Abstract

Background

Although there are controversial issues (the “American view” and the “European view”) regarding the construct and definition of agoraphobia (AG), this syndrome is well recognized and it is a burden in the lives of millions of people worldwide. To better clarify the role of drug therapy in AG, the authors summarized and discussed recent evidence on pharmacological treatments, based on clinical trials available from 2000, with the aim of highlighting pharmacotherapies that may improve this complex syndrome.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature regarding the pharmacological treatment of AG was carried out using MEDLINE, EBSCO, and Cochrane databases, with keywords individuated by MeSH research. Only randomized, placebo-controlled studies or comparative clinical trials were included.

Results

After selection, 25 studies were included. All the selected studies included patients with AG associated with panic disorder. Effective compounds included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors, and benzodiazepines. Paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, and clomipramine showed the most consistent results, while fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, and imipramine showed limited efficacy. Preliminary results suggested the potential efficacy of inositol; D-cycloserine showed mixed results for its ability to improve the outcome of exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy. More studies with the latter compounds are needed before drawing definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

No studies have been specifically oriented toward evaluating the effect of drugs on AG; in the available studies, the improvement of AG might have been the consequence of the reduction of panic attacks. Before developing a “true” psychopharmacology of AG it is crucial to clarify its definition. There may be several potential mechanisms involved, including fear-learning processes, balance system dysfunction, high light sensitivity, and impaired visuospatial abilities, but further studies are warranted.

Introduction

Definition

Agoraphobia (AG) is a phobic-anxious syndrome with a long history. The first account is credited to Westphal’s classic 1871 description:

“The anxiety is at its most intense in enclosed spaces [...] (The patient) begins to feel hot, flustered, tremulous, foolish and panic stricken [...] some patients describe fear of developing a panic attack or exhibiting anxiety in the presence of others…”Citation1

Currently the two officially recognized diagnostic manuals used in psychiatric research are the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)Citation2 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10).Citation3 Each manual gives quite a different definition of AG, with only two common features that are clearly present:

Marked distress in or avoidance of characteristic situations such as crowds, public places, and traveling alone and away from home;

Experiencing symptoms of anxiety when confronted with the feared situation.

The most relevant differences in the diagnostic criteria are:

AG is not recognized as an independent disorder in the DSM-IV-TR, while in the ICD-10 it is;

There is an explicit reference to PAs or panic-like symptoms in the DSM-IV-TR, while in ICD-10 there is not (however, the latter requires at least two symptoms of a list fully overlapping with the one defined for PAs in the DSM-IV-TR);

While the ICD-10 clarifies the excessive or unreasonable nature of AG, the DSM-IV-TR does not explicitly state this aspect;

There are no explicit exclusion criteria for specific or social phobia in the ICD-10, whereas these are stated in the DSM-IV-TR.

Given these observations, it is not easy to find a widely accepted definition of AG; moreover, there is a current debate between those who strictly link AG with PAsCitation4–Citation6 and those who view AG as an independent concept.Citation7–Citation9 The authors, well aware of this problem, and aware of the use of the DSM definition in all pharmacological studies referring to AG in some way, will discuss the topic of this review based on the DSM-IV-TR.

AG as viewed in the United States and Europe

Effective therapeutic and pharmacological strategies depend on the choice of a correct target; therefore, discussing current different views of the concept of AG may be relevant for the pharmacological discussion that will follow.

Psychiatrists in the United States, and many others worldwide, consider PAs as the organizing psychopathological phenomena of panic-agoraphobic disease. Unexpected PAs are the “primum movens” that induce a defensive reaction by patients with the development of anticipatory anxiety and AG.Citation4,Citation10 In this view, “true” AG is the direct consequence of PAs, although its severity depends on several aspecific individual factors (eg, temperament) that influence the adaptive reactions of an individual to PAs, as well as to any other threatening condition. On the other hand, many European psychiatrists embrace the idea that agoraphobic attitude precedes the development of PAs and panic disorder (PD); thus, a specific temperament is needed for the development of PD or for the development of AG without previous unexpected PAs. Studies on clinical population strongly support the “American view,” while epidemiological studies on general population seem to support the “European view.” The authors’ impression is that, once again, the main problem is the lack of a clear definition of the concept, and it is probable that these two views refer to qualitatively different concepts. The critical point of difference may be related to the meaning of negative symptoms experienced in agoraphobic environments: the American view considers them as the expression of panic vulnerability, while the European view includes them as part of the physiological anxiety reaction. A detailed discussion of the concept of AG goes beyond the aim of this article, but for more information there are some excellent publications available.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11

If the American view is accepted, pharmacological treatment of AG mainly relies on the blockade of PAs and on the facilitation of the extinction processes. If the European view is accepted, drug treatment of AG should focus on the modification of phobic temperament.

Agoraphobic behaviors and medical illnesses

Another open question is the classification and definition of patients with agoraphobic-like conditions who have concerns regarding incapacitation because of a medical condition, or fear of embarrassment because of unpredictable medical symptoms, but who fail to report panic-like symptoms.

Several medical conditions such as cardiovascular or respiratory diseases are associated with persistent worry about the occurrence of physical symptoms in different situations of daily life, resulting in anticipatory anxiety, which patients try to reduce by avoiding the feared situations or through seeking reassurance.Citation12 In clinical practice, patients with heart failure or dyspnea crises are often afraid of staying in situations where help may not be available or where they have experienced clinical symptoms. This may in turn lead to heightened physiological arousal, to a more intense and generalized perception of physical signals, with catastrophic interpretations of harmless body sensations, resulting in anxiety symptoms and avoidant behaviors. Functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndromeCitation13 are associated with severe AG in patients with PD, but they may also induce avoidant behaviors without the co-occurrence of PD. Despite their potential clinical relevance, these agoraphobic-like conditions are often underestimated in clinical settings; the patients seek help mainly for physical symptoms, often not drawing attention to their phobic avoidance; and psychiatrists or psychologists rarely get to treat them. Consequently, research studies on these conditions – investigating potential pathogenetic mechanisms, relationships with other phobic syndromes, and treatment strategies – are lacking.

Putative mechanisms underlying the development of agoraphobic behaviors

Fear conditioning and emotional learning in AG

Several studies have investigated the neurobiology of PAs, PD, and PD with AG, whereas AG either as a syndrome or as a distinct disorder has rarely been studied. Given the mentioned difficulties in defining AG, even data available using DSM criteria suggest that the pathophysiology of AG is not well understood and the brain areas associated with this condition have not yet been consistently identified. Moreover, no longitudinal studies are available in high-risk samples; thus, it is difficult to understand if abnormalities found are the consequence of the disorder or if they perhaps play an etiopathogenetic role.

Fear conditioning and emotional-learning processes are implicated in AG. Exposure to recurrent unexpected PAs may cause conditioning of fear to exteroceptive and interoceptive cues present during PAs, with the development of defensive behaviors leading to agoraphobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety. Over time, via learning mechanisms of stimulus generalization, fear conditioning may extend to a range of stimuli resembling the original conditioned stimuli co-occurring with panic, worsening avoidance behaviors, and anxious anticipation of panic (the American view). Alternatively, agoraphobics may have a hypersensitive fear-conditioning system that may facilitate triggering of PAs (the European view).

Unfortunately, all studies are based on the American view. Recent studies applying experimental conditioning paradigms found patients with PD, compared with healthy controls, had an enhanced resistance to extinction learning of aversive conditioned responses,Citation14 a stronger proclivity toward fear-conditioned overgeneralization,Citation15 and elevated fear responding to learned safety cues with slower acquisition in safety learning.Citation16 Although these studies were not specifically focused on comparisons between patients with or without AG, their results support the idea that fear-learning processes and compromised capacity for inhibiting fear responses in safe contexts may be implicated in phobic avoidance in PD.Citation17 Finally, a blunted fear-potentiated startle response to imagery of PA situations was observed in patients with PD and the most severe AG, compared with patients without or with only moderate AG, suggesting a compromised underlying fear-defense brain circuitry in the condition of chronic hyperarousal related to broad conditioned avoidance and high anticipatory anxiety.Citation18 It is not clear if these findings are the consequence of the disorder or if they precede it, since no longitudinal high-risk studies are available.

Neuroanatomical studies support the role of emotional learning processes in the development of fear responses. Indeed, this processes a highly complex mechanism that mainly involves the amygdala, with its projections to brain regions mediating the autonomic, endocrine, and behavioral components of the fear responses, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, exerting an inhibitory modulation on amygdala activation; however, it also implicates multiple interconnected neural pathways modulating attention, appraisal, safety/threat discrimination, and emotion regulation processes that interact with fear learning to influence the fear response.Citation17,Citation19–Citation22

These pathways also seem to be involved in AG. In a recent single pilot functional magnetic resonance imaging study by Wittmann et al,Citation20 researchers investigated neural mechanisms of AG and anticipatory anxiety in a small sample of patients with PD and AG using AG-specific stimuli (ie, pictures of agoraphobic situations). The study showed a significant activation in the parahippocampal cortex, the precuneus, and the insula during presentation of the AG-specific pictures, suggesting an involvement of higher spatial and visual processing, activation of autobiographical memory and self-referential aspects, and monitoring of internal physical sensations during induced agoraphobic anxiety; in addition, an increased activation of the amygdala and the inferior frontal cortex/insula in anxious anticipation of agoraphobic stimuli was found. Although this study is preliminary and control groups are missing, these findings support a potential connection between agoraphobic anxiety and the activations of several brain areas involved in perceptual and fear-learning processes.

Given the role of the mentioned brain structures in the modulation of agoraphobic behaviors, manipulating neurotransmitters’ systems that are involved in their activation and de-activation could play a part in the treatment of AG. The serotonergic system may have an inhibitory action on the locus coeruleus and amygdala, it may reduce the hypothalamic release of corticotrophin-releasing factor, and it may inhibit one-way escape in the midbrain periaqueductal gray,Citation23 thus modulating behavioral and physiological responses to fear or stressful stimuli. The noradrenergic system seems to modulate autonomic arousal and behavioral activation in response to threatening stimuli and stressful situations, while the release of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions may be involved in fear-conditioning processes and in the acquisition of conditioned fear behaviors in animal models.Citation24 Consolidation of fear memory and fear extinction appear to be modulated by activity of the glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in the amygdala and limbic regions.Citation21 Accordingly, antagonists of NMDARs impair fear acquisition and extinction if administered shortly before a conditioning session or after extinction training;Citation25 the partial NMDAR agonist D-cycloserine (DCS), a novel compound that has been investigated in AG with PD, may facilitate fear extinction during exposure therapy either by enhancing NMDAR function during extinction or by reducing NMDAR function during consolidation of fear memory.Citation26 Finally, the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system may inhibit neuronal activation and excessive output within limbic structures and fear circuits, facilitating fear extinction.Citation27

Balance, visuospatial systems, and AG

In the last years, several studies in patients with PD and AG found subclinical abnormalities of their balance system function that seem to influence the severity of AG and may contribute to their symptoms of dizziness and discomfort in complex sensorial environments (eg, shopping malls, traffic, crowds).Citation28,Citation29 The balance control of many patients with PD and AG appears to rely mainly on nonvestibular, proprioceptive, or mostly visual (visual dependence) cues;Citation30 recent preliminary results from the authors’ team showed a higher balance system reactivity to peripheral visual stimulation in patients with PD and AG, possibly linked to a more active “visual alarm system”, involving visual, vestibular, and limbic areas, that may influence the development of AG in situations where environmental stimuli are uncertain. Citation31 Overall, a “balance vulnerability” to AG may exist, and small postural modifications or sensorial stimuli from the surrounding environment may play a part in triggering situational anxiety/panic. Similarly, patients with phobic postural vertigo, a syndrome characterized by dizziness and autonomic/anxiety responses in standing or walking without specific vestibular diseases, often show AG-like behaviours,Citation32 suggesting that high sensitivity to environmental conditions may also lead to phobic avoidance without PD.

Finally, patients with AG and PD showed visuospatial cognition biases, with scarce ability of spatial orientation and spatial navigation and visual memory deficits, possibly related to distortion of the representational mechanism of extrapersonal space;Citation33 it has been proposed that an over-projection of the representation of the near space immediately surrounding the body (peripersonal space) has a role in claustrophobic fear.Citation34

Patients with PD and AG also showed high sensitivity to environmental light or bright stimuli, having photophobic behavior,Citation35 abnormal retinal light responses, and pupillary reflex dysfunctions, possibly linked to serotonergic and/or dopaminergic function.Citation36 Moreover, since a relationship between photosensitivity and migraine exists,Citation37 and a high comorbidity of PD with AG and migraine was found,Citation38 a broader dysfunction of autonomic and/or serotonergic systems may link photosensitivity, migraine, PAs, and AG.Citation39 Overall, the findings of high sensitivity of patients with PD and AG to several stimuli in the surrounding environment support the idea that agoraphobic conditions may involve the activation of complex systems, beyond the simple fear of the recurrence of PAs, including emotional responses to destabilizing/unpleasant environmental situations and operant-learning processes related to the avoidance of physical experiences provoking discomfort in everyday life.

Treatments for AG

Until now, clinical studies, and consequently the current guidelines, have been focused on therapy for AG with PD, whereas studies on AG without PAs are lacking. Both pharmacological treatments with drugs acting on different neurotransmitters and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may be effective in PD with AG. The debate is ongoing as to whether these treatments are equally effective and whether combined treatments provide additional benefits; recently, preliminary evidence has been reported of a better efficacy of combined therapy than antidepressants or psychotherapy alone in acute-phase treatment and some superiority of antidepressants as compared with CBT after 9 months of treatment.Citation40 Overall, the main current guidelines state that at present it is not possible to ascertain which of these treatment modalities is more effective in PD with AG, and specific criteria for choosing medication, CBT, or combined therapy are not available.Citation41 The efficacy of CBT in AG with PD is thought to be explained by an activation and modification of relevant fear-learning processes via habituation and/or extinction and/or examining dysfunctional beliefs; however, 30%–40% of patients do not achieve significant improvement with CBT alone,Citation42 making room for a potential utility of pharmacological interventions for this behavioral condition. Even though the mechanisms of action of the existing drugs with antipanic and antiphobic properties remain unclear, the utility of these drugs may be mediated by their effects on several brain pathways potentially involved in pathophysiology of AG with PD.

Medications acting on neurotransmitters appeared to obtain comparable rates of clinical remission for both PAs and agoraphobic avoidance in patients with PD and AG, while the probability of relapses during long-term pharmacological treatment seems to be lower for AG than for PAs.Citation43 Nevertheless, in a study by van Apeldoorn et al,Citation44 between 20% and 40% of patients with PD and AG did not fully respond to adequate pharmacotherapy alone or, similarly, to CBT administered alone, and so far the combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy does not appear to fill this gap. In addition, 25%–50% of patients relapse within 6 months after drug discontinuation and up to 40%–50% of patients still have residual panic-phobic symptoms after 3–6 years.Citation45 Finally, it is still unclear to what extent the pharmacological remission of both full and limited-symptom spontaneous PAs may indirectly influence the remission of AG in patients with AG and PD, or to what extent a specific drug effect on phobic conditions is necessary to obtain a complete remission.

Aim of the study

Given the relevance of AG to the general population and the tendency of AG to become chronic, looking for effective treatments is important. To reach this goal, the authors will summarize and discuss recent evidence regarding the pharmacological treatment of AG, based on clinical trials available from 2000 to June 2011, discuss factors that might affect the validity of the studies, and, finally, suggest putative mechanisms that may be involved in the development of new drugs.

Methods

A scientific literature search was performed using MEDLINE, EBSCO, and Cochrane databases, with keywords individuated by MeSH research. These keywords included (AG OR “panic disorder”) AND (“drug therapy” OR pharmacotherapy) AND behavior*; NOT (“depressive disorder” OR “mood disorder”); NOT (“psychotic disorder”). The syntax respected instruction information described in the databases. Citation searches were also conducted manually.

All studies were analyzed applying the following inclusion criteria:

English-language articles

Clinical trials

Blinded studies

Studies published after 2000

Studies where psychopathological diagnosis was performed using DSM criteria, ICD-10 criteria, or an exact description of the disorder and duration of symptoms

Clinical outcomes had to be scored by a standardized psychometric scale, by self-report, by observer-rated measures, by behavior test, or by a numeric rating index of anxiety and/or agoraphobic symptoms (eg, avoidance, anticipatory anxiety, and anxiety state)

For the groups in the studies, each drug to be administrated without other drugs that can influence or interact with treatment. For the selection of articles, exclusion criteria were:

Trials not randomized controlled and without control group

Case reports

Studies where population’s diagnosis was PD without AG

Studies where AG was in comorbidity with other psychopathologies or neurological pathologies

Studies with a pediatric population.

After selection, articles were divided on the basis of the pharmacological classes. After this subdivision, in each article the following parameters were identified and described: (1) characteristics of the studies; (2) drug therapies and doses; (3) duration of treatments; (4) control group(s); (5) outcome measures of agoraphobic symptoms and/or panic/anxiety; (6) timing of follow-up; and (7) results. When available, specific psychometric measures of AG were reported and highlighted; when these were lacking, global scores of psychometric scales that include evaluation of AG severity, such as the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale, the Panic Attack Symptoms Scale, or the Panic Disorder Severity Scale, were reported.

Results

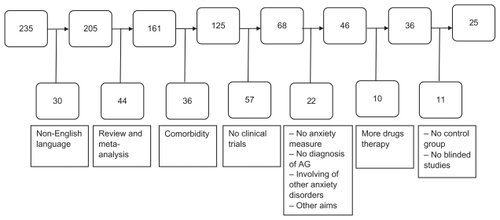

The electronic search identified 235 articles. Among these, 210 were excluded and 25 studies were selected (). No studies were found that focused on AG without PD, and all the selected studies included patients with AG and PD. Pharmacological classes used in the selected clinical trials are summarized in . Details of the selected studies are outlined in .

Table 1 Number of articles selected for each pharmacological class

Table 2 Systematic analysis of selected studies

Discussion

This review of randomized, controlled pharmacological trials on AG published over the last 11 years underscores the difficulties in identifying psychotropic drugs that may specifically improve AG. Many reasons may explain these difficulties. Since the few studies that included patients with AG and panic-like symptoms (but without full-blown PD) had many methodological shortcomings (eg, lack of randomization or control groups), they were excluded from this review; therefore, no specific data on “not panic” agoraphobics are available. All the studies reported in this article included patients with AG associated with PD, as per DSM criteria, and so disentangling the specific effects of AG is difficult.

The authors begin by discussing the putative limitations of the studies included. Many studies on PD with AG reported outcome measures evaluating only the global improvement of the clinical condition, without highlighting potential differences in drug effects on distinct clinical phenomena such as frequency of PAs, anticipatory anxiety, phobic avoidance, and their interaction. Moreover, some methodological issues may influence the results of the included studies. Several studies did not report effect size analysis in their results, thus decreasing the strength of their conclusions. The sample sizes were often small and some studies included patients with other psychiatric disorders in comorbidity with PD and AG, thus possibly affecting the external validity of the results and/or masking potential significant effects of the treatments. Some data arose from pharmaceutical studies that might have had different settings than spontaneous clinical studies, thus affecting the comparisons of the results. In a few comparative clinical trials, the placebo group was missing,Citation48,Citation52,Citation57,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63,Citation68 even though the comparator drugs were well-known, effective antipanic drugs. Two studiesCitation60,Citation62 were single-blinded (eg, the investigator rating psychometric scales did not know which treatment was administered, whereas the patients did), thus patients’ expectance of treatment efficacy cannot be excluded as an influence. Finally, all studies but twoCitation44,Citation45 considered short-term outcomes, not allowing for conclusions regarding maintenance properties and long-term effects of the tested drugs.

Keeping these limitations in mind, the authors found that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are the most studied drugs in AG with PD, according to previous reviews.Citation12,Citation23 Among SSRIs, paroxetine is the most used drug in the selected clinical trials,Citation48,Citation54–Citation57,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63 showing high efficacy on both panic and phobic symptoms, and also when severity of AG is measured by specific psychometric scales. The comparison between CBT and paroxetine suggests their similar efficacy on agoraphobic behaviors but with some superiority of paroxetine on PAs in the acute phases of the treatment;Citation55 finally, the addition of paroxetine to CBT in patients that did not respond to CBT alone is significantly more effective in improving agoraphobic behaviors than the addition of placebo.Citation54

Overall these data indicate the utility of paroxetine as a pharmacological augmentation strategy in patients with AG who do not fully respond to CBT sessions and they underscore its efficacy on PAs. Since the recurrence of PAs worsen agoraphobic behaviors in PD and interfere with the remission of AG, the efficacy of paroxetine on AG may also be linked to its antipanic properties; thus, treatment with paroxetine in patients with AG and a high recurrence of PAs may be more appropriate than CBT alone. Sertraline,Citation48,Citation57 citalopram,Citation58–Citation60 and escitalopramCitation58,Citation59 also appear to be effective in PD with AG, whereas fluvoxamineCitation48,Citation68 shows less consistent efficacy, at least on PAs and global panic-phobic psychometric measures. Although showing a suppressive effect on spontaneous PAs, fluoxetineCitation53 does not appear to be effective on situational PAs compared with placebo, and its efficacy on AG measures is limited; these findings are similar to those in a study on imipramine performed before 2000,Citation71 supporting the idea that antidepressants may not have a similar effect on all aspects of PD with AG. Among TCAs, which are less tolerable and safe than SSRIs, clomipramine shows an efficacy on both panic and phobic symptoms similar to paroxetine and sertraline,Citation48 whereas imipramine shows mixed results; indeed, although imipramine is more effective than placebo in long-term maintenance,Citation44 it appears to be less effective than sertraline on short-term outcomes,Citation48 as measured by global panic-phobic psychometric scales, and a combined therapy with CBT plus imipramine does not offer significant benefits on agoraphobic symptoms compared with CBT plus placebo.Citation46

Benzodiazepines (BDZs), such as clonazepamCitation50,Citation51 and alprazolamCitation52 are effective in AG with PD and the association of alprazolam to antidepressant in the first weeks of therapy may accelerate the reduction of global anxiety,Citation52 whereas the only study on pagoclone,Citation64 a partial agonist of GABA-A BDZ receptors, shows inconsistent results. However, the use of BDZs is recommended with caution, because of risk of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms;Citation70 moreover, patients receiving combined therapy with CBT and BDZs who subsequently discontinue BDZ treatment experience a loss of efficacy compared with CBT and placebo, possibly due to interference of BDZs with fear-extinction processes.Citation70

Among other pharmacological classes, venlafaxineCitation63 appears to be effective on both panic and phobic symptoms; the only study with inositolCitation68 supports the effectiveness in AG with PD emerging from previous clinical trials,Citation71,Citation72 but more studies are needed before drawing definitive conclusions. ReboxetineCitation61 appears to be effective on both panic and phobic symptoms compared with placebo, while when compared with paroxetineCitation62 it shows a similar efficacy on phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety but a lower efficacy on PAs; these data support the role of the noradrenergic system in modulation of avoidance behaviors but underscore the relevance of acting on the serotonergic system to decrease the PAs. Finally, gabapentinCitation64 does not show different efficacy than placebo and moclobemideCitation49 does not decrease phobic avoidance compared with placebo, even though it does show some efficacy on PAs.

As previously discussed, despite these pharmacological therapeutic options available for PD with AG, they do not seem to be able to achieve a full remission in all treated patients either when administered alone or in association with CBT.Citation67 Beyond the discussed absence of a widely accepted definition, this critical issue may be partly related to the pathogenetic complexity of AG, which is not usually taken into account in clinical trials. A preliminary open study showed that citalopram influences the balance system in patients with PD and AG by improving their postural stability, as measured by static posturography, especially when visual information is lacking; in addition, patients whose posturography scores were highly abnormal at the end of the trial were still agoraphobic, whereas most patients whose balance system function improved were no longer agoraphobic, underscoring the involvement of balance system dysfunction in PD with AG and the relevance of the serotonergic system in connections between balance and AG.Citation73 Further studies are warranted to investigate the possible role of unrecognized balance dysfunctions in patients with PD and AG who do not fully respond to treatments and to study appropriate interventions.

A reanalysis of pooled samples of patients from previous homogeneous pharmacological studies performed by the authors’ team showed a higher efficacy of sertraline and clomipramine than paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram on agoraphobic symptoms (unpublished data). This finding may be related to their additional ability to modulate the dopaminergic system, besides their main effect on the serotonergic system, thus potentially influencing several mechanisms involved in shaping agoraphobic behaviors, such as balance,Citation33 light stimuli sensitivity,Citation35 and conditioning processes;Citation24 however, this idea remains speculative and should be tested in further studies.

Besides well-known antianxiety medications, new emerging drugs are being tested in AG with PD, with the main aim of enhancing the retention of therapeutic learning and fear extinction provided by exposure-based CBT. DCS has improved outcomes from exposure therapy in a virtual reality environment in height-phobic patients.Citation75 DCS has shown mixed results in patients with PD and AG; in a recent study DCS appears to accelerate symptom reduction in more severely ill patients but fails to improve the outcome of CBT in the whole sample of patients with PD and AG.Citation67 This does not confirm previous findings of its additive benefit as an augmentation strategy of CBT on phobic symptoms;Citation66 thus, further studies are warranted. Potential new effective compounds may enhance fear extinction by stimulating the activity of medial prefrontal cortical areas (mPFC), such as methylene blue (MB), which may have an indirect action on mPFC by increasing brain cytochrome oxidase activity, improving oxidative energy metabolism, and thereby supplying the energy needs of synapses involved in consolidation of extinction memory.Citation74 Clinical studies on the efficacy of MB for augmenting exposure-based treatments are currently underway.

The endocannabinoid system is another focus of research investigating new potential therapeutic approaches for anxiety disorders. Indeed, cannabinoid (CB) receptors have been linked to extinction learning in animal models, type 1 CB (CB1) receptors have been found in brain areas related to anxiety and emotional learning (such as the amygdala and hippocampus),Citation76 and CB1 antagonists lead to significant deficits in extinction learning,Citation77 suggesting that CB receptor modulators may improve efficacy of exposure-based psychotherapies in phobic syndromes;Citation78 however, data are not available on PD with AG. Cortisol has been also proposed as an augmentation strategy of extinction consolidation. Human and animal studies showed that acute increases of glucocorticoids can enhance emotional consolidation and extinction-based learning,Citation79 the cortisol administration before virtual exposure to an acrophobic situation appeared to obtain a significantly greater fear reduction post treatment than placebo,Citation80 and preliminary findings showed that the patients with PD and AG having least cortisol release during CBT exposures profited least from therapy.Citation81 Finally, animal studies suggested that compounds with anticholinergic properties, acting in the primary sensory cortex, may improve sensory discrimination of the conditioned danger cue and its approximations; thus, a potential utility of these drugs on the fear-conditioned overgeneralization found in patients with PD has been proposed.Citation15 Till now, no data have been available to evaluate the usefulness of these potential new compounds on AG and so future studies are needed.

Conclusion

Overall, there are several challenging issues in the pharmacological treatment of AG. First of all, a more stable and accepted psychopathological definition of AG is crucial to improve the search for specific treatments. Further neurobiological, functional imaging, and clinical studies are warranted to better understand the pathogenesis of AG, either as a syndrome or as a distinct disorder, and, consequently, to better clarify the mechanisms of action and the usefulness of drugs. In PD with AG the clinical phenomena of phobic avoidance may not be simply related to spontaneous PAs; thus, potential specific effects of compounds on AG should be better tested, as well as new drugs that may have a specific efficacy, such as DCS. Finally, in clinical trials, patients with PD and AG are considered as a homogeneous group, without considering that different symptomatological profiles may exist, possibly reflecting multiple pathogenetic mechanisms involved in shaping agoraphobic behaviors.

In conclusion, there are too many critical issues around both the clinical definition of AG and the pharmacological studies available to give a clear answer regarding the best drug choice for the treatment of AG. Much more research is needed before a specific psychopharmacology of AG can be discussed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MarksIMThe Agoraphobic Syndrome (Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia)Fears, Phobia and RitualNew YorkOxford University Press1987323361

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental DisordersFourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)Washington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- World Health OrganizationICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems10th edArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatry Publishing1992

- KleinDFKleinHMThe utility of the panic disorder conceptEur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci19892385–62682792670574

- BreierACharneyDSHeningerGRAgoraphobia with panic attacks: development, diagnostic stability, and course of illnessArch Gen Psychiatry19864311102910363767595

- NoyesRThe natural history of anxiety disordersRothMNoyesRJrBarrowsGDHandbook of Anxiety: Biological, Clinical and Cultural Perspective1Amsterdam, The NetherlandsElsevier Science Publishers1988115133

- WittchenHUNoconABeesdoKAgoraphobia and panic: prospective-longitudinal relations suggest a rethinking of diagnostic conceptsPsychother Psychosom200877314715718277061

- FavaGARafanelliCTossaniEGrandiSAgoraphobia is a disease: a tribute to Sir Martin RothPsychother Psychosom200877313313818277059

- FaravelliCCosciFRotellaFFaravelliLCatena Dell’ossoMAgoraphobia between panic and phobias: clinical epidemiology from the Sesto Fiorentino StudyCompr Psychiatry200849328328718396188

- PernaGUnderstanding anxiety disorders: from psychology to psychopathology of defense mechanisms from threatRiv Psichiatr2011In press

- WittchenHUGlosterATBeesdo-BaumKFavaGACraskeMGAgoraphobia: a review of the diagnostic classificatory position and criteriaDepress Anxiety201027211313320143426

- PerugiGFrareFToniCDiagnosis and treatment of agoraphobia with panic disorderCNS Drugs200721974176417696574

- SugayaNKaiyaHKumanoHNomuraSRelationship between sub-types of irritable bowel syndrome and severity of symptoms associated with panic disorderScand J Gastroenterol200843667568118569984

- MichaelTBlechertJVriendsNMargrafJWilhelmFHFear conditioning in panic disorder: enhanced resistance to extinctionJ Abnorm Psychol2007116361261717696717

- LissekSRabinSHellerREOvergeneralization of conditioned fear as a pathogenic marker of panic disorderAm J Psychiatry20101671475519917595

- LissekSRabinSJMcDowellDJImpaired discriminative fear-conditioning resulting from elevated fear responding to learned safety cues among individuals with panic disorderBehav Res Ther200947211111819027893

- BrittonJCLissekSGrillonCNorcrossMAPineDSDevelopment of anxiety: the role of threat appraisal and fear learningDepress Anxiety201128151720734364

- McTeagueLMLangPJLaplanteMCBradleyMMAversive imagery in panic disorder: agoraphobia severity, comorbidity, and defensive physiologyBiol Psychiatry201170541542421550590

- ZanoveliJMFerreira-NettoCBrandãoMLConditioned place aversion organized in the dorsal periaqueductal gray recruits the laterodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and the basolateral amygdalaExp Neurol2007208112713617900567

- WittmannASchlagenhaufFJohnTA new paradigm (Westphal-Paradigm) to study the neural correlates of panic disorder with agoraphobiaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2011261318519421113608

- CritchleyHDThe human cortex responds to an interoceptive challengeProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2004101176333633415096592

- JohnstoneTvan ReekumCMUrryHLKalinNHDavidsonRJFailure to regulate: counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depressionJ Neurosci200727338877888417699669

- PasquiniMBerardelliIAnxiety levels and related pharmacological drug treatment: a memorandum for the third millenniumAnn Ist Super Sanita200945219320419636172

- GormanJMKentJMSullivanGMCoplanJDNeuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisedAm J Psychiatry2000157449350510739407

- MyersKMDavisMMechanisms of fear extinctionMol Psychiatry200712212015017160066

- VervlietBLearning and memory in conditioned fear extinction: effects of D-cycloserineActa Psychol (Amst)2008127360161317707326

- LuftTPereiraGSCammarotaMIzquierdoIDifferent time course for the memory facilitating effect of bicuculline in hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and posterior parietal cortex of ratsNeurobiol Learn Mem2004821525615183170

- PernaGDarioACaldirolaDStefaniaBCesaraniABellodiLPanic disorder: the role of the balance systemJ Psychiatr Res200135527928611591430

- StaabJPChronic dizziness: the interface between psychiatry and neuro-otologyCurr Opin Neurol2006191414816415676

- RedfernMSFurmanJMJacobRGVisually induced postural sway in anxiety disordersJ Anxiety Disord200721570471617045776

- CaldirolaDTeggiRBondiSIs there a hypersensitive visual alarm system in panic disorder?Psychiatry Res2011187338739121477868

- BrandtTPhobic postural vertigoNeurology1996466151515198649539

- LöscherWAbnormal circling behavior in rat mutants and its relevance to model specific brain dysfunctionsNeurosci Biobehav Rev2010341314919607857

- LourencoSFLongoMRPathmanTNear space and its relation to claustrophobic fearCognition2011119344845321396630

- KellnerMWiedemannKZihlJIllumination perception in photophobic patients suffering from panic disorder with agoraphobiaActa Psychiatr Scand199796172749259228

- CastrogiovanniPPieracciniFIapichinoSElectroretinogram B-wave amplitude in panic disorderCNS Spectr20016321021316951655

- PurdyRAThe role of the visual system in migraine: an updateNeurol Sci201132Suppl 1S89S9321533721

- YamadaKMoriwakiKOisoHIshigookaJHigh prevalence of comorbidity of migraine in outpatients with panic disorder and effectiveness of psychopharmacotherapy for both disorders: a retrospective open label studyPsychiatry Res20111851–214514820546930

- TeggiRCaldirolaDColomboBDizziness, migrainous vertigo and psychiatric disordersJ Laryngol Otol2010124328529019954562

- Van ApeldoornFJTimmermanMEMerschPPA randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or both combined for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: treatment results through 1-year follow-upJ Clin Psychiatry201071557458620492852

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: management in primary, secondary and community careNICE clinical guideline11312011 Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13314/52599/52599.pdfAccessed on September 15, 2011

- Van ApeldoornFJvan HoutWJMerschPPIs a combined therapy more effective than either CBT or SSRI alone? Results of a multicenter trial on panic disorder with or without agoraphobiaActa Psychiatr Scand2008117426027018307586

- ToniCPerugiGFrareFMataBAkiskalHSSpontaneous treatment discontinuation in panic disorder patients treated with antidepressantsActa Psychiatr Scand2004110213013715233713

- MavissakalianMRPerelJM2nd year maintenance and discontinuation of imipramine in panic disorder with agoraphobiaAnn Clin Psychiatry2001132636711534926

- MavissakalianMRPerelJMDuration of imipramine therapy and relapse in panic disorder with agoraphobiaJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222329429912006900

- MarchandACoutuMFDupuisGTreatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia: randomized placebo-controlled trial of four psychosocial treatments combined with imipramine or placeboCogn Behav Ther200837314615918608313

- BandelowBBroocksAPekrunGThe use of the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (P&A) in a controlled clinical trialPharmacopsychiatry200033517418111071019

- PernaGBertaniACaldirolaDGabrieleACocchiSBellodiLAntipanic drug modulation of 35% CO2 hyperreactivity and short-term treatment outcomeJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222330030812006901

- UhlenhuthEHWarnerTDMatuzasWInteractive model of therapeutic response in panic disorder: moclobemide, a case in pointJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222327528412006898

- ValençaAMNardiAENascimentoIMezzasalmaMALopesFLZinWDouble-blind clonazepam vs placebo in panic disorder treatmentArq Neuropsiquiatr20005841025102911105068

- ValençaAMNardiAEMezzasalmaMATherapeutic response to benzodiazepine in panic disorder subtypesSao Paulo Med J20031212778012870055

- KatzelnickDJSaidiJVanelliMRJeffersonJWHarperJMMcCraryKETime to response in panic disorder in a naturalistic setting: combination therapy with alprazolam orally disintegrating tablets and serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared to serotonin reuptake inhibitors alonePsychiatry (Edgmont)2006312394920877555

- UhlenhuthEHMatuzasWWarnerTDPaineSLydiardRBPollackMHDo antidepressants selectively suppress spontaneous (unexpected) panic attacks? A replicationJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020662262711106133

- KampmanMKeijsersGPHoogduinCAHendriksGJA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy aloneJ Clin Psychiatry200263977277712363116

- HendriksGJKeijsersGPKampmanMA randomized controlled study of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life panic disorderActa Psychiatr Scand20101221111919958308

- WedekindDBroocksAWeissNEngelKNeubertKBandelowBA randomized, controlled trial of aerobic exercise in combination with paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorderWorld J Biol Psychiatry201011790491320602575

- BandelowBBehnkeKLenoirSSertraline versus paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: an acute, double-blind noninferiority comparisonJ Clin Psychiatry200465340541315096081

- StahlSMGergelILiDEscitalopram in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry200364111322132714658946

- BandelowBSteinDJDolbergOTAndersenHFBaldwinDSImprovement of quality of life in panic disorder with escitalopram, citalopram, or placeboPharmacopsychiatry200740415215617694478

- PernaGBertaniACaldirolaDSmeraldiEBellodiLA comparison of citalopram and paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomized, single-blind studyPharmacopsychiatry2001343859011434404

- VersianiMCassanoGPerugiGReboxetine, a selective norepi-nephrine reuptake inhibitor, is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for panic disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2002631313711838623

- BertaniAPernaGMigliareseGComparison of the treatment with paroxetine and reboxetine in panic disorder: a randomized, single-blind studyPharmacopsychiatry200437520621015359375

- PollackMHLepolaUKoponenHA double-blind study of the efficacy of venlafaxine extended-release, paroxetine, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorderDepress Anxiety200724111416894619

- PandeACPollackMHCrockattJPlacebo-controlled study of gabapentin treatment of panic disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020446747110917408

- SandfordJJForshallSBellCCrossover trial of pagoclone and placebo in patients with DSM-IV panic disorderJ Psychopharmacol200115320520811565630

- OttoMWTolinDFSimonNMEfficacy of D-cycloserine for enhancing response to cognitive-behavior therapy for panic disorderBiol Psychiatry201067436537019811776

- SiegmundAGolfelsFFinckCD-cycloserine does not improve but might slightly speed up the outcome of in-vivo exposure therapy in patients with severe agoraphobia and panic disorder in a randomized double blind clinical trialJ Psychiatr Res20114581042104721377691

- PalatnikAFrolovKFuxMBenjaminJDouble-blind, controlled, crossover trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200121333533911386498

- MitteKA meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and pharmacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobiaJ Affect Disord2005881274516005982

- OttoMWBruceSEDeckersbachTBenzodiazepine use, cognitive impairment, and cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: issues in the treatment of a patient in needJ Clin Psychiatry200566Suppl 2343815762818

- LevineJControlled trials of inositol in psychiatryEur Neuropsychopharmacol1997721471559169302

- BenjaminJLevineJFuxMAvivALevyDBelmakerRHDouble- blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of inositol treatment for panic disorderAm J Psychiatry19951527108410867793450

- PernaGAlpiniDCaldirolaDRaponiGCesaraniABellodiLSerotonergic modulation of the balance system in panic disorder: an open studyDepress Anxiety200317210110612621600

- KaplanGBMooreKAThe use of cognitive enhancers in animal models of fear extinctionPharmacol Biochem Behav201199221722821256147

- ResslerKJRothbaumBOTannenbaumLCognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fearArch Gen Psychiatry200461111136114415520361

- MoreiraFALutzBThe endocannabinoid system: emotion, learning and addictionAddict Biol200813219621218422832

- HernandezGCheerJFExtinction learning of rewards in the rat: is there a role for CB1 receptors?Psychopharmacology (Berl)2011217218919721519986

- ChhatwalJPDavisMMaguschakKAResslerKJEnhancing cannabinoid neurotransmission augments the extinction of conditioned fearNeuropsychopharmacology200530351652415637635

- OttoMWMcHughRKKantakKMCombined pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: medication effects, glucocorticoids, and attenuated outcomesClin Psychol Sci Prac201017291103

- de QuervainDJBentzDMichaelTGlucocorticoids enhance extinction-based psychotherapyProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2011108166621662521444799

- SiegmundAKösterLMevesAMPlagJStoyMStröhleAStress hormones during flooding therapy and their relationship to therapy outcome in patients with panic disorder and agoraphobiaJ Psychiatr Res201145333934620673917