Abstract

Background

The purpose of this systematic review was to determine the effectiveness and implementation of advanced allied health assistant roles.

Methods

A systematic search of seven databases and Google Scholar was conducted to identify studies published in English peer-reviewed journals from 2003 to 2013 and reporting on the effectiveness and implementation of advanced allied health assistant (A/AHA) roles. Reference lists were also screened to identify additional studies, and the authors’ personal collections of studies were searched. Studies were allocated to the National Health and Medical Research Council hierarchy of evidence, and appraisal of higher-level studies (III-1 and above) conducted using the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet for included systematic reviews or the PEDro scale for level II and III-1 studies. Data regarding country, A/AHA title, disciplines, competencies, tasks, level of autonomy, clients, training, and issues regarding the implementation of these roles were extracted, as were outcomes used and key findings for studies investigating their effectiveness.

Results

Fifty-three studies were included, and most because they reported background information rather than investigating A/AHA roles, this representing low-level information. A/AHAs work in a range of disciplines, with a variety of client groups, and in a number of different settings. Little was reported regarding the training available for A/AHAs. Four studies investigated the effectiveness of these roles, finding that they were generally well accepted by clients, and provided more therapy time. Issues in integrating these new roles into existing health systems were also reported.

Conclusion

A/AHA roles are being implemented in a range of settings, and appear to be effective in terms of process measures and stakeholder perceptions. Few studies have investigated these roles, indicating a need for research to be conducted in this area to enable policy-makers to consider the value of these positions and how they can best be utilized.

Introduction

The shortage of health professionals in Australia has led governments to consider workforce redesign to utilize better their human resources to meet the health needs of the population. One aspect of redesign in the health workforce is advanced practice or extended scope roles. Advanced scope of practice refers to “a role that is within the currently recognized scope of practice for that profession, but that through custom and practice has been performed by other professions. The advanced role would require additional training, competency development, as well as significant clinical experience and formal peer recognition. This role describes the depth or practice”,Citation1 whilst extended scope of practice is defined as “a role that is outside the currently recognized scope of practice and requires legislative change. Extended scope of practice requires some method of credentialing following additional training, competency development, and significant clinical experience… This role describes the breadth of practice”.Citation1

Although advanced/extended practice is most commonly associated with nurse practitioner roles, and extended scope physiotherapists, there is also a shift towards expanding the roles of allied health assistants (AHA). The current scope of practice of AHAs was reported in a recent systematic review,Citation2 with duties including assisting allied health professionals, providing physical and social support to patients, administering clinical services and modalities, transferring patients, communicating patient progress, communicating with other staff, assisting with mobility and gait, providing equipment, patient education, provision of health care to patients, supervising/conducting exercise classes, preparing patients for treatment, conducting individual or group therapy, coordinating and assisting in the operation of services, assisting and coordinating health service, administration, stock ordering/requisition, preparing/maintaining the environment, maintaining equipment, health promotion, monitoring and updating health care databases, recording/statistics/database, housekeeping, and cleaning. This systematic review did not report the role of advanced allied health assistants (A/AHA), although there are examples of advanced roles being implemented in Australia, highlighting the need for a more specific review in this area. In better understanding these roles, and how they have been implemented elsewhere, policy-makers will be better able to determine whether such roles are worthwhile, how they can best be utilized, and potential issues in the implementation of A/AHA roles.

The working definition of A/AHA used for the purpose of this review is any assistant role supporting allied health professionals, working beyond the skill base or level of responsibility normally expected for an AHA. It is acknowledged that there is likely to be a range of terms used to describe these roles, eg, advanced, senior, or extended scope, as well as terms reflecting the allied health disciplines they support (eg, physiotherapy, occupational therapy), or more generic health care terms (eg, health care assistant, support worker).

This systematic review sought to answer the following questions:

What is the scope of practice of A/AHAs?

What client groups do A/AHAs work with?

What settings do A/AHAs work in?

What training is available for A/AHAs?

How effective are A/AHA roles in terms of health, cost, and process outcomes?

What are the workforce issues for A/AHAs?

Materials and methods

Systematic search

A systematic search of key library databases (Embase [OvidSP], Medline [OvidSP], Scopus, Web of Science, Nursing and Allied Health Source [ProQuest], Health and Medical Complete [ProQuest], and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], EbscoHost) was conducted in February 2013, using a comprehensive list of search terms (see http://www.unisa.edu.au/PageFiles/68220/AAHA%20paper%20appendix%20pdf%20(2).pdf). These terms were developed through iterative discussion and by consulting systematic reviews of AHA roles.Citation2,Citation3 These terms were searched in all fields, and limited to peer-reviewed studies published in English from 2003 to 2013 where permitted by the databases. Additionally, a similar search was conducted in Google Scholar using the same terms (see http://www.unisa.edu.au/PageFiles/68220/AAHA%20paper%20appendix%20pdf%20(2).pdf). This search was also limited to 2003–2013.

To widen the search, the reference lists of all included peer-reviewed studies, and the reference lists of any systematic reviews identified through the search were manually screened to identify any study titles which made reference to A/AHA, or which referenced A/AHA in the text. Additionally, the authors screened their personal collections of studies for any relevant information. If further studies were included, this process was repeated until saturation was reached.

Study identification

All studies obtained were exported into EndNote X6 where duplicate studies were excluded. The titles and abstracts of all remaining studies was screened, before the full texts were obtained and screened. Studies were excluded if they:

did not involve A/AHA (eg, the assistant was not identified as advanced, senior, or extended scope, or did not perform tasks identified as extended scope or advanced practice, or they clearly stated that their role was to support non-AHA staff, eg, nurses)

only reported potential A/AHA roles, rather than those which had been implemented

were not published between 2003 and 2013 (or where no date could be determined)

were not published in English

were not available in full text (eg, conference abstracts)

were not published in peer-reviewed journals

did not include any information pertaining to the six review questions.

Due to the broad nature of questions for this review, studies of any design were included. Furthermore, any paper reporting relevant data was included, even if this was not investigated in the study (eg, relevant information for this review was reported in the background). Where this relevant information was citing another reference, the original study was identified to ensure it (the original study) met the inclusion criteria. Where all relevant information was cited from other references, the study was excluded.

Assigning levels of evidence

Where the findings of a study informed the review questions (ie, not solely background information) the study design was identified, and assigned to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) hierarchy of evidence.Citation4

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal was only conducted for studies identified as level III-1 or higher. Systematic reviews were appraised using the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet,Citation5 and the PEDro scaleCitation6 was used for level II and III-1 studies. Lower-level studies were not appraised due to the biases inherent in their designs.

Data extraction

Relevant data were extracted from all included studies, according to the headings reported in . Where relevant information was reported with a reference, the data were not extracted, but the reference was obtained and included in the review if it met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1 Data extraction

Analysis

Due to the nature of the questions posed, all data are reported descriptively.

Results

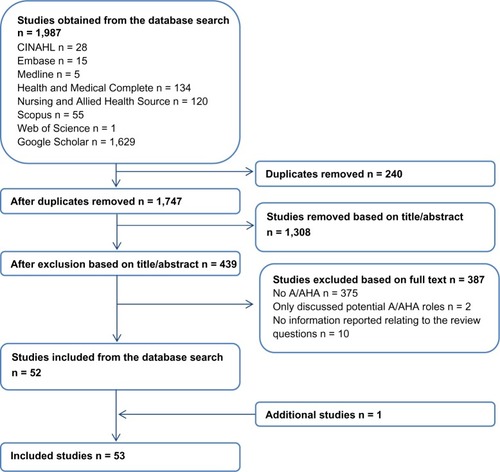

Of the 1,987 studies identified through searching of the database/Google Scholar, 52 were included, with one additional studyCitation7 meeting the inclusion criteria already known to the authors also included (see for the flow chart). reports the A/AHA roles reported in the literature, as well as the countries in which they have been implemented.

Figure 1 Flow chart for database search.

Table 2 Advanced allied health assistant terms used and the countries in which advanced allied health assistants work

Question 1: what is the scope of practice of A/AHAs?

Allied health disciplines

A/AHAs work in a range of disciplines, including pharmacy, social work, psychology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, podiatry, and dietetics (see ). Some studiesCitation8–Citation13,Citation16–Citation20,Citation22–Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation31–Citation33,Citation36,Citation37 did not report which allied health discipline the assistant worked in; however, they were included in this review because they did not clearly state that they were supporting a role outside of the allied health professions (eg, medical). This section of the review was informed by 33 studies; however, none of these studies specifically researched the disciplines, so these data cannot be allocated to the hierarchy of evidence.

Table 3 Allied health disciplines in which advanced allied health assistants work

Competencies

A qualitative studyCitation7 (NHMRC level not assigned) reported the competencies required of an extended role occupational therapy support worker. These were the ability to make sound judgments, interpersonal skills (eye contact, “nice disposition”, friendly), interest in the job, communication skills, confidence, need to be able to assert their own role boundaries/competence/confidence, drive, have developed the role themselves, assertiveness, initiative, ability to “think outside the box”, need for self-direction, trustworthy (more than just a police check), ability to think/reflect on role, type of people who will continually improve (eg, undertake training), experience, training to underpin competence, formal qualifications, willing to accept responsibility, willing to learn, and clinical competence.Citation7

Tasks performed and level of autonomy

The tasks performed by A/AHAs, including their level of autonomy, are reported in . This section drew upon 22 studies; however, only one studyCitation44 (cross-sectional cohort, NHMRC level III-3) investigated the advanced tasks being performed by A/AHAs.

Table 4 Tasks performed by advanced allied health assistants

Question 2: what client groups do A/AHAs work with?

Twenty-six studies reported the client groups in which A/AHAs worked, but none of these studies investigated this, so no study was allocated to the NHMRC hierarchy of evidence. A/AHAs work with both adults and children with a range of conditions, including intellectual/learning disabilities, emotional, behavioral, and/or social difficulties, neurologic conditions, dementia, cancer, post-surgery (including total hip replacement), mental health problems, mobility problems, and those at risk of falls (see ).

Table 5 Client groups that advanced allied health assistants work with

Question 3: what settings do A/AHAs work in?

A/AHAs work in various settings, including clients’ homes, community services, and hospitals (see ). All data reported for this question were regarded as providing background information (ie, not from the research findings) for 30 studies, and were therefore not allocated to the hierarchy of evidence.

Table 6 Work settings of advanced allied health assistants

Question 4: what training is available for A/AHAs?

Formal training

In Australia, the Certificate IV in Allied Health Assistance was reported as a formal qualification for A/AHAs (one study,Citation38 background information, NHMRC level not assigned). Further, a Certificate IV level qualification in Hospital/Health Services Pharmacy Support was held by some of the pharmacy technicians/assistants in O’Leary’sCitation44 study (cross-sectional cohort, NHRMC level III-3), but not all of them, highlighting the inconsistencies in the level of education required to undertake these advanced roles.

In the United Kingdom, expanded role occupational therapy support workers/advanced practitioners had completed National Vocational Qualification training.Citation7 However, there was a perception reported in this qualitative study (NHMRC level not assigned) that a number of the skills/attributes that the A/AHA requires could only be gained through experience, rather than the formal “paper” qualification.Citation7

Informal training

Informal training for A/AHAs was also reported in two studiesCitation46,Citation55 (background information, NHRMC level not assigned). For advanced practice pharmacy technicians, a self-learning package was used and was developed inhouse.Citation46 Informal training for both advanced practice pharmacy technicians and senior pharmacy technicians involved competency assessments.Citation46,Citation55

Question 5: how effective are A/AHA roles in terms of health, cost, and process outcomes?

Process outcomes and stakeholder perspectives (relating to health and processes) were reported in four studies,Citation7,Citation38,Citation46,Citation55 but no study reported cost or health outcomes. The main findings were that the A/AHA role appears to be well accepted by clients, provides clients with more therapy time, and frees up time for allied health professionals to perform other duties. The details of the effectiveness of A/AHA roles are reported in . It should be noted that none of these studies were of high-level design. Consequently, there are inherent biases in the study designs, which reduce the believability of these findings.

Table 7 Key findings regarding the effectiveness of advanced allied health assistant roles

Question 6: what are the workforce issues for A/AHA?

Two qualitative studiesCitation7,Citation38 (NHMRC level not assigned) reported the issues associated with implementing A/AHA roles. A key issue was the uncertainty of the scope of practice of A/AHA,Citation7,Citation38 concerns relating to how they should be best utilized,Citation38 as well as issues around responsibility and accountability.Citation7,Citation38 In some cases, the allied health professionals had to spend more time supervising and training the A/AHA in the initial stages.Citation38 One studyCitation7 reported both undersupervision and oversupervision of the A/AHA, which may have been due to lack of understanding of the A/AHA role and the training provided to these assistants. Specific to the advanced community rehabilitation assistant role, time management was an issue because the A/AHA had to report to and communicate with a range of supervisors.Citation38 Some allied health professionals felt that the A/AHA were a cheap alternative to their own role;Citation7 however, in another study,Citation38 an A/AHA felt that their remuneration was insufficient given the additional responsibility of the role. These factors need to be considered in implementing A/AHA roles.

Discussion

This systematic review is the first investigating the roles, implementation, and effectiveness of A/AHAs. This review therefore provides the first high-level synthesis of literature, providing a greater overview of the scope and effectiveness of the A/AHA role than the primary literature. The published research is low-level (NHMRC level III-3 or not assigned), and for some research questions there were few relevant studies identified, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from this review. This lack of evidence highlights the need for greater research into the area of A/AHA roles.

A/AHA roles are diverse in terms of the disciplines they work with, as well as their work settings, tasks, and titles. This diversity presents challenges in defining such a role, and therefore providing appropriate training for these roles. A/AHA roles are likely to have emerged within a specific health service to meet unique needs, thus leading to ambiguity in what the role actually entails. This is not unique to A/AHA, given that systematic reviews regarding AHA roles have also reported this diversity.Citation2 The inconsistencies in how AHA roles are defined also has potential implications for defining the A/AHA roles, given that what may be considered an advanced role in one health service may be considered an AHA role in another. This has potential implications for this review, considering that studies had to identify the role as being advanced, extended, or senior to meet the inclusion criteria; hence studies of AHAs which may be considered advanced in some settings may have been missed.

In implementing A/AHA roles, stakeholder perspectives have been positive and the roles have been effective in terms of process outcomes, although evidence is low-level. There is currently no evidence regarding the effectiveness of these roles in impacting health or cost outcomes, presenting a clear evidence gap. All included studies regarding the effectiveness of A/AHA compared them with health professionals, rather than with AHAs. Hence the value of implementing A/AHA roles over AHA roles has not been determined. This reveals another area for future research.

A number of issues were reported in terms of fitting the new A/AHA roles into traditional health care models. Prior to implementation, the potential impact on other staff should be considered; strategies should be put in place to ensure that the A/AHAs are appropriately trained, supervised, and utilized within the health care system they are working in; and the level of responsibility and accountability of A/AHAs and the supervising allied health professionals needs to be established.

As with any change in the health care system, potential legal issues must also be considered. This was not discussed in implementation of A/AHA roles in any of the included studies. These requirements are likely to differ depending on location, the professions involved, the tasks being performed, and the level of autonomy and accountability assumed by the A/AHA. It should be noted that advanced practice roles by definition are still within the scope of practice of AHAs and are therefore unlikely to have significant legal implications. However, the legal issues would have to be considered carefully before any exploration of extended-scope tasks for AHAs.

Conclusion

This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, which has specifically investigated the roles of A/AHAs. The conclusions drawn are limited, due to the quality (low-level designs used, qualitative studies) and quantity of research evidence. Despite this, A/AHA roles are being established in Australia and internationally. These roles are diverse and welcomed by consumers, and there is some suggestion that they are effective in terms of process and health outcomes. Further research in the area should aim to understand the roles better and conduct higher-level studies to determine their effectiveness, particularly in terms of health and cost outcomes. This would enable policy-makers to determine the value of these roles, and how best to utilize them.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Leanne Pagett and Karen Murphy (ACT Health Directorate) for their assistance in developing the project, Karen Grimmer (International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, University of South Australia) for her assistance in developing the search strategy, and Saravana Kumar (International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, University of South Australia) for assisting in the drafting of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Australian Physiotherapy AssociationPosition statement: scope of practiceAustralian Physiotherapy Association Available from: http://www.physiotherapy.asn.au/DocumentsFolder/Advocacy_Position_Scope_of_Practice_2009.pdfAccessed November 21, 2011

- LizarondoLKumarSHydeLSkidmoreDAllied health assistants and what they do: a systematic review of the literatureJ Multidiscip Healthc20103143115321197363

- LoweJGrimmer-SomersKKumarSYoungAAllied health scope of practice role development in the wider allied health service delivery context: the allied health assistant (AHA)Prepared for the SA Health and Community Services Skills Board, Government of South Australia2008 Available from http://www.health.sa.gov.au/DesktopModules/SSSA_Documents/LinkClick.aspx?tabid=46&table=SSSA_Documents&field=ItemID&id=874&link=T%3A%5C_Online+Services%5CWeb+Admin%5CIndividual_site_correspondence%5CProject+Correspondence%5CAllied+Health%5CAsAccessed September 30, 2013

- National Health and Medical Research CouncilNHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines: stage 2 ConsultationNational Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/guidelines/stage_2_consultation_levels_and_grades.pdfAccessed January 18, 2013

- University of OxfordCentre for Evidence Based Medicine Systematic Review Critical Appraisal SheetCentre for Evidence Based Medicine, University of Oxford Available from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1157Accessed February 25, 2013

- The George Institute for Global HealthPEDro Scale. PEDro Physiotherapy Evidence Database Available from: http://www.pedro.org.au/english/downloads/pedro-scale/Accessed February 25, 2013

- NancarrowSMackeyHThe introduction and evaluation of an occupational therapy assistant practitionerAustralian Occupational Therapy Journal200552293301

- BradshawJGoldbartJStaff views on the importance of relationships with knowledge developmentJ Appl Res Intellect Disabil20132628429823386258

- StimpsonAKroeseBSMacMahonPThe experiences of staff taking on the role of lay therapist in a group-based cognitive behavioural therapy anger management intervention for people with intellectual disabilitiesJ Appl Res Intellect Disabil201326637023255379

- RavouxPBakerPBrownHThinking on your feet: understanding the immediate responses of staff to adults who challenge intellectual disability servicesJ Appl Res Intellect Disabil20122518920222489031

- RobertsonJPCollinsonCPositive risk taking: whose risk is it? An exploration in community outreach teams in adult mental health and learning disability servicesHealth Risk Soc201113147164

- HawkinsRRedleyMHollandADuty of care and autonomy: how support workers managed the tension between protecting service users from risk and promoting their independence in a specialist group homeJ Intellect Disabil Res20115587388421726324

- BosworthMHoyleCDempseyMMResearching trafficked women on institutional resistance and the limits to feminist reflexivityQual Inq201117769779

- PhillipsNRoseJPredicting placement breakdown: individual and environmental factors associated with the success or failure of community residential placements for adults with intellectual disabilitiesJ Appl Res Intellect Disabil201023201213

- FramptonIMcarthurCCroweBLinnJLoveringKBeyond parent training: predictors of clinical status and service use two to three years after ScallywagsClin Child Psychol Psychiatry20081359360818927143

- LoveringKFramptonICroweBMoseleyABroadheadMCommunity-based early intervention for children with behavioural, emotional and social problems: evaluation of the Scallywags SchemeEmotional and Behavioural Difficulties20061183104

- ParsonsSDanielsHPorterJRobertsonCResources, staff beliefs and organizational culture: factors in the use of information and communication technology for adults with intellectual disabilitiesJ Intellect Disabil Res2008211933

- CampbellMCognitive representation of challenging behaviour among staff working with adults with learning disabilitiesPsychol Health Med20071240742017620205

- HegartyJRAspinallAThe use of personal computers with adults who have developmental disability: outcomes of an organisation-wide initiativeThe British Journal of Development Disabilities200652137154

- HawkinsSAllenDJenkinsRThe use of physical interventions with people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour – the experiences of service users and staff membersJ Appl Res Intellect Disabil2005181934

- TurbettCRural social work in Scotland and eastern Canada: A comparison between the experience of practitioners in remote communitiesInt Soc Work200649583594

- WilsonESeymourJAubeeluckAPerspectives of staff providing care at the end of life for people with progressive long-term neurological conditionsPalliat Support Care2011937738522104413

- BeacroftMDoddKPain in people with learning disabilities in residential settings – the need for changeBritish Journal of Learning Disabilities201038201209

- LoweKJonesEHorwoodSThe evaluation of periodic service review (PSR) as a practice leadership tool in services for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviourTizard Learning Disability Review2010151728

- KroeseBSRoseJHeerKO’BrienAMental health services for adults with intellectual disabilities – what do service users and staff think of them?J Appl Res Intellect Disabil20132631323255374

- PlathDOrganisational processes supporting evidence-based practiceAdm Soc Work201337171188

- KleinbergISciorKThe impact of staff and service user gender on staff responses towards adults with intellectual disabilities who display aggressive behaviourJ Intellect Disabil Res1162012 [Epub ahead of print.]

- SawyerA-MMental health workers negotiating risk on the frontlineAustralian Social Work200962441459

- BroadheadMChiltonRStephensVUtilising the Boxall profile within the Scallywags service for children with emotional and behavioural difficultiesBritish Journal of Special Education2011381927

- BroadheadMHockadayAZahraMFrancisPCrichtonCScallywags – an evaluation of a service targeting conduct disorders at school and at homeEducational Psychology in Practice200925167179

- LawrenceVBanerjeeSImproving care in care homes: a qualitative evaluation of the Croydon care home support teamAging Ment Health20101441642420455117

- RobertsDHurstKEvaluating palliative care ward staffing using bed occupancy, patient dependency, staff activity, service quality and cost dataPalliat Med20122712313022687349

- BartlettAClarkeBAn exploration of health care professionals’ beliefs about caring for older people dying from cancer with a coincidental dementiaDementia201211559565

- DrydenHAddicottREvaluation of a pilot study day for health care assistants and social care officersInt J Palliat Nurs20091561119234424

- NazarkoLFalls Part 4: prevention, assessment and interventionBritish Journal of Health Care Assistants20082535539

- IrelandSLazarTMavrakCDesigning a falls prevention strategy that worksJ Nurs Care Qual20102519820720535846

- FordMTTetrickLERelations among occupational hazards, attitudes, and safety performanceJ Occup Health Psychol201116486621280944

- WoodAJSchuursSBAmstersDIEvaluating new roles for the support workforce in community rehabilitation settings in QueenslandAust Health Rev201135869121367337

- DrummondACooleCBrewinCSinclairEHip precautions following primary total hip replacement: a national survey of current occupational therapy practiceBr J Occup Ther201275164170

- YipK-SMedicalization of social workers in mental health services in Hong KongBritish Journal of Social Work200434413435

- YipK-SControversies in psychiatric services in Hong Kong: social workers’ superiority and inferiority complexesInt Soc Work200447240258

- GrahamHImplementing integrated treatment for co-existing substance use and severe mental health problems in assertive outreach teams: training issuesDrug Alcohol Rev20042346347015763751

- MasseyBFJrFor the sake of our patients, it is the right thing to doPhys Ther2005851238124216253051

- O’LearyKMTwo national surveys of hospital pharmacy technician activities to support the review of national qualificationsJournal of Pharmacy Practice and Research2012424347

- MaslankaELeachHJExpanding the role of a pharmacy technician in a private hospitalJournal of Pharmacy Practice and Research200434131132

- McKeeJZimmermanMTech-check-tech pilot in a regional public psychiatric inpatient facilityHosp Pharm201146501511

- NiazkhaniZPirnejadHvan der SijsHAartsJEvaluating the medication process in the context of CPOE use: the significance of working around the systemInt J Med Inform20118049050621555237

- HallKWRaymondCBWoloschukDMHoncharikNOrganizational restructuring of regional pharmacy services to enable a new pharmacy practice modelCan J Hosp Pharm20116445145622479101

- HonC-YTeschkeKChuaPVennersSNakashimaLOccupational exposure to antineoplastic drugs: identification of job categories potentially exposed throughout the hospital medication systemSaf Health Work2011227328122953211

- LeeSGAmbadosFTkaczukMNJankewiczGJPaclitaxel exposure and its effective decontaminationJournal of Pharmacy Practice and Research200939181185

- TkaczukMLeeSGJankewiczGAmbadosFSurface contamination of cytotoxic drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and decontaminationJournal of Health, Safety and Environment201026171181

- DugganCMooneyCRobertsPBecoming a good leader – developing the skills requiredHospital Pharmacist200714193194

- HerreraHFoundation degrees – building on the foundation of experienceHospital Pharmacist20071311312

- ConroySApplebyKBostockDUnsworthVCousinsDMedication errors in a children’s hospitalPaediatr Perinat Drug Ther200781825

- HoldingDStarting a pharmacy technician-led drug roundHospital Pharmacist200411477478

- OrchistonMCoordinating a medical gases serviceHospital Pharmacist200310324327

- TempestAAuditing the recording of allergy status in community hospitalsHospital Pharmacist200613259260

- SedgwickTImproving medicines management for older patients on the moveHospital Pharmacist200613226228

- MoulderBWhy not ask a technician to promote better prescribing?Hospital Pharmacist200411397398

- SiangCSNiKMbin RamliMNOutpatient prescription intervention activities by pharmacists in a teaching hospitalMalaysian Journal of Pharmacy200318690