Abstract

Objective

The aims of this cross-sectional study were to investigate the usefulness of using an Internet survey of patients with fibromyalgia in order to obtain information concerning symptoms and functionality and identify clusters of clinical features that can distinguish patient subsets.

Methods

An Internet website has been used to collect data. Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised version, self-administered Fibromyalgia Activity Score, and Self-Administered Pain Scale were used as questionnaires. Hierarchical agglomerative clustering was applied to the data obtained in order to identify symptoms and functional-based subgroups.

Results

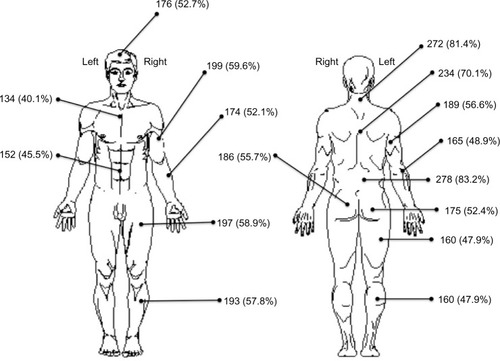

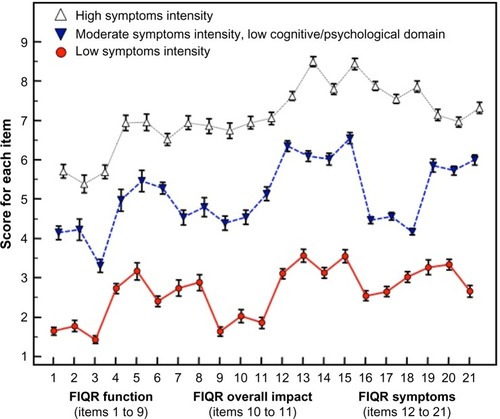

Three hundred and fifty-three patients completed the study (85.3% women). The highest scored items were those related to sleep quality, fatigue/energy, pain, stiffness, degree of tenderness, balance problems, and environmental sensitivity. A high proportion of patients reported pain in the neck (81.4%), upper back (70.1%), and lower back (83.2%). A three-cluster solution best fitted the data. The variables were significantly different (P<0.0001) among the three clusters: cluster 1 (117 patients) reflected the lowest average scores across all symptoms, cluster 3 (116 patients) the highest scores, and cluster 2 (120 patients) captured moderate symptom levels, with low depression and anxiety.

Conclusion

Three subgroups of fibromyalgia samples in a large cohort of patients have been identified by using an Internet survey. This approach could provide rationale to support the study of individualized clinical evaluation and may be used to identify optimal treatment strategies.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic heterogeneous syndrome that affects ~2%–3% of the general population.Citation1–Citation3 Its primary symptom is chronic, widespread pain associated with generalized tenderness on light palpation. Many patients report a multitude of additional complaints and symptoms,Citation4 including fatigue, exhaustibility and stiffness, and impaired concentration and memory (a complaint that is increasingly recognized as an independent symptom, namely, “fibrofog” or “dyscognition”, according to medical literature).Citation5 The combinations and severity of symptoms may vary from patient to patient, and this makes it difficult to understand the disease and the development of appropriate treatment strategies.Citation6 However, stratifying patients by cluster analysis into more homogeneous subgroups on the basis of their patient-relevant clinical features may help to overcome these limitations.Citation7–Citation14 Cluster analysis allows to identify clinical features and quantifies the importance of each cluster.Citation15,Citation16

A comprehensive assessment of main symptoms and the evaluation of the impact on the multidimensional aspects of function should be a routine part of patient care in FM. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are playing an increasingly significant role in the evaluation of symptoms, health-related quality of life, and medical compliance.Citation17 The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised version (FIQR) is currently the recommended tool for assessing function and health-related quality of life in patients with FM. FIQR assesses six domains (pain, tenderness, fatigue, stiffness, multidimensional function, and sleep) identified as core dimensions by Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials.Citation18 Psychometric properties of FIQR (ie, rating scale functioning, internal construct validity, reliability indices, and dimensionality) have been validated.Citation19,Citation20 Routine PROs collection can be facilitated by using more advanced interactive computer technologies such as Internet-based home telemonitoring and can support a transition from institution to patient-centered applications.Citation21–Citation26

The aims of this cross-sectional study were to investigate the usefulness of an Internet-based national survey of patients with FM in order to obtain information concerning symptoms and functionality and to identify clusters of symptoms that helps to distinguish patient subsets.

Methods

Study population

The participants were selected from a large database of patients with FM referring to the Rheumatology Department of the Polytechnic University of Marche in Jesi (Ancona, Italy), the Internal Medicine and Rheumatology Unit of Parma Hospital, and the Rheumatology Unit of “L. Sacco” University Hospital in Milan (Italy). The following subjects have been excluded from the study: those affected by cardiovascular disease, moderate-to-severe chronic lung disease, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled thyroid disturbances, inflammatory rheumatic conditions (ie, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue diseases), and/or psychoses or active suicidal ideation. A total of 496 patients have been screened, of which 143 refused to participate. The remaining 353 patients satisfied the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for FM.Citation27 All patients have provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the hospital Ethics Committee (Comitato Unico Regionale - ASUR Marche).

Internet-based PROs

The patients logged into the website (http://www.fibromialgiaitalia.it) developed for the present study. During the first login to the website, each patient was asked to provide consent and to complete the questionnaires. The questions were displayed using radio buttons. Each question had to be completed before the software continued to the following page. During the first visit, each patient has received a secure username/password combination in order to have access to the website and a brief training on the use of FIQRCitation19 and the self-administered Fibromyalgia Activity Score (FAS)Citation28 questionnaires. The FIQR was developed by Burckhardt et alCitation29 in an attempt to address the limitations of the original FIQ.Citation29 The Italian version of FIQCitation20 is composed of 21 items that are rated using an 11-point numerical scale (0–10, with 10 being the worst) and cover three domains: physical function, overall impact, and symptoms over the previous 7 days. The total score for the 9-item “function domain” (range: 0–90) is divided by three, the total score for the 2-item “overall impact domain” (range: 0–20) is divided by one, and the total score for the 10-item “symptom domain” (range: 0–100) is divided by two. The global score is given by the sum of the scores of the three domains (range: 0–100). FM is classified as mild (from 0 to 38), moderate (from 39 to 58), or severe (from 59 to 100).Citation30 The FAS is a valid, reliable, and responsive disease-specific composite measure for patients with FM.Citation30 The FAS index combines scores related to fatigue (range: 0–10) and the quality of sleep (range: 0–10) and scores obtained by the Self-Administered Pain Scale (SAPS) in order to provide a single measure of disease activity (range: 0–10). The SAPS asks patients to classify pain in 16 non-articular sites (0 =none, 1 =mild, 2 =moderate, 3 =severe), and the final total score of 0–48 is transformed into a scale of 0–10. At the end of the study, the electronically collected raw data were extracted as anonymous. The database was completed by the demographic characteristics of the patients.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of the continuous variables are given as mean values ± standard deviation and median values with their 25th to 75th percentiles, and those of the categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. The number of clusters was chosen by examining the dendrogram and considering clinical interpretability and usefulness. The variables of interest in the clusters were subsequently compared using analysis of variance followed by between-cluster pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment to a significance level of 0.05. Analysis of variance was also used to compare the behavior of the measured clinical subscales of the FIQR in the defined FM subgroups. The level of significance for all of the tests was 5%. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Windows release 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and MedCalc, version 12.7.0 (Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Demographic characteristics

shows the demographic characteristics of the 353 responders (85.3% women). Mean age of responders was 50.9 years, 60.8% were married and only 24.1% had a high school/university education. The mean duration of pain was 4.7 years (range: 1–18 years). Patients were moderately overweight as their mean body mass index was 28.5 (body mass index of >25 and >30 were found in 40% and 7% of cases, respectively). No significant differences of demographic characteristics were observed between patients who agreed to participate in the study and those who did not.

Table 1 Participant demographics (n=353)

Descriptive statistics

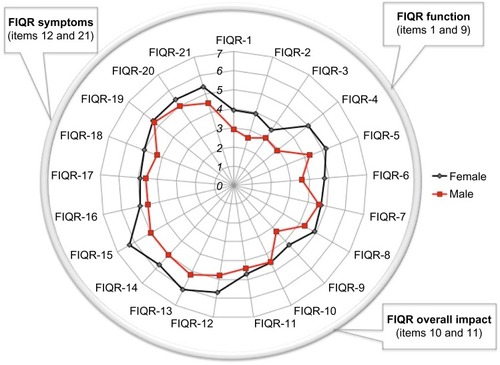

shows FIQR item, subscale, and total scores. The highest scoring items (those with the greatest disease impact) were the following symptoms related: sleep quality (FIQR15), fatigue/energy (FIQR13), pain (FIQR12), stiffness (FIQR14), tenderness (FIQR19), balance problems (FIQR20), and environmental sensitivity (FIQR21). The lowest scored items included functional activities such as brushing/combing hair (FIQR1), preparing a home-made meal (FIQR3), walking continuously for 20 minutes (FIQR2), shopping for groceries (FIQR9), and changing bed sheets (FIQR7).

Table 2 Scores obtained on the FIQR (mean and median values, SDs and 95% confidence intervals for each item, subdimensions and total score of the FIQR, and for total score of the FAS) by the study patients (n=353)

shows the distribution of the FIQR scores. The impact of the disease on functional domains such as personal care (FIQR1) and activities of daily living (FIQR3, FIQR4, FIQR5, FIQR7, and FIQR9) was greater among women, but the differences were not significant. Similarly, pain (FIQR12), fatigue (FIQR13), rigidity (FIQR14), and sleep quality (FIQR15) were not significantly associated with sex.

Figure 1 Spydergrams of the FIQR domains.

Abbreviation: FIQR, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised version.

SAPS was used to assess the presence of pain in 16 body sites. A high proportion of patients reported pain in the neck (81.4%), upper back (70.1%), and lower back (83.2%) (). There was no difference between sexes in relation to any of the sites.

Cluster analysis

It was used hierarchical agglomerative clustering of the 21 subscales of the FIQR, respectively, accounting for 33.1%, 34%, and 32.9% of the sample. The three-cluster solution distinguished three broad levels of severity. Clusters 1 and 3 correspond to the lowest and highest average scores, respectively, and cluster 2 to lower levels of depression, anxiety, and less severe memory problems compared to the other scales of the FIQR ( and ). The pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between each cluster for all but a few symptoms. Clusters 2 and 3 were not significantly different in terms of walking continuously for 20 minutes (P=0.11) or lifting and carrying a bag full of groceries (P=0.21) ().

Figure 3 Cluster profiles.

Abbreviation: FIQR, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised version.

Table 3 Subgrouping of fibromyalgia samples based on scores obtained on the FIQR (mean and standard deviations) for each item, subdimensions and total score

Discussion

Over the last few years, the ongoing evolution of computer software and technology has greatly improved the ability to collect PROs data. One major advantage of computerized questionnaires is to collect good-quality data without any missing or problematic responses commonly found by using paper questionnaires.Citation21–Citation25,Citation31 Online surveys enable respondents to answer questionnaires according to their preferences (eg, ways and connection times) while connected to the Internet browser.Citation22–Citation24

Our questionnaire was completed by 353 patients with FM, and demographic features of respondents were similar to previous epidemiologic studies and surveys.Citation17,Citation28,Citation32–Citation34 Respondents have reported several symptoms mainly including poor quality sleeping, fatigue/lack of energy, pain, stiffness, tenderness, and increasing environmental sensitivity. There were no significant differences between sexes in these domains. The tendency for women to have higher scores in some domains (eg, brushing/combing hair, preparing home-made meals, vacuum cleaning, scrubbing/sweeping floors, or shopping) seems related to the fact that those daily activities are peculiar to female sex.

Cluster analysis has revealed three distinctive subgroups of symptoms: cluster 1 lowest mean total FIQR and FIQR scores (ranging from 0 to ≤39);Citation35 cluster 2 moderate symptoms and mild levels of cognitive/psychological impairment (scores ranging from 39 to ≤59); and cluster 3 severe symptoms (scores ranging from 59 to 100). Our findings have some similarities with results from previous cluster analyses in patients with FM. Vincent et alCitation15 found that a four-cluster solution best fit their results: clusters 1 and 4 correspond to the lowest and highest scores among all symptoms and clusters 2 and 3 intermediate levels of anxiety and depression, with cluster 2 having lower levels of depression and anxiety than cluster 3, despite higher levels of pain. Similarly, the cluster analysis of Wilson et alCitation36 identified four clusters: cluster 1 had high scores in all three domains, cluster 2 had moderate scores in the two physical symptoms domains and high cognitive/psychological symptom scores, cluster 3 had moderate scores in the two physical symptoms domains and low cognitive/psychological symptoms scores, and cluster 4 had low scores in all symptoms domains. Clusters 2 and 3 were therefore distinguished by differences in the severity of depression and anxiety, which is also consistent with the findings of Giesecke et al.Citation8 In this study, the authors have identified three patient-subsets mainly on the basis of differences in pain and psycho pathology as follows: first one characterized by moderate levels of mood, catastrophizing and perceived pain control, and low levels of tenderness; second one characterized by high degree of mental impairment, highest catastrophizing subscales and severe pain; third one characterized by normal mood ratings, very low levels of catastrophizing and the highest level of perceived pain control even though they showed extreme tenderness when evoked pain was tested. However, our findings are not directly comparable with those of these studiesCitation8,Citation15,Citation36 because they used measurements of experimental pain and some variables were not included in our study.

De Souza et alCitation13 also highlighted anxiety and depression as differentiating factors in their two-cluster model based on the FIQ: both FM subgroups showed hyperalgesic responses to experimental pain, but type I was characterized by the lowest levels of anxiety, depression, and morning tiredness and type II by high levels of pain, fatigue, morning tiredness, stiffness, anxiety, and depression. Similarly, Docampo et alCitation37 have identified three subgroups in a series of 1,446 Spanish patients. One with low symptom scores and few comorbidities; second one with high symptom scores and multiple comorbidities; and third one with high symptom scores but few comorbidities. Psychological and cognitive impairments (such as memory deficits) are associated with a wide variety of pain conditions.Citation38–Citation40 The fact that these clinical features seem to be more severe in patients with FM suggested that a group of alterations in a disorder may enhance the magnitude of specific symptoms such as pain. Williams et alCitation41 found that the domains of mood and fatigue were closely associated with perceived dyscognitions in FM, whereas pain was uniquely associated with perceived language deficits and, unexpectedly, was not related to attention or concentration. In line with this, our findings indicate that memory problems and psychological symptoms (anxiety and depression) were not associated with pain intensity in cluster 2.

Our study has some methodological limitations. First of all, the use of the Internet browser was associated with various socioeconomic and demographic factors, including age, sex, location, and education, and users could not to be representative of target population. However, Internet-based assessments have been accepted by a sizeable percentage (71.2%) of the eligible patients. Second, we did not select patients on the basis of their ongoing pharmacological therapy, although this is an important factor that may mediate dyscognition in FM. It is extremely rare to find a diagnosed subject who is not taking continuous doses of antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, duloxetine), antiepileptic drugs (gabapentin, pregabalin), or strong analgesics (tramadol, opioids),Citation42,Citation43 and it is entirely reasonable to expect that medications may reduce cognitive test performances,Citation44 thus making difficult to distinguish which deficits may be attributable to FM and which to drugs. A final limitation is that the analysis was based on a population of adults from a relatively limited geographical area in central and northern Italy.

Conclusion

We have identified three subgroups of FM samples in a large cohort of FM using an Internet survey. Cluster 1 had the lowest mean total FIQR score, which also fell within the mild symptom severity range of the FIQR, whereas cluster 3 was characterized by severe symptoms, cluster 2 captured moderate symptoms with mild levels of cognitive/psychological symptoms. Web surveys allow rapid updating of questionnaire content and question ordering according to user responses and could provide rationale to support the study of individualized clinical evaluation and may be used to identify optimal treatment strategies.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. FS was the principal investigator, was responsible for the everyday coordination and management of the study, created and managed the data collection web platform, analyzed the data, and contributed to writing the manuscript. FM and PSP participated in conceiving the study, provided clinical support, and were involved in the study design. AD, MDC, AC, and FA provided clinical support and contributed to writing the manuscript. AD, AC, and RC participated in data acquisition of data and were involved in revising the intellectual content of the paper. All of the authors have read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all patients who kindly completed the questionnaires on the Website. Furthermore, we wish to thank Advice Pharma Group (www.advicepharma.com) and Appycom S.r.l. (http://www.appycom.it/site) for the creation of the web-portal and the technical assistance provided during the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MeasePFibromyalgia syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatmentJ Rheumatol Suppl200532SupplS6S21

- SalaffiFDe AngelisRGrassiWMArche Pain Prevalence, INvestigation Group (MAPPING) studyPrevalence of musculoskeletal conditions in an Italian population sample: results of a regional community-based study. I. The MAPPING studyClin Exp Rheumatol200523681982816396700

- WolfeFBrählerEHinzAHäuserWFybromyalgia prevalence, somatic symptom reporting, and the dimensionality of polysymptomatic distress: results from a survey of the general populationArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201365577778523424058

- MeasePJArnoldLMCroffordLJIdentifying the clinical domains of fibromyalgia: contributions from clinician and patient Delphi exercisesArthritis Rheum200859795296018576290

- AmbroseKRGracelyRHGlassJMFibromyalgia dyscognition: concepts and issuesReumatismo201264420621523024965

- BennettRMRussellJCappelleriJCBushmakinAGZlatevaGSadoskyAIdentification of symptom and functional domains that fibromyalgia patients would like to see improved: a cluster analysisBMC Musculoskelet Disord20101113420584327

- HurtigIMRaakRIKendallSAGerdleBWahrenLKQuantitative sensory testing in fibromyalgia patients and in healthy subjects: identification of subgroupsClin J Pain201117431632211783811

- GieseckeTWilliamsDAHarrisRESubgrouping of fibromyalgia patients on the basis of pressure-pain thresholds and psychological factorsArthritis Rheum200348102916292214558098

- HamiltonNAKarolyPZautraAJHealth goal cognition and adjustment in women with fibromyalgiaJ Behav Med200528545546616179980

- BorgCPadovanCThomas-AntérionCPain-related mood influences pain perception differently in fibromyalgia and multiple sclerosisJ Pain Res20147818724489475

- ThiemeKTurkDCHeterogeneity of psychophysiological stress responses in fibromyalgia syndrome patientsArthritis Res Ther200681R916356200

- MalinKLittlejohnGOPsychological control is a key modulator of fibro-myalgia symptoms and comorbiditiesJ Pain Res2012546347123152697

- de SouzaJBGoffauxPJulienNPotvinSCharestJMarchandSFibromyalgia subgroups: profiling distinct subgroups using the Fibro-myalgia Impact Questionnaire. A preliminary studyRheumatol Int200829550951518820930

- HäuserWAkritidouIFeldeESteps towards a symptom-based diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome. Symptom profiles of patients from different clinical settingsZ Rheumatol200867651151518830659

- VincentAHoskinTLWhippleMOOMERACT-based fibro-myalgia symptom subgroups: an exploratory cluster analysisArthritis Res Ther201416546325318839

- AldenderferMSBlashfieldRKCluster AnalysisNewbury Park, CASage Publications, Inc1984

- SalaffiFSarzi-PuttiniPGirolimettiRAtzeniFGaspariniSGrassiWHealth-related quality of life in fibromyalgia patients: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population using the SF-36 health surveyClin Exp Rheumatol200927Suppl 56S67S7420074443

- ChoyEHArnoldLMClauwDJContent and criterion validity of the preliminary core dataset for clinical trials in fibromyalgia syndromeJ Rheumatol200936102330233419820222

- BennettRMFriendRJonesKDWardRHanBKRossRLThe Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric propertiesArthritis Res Ther2009114R12019664287

- SalaffiFFranchignoniFGiordanoACiapettiASarzi-PuttiniPOttonelloMPsychometric characteristics of the Italian version of the revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire using classical test theory and Rasch analysisClin Exp Rheumatol201331Suppl 79S41S4923806265

- DellifraineJLDanskyKHHome-based telehealth: a review and meta-analysisJ Telemed Telecare2008142626618348749

- MeystreSThe current state of telemonitoring: a comment on the literatureTelemed J E Health2005111636915785222

- ParéGJaanaMSicotteCSystematic review of home telemonitoring for chronic diseases: the evidence baseJ Am Med Inform Assoc200714326927717329725

- RoineROhinmaaAHaileyDAssessing telemedicine: a systematic review of the literatureCMAJ2001165676577111584564

- DemirisGAfrinLBSpeedieSPatient-centered applications: use of information technology to promote disease management and wellness. A white paper by the AMIA knowledge in motion working groupJ Am Med Inform Assoc200815181317947617

- WilliamsDAKuperDSegarMMohanNShethMClauwDJInternet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trialPain2010151369470220855168

- WolfeFClauwDJFitzcharlesMAThe American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severityArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062560061020461783

- SalaffiFSarzi-PuttiniPGirolimettiRGaspariniSAtzeniFGrassiWDevelopment and validation of the self-administered fibromyalgia assessment status: a disease-specific composite measure for evaluating treatment effectArthritis Res Ther2009114R12519686606

- BurckhardtCSClarkSRBennettRMThe Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: development and validationJ Rheumatol19911857287331865419

- BennettRMBushmakinAGCappelleriJCZlatevaGSadoskyABMinimal clinically important difference in the fibromyalgia impact questionnaireJ Rheumatol20093661304131119369473

- StreinerDLNormanGRMethods of administrationHealth Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use2nd edNew YorkOxford Medical1995189205

- BennettRMJonesJTurkDCRussellIJMatallanaLAn internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgiaBMC Musculoskelet Disord200782717349056

- ChandranASchaeferCRyanKBaikRMcNettMZlatevaGThe comparative economic burden of mild, moderate, and severe fibromyalgia: results from a retrospective chart review and cross-sectional survey of working-age U.S. adultsJ Manag Care Pharm201218641542622839682

- PerrotSSchaeferCKnightTHufstaderMChandranABZlatevaGSocietal and individual burden of illness among fibromyalgia patients in France: association between disease severity and OMERACT core domainsBMC Musculoskelet Disord2012132222340435

- SchaeferCChandranAHufstaderMThe comparative burden of mild, moderate and severe fibromyalgia: results from a cross-sectional survey in the United StatesHealth Qual Life Outcomes201197121859448

- WilsonHDRobinsonJPTurkDCToward the identification of symptom patterns in people with fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum200961452753419333980

- DocampoEColladoAEscaramìsGCluster analysis of clinical data identifies fibromyalgia subgroupsPLoS One201389e7487324098674

- KunerRCentral mechanisms of pathological painNat Med201016111258126620948531

- SlobodinGReyhanIAvshovichNRecently diagnosed axial spondyloarthritis: gender differences and factors related to delay in diagnosisClin Rheumatol20113081075108021360100

- MoriartyOMcGuireBEFinnDPThe effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical researchProg Neurobiol201193338540421216272

- WilliamsDAClauwDJGlassJMPerceived cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndromeJ Musculoskelet Pain20111926675

- SommerCHauserWAltenRDrug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guidelineSchmerz201226329731022760463

- PengXRobinsonRLMeasePLong-term evaluation of opioid treatment in fibromyalgiaClin J Pain201531171324480913

- MiróELupiáñezJHitaEMartínezMPSánchezAIBuela-CasalGAttentional deficits in fibromyalgia and its relationships with pain, emotional distress and sleep dysfunction complaintsPsychol Health201126676578021391131