Abstract

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) infection may be associated with damage to the spinal cord – HTLV-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis – and other neurological symptoms that compromise everyday life activities. There is no cure for this disease, but recent evidence suggests that physiotherapy may help individuals with the infection, although, as far as we are aware, no systematic review has approached this topic. Therefore, the objective of this review is to address the core problems associated with HTLV-1 infection that can be detected and treated by physiotherapy, present the results of clinical trials, and discuss perspectives on the development of knowledge in this area. Major problems for individuals with HTLV-1 are pain, sensory-motor dysfunction, and urinary symptoms. All of these have high impact on quality of life, and recent clinical trials involving exercises, electrotherapeutic modalities, and massage have shown promising effects. Although not influencing the basic pathologic disturbances, a physiotherapeutic approach seems to be useful to detect specific problems related to body structures, activity, and participation related to movement in HTLV-1 infection, as well as to treat these conditions.

Introduction

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) is a retrovirus of the Retroviridae family that affects T-lymphocytes from human blood and can cause neurological disorders.Citation1,Citation2 The distribution of this retrovirus in the world has an irregular shape. Although prevalence in Africa and India is not yet fully known, it is believed that there are now 5 to 10 million people infected worldwide, with the main endemic areas being southwest Japan, sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Caribbean, and places in the Middle East, Australia, and Melanesia.Citation3,Citation4

In Brazil, the geographical distribution of the infection is quite heterogeneous, and the country can be seen as one of the most endemic areas,Citation3 with an assumed 2.5 million people living with HTLV.Citation5 The highest number of cases are in the northeast, southeast, and north regions, and Salvador city has the highest prevalence (1.7%). Women are primarily infected, especially those of low educational and socioeconomic levels.Citation5,Citation6

Of individuals infected by HTLV-1, only 4% to 5% develop HTLV-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) in the fourth or fifth decade of life, which in Brazil is the principal progressive myelopathy due to non-tumoral causes.Citation6 Although the pathogenesis of HAM/TSP remains uncertain, the disease process is understood as demyelization and axonal degeneration that result from an inflammatory reaction in the region infiltrated by mononuclear cells, with destruction of the white and gray matter of the spinal cord, leading to reduced sensory and motor capacities associated with functional consequences.Citation7,Citation8 All these results lead to impairments in body structures, activity, and social participation.

HAM/TSP is characterized by the classic symptoms of progressive weakness and chronic pain in the lower back and lower limbs, urinary urgency, spasticity, hyperreflexia (which may be present in all four limbs), the Babinski sign, and abnormalities of superficial and deep sensibility of the lower limbs.Citation7 Other symptoms may also be associated, like erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, urinary incontinence, and constipation.Citation9,Citation10

Many patients need adaptations for daily activities of living, such as crutches, walkers, braces, and wheelchairs, which are associated with increased physical handicap, risk of falls, and reduced quality of life and work capacity.Citation7 Living with this disease may generate social isolation and depression.Citation11 All these features correlate with those of patients with similar neuro-functional conditions in who good results are obtained through physiotherapy.Citation12

Although physiotherapy cannot directly affect the pathological aspects of the infection, it can make a significant contribution to the care of these patients, as the desired clinical outcomes of chronic diseases are improvement in functional status, symptom reduction, and a positive impact on quality of life. However, there is little evidence regarding specific physiotherapy programs for individuals with this disease. Therefore, the aim of this narrative review is to present the principal problems associated with HTLV-1 that can be treated with physiotherapy and the results of clinical trials, indicating perspectives for the development of knowledge in this area.

Physiotherapeutic assessment of individuals with HTLV-1

Although physiotherapy is a relatively new profession, having emerged after World War II, it is distinguished from other health professions because of its specific study of human movement and function, as well as its use of physical resources to provide modifications to the body’s structures, activity, and social participation.Citation13 Through a functional kinetic diagnosis and therapeutic modalities, including manual therapy, therapeutic exercise, electrotherapy, thermotherapy, phototherapy, hydrotherapy, and other physical resources, physiotherapy is a profession that has a significant role in the multidisciplinary health team, and meets specific is particularly suited to the needs of the individual with HTLV-1. The exclusive use of drug or surgical interventions cannot address the biopsychosocial model of health care proposed by the World Health Organization.Citation14

Each health professional evaluates individuals from a particular point of view, and therefore develops a broad range of methods for the diagnosis and monitoring of therapeutic interventions. Some instruments have been developed to assess general conditions, being useful for all professionals and applicable to individuals with different clinical conditions.Citation15,Citation16 Others are specific, and skilled professionals from certain areas are more likely to use them with greater precision.Citation17,Citation18 As they are specific, only a few individuals with certain diseases or dysfunctions may benefit from their use. Due to the imprecision of assessment tools, the biological variability of affected individuals, and the intrinsic subjectivity of the human being,Citation19,Citation20 it is important to know the best resources to assess and treat each condition.

Assessment of sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic assessment of patients infected by HTLV-1 may involve consideration of characteristics such as age and sex, since the prevalence tends to increase over the years of life and women are the most affected.Citation3 Aspects such as socioeconomic and educational levels should be taken into consideration in the evaluation due to the epidemiological profile that has been reported.Citation21,Citation22 Additional factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, job satisfaction, and physical activity were not clearly associated with HTLV-1, but may be associated with secondary findings or progression of symptoms and motor performance.

Assessment of pain and sensory abnormalities

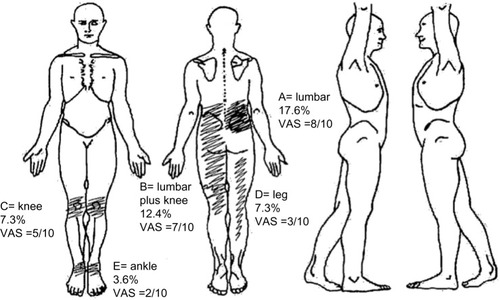

Pain is one of the principal complaints of patients with HTLV-1Citation2,Citation7 and is in general a chronic condition, with a high impact on the patients’ quality of life.Citation21,Citation22 Importantly, individuals infected with HTLV-1, even when still asymptomatic for neurological symptoms (neurogenic bladder or HAM/TSP), have twice the prevalence of chronic pain in relation to a noninfected population.Citation22 Therefore, this symptom should be evaluated in detail and monitored at all stages of the disease (), and may be due to neuropathic and nociceptive sources, as well.Citation2,Citation21,Citation22

Figure 1 This figure presents a typical body map, with the location of pain sites ordered by importance (not always pain severity) according to the patients, from A to E, pain frequency and intensity in the visual analog scale (VAS).

People with chronic pain should be evaluated in terms of: its location (using a body map, featuring all presenting pain); its type – if neuropathic, nociceptive, mixed, or with characteristics of centralization; its intensity (visual analog scale is the most common method of assessing this); attenuating/provoking factors (description, triggering and mitigating factors); its duration in months or years; the drugs that are or were used to control it; the impact on the patient’s quality of life (qualitative and/or quantitative assessment); and some cognitive-behavioral aspects that may interfere, such as the level of catastrophizing thoughts, quality of sleep, beliefs about pain, anxiety and depression, among others. Due to the multidimensionality of pain, at least three valid instruments should be applied to its assessment before and after the interventions, even in research.Citation20

The physiotherapist will be better able to assess the behavior of symptoms regarding all aspects of movement, with the focus on identifying dysfunction, as well as musculoskeletal or neurophysiological abnormalities that may be causing the symptoms.Citation20 Among the questionnaires available, use of at least the Brief Pain Inventory is recommended.Citation23 This questionnaire combines the use of a visual scale with a body map and considers the duration of symptoms, including those that are sensory and cognitive, and the impact of pain on personal life. The instrument has the capability to evaluate the structural levels of, and also activity and participation related to, pain – a key factor, as in chronic pain conditions there is often a disproportion between symptom intensity and functionality.Citation24

To distinguish the type of pain, whether nociceptive or neuropathic, the Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) questionnaireCitation25 is a simple and quick tool. It is important to consider that pain in these patients is not exclusively neuropathic, since in a study, 52.6% of study participants had six or more sites of pain in the body, and in many of them, the characteristic was predominantly nociceptive, with no association between location and type of pain.Citation21,Citation22 After filling in the body map, identifying the type of pain in each of the affected sites can help the therapist to seek distinct sources of the symptom. Nociceptive pain is usually referred at secondary areas, whereas neuropathic pain symptoms are more frequently located at the site of lesion. These differences are consequent to distinct patterns of descending inhibition and facilitation from brain stem.Citation26 This phenomenon will lead to a trend of complaints about regions that are distant from the source of the symptoms, and not those where the lesion is localized. Interestingly, for neuropathic pain, it is the opposite, with pain being indicated as being at the same location as the lesion. Therefore, identification of the type of pain will help the clinician to look at the actual source of symptoms.

To assess the impact on quality of life, despite the fact that the Short-Form 36 Quality of Life Questionnaire (SF-36)Citation21,Citation22,Citation24 is the most applied instrument, the short version of the World Health Organization of Quality of Life (WHOQOL)Citation27 questionnaire can be used in less time and is more easily understood by individuals with different educational levels, including those of low socioeconomic status.Citation5,Citation6 The factors that most impact the quality of life of these patients are pain and functional independence,Citation24 which should be evaluated in more detail.

Quantitative sensory testing can complement some subjective findings regarding pain or even other sensory changes in patients with HTLV-1, which include changes in tactile, mechanical, and thermal thresholds, and reduction in vibration and proprioceptive sensibility. For simple quantitative sensory evaluation, instruments such as a pressure gauge (algometer), Von Frey filaments (five to 20 graduated nylon filaments), and a calibrated brush can be used.Citation28,Citation29 The places most affected by pain and sensory changes are the lower back and lower limbs, due to spinal-cord lesions.Citation17 Therefore the assessment should follow the key points recommended in the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale for tactile (including protopathic and epicritic touch), thermal, and pain sensibilities.Citation30 Changes in superficial sensibility in patients with HTLV-1 include hypo (hypoesthesia) or hyper phenomena (hyperalgesia, allodynia, and hyperpathia). Pressure pain threshold can also be assessed in the spinous processes of the lumbar spine, seeking to verify if there is hyperalgesia due to local or regional inflammatory processes.Citation28

Deep sensibility abnormalities include a decrease in proprioception and vibratory sensibility, both present in patients with HAM/TSP.Citation7,Citation8 To assess vibratory sensibility, a 64/128 Hz tuning fork should be used, and the tests should be made on the bony protuberances of the lower limbs, including the anterior superior iliac spine, greater trochanter of the femur, patella, medial and lateral malleolus, and heads of the first and fifth metatarsals.Citation29 The physiotherapist must include in the proprioceptive evaluation the impact of the changes in motor function, especially balance, gait, and transfers.Citation17

HTLV-1 may be associated with peripheral nerve injuriesCitation2,Citation8 and so the therapist should consider that the pattern of sensory and motor impairments may be due to this type of injury, and not only from the spinal-cord injury. Besides the distribution of the symptoms being longitudinal to the limbs, and non-transverse, this type of injury often exhibits a typical mechanical behavior – neurodynamics, which can be detected by maneuvers that put pressure or tension on the peripheral nerves.Citation31 Although this has not yet been determined in individuals infected with HTLV-1, the maneuvers that put tension on the spinal cord and in the peripheral nerves, like the sciatic, fibular, sural, and femoral nerves, must be considered in the evaluation.Citation32 If symptoms are reproduced with these maneuvers, the patient is likely to benefit from neural mobilization.

Evaluation of motor function

To evaluate the static and dynamic motor function it is important to use tools for kinematic and kinetic evaluation, specific functional tests, and validated and reliable questionnaires. Postural changes are frequent in these patients and a simple way to evaluate them has been described previously.Citation33 This method uses a simple camera and free two-dimensional motion analysis software – SAPO (Sistema de Avaliação Postural).Citation34 The typical posture of the patient with HAM/TSP is characterized by a tendency to flexion in the knees and ankles, associated with an anterior or posterior trunk tilt. These postural deviations may be due to shortening and stiffness of muscle groups formed by the flexors and hip adductors, knee flexors, and extensors of the ankle; weakness of flexors, extensors, abductors, and external rotators of the hip and knee extensors;Citation33 and weakness of gluteal and abdominal muscles, generating hip flexion, pelvic instability, and misalignment of the lower limbs.Citation35 All these disorders can cause joint deformities that impact significantly on the gait,Citation7 balance,Citation35 and posture.Citation33 Noteworthy is the loss of postural control due to proprioceptive impairment in HAM/TSP, which prevents the continual adjustments within the base of support to maintain mobility and increases the risk of falls.Citation12,Citation36

Use of photography and the SAPO protocol also allows for evaluation of the range of active movement, which can be complementary to passive goniometric evaluation, when necessary.Citation34 The range of motion assessments, including the final sensations of movement, will help the physiotherapist identify changes in muscle tonus and possible causes of limitations. Changes in tonus may be viscoelastic or neuromuscular.Citation37 The former is related to limitations of soft tissues such as joint capsules, ligaments, fascia, and muscles, and can lead to significant repercussions in global function. Spasticity is the typical abnormality in the tonus of individuals with HAM/TSP, and the Modified Ashworth Scale is the most widely used for quantification.Citation38

To assess the strength, specific and universal dynamometers are advantageous.Citation17 Due to changes in the strength found in spastic muscles,Citation2,Citation35 and the typical posture and pain pattern in patients with HAM/TSP,Citation33 it is recommended at least the strength assessment of the erector spinae muscles, knee extensors and flexors, and calf, as well as flexors, extensors, abductors, and external rotators of the hips be undertaken. A more complete assessment of the lower limbs may provide additional data that can help establish a more precise treatment program. When the initial evaluation does not result in an effective treatment, more advanced resources such as surface electromyography or musculoskeletal ultrasound can help determine altered patterns of muscle activation.Citation17,Citation39 These types of assessment may be especially beneficial in the control of lower back pain of nociceptive origin in these individuals.

To assess gait and balance, especially in individuals with neurological disorders, the most useful methods are the Timed Up and Go (TUG)Citation40 test and the Berg Balance Scale.Citation41 Despite the fact that the use of the Berg Scale is not reported in patients with HAM/TSP, a recent study demonstrated that at baseline they present much lower grades than those found in elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease and stroke.Citation42 The use of other scales has also been suggested, such as the adaptation of the scale used in paraplegiaCitation18 and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM),Citation35 which can extend the functionality evaluation. The use of more precise measures such as a three-dimensional kinematic dispositive, isokinetic dynamometry, and stabilometry can improve the accuracy of kinetic functional diagnosis,Citation17,Citation39 but involve more extensive assessments and more expensive resources.

Assessment of bowel and vesicourethral function

The Osame Motor Disability Score (OMDS), regardless of it being a general tool, is also used to assess urinary function, grading levels of continence and incontinence, residual sensation, and voiding frequency.Citation10 Quality of life related to urinary dysfunction may be also assessed through specific questionnaires on urinary symptoms, and perineal detailed physical evaluation favors the proper choice of individualized therapeutic resources.Citation9

The thoracic and lumbosacral segments of the spinal cord are the principal sites of injury in patients with radiographic findings of spinal-cord atrophy.Citation43,Citation44 The inflammatory process interrupts the connection of the sacral cord levels S2 to S4 and pudendal nerve to the sacral and pontine micturition center.Citation9 The sacral centers start to behave in a reflexive way, with inadequate storage and bladder symptoms of urinary loss.Citation9,Citation44

In the course of the disease, detrusor-sphincter hyperreflexia and bladder sphincter dyssynergia prevail, which need to be confirmed by urodynamic study. It is common to find urgency, urge incontinence, nocturia, urinary frequency, and symptoms of hesitancy, weak or intermittent stream, sensation of incomplete emptying, stress voiding, and urinary retention.Citation44 The presence of vesico-sphincter dyssynergia and areflexia can be found even in individuals with HTLV-1 but without HAM/TSP.Citation7,Citation10,Citation43 As a consequence, lower urinary tract and intravesical hyperpressure arises, which in severe cases leads to impaired kidney function.Citation2,Citation9 These physiological changes in urination are one of the biggest factors of morbidity.Citation10

Neurogenic bowel is also part of the picture presented by individuals infected with HTLV-1, and consists of the loss of sensation of the need for evacuation or the inability to distinguish between the presence of solid or liquid stool, and/or gas in the rectum. The intestinal dysfunctions may be associated with constipation and/or fecal incontinence. Though the former is the most often reported symptom, both bring a lot of discomfort and disorder that impact the quality of life for these individuals.Citation44

Evidence for physiotherapeutic treatment

Having made an accurate diagnosis, the next step consists of prescribing a treatment. Applying interventions in these individuals without a more accurate physiotherapeutic diagnosis is often dangerous, because even with positive intention to treat, some features may be harmful, since the clinical picture is very complex.Citation7 For this reason, physiotherapy should move toward evidence-based and patient-centered clinical practice ().

Table 1 Physiotherapeutic assessment and treatment of individuals with human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1)

As far as we are aware, to date, few studies have considered the results of physiotherapy interventions in individuals infected with HTLV-1, and specifically with HAM/TSP. However, despite the fact that they are preliminary, the existent findings point to a positive path that can aid in the relief of symptoms and improvement of functional clinical signs in individuals affected by this disease.

Exercise and manual therapy

Physical exercises have the best results in the perception of the subjects treated, and in the evolution of the measured objective data. The use of a simple protocol of only six functional exercises (using stairs, standing on tiptoes, squatting, sitting, and standing) demonstrated a positive impact on functionality with reduced risk of falling rated by the FIM and TUG test.Citation45 Positive response was also observed in all parameters of health-related quality of life, with decreased pain intensity, in patients who underwent a protocol using classic Pilates exercises performed on equipment with springs.Citation46 In another study, patients who underwent exercise with the help of a Nintendo Wii showed improved balance and emotional aspects of quality of life.Citation42

Perineal exercises can be used for overactive bladder, with the goal of reflex inhibition of the detrusor by voluntary contractions of the external urethral sphincter, facilitating voiding control. When indicated, increased pelvic muscle strength improves urethral closure pressure and stress, reducing losses. Stimuli such as the Credé and Valsalva maneuvers, and massage of the genitalia or inner thigh region are indicated when there are no signs of bladder sphincter dyssynergia, abnormal pressure, or abnormal emptying.Citation47,Citation48 All these methods are aimed at improving urinary storage at low pressures, and establishing continence to preserve kidney function and improve quality of life for patients. Perineal exercises, manual therapy techniques, anal relaxation, and abdominal massage to facilitate colonic transit may also help.Citation49 Results seem to show positive effects of massage on bowel function in patients with HAM/TSP.Citation50

Electrotherapy

Electrotherapy involves a number of features that can be useful in the treatment of individuals infected with HTLV-1 in many of its phases. As far as we are aware, only one study has been done to investigate the control of pain with transcranial direct current stimulation, and this showed a reduction in intensity of symptoms in just two sessions.Citation51 However, after the third session the control group showed similar results to the group receiving active electrostimulation, raising doubts that the results were due to the electrotherapy – the improvement in both groups may indicate patients’ positive expectancy with the application of electrotherapeutic resources, and therefore different models should be tested.

Other forms of electrotherapy involving muscle contraction to reduce spasticity and increase strength and motor control have shown promising results in a number of myelopathies,Citation52 and should be considered in future studies of individuals with HTLV-1. Although it has not been tested in these patients, perineal electrostimulation at low frequencies generates suppression of efferent activity in the pelvis through central inhibition, physiologically activates the inhibitory reflex, decreases the number of delayed urinations, increases bladder capacity, and reduces the symptoms of urgency and urge incontinence.Citation53 It may also be useful in restoring the sensation of bladder filling.Citation54,Citation55

Cognitive-behavioral strategies

Limited mobility and the sometimes low socioeconomic status of infected individuals have stimulated the search for protocols that can be performed autonomously in the patient’s home. Our group developed a handbook of home exercises that is being tested in a randomized clinical trial.Citation56 The proposal consists of a training intervention group opting for the model of health education.Citation57 In this model, the individuals become active subjects in the learning process, being recognized as carriers of knowledge no less important than the technical-scientific knowledge of the investigator/health care professional.Citation57 The interaction between individuals and staff begins via a focus group, which enables the strengthening of ties, and a survey on the participants’ expectations regarding home exercise programs and perceptions on the benefits achieved by performing such exercises.

Behavioral therapy, in the form of a voiding diary – which aims to guide voiding control and changes in lifestyle, and balance water and food intake – may also be useful in the treatment of neuropathic bladder.Citation48 Coloproctological physiotherapy can also make use of behavioral therapy, to advise individuals regarding a balanced diet and proper hydration to improve bowel function.Citation49

Final considerations

HTLV-1 infection can lead to a diverse clinical picture and tends to be chronic. Actually there is no cure for this infection, and physiotherapy may have an important role in managing individuals with this infection, due to its neurological manifestations. The limited specific evidence in this area shows that there is the potential to use a physiotherapeutic approach in the care of individuals with HTLV-1, mainly to control pain, to improve movement, urinary symptoms, and quality of life. Future studies are needed both on the delineation of the functional consequences of HTLV-1 and its treatment by physiotherapy, which should be included in health care plans for individuals with this condition.

Authors’ contributions

Katia N Sá idealized the project. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in either drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PoieszBJRuscettiFWGazdarAFBunnPAMinnaJDGalloRCDetection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphomaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19807712741574196261256

- AraujoAQSilvaMTThe HTLV-1 neurological complexLancet Neurol20065121068107617110288

- GessainACassarOEpidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infectionFront Microbiol201215338823162541

- HlelaCShepperdSKhumaloNPTaylorGPThe prevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 in the general population is unknownAIDS Rev200911420521419940947

- Carneiro-ProiettiABCatalan-SoaresBCCastro-CostaCMHTLV in the Americas: challenges and perspectivesRev Panam Salud Publica2006191445316536938

- MoxotoIBoa-SorteNNunesCSociodemographic, epidemiological and behavioral profile of women infected with HTLV-1 in Salvador, Bahia, an endemic area for HTLVRev Soc Bras Med Trop20074013741 Portuguese17486251

- ReissDBFreitasGSBastosRHNeurological outcomes analysis of HTLV-1 seropositive patients of the Interdisciplinary Research HTLV Group (GIPH) cohort, BrazilRetrovirology201411Suppl 1P51

- YamanoYSatoTClinical pathophysiology of human T-lymphotropic virus-type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesisFront Microbiol20129338923162542

- DinizMSFeldnerPCCastroRASartoriMGGirãoMJImpact of HTLV-I in quality of life and urogynecologic parameters of women with urinary incontinenceEur J Obst Gynecol Reprod Biol2009147223023319733955

- AndradeRTanajuraDSantanaDSantosDdCarvalhoEMAssociation between urinary symptoms and quality of life in HTLV-1 infected subjects without myelopathyInt Braz J Urol201339686186624456778

- GascónMRCapitãoCGCassebJNogueira-MartinsMCSmidJOliveiraACPrevalence of anxiety, depression and quality of life in HTLV-1 infected patientsBraz J Infect Dis201115657858222218518

- TysonSFConnellLAHow to measure balance in clinical practice. A systematic review of the psychometrics and clinical utility of measures of balance activity for neurological conditionsClin Rehabil200923982484019656816

- CavalcanteCCRodriguesARDadaltoTVda SilvaEBEvolução científica da fisioterapia em 40 anos de profissão [The scientific evolution of the Brazilian physical therapy in 40 years as a profession]Fisioterapia em Movimento2011243513522 Portuguese

- World Health Organization (WHO)The Ottawa Charter for Health PromotionOttawaWHO1986 Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/Accessed November 4, 2014

- BerkmanNDSheridanSLDonahueKEHealth literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic reviewEvid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep)2011199194123126607

- McPheetersMLKripalaniSPetersonNBClosing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science (vol 3: quality improvement interventions to address health disparities)Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep)20122083147524422952

- RicciNAArataniMCCaovillaHHCohenHSGanançaFFEvaluation of properties of the Vestibular Disorders Activities of Daily Living Scale (Brazilian version) in an elderly populationBraz J Phys Ther201418217418224676704

- AdryRALinsCCKruschewsky RdeACastro FilhoBGComparison between the spastic paraplegia rating scale, Kurtzke scale, and Osame scale in the tropical spastic paraparesis/myelopathy associated with HTLVRev Soc Bras Med Trop201245330931222760127

- de PaulaJJBertolaLde ÁvilaRTDevelopment, validity, and reliability of the General Activities of Daily Living Scale: a multidimensional measure of activities of daily living for older peopleRev Bras Psiquiatr201436214315224554276

- DeSantanaJMSlukaKAPain assessmentSlukaKAMechanisms and Management of Pain for the Physical TherapistSeattle, WAIASP Press200995131

- NetoECBritesCCharacteristics of Chronic Pain and its impact on quality of life of patients with HTLV-1-associated Myelopathy/Tropical Spastic Paraparesis (HAM/TSP)Clin J Pain201127213113520842011

- MendesSMBaptistaAFSáKNPain is highly prevalent in individuals with tropical spastic paraparesisHealth Care2013134753

- MemóriaCMYassudaMSNakanoEYForlenzaOVBrief screening for mild cognitive impairment: validation of the Brazilian version of the Montreal cognitive assessmentInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2013281344022368034

- MartinsJVBaptistaAFAraújo AdeQQuality of life in patients with HTLV-I associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesisArq Neuropsiquiatr201270425726122323336

- SantosJGBritoJOde AndradeDCTranslation to Portuguese and validation of the Douleur Neuropathique 4 questionnaireJ Pain201011548449020015708

- VanegasHSchaibleHGDescending control of persistent pain: inhibitory or facilitatory?Brain Res Brain Res Rev200446329530915571771

- ZimpelRRFleckMPQuality of life in HIV-positive Brazilians: application and validation of the WHOQOL-HIV, Brazilian versionAIDS Care200719792393017712697

- RolkeRMagerlWCampbellKAQuantitative sensory testing: a comprehensive protocol for clinical trialsEur J Pain2006101778816291301

- ShyMEFrohmanEMSoYTTherapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyQuantitative sensory testing: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology200360689890412654951

- KirshblumSCBurnsSPBiering-SorensenFInternational standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011)J Spinal Cord Med201134653554622330108

- ButlerDSMobilisation of the Nervous SystemLondonChurchill Livingstone1991

- EllisRFHingWANeural mobilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials with an analysis of therapeutic efficacyJ Man Manip Ther200816182219119380

- MacêdoMCBaptistaAFSáKNPostural Profile of Individuals with HAM/TSPBraz J Med Human Health20132199110

- FerreiraEADuarteMMaldonadoEPBurkeTNMarquesAPPostural assessment software (PAS/SAPO): Validation and reliabiliyClinics201065767568120668624

- FranzoiACArauújoAQDisability profile of patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM)Spinal Cord200543423624015520834

- FacchinettiLDAraújoAQChequerGLde AzevedoMFde OliveiraRVLimaMAFalls in patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP)Spinal Cord201351322222523165507

- SimonsDGMenseSUnderstanding and measurement of muscle tone as related to clinical muscle painPain19987511179539669

- PisanoFMiscioGDel ConteCPiancaDCandeloroEColomboRQuantitative measures of spasticity in post-stroke patientsClin Neurophysiol200011161015102210825708

- HamanoTFujiyamaJKawamuraYMuscle MRI findings of HTLV-1-associated myelopathyJ Neurol Sci20021991454812084441

- MetsavahtLLeporaceGRibertoMTranslation and cross-cultural adaptation of the lower extremity functional scale into a Brazilian Portuguese version and validation on patients with knee injuriesJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2012421193293923047028

- PangMYEngJJFall-related self-efficacy, not balance and mobility performance, is related to accidental falls in chronic stroke survivors with low bone mineral densityOsteoporos Int200819791992718097709

- ArnaultVSáKNUso do Nintendo Wii em pacientes com HAM/TSP: Ensaio clinico randomizado [Use of Nintendo Wii in patients with HAM/TSP: randomized clinical trial]Masters thesisSalvadorBahian School of Medicine and Human Health2014

- CastroNMFreitasDMRodriguesWJrMunizAOliveiraPCarvalhoEMUrodynamic features of the voiding dysfunction in HTLV-1 infected individualsInt Braz J Urol200733223824517488545

- RochaPNRehemAPSantanaJFThe cause of urinary symptoms among Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type I (HLTV-I) infected patients: a cross sectional studyBMC Infect Dis20071271517352816

- ThoméBIBorguiISBerardiJMoserADAssisGMFisioterapia na reeducação do intestino neurogênico como resultado de uma lesão medular [Physiotherapy in the rehabilitation of neurogenic bowel as a result of a spinal cord injury]Manual Therapy, Posturology and Rehabilitation Journal201210471927 Portuguese

- NetoIFMendonçaRPNascimentoCAMendesSMSáKNFortalecimento muscular em pacientes com HTLV-1 e sua influência no desempenho funcional: um estudo piloto [A pilot study: muscle strengthening in patients with HTLV-1 and its influence on functional performance]Revista Pesquisa em Fisioterapia201222143155 Portuguese

- BorgesJBaptistaAFSantanaNPilates exercises improve low back pain and quality of life in patients with HTLV-1 virus: a randomized crossover clinical trialJ Bodyw Mov Ther2014181687424411152

- SkaudickasDKėvelaitisEModern approach to treatment of urinary incontinenceMedicina (Kaunas)2010467496503 Lithuanian20966624

- MesquitaLACésarPMMonteiroMVSilva FilhoALTerapia comportamental na abordagem primária da hiperatividade do detrusor [Behavior therapy in primary approach of the detrusor’s overactivity]Femina20103812329 Portuguese

- LiuZSakakibaraROdakaTMechanism of abdominal massage for difficult defecation in a patient with myelopathy (HAM/TSP)J Neurol2005252101280128215895308

- SoutoGBorgesICGoesBTEffects of tDCS-induced motor cortex modulation on pain in HTLV-1: a blind randomized clinical trialClin J Pain201430980981524300224

- MorawietzCMoffatFEffects of locomotor training after incomplete spinal cord injury: a systematic reviewArch Phys Med Rehabil201394112297230823850614

- TeriLGibbonsLEMcCurrySMExercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2003290152015202214559955

- AmarencoGIsmaelSSEven-SchneiderAUrodynamic effect of acute transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in overactive bladderJ Urol200316962210221512771752

- PrimusGKramerGPummerKRestoration of micturition in patients with acontractile and hypocontractile detrusor by transurethral electrical bladder stimulationNeurourol Urodyn19961554894978857617

- BorgesAMSalícioVAGonçalvesMALovatoMA contribuição do fisioterapeuta para o programa de saúde da família – uma revisão da literature [The contribution of the physical therapist for the family health program – a literature review]Uniciências20101416982 Portuguese

- AlvesVSUm modelo de educação em saúde para o Programa Saúde da Família: pela integralidade da atenção e reorientação do modelo assistencial [A health education model for the Family Health Program: towards comprehensive health care and model reorientation]Interface – Comunicação, Saúde e Educação20059163952 Portuguese