Abstract

Background

Mammography screening for women under the age of 50 is controversial. Groups such as the US Preventive Services Task Force recommend counseling women 40–49 years of age about mammography risks and benefits in order to incorporate the individual patient’s values in decisions regarding screening. We assessed the impact of a brief educational intervention on the knowledge and attitudes of clinicians regarding breast cancer screening.

Methods

The educational intervention included a review of the risks and benefits of screening, individual risk assessment, and counseling methods. Sessions were led by a physician expert in breast cancer screening. Participants were physicians and nurses in 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics in Alabama. Outcomes were as follows: 1) knowledge assessment of mammogram screening recommendations; 2) counseling practices on the risks and benefits of screening; and 3) comfort level with counseling about screening. Outcomes were assessed by survey before and after the intervention.

Results

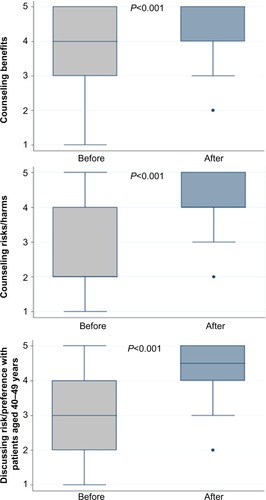

After the intervention, significant changes in attitudes about breast cancer screening were seen. There was a decrease in the percentage of participants who reported that they would screen all women ages 40–49 years (82% before the intervention, 9% afterward). There was an increase in the percentage of participants who reported that they would wait until the patient was 50 years old before beginning to screen (12% before the intervention, 38% afterward). More participants (5% before, 53% after; P<0.001) said that they would discuss the patient’s preferences. Attitudes favoring discussion of screening benefits increased, though not significantly, from 94% to 99% (P=0.076). Attitudes favoring discussion of screening risks increased from 34% to 90% (P<0.001). The comfort level with discussing benefits increased from a mean of 3.8 to a mean of 4.5 (P<0.001); the comfort level with discussing screening risks increased from 2.7 to 4.3 (P<0.001); and the comfort level with discussing cancer risks and screening preferences with patients increased from 3.2 to 4.3 (P<0.001). (The comfort levels measurements were assessed by using a Likert scale, for which 1= not comfortable and 5= very comfortable.)

Conclusion

Most clinicians in the US Department of Veterans Affairs ambulatory practices in Alabama reported that they routinely discuss mammography benefits but not potential harms with patients. An educational intervention detailing recommendations and counseling methods affected the knowledge and attitudes about breast cancer screening. Participants expressed greater likelihood of discussing screening options in the future.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of terminal cancer among women in the United States,Citation1 and it is the most frequent cause of death by cancer for women in less developed regions.Citation2 Mammography is routinely utilized to screen women in order to reduce their risk of death from breast cancer. However, mammography screening is also associated with inherent risks, specifically harms related to false positive screening and overdiagnosis.Citation3

Mammography screening programs appear to confer a mortality benefit; however, this benefit is age dependent.Citation3–Citation5 Out of 2,000 women ages 40–49 screened biannually for 10 years, one death would be avoided at a cost of $105,000 per life year saved. For women ages 50–59, four out of 2,000 would benefit with a cost of $21,000 per life year saved. This increases to six lives saved for women in their 60s at the same cost.Citation5,Citation6

Potential harms from mammography include pain from the screening procedure itself, radiation exposure, false positive results (which may lead to unnecessary procedures and psychological stress), and overdiagnosis of breast cancer.Citation4 Overdiagnosis (disease that would have never been evident in the patient’s lifetime) is the reason for an estimated 15%–25% of cancers identified by screening. At this rate, 6–10 women out of every 2,500 screened are at risk for overdiagnosis.Citation7 The risk of false positives and overdiagnosis is higher when younger women are screened and when screening is done annually. In a recent meta-analysis, Welch and Passow report that 510–690 out of 1,000 women in their 40s screened annually over a 10-year time period may have a false positive mammogram. They estimate the risk of overdiagnosis to be up to eleven per 1,000 women receiving yearly screening in this age group.Citation3

The American Cancer Society,Citation8 The American College of Radiology,Citation9 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network,Citation10 and The American College of Obstetrics and GynecologistsCitation11 recommend mammogram screening beginning at age 40. However, since evidence suggests that younger women may have a lower benefit–risk ratio, other groups in the United States, Canada, and Europe recommend that women at average risk wait until age 50 to be screened.Citation12–Citation15 A recent update from the World Health Organization recommends that screening of women ages 40–49 be a shared decision based on the patient’s values and preferences.Citation16 Likewise, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that mammography screening of women in this age group take into consideration the “patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms”.Citation12

Mammography screening rates remain unchanged in recent years, a finding which suggests that practice patterns have not incorporated options to postpone screening.Citation17 Women indicate that they desire to be actively involved in decision-making regarding medical testing related to breast health.Citation18 However, research has shown that providers do not typically include women in decision-making about screening. Lack of time, language barriers, and lack of knowledge are cited as reasons for not discussing these issues.Citation19 Patients report that they typically receive information on the benefits of mammography screening but rarely receive information regarding the harms.Citation20

Clinicians need to assist patients in weighing the benefits and the potential harms of screening. Therefore, it is important to clarify advantages and disadvantages of screening options in order to support patients in the determination of best actions according to their individual risks and preferences. Health care professionals are expected to provide patients with clear information about all of their health issues in order to engage them in shared decision-making about their medical care.Citation21 As primary care moves toward a patient-centered, interdisciplinary team model, nonphysician team members are often tasked with discussing and ordering screening tests.Citation22 Therefore, the education of the entire health care team on current breast cancer screening guidelines and counseling methods is an important step in achieving success in this area.

The objectives of our study were as follows: 1) to assess the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care providers’ and staffs’ reported practices regarding counseling women on potential benefits and harms of breast cancer screening and 2) to assess the impact of a brief educational intervention on VA providers’ and staffs’ knowledge, attitude, and comfort level regarding counseling on the pros and cons of breast cancer screening.

Methods

We used a quasiexperimental design with participant surveys conducted before and after an educational intervention. All surveys were anonymous. The educational intervention consisted of a 30-minute academic detailing session for all physicians and nursing staff in 13 community-based primary care VA clinics in the state of Alabama from June 2012 to September 2012. Participants were instructed on USPSTF guidelines, which are the standards mandated by the Veterans Health Administration.Citation23 In addition, the benefits and harms of mammography screening,Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation12 risk assessment tools,Citation24,Citation25 and counseling methodsCitation26 were discussed. The same speaker facilitated all sessions, and the same material was presented to each group. The speaker was a general internist with proficiency in providing care to women; in addition, she has 20 years of experience in education of medical students, physicians, and nursing staff.

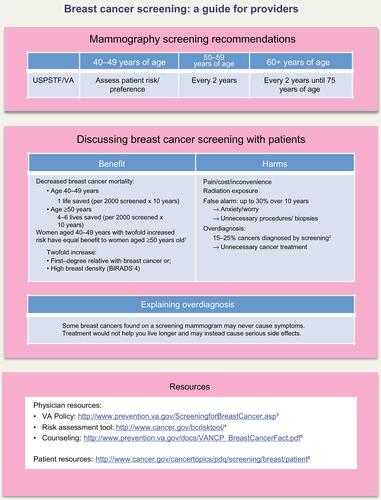

Teaching sessions focused on USPSTF recommendations because providers in the VA primary care clinics (our study group) are expected to adhere to these guidelines.Citation23 A poster summarizing these recommendations was given to each clinic for future reference (Figure S1).

In addition, material from the lecture was also made available for future access in the Clinician Guide: Discussing Breast Cancer Screening Decisions with Average Risk Women in Their 40s.Citation26 This guide was developed by the National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Office of Patient Care Services, Veterans Health Administration.

Pre- and post-training surveys were used to assess these outcomes: 1) knowledge of breast cancer screening guidelines; 2) counseling practices of benefits and risks of screening; and 3) comfort level in providing counseling about risks and benefits of screening. Paper surveys were administered immediately before and after each teaching session. The participants were not matched in pre- and post-training surveys.

To assess knowledge of breast cancer screening guidelines, participants were asked how they would address screening mammography for average risk women ages 40–49. Participants were asked to choose from these options: 1) recommend mammogram screening; 2) recommend waiting until age 50 to start mammogram screening; and 3) recommend screening on the basis of patient preference.

To assess counseling practices of benefits and risks, participants were asked “Do you typically inform your patients of the benefits of mammography screening?” and “Do you typically inform your patients of the risks or harms of mammogram screening?”. Participants responded yes or no to both of these questions.

Finally, we asked participants how comfortable they were in providing counseling regarding screening benefits and risks/harms and in discussing cancer risks and preferences with women ages 40–49 for shared decision-making. (There were three questions asked; patients responded by using the five-point Likert scale, for which 1= not comfortable and 5= very comfortable.)

An exemption was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. The Institutional Review Board at our facility did not require informed consent to participate because the risk was no greater than those ordinarily encountered in daily life. The intervention was deemed an educational quality improvement project. Quality improvement consists of actions that intend to improve health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups.

Statistical analysis

We used standard descriptive statistics. To compare responses given before the intervention with those given after the intervention, we used the chi-square test for categorical data and the Mann–Whitney U test for ordinal data (comfort level), as data were not normally distributed. To illustrate differences in ordinal data (comfort level), we have presented the results in box plots. We used a P<0.05 to assess statistical significance. We used Stata 11.2 for analysis (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Thirteen outpatient VA clinics in Alabama received the educational intervention, which reached 87 out of a total of 121 staff members (physicians and nurses). There were 13 teaching sessions with an average of seven attendees at each session. A total of 165 surveys (78 before the intervention, 87 after the intervention) were received (nine participants did not complete the pretraining survey). The response rate was 90% for pretraining surveys and 100% for post-training surveys. Responders were registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, physicians, and nurse practitioners ().

Table 1 Professional degrees of the participants

Screening knowledge

Regarding the screening knowledge assessment, there were differences between the pre- and the post-intervention responses on breast cancer screening recommendations for 40–49 year old women. Before the intervention, 82.4% of participants reported that they would advise all women ages 40–49 to be screened; after the intervention, 8.6% of participants reported that they would give that advice. Before the intervention, 12.3% of participants reported that they would advise patients to wait until age 50 to be screened; that percentage increased to 38.3% after the intervention. The percentage of participants who said that they would discuss the patient’s preferences before making a screening decision increased from 5.3% before the intervention to 53.1% afterward. All differences were significant (P<0.001; ).

Table 2 Screening knowledge and counseling practices

Counseling practice

After the intervention, attitudes favoring discussion of risks of mammography increased from 33.8% to 90.5% (P<0.001). Attitudes favoring discussion of benefits of screening also trended upward from 93.5% to 98.8%; however, this was not statistically significant (P=0.076; ).

Comfort level with counseling and with eliciting patient preferences

After the intervention, the comfort level with all aspects of counseling improved: benefits of screening (P<0.001); risks and harms of screening (P>0.001); and eliciting the screening preferences for women 40–49 (P<0.001). shows these relationships in the top, middle, and bottom panels, respectively.

Figure 1 Outcomes. Comfort level with counseling on benefits, counseling on risks/harms, and discussing patient preference.

Discussion

Our study shows that physicians and nursing staff (including registered nurses and licensed practical nurses) practicing in 13 community-based VA clinics in Alabama routinely provide counseling on the benefits of mammography screening but not on the potential harms of such screening. In order for women to make informed decisions regarding breast cancer screening, this information needs to be available to them. Although it has been several years since USPSTF recommended counseling women ages 40–49 about the risks and benefits of mammography screening, we found that few providers adhere to this recommendation in practice. This is consistent with prior data that change in behavior often lags behind more recent evidence and guidelines.Citation27 Our study did not assess why providers do not discuss options with women. Previously reported reasons include disagreement with guidelines, lack of knowledge, and lack of time.Citation28

After the educational intervention, those stating they would counsel women 40–49 increased from 5% to 53%. However, 38% indicated they would not offer screening, or even discuss screening options, until patients reach age 50. Likewise, 9% indicated they would continue to recommend screening for all 40-year old women. This may reflect the fact that there is controversy regarding screening recommendations with other groups continuing to recommend to start screening all women when they reach age 40.Citation8–Citation11

It has been demonstrated that VA medical facilities have greater compliance with breast cancer screening quality indicators than do non-VA hospitals.Citation29 Our study took place in VA outpatient clinics that participate in a quality improvement system using computerized clinical reminders for preventive health. VA medical practitioners are likely to be influenced by prompts from these reminders. Some comments from our participants indicated that it was easier to order the mammogram and receive credit for the quality measure than to take additional steps to extend the reminder to age 50. This concern has also been voiced with regard to health policy in other countries. A publication from the UK calls for changing performance measures to assess informed choice rather than screening participation rates.Citation30 VA performance measures have been updated to offer more options for women ages 40–49; these new criteria include documentation of a discussion of risks and benefits of screening.Citation23 The Clinician GuideCitation26, discussed previously, is also available to review during the completion of computerized quality reminders. Ongoing policy and clinical reminder development for nursing and allied health staff may be helpful in supporting primary care team members as they undertake an active role in counseling about preventive health.

Strengths of our study include our sample of primary care providers and staff from 13 VA community-based clinics. This provides a picture of nonacademic settings and allows for the assessment of the entire interdisciplinary team. Clinic staff, rather than the physician, often assist in completion of preventive health maintenance, and they may be the team members who actually provide the counseling and order the screening test.Citation22 Hence, without involvement from the entire primary care team, efforts to accomplish counseling may be difficult. Therefore, clinic personnel need to be included in education around current guidelines, risk assessment, and counseling of patients.

There are limitations to our study. We did not compare the responses from particular staff members (physicians vs nonphysicians) or from different clinics. It is possible that some groups are more responsive to the intervention than are others, a variable which may allow for a change in approach in the future. In addition, our survey only assessed opinions and attitudes immediately after the intervention; we do not know if this will affect future clinical practice or if the change in attitudes and knowledge is sustainable. Future research will be needed to determine if actual practice patterns are influenced.

We found that most health care professionals’ opinions about counseling changed after receiving a brief educational intervention with information on guidelines and counseling methods. Our participants indicated that in the future they plan to counsel women in their 40s about their options for screening. This suggests that lack of awareness of screening guidelines and lack of knowledge regarding counseling techniques may be reasons why many providers do not offer this counseling. Therefore, academic sessions may be valuable for equipping clinicians with knowledge to enhance preventive services.

A combination of education, technology, and staff support is probably needed to increase the availability of counseling on screening options for women. A recent meta-analysis summarizes suggestions for evidence-based discussion points that are similar to our academic detailing for informed decision-making about mammography screening.Citation31 Likewise, a recent editorial by Esserman and O’Kane suggests that screening should be further refined by improved risk assessment and adjustment of biopsy thresholds; therefore, the standard guidelines should move away from “one size fits all” screening.Citation32 This more patient-centered approach will mean having more involved discussions with women about their options, but further research is needed to better understand whether these discussions affect outcomes.

Conclusion

Physicians and nursing staff in 13 outpatient VA primary care clinics in Alabama routinely discuss mammography benefits but not potential harms with women ages 40–49 prior to screening. An educational intervention detailing current breast cancer screening recommendations and counseling methods for this age group affected providers’ knowledge and attitudes toward screening. Hence, the delivery of patient-centered care may be enhanced by the education of the entire primary care team.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Women’s Health Education Innovation Grant 2012, awarded by the Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 The US Preventive Services Task Force breast cancer screening guide.

Note: This is adapted from the poster that was handed to each clinic after the educational intervention.

Abbreviations: BIRADS, Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- van RavesteynNTMigliorettiDLStoutNKTipping the balance of benefits and harms to favor screening mammography starting at age 40 years: a comparative modeling study of riskAnn Intern Med2012156960961722547470

- KalagerMAdamiHOBretthauerMTamimiRMOverdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer due to mammogram screening: results from the Norwegian screening programAnn Intern Med2012156749149922473436

- Veteran’s Hospital AdministrationVHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: Screening for Breast Cancer Washington, DCVeterans Health Administration2014 Available from the Veteran’s Administration IntranetAccessed December 24, 2014

- Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health Last updated 5/16/2011. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/Accessed March 23, 2015

- National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Office of Patient Care Services, Veterans Health AdministrationClinician Guide: Discussing Breast Cancer Screening Decisions with Average Risk Women in Their 40’sWashington, DCVeterans Health Administration2011 Available from: http://www.prevention.va.gov/docs/VANCP_BreastCancerFact.pdfAccessed December 24, 2014

- Breast Cancer Screening (PDQ®)National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health Last updated November 24, 2014. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/breast/patientAccessed March 23, 2014

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the University of Alabama in Birmingham, or the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

References

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010 [webpage on Internet]BethesdaNational Cancer Institute2012 [cited April 2013]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/Accessed July 20, 2014

- FerlayJSoerjomataramIErvikMGLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11[Internet]Lyon, FranceInternational Agency for Research on Cancer2013 Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/pages/fact_sheets_population.aspxAccessed March 23, 2015

- WelchHGPassowHJQuantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammographyJAMA Intern Med2014174344845324380095

- NelsonHDTyneKNalikAScreening for breast cancer: an update for the US Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med20091511072773719920273

- BarrattAHowardKIrwigLSalkeldGHoussamiNModel of outcomes of screening mammography: Information to support informed choicesBMJ2005330749793615755755

- SalzmannPKerlikowskeKPhillipsKCost-effectiveness of extending screening mammography guidelines to include women 40 to 49 years of ageAnn Intern Med1997127119559659412300

- KalagerMAdamiHOBretthauerMTamimiRMOverdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer due to mammogram screening: results from the Norwegian screening programAnn Intern Med2012156749149922473436

- SmithRAManassaram-BaptisteDBrooksDCancer Screening in the United States, 2014: A review of current American Cancer Society Guidelines and current issues in cancer screeningCA Cancer J Clin2014641305124408568

- LeeCHDershawDDKopansDBreast cancer screening with imaging: Recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging and the ACR on the use of mammography, breast MRI, breast ultrasound, and other technologies for the detection of clinically occult breast cancerJ Am Coll Radiol201071182720129267

- BeversTBAndersonBOBonaccioENCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosisJ Natl Compr Canc Netw20097101060109619930975

- American College of Obstetricians-GynecologistsPractice bulletin no 122: Breast cancer screeningObstet Gynecol20111182 Pt 137238221775869

- NelsonHDTyneKNaikABougatsosCChanBKHumphreyLUS Preventive Services Task ForceScreening for breast cancer: an update for the US Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med200915110727737W237W24219920273

- QaseemASnowVSherifKAronsonMWeisKBOwensDKScreening mammography for women 40 to 49 years of age: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of PhysiciansAnn Intern Med2007146751151517404353

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; TonelliMConnor GorberSJoffresMRecommendations of screening for breast cancer in average-risk women aged 40–74 yearsCMAJ2011183171991200122106103

- Advisory Committee on Cancer PreventionRecommendations on cancer screening in the European Union. Advisory Committee on Cancer PreventionEur J Cancer200036121473147810930794

- World Health OrganizationWHO Position Paper on Mammography ScreeningGenevaWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137339/1/9789241507936_eng.pdf?ua=1Accessed February 7, 2015

- PaceLEHeYKeatingNLTrends in mammography screening rates after publication of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendationsCancer2013119142518252323605683

- DaveyHMBarrattALDaveyEMedical tests: women’s reported and preferred decision-making roles and preferences for information on benefits, side-effects and false resultsHealth Expect20025433034012460222

- DunnASShridharaniKVLouWBernsteinJHorowitzCRPhysician-patient discussions of controversial cancer screening testsAm J Prev Med200120213013411165455

- Zikmund-FisherBJCouperMPSingerEDeficits and variations in patients’ experience with making 9 common medical decisions: the DECISIONS surveyMed Decis Making2010305 Suppl85S95S20881157

- CoulterAParsonsSAskhamJPolicy Brief: Where are the Patients in Decision-Making About Their Own Care?CopenhagenWorld Health Organization Regional Office for Europe2008 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/107980/1/E93419.pdf?ua=1Accessed February 7, 2015

- Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health AdministrationVHA Handbook 1101.10, Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) HandbookWashington, DCVeterans Health Administration2014 Available from: http://www1.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2977Accessed December 24, 2014

- Veteran’s Hospital AdministrationVHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: Screening for Breast CancerWashington, DCVeterans Health Administration2014 Available from the Veteran’s Administration IntranetAccessed December 24, 2014

- van RavesteynNTMigliorettiDLStoutNKTipping the balance of benefits and harms to favor screening mammography starting at age 40 years: a comparative modeling study of riskAnn Intern Med2012156960961722547470

- NelsonHDZakherBCantorARisk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Intern Med2012156963564822547473

- National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Office of Patient Care Services, Veterans Health AdministrationClinician Guide: Discussing Breast Cancer Screening Decisions with Average Risk Women in Their 40’sWashington, DCVeterans Health Administration2011 Available from: http://www.prevention.va.gov/docs/VANCP_BreastCancerFact.pdfAccessed December 24, 2014

- BerwickDMDisseminating innovations in health careJAMA2003289151969197512697800

- CabanaMDRandCSPoweNRWhy don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvementJAMA1999282151458146510535437

- Prevention – Breast Cancer Screening [webpage on Internet]Washington, DCUS Department of Veterans Affairs2012 Available from: http://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/initiatives/compare/prevention-breast-cancer-screening.aspAccessed December 24, 2014

- StrechDParticipation rate or informed choice? Rethinking the European key performance indicators for mammography screeningHealth Policy2014115110010324332817

- PaceLEKeatingNLA systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide breast cancer screening decisionsJAMA2014311131327133524691608

- EssermanLO’KaneMEMoving beyond the breast cancer screening debateJ Women’s Health (Larchmt)201423862963025068713