Abstract

Thyroid nodules are a common clinical problem for surgeons. The clinical importance of nodules is the need to exclude thyroid cancer, which occurs in 5%–15% of patients. If fine needle aspiration cytology is positive, or suspicious for malignancy, surgery is recommended. During the past decade, with the tendency to develop smaller incisions, an endoscopic approach has been applied to thyroid surgery, called minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy. This approach was immediately followed by other minimally invasive or scarless neck techniques, such as the breast approach, axillary-breast approach, and robot-assisted method. All these techniques follow the same principles of surgery and oncology. This review presents the current surgical management of the thyroid gland, including the surgical techniques and compares them by describing benefits and drawbacks of each one.

Introduction

The thyroid gland, or simply, the thyroid, is one of the largest endocrine glands, which is found in the neck, inferior to the thyroid cartilage. The thyroid produces the hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). These hormones regulate the body’s metabolism and affect the growth and many other functions of various systems of the human body. The thyroid also produces calcitonin, which plays a role in calcium metabolism. Thyroid disorders include hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and thyroid nodules. Nodules are commonly benign neoplasms, but may be cancerous. All these disorders can lead to goiter, a swelling of the thyroid gland that can lead to a swelling of the neck. Some thyroid disorders need surgical treatment. These disorders are thyroid nodule with diameter more than 1 cm and fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy for suspected neoplasm (Grade A),Citation1,Citation2 thyroid nodule with diameter less than 1 cm and FNA indeterminate more than once (Grade A),Citation1,Citation2 thyroid nodule and FNA positive for malignancy (Grade A),Citation2–Citation4 multiple thyroid nodules because of the same malignant possibility as one positive nodule,Citation5,Citation6 differentiated thyroid cancer (Grade A),Citation7 medullary thyroid cancer (Grade A),Citation8,Citation9 prophylactic in cases with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 2A syndrome,Citation10 anaplastic carcinoma,Citation11 and thyrotoxic diseases.Citation12,Citation13 We review the current surgical management of those thyroid disorders, including surgical techniques, and compare them by describing their benefits and drawbacks.

Thyroid surgical history

Between 1873 and 1893, Billroth and Kocher standardized the dissection and excision of the thyroid gland during surgery.Citation14 With the tendency to develop smaller incisions during the past decade, an endoscopic approach has been applied to surgery of both thyroid and parathyroid glands. Other minimally invasive techniques were also developed by other surgeons.Citation15 Until 2000, those techniques have been either abandoned or further developed. The most common minimally invasive technique is minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy (MIVAT), which has been set up and described for the first time by Miccoli and colleagues in Pisa.Citation16 Other minimally invasive approaches for the thyroid gland are the cervical, the axillary, and the breast approaches, all of them famous in Asian countries, with endoscopic thyroidectomy via the breast approach (BAET) the most popular procedure in China.Citation17 Robotic thyroidectomy is a new approach that offers many benefits, mostly the elimination of the incision in the neck, but no Level I evidence exists to support the surgeon’s preference for this technique.Citation18

Surgical techniques

Traditional thyroidectomy

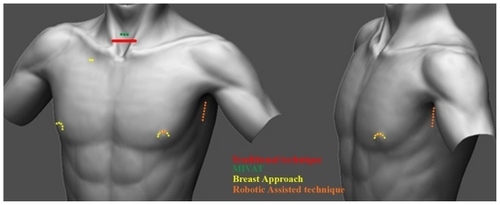

Most departments of surgery follow the standard technique. Citation19,Citation20 With the neck extended, the skin is marked, a 5–6 cm Kocher incision is made (about 1 cm above the sternal notch), flaps are raised, and the strap muscles are divided transversely (). Attention is first turned to one lobe where the upper pole is mobilized through the avascular space with individual ligation of the vessels to protect the external laryngeal nerve. The lower pole is then mobilized by ligating vessels on the thyroid capsule, while carefully protecting the blood supply of the parathyroid glands. Parathyroid glands that cannot be preserved because of their anatomic location are resected and transplanted in the array surface of the sternomastoid muscle. In the past, recurrent laryngeal nerve was routinely identified during dissection,Citation19,Citation20 but since then, the nerve has been protected by the development of surgical techniques over recent years, which led to capsular dissection and ligation near the thyroid gland. The remaining lobe is removed by the same technique. Hemostasis was secured, the strap muscles approximated, the platysma layer sutured, and the skin was closed with subcuticular sutures.

Minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy

The MIVAT technique was described for the first time by Miccoli and colleagues.Citation16 MIVAT is now considered as a safe procedure for thyroidectomy. Miccoli and colleaguesCitation16 characterized MIVAT by a single access of 1.5 cm in the middle area of the neck, approximately 2 cm above the sternal notch (). The midline is incised, and a blunt dissection is carried out with tiny spatulas to separate the strap muscles from the underlying thyroid lobe. From this point on, the procedure is performed endoscopically on a gasless basis with an external retraction. An endoscope of 5 mm, 30° is used. The optical magnification allows an excellent vision of both the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent nerve, which are prepared together with the upper parathyroid gland. The vessels are ligated between clips or with the UltraCision® harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc, Cincinnati, OH) until the completely freed lobe can be extracted by gently pulling it out through the skin incision. After checking the recurrent laryngeal nerve once again, the lobe is finally removed completely. The other lobe is removed by the same method. The incision is closed by means of two subcuticular stitches and a skin sealant. No drainage is necessary.

Endoscopic thyroidectomy by the breast approach

The first cases of this procedure, which is famous in China,Citation21 were reported in 1998 by Ishii and colleagues.Citation22 The aim of this technique was to avoid the presence of any scars in the neck. The two working ports were inserted through circumareolar incisions on both breasts. The camera port (1.5–2.0 cm) was placed over the right parasternal region (), which is the longest incision. A subcutaneous tunnel is created using blunt dissection and a subplatysmal space is created. Insufflation with CO2 is started to ready the subplatysmal working space. Once the operative camera is ready, working instruments are introduced until the thyroid bed is reached. From that point, the steps of the procedure are the same as the standard classical technique, but all are performed endoscopically by first working in one pole and then the other.

Robotic thyroidectomy

The introduction of robot technology has revolutionized the surgical management of prostate cancer. The da Vinci robotic surgical system uses magnified stereoscopic visualization and flexible instrumentation that provide a freedom of movement similar to that of the human wrist. These features suggest it may be well suited for head and neck surgery, including selective neck dissection ().Citation23–Citation26 Using this method, the patient is positioned in a supine position on a small shoulder roll. The ipsilateral arm is placed on an arm board and extended cephalad to expose the axilla. A 5- to 6-cm skin incision is made along the line marked in the axilla at the posterior aspect of the pectoralis. The arm is placed in its natural position to confirm that the marked incision will be hidden in the axilla postoperatively. A small incision (0.8 cm in length) is made on the medial side of the anterior chest wall to insert the fourth robot arm, 2 cm superiorly, and 6–8 cm medially from the nipple (). Dissection is performed using electrocautery above the pectoralis major muscle to create a space using serially longer retractors to elevate the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and platysma. The space is opened superiorly, the omohyoid is retracted superficially and posterolaterally or divided, and the sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles are elevated from the thyroid gland. To maintain a working space, a spatula-shaped external retractor (Chung’s thyroid retractor) with table mount lift is placed under the strap muscles and secured to the table mount lift. The operation proceeded in the same manner as open thyroidectomy.

Discussion

Thyroid nodules are a common clinical problem and differentiated thyroid cancer is becoming increasingly prevalent. The clinical importance of thyroid nodules rests with the need to exclude thyroid cancer which occurs in 5%–15% of patients depending on age, sex, radiation exposure history, family history, and other factors.Citation27 Differentiated thyroid cancer, which includes papillary and follicular cancer, comprises the vast majority (90%) of all thyroid cancers.Citation28 If the FNA cytology is positive, or suspicious for malignancy, surgery is recommended. Thyroid surgery has undergone vast changes in the last 120 years. The principles of safe and efficient thyroid surgery have been established since the early 19th century and the “10 commandments” of thyroid surgeryCitation29 are universally accepted as the standard for traditional open thyroidectomy.

The goals of initial therapy of thyroid cancer, with thyroidectomy are as follows: to remove the primary tumor that has extended beyond the thyroid capsule and involved cervical lymph nodes;Citation30–Citation32 to minimize treatment-related morbidity; to permit accurate staging of thyroid diseases;Citation33,Citation34 to facilitate postoperative multidisciplinary treatment; to permit accurate long-term surveillance and follow-up; and to minimize the risk of recurrence or metastatic spread of the cancer. Surgery is the most important treatment to influence the prognosis, while radioactive iodine treatment, thyroid-stimulating hormone suppression, and external beam irradiation each play adjunctive roles in many patients.Citation34–Citation36

Regional lymph node metastases are present at the time of diagnosis in 20%–90% of patients with papillary carcinoma (PTC) and a lesser proportion of patients with other histotypes.Citation31,Citation32 Although PTC lymph node metastases are reported by some to have no clinically important effect on outcome in low-risk patients, a study of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database found, among 9904 patients with PTC, that lymph node metastases, age greater than 45 years, distant metastasis, and large tumor size significantly predicted poor outcome on multivariate analysis.Citation37 All-cause survival at 14 years was 82% for PTC without lymph node and 79% with lymph node metastases (P < 0.05). In many patients, lymph node metastases in the central compartment (Level VI: contains the adjacent nodes bordered superiorly by the hyoid bone, inferiorly by the innominate artery, and laterally on each side by the carotid sheaths) do not appear abnormal preoperatively with imaging or by inspection at the time of surgery.Citation38 Central compartment dissection (therapeutic or prophylactic) can be achieved with low morbidity in experienced hands.Citation39–Citation42 Therapeutic lateral neck compartmental lymph node dissection should be performed in patients with biopsy-proven metastatic lateral cervical lymphadenopathy (with a recommendation rating B).Citation7

There is a constant drive to produce better cosmesis, shorten hospital stay, and reduce postoperative discomfort and complications. Numerous other techniques have been described that are classified as minimally invasive, and have been developed in the late 1990s to address these issues. These techniques concentrate on how the thyroid gland is approached. They are categorized in cervical approaches, where the incision is in the neck, and extracervical, where the incisions are not in the neck. Only the operations that have a cervical incision < 3 cm, that permit direct access to the thyroid gland and all adjacent structures resulting in a safe dissection, should be classed as minimally invasive.Citation43 Endoscopic procedures are those that are carried out entirely via the endoscopic ports,Citation44 and those video-assisted procedures where some steps are performed via a small incision without the endoscope. The MIVAT technique seems to be the most widely adopted minimally invasive technique.

Total open thyroidectomy is such a procedure, where considerable controversy still exists with respect to its use for all surgical conditions of the thyroid gland, which was reported in the first part of this article (). The incidence of permanent complications after total thyroidectomy varies considerably from center to center. In experienced hands, however, the incidence is acceptably low with 1% nerve injury and 3% hypoparathyroidism when total thyroidectomyCitation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation45,Citation46 was performed for thyroid cancer. These latter complications were attributable to the more extensive surgery performed because of the degree of spread of the malignancy rather than to operative techniques. The incidence of complications increases as the complexity of the procedure increases.Citation8,Citation10–Citation13,Citation19,Citation20 Reoperation for recurrent disease carries a very significant risk of damage to both the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the parathyroid glands.

Table 2 Indications, advantages, and disadvantages of surgical techniques for thyroid surgery

The video-assisted technique follows the same principles as standard thyroidectomy,Citation47 and the main difference is that the incision is much smaller (1.5–2 cm) while the view of the operating field is maintained by two assistants: one at the head end of the patient holding retractors, and another manipulating a 5 mm, 30° endoscope from the left of the patient. Extension of the neck is not required. Drains are not routinely placed when the skin is closed. The operating time is longer than traditional techniques, but decreases with surgeon experience.Citation48,Citation49

Careful patient selection for minimally invasive thyroidectomy influences the outcome whether treating benign or malignant thyroid conditions. When contemplating a minimally invasive approach, indications are based on overall thyroid size, size and histology of thyroid nodules, and thyroid volume. Most authors consider size limits of 30 mL in volume, thyroid nodule size of <30 mm in diameter, and actual cancer size of <20 mm to be considered eligible for minimally invasive surgical techniques ().Citation50 If patients have large goiters, the goiter size can definitely dictate the extent of the incision and also contribute to technical limitations when operating in the tight confines of the central neck compartment. When discussing the indications of MIVAT for differentiated thyroid cancer – papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell cancers – it is important to keep in mind the biology of disease as well as the oncologic principles of surgery. MIVAT for thyroid cancers warrants a more strict set of indications. For large or aggressive thyroid cancers, a standard Kocher incision is indicated, especially if there is a high index of suspicion of local–regional invasion. Standard thyroidectomy techniques should also be considered in patients with a history of thyroiditis where dissection may be compromised by tissue adherence and bleeding that precludes adequate visualization of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands. Other contraindications to minimally invasive techniques include a history of previous neck surgery, head/neck irradiation, and the presence of palpable lymphadenopathy. Medullary thyroid cancer patients should undergo traditional thyroidectomy with appropriate ipsilateral or bilateral functional neck dissection as these tumors are not radioiodine sensitive and complete surgical resection is the centerpiece of management.Citation7 In poorly differentiated papillary thyroid cancer or anaplastic thyroid cancer, patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging, large neck mass with evidence of locoregional invasion. This type of cancer is a contraindication to employing minimally invasive or endoscopic techniques. All these techniques have been thoroughly researched since the first description of the technique by Ganger and colleagues,Citation51 and later by Miccoli and colleagues.Citation15,Citation16,Citation47–Citation56

The efficacy and safety of video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) have been verified in quite large multi-institutional series.Citation57 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that VAT has some advantages over traditional thyroidectomy in terms of cosmetic results and postoperative pain ().Citation58,Citation59 Lombardi and colleaguesCitation55 proved the safety of VAT versus the traditional procedure (). This study strongly confirmed the safety of VAT because it demonstrated that thyroid gland manipulation is not substantially different between VAT and traditional thyroidectomy and that there is no additional risk of thyroid capsule rupture and thyroid cells seeding in patients who undergo VAT, if the procedure is correctly conducted by an expert endocrine surgeon. Significant advantages of VAT over open thyroidectomy in terms of less painful postoperative course and better cosmetic result have been also confirmed.Citation16,Citation43,Citation44,Citation47–Citation50,Citation52–Citation59

Table 1 Published data from large studies comparing operation outcomes between surgical techniques

The need for an esthetically pleasing scar after thyroid surgery has led surgeons to develop endoscopic surgery in the neck. Endoscopic surgery by the cervical approach seems to be mostly used in China.Citation60 BAET has the following advantages: concealing scars easily by wearing undergarments; providing a view of the surgical field equivalent to that obtained during open surgery; and enabling manipulation of bilateral lesions without the necessity of adding extra incisions ().Citation61 Therefore, BAET became the most popular procedure in Asian countries (more than 95% of all endoscopic thyroidectomies in China).Citation21,Citation61

The indication for endoscopic thyroidectomy is commonly the management of benign thyroid nodules. The accepted indications for BAETCitation21,Citation62–Citation64 are unilateral or bilateral benign lesions, including follicular adenoma, cystic lesions, multinodular goiter, with a diameter of <6 cm and thyrotoxicosis with less than second-degree enlargement of the thyroid gland. For experienced surgeons, the inclusion criteria for thyroid carcinoma should be papillary microcarcinoma (<1 cm) without signs of capsule invasion and involvement of central or lateral compartment lymph nodes ().Citation62–Citation64

A randomized, controlled trial (RCT) was conducted by Jiang and colleaguesCitation65 to evaluate the technical feasibility of BAET. Jiang and colleagues found BAET was as safe as open surgery with the same levels of complication rate. The advantage of BAET was the satisfaction of the patient for the cosmetic results. Disadvantages included longer operation time and higher cost. Although the cosmetic result is much better in BAET, there are widespread concerns about greater postoperative pain (probably due to larger plane of tissue dissection). Although the RCT indicated that the operation time was longer in the endoscopic group, the same research team showed that it could be reduced with the accumulation of surgical experience.Citation66

Endoscopic thyroidectomy is a very difficult technique because different visualization and precise manipulation of the surgical field by a specialist is necessary. Therefore, the endoscopic approach of the thyroid remains limited in application in a small number of specialist centers worldwide.

Robotic assistance during thyroid surgery has been used in Korea since late 2007.Citation23–Citation25 Compared with endoscopic thyroidectomy, the use of a robot in an endoscopic approach via the axilla provides a better view of the thyroid bed. The wrist action of the robot also provides a greater degree of movement than afforded by the use of simple endoscopic instruments. Tremor is also eliminated ().Citation23–Citation25 The indications of this procedure are minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma 4 cm or less in diameter or a papillary thyroid carcinoma 2 cm or less in diameter,Citation23–Citation25 but in future, the application of robotic technology in endoscopic thyroid surgeries could overcome the limitations of conventional endoscopic surgeries in the surgical management of selected patients with thyroid cancer (). Strict criteria exclude patients from robotic thyroidectomy: previous neck operations; prior vocal fold paralysis or a history of voice or laryngeal disease requiring therapy; malignancy with extrathyroid invasion; multiple neck node metastases; perinodal infiltration at a metastatic lymph node; distant metastasis; and a lesion located in the thyroid dorsal area that can lead to a possible injury of the trachea, esophagus, or recurrent laryngeal nerve during the procedure. Previous studies complied the indications and limitations of the technique and show that robot-assisted thyroidectomy is as effective and safe as traditional thyroidectomy ().Citation23,Citation24 They also show several advantages over conventional endoscopic thyroid surgery such as a three-dimensional working field, a magnified view, and a tremor-filtering system, all of which enable a surgeon to preserve the parathyroid gland and recurrent laryngeal nerve more easily and safely (). As with any new procedure, it requires a special set of skills, the operative time presented is increased, and the operating theater costs are higher. Robotic thyroidectomy using a transaxillary approach leaves the patient with an incision scar in the axilla that is completely covered by the patient’s arm when in a natural position, which makes the small central incision almost invisible. Previous studies have reported that patients who underwent thyroidectomy by the transaxillary approach reported mild pain or discomfort in the neck and the anterior chest wall.Citation67–Citation70 This may be caused by the extended dissection from the axilla to the neck required to achieve an adequate surgical field.

The thyroidectomy technique demands careful surgical dissection, absolute hemostasis, en bloc tumor resection, and adequate visualization of the operative field. All of the above can be accomplished with many surgical techniques that follow the same principles. Factors such as tumor size, histology, the presence or absence of enlarged lymph nodes, evidence of locoregional invasion, the learning curve of each procedure, and total cost increase demand for surgical procedures that avoid visible scars while maintaining optimal functional and ideal cosmetic results. These factors play a role in selecting an operative approach when treating thyroid malignancy. Although several reports on operative outcomes of the robotic technique have appeared, no prospective trials comparing the clinical results of robotic and conventional open thyroidectomy have been described. If further prospective randomized trials confirm the advantages of robotic thyroidectomy compared with conventional open surgery, this technique may become the preferred option for most patients undergoing surgery for thyroid cancer.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. All authors contributed equally to the preparation of this paper.

References

- KelmanASRathanALeibowitzJBursteinDEHaberRSThyroid cytology and the risk of malignancy in thyroid nodules: importance of nuclear atypia in indeterminate specimensThyroid20011127127711327619

- TuttleRMLemarHBurchHBClinical features associated with an increased risk of thyroid malignancy in patients with follicular neoplasia by fine-needle aspirationThyroid199883773839623727

- GoldsteinRENettervilleJLBurkeyBJohnsonJEImplications of follicular neoplasms, atypia, and lesions suspicious for malignancy diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodulesAnn Surg200223565666211981211

- SchlinkertRTvan HeerdenJAGoellnerJRFactors that predict malignant thyroid lesions when fine-needle aspiration is “suspicious for follicular neoplasm”Mayo Clin Proc1997729139169379692

- MarquseeEBensonCBFratesMCUsefulness of ultrasonography in the management of nodular thyroid diseaseAnn Intern Med2000133969670011074902

- SegevDLClarkDPZeigerMAUmbrichtCBeyond the suspicious thyroid fine needle aspirate. A reviewActa Cytol20034770972214526667

- CooperDSDohertyGMHaugenBRAmerican Thyroid Association Guidelines TaskforceManagement guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancerThyroid20061610914116420177

- ShermanSIThyroid carcinomaLancet200336150151112583960

- GharibHGoellnerJRJohnsonDAFine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid. A 12-year experience with 11,000 biopsiesClin Lab Med1993136997098222583

- SkinnerMAMoleyJADilleyWGOwzarKDebenedettiMKWellsSAJrProphylactic thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2AN Engl J Med20053531105111316162881

- NelCJvan HeerdenJAGoellnerJRAnaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: A clinopathologic study of 82 casesMayo Clin Proc19856051583965822

- ReeveTThyroid disease – Role of the surgeon at the turn of the centuryWorld J Surg200024885

- GoughIRWilkinsonDTotal thyroidectomy for management of thyroid diseaseWorld J Surg20002496296510865041

- EllisHThyroid and parathyroidThe Cambridge Illustrated History of SurgeryCambridge, MACambridge University Press2009195209

- MiccoliPMinutoMNBertiPMaterazziGUpdate on the diagnosis and treatment of differentiated thyroid cancerQ J Nucl Med Mol Imaging20095346547219910899

- MiccoliPBertiPConteMBendinelliCMarcocciCMinimally invasive surgery for thyroid small nodules: preliminary reportJ Endocrinol Invest1999228495110710272

- NgWTEndoscopic thyroidectomy in ChinaSurg Endosc2009231675167719343423

- PerrierNDRandolphGWInabnetWBMarpleBFVanHeerdenJKuppersmithRBRobotic thyroidectomy: a framework for new technology assessment and safe implementationThyroid201020121327133221114381

- ReeveTSRight subtotal thyroid lobectomyMaltRASurgical Techniques IllustratedBoston, MALittle Brown and Co19776170

- ReeveTSThyroidectomy: subtotal lobectomy and lobectomyDudleyHPoriesWRob and Smiths Operative Surgery: General Principles, Breast and Extracranial Endocrines4th edLondon, UKButterworths1982341352

- ZhangWJiangDZLiuSCurrent status of endoscopic thyroid surgery in ChinaSurg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech201121677121471794

- IshiiSOghamiMArisawaYOhmoriTNogaKKitajimaMEndoscopic thyroidectomy with anterior chest wall approachSurg Endosc199812611

- KangSWLeeSCLeeSHRobotic thyroid surgery using a gasless, transaxillary approach and the da Vinci S system: the operative outcomes of 338 consecutive patientsSurgery20091461048105519879615

- KangSWJeongJJYunJSRobot-assisted endoscopic surgery for thyroid cancer: experience with the first 100 patientsSurg Endosc2009232399240619263137

- KangSWJeongJJNamKHChangHSChungWYParkCSRobot-assisted endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid malignancies using a gasless transaxillary approachJ Am Coll Surg2009209e1e719632588

- LewisCMChungWYHolsingerFCFeasibility and surgical approach of transaxillary approach robotic thyroidectomy without CO(2) insufflationHead Neck20103212112619998442

- HegedusLClinical practice. The thyroid noduleN Engl J Med20043511764177115496625

- HayIDBergstralhEJGoellnerJREbersoldJRGrantCSPredicting outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma: development of a reliable prognostic scoring system in a cohort of 1779 patients surgically treated at one institution during 1940 through 1989Surgery199311410501057 discussion 1057–10588256208

- HobbsCGLWatkinsonJCThyroidectomySurgery200725474478

- ShahMDHallFTEskiSJWitterickIJWalfishPGFreemanJLClinical course of thyroid carcinoma after neck dissectionLaryngoscope20031132102210714660910

- WangTSDubnerSSznyterLAHellerKSIncidence of metastatic well-differentiated thyroid cancer in cervical lymph nodesArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg200413011011314732779

- BrierleyJDPanzarellaTTsangRWGospodarowiczMKO’SullivanBA comparison of different staging systems predictability of patient outcome. Thyroid carcinoma as an exampleCancer199779241424239191532

- HayIDThompsonGBGrantCSPapillary thyroid carcinoma managed at the Mayo Clinic during six decades (1940–1999): temporal trends in initial therapy and long-term outcome in 2444 consecutively treated patientsWorld J Surg20022687988512016468

- MazzaferriELAn overview of the management of papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomaThyroid1999942142710365671

- MazzaferriELLong-term outcome of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma: effect of therapyEndocr Pract2000646947611155222

- KimTHYangDSJungKYKimCYChoiMSValue of external irradiation for locally advanced papillary thyroid cancerInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys2003551006101212605980

- PodnosYDSmithDWagmanLDEllenhornJDThe implication of lymph node metastasis on survival in patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancerAm Surg20057173173416468507

- RobbinsKTShahaARMedinaJECommittee for Neck Dissection Classification, American Head and Neck SocietyConsensus statement on the classification and terminology of neck dissectionArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg200813453653818490577

- GimmORathFWDralleHPattern of lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid carcinomaBr J Surg1998852522549501829

- HenryJFGramaticaLDenizotAKvachenyukAPucciniMDefechereuxTMorbidity of prophylactic lymph node dissection in the central neck area in patients with papillary thyroid carcinomaLangenbecks Arch Surg19983831671699641892

- CheahWKAriciCItuartePHSipersteinAEDuhQYClarkOHComplications of neck dissection for thyroid cancerWorld J Surg2002261013101612045861

- WhiteMLGaugerPGDohertyGMCentral lymph node dissection in differentiated thyroid cancerWorld J Surg20073189590417347896

- HenryJFMinimally invasive thyroid and parathyroid surgery is not a question of length of the incisionLangenbecks Arch Surg200839362162618716792

- SlotemaETSebagFHenryJFWhat is the evidence for endoscopic thyroidectomy in the management of benign thyroid disease?World J Surg2008321325133218327525

- ClarkOHTotal thyroidectomy: the treatment of choice for patients with differentiated thyroid cancerAnn Surg19821963613707114941

- PeizikSLThe place of total thyroidectomy in the management of 909 patients with thyroid diseaseAm J Surg19761324804831037071

- TimonCRaffertyMMinimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy (MIVAT): technique, advantages, and disadvantagesOperative Techniques in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery200819814

- Del RioPSommarugaLCataldoSRobuschiGArcuriMFSianesiMMinimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy: the learning curveEur Surg Res200841333618434737

- LombardiCPRaffaelliMDe CreaCD’AmoreABellantoneRVideoassisted thyroidectomy: lessons learned after more than one decadeActa Otorhinolaryngol Ital20092931732020463836

- RuggieriMStranieroAMaiuoloAThe minimally invasive surgical approach in thyroid diseasesMinerva Chir20076230931417947942

- GagnerMEndoscopic subtotal parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidismBr J Surg1996838758696772

- MiccoliPMaterazziGBertiPMinimally invasive thyroidectomy in the treatment of well differentiated thyroid cancers: indications and limitsCurr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg20101811411820182356

- ChaoTCLinJDChenMFVideo-assisted open thyroid lobectomy through a small incisionSurg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech200414151915259579

- El-LabbanGMMinimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy versus conventional thyroidectomy: a single-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trialJ Minim Access Surg200959710220407568

- LombardiCPRaffaelliMPrinciPSafety of video-assisted thyroidectomy versus conventional surgeryHead Neck200527586415459914

- MamaisCCharakliasNPothulaVBDiasAHawthorneMNirmal KumarBIntroduction of a new surgical technique: minimally invasive video-assisted thyroid surgeryClin Otolaryngol201136515621414153

- MiccoliPBellantoneRMouradMWalzMRaffaelliMBertiPMinimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy: multiinstitutional experienceWorld J Surg20022697297512016476

- BellantoneRLombardiCPBossolaMVideo-assisted vs conventional thyroid lobectomy – a randomized trialArch Surg200213730130411888453

- MiccoliPBertiPRaffaelliMMaterazziGBaldacciSRossiGComparison between minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy and conventional thyroidectomy: a prospective randomized studySurgery20011301039104311742335

- Li-TsangCWLauJCChanCCPrevalence of hypertrophic scar formation and its characteristics among Chinese populationBurns20053161061615993306

- NgWTEndoscopic thyroidectomy in ChinaSurg Endosc2009231675167719343423

- WangPLiZYXuSMEndoscopic thyroidectomy through anterior chest and breast approach for papillary thyroid microcarcinomaChin J Surg2008461480148219094626

- QiuMKey techniques in endoscopic thyroid and parathyroid surgeryJ Surg Concepts Pract200914377378

- SunYMBaiJFLuWXEfficacy of endoscopic thyroidectomy for treating thyroid diseasesChin J Surg20074516471648

- ZhangWJiangZGJiangDZThe minimally invasive effect of breast approach endoscopic thyroidectomy: an expert’s experienceClin Dev Immunol2010201045914320827304

- LiuSQiuMJiangDZThe learning curve for endoscopic thyroidectomy: a single surgeon’s experienceSurg Endosc2009231802180619247710

- IkedaYTakamiHSasakiYTakayamaJNiimiMKanSClinical benefits in endoscopic thyroidectomy by the axillary approachJ Am Coll Surg200319618919512595044

- IkedaYTakamiHSasakiYTakayamaJKuriharaHAre there significant benefits of minimally invasive endoscopic thyroidectomy?World J Surg2004281075107815490052

- KohYWParkJHKimJWLeeSWChoiECEndoscopic hemithyroidectomy with prophylactic ipsilateral central neck dissection via an unilateral axillo-breast approach without gas insufflation for unilateral micropapillary thyroid carcinoma: preliminary reportSurg Endosc20102418819719688395

- IkedaYTakamiHSasakiYTakayamaJNiimiMKanSComparative study of thyroidectomies: endoscopic surgery versus conventional open surgerySurg Endosc2002161741174512140635

- LangHChowMPA comparison of surgical outcomes between endoscopic and robotically assisted thyroidectomy: the authors’ initial experienceSurg Endosc2011251617162321088857

- TaeKJiYBShoSHKimKRKimDWKimDSInitial experience with a gasless unilateral axillo-breast or axillary approach endoscopic thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: comparison with conventional open thyroidectomySurg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech201121316216921654299

- LeeJNahKYKimRMAhnYHSohEYChungWYDifferences in postoperative outcomes, function, and cosmesis: open versus robotic thyroidectomySurg Endosc2010243186319420490558