Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the health and economic burden associated with fibromyalgia among adults in Japan.

Materials and methods

Data from the 2011–2014 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (n=115,271), a nationally representative survey of adults, were analyzed. The greedy matching algorithm was used to match the respondents who self-reported a diagnosis of fibromyalgia with those not having fibromyalgia (n=256). Generalized linear models, controlling for covariates (eg, age and sex), examined whether the respondents with fibromyalgia differed from matched controls based on health status (health utilities; Mental and Physical Component Summary scores from Medical Outcomes Study: 12-item Version 2 and 36-item Version 2 Short Form Survey), sleep quality (ie, sleep difficulty symptoms), work productivity (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire – General Health Version 2.0), health care resource use, and estimated annual indirect and direct costs (based on published annual wages and resource use events) in Japanese yen (¥).

Results

After adjustment for covariates, respondents with fibromyalgia relative to matched controls scored significantly lower on health utilities (adjusted means =0.547 vs 0.732), Mental Component Summary score (33.15 vs 45.88), and Physical Component Summary score (39.22 vs 50.81), all with P<0.001; these differences exceeded the clinically meaningful levels. In addition, those with fibromyalgia reported significantly poorer sleep quality than those without fibromyalgia. Respondents with fibromyalgia compared with those without fibromyalgia experienced significantly more loss in work productivity and health care resource use, resulting in those with fibromyalgia incurring indirect costs that were more than twice as high (adjusted means =¥2,826,395 vs ¥1,201,547) and direct costs that were nearly six times as high (¥1,941,118 vs ¥335,140), both with P<0.001.

Conclusion

Japanese adults with fibromyalgia experienced significantly poorer health-related quality of life and greater loss in work productivity and health care use than those without fibromyalgia, resulting in significantly higher costs. Improving the rates of diagnosis and treatment for this chronic pain condition may be helpful in addressing this considerable humanistic and economic burden.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a rheumatic condition characterized by chronic pain, fatigue, and other physical and/or psychological symptoms.Citation1 It is commonly associated with a variety of comorbidities, including, but not limited to, migraines and sleep difficulties,Citation2,Citation3 and also with mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression.Citation4 Recently, in Japan, the prevalence of fibromyalgia was estimated to be 2.1% among adults (aged ≥20 years), with the majority (60.5%) of them being female.Citation5

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines indicate that diagnosis of fibromyalgia is warranted based on patients’ scores on the Widespread Pain Index (≥7) and Symptom Severity Scale (≥5; or Widespread Pain Index score of 3–6 coupled with Symptom Severity Scale score ≥9), symptoms that have consistently recurred for at least 3 months, and no condition otherwise present that would account for the pain experienced by the patient.Citation1 The diagnostic criteria in the ACR guidelines have been validated for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia patients in Japan.Citation6

Although the epidemiology of fibromyalgia has been well examined in Japan, most of the research on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or economic burden has been conducted in Western countries. Among Portuguese women, fibromyalgia was negatively associated with all dimensions of HRQoL, and the largest decreases were observed for physical functioning, physical role functioning, and general health.Citation7 US adults (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with fibromyalgia reported poorer sleep quality and health status, as well as more severe pain, than those with or without chronic pain.Citation8 Another study on US adults (aged 18–65 years) demonstrated that severity has an impact on degree of burden; those with severe fibromyalgia self-reported greater pain intensity and fatigue, with poorer sleep quality, HRQoL, and mental health (anxiety and depression), than those with either moderate or mild fibromyalgia.Citation9 Moreover, several studies reveal that the health burden of fibromyalgia is greater than that of other similar chronic conditions. A Turkish study found that patients with fibromyalgia reported lower HRQoL than those with rheumatoid arthritis.Citation10 A Japanese study found that individuals with fibromyalgia experienced greater symptom severity and number of symptoms than patients with chronic pain.Citation5

Compared to controls, US adults with fibromyalgia had higher health care resource use over the course of 1 year, including hospitalizations, visits to medical specialists, and total number of medical visits.Citation11 Furthermore, US patients with fibromyalgia (vs those with or without chronic pain) had greater health care resource use, including medications, supplements, health care provider visits, emergency room (ER) visits, and physical treatments.Citation10 Collectively, these findings suggest that direct costs for health care resource use are likely to be substantially higher among adults with fibromyalgia. Moreover, other studies have shown that even greater direct costs can be incurred when the severity of fibromyalgia symptoms increases.Citation12

In addition, fibromyalgia has a negative impact on work productivity; more than half (55.8%) of working-age (<65 years old) US adults with fibromyalgia reported being unable to work because of their health (vs only 5.8% of those without fibromyalgia).Citation11 These effects on work productivity can differ by severity, which has implications for indirect costs. For example, more than half (60%) of US adults with severe fibromyalgia reported work disruptions, due to their condition, compared to 45% and 15% of those with moderate or mild fibromyalgia, respectively.Citation10 Similarly, those with severe fibromyalgia missed an average of 3 days of work per month (39 days annually), whereas adults with moderate (1 day per month, 13 days annually) or mild (0.4 days per month, 5 days annually) fibromyalgia missed substantially less work. US adults with severe fibromyalgia had significantly greater 3-month direct ($2,329) and indirect ($8,285) costs than those with either moderate ($1,415 direct and $5,139 indirect) or mild ($1,213 direct and $1,341 indirect) fibromyalgia.Citation12 However, regardless of severity of fibromyalgia, indirect costs accounted for the majority of these patients’ total costs.

Only a few research studies investigating the health and economic burden of fibromyalgia are available in Japan. The available research studies on the burden of fibromyalgia are incomplete, as more studies, to date, have been conducted in the US or EU. Therefore, it is unclear whether findings can be generalized to Japanese adults with fibromyalgia. The few studies using data from Japan include only a limited number of outcomes (eg, symptom severity, but not HRQoL or costs), or they are not fibromyalgia-specific (eg, all chronic pain conditions examined in the aggregate). Hence, to overcome the limitations in the existing literature, the present study sought to explore differences between Japanese adults with fibromyalgia and those without fibromyalgia on health status, sleep difficulties, work productivity and activity impairment, health care resource use, and associated costs. Results from this study can help to clarify better the health and economic burdens of fibromyalgia among Japanese adults.

Materials and methods

Data source

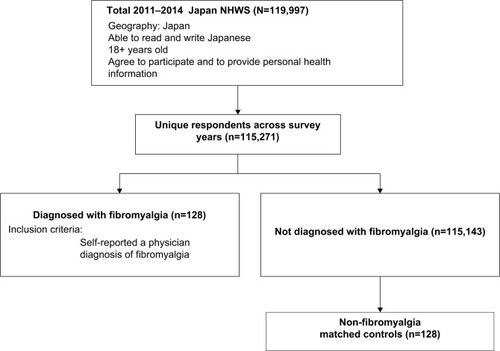

Data from the 2011–2014 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) were analyzed in this study. The data for all 4 years were combined to maximize the sample size. As respondents could participate in multiple survey years, most recent data of respondents were retained for analyses. In particular, all unique respondents from the 2011–2014 Japan NHWS (n=115,271) were initially included in the analyses ().

The recruitment of panel members in the Japan NHWS strived to approximate the distribution of adults in the Japanese population. More details on the Japan NHWS participant recruitment procedures and sampling framework have been reported in another study.Citation13 The survey was approved by Essex Institutional Review Board, Inc. (Lebanon, NJ, USA), and informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to participation in the present study.

Measures

Fibromyalgia

Respondents who self-reported a diagnosis of fibromyalgia from a health care provider were considered to have fibromyalgia, and all other respondents were considered not to have fibromyalgia (ie, control respondents). A propensity score matching approach was used to match fibromyalgia respondents with control respondents, based on demographics and health characteristics.

Demographics

Demographic variables included year of survey participation (2011, 2012, 2013, or 2014), sex (male or female), age, education (university degree vs all others), household income (¥) (<¥3 MM, ¥3 MM to <¥5 MM, ¥5 MM to <¥8 MM, ≥¥8 MM, or decline to answer), and health insurance (national health insurance, social insurance, late-stage elderly insurance, others, or no insurance).

Health history

Health history included smoking status (current smoker, former smoker, or never smoker), exercise behavior (whether exercised for 20 minutes in ≥1 day/month or did not exercise in the past month), alcohol consumption (consumes or abstains from alcohol), body mass index category (based on the recommendations of the World Health OrganizationCitation14 for Asian populations: underweight [<18.5kg/m2], acceptable risk [18.5 to <23kg/m2], increased risk [23 to <27.5kg/m2], high risk [≥27.5kg/m2], or decline to provide weight), and the Charlson comorbidity index, a measure assessing comorbidity mortality.Citation15

HRQoL

HRQoL was defined by the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument version 2 (SF-36v2Citation16; used in the survey years 2012–2014) or the 12-item Short-Form Survey Instrument version 2 (SF-12v2Citation17; used in the survey year 2011). Eight health domains (ie, physical functioning, physical role limitations, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role limitations, and mental health) and two summary scores (Physical Component Summary [PCS] and Mental Component Summary [MCS]) were calculated from the SF-36v2 or SF-12v2; higher scores indicate better health.Citation16 A health state utility score is calculated from SF-36v2 or SF-12v2 by using the SF-6D algorithm. The SF-6D-derived health utility index is scored from 0 to 1, where 1 represents perfect health.Citation18 Minimally important differences (MIDs), suggested by some previous studies, are 5 points for the norm-based health domain scores, 3 points for the norm-based component summary scores, and 0.041 points for SF-6D health utilities.Citation17,Citation19

Sleep difficulties

All NHWS respondents were asked the following question, “Thinking of the sleeplessness or difficulty sleeping that you experience, which of the following sleep problems or symptoms do you regularly experience?” Then, the respondents selected from a dropdown list of the symptoms that were applicable to each of them. In this study, sleep difficulties were operationalized as the presence (or absence) of “difficulty falling asleep,” “waking during the night and not being able to get back to sleep,” “waking up several times during the night,” and “poor quality of sleep”; these items most closely reflect the insomnia domains of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition,Citation20 namely sleep onset symptoms, sleep maintenance symptoms, and restorative sleep. Each sleep difficulty symptom was examined individually and had a binary response option (presence or absence).

Work productivity and activity impairment

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – General Health Questionnaire Version 2 generates four subscales assessing work productivity and activity impairment.Citation21 Absenteeism represents the percentage of time missed from work, presenteeism represents the percentage of time impaired while at work, overall work impairment is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism, and activity impairment represents the percentage of impairment in daily activities. The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – General Health Questionnaire subscales are scored in the form of percentages; higher values indicate greater impairment as a result of the patient’s health in the past 7 days. Absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were only calculated for respondents who were currently employed (full-time, part-time, or self-employed), whereas activity impairment was calculated for all respondents.

Health care resource use

Health care resource use was measured by the number of health care provider visits, the number of ER visits, and the number of times hospitalized in the past 6 months for one’s own health condition (all-cause).

Costs

The methodology for costs was adopted from the study by Sadosky et alCitation13 on lower back pain using Japan NHWS 2013, and more details can be found from this study (refer page 121–122). Briefly, the Lofland methodCitation22,Citation23 was used to calculate annual indirect costs, which involved multiplying overall work impairment by estimated hourly wage rates from the Japan Basic Survey on Wage Structure 2011. As physician visits and hospitalizations for the past 6 months were asked about in the NHWS, annual direct costs were estimated by multiplying the number of physician visits and hospitalizations by two. Then, these costs were multiplied by the corresponding unit cost for physician visits and hospitalizations obtained from Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Japan. ER visits are associated with trivial independent costs in Japan and, thus, were not included in the direct cost calculation.Citation24 The NHWS respondents provided the number of hospitalizations in the past 6 months; however, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare reports only a cost per day for hospitalizations. Thus, to equate these measures, cost per day was multiplied by the average number of days per hospitalization (18.5 days as reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development).Citation25 All cost figures were calculated in Japanese yen (¥).

Statistical analyses

Identifying a matched control group

In order to minimize the sample size imbalance between respondents with and without fibromyalgia, a propensity score-matching process was used to identify a group without fibromyalgia that closely resembled those with fibromyalgia.Citation26 To do so, respondents with and without fibromyalgia were compared on the basis of demographics and health history variables by using c2 test (for categorical variables) and independent samples t-test (for continuous variables). As the number of potential predictors would exceed what could be statistically supported with the present sample size, a covariate selection process was used on the basis of both theoretical and statistical grounds.Citation27 Variables that differed between groups at a P-value of <0.25 were used in a logistic regression model to predict fibromyalgia presence (ie, fibromyalgia vs no fibromyalgia).

The P<0.25 cutoff was set in order to ensure that relevant variables were included even if suppression was present.Citation28 Suppression is present when the strength of the relationship between two variables is increased due to the adjustment of a third variable. Therefore, if suppression is present, a variable that has a nonsignificant correlation with fibromyalgia presence in an unadjusted analysis (eg, P=0.10) may, in fact, be a significant predictor of the presence of fibromyalgia by multivariable regression.

By selecting a P<0.25 cutoff, exclusion of meaningful variables can be avoided. Propensity score values from this model were saved and subsequently used to match each respondent with fibromyalgia to a respondent without fibromyalgia whose propensity score value was identical. In particular, a greedy matching algorithm was used, which identified controls to match to a single case at up to eight decimal places of the propensity score (and as little as one decimal place, if no other suitable control was identified).Citation29 Matched respondents were considered a matched control group without fibromyalgia, and the respondents who were not matched were excluded from further analyses.

Postmatch considerations

Postmatch, respondents with fibromyalgia and matched controls were compared with respect to demographics and health history variables by using χ2 test and independent samples t-test. These analyses tested the degree of balance between groups and determined whether any variables should further be controlled. Following recommendations by Austin,Citation30 variables that had a standardized mean difference of ≥0.10 between groups postmatch were considered as covariates in subsequent multivariable analyses. In particular, if any demographic or health history variable differed between groups postmatch, then a series of generalized linear models was conducted to predict each outcome, specifying the appropriate distribution (eg, binomial for sleep difficulties, due to binary responses on sleep items, normal for health status variables, and negative binomial for all count outcomes [Work Productivity and Activity Impairment metrics, health care resource use, and costs]). These models had fibromyalgia status (yes vs no) as the primary independent variable, with any variable that significantly differed between fibromyalgia status groups included as covariates. Adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported from these models. Any two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Sample demographics and matching results

Of those who reported fibromyalgia (n=128), the average age was 42.62 years, and 59.4% were female. The majority had less than a university degree (59.4%), national health insurance (53.1%), body mass index categories of acceptable risk (39.8%) or increased risk (25.8%), consumed alcohol (63.3%), and did not exercise (56.2%; ). In terms of disease characteristics, the mean number of years experiencing fibromyalgia was 6.15 (standard deviation =6.68), and most respondents reported either mild (32.0%) or moderate (43.0%) levels of pain severity (). In addition, the most commonly used Rx for fibromyalgia was pregabalin (31.3%), duloxetine hydrochloride (10.9%), and loxoprofen (10.9%; ).

Table 1 Demographics and health characteristics between diagnosed fibromyalgia and nonfibromyalgia matched controls

Table 2 Disease characteristics and current treatment among those diagnosed with fibromyalgia

Postmatch, several demographics and health characteristics between the fibromyalgia and nonfibromyalgia groups had standardized mean differences >0.10, thus representing an imbalance between groups (). Therefore, age, sex, income, insurance, body mass index, and exercise were used as covariates in multivariable analyses comparing outcomes between the fibromyalgia and nonfibromyalgia groups. Comorbidity burden (Charlson comorbidity index), survey year, education, smoking behavior, and alcohol consumption had standardized mean differences <0.10, indicating that these characteristics were similar between groups as a result of matching.

HRQoL burden

Unadjusted comparisons

Unadjusted two-sample comparisons revealed that those with fibromyalgia, relative to those without fibromyalgia, had substantially lower HRQoL, including lower SF-6D health utilities, MCS, PCS, and all of the health domain scores (eg, bodily pain, role physical, and vitality scale; ). In addition, incidences of sleep difficulties among those with fibromyalgia were also much higher than among those without fibromyalgia, including “difficulty falling asleep,” “waking during the night and not being able to get back to sleep,” “waking up several times during the night,” and “poor sleep quality” ().

Table 3 Unadjusted health and economic outcomes between those diagnosed with fibromyalgia and nonfibromyalgia matched controls

Adjusted comparisons

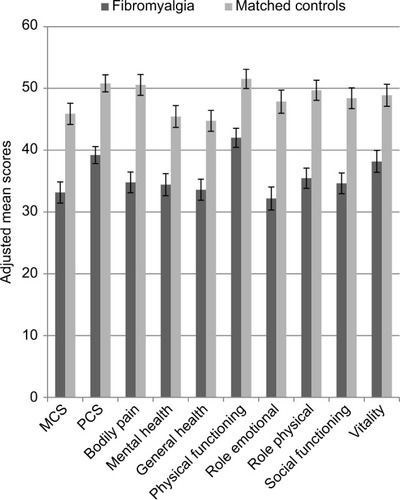

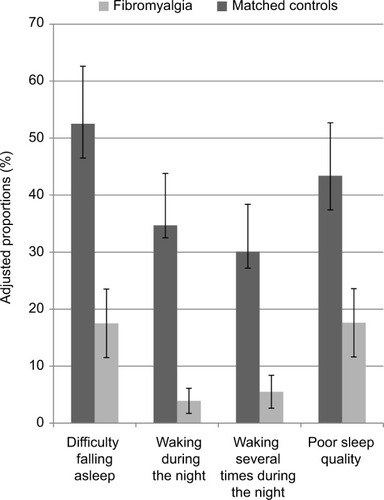

After adjusting for covariates, results were consistent with unadjusted two-sample comparisons between those with fibromyalgia and those without fibromyalgia. Those with fibromyalgia scored 12.72 points lower on MCS (adjusted means =33.15 [CI =31.45%–34.86%] vs 45.88 [CI =44.17%–47.59%]), 11.59 points lower on PCS (adjusted means =39.22 [CI =37.84%–40.60%] vs 50.81 [CI =49.43%–52.19%]), and 0.185 points lower on health utilities (adjusted means =0.547 [CI =0.528%–0.566%] vs 0.732 [CI =0.713%–0.751%]), relative to those without fibromyalgia (all P<0.001). In addition, all of the health domain scores were nearly 10–16 points lower for those with fibromyalgia (). Respondents with fibromyalgia also experienced significantly greater incidences of all sleep difficulties assessed (). Notably, compared to those without fibromyalgia, those with fibromyalgia experienced nearly 13 times the odds of “waking during the night and not being able to get back to sleep” (adjusted proportions =34.7% [CI =25.6%–45.0%] vs 3.9% [CI =1.7%–8.8%]) and seven times the odds of “waking up several times during the night” (adjusted proportions =30.1% [CI =21.8%–40.0%] vs 5.5% [CI =2.6%–11.1%]), all with P<0.001.

Figure 2 Adjusted means of SF-36v2/SF-12v2 component summary and domain scores by diagnosed fibromyalgia versus nonfibromyalgia matched controls.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36v2, 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument version 2; SF-12v2, 12-Item Short Form Survey Instrument version 2.

Figure 3 Adjusted proportions for sleep difficulties (% experienced) by those diagnosed with fibromyalgia versus nonfibromyalgia matched controls.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Economic burden

Unadjusted comparisons

Unadjusted two-sample comparisons showed greater economic burden among fibromyalgia respondents, compared to those without fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia respondents had nearly seven times as much absenteeism and approximately twice as much presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment (). Furthermore, health care resource use was much higher among respondents with fibromyalgia, with approximately twice as many health care provider visits, eleven times as many ER visits, and five times as many hospitalizations than among respondents without fibromyalgia (). Consequently, indirect costs were approximately twice as high and direct costs were more than four times as high among respondents with fibromyalgia ().

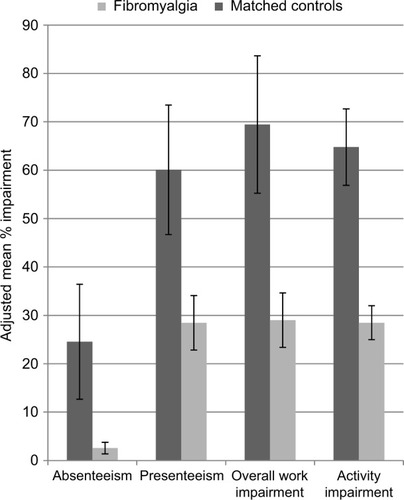

Adjusted comparisons

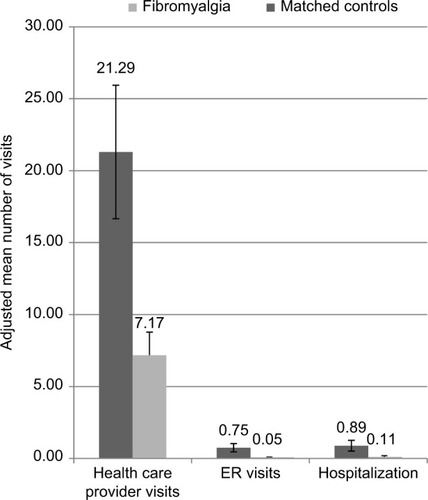

Results from adjusted comparisons were consistent with unadjusted comparisons showing substantially greater economic burden among those with fibromyalgia, compared to those without fibromyalgia. Those with fibromyalgia experienced nearly ten times as much absenteeism (adjusted means =24.54% [CI =12.68%–47.49%] vs 2.57% [CI =1.37%–4.81%]), twice as much presenteeism (adjusted means =60.08% [CI =46.69%–77.30%] vs 28.45% [CI =22.82%–35.47%]), and twice as much overall work impairment (adjusted means =69.43% [CI =55.22%–87.30%] vs 29.02% [CI =23.39%–36.01%]), all with P<0.001. Activity impairment was also twice as high among those with fibromyalgia compared to those without fibromyalgia (adjusted means =64.76% [CI =56.88%–73.75%] vs 28.48% [CI =24.98%–32.46%]; P<0.001; ). For health care resource use, respondents with fibromyalgia had nearly three times as many health care provider visits (adjusted means =21.29 [CI =16.66%–27.23%] vs 7.17 [CI =5.56%–9.25%]), nearly 14 times as many ER visits (adjusted means =0.75 [CI =0.46%–1.21%] vs 0.05 [CI =0.02%–0.13%]) and nearly eight times as many hospitalizations (adjusted means =0.89 [CI =0.51%–1.54%] vs 0.11 [CI =0.05%–0.24%]), all with P<0.001 ().

Figure 4 Adjusted means for absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment (% impairment) by those diagnosed with fibromyalgia versus nonfibromyalgia matched controls.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Figure 5 Adjusted mean number of health care provider visits, ER visits, and hospitalizations in the past 6 months by those diagnosed with fibromyalgia versus nonfibromyalgia matched controls.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ER, emergency room.

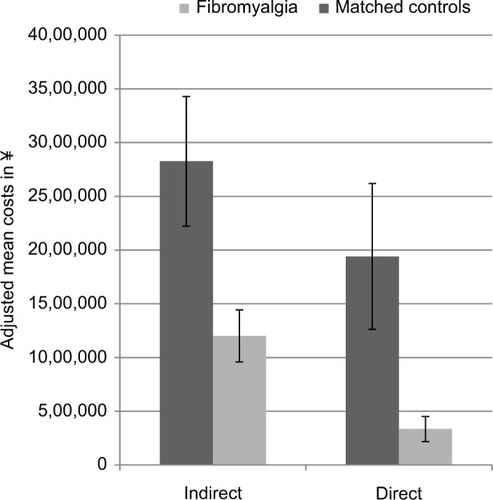

As a result of greater work productivity loss and health care resource use, indirect and direct costs were higher among respondents with fibromyalgia than among those without fibromyalgia. In particular, those with fibromyalgia incurred indirect costs that were more than twice as high (adjusted means =¥2,826,395 [CI =¥2,223,091–¥3,593,425] vs ¥1,201,547 [CI =¥959,917–¥1,503,999]) and direct costs that were nearly six times as high (adjusted means =¥1,941,118 [CI =¥1,262,639–¥2,984,177] vs ¥335,140 [CI =¥217,998–¥515,227]), all with P<0.001 ().

Figure 6 Adjusted mean indirect and direct costs (in ¥) by those diagnosed with fibromyalgia vs nonfibromyalgia matched controls.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

Compared with Japanese adults without fibromyalgia, those with fibromyalgia had lower scores on all SF-36v2/SF-12v2 component summary scores and health domain scores, as well as SF-6D health utilities. Notably, differences on MCS and PCS and SF-6D health utilities far exceeded the minimally important difference thresholds, demonstrating clinically meaningful differences in HRQoL between those with fibromyalgia and without fibromyalgia. In addition, those with fibromyalgia experienced substantially greater incidences of sleep difficulties relating to symptoms of insomnia. Hence, among Japanese adults, the findings indicated that fibromyalgia was associated with significant decreases in HRQoL.

Economic burden was also substantially greater for adults with fibromyalgia than for those without fibromyalgia. Work productivity and activity impairment were experienced >60% of the time by adults with fibromyalgia, which was more than twice the amount experienced by those without fibromyalgia. Moreover, those with fibromyalgia used health care resources to a much greater extent, with 13 times as many ER visits, seven times as many hospitalizations, and three times as many health care provider visits. In turn, adults with fibromyalgia incurred substantially higher indirect and direct costs.

The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the current study sample (0.1%) was much smaller than the prevalence (2.1%) reported by Nakamura et al in their epidemiologic Internet survey on fibromyalgia conducted in Japan.Citation5 Yet, this latter estimate was more in accord with those reported in Western countries, such as the USA (1.75%),Citation11 Germany (2.1%),Citation31 France (1.6%),Citation32 and the UK (5.4%).Citation33 One likely explanation for these differences in reported prevalence is that in the current study prevalence of fibromyalgia was determined by respondents’ self-reported physician diagnosis of fibromyalgia, whereas in the other studies ACR diagnostic criteria were used to estimate the prevalence.

There are likely vast differences in diagnosis rates and actual prevalence of fibromyalgia as there is some evidence that fibromyalgia may be under-diagnosed in Japan. In particular, one study showed that only half of Japanese workers who met the ACR criteria for a diagnosis of fibromyalgia had reported their chronic widespread pain symptoms to a physician within the prior year. Among these individuals, only 12.5% were actually diagnosed by a physician.Citation34 In addition, among Japanese physicians who had previously treated fibromyalgia patients, less than half (44.2%) self-reported wanting to accept more patients with this chronic pain condition.Citation35 Furthermore, cross-national data showed that Japan had the lowest rate of pain reported (4.4%) and treated (26.3%), compared to other developed countries, including the USA (23.8% experienced pain and 40.1% treated) and Europe (including the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain; 20.2% experienced pain and 47.0% treated).Citation36 Therefore, underdiagnosis and low acceptance of patients with fibromyalgia by physicians coupled with low pain reporting among patients may hinder the ability of Japanese patients to obtain a diagnosis and receive treatment for fibromyalgia.

Other study findings were largely consistent with the existing research on fibromyalgia. For example, findings were consistent with epidemiological research demonstrating the higher prevalence of fibromyalgia among Japanese women, compared to men.Citation5 This study’s results were also in accord with prior research, outside of Japan, showing that the prevalence of sleep difficulties was significantly higher for adults with fibromyalgia than for matched controls; poor sleep quality has also been found to relate to lower HRQoL.Citation3 The findings likewise aligned with previous studies highlighting the health and economic burden of fibromyalgia, although not specific to the Japanese population. In particular, fibromyalgia has been associated with multiple comorbidities,Citation4 as well as decreases in most aspects of HRQoL.Citation8 Moreover, high direct costs, due to health care resource use, and indirect costs, due to unemployment and work productivity loss, have been ascribed to fibromyalgia.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12

The present study makes a number of important contributions to the literature on fibromyalgia. In particular, prior research had examined only a small range of outcomes, so the full extent of the burden associated with fibromyalgia in Japan was unknown. Furthermore, because of the aggregation of chronic pain conditions, other relevant studies had been unable to provide an indication of the burden specific to fibromyalgia in Japan. Overall, the present research was able to more comprehensively clarify, within a single study, the degree of fibromyalgia-related burden in Japan on a wide variety of health and economic outcomes.

Limitations

As previously discussed, there may be underdiagnosis of fibromyalgia in Japan. If this is indeed the case, the current study may actually provide an underestimate of the burden of fibromyalgia in Japan. Thus, the estimate of the minimum direct and indirect costs attributed to fibromyalgia in Japan in the current study may be underestimated. Future studies may provide more accurate cost estimates by using the ACR diagnostic criteriaCitation1 for identifying fibromyalgia in Japan, rather than relying on self-reported diagnosis rates.

Among the fibromyalgia treatments currently used by the patients in the present study, branded pregabalin was most commonly used. It is important to note that the indirect (costs due to work productivity loss) and direct (costs due to health care resource use) cost estimates presented in the current study did not include pharmacy costs. Thus, we cannot ascertain whether pregabalin, or any other medication, contributed to the economic burden of fibromyalgia in Japan.

In addition, there are several other limitations in the current study. The study’s results may be limited due to recall bias, given that outcomes were self-reported instead of clinically determined. To verify the self-reported responses, future research should incorporate independent data, such as data from patients’ medical charts. Self-selection effects may likewise have biased results. For instance, younger, healthier, and/or wealthier respondents may have been more likely to participate in the study, as a function of greater access to the required technology and/or motivation to complete online surveys. Indeed, at least compared with one other fibromyalgia study in Japan, there were a greater proportion of less severe fibromyalgia patients in the current study. Among fibromyalgia patients in the current study, 21% reported severe pain; however, in the study by Nakamura et al, 52.5% reported severe pain (ie, a rating of 7–10 on the numeric pain rating scale).Citation5 If the current study sample truly has an underrepresentation of severe fibromyalgia patients, then the associations found between fibromyalgia and the health and economic outcomes examined may be underestimated. A prospective study can potentially use alternative means of survey administration, such as a paper-and-pencil format, to collect data from a broader sample of Japanese adults who may lack the access or capability to complete an online survey. In addition, generalizability of the burden associated with fibromyalgia based on a sample size of 128 may be limited. However, the study findings demonstrating the substantial humanistic and economic burden associated with fibromyalgia in Japan are in line with studies conducted in the USA and some with much larger sample sizes.Citation11,Citation12 Because of the cross-sectional, correlational design of this study, the results may not reflect longer term changes in the burden of fibromyalgia, and causal inferences cannot be made. A longitudinal study can help to address some of these shortcomings. Finally, the NHWS is designed to be a broad representative of the Japanese adult population, yet the degree to which the NHWS represents the adult population with fibromyalgia cannot be confirmed. Therefore, further research is required to corroborate these findings.

Conclusion

Japanese adults with fibromyalgia evidenced substantially poorer health status and sleep quality than those without fibromyalgia. In addition, Japanese adults with fibromyalgia experienced significantly greater lost work productivity and health care use than those without fibromyalgia that resulted in significantly higher costs. Thus, the findings underscored the health and economic burden associated with fibromyalgia in Japan. Improving the rates of diagnosis and treatment for this chronic pain condition may be helpful in addressing this considerable burden.

Author contributions

Nozomi Ebata, Patrick Hlavacek, Joseph C Cappelleri, Alesia Sadosky, and Marco DiBonaventura contributed to study design and interpretation of results. Lulu K Lee contributed to all aspects of study design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to review and revision and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the literature review and editing assistance of Martine C Maculaitis, on behalf of Kantar Health, with funding from Pfizer, Inc.

Disclosure

Lulu K Lee is an employee of Kantar Health and received funding from Pfizer, Inc. to conduct and report this study. At the time this study was conducted, Marco DiBonaventura was an employee of Kantar Health; currently, he is an employee of Ipsos. Nozomi Ebata, Patrick Hlavacek, Joseph C Cappelleri, and Alesia Sadosky are also employees of Pfizer, Inc., which funded this study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WolfeFClauwDJFitzcharlesMThe American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severityArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)20106260061020461783

- VijBWhippleMOTepperSJMohabbatABStillmanMVincentAFrequency of migraine headaches in patients with fibromyalgiaHeadache20155586086525994041

- WagnerJDiBonaventuraMDChandranABCappelleriCThe association of sleep difficulties with health-related quality of life among patients with fibromyalgiaBMC Muskuloskelet Disord201213199

- VincentAWhippleMOMcAllisterSJAlemanKMSt SauverJLA cross-sectional assessment of the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions and medication use in a sample of community-dwelling adults with fibromyalgia in Olmstead County, MinnesotaBMJ Open20155e006681

- NakamuraINishiokaKUsuiCAn epidemiological internet survey of fibromyalgia and chronic pain in JapanArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)2014661093110124403219

- UsuiCHattaKArataniSThe Japanese version of the modified ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and the Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale: reliability and validityMod Rheumatol20132384685023001748

- CamposRPVazquezMIRHealth-related quality of life in women with fibromyalgia: clinical and psychological factors associatedClin Rheumatol20123134735521979445

- SchaeferCMannRMastersETThe comparative burden of chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia in the United StatesPain Pract201616556557925980433

- SchaeferCChandranAHufstaderMThe comparative burden of mild, moderate and severe fibromyalgia: results from a cross-sectional survey in the United StatesHealth Qual Life Outcomes201197121859448

- TanderBCengizKAlayliGIlhanliICanbazSCanturkFA comparative evaluation of health related quality of life and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and rheumatoid arthritisRheumatol Int20082885986518317770

- WalittBNahinRLKatzRSBergmanMJWolfeFThe prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview SurveyPLoS One201510e013802426379048

- ChandranASchaeferCRyanKBaikRMcNettMZlatevaGThe comparative economic burden of mild, moderate, and severe fibromyalgia: results from a retrospective chart review and cross-sectional survey of working-age U.S. adultsJ Manag Care Pharm20121841542622839682

- SadoskyABDiBonaventuraMCappelleriJCEbataNFujiiKThe association between lower back pain and health status, work productivity, and health care resource use in JapanJ Pain Res2015811913025750546

- WHO Expert ConsultationAppropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategiesLancet2004363940315716314726171

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis1987403733833558716

- WareJEKosinkskiMKellerSDA 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validityMed Care1996342202338628042

- WareJEKosinskiMTurner-BowkerDMGandekBHow to Score Version 2 of the SF-12® Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version)Lincoln, RIQuality Metric Incorporated2002

- BrazierJRobertsJDeverillMThe estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36J Health Econ20022127129211939242

- WaltersSJBrazierJEComparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6DQual Life Res2005141523153216110932

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)Washington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- ReillyMCZbrozekASDukesEMThe validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrumentPharmacoeconomics1993435336510146874

- LoflandJHPizziLFrickKDA review of health-related workplace productivity loss instrumentsPharmacoeconomics20042216518414871164

- Economic and Social Research InstituteEffect analysis of outpatient visits optimization measures in the medical insurance systemTokyoEconomic and Social Research Institute2003 Available from: http://www.esri.go.jp/jp/archive/tyou/tyou002/tyou002a.pdfAccessed February 5, 2016 Japanese

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare2013 Fiscal Year Trends of Medical ExpensesTokyoMinistry of Health, Labour and Welfare2014 Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/medias/year/13/dl/iryouhi_data.pdfAccessed February 5, 2016 Japanese

- oecd-ilibrary.org [homepage on the Internet]Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators: Average length of stay in hospitalOrganisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)2011 Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/49105858.pdfAccessed February 5, 2016

- ParsonsLSReducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniquesPoster presented at: SAS Users Group InternationalApril 22–25; 2001Long Beach, CA

- GreenlandSModelling variable selection in epidemiologic studiesAm J Public Health19897340349

- CohenJCohenPWestSGAikenLSApplied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciencesMahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum2003

- ParsonsLSPerforming a 1:N case-control match on propensity scorePoster presented at: SAS Users Group InternationalApril 22–25; 2001Long Beach, CA

- AustinPCSome methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulationsBiom J200951117118419197955

- WolfeFBrahlerEHinzAHauserWFibromyalgia prevalence, somatic symptom reporting, and the dimensionality of polysymptomatic distress: results from a survey of the general populationArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)20136577778523424058

- PerrotSVicautEServantDRavaudPPrevalence of fibromyalgia in France: a multi-step study research combining national screening and clinical confirmation: the DEFI study (Determination of Epidemiology of Fibromyalgia)BMC Musculoskelet Disord20111222421981821

- FayazACroftPLangfordRMDonaldsonLJJonesGTPrevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studiesBMJ Open20166e010364

- TodaKThe prevalence of fibromyalgia in Japanese workersScand J Rheumatol20073614014417476621

- HommaMIshikawaHKiuchiTAssociation of physicians’ illness perception of fibromyalgia with frustration and resistance to accept patients: a cross-sectional studyClin Rheumatol20163541019102725085273

- GorenAMould-QuevedoJDiBonaventuraMDPrevalence of pain reporting and associated health outcomes across emerging markets and developed countriesPain Med2014151880189125220263