Abstract

Background

In this study, we investigated primary care physicians’ exercise habits, and the association of this variable with their age, specialty, and workplace.

Methods

The population of this cross-sectional study comprised 3,310 medical doctors who graduated from Jichi Medical University in Japan between 1978 and 2012. The study instrument was a self-administered questionnaire mailed in August 2012 to investigate primary care physicians’ exercise habits, age, specialty, and workplace.

Results

The 896 available primary care physicians’ responses to the self-administered questionnaire were analyzed. Their exercise frequency was as follows: daily, 104 (11.6%); at least 2–3 times per week, 235 (26.2%); no more than once a week, 225 (25.1%); no more than once a month, 278 (31.0%); and other, 52 (5.8%). Their exercise intensity was as follows: high (≥6 Mets), 264 (29.5%); moderate (4–6 Mets), 199 (22.2%); mild, (3–4 Mets), 295 (32.9%); very mild (<3 Mets), 68 (7.6%); none, 64 (7.1%); and other, 6 (0.7%). Their exercise volume was calculated to represent their exercise habits by multiplying score for exercise frequency by score for intensity. Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that the primary care physicians’ exercise volumes were associated with their age (P<0.01) and workplace (P<0.01), but not with their specialty (P=0.37). Primary care physicians in the older age group were more likely to have a higher exercise volume than those in the younger age groups (50–60 years > older than 60 years >40–50 years >30–40 years >24–30 years). Primary care physicians working in a clinic were more likely to have a higher exercise volume than those working in a university hospital, polyclinic hospital, or hospital.

Conclusion

Primary care physicians’ exercise habits were associated with their age and workplace, but not with their specialty.

Introduction

Exercise has a positive impact on total morbidity and mortality, and can also prevent many chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, chronic kidney disease, arthritis, obesity, and depression.Citation1–Citation8 Several exercise guidelines recommend at least 2.5 hours of exercise per week.Citation9–Citation14 Primary care physicians have an important role in exercise counseling because they manage patients at the front line. Exercise counseling by primary care physicians has been reported to improve patients’ exercise habits.Citation15 Several studies have also reported that primary care physicians’ own lifestyles may influence the lifestyle counseling that they offer to patients.Citation16–Citation19 These lines of evidence suggest that primary care physicians’ exercise habits are important for both their own health and when counseling patients about exercise. However, details concerning the exercise habits of primary care physicians have not been previously reported. Therefore, we tried to clarify whether primary care physicians take good care of themselves by exercising. In addition, given that primary care physicians vary with regard to age, specialty, and workplace, we investigated the relationship between exercise habits and age, specialty, and workplace in a large population (n=3,310) of medical doctors.

Subjects and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by a member of the ethics committee of Jichi Medical University.

Subjects

The study population comprised 3,310 medical doctors who graduated from Jichi Medical University in Japan between 1978 and 2012. Medical doctors who graduate from this university have a 5–7-year obligation to work in a rural area of Japan as primary care physicians. Most (>80%) continue to work as primary care physicians after this term of duty.

Study instrument

The study instrument was a self-administered questionnaire designed to obtain detailed information about specific characteristics of primary care physicians, including their age, specialty, workplace, personal exercise habits, exercise counseling for patients with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, and management of chronic kidney disease (exercise counseling practice, medical prescription pattern). The results concerning their exercise counseling of patients with metabolic syndrome and/or cardiovascular disease and management of chronic kidney disease will be analyzed and reported elsewhere. The parameters canvassed in the questionnaire along with the response options were as follows:

Age (24–30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, or ≥60 years)

Specialty (internal medicine, surgery, general medicine, pediatrics, other)

Workplace (university hospital, polyclinic hospital, hospital, clinic, other [including health facilities for recuperation])

Weekly frequency of exercise sessions lasting 30 minutes (daily, at least 2–3 times per week, no more than once a week, no more than once a month, other)

Intensity of exercise (high [≥6 Mets], eg, swimming, jogging, soccer, cycling; moderate [4–6 Mets], eg, quick walking, golf; mild [3–4 Mets], eg, walking, cleaning; very mild [<3 Mets], eg, stretching, cooking; none; other).

Exercise volume

Exercise volume was calculated to represent exercise habits by multiplying the score for exercise frequency by the score for exercise intensity. The frequency of exercise sessions lasting at least 30 minutes was scored as follows: daily, 3.5 (7 days × 0.5 hours); at least 2–3 times/week, 1.25 (2.5 days × 0.5 hours); no more than once a week 0.5 (one day × 0.5 hours), no more than once a month, or 0.125 (0.25 days × 0.5 hours). Exercise intensity was scored as follows: high, 6 (6 Mets); moderate, 5 (5 Mets); mild, 4 (4 Mets); very mild, 3 (3 Mets); or none, 0 (0 Mets). Answers marked “other” for exercise frequency (n=52) and exercise intensity (n=6) were excluded from evaluation of exercise volume because they could not be scored.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The associations between primary care physicians’ exercise volume and their age, specialty, and workplace were analyzed by multiple linear regression analysis to determine the independent variables. SPSS Statistics version 21 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The survey was mailed to 3,310 medical doctors, with responses received from 933 (28.2%). Thirty-seven responses were excluded for lack of completeness in terms of information supplied regarding age group, specialty, and workplace. The remaining 896 responses to the self-administered questionnaire were analyzed. As shown in , the primary care physicians’ age, specialty, and workplace data were as follows:

Table 1 Characteristics of primary care physicians

Age (24–30 years, 75 [8.4%]; 30–40 years, 273 [30.5%]; 40–50 years, 284 [31.7%]; 50–60 years, 249 [27.8%]; and ≥60 years, 15 [1.7%])

Specialty (internal medicine, 412 [46.0%]; surgery, 168 [18.8%]; general medicine, 163 [18.2%]; pediatrics, 45 [5.0%]; other, 108 [12.1%])

Workplace (university hospital, 108 [12.1%]; polyclinic hospital, 201 [22.4%]; hospital, 256 [28.6%]; clinic, 288 [32.1%]; other, 43 [4.8%]).

Primary care physicians’ exercise habits

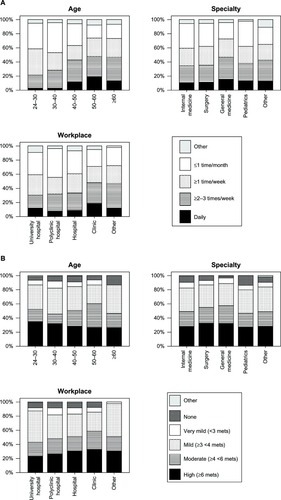

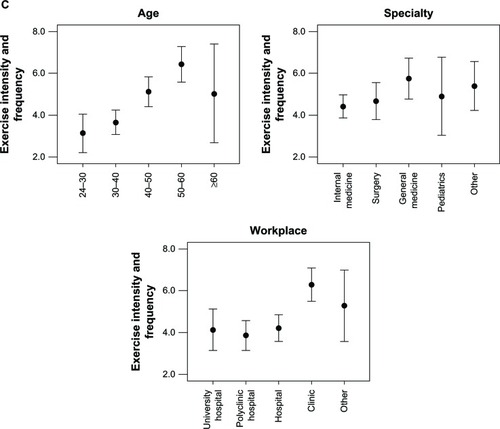

The primary care physicians’ exercise frequency was as follows: daily, 104 (11.6%); at least 2–3 times per week, 235 (26.2%); at least once a week, 225 (25.1%); no more than once a month, 278 (31.0%); or other, 52 (5.8%, ). Their exercise intensity was as follows: high (≥6 Mets), 264 (29.5%); moderate (4–6 Mets), 199 (22.2%); mild (3–4 Mets), 295 (32.9%); very mild (<3 Mets) 68 (7.6%); none, 64 (7.1%); or other, 6 (0.7%, ). Exercise frequency and intensity categorized by age, specialty, and workplace are shown in and . Mean exercise volume categorized by age, specialty, and workplace was as follows:

Figure 1 (A) Associations of primary care physicians’ exercise frequency and their age, specialty, and workplace. (B) Asociations of primary care physicians’ exercise intensity and their age, specialty, and workplace. (C) Associations of primary care physicians’ exercise volume and their age, specialty, and workplace.

Table 2 Primary care physicians’ own exercise habits

Age (24–30 years, 3.12 ± 3.88; 30–40 years, 3.65 ± 4.78; 40–50 years, 5.12 ± 5.84; 50–60 years, 6.43 ± 6.42; and ≥60 years, 5.03 ± 4.43)

Specialty (internal medicine, 4.42 ± 5.41; surgery, 4.67 ± 5.56; general medicine, 5.75 ± 6.06; pediatrics, 4.90 ± 6.21; or other, 5.39 ± 5.75)

Workplace (university hospital, 4.14 ± 4.90; polyclinic hospital, 3.86 ± 4.99; hospital, 4.21 ± 4.90; clinic, 6.29 ± 6.64; and other, 4.85 ± 5.66).

Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that the primary care physicians’ age (P<0.01) and workplace (P<0.01) were associated with their exercise volume ( and ). However, their specialty was not associated with their exercise volume (P=0.37, and ). Primary care physicians in the older age group were more likely to have a higher exercise volume than their younger counterparts (50–60 years > older than 60 years >40–50 years >30–40 years >24–30 years). Primary care physicians working in a clinic were more likely to have a higher exercise volume than those working in a university hospital, polyclinic hospital, or hospital.

Table 3 Multivariate linear regression analyses of the association between primary care physicians’ own exercise habits (exercise volume) and their age, specialty, and workplace

Discussion

In the present study, the exercise habits of primary care physicians were significantly associated with their age and workplace, but not with their specialty. Their age group was positively associated with their exercise habits. Those in the older age group were likely to do more exercise than those in the younger age groups (50–60 years > older than 60 years >40–50 years >30–40 years >24–30 years). Primary care physicians working in a clinic were more likely to have better exercise habits than those working in a university hospital, polyclinic hospital, or hospital. These results may be explained by primary care physicians in the older age groups and those working in clinics taking better care of their own health and being able to make time available for exercise than younger doctors working in a university hospital, polyclinic hospital, or hospital. Many physical activity guidelines include recommendations regarding exercise.Citation9–Citation14 US physical activity guidelines recommend at least 2.5 hours a week of moderate intensity physical activity, such as brisk walking.Citation9 The UK physical activity guidelines also recommend at least 2.5 hours of moderate intensity activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more.Citation14 The committee of Ministry of Health, Labour and welfare of Japan recommends 23 Mets-hours (Mets multiple hours) per week of exercise with an intensity >3 Mets.Citation12 The exercise frequency of many primary care physicians in the present study did not reach the recommended levels; about 50% of the respondents reported an exercise frequency of less than once a week (no more than once a week, 25.1%; no more than once a month, 31.0%). Their exercise intensity likely reached the recommended levels because over 80% of primary care physicians reported an exercise intensity above 3 Mets (≥6 Mets, 29.5%; 4–6 Mets, 22.2%; 3–4 Mets, 32.9%). Several studies have reported that physicians’ lifestyles may influence the lifestyle counseling they offer to patients.Citation16–Citation19 Kawakami et al reported that physicians who smoked themselves were less likely to recommend that patients stop smoking than those who did not smoke.Citation17 Abramson et al reported that physicians who exercised regularly were more likely to counsel their patients on the benefits of exercise.Citation16 These lines of evidence suggest that improvement of lifestyle, including exercise habits, may contribute positively to not only primary care physicians’ own health but also their health counseling of patients. Therefore, encouragement of primary care physicians to undertake exercise seems to be important for public health. Considering that the level of exercise performed by primary care physicians in the present study did not reach that recommended in the current exercise guidelines, greater encouragement of doctors to exercise is necessary.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the study instrument was a mailed self-administered questionnaire, which raises the issue of self-selection bias and could also have contributed to the low response rate (28.2%). Second, the primary care physicians in this study may not be representative of the entire population of primary care physicians, because all had graduated from the same university. Third, it should be noted that the results of this study were from a self-administered questionnaire, and therefore do not reflect an objective evaluation of primary care physicians’ actual exercise habits. Finally, primary care physicians’ reports of their own behavior may not always be accurate.Citation20 Further studies will be needed to investigate the actual exercise habits of primary care physicians using instruments such as exercise recording devices.

In conclusion, primary care physicians’ exercise habits were found to be inadequate in this study, and were significantly associated with age and workplace, but not with specialty.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Minami Watanabe, Yuko Suda, Yukari Hoshino, and Aiko Oashi for their assistance with this research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BlairSNKampertJBKohlHW3rdInfluences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and womenJAMA199627632052108667564

- BoydenTWPamenterRWGoingSBResistance exercise training is associated with decreases in serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in premenopausal womenArch Intern Med19931531971008422204

- ClyneNThe importance of exercise training in predialysis patients with chronic kidney diseaseClin Nephrol200461Suppl 1S10S1315233242

- GoldbergLElliotDLThe effect of physical activity on lipid and lipoprotein levelsMed Clin North Am198569141553883078

- KriskaAMBlairSNPereiraMAThe potential role of physical activity in the prevention of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the epidemiological evidenceExerc Sport Sci Rev1994221211437925541

- UnderwoodFBLaughlinMHSturekMAltered control of calcium in coronary smooth muscle cells by exercise trainingMed Sci Sports Exerc19942610123012387799766

- PaffenbargerRSJrLeeIMLeungRPhysical activity and personal characteristics associated with depression and suicide in American college menActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl199437716228053361

- PaffenbargerRSJrHydeRTWingALHsiehCCPhysical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumniN Engl J Med1986314106056133945246

- [No authors listed]Physical activity guidelines for AmericansOkla Nurse200853425

- [No authors listed]Abstracts of the 2005 Australian Conference of Science and Medicine in Sport, 5th National Physical Activity Conference, 4th National Sports Injury Prevention ConferenceJ Sci Med Sport20058Suppl 41124416416566

- TremblayMSWarburtonDEJanssenINew Canadian physical activity guidelinesAppl Physiol Nutr Metab2011361364621326376

- KawakuboKPhysical activity and healthy Japan 21Nihon Rinsho200058Suppl532537 Japanese11085172

- MisraANigamPHillsAPConsensus physical activity guidelines for Asian IndiansDiabetes Technol Ther2012141839821988275

- DunlopMMurrayADMajor limitations in knowledge of physical activity guidelines among UK medical students revealed: implications for the undergraduate medical curriculumBr J Sports Med2013471171872023314886

- LogsdonDNLazaroCMMeierRVThe feasibility of behavioral risk reduction in primary medical careAm J Prev Med1989552492562789846

- AbramsonSSteinJSchaufeleMFratesERoganSPersonal exercise habits and counseling practices of primary care physicians: a national surveyClin J Sport Med2000101404810695849

- KawakamiMNakamuraSFumimotoHTakizawaJBabaMRelation between smoking status of physicians and their enthusiasm to offer smoking cessation adviceIntern Med19973631621659144005

- ShermanSEHershmanWYExercise counseling: how do general internists do?J Gen Intern Med1993852432488505682

- WellsKBLewisCELeakeBWareJEJrDo physicians preach what they practice? A study of physicians’ health habits and counseling practicesJAMA198425220284628486492364

- McPheeSJRichardRJSolkowitzSNPerformance of cancer screening in a university general internal medicine practice: comparison with the 1980 American Cancer Society guidelinesJ Gen Intern Med1986152752813772615