Abstract

Background

Chronic back pain is relatively resistant to unimodal therapy regimes. The aim of this study was to introduce and evaluate the short-term outcome of a three-week intensive multidisciplinary outpatient program for patients with back pain and sciatica, measured according to decrease of functional impairment and pain.

Methods

The program was designed for patients suffering from chronic back pain to provide intensive interdisciplinary therapy in an outpatient setting, consisting of interventional injection techniques, medication, exercise therapy, back education, ergotherapy, traction, massage therapy, medical training, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, aquatraining, and relaxation.

Results

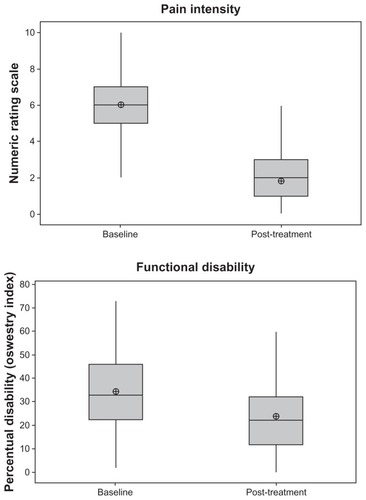

Based on Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) scores, a significant improvement in pain intensity and functionality of 66.83% NRS and an ODI of 33.33% were achieved by our pain program within 3 weeks.

Conclusion

This paper describes the organization and short-term outcome of an intensive multidisciplinary program for chronic back pain on an outpatient basis provided by our orthopedic department, with clinically significant results.

Introduction

Chronic back pain is the most common cause of long-term disability in the middle-aged population in most countries. About 20% of the German population suffers from back pain, and 10% have pain of high intensity causing functional impairment.Citation1–Citation3 Back pain that persists for longer than 3 months is deemed to be chronic. It significantly affects all aspects of life and, because of its multitude of biopsychosociocultural components, is relatively resistant to unimodal therapy regimes.Citation4 Together with inpatient and acute care, the special orthopedic pain management program in the Department of Orthopaedics at the University of Ulm provides an intensive interdisciplinary approach to treatment of patients with chronic back pain on an outpatient basis. The purpose of this paper was to present a retrospective analysis and critical evaluation of this program.

Materials and methods

This retrospective analysis included 160 subjects from a total of 184 patients treated in our special orthopedic pain management program in 2010. There were 70 male and 90 female patients with a minimum duration of back pain of three months and persistence after standard medical treatment, who met the inclusion criteria for the special orthopedic pain management program described below (see and ).

Table 1 Program inclusion criteria

Table 2 Program exclusion criteria

Unlike other pain programs, we do not exclude patients with failed back surgery syndrome or rheumatic disease, and do not set age limits as long as the above-mentioned inclusion criteria are met. Baseline and outcome parameters for pain and disability after three weeks of the program were assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaires. Patients were asked to complete these questionnaires and were also advised to complete a personal pain diary during the program, whereby pain intensity was rated on the NRS four times per day.

The NRS is a well accepted tool for assessment of the intensity of back pain, with 11 possible grades from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain).Citation5 The ODI is also a well accepted outcome instrument used in the management of spinal disorders, and has good validity and reliability.Citation5–Citation8 Performance of daily activities influenced by pain is evaluated using a 10-item questionnaire. Patients grade their impairment and pain, and indicate the extent to which pain influences their self-care, lifting, walking, sleeping, standing, sitting, traveling, social activity, and sexual function. Each item is scored on a six-point scale (0–5). The score for each item is added and divided by the total possible score (50, if all questions were answered). The possible outcome varies between 0% and 100% impairment.

The primary research question was whether there was a clinical benefit from this program, as indicated by changes in NRS and ODI scores between baseline and on completion of the program, and if the conservative treatment could achieve a so-called “good outcome”, ie a clinically relevant change. We defined a “good outcome” as a minimum clinically important change in pain intensity of at least two points on the NRS and of at least 10 points on the ODI, consistent with previous studies in patients with spinal disorders.Citation9,Citation10 Further, our results were compared with the results of other programs reported in the literature.

Special orthopedic pain management program

Our pain management program was designed for patients suffering from chronic back pain to provide intensive interdisciplinary therapy in an outpatient setting and consists of interventional injection techniques, medication, exercise therapy, back school, ergotherapy, traction, massage therapy, medical training, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, aquatraining, relaxation, and further techniques as described below. The goal is to deliver an intensive combination of activating and relaxing cycles. An individual therapy plan is designed at the beginning of the program for each patient, depending on their disorder, chronification, and other factors, including overall fitness, disability, and comorbidity. We combine group therapy with individualized treatment approaches. If indicated, further psychosomatic exploration and treatment is embarked on.

Our basic pain management team consists of an experienced orthopedic surgeon, who assessed patients twice daily and administered spinal injections as necessary, an anesthetist/algesiologist, and a group of 5–6 experienced physical therapists who provide both individual and group treatments. Each patient’s history, treatment program, and progress are discussed by the team, at meetings held 2–3 per week.

The duration of the program is three weeks, and includes work days between 8 am and 5 pm. About 3–4 patients who meet the inclusion criteria are added into the program weekly, so the group always consists of 10–12 patients. This protocol allows group treatment to be as intensive as individual therapy. Approximately 185–200 patients are treated each year in our pain management program. The following is an overview of the therapy provided for each patient.

Medical treatment

The medical component of the program determines the indication for treatment, and includes a baseline examination, documentation, planning of the treatment regime, control and supervision of each patient’s progress twice daily, with spinal injection and modification of analgesia as appropriate. In our department, spinal injection procedures are performed by an experienced surgeon, who also heads the program. Approximately 900–1000 epidural injections, 300–400 periradicular injections, and at least 1000 facet joint injections are performed per year in our department. The indication for spinal injection is determined by the orthopedic surgeon, who is also the performing interventionalist. The decision is based on daily patient status, pain intensity, physical examination, findings on radiographic and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, and chronification grade. All spinal injections are performed using computed tomographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Facet joint injections can be performed as part of treatment or to confirm facetogenic pain, as seen in spondyloarthritis, scoliosis, spondylolisthesis, or even osteoporosis. Nerve root injections are performed into the extraforaminal region or via an epidural-perineural approach in cases of nerve root compromise in patients with disc herniation, lateral spinal stenosis, or failed back surgery syndrome. Sacroiliac joint injections are performed in patients with low back pain and glutalgia originating from the sacroiliac joints as seen in seronegative spondyloarthropathy, sacroiliac dysfunction, limb length discrepancy, or after hip joint arthroplasty. For epidural injections into the cervical or lumbar spine we prefer the interlaminar approach in cases of spinal stenosis, unisegmental or multisegmental disc herniation, failed back surgery syndrome, and osteochondrosis. In cases of severe narrowing of the interlaminar gap (severe degeneration, osteoporosis, following fusion surgery) we use a transforaminal or epidural sacral approach. We limit the number of injections and exposure to radiation and corticosteroids (maximum 100–120 mg triamcinolone), performing 2–8 injections per patient. For therapeutic purposes, we use a combination of triamcinolone (20–40 mg per injection) and ropivacaine. When performed for diagnostic purposes, only ropivacaine is used. We use pulsed fluoroscopic guidance to limit radiation exposure in image-guided injections, and low-dose protocols in computed tomography guidance.

During the program, the medication intake of each patient, especially analgesics, is analyzed and modified as necessary by the physician, depending on pain intensity, comorbidities, side effects, and concomitant medication. We use a standardized pain diary to monitor improvement on the 10-point NRS four times per day. A pain diary also identifies circadian variation in pain more easily. First-line treatment of nonopioid analgesics and myorelaxants is provided when lower pain intensity is reported. In cases of high intensity pain, we perform spinal injections, add opioid analgesics to the medication, or even perform morphine rotation. Concomitant antidepressants or anticonvulsants are used in rare cases. In most cases, there is a decrease in analgesics intake during the program, but there are also cases when analgesics are changed, modified, or added.

Exercise therapy

Most studies of exercise treatment have found good results for reduction in intensity of back pain, ranging between 10% and 50%.Citation11 Exercise improves range of motion, muscle strength, posture, cardiovascular endurance, and sensitivity to pain. In our program, patients participate in intensive daily exercise consisting of cycles of physical therapy, medical training therapy, aerobic training, and aquatraining under supervision, followed by relaxation, massage, or spa therapy.

Ergotherapy

Each patient in our program learns how to adapt his/her workplace and home ergonomics on an individual basis depending on the extent of their disability.

Back education

Patients participate in an intensive back education program, which improves posture, reduces pain, and teaches them how to avoid overload and pain during activities of daily living.

Physical therapy

A growing body of evidence indicates the efficacy of physical therapy in the treatment of back pain. Every patient receives an intensive combination of spa therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, fango sheets, massage, manual therapy, stretching exercise, breathing gymnastics, traction, and thermal therapy, depending on the diagnosis and the patient’s response. The goals are relaxation and detonization, pain reduction, and increased blood perfusion, in combination with activating cycles of exercise.

Behavioral management

The purpose of behavioral management is to modify the patient’s perception of their pain, to reduce stress, and to learn relaxation techniques. The cycles are integrated twice per week for every patient, but can be varied on an individual basis. Behavioral management is the domain of physiotherapists in a group setting.

Psychosomatic therapy

Depending on the degree of chronification and psychological cofactors, patients may undergo psychosomatic exploration and therapy in our program. Group psychotherapy is performed by a psychologist specialized in psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy, focusing on psychosomatic and behavioral therapy, relaxation, and pain perception. The individualized approach is optional, although is used with increasing frequency. Patients are evaluated individually by the psychologist using the standardized interview method devised by Kernberg and, if indicated, are treated in one or two sessions per week.Citation12 If further treatment is needed, patients are advised to have further therapy sessions. The treatment regime and the individual frequency of treatments may vary, depending on the degree of disability and actual pain ().

Table 3 Frequency of treatment modalities in our intensive interdisciplinary outpatient pain management program

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), IBM software for descriptive statistics, and the Mann-Whitney U-test (confidence interval [CI] 95% and α = 0.05) to identify any statistically significant differences in NRS and ODI scores for low back pain before and after the program. Twenty-four incomplete datasets were excluded from the study.

Results

The 160 patients included in this study had a mean age of 57.18 ± 10.89 (range 22–82) years. Mean baseline NRS score was 6.03 ± 1.69 (95% CI, 5.77–6.29). Mean baseline ODI score was 34.39% ± 15.85% (95% CI, 31.93–36.85). After treatment, the mean NRS score was 2.00 ± 1.61 (95% CI, 1.75–2.25) and the mean ODI score was 24.21 ± 15.4% (95% CI, 21.82–26.60). The mean difference between before and after treatment scores on the NRS was 4.00 ± 2.01 points (95% CI, 2.69–4.31), representing a 66.83% reduction, and a reduction in ODI score of 11.00 ± 10.97 points (95% CI, 9.3–12.7), representing a 33.33% reduction. Baseline and outcome characteristics are shown in (see also ).

Figure 1 and 2 Baseline to post-treatment improvement of pain and disability. Box plot legend: Upper whisker – Extends to the maximum data point; interquartile range box, middle 50% of the data; Top line – Q3 (third quartile). 75% of the data are less than or equal to this value. Middle line – Q2 (median); Target – mean value; Bottom line – Q1 (first quartile). 25% of the data are less than or equal to this value. Lower whisker – Extends to the minimum data point.

Table 4 Baseline and outcome characteristics

Complications

There were no significant complications (eg, infection, paresis, allergic reaction, or arrhythmia) in our patients during the study. The most frequent side effect of intensive exercise therapy was a temporary increase in muscle soreness, often interpreted as pain. This effect was seen on days 3–5 of the first week of therapy. Muscle soreness is self-limiting, and has been well described in other reports of intensive exercise treatment.Citation11 From the 24 incomplete datasets, two withdrawals due to respiratory tract infection were identified, along with two exclusions because of pain escalation at examination on the first day of the program. These patients underwent intensive hospital care for further diagnostics and intravenous analgesia. Vasovagal reactions to pain injections occurred in five patients, as well as hypertonia. These side effects were self-limiting.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis indicates that good improvement in pain and functionality, as reflected by a change in visual analog scale score of 4 points (66.83%) and a change in ODI score of 11 points (33.33%), was achieved by patients in our pain program within three weeks. We did not analyze parameters like spinal mobility, and did not follow them up, because they are not representative. Our program also includes patients with ankylosing spinal diseases, such as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and spondylitis ankylosans, and although we achieve good results for pain and functionality in these conditions, spinal mobility parameters would not be able to be improved in such patients. The gender distribution (90 females, 70 males) is consistent with the known fact that spinal disorders are more common in women than in men.Citation13

To define a good clinical result in pain patients is difficult. Individual patient factors like expectations, age, pain intensity, diagnosis, comorbidity, and functional impairment all play a role. The principal target of interdisciplinary treatment is to increase function in the patient’s occupational and private life, but each patient has different priorities regarding functional impairment. While younger patients consider restoration of work status, social activities, travel, and even sexual function to be important, older people are more likely to value basic functioning in the home and being able to walk. Most of these items are covered in the ODI, but the relevant data in the international literature regarding clinically significant change are inconsistent. While many researchers suggest a 4–10-point difference to determine significant change, there are also studies suggesting a range of 10.5–15 points.Citation14–Citation18 A raw change of −1.74 on the NRS, corresponding to a change of −27.9%, was reported by Farrar et al as clinically significant improvement.Citation17 Based on statistical research, Hagg et al defined a minimal clinically significant reduction in ODI of approximately 10 points, whereas Mannion et al identified an 18% reduction of the baseline score (defined for spinal surgery outcomes) and a change of approximately 20 points on a 100-point visual analog scale, which corresponds to a minimal change of 2 points on the 11-point scale NRS scale.Citation10,Citation19 Maughan and Lewis reported the smallest detectable change to be 2.4 points for the NRS and 17 points for the ODI, which is comparable with the clinical interpretation by an expert consensus panel proposing 2 points for the NRS and 10 points for the ODI.Citation5,Citation9,Citation20 Fritz and Irrgang proposed that a 6-point difference in the ODI was the minimal clinically important difference.Citation15 Childs et al concluded from their calculations that a 2-point change on the NRS is necessary to exceed statistical error and to be considered clinically meaningful. Citation21 According to IMMPACT (Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials), a 10%–20% reduction in the baseline NRS score reflects a minimal important change and a reduction of 30% or more represents a clinically important difference.Citation22 The results seen in our intensive multidisciplinary outpatient program cohort fulfilled all of these criteria. There is a large amount of literature about the efficacy of conservative treatment for chronic back pain, as shown in .

Table 5 Sample comparison of efficacy of conservative therapies in chronic low back pain

Evidence for the beneficial effects of intensive interdisciplinary programs on pain, functionality, and return to work is accumulating. Intensive (>100 hours) daily interdisciplinary rehabilitation (defined as an intervention with a physical component plus a psychological, social, and/or occupational component) seems to be superior to noninterdisciplinary rehabilitation or usual care for improving short-term and long-term functional status and pain, return to work, and reducing intake of pain medication.Citation41–Citation47 Less intensive interdisciplinary approaches seem to be less associated with improvement in pain or function compared with noninterdisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation or usual care.Citation48

Intensive interdisciplinary treatment has both benefits and limitations. Despite its efficacy, there is still a lack of standardization regarding the frequency and amount of treatment needed. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has summarized the components of interdisciplinary treatment as consisting of four main elements, ie, medical care, physical reconditioning, behavioral medicine, and education, with team meetings and individualized therapies, undertaken for two hours twice a week to eight hours on five days a week for six weeks.Citation49,Citation50 In the literature, intensive programs are understood to include more than 100–120 hours of therapy, but there is no standard terminology. One major benefit of interdisciplinary pain programs lies in the biopsychosocial approach, which focuses on functional restoration and combines a large amount of treatment modalities. Also, larger groups of patients can undergo this therapy in contrast to surgical or unimodal conservative treatments, making this therapy cost-effective, especially in patients with significant functional impairment.Citation41 On the other hand, to provide individual therapy, group sizes must be limited. Another limitation is the age of the patient. Most intensive treatments focusing on functional restoration include only patients of working age, for whom the initial target is reintegration into the workforce. We do not exclude geriatric patients from our program. Despite this, overall fitness of our patients remains a limiting factor, and so excludes many elderly patients. Other limitations concern patients who are immigrants with language problems, who are not suitable for behavioral or educational programs in this setting. There has been an increase in this patient group, as well as the need for an interdisciplinary approach.

We have also seen an increase in uncontrolled intake of analgesics among patients suffering from back pain. An alarming long-term intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics is seen, especially in the elderly population, who have an increased risk of potential side effects with these agents. According to our results, and comparing them with those in the current literature, the short-term results of our interdisciplinary outpatient pain management program indicate a clinically significant improvement in pain and functionality.

Conclusion

Despite their efficacy, interdisciplinary treatments for back pain still lack standardization regarding the amount and intensity of the therapy regime. The use of spinal injections is a good example. Based on our experience, we use spinal injections as supportive therapy and to confirm whether pain is facetogenic, discogenic, or radicular, or if it is originating from the sacroiliac joints. Despite the controversial evidence, we see positive results in terms of symptom control in most patients when the indication is strictly controlled. Another example is the intensity of the psychologic/psychosomatic treatment. We are seeing an increasing frequency of individual psychological approaches in addition to group therapy, which is well accepted in most cases. Also, a balance in the proportion of active and passive treatments plays an important role in interdisciplinary therapy. Patients suffering from chronic pain prefer passive treatment, which is helpful in symptom control. On the other hand, one of the main aims of treatment is to increase the activity levels of the patient, which can only be achieved with adequate active therapies.

Here we describe an intensive outpatient interdisciplinary program for the management of chronic back pain which appears to have good short-term clinical results in terms of reduction in functional disability and pain relief. The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature, the lack of a control group, and the short duration of follow-up. However, one important advantage is the inclusion of elderly patients suffering from chronic back pain. Further investigation is needed to define the long-term results, improvement of isolated spinal disorders, interindividual differences in pain ratings, and their dependence on chronification, age, gender, occupation, coping strategies, fear-avoidance beliefs, and possibly immigration status.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BellachBMEllertURadoschewskiMEpidemiologie des Schmerzes – Ergebnisse des Bundes-Gesundheitssurveys 1998 (Epidemiology of pain: Results of a national health-survey 1998)Bundensgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung – Gesundheitsschutz200043424431 German

- SchmidtCOKohlmannTWhat do we know about the symptoms of back pain? Epidemiological results on prevalence, incidence, progression and risk factorsZ Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb2005143292298 German15977117

- EckardtAPraxis LWS-Erkrankungen: Diagnosis und Therapie (Disorders of the lumbar spine: diagnosis and treatment)Heidelberg, GermanySpringer Medizin Verlag20111.123

- TurkDCClinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic painClin J Pain20021835536512441829

- MaughanEFLewisJSOutcome measures in chronic low back painEur Spine J2010191484149420397032

- FairbankJCPynsentPBThe Oswestry disability indexSpine2000252940295211074683

- BombardierCOutcome assessment in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disordersSpine2000253100310311124724

- JungeAMannionAFQuestionnaires for patients with back pain. Diagnosis and outcome assessmentOrthopäde200433545552 German

- OsteloRWde VetHCWClinically important outcomes in low back painBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol20051959360715949778

- HaggOFritzellPNordwallASwedish Lumbar Spine Study GroupThe clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back painEur Spine J200312122012592542

- RainvilleJHartiganCMartinezELimkeJJouveCFinnoMExercise as a treatment for chronic low back painSpine J2004410611514749199

- KernbergOSevere Personality Disorders: Psychotherapeutic StrategiesNew Haven, CTYale University Press1984

- FreburgerJKHolmesGMAgansRPThe rising prevalence of chronic low back painArch Intern Med200916925125819204216

- BeurskensAJde VetHCKokeAJResponsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instrumentsPain19966571768826492

- FritzJMIrrgangJJA comparison of a modified Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the Quebec back pain disability scalePhys Ther20018177678811175676

- StratfordPWBinkleyJSolomonPGillCFinchEAssessing change over time in patients with low back painPhys Ther1994745285338197239

- FarrarJTYoungJPLaMoreauxLWerthJLPooleRMClinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scalePain20019414915811690728

- DavidsonMKeatingJLA comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsivenessPhys Ther20028282411784274

- MannionAFJungeAGrobDDvorakJFairbankJCTDevelopment of a German version of the Oswestry Low Back Index. Part 2: sensitivity to change after spinal surgeryEur Spine J200615667315856340

- OsteloRDeyoRStratfordPInterpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back painSpine200833909418165753

- ChildsJRivaSFritzJResponsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back painSpine2005301331133415928561

- DworkinRTurkDWyrwichKInterpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain trials: IMMPACT recommendationsJ Pain2008910512118055266

- DescarreauxMNormandMCLaurencelleLDugasCEvaluation of a specific home exercise program for low back painJ Manipulative Physiol Ther20022549750312381971

- MannionAFMüntenerMTaimetaSDvorakJComparison of three active therapies for chronic low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial with one-year follow-upRheumatology20014077277811477282

- MurtezaniAHundoziHOrovcanecNSllamnikuSOsmaniTA comparison of high intensity aerobic exercise and passive modalities for the treatment of workers with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trialEur J Phys Rehabil Med20114735936621602759

- BrinkhausBWittCMJenaSAcupuncture in patients with chronic low back painArch Intern Med200616645045716505266

- BormanPKeskinDBodurHThe efficacy of lumbar traction in the management of patients with low back painRheumatol Int200323828612634941

- FrostHKlaber MoffetJAMoserJSFairbankJCTRandomised controlled trial for evaluation of fitness programme for patients with chronic low back painBr Med J19953101511547833752

- Van der VeldeGMierauDThe effect of exercise on percentile rank aerobic capacity, pain, and self-rated disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a retrospective chart reviewArch Phys Med Rehabil2000811457146311083348

- RydeardRLegerASmithDPilates-based therapeutic exercise: effect on subjects with nonspecific chronic low back pain and functional disability: a randomized controlled trialOrthop Sports Phys Ther200636472484

- WaagenGNHaldemanSCookGLopezDDeBoerKFShort-term trial of chiropractic adjustments for the relief of chronic low back painManual Med198626367

- GibsonTGrahameRHarknessJWooPBlagravePHillsRControlled comparison of short-wave diathermy treatment with osteopathic treatment in nonspecific low back painLancet19851125812612860453

- TrianoJJMcGregorMHondrasMABrennanPCManipulative therapy versus education programs in chronic low back painSpine1995209489557644961

- AssendelftWJMortonSCYuEISuttorpMJShekellePGSpinal manipulative therapy for low-back painCochrane Database Syst Rev20041CD00044714973958

- TsauoJYChenWHLiangHWJangYThe effectiveness of a functional training programme for patients with chronic low back pain – a pilot studyDisabil Rehabil2009311100110619802926

- RainvilleJJouveCAHartiganCMartinezEHiponaMComparison of short- and long-term outcomes for aggressive spine rehabilitation delivered two versus three times per weekSpine J2002240240714589260

- SahinNAlbayrakIDurmusBUgurluHEffectiveness of back school for treatment of pain and functional disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trialJ Rehabil Med20114322422921305238

- LukKDKWanTWMWongYWA multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective studyJ Orthop Surg201018131138

- HazardRGFenwickJWKalischSMFunctional restoration with behavioral support: a one-year prospective study of patients with chronic low back painSpine1989141571612522243

- EdwardsBCZusmanMHardcastlePTwomeyLO’SullivanPMcLeanNA physical approach to the rehabilitation of patients disabled by chronic low back painMed J Aust19921561671711532045

- NagelBKorbJInterdisciplinary treatment. Long-lasting, effective and cost-effectiveOrthopäde200938910912

- GuzmanJEsmailRKarjalainenKMalmivaaraAIrvinEBombardierCMultidisciplinary bio-psycho-social rehabilitation for chronic low-back painCochrane Database Syst Rev20021CD00096311869581

- GuzmanJEsmailRKarjalainenKMalmivaaraAIrvinEBombardierCMultidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic reviewBMJ20013221511151611420271

- BendixAFBendixTVaegtarKVLundCFrolundLHolmLMultidisciplinary intensive treatment for chronic low back pain: a randomized, prospective studyCleve Clin J Med19966362698590519

- BendixAFBendixTOstenfeldSActive treatment programs for patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective, randomized, observer-blinded studyEur Spine J199541481527552649

- AlarantaHRytokoskiURissanenAIntensive physical and psychosocial training program for patients with chronic low back pain. A controlled trialSpine19941913401349

- SmithMJAccountable disease management of spine painSpine J20111180781521840770

- TveitoTHysingMEriksenHLow back pain interventions at the workplace: a systematic literature reviewOccup Med200454313

- Agency for Healthcare Research and QualityEffective healthcare programTechnical brief: multidisciplinary pain programs for chronic non-cancer pain2011 Available from: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/212/760/TechBrief8_PainProgramsCancer_20110930.pdfAccessed March 14, 2012

- SchatmanMECampbellAChronic Pain Management: Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Program DevelopmentNew York, NYInforma Healthcare2007