Abstract

Objective

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with inadequate response to antidepressant treatment (ADT) may suffer a prolonged loss of functioning. This review aimed to determine if self-rated functional measures are informative in randomized placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive therapy in patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT.

Methods

This was a systematic literature review of articles in any language from the MEDLINE database published between January 1990 and March 2017. Eligible studies met the following criteria: patients with MDD; inadequate response to at least one ADT; adjunctive therapy (pharmacological or otherwise) to ADT; placebo control group; randomized controlled trial or a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial; reported a self-rated functioning scale. Study characteristics and functioning efficacy data were extracted.

Results

A total of 2,090 discrete records were screened, 293 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 26 studies were included. All studies were acute (6–12 weeks) except for one 52-week study. The only self-rated functioning scale used in the included studies was the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Of the 13 adjunctive agents identified, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, edivoxetine, and risperidone improved functioning versus placebo (p<0.05), as measured by the SDS total or mean score. On the SDS “work/studies” item, only aripiprazole had a statistically significant benefit, in one study out of four. Thus, where a benefit was observed on the SDS total or mean, this was generally driven by improvement on the “social life” and “family life” items. A limitation of the review is that it only considered published literature from one database.

Conclusion

The SDS, a self-rated functional measure, is informative in acute randomized placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive therapy in patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT. However, the item that measures work performance may be less relevant to this population than the items that measure social and family life.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by symptoms including depressed mood and a loss of interest or pleasure in activities.Citation1 As a consequence of depressive symptoms, patients with MDD typically have impaired functioning across multiple domains, including work, social, and family functioning.Citation2,Citation3 For example, depressive symptoms are associated with reduced marital quality, reduced work performance, and lower earnings.Citation2

Key goals for patients with MDD experiencing a depressive episode are remission and full recovery.Citation4,Citation5 Recovery should be considered in broad terms, encompassing work, social, and family functioning as well as improvement of depressive symptoms.Citation6,Citation7 Indeed, patients with MDD consider a return to normal levels of functioning as one of the most important factors in defining remission from depression.Citation8 Although numerous standardized assessments are available to monitor functioning outcomes in the clinic and in research, functioning scales are used less frequently and less consistently than symptom severity scales.Citation9 Furthermore, functioning may be less responsive to treatment than symptoms, meaning that functional improvement can lag behind symptomatic outcomes.Citation10,Citation11

Despite being the mainstay of pharmacological treatment for MDD, more than half of patients do not respond to antidepressant treatment (ADT), as shown by the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study.Citation12 Patients with inadequate response to ADT have a prolonged loss of functioning and a lower likelihood of employment than those patients who do respond.Citation13,Citation14 Treatment strategies for patients with inadequate response to an optimized dose of ADT include switching to another antidepressant, combining the initial antidepressant with a second antidepressant that has a different mode of action, or augmenting the antidepressant with a non-antidepressant drug.Citation4,Citation15–Citation18 Of the various options for augmentation, second-generation antipsychotics are best supported by the evidence.Citation19 However, the effects of different adjunctive therapies on patient functioning have not been consistently studied, and it is not clear whether existing measures of functioning are useful among patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT.

A recent systematic review investigated the effect of ADT (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, other antidepressants, and psychotherapies such as cognitive behavior therapy [CBT]) on functional outcomes in MDD.Citation20 The review, which excluded clinical studies of adjunctive pharmacotherapies, concluded that functioning improves together with depressive symptoms, but that functional deficits often remain, even among patients who achieve symptomatic remission.Citation20 Given the importance of functioning to the overall well-being of patients, the aim of the present systematic literature review was to determine if self-rated functional measures are informative in randomized placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive therapy in patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT.

Methods

This systematic review adheres to PRISMA.Citation21

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they were published, randomized, placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive therapy to ADT in patients with MDD and inadequate response to at least one ADT, and reported a self-rated scale of functioning. The literature search was performed on 8 March 2017. Reports were limited to those published on or after 1 January 1990. No language exclusions were applied.

Search strategy

The aim of the initial top-level search strategy was to identify studies that satisfied three criteria: 1) the study included patients with MDD; 2) the study was of antidepressant augmentation (with any pharmacological or non-pharmacological approach, such as CBT or deep brain stimulation); and 3) the study included a placebo or sham control group. The US National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database was searched, via PubMed, using the terms: (depress* OR MDD) AND (adjunct* OR “add-on” OR augment* OR resist* OR refractory OR inadequate OR incomplete OR suboptimal) AND (placebo).

Following the initial search it became apparent that these terms were likely to miss some publications of olanzapine–fluoxetine combination (OFC) studies. OFC is indicated for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression in the US,Citation22 and, due to its availability as a single tablet, has been tested against fluoxetine with no need for placebo. Consequently, a second search was performed on 21 March 2017 to capture OFC studies, using the terms: (depress* OR MDD) AND ((olanzapine AND fluoxetine) OR OFC).

Study selection

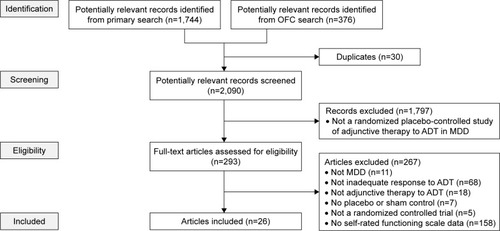

Following the top-level database searches, duplicates were excluded and records were screened to exclude unsuitable articles based on titles and abstracts (). At this stage, studies were not excluded based on a lack of functioning outcomes, because these are often secondary outcomes not mentioned in abstracts.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of published articles examined for inclusion in a systematic review.

After screening, full-text articles for the remaining records were assessed for eligibility, defined as meeting all of the following criteria: 1) the study included patients with MDD; 2) the patients had inadequate response (by any definition) to at least one ADT; 3) the study investigated an adjunctive therapy to ADT; 4) the study included a placebo or sham control group (or a fluoxetine control group, for OFC); 5) the study was a randomized controlled trial or a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial; and 6) the study reported self-rated functioning scale (or subscale) outcomes. Any self-rated functioning scale was eligible, defined as a scale that reflects the user’s actual behavior in the world and is assessed in ways that emphasize doing, performing, maintaining, etc (this is distinct from quality of life – a measure based on self-perception and context with an emphasis on satisfaction, contentment, or enjoyment in various aspects of life).Citation9 Eligibility assessment was performed in duplicate by two reviewers (split between CPW, CE and JARM), and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted for each study, where available: 1) the definition of inadequate response to ADT, both historical (prior to study enrollment) and prospective/ongoing (during the study); 2) the adjunctive treatment (type, dose, and duration); 3) the number of randomized patients; 4) the primary efficacy endpoint and whether or not it was met (in order that failed or negative studies might be identified); 5) the name of the self-rated functioning scale/subscale/items used; 6) self-rated functioning scale scores at baseline (ie, randomization to adjunctive therapy) and the mean change from baseline to the study endpoint (including error measurements, p-values versus placebo, and patient numbers); 7) the setting; and 8) the source of funding. Published data were supplemented with data from ClinicalTrials.gov and study protocols/reports, where available. One reviewer extracted the data from included studies (CPW) and a second reviewer checked the extracted data (CE). Disagreements were resolved by checking the original data source. To assess the risk of bias in individual studies, one reviewer (CPW) judged the adequacy of randomization, blinding, and outcome reporting for each study.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 2,090 discrete records were identified and screened ().

Of the 293 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 26 articles were included, of which 20 reported one or more primary study, and six reported post hoc analyses of already identified studies. In total, these articles described 26 different studies, the characteristics of which are shown in . Five of the post hoc analyses were pooled analyses of aripiprazole, and are not discussed further.Citation23–Citation27 The sixth post hoc analysis reported self-rated functioning data from a risperidone study in more detail than in the primary manuscript.Citation28 No sources of bias were identified in individual studies.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

The only self-rated functioning scale used in the included studies was the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS),Citation49–Citation51 which was always a secondary or exploratory outcome. The SDS comprises three visual analog scales on which patients self-rate the extent to which symptoms have disrupted their: 1) work/studies (including paid and unpaid volunteer work and training); 2) social life or leisure activities; and 3) family life or home responsibilities. Each of these items is scored from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). Patients can skip the work/studies item if they have not worked/studied in the last week for reasons unrelated to their disorder (eg, retirement); the instructions are unclear for patients who have stopped working because of their depression. The majority of studies calculated the SDS total score, obtained by summing the scores for the three items (range 0 to 30).Citation37–Citation43,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48 If the work/studies item was unrated, as was the case for 10%–35% of patients (in studies where patient numbers by item were available), it was generally unclear whether these patients were excluded from the SDS total score, or whether the SDS total score was calculated by imputing the mean of the other two items in place of the work/studies item. One study calculated the SDS sum of items 2 and 3 score (range 0 to 20), since a large proportion of patients (25%–35%) had no work/studies rating.Citation33 Six studies calculated the SDS mean score, obtained by taking an average of the item scores for all items that were rated (range 0 to 10).Citation29–Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 Finally, four studies did not specify how SDS scores were calculated.Citation36,Citation44,Citation47

As can be seen in , 13 different adjunctive agents were used across the studies, of which five were second-generation antipsychotics. All were short-term studies (6–12 weeks), except for one 52-week study. The minimum number of ADTs (historical plus prospective) to which patients were required to show inadequate response prior to randomization ranged from one to two. Definitions of inadequate response varied, from “investigator judgment”, to strict definitions with qualifying scores on multiple rating scales at multiple time points.

Efficacy

Each of the second-generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, olanzapine as OFC [pooled data], and risperidone) had at least one dose that met the primary efficacy endpoint of their respective studies (improvement of depressive symptoms, measured by either Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score or 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale total score; ).Citation29–Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37,Citation47,Citation48 The combination of buprenorphine and samidorphan also met its primary efficacy endpoint at one dose.Citation36 All other agents failed to meet the primary efficacy endpoint of their respective studies, and were therefore failed or negative studies.

A summary of the SDS results from the included studies is given in . Baseline SDS scores were similar between treatment groups in each study. All groups (active and control) improved numerically from baseline to endpoint, as measured by the SDS total or SDS mean. Most active treatments showed a numerically greater improvement than placebo (except for dexmecamylamine, which had inconsistent results). However, the majority of agents, and studies, failed to show a statistically significant benefit versus placebo on the SDS total or SDS mean. Only four agents demonstrated efficacy (p<0.05 versus placebo) on the SDS total or SDS mean in at least one study: aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, edivoxetine, and risperidone. A large variation in placebo response was seen between studies.

Table 2 Change from baseline to endpoint in self-rated functioning scale scores (for the population who received ≥1 dose of randomized treatment and had ≥1 post-baseline efficacy evaluation)

Considering the individual SDS items, only one agent (aripiprazole) in one study had a statistically significant benefit on the SDS work/studies item. The study in question (Kamijima et al)Citation32 investigated two doses (3 mg and 3–15 mg) of adjunctive aripiprazole in a 6-week randomized treatment phase, and both doses showed a benefit on the work/studies item. Three other studies of aripiprazole were included in the review; none of these showed efficacy on the SDS work/studies item, despite having almost identical designs to Kamijima et al.

On the SDS social life item, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, edivoxetine, olanzapine (as OFC), and risperidone showed a benefit over placebo (p<0.05) in at least one study. On the SDS family life item, a benefit (p<0.05) was observed for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, olanzapine (as OFC), and risperidone in at least one study.

Discussion

This review of 26 randomized placebo-controlled studies showed that, of the 13 adjunctive agents identified, only aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, edivoxetine, and risperidone statistically significantly improved functioning versus placebo, as measured by the SDS total or mean, in patients with MDD and inadequate response to at least one ADT. In a previous meta-analysis of adjunctive second-generation antipsychotics in MDD, which was conducted prior to the availability of brexpiprazole data, only aripiprazole and risperidone were found to provide a benefit based on a composite endpoint of patient-reported functioning and quality of life.Citation52 Furthermore, a systematic review in patients with MDD who received ADT (but no adjunctive pharmacotherapy) found that many patients, particularly partial responders, continued to experience functional impairments after treatment, highlighting an unmet need in MDD.Citation20

Other than edivoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, the only agents to show statistically significant benefits on any SDS items in the present review were second-generation antipsychotics. Of these agents, aripiprazole and brexpiprazole have an indication for the adjunctive treatment of MDD, and OFC has an indication for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression (all in the US).Citation22,Citation53,Citation54 The development of edivoxetine as an adjunctive treatment for MDD was halted in 2013 because it failed to meet the primary endpoint in three Phase 3 studies.Citation55 Indeed, more than half of the adjunctive agents identified in this review failed to meet the primary efficacy endpoint of their respective studies. Nonetheless, the findings of this review suggest that the SDS as a whole is a useful scale to track changes in functioning among patients with inadequate response to ADTs, and that adjunctive second-generation antipsychotics or edivoxetine may improve functioning in such patients.

The SDS was the only self-rated measure of functional impairment that was used in the retrieved records. This observation is in line with a meta-analysis of second-generation antipsychotics for the adjunctive treatment of MDD.Citation52 Indeed, the SDS appears to be the most widely used functioning measure in studies of MDD.Citation20 The SDS is considered to be a reliable and valid measure of functioning impairment, originally developed in 1981 for use in treatment outcome studies in psychiatry.Citation49–Citation51 To the authors’ knowledge, no minimal clinically important difference has been established for the SDS. Sheehan selected the three items of work/studies, social life, and family life after reviewing other impairment instruments and consulting with patients and colleagues.Citation51 In general, all three items, including the work/studies item, are sensitive to treatment effects across a variety of psychological disorders.Citation51 In the present review, however, in the population of patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADTs, only aripiprazole had a statistically significant benefit on the SDS work/studies item, and this was only in one study out of four. Thus, where a benefit was observed on the SDS total or mean, this was generally driven by improvement on the social life and family life items.

There are several possible reasons for a lack of effect on the work/studies item in this population. Since the work/studies item is not rated for patients who are not working, one possibility is that the studies were underpowered to measure this item. In general, as shown in a US nationwide survey of patients with MDD, inadequate responders to ADT (based on self-reports) are less likely to be employed than responders.Citation14 Unfortunately, the majority of studies in the present review did not separate out the number of patients who rated each item of the SDS. Where such data were available, 10%–35% of patients across the studies with a rating on the social life and family life items did not rate the work/studies item. Thus, the power to show a difference between treatment groups was reduced for the work/studies item compared with the other items.

Nevertheless, 65%–90% of patients did rate the work/studies item, and therefore were in employment or studying. In general, studies have shown that people with depression who are in employment are less severely ill than those who are unemployed.Citation56,Citation57 Thus, on average, the subset of patients who rated the work/studies item may be less severely ill than the total population in each study. Meta-analyses have investigated the question of whether or not antidepressant efficacy increases with baseline illness severity, with varying results.Citation58,Citation59 If, as some have suggested, antidepressants are more efficacious in more severely ill patients, then the drug–placebo difference may be expected to be greater in the total population (ie, on the social life and family life items) than in the subset of patients in employment (ie, on the work/studies item).

Finally, it is possible that the studies were too short to show a benefit on the work/studies item. With a few exceptions, the included studies assessed functioning after 6 or 8 weeks of adjunctive treatment. In general, job performance deficits can still remain after 18 months among patients whose depressive symptoms have improved,Citation60 and patients with inadequate response to ADT are particularly at risk of persisting impairment.Citation61 Thus, acute studies may not be able to detect a benefit in occupational functioning in this population of inadequate responders. Only one of the included studies was a long-term study, and, over 52 weeks, adjunctive dexmecamylamine did not show a notable difference to adjunctive placebo on the SDS total.Citation41 However, dexmecamylamine failed as an adjunctive agent in MDD, having shown no differences to placebo on the primary efficacy outcome in four acute studies,Citation39,Citation40 and thus no benefit on the SDS might be expected.

Recent literature has acknowledged the difficulty in using the work/studies item among populations with a high proportion of non-workers, and attempts have been made to modify the SDS accordingly. Sonne et al proposed a rewording of the first item from “work/studies” to “work/daily tasks”, so that patients without a job could still rate the item.Citation62 Similarly, Bech reported a modified version of the SDS in which the work/studies item was replaced by an overall rating, “Your daily activities all things considered”.Citation63

The present review is limited because it only considered published literature, leading to a risk of publication bias (as positive studies are more likely to be published than failed or negative studies). However, even with the risk of publication bias, fewer than a third of the included studies reported a treatment benefit on the SDS. In addition, the review is limited since MEDLINE (via PubMed) was the only database searched. Nonetheless, the 26 studies identified had a consistent message, that the work/studies item is less informative in this population than the other two items.

Conclusion

The SDS, a self-rated functional measure, is informative in acute randomized placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive therapy in patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT. However, the item that measures work performance may be less relevant to this population than the items that measure social and family life.

Author contributions

CPW and CE performed data collection and analysis. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This review was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. (Princeton, NJ, USA) and H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark). Dr Jenny AR Muiry of Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd (Cambridge, UK) assisted with data collection. Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd also provided editorial support.

Disclosure

EW and HE are employees of H. Lundbeck A/S. CW and MH are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. CPW and CE are employees of Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd, which received funding from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S for this work. MF has received research support from, and has been a consultant or advisory board member for, all major pharmaceutical companies with drugs used in MDD. He owns the copyright for the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ) and a number of other psychiatric rating scales. Full lifetime disclosures can be viewed online at: http://mghcme.org/faculty/faculty-detail/maurizio_fava. He received no remuneration for his involvement in this review. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- KesslerRCThe costs of depressionPsychiatr Clin North Am201235111422370487

- DrussBGHwangIPetukhovaMSampsonNAWangPSKesslerRCImpairment in role functioning in mental and chronic medical disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationMol Psychiatry200914772873718283278

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceThe NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). NICE2010 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/evidence/full-guidance-243833293Accessed November 16, 2017

- NierenbergAADeCeccoLMDefinitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200162Suppl 1659

- AngstJKupferDJRosenbaumJFRecovery from depression: risk or reality?Acta Psychiatr Scand19969364134198831856

- FavaGABechPThe concept of euthymiaPsychother Psychosom20168511526610048

- ZimmermanMMcGlincheyJBPosternakMAFriedmanMAttiullahNBoerescuDHow should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspectiveAm J Psychiatry2006163114815016390903

- EvansVCLamRWAssessments of functional improvement: self-versus clinician-ratingsMedicographia2014364512520

- SaltielPFSilversheinDIMajor depressive disorder: mechanism-based prescribing for personalized medicineNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20151187588825848287

- McKnightPEKashdanTBThe importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment researchClin Psychol Rev200929324325919269076

- RushAJTrivediMHWisniewskiSRAcute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D reportAm J Psychiatry2006163111905191717074942

- MauskopfJASimonGEKalsekarANimschCDunayevichECameronANonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorderDepress Anxiety2009261839718833573

- KnothRLBolgeSCKimETranQVEffect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depressionAm J Manag Care2010168e188e19620690785

- American Psychiatric AssociationPractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder3rd edAmerican Psychiatric Association2010 Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdfAccessed November 16, 2017

- KennedySHLamRWMcIntyreRSCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatmentsCan J Psychiatry201661954056027486148

- FavaMPharmacological approaches to the treatment of residual symptomsJ Psychopharmacol2006203 Suppl293416644769

- FavaMRushAJCurrent status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practicePsychother Psychosom200675313915316636629

- ConnollyKRThaseMEIf at first you don’t succeed: a review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategiesDrugs2011711436421175239

- SheehanDVNakagomeKAsamiYPappadopulosEABoucherMRestoring function in major depressive disorder: a systematic reviewJ Affect Disord201721529931328364701

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationPLoS Med200967e100010019621070

- Symbyax® (olanzapine and fluoxetine) capsules for oral use [prescribing information]Indianapolis, INLilly USA, LLC2017

- ThaseMETrivediMHNelsonJCExamining the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of 2 studiesPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry200810644044719287552

- TrivediMHCorey-LislePKGuoZLennoxRDPikalovAKimERemission, response without remission, and nonresponse in major depressive disorder: impact on functioningInt Clin Psychopharmacol200924313313819318972

- SteffensDCNelsonJCEudiconeJMEfficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder in older patients: a pooled subpopulation analysisInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201126656457220827794

- FabianTJCainZJAmmermanDImprovement in functional outcomes with adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo in major depressive disorder: a pooled post hoc analysis of 3 short-term studiesPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2012146

- NelsonJCRahmanZLaubmeierKKEfficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole in patients with major depressive disorder whose symptoms worsened with antidepressant monotherapyCNS Spectr201419652853424642260

- PandinaGJRevickiDAKleinmanLPatient-rated troubling symptoms of depression instrument results correlate with traditional clinician-and patient-rated measures: a secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Affect Disord20091181–313914619321206

- BermanRMMarcusRNSwaninkRMcQuadeRDCarsonWHCorey-LislePKKhanAThe efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry200768684385317592907

- MarcusRNMcQuadeRDCarsonWHThe efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200828215616518344725

- BermanRMFavaMThaseMEAripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressantsCNS Spectr200914419720619407731

- KamijimaKHiguchiTIshigookaJAripiprazole augmentation to antidepressant therapy in Japanese patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (ADMIRE study)J Affect Disord2013151389990524074484

- QuirozJATamburriPDeptulaDEfficacy and safety of basimglurant as adjunctive therapy for major depression: a randomized clinical trialJAMA Psychiatry201673767568427304433

- ThaseMEYouakimJMSkubanAEfficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a Phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressantsJ Clin Psychiatry20157691224123126301701

- ThaseMEYouakimJMSkubanAAdjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a Phase 3, randomized, double-blind studyJ Clin Psychiatry20157691232124026301771

- FavaMMemisogluAThaseMEOpioid modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan as adjunctive treatment for inadequate response to antidepressants: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trialAm J Psychiatry2016173549950826869247

- DurgamSEarleyWGuoHEfficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry201677337137827046309

- FavaMRameyTPickeringEKinrysGBoyerSAltstielLA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 study of the augmentation of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist in depression: is there a relationship to leptin levels?J Clin Psychopharmacol2015351515625422883

- VietaEThaseMENaberDEfficacy and tolerability of flexibly-dosed adjunct TC-5214 (dexmecamylamine) in patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to prior antidepressantEur Neuropsychopharmacol201424456457424507016

- MöllerHJDemyttenaereKOlaussonBTwo Phase III randomised double-blind studies of fixed-dose TC-5214 (dexmecamylamine) adjunct to ongoing antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to prior antidepressant therapyWorld J Biol Psychiatry201516748350125602163

- TummalaRDesaiDSzamosiJWilsonEHosfordDDunbarGErikssonHSafety and tolerability of dexmecamylamine (TC-5214) adjunct to ongoing antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to antidepressant therapy: results of a long-term studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol2015351778125514064

- BallSDellvaMAD’SouzaDNMarangellLBRussellJMGoldbergerCA double-blind, placebo-controlled study of edivoxetine as an adjunctive treatment for patients with major depressive disorder who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatmentJ Affect Disord201416721522324995890

- BallSGFergusonMBMartinezJMEfficacy outcomes from 3 clinical trials of edivoxetine as adjunctive treatment for patients with major depressive disorder who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatmentJ Clin Psychiatry201677563564227035159

- BarbeeJGThompsonTRJamhourNJA double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine as an antidepressant augmentation agent in treatment-refractory unipolar depressionJ Clin Psychiatry201172101405141221367355

- SanacoraGJohnsonMRKhanAAdjunctive lanicemine (AZD6765) in patients with major depressive disorder and history of inadequate response to antidepressants: a randomized, placebo-controlled studyNeuropsychopharmacology201742484485327681442

- RichardsCMcIntyreRSWeislerRLisdexamfetamine dimesylate augmentation for adults with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to antidepressant monotherapy: results from 2 Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studiesJ Affect Disord201620615116027474961

- ThaseMECoryaSAOsuntokunOA randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, and fluoxetine in treatment-resistant major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200768222423617335320

- MahmoudRAPandinaGJTurkozIKosik-GonzalezCCanusoCMKujawaMJGharabawi-GaribaldiGMRisperidone for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2007147959360217975181

- SheehanDVThe Anxiety DiseaseNew YorkCharles Scribner & Sons1983

- SheehanDVHarnett-SheehanKRajBAThe measurement of disabilityInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 38995

- SheehanKHSheehanDVAssessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the Discan metric of the Sheehan Disability ScaleInt Clin Psychopharmacol2008232708318301121

- SpielmansGIBermanMILinardatosERosenlichtNZPerryATsaiACAdjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomesPLoS Med2013103e100140323554581

- Abilify® (aripiprazole) tablets; Abilify Discmelt® (aripiprazole) orally disintegrating tablets; Abilify® (aripiprazole) oral solution; Abilify® (aripiprazole) injection for intramuscular use only [prescribing information]Tokyo, JapanOtsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.2017

- Rexulti® (brexpiprazole) tablets, for oral use [prescribing information]Tokyo, JapanOtsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.2017

- Eli Lilly and CompanyLilly announces edivoxetine did not meet primary endpoint of Phase III clinical studies as add-on therapy for major depressive disorder [press release]Indianapolis, INEli Lilly and Company2013 Available from: https://investor.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=811751Accessed November 17, 2017

- BeckACrainALSolbergLIUnützerJGlasgowREMaciosekMVWhitebirdRSeverity of depression and magnitude of productivity lossAnn Fam Med20119430531121747101

- WilesNJMulliganJPetersTJSeverity of depression and response to antidepressants: GENPOD randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry2012200213013622194183

- KirschIDeaconBJHuedo-MedinaTBScoboriaAMooreTJJohnsonBTInitial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug AdministrationPLoS Med200852e4518303940

- FountoulakisKNVeronikiAASiamouliMMöllerHJNo role for initial severity on the efficacy of antidepressants: results of a multi-meta-analysisAnn Gen Psychiatry20131212623941527

- AdlerDAMcLaughlinTJRogersWHChangHLapitskyLLernerDJob performance deficits due to depressionAm J Psychiatry200616391569157616946182

- TrivediMHMorrisDWWisniewskiSRIncrease in work productivity of depressed individuals with improvement in depressive symptom severityAm J Psychiatry2013170663364123558394

- SonneCCarlssonJBechPElklitAMortensenELTreatment of trauma-affected refugees with venlafaxine versus sertraline combined with psychotherapy – a randomised studyBMC Psychiatry201616138327825327

- BechPMeasurement-Based Care in Mental DisordersCham, SwitzerlandSpringer International Publishing AG2016