Abstract

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are among the most effective antidepressants available, although their poor tolerance at usual recommended doses and toxicity in overdose make them difficult to use. While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are better tolerated than TCAs, they have their own specific problems, such as the aggravation of sexual dysfunction, interaction with coadministered drugs, and for many, a discontinuation syndrome. In addition, some of them appear to be less effective than TCAs in more severely depressed patients. Increasing evidence of the importance of norepinephrine in the etiology of depression has led to the development of a new generation of antidepressants, the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Milnacipran, one of the pioneer SNRIs, was designed from theoretic considerations to be more effective than SSRIs and better tolerated than TCAs, and with a simple pharmacokinetic profile. Milnacipran has the most balanced potency ratio for reuptake inhibition of the two neurotransmitters compared with other SNRIs (1:1.6 for milnacipran, 1:10 for duloxetine, and 1:30 for venlafaxine), and in some studies milnacipran has been shown to inhibit norepinephrine uptake with greater potency than serotonin (2.2:1). Clinical studies have shown that milnacipran has efficacy comparable with the TCAs and is superior to SSRIs in severe depression. In addition, milnacipran is well tolerated, with a low potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions. Milnacipran is a first-line therapy suitable for most depressed patients. It is frequently successful when other treatments fail for reasons of efficacy or tolerability.

Introduction

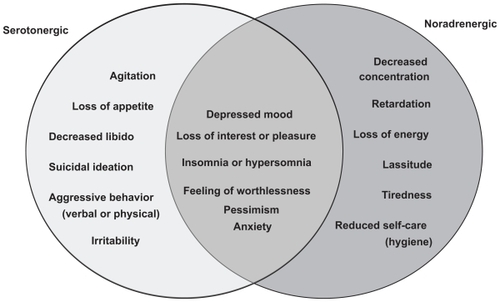

Depression is characterized by the presence of two core symptoms, depressed mood and anhedonia (decreased pleasure or interest). It is also accompanied, however, by a plethora of other signs and symptoms, such as changes in appetite and sleeping, fatigue and loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt, diminished ability to think or concentrate, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.Citation1 A relationship exists between the monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain, norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and the symptoms of major depressive disorder ().Citation2 Specific symptoms are thought to be associated with the increase or decrease of specific monoamines, implying the involvement of specific neurochemical mechanisms.

Figure 1 Relation between neurotransmitters and symptoms of depression.

Adapted from Nutt.Citation2

Virtually all antidepressants increase the synaptic concentrations of 5-HT and/or NE by blocking the reuptake of one or both of these neurotransmitters. The archetypal tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) block NE and 5-HT transporters to a varying extent depending on the particular compound.Citation3 Although they are among the most effective antidepressants available,Citation4 their poor tolerance and toxicity in overdose due to the involvement of other neurotransmitter systems make them difficult to use at effective doses.Citation5 The principal side effects of the TCAs are considered to be due essentially to their relatively high affinity for α1-adrenergic receptors, H1-histamine receptors, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors.Citation6 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which inhibit selectively the single neurotransmitter, 5-HT, are effective antidepressants. Although they have no affinity for α1-adrenergic receptors, H1-histamine receptors, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors, and are better tolerated than TCAs,Citation6 they have their own specific problems, such as aggravation of sexual dysfunction, interaction with coadministered drugs and, for many, a discontinuation syndrome.Citation7 In addition, some of them appear to be less effective than TCAs, with a number needed to treat for TCAs of about four compared with six for SSRIs in primary care.Citation8 The difference is most pronounced in more severely depressed patients.Citation9

In general, antidepressants achieve a response (≥50% reduction in baseline depression score) in less than 70% of patients and remission (a complete absence of depressive symptoms) in less than 50%. Increasing evidence of the importance of NE in the etiology of depressionCitation10 and the idea that “two actions are better than one” have led to the development of a new class of compounds that block the reuptake of both 5-HT and NE without the nonspecific, side effect-inducing receptor interactions of TCAs. This class, the serotonin (5-HT) and NE reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) comprises venlafaxine (and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine), duloxetine, and milnacipran.Citation11

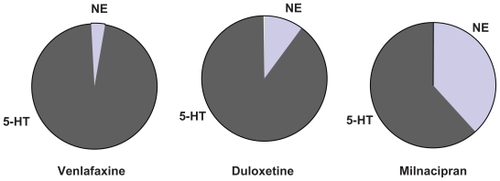

By definition, the SNRIs inhibit both 5-HT and NE transporters. There is, however, considerable difference in their selectivity for the two transporters ( and ). Venlafaxine has a much greater affinity for the 5-HT transporter than for the NE transporter. At low doses, it probably inhibits almost exclusively the 5-HT transporter, acting like a SSRI, with significant NE reuptake inhibition only occurring at higher doses. Duloxetine has a more balanced affinity, but is still more selective for the 5-HT transporter. Milnacipran is the most balanced SNRI, and some studies have even found it to be slightly more effective for the NE transporterCitation12 compared with the 5-HT transporter.

Figure 2 Selectivity of different serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the monoamine transporters. The segments represent the selectivity for the human norepinephine and serotonin (5-HT) transporters calculated according to data from Koch et al.Citation55

Table 1 Inhibition of binding to human monoamine transporters in vitro

There is frequently confusion between the terms “selectivity” and “potency”, which refer to two different entities. Potency reflects the concentration of the antidepressant inhibiting 50% of uptake or binding to the transporter, depending on the technique used. Thus from it can be seen that duloxetine is 154 times more potent than milnacipran at blocking the binding of 5-HT to the transporter (ie, 154 times more milnacipran is required to obtain the same effect). To block the binding of NE to its transporter, duloxetine is about 27 times more potent than milnacipran. If absorption, metabolism, distribution, brain penetration and distribution, and elimination were identical for the two drugs, it would be necessary to give 154 times more milnacipran than duloxetine to achieve the same effect on 5-HT reuptake and 27 times more milnacipran to have the same effect on NE reuptake. Of course the kinetic parameters vary considerably between these two compounds, and certain parameters are impossible to determine in humans (eg, brain penetration) and hence this calculation remains purely theoretical.

The selectivity of an antidepressant is the ratio of the potency values for NE and 5-HT reuptake inhibition (or inhibition of binding to the transporter). As shown in , milnacipran has a selectivity close to 1, duloxetine close to 10 (in favor of 5-HT), and venlafaxine close to 30. Thus, in a dose titration, when milnacipran starts to inhibit 5-HT reuptake, it also starts to inhibit NE reuptake; when it inhibits 5-HT reuptake by 50%, it also inhibits NE reuptake by approximately 50%, and so on. Increasing the dose does not alter the “nature” of the effect. At all doses it has an equivalent effect on the two neurotransmitters systems. In contrast, a dose titration with venlafaxine will give (eg, at 75 mg) an initial inhibition of 5-HT reuptake with no inhibition of NE uptake. Only at much higher doses (eg, 200–250 mg) is there any significant inhibition of NE reuptake, but at this dose the inhibition of 5-HT reuptake is already 100%. Thus, titrating venlafaxine changes the “nature” of its effect from a SSRI to a SNRI as the dose is increased. The situation with duloxetine is intermediate between milnacipran and venlafaxine.

There are some indications that the mechanism of milnacipran may be more complex than a simple action at the monoamine transporter, and thus is different from the other SNRIs. A study assessed the effect of milnacipran on the firing activity of dorsal raphe 5-HT neurons and locus coeruleus NE neurons using extracellular unitary recording in rats.Citation13 The authors concluded that milnacipran had profound effects on the function of 5-HT and NE neurons, but that the mechanism by which 5-HT neurons regained their normal firing during milnacipran treatment appears to implicate the NE system.

In a more recent study,Citation14 duloxetine and venlafaxine were found to increase 5-HT levels in the brainstem and 5-HT terminal areas, whereas milnacipran increased 5-HT levels only in the brainstem. Significant reductions in 5-HT turnover were observed in various forebrain regions, including the hippocampus and hypothalamus, after treatment with duloxetine or venlafaxine, but not after milnacipran. In addition, venlafaxine and duloxetine significantly increased dopamine (DA) levels and decreased DA turnover in the nucleus accumbens, whereas milnacipran only increased DA levels in the medial prefrontal cortex. The authors concluded that the effects of milnacipran were unique because it caused increases in DA in the medial prefrontal cortex and in 5-HT in the midbrain without any changes in monoamine turnover. They suggested that milnacipran might exert its therapeutic effects by activating the dopaminergic system in the medial prefrontal cortex, and that milnacipran was in this respect different from duloxetine and venlafaxine.

Some notable characteristics of milnacipran

In addition to its balanced action on the two monoamine transporters, preclinical and clinical studies have shown that milnacipran possesses certain characteristics which are relatively unusual in an antidepressant.

Milnacipran has no active metabolites. Unlike the majority of antidepressants, milnacipran is only metabolized to a very minor extent, with most of the administered drug being excreted in the urine either unchanged or as the inactive glucurono-conjugate.Citation15 Whereas most antidepressants interact with cytochrome P450 enzymes as inhibitors, inducers, or substrates,Citation16 milnacipran has been shown to be essentially devoid of interactions with any cytochrome P450 enzyme.Citation17 In addition, milnacipran binds to only a very limited extent (13%) to serum albumin.Citation15 Milnacipran, therefore, has a low risk of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions.

Depression is associated with sexual disturbances, including decreased libido, anorgasmia, and erectile problems. Since introduction of the SSRIs, it has become apparent that aggravation of sexual dysfunction is a frequent problem for patients taking these drugs, with some studies reporting rates as high as 75%.Citation18 Sexual dysfunction caused by SSRIs is related to stimulation of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors but its origin is complex and probably involves other systems as well.Citation19 VenlafaxineCitation20 and duloxetineCitation21,Citation22 also exacerbate sexual dysfunction at frequencies similar to those seen with SSRIs. A study using the Sexual Function and Enjoyment Questionnaire Citation23 showed no aggravation of sexual disturbance with milnacipran, which improved sexual function in parallel with improvement in other symptoms of depression.

Following abrupt discontinuation, most SSRIs, and paroxetine in particular, produce a number of adverse events, including dizziness, nausea, headache, paresthesia, vomiting, irritability, and nightmares.Citation24 Venlafaxine and duloxetine produce similar discontinuation emergent adverse events.Citation25,Citation26 A post hoc analysis of patients abruptly withdrawn from paroxetine or milnacipran as part of a double-blind comparative studyCitation27 showed that paroxetine produced significantly more discontinuation emergent adverse events than milnacipran. In addition, the nature of the adverse events differed between the two antidepressants, with patients withdrawn from paroxetine showing the classical symptoms of dizziness, anxiety, and sleep disturbance (insomnia and nightmares), while those withdrawn from milnacipran showed only increased anxiety. However, some discontinuation symptoms have been reported, and good clinical practice and regulatory authorities always recommend gradual discontinuation from any psychotropic drug.

Certain antidepressants are associated with clinically significant weight changes. In particular, some TCAs including amitriptyline, certain SSRIs including paroxetine, and other antidepressants, such as mirtazapine, are frequently associated with significant weight gain.Citation28 Data from a wide range of clinical trialsCitation29 have shown that 82% of patients taking milnacipran 100 mg/day for 3 months or more have no clinically significant weight change (defined as >5% of body weight). Of the remainder, 10% had clinically significant weight loss, while 8% had clinically significant weight gain.

Comparison of milnacipran with TCAs and SSRIs

Seven randomized, double-blind trials with similar designs have compared the efficacy and tolerability of milnacipran and TCAs in patients with major depression. At a dose of 100 mg/day the response rate with milnacipran (64%) was comparable with that of the TCAs (67%). In contrast with the TCAs, milnacipran was very well tolerated by patients.Citation30

A meta-analysis of studies comparing milnacipran at 100 mg/day with the SSRIs, fluvoxamine (200 mg/day) and fluoxetine (20 mg/day), in moderately to severely depressed hospitalized patients,Citation31 reported significantly more responders (64%) with milnacipran than with the two SSRIs (50%, P < 0.01) and a significantly higher remission rate (38.7% versus 27.6%, P < 0.04). Another study, published subsequent to this meta-analysis, compared milnacipran with paroxetine 20 mg/day in less severely depressed outpatients, and reported similar remission rates for the two antidepressants.Citation32

summarizes two studies, each comparing milnacipran with a SSRI, one in moderately to severely depressed hospitalized patients,Citation33 and the other in less severely depressed outpatients.Citation34 The two studies, which investigated two different SSRIs in different treatment settings, cannot be compared directly. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that milnacipran was associated with significant improvement in both studies. In contrast, the SSRIs led to an improvement comparable with that of milnacipran in the study of less severely depressed patients, but not in the study of patients with severe depression. Unlike milnacipran, SSRI treatment did not achieve the additional reduction in depression score needed in the severely depressed patients to reach response. Clearly this analysis is only indicative and the severity of depression was not the only factor that differed between the studies. Nevertheless, the results are compatible with other dataCitation34 suggesting that SSRIs may have a limited capacity for improving depressive symptoms, which becomes more evident in more severely depressed patients.

Table 2 Efficacy of milnacipran compared with SSRIs: comparison of two studies in mild-to-moderate and severe depression

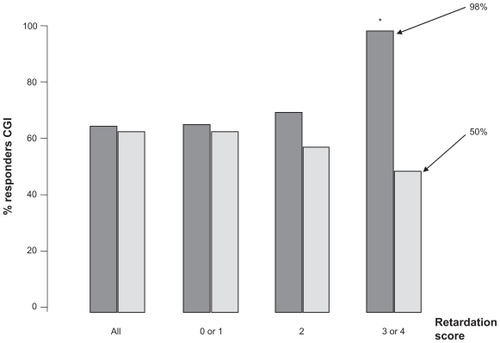

In the study comparing milnacipran with paroxetine 20 mg/day,Citation32 the overall efficacy of the two antidepressants was similar. However, milnacipran was significantly better than paroxetine in the subgroup of patients scoring maximally at baseline on the retardation-slowness of thought and speech, impaired ability to concentrate, and decreased motor activity factor (item 8) on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS, ). This is compatible with the finding that reduced noradrenergic neuronal tone is related to psychomotor retardation.Citation35 Furthermore, the selective NE reuptake inhibitor has been shown to improve psychomotor retardation systematically, even when other symptoms were not improved.Citation36 These data suggest that depressed patients with marked psychomotor retardation may benefit particularly from treatment with milnacipran.

Figure 3 Antidepressant response and psychomotor retardation. Retardation score was the score of item 8 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (slowness of thought and speech, impaired ability to concentrate, decreased motor activity). Dark grey columns = milnacipran; light grey columns = paroxetine. Figure drawn from data in Sechter et al.Citation32 *P < 0.05.

In studies comparing milnacipran with SSRIs, both compounds are generally well tolerated. The most frequent adverse event with both milnacipran and SSRIs is nausea, although this occurred less frequently with milnacipran.Citation31 As would be expected, adverse effects that are probably related to noradrenergic stimulation, such as dry mouth, sweating, and constipation, occur more frequently with milnacipran than with SSRIs, although the differences are not as large as might be expected.Citation31

A meta-analysis of all published studies comparing milnacipran with SSRIsCitation37 concluded that patients on milnacipran had the same probability of obtaining a clinical response as those on SSRIs. As with many meta-analyses, however, this global analysis grouped certain atypical studies which should have been analyzed separately. For example, one studyCitation38 comparing milnacipran with fluoxetine used once-daily dosing for both of the antidepressants. In view of the half-life of milnacipran (7–8 hours) this protocol was inappropriate given that twice daily dosing of milnacipran is recommended. In two studies,Citation39,Citation40 each comparing two doses of milnacipran with a single dose of a SSRI, the meta-analysis inappropriately compared each dose of milnacipran with the SSRI, using the single SSRI group twice, thus giving excessive importance to the SSRI groups. Most importantly, however, the analysis combined, without distinction, data from a study in severely depressed hospitalized patientsCitation33 (baseline HDRS > 32) with data from studies in mildly depressed outpatientsCitation32,Citation41 (baseline HDRS < 24).

Another analysis of studies comparing milnacipran with SSRIsCitation42 concluded that, on the basis of all available evidence, milnacipran, like duloxetine and mirtazapine, had “probable superior efficacy” compared with SSRIs.

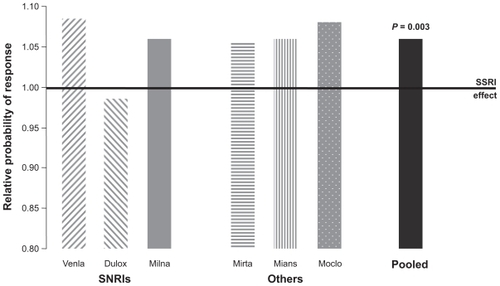

Comparison of milnacipran with other SNRIs

With the exception of the study described in this supplementCitation43 which showed equivalent efficacy of milnacipran and venlafaxine at high doses, no studies comparing milnacipran with other SNRIs have been carried out. However, all three SNRIs have been compared with SSRIs, and comparisons of venlafaxine with SSRIs and milnacipran with SSRIs have been subjected to meta-analyses which have been juxtaposed for comparison.Citation11 A similar level of efficacy for the SSRIs was seen across all of the studies. Milnacipran, as well as venlafaxine, produced remission rates about 10% higher than those of the SSRIs.Citation11 More recently a meta-analysis of 93 trials comparing a dual-action antide-pressant (venlafaxine, milnacipran, duloxetine, mirtazapine, mianserin, or moclobemide) with one or more SSRIs has been published.Citation44 This analysis, involving over 17,000 patients, confirms the overall superiority of the dual-action antidepressants compared with the SSRIs (). In addition, this meta-analysis shows a similar level of efficacy for all of the dual-action antidepressants, with the exception of duloxetine which, in this analysis, was less effective than the other dual-acting agents. Thus, it would seem reasonable to conclude that there is a comparable level of antidepressant efficacy for milnacipran and venlafaxine and probably duloxetine, although further data is required for the latter.

Figure 4 Meta-analysis of 93 studies comparing dual action antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsinvolving 17,036 patients.Citation37 Columns show the relative probability of response compared with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Figure drawn from data in Papakostas et al.Citation44

Similarly, in the absence of direct comparative studies between the SNRIs it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions on comparative tolerability. However, in the various studies comparing an SNRI with SSRIs, the side effect profiles of all three SNRIs show qualitative differences in comparison with those of the SSRIs. The most common adverse effects with the SSRIs are nausea, vertigo/dizziness, dry mouth, and insomnia. Only dry mouth appears to be systematically more common with SNRIs than with SSRIs. The dry mouth experienced with SNRIs is of noradrenergic origin and is analogous to that encountered during stress. The overall frequency of adverse events with milnacipran appears to be less than for venlafaxine and duloxetine.Citation11 However, direct head-to-head comparisons are needed before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

Fatalities have been reported due to overdose of venlafaxine alone or in combination with other compounds,Citation45,Citation46 often following serotonin syndrome. Fatal toxicity index (deaths caused by a drug/million prescriptions) is a very crude measure of drug toxicity and should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, fatal toxicity studies from England, Scotland, and Wales have provided some interesting data. Deaths due to acute poisoning by a single antidepressant have been compiled for the period 1993–1999.Citation47 While the SSRIs caused between 1–3 deaths/million prescriptions, venlafaxine had an index of over 13 deaths/million prescriptions. A subsequent analysis for the period 1998–2000 found similar results (1–3 and 13 deaths/million prescriptions, for SSRIs and venlafaxine, respectively).Citation48

Milnacipran appears not to cause any particular concern in overdose. Patients have absorbed up to 2.8 g (one month’s supply at the recommended dose) without any major effects other than sedation. In particular, no cardiovascular complications have been recorded. No fatalities have been recorded with milnacipran alone.Citation49 At the present time, no cases of lethal overdose with duloxetine have been published.

Efficacy of milnacipran in preventing recurrent depressive episodes

Major depression is generally a recurrent disorder and 75%–80% of patients experience repeated episodes.Citation50 There is also evidence that the risk of recurrence tends to increase with each successive episode.Citation50,Citation51 The role of an efficient antidepressant is therefore not only to get patients well, but to keep them well.

A recurrence prevention study with milnacipran consisted of a six-week open treatment period followed by a continuation phase of 18 weeks for the responders. Patients with a sustained remission at the end of this 24-week period were randomized to continuing treatment with milnacipran or to placebo under double-blind conditions and followed for a further 12 months. There was significantly less recurrence of depressive episodes in milnacipran-treated patients, as determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis of the cumulative probability of recurrence.Citation52 By the end of the 12-month double-blind phase, 16.3% of patients treated with milnacipran had relapsed compared with 23.6% of patients on placebo (P < 0.05). The level of tolerability and safety of milnacipran during this 18-month study was equivalent to that reported in relapse/recurrence prevention studies with SSRIs.Citation53,Citation54

Milnacipran: a unique antidepressant?

Whether or not the profile described above justify referring to milnacipran as a unique antidepressant, it is clear that this agent has a distinct combination of characteristics.

It is the only SNRI with a balanced (1:1) activity on NE and 5-HT reuptake inhibition. Its efficacy in mild, moderate, and severe depression and a good overall tolerability are combined with a low risk of causing pharmacokinetic drug- drug interactions, sexual dysfunction, minimal effects on body weight in normal-weight patients, and a lack of toxicity in overdose. This particular profile qualifies milnacipran as a first-line antidepressant for many depressed patients. Milnacipran may be particularly well-suited for low-energy, slowed-down patients. Patients who have been withdrawn from SSRIs or other antidepressants due to lack of efficacy or intolerance may find milnacipran to be an effective therapeutic option.

Note that this overview highlights what we consider to be the most interesting and relevant points of the profile of milnacipran and does not claim to be exhaustive. Approved indications and safety recommendations may vary between countries, so prescribers should check on the summary of product characteristics in their own country.

Disclosure

Dr Kasper has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmith-Kline, Organon, Sepracor and Servier; has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Bristol- Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Organon, Schwabe, Sepracor, Servier, Janssen, and Novartis; and has served on speakers’ bureaus for AstraZeneca, Eli Lily, Lundbeck, Schwabe, Sepracor, Servier, Pierre Fabre, and Janssen.

References

- BauerMBschorTPfennigAWorld Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders in Primary CareWorld J Biol Psychiatry2007826710417455102

- NuttDJRelationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200869Suppl E14718494537

- GillmanPKTricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updatedBr J Pharmacol2007151673774817471183

- KasperSZoharJSteinDJDecision-Making in PsychopharmacologyLondonMartin Dunitz2002

- KoenigAMThaseMEFirst-line pharmacotherapies for depression – what is the best choicePol Arch Med Wewn200911978478486

- MoretCCharveronMFinbergJPBiochemical profile of midalcipran (F 2207), 1-phenyl-1-diethyl-aminocarbonyl-2-aminomethyl-cyclopropane (Z) hydrochloride, a potential fourth generation antidepressant drugNeuropharmacology198524121112193005901

- MoretCIsaacMBrileyMProblems associated with long-term treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsJ Psychopharmacol20092396797418635702

- ArrollBMacgillivraySOgstonSEfficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: A meta-analysisAnn Fam Med20053544945616189062

- AndersonIMSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: A meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerabilityJ Affect Disord2000581193610760555

- NuttDDemyttenaereKJankaZThe other face of depression, reduced positive affect: The role of catecholamines in causation and cureJ Psychopharmacol200721546147117050654

- StahlSMGradyMMMoretCBrileyMSNRIs: Their pharmacology, clinical efficacy, and tolerability in comparison with other classes of antidepressantsCNS Spectr200510973274716142213

- VaishnaviSNNemeroffCBPlottSJMilnacipran: A comparative analysis of human monoamine uptake and transporter binding affinityBiol Psychiatry200455332032214744476

- MongeauRWeissMde MontignyCBlierPEffect of acute, short-and long-term milnacipran administration on rat locus coeruleus noradrenergic and dorsal raphe serotonergic neuronsNeuropharmacology1998379059189776386

- MuneokaKShirayamaYTakigawaMShiodaSBrain region-specific effects of short-term treatment with duloxetine, venlafaxine, milnacipran and sertraline on monoamine metabolism in ratsNeurochem Res20093454255518751896

- PuozzoCLeonardBEPharmacokinetics of milnacipran in comparison with other antidepressantsInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 415278923123

- Division of Clinical Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Indiana University Schhol of MedicineP450 Drug Interaction Table Available from: http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.aspAccessed on May 25, 2010

- ParisBLOgilvieBWScheinkoenigJAIn vitro inhibition and induction of human liver cytochrome p450 enzymes by milnacipranDrug Metab Dispos200937102045205419608694

- RosenRCLaneRMMenzaMEffects of SSRIs on sexual function: A critical reviewJ Clin Psychopharmacol19991967859934946

- KeltnerNLMcAfeeKMTaylorCLMechanisms and treatments of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunctionPerspect Psychiatr Care20023811111612385082

- ClaytonAHPradkoJFCroftHAPrevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressantsJ Clin Psychiatry20026335736612000211

- RaskinJGoldsteinDJMallinckrodtCHFergusonMBDuloxetine in the long-term treatment of major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2003641237124414658974

- DetkeMJWiltseCGMallinckrodtCHDuloxetine in the acute and long-term treatment of major depressive disorder: A placebo-and paroxetine-controlled trialEur Neuropsychopharmacol20041445747015589385

- BaldwinDMorenoRABrileyMResolution of sexual dysfunction during acute treatment of major depression with milnacipranHum Psychopharmacol200823652753218536065

- MichelsonDFavaMAmsterdamJInterruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trialBr J Psychiatry200017636336810827885

- PinzaniVGiniesERobertLVenlafaxine withdrawal syndrome: Report of six cases and review of the literatureRev Med Interne200021328228410763190

- PerahiaDGKajdaszDKDesaiahDHaddadPMSymptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorderJ Affect Disord2005891320721216169088

- VandelPSechterDWeillerPost-treatment emergent adverse events in depressed patients following treatment with milnacipran and paroxetineHum Psychopharmacol200419858558615570574

- Ness-AbramofRApovianCMDrug-induced weight gainDrugs Today (Barc)20054154755516234878

- Pierre Fabre Médicament – data on file.

- KasperSPletanYSollesATournouxAComparative studies with milnacipran and tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of patients with major depression: A summary of clinical trial resultsInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 435398923125

- Lopez-IborJGuelfiJDPletanYMilnacipran and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressionInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 441468923126

- SechterDVandelPWeillerEA comparative study of milnacipran and paroxetine in outpatients with major depressionJ Affect Disord20048323233236

- ClercGMilnacipran/Fluvoxamine Study GroupAntidepressant efficacy and tolerability of milnacipran, a dual serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor: A comparison with fluvoxamineInt Clin Psychopharmacol2001163145151

- MontesJMFerrandoLSaiz-RuizJRemission in major depression with two antidepressant mechanisms: Results from a naturalistic studyJ Affect Disord2004791322923415023475

- LiGYUekiHYamamotoYYamadaSAssociation between the scores on the general health questionnaire-28 and the saliva levels of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol in normal volunteersBiol Psychol200673220921116472905

- FergusonJMMendelsJSchwartGEEffects of reboxetine on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale factors from randomized, placebo-controlled trials in major depressionInt Clin Psychopharmacol2002172455111890185

- PapakostasGIFavaMA meta-analysis of clinical trials comparing milnacipran, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of major depressive disorderEur Neuropsychopharmacol2007171323616762534

- AnsseauMPapartPTroisfontainesBControlled comparison of milnacipran and fluoxetine in major depressionPsychopharmacology (Berl)199411411311377846195

- AnsseauMvon FrenckellRGérardMAInterest of a loading dose of milnacipran in endogenous depressive inpatients. Comparison with the standard regimen and with fluvoxamineEur Neuropsychopharmacol1991121131211821700

- GuelfiJDAnsseauMCorrubleEA double-blind comparison of the efficacy and safety of milnacipran and fluoxetine in depressed inpatientsInt Clin Psychopharmacol19981331211289690979

- LeeMSHamBJKeeBSComparison of efficacy and safety of milnacipran and fluoxetine in Korean patients with major depressionCurr Med Res Opin20052191369137516197655

- MontgomerySABaldwinDSBlierPWhich antidepressants have demonstrated superior efficacy? A review of the evidenceInt Clin Psychopharmacol200722632332917917550

- MansuyLAntidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxineNeuropsychiatric Disease Treatment2010this supplement

- PapakostasGIThaseMEFavaMAre antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agentsBiol Psychiatry200762111217122717588546

- SettleECJrAntidepressant drugs: Disturbing and potentially dangerous adverse effectsJ Clin Psychiatry199859Suppl 1625309796863

- MazurJEDotyJDKrygielASFatality related to a 30-g venlafaxine overdosePharmacotherapy200323121668167214695048

- BuckleyNAMcManusPRFatal toxicity of serotoninergic and other antidepressant drugs: Analysis of United Kingdom mortality dataBMJ200232573761332133312468481

- CheetaSSchifanoFOyefesoAAntidepressant-related deaths and antidepressant prescriptions in England and Wales, 1998–2000Br J Psychiatry2004184414714702226

- MontgomerySAProstJFSollesABrileyMEfficacy and tolerability of milnacipran: An overviewInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 447518923127

- AngstJCourse of mood disorders: A challenge to psychopharmacologyClin Neuropharmacol199215Suppl 1 Pt A444445

- MajMVeltroFPirozziRPattern of recurrence of illness after recovery from an episode of major depression: A prospective studyAm J Psychiatry199214967958001590496

- RouillonFWarnerBPezousNMilnacipran efficacy in the prevention of recurrent depression: A 12-month placebo-controlled studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol200015313314010870871

- DooganDPCaillardVSertraline in the prevention of depressionBr J Psychiatry19921602172221540762

- MontgomerySADunbarGParoxetine is better than placebo in relapse prevention and the prophylaxis of recurrent depressionInt Clin Psychopharmacol1993831891958263317

- KochSHemrick-LueckeSKThompsonLKComparison of effects of dual transporter inhibitors on monoamine transporters and extracellular levels in ratsNeuropharmacology200345793594414573386

- DeecherDCBeyerCEJohnstonGDesvenlafaxine succinate: A new serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitorJ Pharmacol Exp Ther2006318265766516675639