable doing so.”Citation19 The IFLS-5 had been approved by the ethics review boards of RAND (“Research ANd Development”) and the University of Gadjah Mada.Citation19–Citation21 Prior to the interview, informed consent was obtained from all the respondents.Citation19–Citation21

Measures

Traditional medicines use

“Now, we’d like to know whether [CHILD’S NAME] has taken medicine on his/her own during the past 4 weeks, namely since […] date, 4 weeks ago?” Response options were “Consumed over-the-counter modern medicines (like bodrexin, inzana, paramex); Consumed traditional herbs or traditional medicines as treatment; Used topical medicines (like eyedrops, cream, medical plaster, ointment and the like); Vitamins/Supplements; Massage, coining, etc.”Citation19

Traditional practitioner use

“In the last 4 weeks, did [CHILD’S NAME] visit a hospital, health center, clinic, doctor’s practice, or a health worker?” Response options were “Public hospital (General or Specialty); Public Health Centre/Auxiliary Centre; Private Hospital; Polyclinic, Private Clinic, Medical Centre; Private Physician (General Practitioner, Specialist, Dentist); Nurse, Paramedic, Midwife practitioner; Traditional practitioner (shaman, wise man, kyai, Chinese herbalist, masseur, acupuncturist, etc.); Other.”Citation19

Last health care provider visit

“Now, I’d like to ask you some questions about [CHILD’S NAME] LAST VISIT to health care providers. What is the type of medical facility or type of provider?”Citation19 Response options as above.

“What was the purpose of [CHILD’S NAME] visit to that facility?”Citation19 Response options “Immunization; Consultation; Medical check-up; Medications; Injection; Treatment for Injury; Treatment for Illness; Massage; Other.”Citation19 (Multiple responses were possible)

“How much did you pay out of pocket for [CHILD’S NAME]’s outpatient care at […] during the past 4 weeks?”Citation19

“Did you use insurance to pay for all or some of this visit?”(Yes, No)Citation19

“What do you think about the services that were provided by this facility?” Response options were “1= Satisfactory, 2= Somewhat satisfactory, 3= Not satisfactory and 4= Far from satisfactory.”Citation19

Socio-demographic factor questions included age, gender, mother’s and father’s education, and having a birth certificate as an indicator of socioeconomic status.Citation19

Self-reported health status was measured with the question, “In general, how is your health?” Response options ranged from 1= Very healthy to 4= Unhealthy.Citation19–Citation21

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and the prevalence of health care utilization. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to calculate the crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals to assess the associations between the independent variables and traditional medicines use and traditional health practitioner use, separately. Age and all other variables that were found statistically significant in univariate analyses were included in the multivariable models. Potential multicollinearity was not detected. P<0.05 was considered significant. “Cross-section analysis weights were applied to match the 2014 Indonesian population”.Citation5,Citation19 All statistical analyses were conducted considering the complex design of the study using STATA software version 13.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample included 15,739 children (0–14 years) (median age 7.0 years, Inter Quartile Range =7.0); 51.5% were male and 48.5% were female, and 17.5% did not have a birth certificate.

Health care utilization

Among seven different health care providers, traditional health practitioners had the fourth highest past 4-weeks prevalence (3.4%), after “nurse, paramedic or midwife practitioners” (6.5%), public health centers (5.7%) and private physician (3.9%). The past 4-weeks prevalence of traditional medicine use as self-treatment was 6.2%, vitamins or supplements 19.9%, and over-the-counter modern medicine 61.1%. The past 4-weeks prevalence of the use of traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioner was 8.8%.

The average expenditure for the past 4-weeks health care provider utilization was lowest for public health centers (10,385 rupiah) and third lowest for traditional practitioners (91,330 rupiah). The average expenditure for the past 4-weeks self-treatment utilization was highest for vitamins or supplements (24,206 rupiah), followed by traditional medicines (10,706 rupiah) and the lowest costs were for massage or coining (6,548 rupiah) (see ).

Table 1 Health care utilization in the past four weeks in 15,739 children (0–14 years)

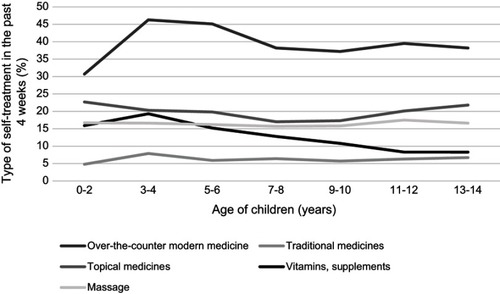

The prevalence of the use of the different self-treatment modalities, including traditional medicines, did not differ much across age groups (see ).

Characteristics of the last health care visit

The purposes of the child’s last health care visit included eight categories, such as immunization and treatment for illness (multiple responses were possible). The purpose of consulting the traditional practitioner was mainly massage (86.8%) and treatment for illness (14.8%). Immunizations were mainly provided by the private hospital (8.2%) and the nurse, paramedic or midwife practitioner (6.3%). Consultations were the highest for the private hospital (16.4%), and medications were the highest for nurse, paramedic or midwife practitioner (64.7%). Medical check-up was the highest in the public hospital (42.0%) ad polyclinic, private clinic or medical center (38.6%). Children were mostly provided an injection by the private physician (18.0%) ad public hospital (12.5%). Treatment for an injury was mainly provided by public and private hospitals (3.4% and 2.5%, respectively). Except for traditional practitioners, all other health care agencies provided above 60% treatment for illness.

Health insurance did not pay for visits to traditional practitioners (0.0%) and only a few for “nurse, paramedic or midwife practitioners” (1.8%) and for almost in half the cases (46.6%) for public hospital visits. Among the last health care service attendees, the highest satisfaction rates were reported for private hospitals (21.3%), followed by traditional health practitioners (19.8%) and private physician (18.3%). Lower health care satisfaction rates were found for public health centers (12.5%) and public hospitals (9.1%) (see ).

Table 2 Characteristics of the last health care provider visit (N=3,109)

Associations with traditional medicine and traditional practitioner use

In the adjusted logistic regression analysis, having a birth certificate (as a proxy for economic status) and poor self-rated health status were associated with traditional medicine use. Younger age and poor self-rated health status were associated with traditional practitioners use (see ).

Table 3 Associations with current traditional and complementary medicine use

Discussion

The study found that in a nationally representative child sample in Indonesia in 2014–15 that the past month prevalence of traditional or herbal medicines use was 6.2%, the past month use of traditional health practitioners was 3.4%, and the past 4-weeks prevalence of the use of traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioners was 8.8%. These general child population prevalences of traditional or herbal and/or complementary medicine use seem higher than found in Italy (2.4% in the past 3 years)Citation16 and USA (0.5% in the past 7 days),Citation13 but similar to Germany (5.8% in the past 7 days),Citation6 and Taiwan (4.7% in the past month).Citation17 The purpose of consulting the traditional practitioner was mainly massage (86.8%) and treatment for illness (14.8%) in this study. This is in agreement with a previous study among adults in Indonesia that indicated that massage for babies (71.4%) was one of the most common traditional treatment types,Citation9 while in a study in Germany, herbal medicines were mainly used for treating coughs and colds of children and adolescents.Citation6 Herbal medicines are available in drug stores without prescription and professional monitoring in Indonesia.Citation8 Parents or guardians should be given health education about herbal medicines and they should also inform health practitioners about the use of herbal medicines of their children in order to prevent negative drug interactions.Citation8 In addition, the producers of herbal medicinal preparations should follow government regulations in producing safe herbal medicines.Citation13,Citation14

The past 4-weeks prevalence of over-the-counter modern medicine use was in this study 61.1% in the past 4 weeks. This result is much higher than in a national survey in children (0–17 years) in Germany, with 25.2% having used self-medication, including 17.0% over-the-counter drugs, in the previous week.Citation23 The very common use of over-the-counter drugs among the child population can be potentially harmful.Citation23 Further research should be conducted on the type of self-medication and indication to assess possible inappropriate drug use.

Consistent with a previous study in Germany,Citation6 this study found that the use of the traditional practitioner decreased with age. One reason for this could be the large proportion of massages administered to babies and small children by traditional practitioners in Indonesia.Citation7,Citation24 However, the use of traditional medicines did not change with age in this study. A previous study found a preponderance of unconventional medicine use among girls in Germany,Citation25 while this study did not find any gender differences in the use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners. This finding is in line with adult use of traditional and complementary medicine in Indonesia.Citation5

Several previous studies in high-income countriesCitation8,Citation17,Citation25 found an association between higher socioeconomic status and traditional and/or complementary medicine use in children. This study also found that having a birth certificate (as a proxy for better economic status) was associated with increased use of traditional medicines. The educational status of the mother and/or father seem not to influence the use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners in children in Indonesia. In agreement with a study in Germany,Citation6 this study also found that having a poor health status was associated with increased use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners in children in Indonesia. One reason for this could be that children with poorer health status, engage in a more frequent and greater variety of health care-seeking behavior, increasing the chances of traditional and/or complementary medicine use.Citation26

In this study, satisfaction (or somewhat satisfied) with the last health care visit with a traditional practitioner was highest (98.6%) compared to other health care provider types. High satisfaction or self-rated improvement of conditions treated with herbal medicinal products was also found in Germany, with 89.2% reporting great or partly improvement of the condition treated.Citation6 In a previous study among adults in Indonesia similar high levels (98.0%) of satisfaction (or somewhat satisfied) with the last health care visit with a traditional practitioner was found.Citation5

In this study, consultation or treatment costs were third lowest for traditional practitioners, after public health centers and polyclinics. Similar results were found among adult health care utilization in Indonesia.Citation6 In this study, the health care costs for the last health care visit were often paid by health insurance for public and private health care (eg, 40.4% for public health centers and 38.5% for private hospitals) but not for treatment by traditional practitioners. This result demonstrates that parents or caretakers are willing to pay a certain amount of money for the treatment by traditional health practitioners in Indonesia.

Study limitations

Although a large population sample was utilized in this survey, data are cross-sectional and therefore no causality can be established. The assessment by self-report may have biased responses. Future studies should assess more details regarding the type of herbal medicines and other treatments in relation to the specific illness or condition of the child.

Conclusions

The study found a high prevalence of traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioner use in Indonesia. Younger age, socioeconomic status, and poor self-rated health status were found to be associated with traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioner use. Health care providers should provide education to patients on traditional medicine use and on ways to combine the use of herbal and biomedical medicine, and producers should provide safe herbal medicines. This study provides a reference on the use of traditional medicines and traditional practitioners for parents, health care providers, and policy-makers. Further research should examine the effectiveness and safety of specific herbal medicinal remedies.

Acknowledgments

RAND is thanked for giving us access to the IFLS-5 data (http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html).

Data availability

Data from the IFLS-5 is available from RAND at http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Ministry of Health. General Secretariat. Indonesia Health Profile 2013. Jakarta: Ministry of Health RI; 2014.

- Chuthaputti A, Boonterm B. Traditional Medicine in ASEAN. Bangkok: Medical Publisher; 2010.

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Utilization and practice of Traditional/Complementary/Alternative Medicine (T/CAM) in Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. Stud Ethno-Med. 2015;9(2):209–218.

- ASEAN Secretariat. Towards harmonization of traditional medicine practices. e-Health Bull. 2012;2:1–8. Available from: www.asean.org/…/asean-e-health-bulletin-towards-harmonisation-of-traditional-medicine-practices. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Utilization of traditional and complementary medicine in Indonesia: results of a national survey in 2014–15. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:156–163. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.00630396615

- Du Y, Wolf I-K, Zhuang W, Bodemann S, Knöss W, Knopf H. Use of herbal medicinal products among children and adolescents in Germany. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:218. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-21824988878

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Traditional health practitioners in Indonesia: their profile, practice and treatment characteristics. Complement Med Res. 2018. doi:10.1159/000494457

- Suryawati, Suard HN. The use of herbal medicine in children. In: Proceedings of The 5 th Annual International Conference Syiah Kuala University (AIC Unsyiah) 2015 In conjunction with The 8 th International Conference of Chemical Engineering on Science and Applications (ChESA 2015); 9 9–11, 2015; Banda Aceh, Indonesia Available from: https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/173212-EN-the-use-of-herbal-medicine-in-children.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Maulida TF, Wanda D. The utilization of traditional medicine to treat fever in children in western Javanese culture. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2017;40(sup1):161–168. doi:10.1080/24694193.2017.138698529166189

- Chandra KA, Wanda D. Traditional method of initial diarrhea treatment in children. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2017;40(sup1):128–136. doi:10.1080/24694193.2017.138698029166193

- Susilawati D, Sitaresmi M, Handayani K, et al. Healthcare providers’ and parents’ perspectives on complementary alternative medicine in children with cancer in Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(7):3235–3242.27509956

- Hamidah A, Rustam ZA, Tamil AM, Zarina LA, Zulkifli ZS, Jamal R. Prevalence and parental perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine use by children with cancer in a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(1):70–74. doi:10.1002/pbc.2179818937312

- Suparmi S, Widiastuti D, Wesseling S, Rietjens IMCM. Natural occurrence of genotoxic and carcinogenicalkenylbenzenes in Indonesian jamu and evaluation of consumerrisks. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;118:53–67. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.05929727721

- Suparmi S, Ginting AJ, Mariyam S, Wesseling S, Rietjens IMCM. Levels of methyleugenol and eugenol in instant herbal beveragesavailable on the Indonesian market and related risk assessment. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;125:467–478. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.00130721739

- Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. Medication use among children <12 years of age in the United States: results from the Slone Survey. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):446–454. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-286919651573

- Menniti-Ippolito F, Forcella E, Bologna E, Gargiulo L, Traversa G, Raschetti R. Use of unconventional medicine in children in Italy. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(12):690. doi:10.1007/s00431-002-1085-712536996

- Shih C-C, Liao C-C, Su Y-C, Yeh TF, Lin J-G. The association between socioeconomic status and traditional Chinese medicine use among children in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:27. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-2722293135

- Melesse TG, Ayalew Y, Getie GA, Mitiku HZ, Tsegaye G. Prevalence and factors associated with parental traditional medicine use for children in Motta Town, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia, 2014. Altern Integr Med. 2015;4:179. doi:10.4172/2327-5162.1000179

- Strauss J, Witoelar F, Sikoki B The fifth wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS5): overview and field report. 3 2016 WR-1143/1-NIA/NICHD, 2016.

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. The prevalence of edentulism and their related factors in Indonesia, 2014/15. BMC Oral Health. 2018;118. doi10.1186/s12903-018-0582-7

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. High prevalence of depressive symptoms in a national sample of adults in Indonesia: childhood adversity, sociodemographic factors and health risk behaviour. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;33:52–59. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2018.03.01729529418

- Xe: The World’s Trusted Currency Authority; 2019. Available from: https://www.xe.com/. Accessed 218, 2019.

- Du Y, Knopf H. Self-medication among children and adolescents in Germany: results of the National Health Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):599–608. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03477.x19843063

- Handayani L, Suparto H, Suprapto A. Traditional system of medicine in Indonesia In: Chaudhury RR, Rafei UM, editors. Traditional Medicine in Asia. New Dehli: World Health Organization; 2001:47–68.

- Italia S, Brand H, Heinrich J, Berdel D, von Berg A, Wolfenstetter SB. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among children from a German birth cohort (GINIplus): patterns, costs, and trends of use. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:49. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0569-825885673

- Seo H-J, Baek S-M, Kim SG, Kim T-H, Choi SM. Prevalence of complementary prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in a community-based population in South Korea: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:260–271. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2013.03.00123642959